Kilmarnock revival continues with Celtic shock

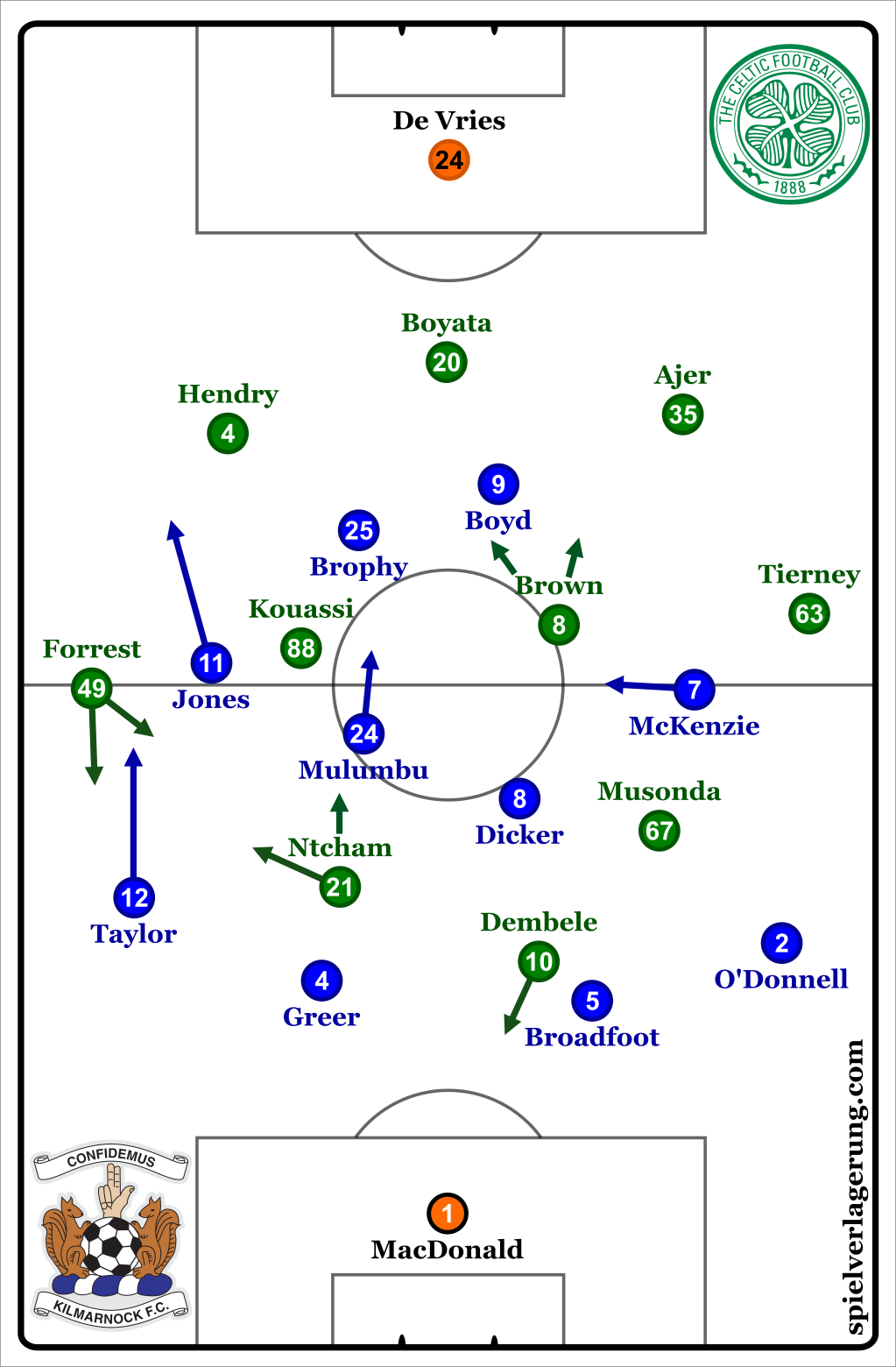

Kilmarnock inflicted Celtic’s second defeat in as many months at Rugby Park on Saturday. Having only taken over in October, Steve Clarke has already defeated both Rangers and Brendan Rodgers’ side at home, as well as securing respectable draws in Glasgow. Just as significant is the manner in which his team have achieved such success, showing a level of organisation rarely seen in Scotland.

Compactness and midfield pressing

Pivotal to these impressive results against the Old Firm has been Steve Clarke’s overhaul of Killie’s defensive organisation. Whether sitting back in their own half with a low block, or pushing up slightly to pressure the Celtic backline, the Ayrshire team showed a clear focus on access and midfield pressing.

In this respect, Kilmarnock are, perhaps, a unique side in the Scottish Premiership. While many teams have defended deep in their own half and tried to beat Celtic on the counter attack in the past eighteen months, almost all have done so through various degrees of man-marking – especially in the central midfield area. Brendan Rodgers’ Celtic side have become accustomed to playing against such systems, particularly the more extreme variants. In these matches, Celtic typically look to use their opponent’s defensive scheme against them, pulling markers away from key spaces, then attacking them quickly with their vast arsenal of attacking talent.

Steve Clarke’s side, as a result, are one of the only examples of well-executed position-oriented zonal defending to be found north of the border. They are uncharacteristically compact for a Scottish team, both horizontally and vertically. Such compactness deterred Celtic from playing into their creative central players, and gave Kilmarnock the access to apply intense pressure through several players from multiple angles if those passes were made.

Most of this impressive defensive organisation was seen in their deep 4-4-2. Dropping back into their own half, the front two of Kris Boyd and Eamonn Brophy together aimed to prevent Celtic from playing into either of their sixes, Scott Brown or Eboue Kouassi, either through the threat of their pressing, or by blocking passing lines.

Behind them, the midfield four of Jordan Jones, Youssouf Mulumbu, Gary Dicker, and Rory McKenzie ensured that Killie always had strong access to Celtic players in advanced positions. Shifting intensely in relation to the position of the ball, and keeping only manageable distances between them, they were able to drastically reduce the available time and space afforded to any Celtic player trying to receive the ball in the middle of the pitch. Indeed, the regaining of possession which led to the game’s only goal came from such a moment, as the short distances between McKenzie, Dicker, and Scott Sinclair allowed the Kilmarnock midfielders to double up on the Englishman from either side as soon as he received the ball.

Further back still, the defensive line contributed just as significantly to Kilmarnock’s intense compactness. Gordon Greer, in particular, was very aggressive in stepping out from the defensive line to press forwards. This, combined with the backwards pressure applied from the midfield, immediately closed any space their opponents might have hoped to exploit inside the defensive shape.

Furthermore, with so many players in the area surrounding the ball from all angles, Kilmarnock had a near monopoly on loose and second balls. Control of these chaotic moments, when both teams battle to establish possession, has been a hallmark of Steve Clarke’s side since he was appointed. Kilmarnock’s level of organisation in the phases which are typically the most unorganised is admirable, and given the frequency with which they occur, goes a long way to explain the revival they have had.

This level of organisation extends to their defensive structure in moments of last ditch defending. In moments when Celtic pushed Kilmarnock back into their own box, typically by advancing down the flanks, the home side were still had some control of a usually desperate situation. Many teams will defend such attacks by dropping midfielders into the defensive line, forming a compact ‘wall’ along the top of the penalty area. While the restricted spaces between players makes it difficult for their opponents to play through them, there is a significantly reduced capacity for pressure on the ball, as well as little contingency should that defensive line be broken. Kilmarnock, however, quickly arrange into two tight banks of four as soon as the ball is played back into the centre. With more ‘layers’ in their structure, not only do Kilmarnock have a stronger spatial coverage around the box for second balls, but pressure can be applied higher up, often taking away opportunities for shots from distance. Additionally, finding a penetrating pass in the first place is considerably more challenging for the opposition.

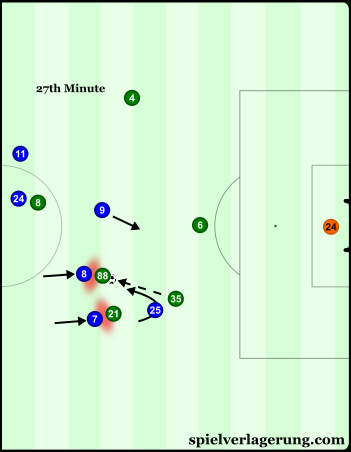

Kilmarnock’s midfield’s close proximity to the forward line allows them to maintain access to Celtic’s deep build-up. With Kouassi (88) receiving under pressure, he lays off to Ntcham (21), though the Frenchman is in a similarly precarious position. McKenzie presses from Ntcham’s blindside and wins the ball in a dangerous area.

Even in these moments of defending so close to their own goal, the forwards play an active role. Brophy, in particular, provided backwards pressure when his team were pinned back, further reducing the space Celtic had to build attacks.

Indeed, backwards pressure from the strikers forms another integral part of Kilmarnock’s defensive scheme. Killie adopted several pressing patterns throughout the game, some utilising the forwards’ back-pressing to great effect. Part of what made Kilmarnock’s defensive scheme so successful was their ability to restrict Celtic from circulating the ball around their back line completely freely. After forcing the visitors to the flank through their compactness and intense pressure in the centre, they would shut off forward and inside passing options, before Boyd or (more often) Brophy would curve round and join in the pressing. Isolating the Celtic wide player and pressing him from all angles with three or more players, Kilmarnock were able to win possession with relative ease.

The scale of the forwards’ involvement, though, was greater when pressing higher up the pitch. As with their deeper defending, Kilmarnock’s strikers would start by preventing passes into the Celtic sixes. On the occasions when they would press up on the opposing defensive line, they would do so keeping Brown and/or Kouassi in their cover shadow. In another simple yet rare move by a Scottish team, the forwards would be closely supported by their own midfielders, with Dicker and Mulumbu pushing up to maintain compactness and balance in their pressing. From this 4-4-2/4-2-2-2 structure, Killie could keep good access to the Celtic midfield line were they to receive a short pass, and utilise the numbers they committed forwards to pressing in any potential counter attacks.

Some other pressing patterns Kilmarnock displayed when defending high up had the potential to be very effective pressing traps. For most of the game, Jones worked extremely hard to press Jack Hendry on the right of the Celtic back 3, putting winger James Forrest in his cover shadow as he did so. This action was particularly evident after a switch of play from the Celtic left, as Jones would look to force the Celtic debutant back inside the pitch, preventing any ideas of Brendan Rodgers’ side creating favourable 1v1s on the right wing. On a number occasions, this pressure from Jones was effectively coupled with a similar, mirrored pressing movement from one of the forwards, approaching from the other side. This had the effect of channelling a Celtic defender straight into the super-compact Killie midfield, with counter attacks being supported by many players against an unorganised backline.

Jones stepping into the forward line to press Hendry was a common sight throughout the game, though it was when Boyd gained access to Bitton that their pressing trap was at its best. Boyd presses Bitton through the passing line to Brown, and into an area well controlled by Kilmarnock players.

One of the most impressive performers regarding pressing came in a most unlikely form. In a list of all the things Kris Boyd is associated with, his work against the ball would almost surely be near the bottom. Yet under Steve Clarke, the veteran striker has shown great aptitude when pressing, even though his mobility and stamina create a need for him to pace himself. While he may not be the quickest, Boyd picked his moments well, his timing in pressing was impressive, as was his anticipation and reading of which player to ‘jump’ onto. It may come as a surprise, but is certainly no coincidence, that the moments in which the ‘Hendry trap’ worked best were those in which Boyd gave himself access to either the ex-Dundee man, or Nir Bitton in the centre of the back 3.

Circulation and counterpressing

As well organised as Steve Clarke’s side were, Celtic’s game was far from perfect. In possession they were forced into long spells of U-shaped circulation by Kilmarnock’s compact defensive structure. A more detailed look at the pitfalls of such passing patterns – where the ball is moved from wing to wing across the back line, its path tracing a U on the pitch – can be found in this analysis of Celtic’s visit to Linfield. To summarise, though, ‘the U’ doesn’t pose the opposition any great threat, since it is very straightforward to stay compact whilst moving across the pitch. Gaps to play inside are, therefore, limited, which in turn makes it exceedingly difficult to penetrate in any way which helps creates good goal scoring chances.

In a way, Celtic’s circulation problems were both caused by and resulted in weak positional structures in possession. Kilmarnock’s compactness and midfield pressing took full advantage of the poor spacing and lack of connections particularly in the centre of the pitch. On the odd occasion when Celtic did manage to find one of the advanced players in their 3-4-2-1, there was seldom any support immediate enough to negotiate the aggressive Killie pressure.

A similar story was to be found on the flanks, where Celtic had notable trouble playing inside from the wings. This, at least in part, should be credited to another one of Kilmarnock’s pressing patterns. The ball-near winger and forward would block passes forwards and back respectively, while the near central midfielder and far striker would both prepare to ‘jump’ on the Celtic six looking to receive the ball inside – Kris Boyd again playing a starring role as the blindside pressing player. However, Forrest often found himself isolated in heavily unfavourable situations on the flank, with precious little structural support from his midfield teammates. From these positions, with so few passing options to reconnect to the middle of the pitch, maintaining possession is more than challenging.

Somewhat paradoxically, Celtic’s responses to losing possession so often through weak positional structures, involved further weakening them. Their creative players, particularly new signing Charly Musonda, started going outwith the Kilmarnock block to receive passes, unwittingly putting the super-aggressive midfield pressers in their blind-spot, and making them prime targets for extreme pressure. The central midfielders dropped into the defensive line too, creating a situational back 4 (or even 5 at times), with the intention of making the first line more resistant to pressing, but with the effect of reducing their options for forward passes and weakening their positional structure.

This compounded problems Celtic had earlier. With so many players now in the first line, James Forrest found himself even more isolated more often, with supporting players being sometimes as far away as the central ‘corridor’ while he confronted three opponents on his own.

Of course, this had wider ramifications for Celtic’s game. In the opening minutes Celtic were dominant. They launched wave after wave of attacks on the Kilmarnock box, constantly threatening to break through. Much of this was down to their counterpressing in the attacking third, with defenders stepping forwards aggressively to prevent opposing strikers from collecting clearances, and the sixes hunting down players trying to dribble out of pressure. As the U set in, however, Brown and Kouassi dropped deeper to be involved in circulation. From these deeper positions, they no longer had the same access as they did in the early stages to hem Killie in their own defensive third.

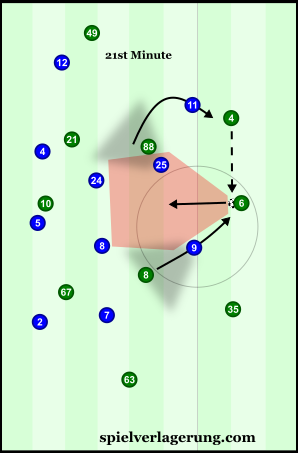

Build-up to the game-winning goal. Kilmarnock’s compactness allows them to double-up on the receiving player from both sides. His nearest teammates aren’t particularly accessible either, making it incredibly difficult for him to keep the ball. Brown’s dropping into the defensive line leaves the centre very poorly occupied, and allows Kilmarnock to advance into the Celtic half easily.

Run (diagonally), Forrest, run!

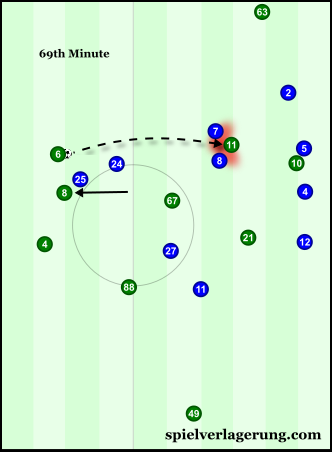

For all Celtic’s toils, they still managed a promising spell at the start of the second half. James Forrest was the prime catalyst, with driving, diagonal runs threatening to unlock Steve Clarke’s previously impermeable defence. After the break, Celtic seemed to favour their left side slightly – perhaps due to the proximity of Scott Sinclair, Kieran Tierney, and Musonda. Due to Kilmarnock’s ball-orientation, this shifted their block to that flank in response, leaving Forrest free on the right. Scott Brown would also seek to drag Eamonn Brophy more towards the opposite flank, taking him away from Forrest. Since Boyd, by this point, would not press readily on the touchline, Celtic could remove the backwards pressing that had restricted their wing play up to that point.

Furthermore, Celtic were starting to force Kilmarnock’s compact structure apart. Threatening depth much more than in the first half forced the defensive line back earlier. As the forwards tired, the distances between them and the midfielders grew larger. The absolute difference may only have been a handful of metres, and yet with those slight openings Celtic were able to attack with purpose. The wings were once again connected, Ntcham could position himself comfortably in the right halfspace to pin left-back Greg Taylor, both giving Forrest all that he needed to dive diagonally inside, playing between the lines and establishing position deep in the Kilmarnock half.

Naturally, Steve Clarke immediately addressed this alarming breach of his defensive system. Replacing Boyd with on-loan Aston Villa midfielder Aaron Tshibola allowed the Kilmarnock manager to address the compactness issues in both the forward and midfield lines. Kris Boyd was unlikely to last a full 90 minutes in such an intensely shifting defensive system – even if he already had a reduced workload – while bringing on an extra midfielder and switching to 4-1-4-1/4-3-2-1 afforded more protection of the areas Forrest was dribbling into.

The change of shape had other benefits too. From a 4-3-2-1, with Mulumbu and Tshibola ahead of McKenzie, Dicker, and Jones, Kilmarnock could defend with more ‘layers’ than in their 4-4-2, allowing the defensive line to drop deeper without losing too much in the way of vertical compactness. However, in order to prevent Brophy from being overloaded too easily in the first line, Mulumbu would move up and join him whenever Scott Brown dropped into the defensive line. Since this move from the Celtic captain took a player away from the Kilmarnock block, the Congolese midfielder could do this without a great deal of risk. From this situational 4-4-2, Killie could still maintain decent access to Celtic’s first line, but also cover more space more efficiently in the centre if the ball were to go into midfield – providing Mulumbu could get back in time.

And it is with this caveat that Celtic’s U circulation comes into focus again. With so many players so close to each other in the first line, Brendan Rodgers’ side’s circulation was particularly slow – giving Kilmarnock the time they needed to regain position after a switch. Indeed, one of Celtic’s best moments in the closing minutes came when the backline was comparatively undermanned, with Bitton staying upfield after a deep free-kick. With fewer players to pass the ball through, a direct pass from the centre diagonally to the flank found Kieran Tierney who immediately redirected it back into the centre for an onrushing Odsonne Edouard.

Conclusion

Kilmarnock under Steve Clarke are different from just about every other Scottish team. Where most teams see chaos, they see control. Their defensive scheme frustrated the champions, and restricted them to a measly 0.63xG according to @GoalCharts. Celtic will need to examine how they were able to fall so readily into their U circulation, and address their defensive transitions before Zenit St Petersburg come to town next week.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen