Celtic win comfortably over Linfield despite glaring possession problems

Linfield hosted Celtic at Windsor Park for the first leg of their Champions League second round qualifier, in a game that will be remembered more for events off the pitch than on it. With the match moved to Friday evening as opposed to the originally scheduled Wednesday night to avoid the Glasgow side’s playing in Belfast coinciding with the ‘Twelfth’, an already unusual scenario was only compounded by Celtic’s uncharacteristically poor play in possession, albeit in part down to the home side’s good defensive organisation.

Linfield’s solid defensive structure

The Northern Irish side were able to limit Celtic’s formidable attacking prowess through their defensive structure. Setting up in a low block with a 4-3-2-1 (wingers in line with the deepest midfielder and 8s higher), Linfield favoured very strong levels of vertical compactness instead of pressing Celtic’s deepest players in possession – in this respect it is perhaps more accurate to call their system a 4-3-2-1-0. Though it will be explored more in depth later, it was puzzling to see Celtic in some scenes build up with 6 (six) players against Linfield’s none in the first line.

When Celtic played to their central midfielders in one of the halfspaces (particularly Armstrong on the left), Linfield’s ball-near 8 would step out slightly next to the centre forward. This closed down any space the receiving player had to perhaps dribble into the midfield, as well as serving to increase the size of the area restricted through his cover shadow behind him. Meanwhile, the 6 would sit deeper and further protect the space immediately in front of the back four, tilting to whichever side seemed in most need in any particular moment.

Linfield’s coverage in wide areas caused the away side problems. Both wingers were somewhat withdrawn, giving them good access to Celtic’s advanced fullbacks. Additionally, they were prepared to be the first player to press on the flank, allowing their own fullback to cover whilst maintaining access to his position in the back four. Celtic have had considerable joy domestically manipulating fullbacks to pull them away from or out of the defensive line, before attacking that area through midfield runners or advancing fullbacks, but with Linfield’s back four very horizontally compact, there was little space for runs or passes to be made through them.

This control of the flanks came with the risk of leaving the centre unprotected. It was not uncommon to see the wingers fall into the defensive line, creating situational 6-3-1 structures. This could have proven costly, as it did to Aberdeen in the Scottish Cup final, with players of Celtic’s quality afforded space in the centre of the pitch. This, however, was not the case.

Celtic’s U-shaped circulation

Despite hoarding the ball for vast periods of the game, Celtic ultimately struggled to create decent chances in open play. They had very few options to play inside the Linfield block due to their positional structure. This resulted in what is rather descriptively called “The U”, or “horseshoe circulation”, named after the shape the ball traces across the field as it is switched up, back, and around the defensive line. The U is a dreaded consequence of poor positioning, namely because it allows the defending team to simply shift from side to side, without the threat of exposing passing lanes to players between the lines in the centre. If there is at least some sort of threat in this area, opposing midfielders have a much more difficult task, as they must now shift towards the ball-side whilst also referring positionally to a (mostly likely) moving player behind them in their blind spot. Any inaccuracy in their perception or movement could lead to an attacking player receiving the ball in one of the most dangerous areas of the pitch.

Rogic, as the 10, should have been the main player occupying this space inside Linfield’s defensive shape. However, through both the opposition’s very strong compactness, access to & aggressive pressing of players between the lines, and the Australian’s tendency to drift over to the right halfspace (oftentimes even outside the block altogether), Celtic struggled to establish decent position or possession in this space.

There are possible reasons why Celtic would reject occupation of the centre in favour of The U. One of the main characteristics of such circulation is that it provides very little risk for the team in possession. With no initiative to play passes between opponents and into tight areas, there is little chance of losing the ball. Even if possession is lost, it is likely lost on the flanks, which offers fewer options for counter attacks. Furthermore, since there are so many players outside the defensive block, in the transition moment there are, by the same token, many players already behind the ball.

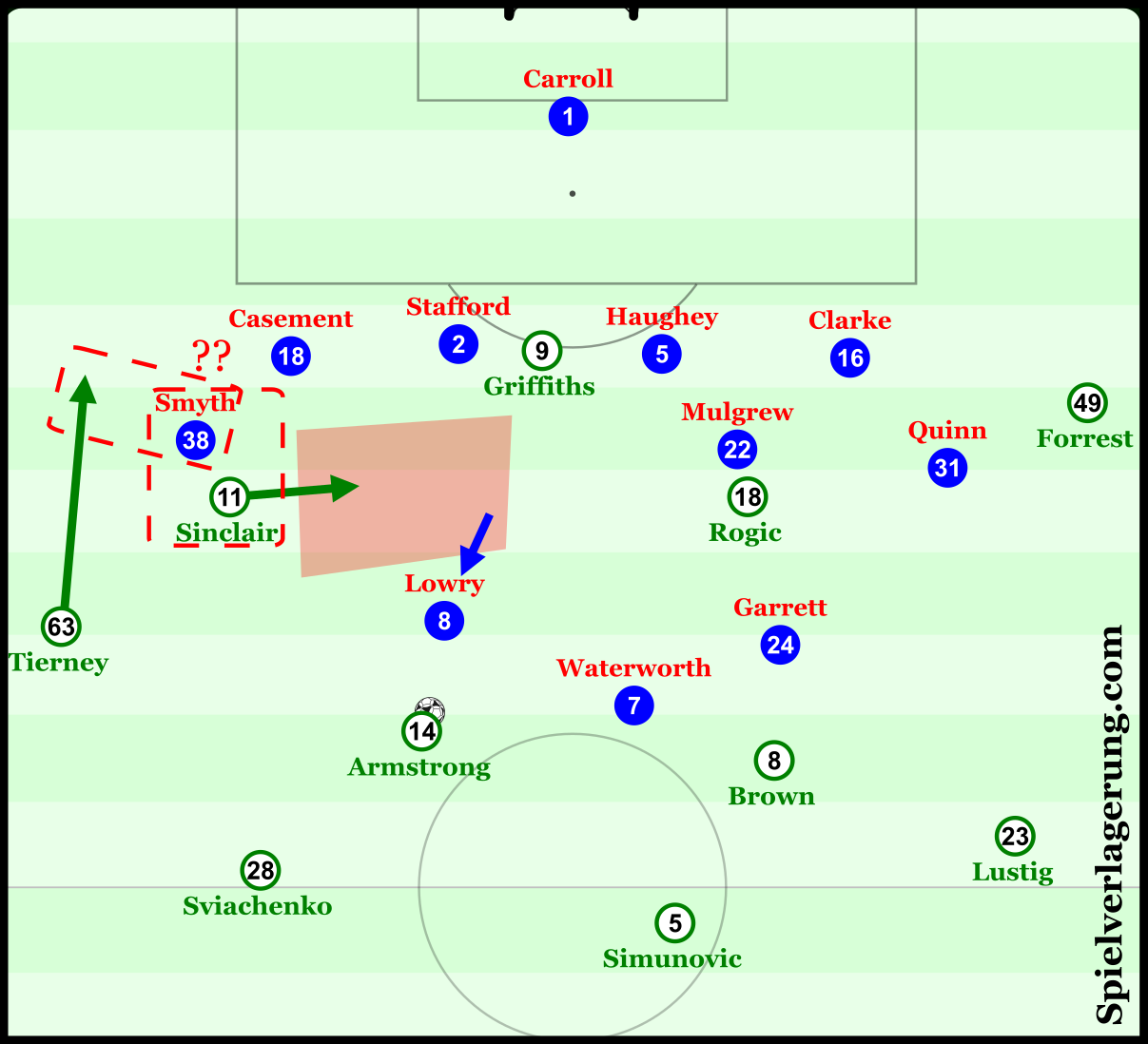

As Armstrong dribbles into the centre of the Linfield midfield, his ‘gravity’ increases greatly, as the opposition try to ensure he has no space to break through directly. This, however, opens up plenty of space for Sinclair to attack the goal diagonally however he pleases. In this instance he slips in the underlapping Tierney.

It is unlikely, however, that this was Celtic’s intention. Simply put, Linfield didn’t show anything particularly exciting in their handful of counter attacks. Celtic’s defence and central midfield should have been (and were) more than comfortable in dealing with the transition. Even though Linfield initially gave up a lot of space by immediately retreating into a low block, Celtic managed to force them back even further through their circulation. By pinning Linfield back so much, and forcing them to shift side to side so often, the player who won the ball rarely had any support or connections to move the ball away, making them easy targets for counterpressing. Combined with their spacing (players connected in possession are also connected out of possession) Celtic effectively settled their work in defensive transition before they even lost the ball. This is a good example of using the ball as a defensive tool, or Tikinaccio.

It is also possible that Celtic wished to use flank-oriented circulation to use their wingers’ 1v1 abilities on isolated fullbacks. By playing a few passes on one flank, drawing the opposition over to that side, then switching quickly, it can be possible to create these isolations. While this is a tactic which the Hoops have employed domestically, in Belfast it came up short. This is partly down to the aforementioned defensive coverage of the Linfield wingers, maintaining access to and doubling up on Sinclair/Forrest. Additionally, passing around the back is actually a poor means to generate this type of situation. With no reason to maintain coverage to central teammates, the Linfield wide players were free to stay within pressing distance of the Celtic wingers, harassing them as soon as they got the ball. The odd occasions when Celtic played centrally first, and then looked to the wings were much more beneficial. Passes into the centre of a defensive block tend to cause the opposition to ‘squeeze’ their positional structure towards the ball, for fear of leaving spaces large enough to immediately play a penetrating pass. Of course, this then leaves the flanks considerably more free, allowing for wingers or fullbacks to get in behind the defensive line.

Possible solutions

In Celtic’s most recent friendly against Shamrock Rovers, we saw similar positioning from Rogic as in Belfast. In that game, he was outstanding – standing in the right halfspace, able to receive flat, direct, diagonal passes from the defensive line with good body position, allowing him to turn and attack the defensive line immediately. At Windsor Park, however, Linfield’s compact midfield – the jobs their 8s did in screening such passes in particular – prevented this type of play from being viable.

With good spacing and timing, Tierney’s run could pin Smyth at the same time as Sinclair moves to occupy the space opened by Rogic. From here, a deeper Armstrong (himself drawing out Lowry) could either find Sinclair directly in this space, or indirectly with a layoff from a teammate.

Against Shamrock, Rogic’s movement was balanced by Sinclair. Last season’s player of the year would move into the left halfspace, with Kieran Tierney providing width on the left side, creating a very clear, situational 3-2-4-1 structure. Although Sinclair didn’t show the same level of pre-orientation as his Australian counterpart in that game, such a movement is very effective in creating a simple overload in midfield. If Sinclair left this space free and then moved into it at the right time, he could take advantage of Linfield’s 6 hedging towards the other side to retain access to Rogic, as well as the right 8’s pressure on a deeper Stuart Armstrong. With a typical Tierney run pinning the fullback and/or the retreated winger, Sinclair would have enough space to turn and attack the centre of the Linfield back line – either for himself or for runners in behind.

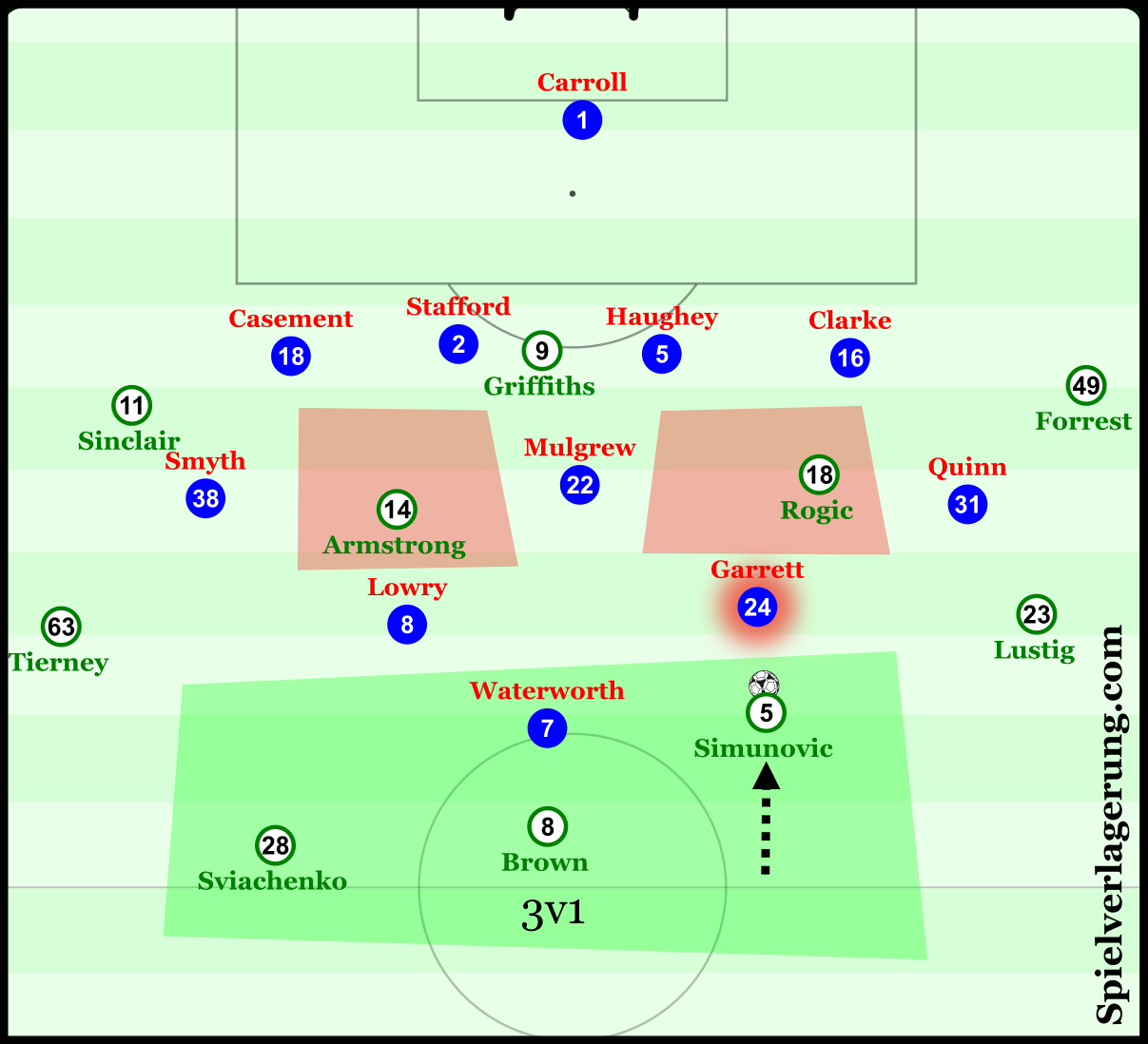

Alternatively, Armstrong could have occupied this space himself, as he has done in previous games (and, indeed, on a couple of occasions in this). Rotating the midfield ‘triangle’, even situationally, would have given Celtic a number of opportunities to create advantageous positions in the centre of the pitch. Firstly, it would’ve removed Linfield’s ‘natural’ access to Rogic, Brown, and Armstrong, given to them by their own midfield structure. Their 1-2 triangle in midfield matched Celtic’s 2-1, with the Celtic 10 able to be picked up by the Linfield 6 without greatly straying away from his position. With Linfield defending so positionally, it would have been interesting to see how they would deal with a deeper Scott Brown, and if they would have been able to defend against a double-8/10 at the same time.

With Armstrong and Rogic now either side of Mulgrew, Linfield have to either alter their positional structure, find ways to prevent the two Celtic men from exploiting their central space. Such a superiority in the first line allows Simunovic to dribble into midfield, either to pick out Armstrong and Rogic, or to even go in depth to any of the three players waiting.

With the extra space afforded to them by the advancement of Armstrong and the central tilting of Brown, we could have seen a lot more of Jozo Simunovic dribbling at the Linfield midfield. With decent enough spacing, this could have been used as a tactic to pull one of the midfielders out of position to press the Croatian, freeing up one of Celtic’s more advanced players for a moment.

Additionally, with two players looking to constantly position themselves between the lines, Linfield’s defensive shifting would have to be considerably more precise, to not only shut off passing lanes to Armstrong and Rogic, but to also be able to cover players who would look to fill those areas dynamically.

The last option is one that Celtic ended up doing often. Tierney and Lustig both do a good job in balancing their wingers’ positioning (generally one inside, one outside). This maintains spacing (for dribbling, for example), and gives options for the deeper player to run through, ready to be slipped in or used as a decoy. Considering Sinclair’s attraction for the touchline on Friday, the filling of the left halfspace was left to young Kieran Tierney. As much as the left-back has developed in the past couple of seasons, if he is the player who is getting into space most often in key areas of the pitch, with Scott Sinclair and Stuart Armstrong both in the vicinity, something has probably gone wrong with the positional structure.

Substitutions slightly change dynamic

Celtic made two changes with around twenty minutes remaining, bringing on Hayes and Dembele for Forrest and Griffiths. Hayes offered much the same as Forrest did, perhaps being slightly more dynamic in his taking on of the (probably exhausted) fullback, but also without great joy in his final delivery – albeit with his weaker right foot.

Dembele, however, offered a slight change in how Celtic’s play panned out. Griffiths primarily looks to seek depth in his runs, whereas on Friday there was very little space in behind the Linfield defence, due to their very deep line. The introduction of Dembele gave Celtic the opportunity to link up through their centre forward – an option not afforded to them by Griffiths.

Had Armstrong anticipated the play faster here he could have received the ball in a dangerous area with Sinclair and Dembele running in behind. The diagonal pass up and layoff allow for the blindside of nearby players to be taken advantage of. Even though Armstrong can’t read the play quickly enough to capitalise on the situation, Lowry doesn’t see him until he already has the ball.

The Frenchman’s layoffs have improved greatly in the past year, and came close to causing the home side considerable problems. By being able to quickly set the ball back to a forward-facing teammate, Dembele can essentially be used as a forward pivot, which has frightening connotations. Suddenly, there is the prospect of starting an attack on one side of the pitch and using Dembele for a diagonal layoff to a forward-facing player on the other. The receiving player can use the orientation of defending midfielders towards the side with the ball to make moves through their blindsides, making him far more troublesome to deal with.

Conclusion

For Celtic to have left Windsor Park on Friday night with anything other than a victory to take into the second leg after controlling the game so convincingly would have been absurd. Indeed, it is not so difficult to imagine that being the case. That both the away goals came from corners despite their dominance in open play is an indictment of Celtic’s inefficiencies with the ball in this match. A much better display is to be expected, if not perhaps required, on Wednesday.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen