Celtic overcome combative Aberdeen in Scottish Cup final

Celtic completed an unprecedented domestic treble on Saturday, as they defeated Aberdeen in the Scottish Cup final, adding to their League Cup and Premiership titles. Brendan Rodgers’ side went unbeaten in all competitions in Scotland in the Northern Irishman’s first season in charge. Though they managed to win the league at a canter, finishing a staggering thirty points ahead of second-placed Aberdeen, Celtic were forced into a gruelling contest by the Dons to round off their record-breaking season.

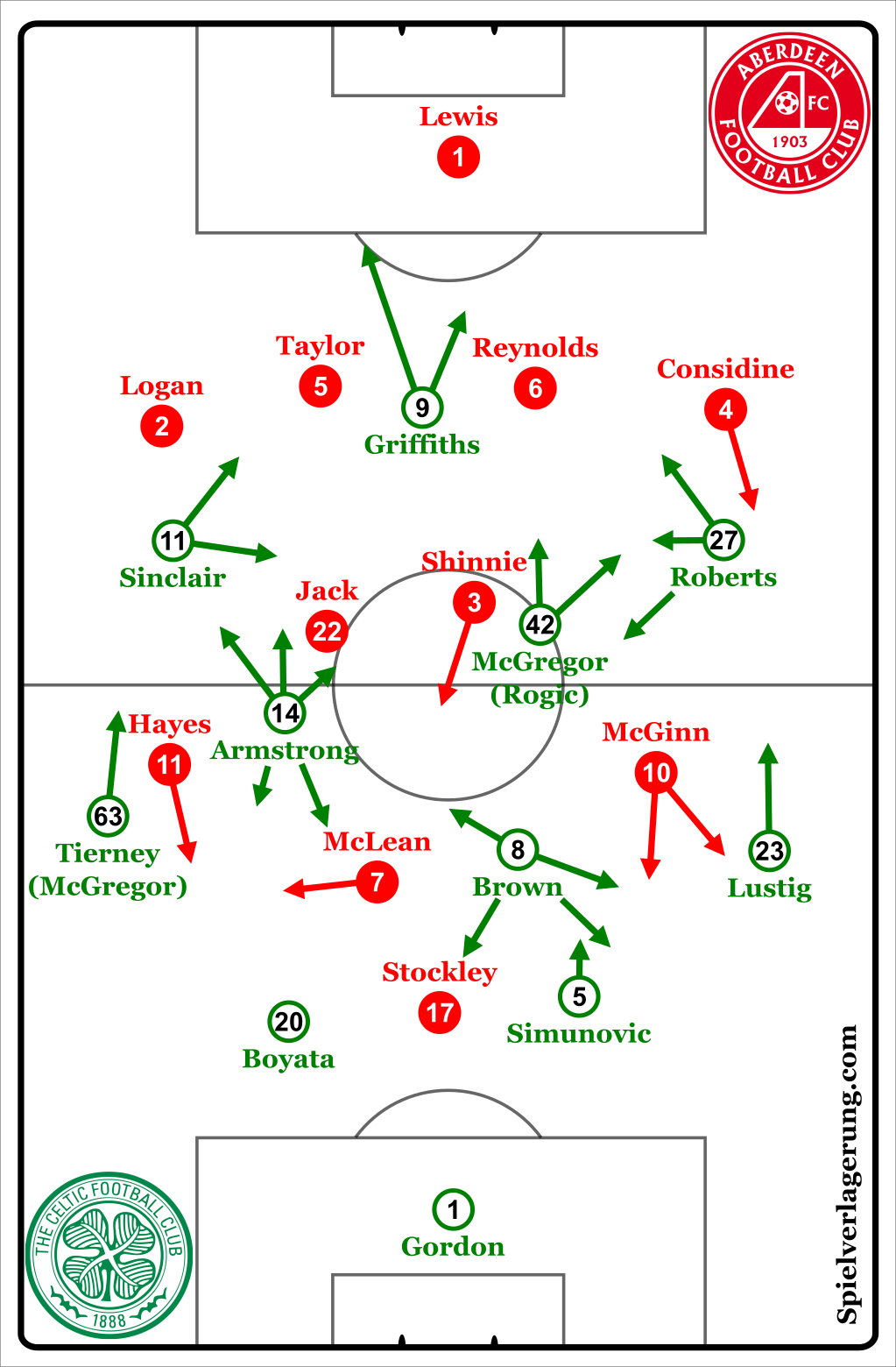

Line-ups

Aberdeen started the final with the notable exclusion of 20-goal striker Adam Rooney, with ex-Bournemouth man Jaydon Stockley preferred to the Irishman up front. Otherwise, Derek McInnes’ side lined up as expected, with a midfield trio of Ryan Jack, Graeme Shinnie, and Kenny McLean flanked by ex-Celtic Niall McGinn, and PFA Scottish Player of the Year nominee Jonny Hayes. Goalkeeper Joe Lewis was protected by their regular back four of Andy Considine, Mark Reynolds, Ash Taylor, and Shay Logan.

Celtic, had no such surprises. Moussa Dembele was deemed still not fit enough to make an appearance, so Leigh Griffiths led the line for the champions, joined by the ever-roaming Scott Sinclair and Patrick Roberts. While their nominal 4-2-3-1 placed Stuart Armstrong and Scott Brown in a double pivot behind Callum McGregor, often Brown, would remain the deepest of the three, allowing the other two central midfielders to make runs into depth and out wide. Dedryck Boyata partnered Jozo Simunovic in the centre of defence, with Mikael Lustig and young star Kieran Tierney the full-backs.

Celtic struggle to control the game

Perhaps surprisingly, given their domestic dominance, Celtic toiled for most of the game to gain control. Between the strongly man-oriented and direct approach employed by Aberdeen, and Celtic’s uncharacteristically poor reaction to it, it was only in the final stages of the game that the Hoops managed to assert their dominance on what had been arguably their toughest test in Scottish competition.

Aberdeen’s man-marking

Derek McInnes’ Aberdeen are perhaps the archetypal Scottish team. Very direct in possession, with quick wingers looking to supply a target-man striker, strong in set-pieces, and strict man-marking without the ball. Though it might not be the most attractive of strategies, it has led a previously floundering Aberdeen side from mid-table mediocrity to three consecutive second-placed finishes in the league and a League Cup.

There were no deviations from this approach from the Reds in their latest battle with Celtic. Despite losing all five of their previous encounters with the champions, McInnes drew positives from fragments of recent contests – namely the last 75 minutes in their last meeting at Pittodrie, where they managed to restrict Celtic, albeit after losing three goals in the first 15.

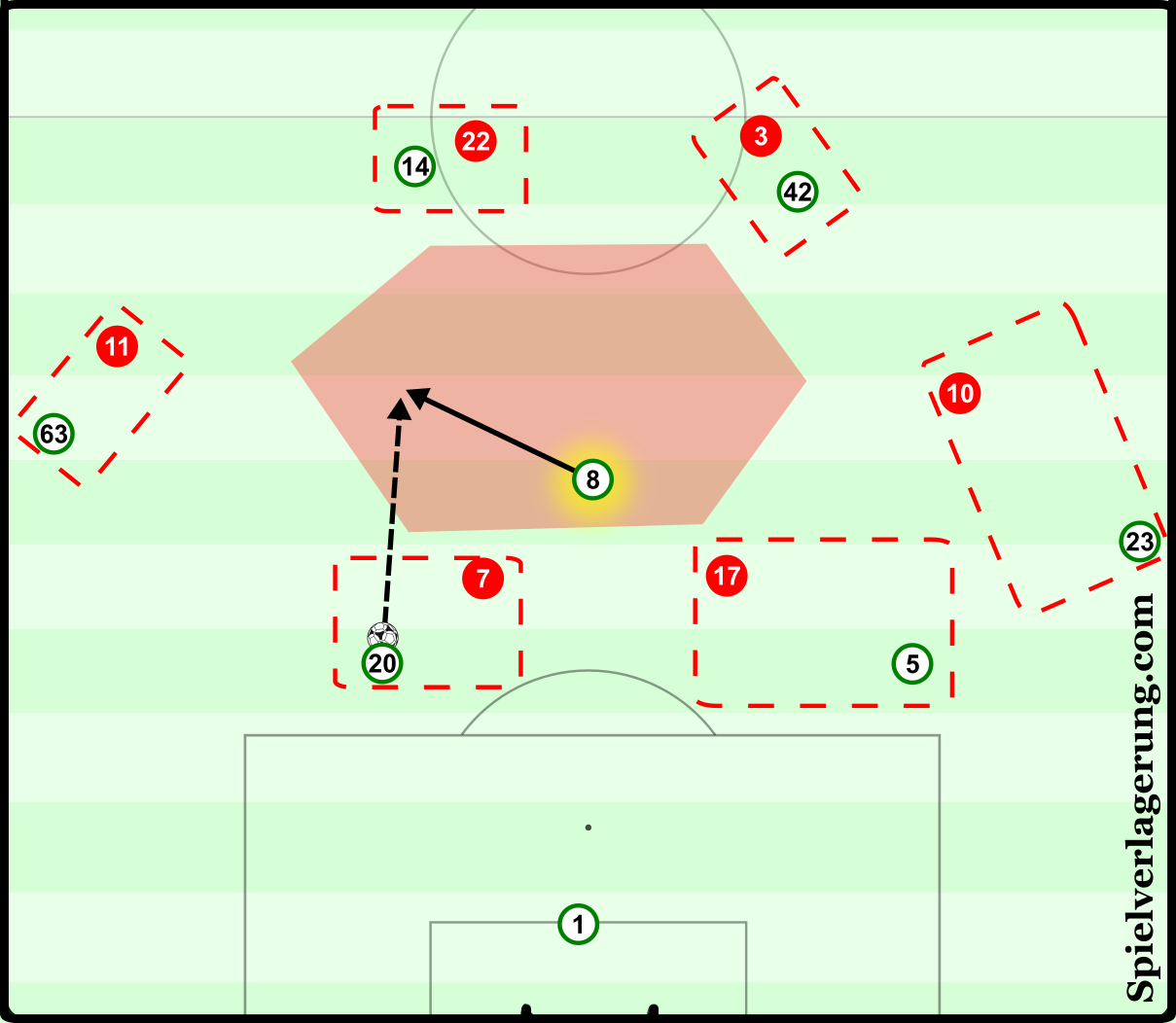

Aberdeen employed a man-marking defensive system, very strict by today’s standards. In most phases of Celtic possession, Aberdeen man-marked with every player, leaving only one centre-back free – some situations resulted in no free defenders at all.

Aberdeen’s initial pressing of the Celtic back line was easily broken, as Brown was left free by the spacing of his teammates to receive centrally. He is in such space that Boyata can pass into space to avoid the cover shadow of McLean.

The consequences of this type of approach are well documented. Positioning primarily with reference to the positioning of an opponent gives easy access to them for pressing, impedes the creation of a ‘free man’, and since each movement of an attacking player is to be matched by a defender, there is little opportunity for overloads of certain areas. This can be attractive for a team looking to ‘spoil’ the game of an opponent, particularly one that likes to build up play in a controlled manner, since the recipient of each pass should have a marker with the immediate access to place them under strong pressure. Ultimately this often results in the player in possession being reluctant to play a pass to such a player, and so the ball is played long instead.

In Aberdeen’s case, this occurred with Celtic’s goalkeeper, Craig Gordon. Though he is an excellent shot stopper, Gordon’s short possession game leaves a lot to be desired. As such, when Aberdeen man-marked every one of his teammates and left him as the free man, he wasn’t comfortable using this to his advantage to combine with his defenders to break the press. He resorted to long goal kicks and mid-distance balls to the fullbacks. Aberdeen’s centre-backs were more than happy challenging a striker smaller, but no less combative, than them in the air.

On occasions when Celtic did manage to get the ball in play with their centre-backs, Aberdeen retreated into a medium block – their first line of pressure engaging Celtic at around the halfway line. Hayes and McGinn would orientate themselves with respect to the fullbacks, initially loosely if they were still far from goal, in order to retain some level of access to their central teammates, then tighter as they advanced up the pitch. This loose man-orientation from the wingers when Celtic had deep possession also had a positive effect on Aberdeen’s counter-attacking play, as it would leave the winger unmarked in the event of a turnover. However, since Tierney, and then McGregor, naturally pushed higher up than Lustig, Hayes often found himself as an auxiliary right back, pinned into the defensive line by his man.

While this denied Celtic the opportunity to use the fullbacks as free men on the flanks to retain possession, it created a problem centrally, ultimately leading to Celtic’s first goal. With Hayes forced back into the defensive line by Tierney instead of in midfield, there was no cover for Ryan Jack when a loose ball evaded him and ended up at the feet of accomplished distance-shooter Armstrong, who had plenty of time to steer a left-footed shot into the bottom corner.

As Hayes is pinned back in the defensive line by the aggressive positioning of Tierney, a missed tackle by Jack leaves Armstrong completely free to score his 17th goal of the season.

Celtic’s fluid positional interchanges forced Aberdeen into a messy, but simple, defensive system. In the first instance, it appeared straightforward, with Aberdeen pressing in a rough 4-4-2, McLean and Stockley marking both Celtic’s centre-backs – restricting their ability to get on the ball and build. Due to Celtic’s midfield spacing, though, neither Jack nor Shinnie had the access to press Brown as he simply moved behind the first line of pressure to receive and turn.

Therein lies one of the biggest problems with man-marking. If one marker loses his man, or is dribbled past, the rest of the attacking team can, through their positioning, create situations where subsequent markers must choose between either continuing to mark their man and leaving the ball-carrier without pressure, or pressing the ball-carrier and leaving their man free. A well-coordinated team will be able to progress up the pitch with ease just by exploiting and ‘stacking’ this superiority over and over.

Aberdeen ‘solved’ the problem of Brown as the free man by withdrawing McLean to man-mark him, leaving Stockley 1v2 against the Celtic centre-backs. Jack and Shinnie continued to mark Armstrong and McGregor (later Rogic). In these orientations, the marker would be marking a player in his own zone, then follow him wherever he went until there was no more perceived threat from them.

Due to Celtic’s frequent interchange of positions – especially in advanced areas – Aberdeen players were drawn into unfamiliar territory. Fullbacks Logan and Considine would begin marking Sinclair and Roberts respectively out wide, but would not pass them on when they made their signature movements infield. It was not uncommon to see either fullback marking in the centre of midfield. Only when there was a break in play, or if there was no immediate danger, would they look to pass their man on to a more suitable player. Celtic managed to exploit this well, but not often, to get very favourable 1v1 situations – usually Sinclair or Roberts against one of the central defenders in a wide position.

Celtic initial slow response

Celtic have often used a fluid 4-2-3-1/3-2-4-1 in this, their record-breaking season. The differences in player-profile between Tierney and Lustig can lend itself to asymmetrical positioning, as the more forward-minded Tierney pushes up almost as a left midfielder, while Lustig tilts the other way and forms a de facto back three. With Roberts playing instead of Forrest, however, and given his effectiveness when playing near the ‘ten space’, Lustig stayed in his right-back position, making the odd foray into the Aberdeen half.

The back three was, nonetheless, created situationally. Brown and/or Armstrong would drop to one side of the centre backs, taking their marker with them and opening space in the centre for their technically gifted players to exploit.

This, however, required getting the ball to these players in advanced positions, and in situations where they could use these skills. With Aberdeen marking so rigourously, Celtic found it difficult to get anyone free high up the pitch. This was surprising given that this has been an area in which Brendan Rodgers’ side have been more than competent this season. Their dynamic occupation of the centre would have caused most teams problems, but since Aberdeen’s markers stayed with their men for so long, there was little impact from Armstrong & McGregor/Rogic’s movement wide and Sinclair & Roberts’ subsequent moves infield. Griffiths made depth-seeking runs in order to push the defensive line back, making the central space even bigger.

It was not just the wingers who could fill this central space once it had been vacated. The centre-backs, Simunovic in particular, would occasionally look to dribble into the centre. Ideally the ball-carrier looks to draw pressure before finding newly created free players. However, Celtic’s spacing often saw Simunovic crowded out, forcing him to play shorter passes to players who were marked – killing the rhythm of the attack. Boyata hardly looked comfortable taking on this responsibility, and on the rare occasion that he did, the timing and selection of his passing did very little to place Aberdeen’s markers in compromising situations.

The positioning of the players occupying central areas for Celtic didn’t help much either. There were very few instances of the Hoops using layoffs from direct passes to break the Aberdeen marking. Third man runs are an effective way of getting free, forward-facing players the ball, especially when the third man makes his run on the blind side of the defender. Such moves though require players to be in positions to make these runs. Celtic were often without the required spacing and staggering to do so. When they did have an adequate positional structure, Aberdeen’s man-marking forced the first direct pass to be near-perfect, at the risk of it being intercepted, launching a counter-attack.

Aberdeen’s attacking play

Typical of a Scottish team, most of Aberdeen’s chances came through set pieces, counter-attacks, and crosses. In organised possession, their play was limited, with none of the back four being particularly precise in their build-up play. McLean was used as a target-man, drifting over to the right side to match up against Boyata or Tierney, to great effect. Stockley’s presence up front gave the Dons another direct option. Much like Man Utd’s Europa League final victory against Ajax, Aberdeen avoided Celtic’s pressing by bypassing it at almost every opportunity.

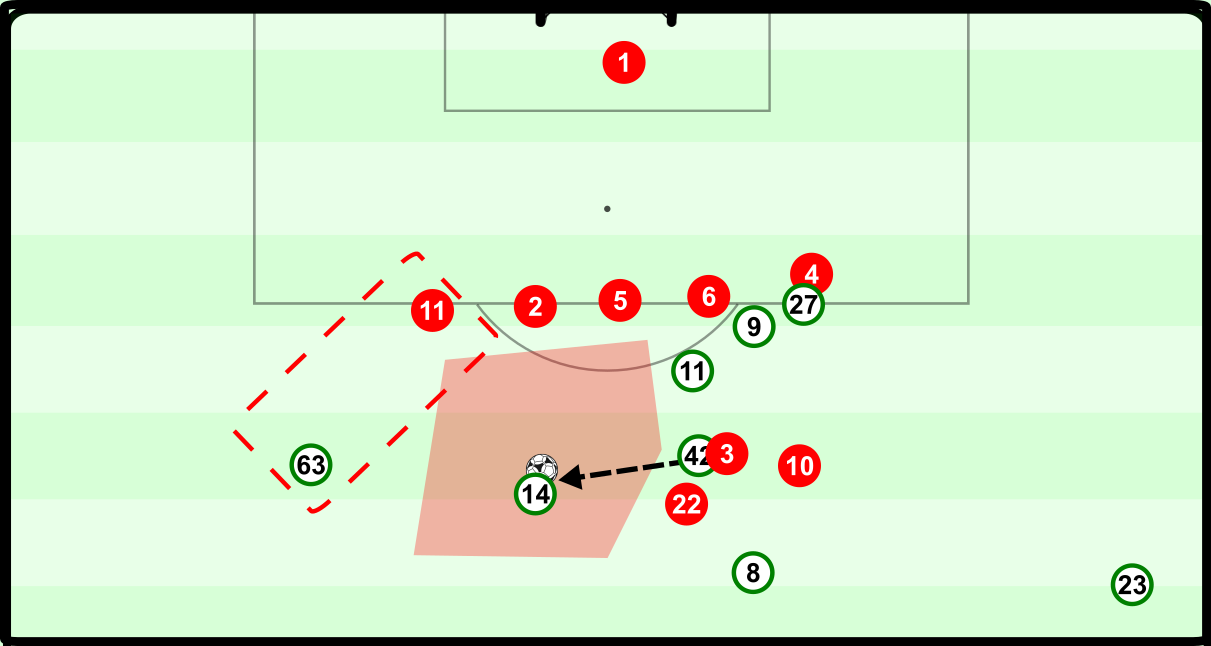

They did, however, have some joy breaking through the Celtic back line with relatively straightforward wing dynamics. On both flanks, they managed to couple the winger’s dropping movement towards the ball with a run in behind from the near-side central midfielder, who became available for a clipped pass in behind.

Once in possession on the wings, Aberdeen attacked the box well. The profligacy of a crossing-based attacking approach has been well documented, yet the way they occupied and supported the penalty area made the most of a bad situation. The Dons frequently got good numbers in the box, leading to roughly even and favourable match-ups. Considine would make runs towards the far post if needed, making the most of his good aerial ability. Outside the penalty area, Aberdeen made sure they had the area around the top of the box covered either by man-marking Celtic’s players in these areas, or by just marking them zonally. This had the dual purpose of preventing Celtic counters as well as helping Aberdeen regain possession after clearances, continuing their attacks.

McInnes’ defensive scheme had in impact on Aberdeen’s ability to create counter-attacking opportunities. By man-marking, he surrendered his team’s ability to be proactive in the types of opportunities they had in transition, instead relying on what their opponents afforded them through their positioning. This created a dichotomy of quality in Aberdeen’s counter-attacking. Since they had at least loose man-orientations when Celtic were building up in their own half, if they managed to turn over the ball in these phases, they would automatically have a generally favourable match-up numerically. This saw the Dons often counter attack with evenly-strength numbers, and led to their best chance, as Hayes dispossessed McGregor in the Celtic half, creating a 2v1, with McLean pushed up due to his orientation on the centre-back.

Final stages

The flip side of such an approach was seen in the final stages. Celtic pushed both fullbacks up the field, thus pinning the Aberdeen wingers in or near the defensive line. From here, they were wholly ineffective at contributing in counter-attacks. Celtic could isolate any counters with their counterpressing, crowding the ball-carrier out before he could find support.

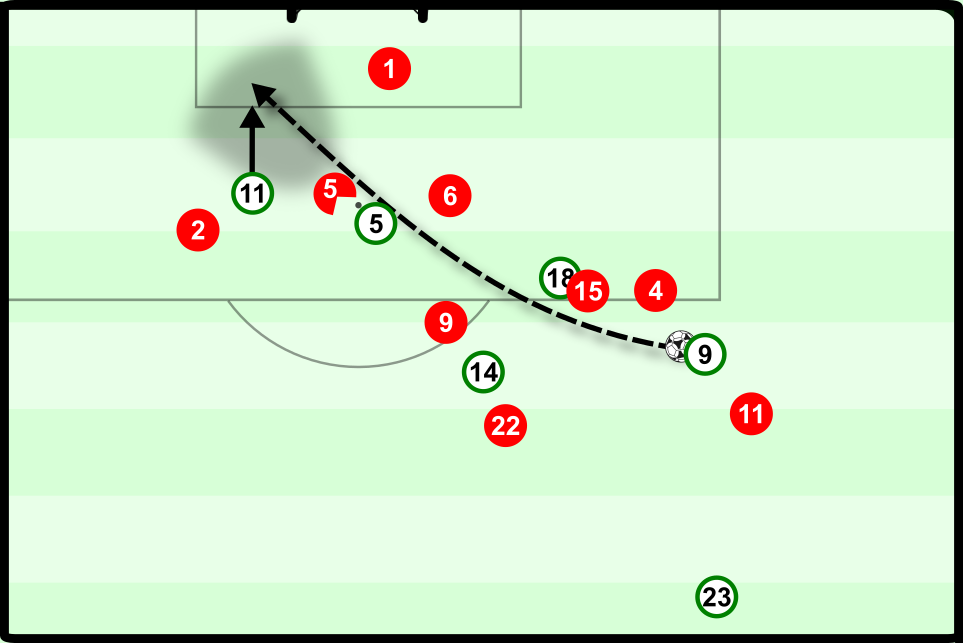

Griffiths’ in-swinging delivery forces Taylor to face up the pitch, leaving Sinclair to exploit the blind-side for a fantastic late chance.

While Griffiths seems to thrive when attacking depth against a high line, when playing against a team camped inside their own box, it is Sinclair who comes into his own. The ex-Chelsea forward made many of his trademark diagonal runs in behind the defence, particularly for left-footed deliveries from the right-side edge of the box. With such balls over and behind the defensive line, the curl on the ball’s path invites the far-side fullback to attack it with his back to his own goal – as opposed to an ‘out-swinging’ ball, which leads a fullback to initially turn to face it. Also, keeping it away from the goalkeeper, this type of pass allows Sinclair to exploit the blind-side of the far-side fullback, leading to a couple of great chances for the Englishman.

Conclusion

By the 75th minute, the physical toll of Aberdeen’s man-marking was showing. No longer were they able to sustain high pressure on the Celtic back line, forcing them into a deep block. From here, the champions were able to assert their dominance on the game. Pushing the full-backs high up the pitch freed up Roberts and Sinclair to play centrally. As Reds’ legs grew tired, they had less access when pressing Celtic’s wingers, who could flex their dribbling abilities properly for the first time. Indeed, it was Rogic and his own 1v1 abilities, who proved to be the difference maker in what was an enthralling contest between the traditional and (hopefully) future styles of Scottish football.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen