Build-up under Roberto de Zerbi: An early analysis of his Shakhtar Donetsk

After finishing 2nd last season, Shakhtar Donetsk hired esteemed, upcoming Italian manager Roberto de Zerbi. The ambitious and unique playing style demonstrated most notably at Sassuolo earned him acclaim for his tactical acumen, ending his tenure at the Sassuolo with an 8th place finish and a respectable 62 points. This article will investigate the rationale behind his build-up preferences and how that is translating to his new side.

The base

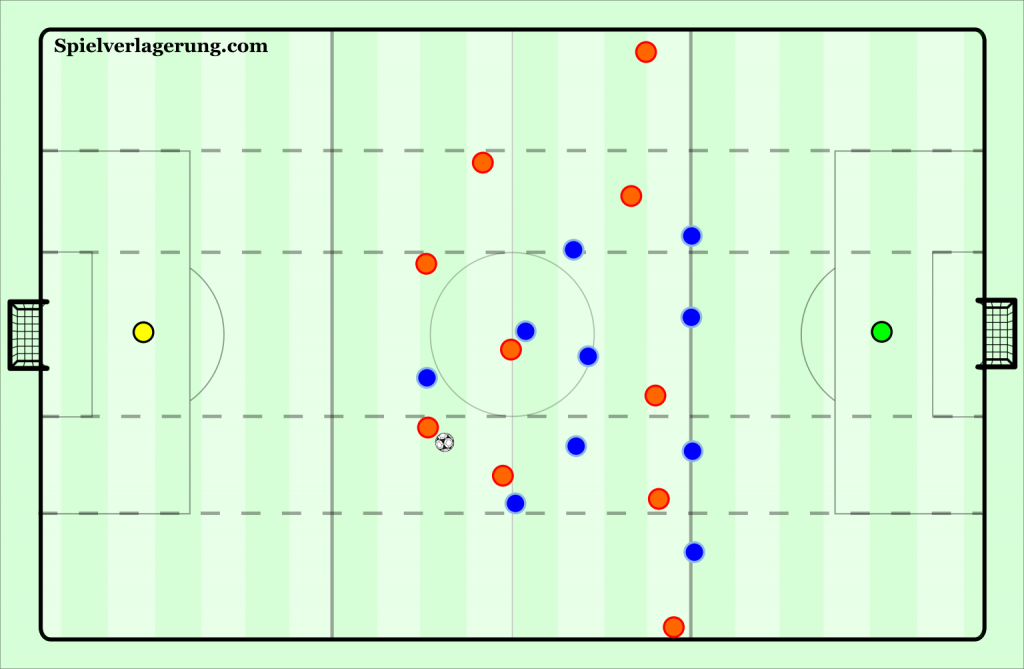

High pressing teams are seldom seen in the Ukrainian Premier division; thus, it seems logical to begin the discussion of possession structures under the assumption of the opposition playing a mid-to-low block which allows consolidation of possession until approximately the half-way line, which is when frontal pressure is initiated to varying degrees. However, that does not preclude discussion of deeper build-up more generally, with extrapolations from the glimpses seen thus far, in addition to strategies displayed at his former club, Sassuolo, being sufficient to create an understanding of anticipated deeper build-up, which is more tangential now in comparison to his time in Serie A.

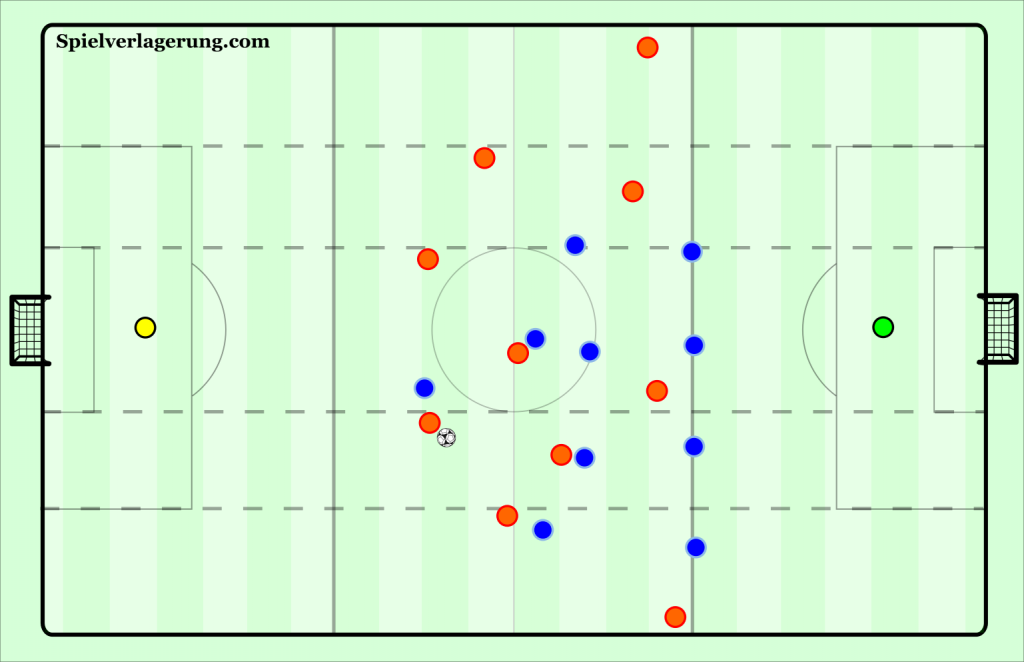

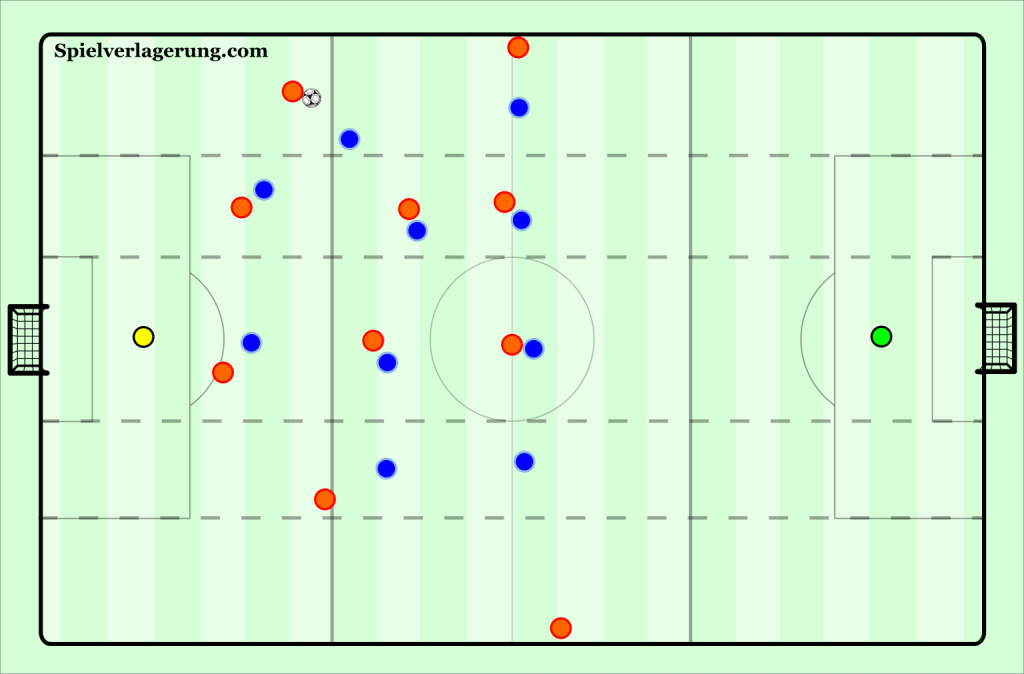

From the consolidated phase of half-way line possession, Shakhtar use a base 4-1 (or 2-3 depending on semantic preference). The shape is centrally compact, as transitioning from deeper phases a defensive midfielder, typically the left sided player, moves into deep half-space zone, although rarely lateral to the defensive line. The far-side full back simultaneously compacts centrally, creating a latticework of potential central passing connections. The theory underlining this is the desire to maintain central control, which permits a greater degree of control holistically due to the increased difficulty of opposition pressuring. Defending can abstractly be conceptualised as a coverage and compactness conundrum with the opposing side having to balance the two aspects in the nominal sense. Simply, the more the pitch is covered, the less compact the defensive shape is, creating spaces in between the lines; however, spatial coverage remains important to prevent easy opposition occupation of spaces, with a higher degree of compactness creating a higher degree of control within said prioritized spaces but lessening control of other spaces, which is pertinent if they are accessible. Hence, teams seek to reduce the effective space available to the opposition, seeking to cut passing connections to underloaded or spatially uncovered zones.

The typical response to this conundrum is for the opposition to prioritise central compactness (horizontally and vertically) to prevent central infiltration in between the lines, thus theoretically pistoning play to wider regions where the touchline can be used as a constraining force to reduce the effective playing area, increasing the chances of a turnover being generated. Therefore, maintenance of maximum width is paramount to understanding the methodology of de Zerbi, as the two touchlines in build-up play are always occupied. This helps creates outlets on the flanks which is where players are most likely to be free, and progression is most likely to occur, in addition to increasing their relevance to opposing defenders, potentially undermining central compactness. Microcosmically, in these wide areas, full backs are often presented with this coverage/compactness conundrum, as if they get tight to the touchline player, they make their ball reception more difficult and undermine their ability to function as an outlet; however, they accordingly increase the space in between themselves and their centre back which can be infiltrated, making this tight tracking the wrong decision during central possession, and rather an aspect of half-space or wing possession when the defensive block can shuttle over to reduce space in between the lines as the far-side becomes less accessible for the team in possession directly, and thus can be left spatially underloaded to aid in compaction attempts.

At Sassuolo, particularly when facing rigidly man-oriented teams such as Hellas Verona or Atalanta a common manoeuvre employed was to split the centre backs, who would be followed unquestioningly by their respective markers to generate central space for the goalkeeper to progress into (or receive from a static position, often from a back pass after struggling initially to break down the man-orientation without goalkeeper involvement). This would allow for this direct inward infiltration through a dropping forward, being tracked vacating deeper space centrally for the wide winger to eventually run into once the pass into space has been played. This could generate a 1v1 directly from goalkeeper possession with the player being able to cut inside onto their stronger foot. This exploited this tight tracking of the wide outlets by using an incisive inward pass where the dynamic superiority of the attacking runner would allow them to receive the ball provided the pass was accurate.

Through emphasising maintenance of central control, Shakhtar force the opponent to cover a greater extent of the pitch and make pressing difficult due to lack of constraining forces and a myriad of potential passing options being available. Any concerted (direct turnover oriented) pressing effort at this stage of possession would likely engage in a degree of man-orientation to limit the potential for receivers from exposing poor compactness between the 2nd and 3rd lines necessary to engage like so, while additionally seeking to use backwards reception as a compaction tool for containment because of the limited progressive options forced by tight marking having a similar effect to the touchline, but vertically rather than horizontally limiting access to 180°. The danger in initiating a higher press during these circumstances, is that poor spatial occupation caused by the compaction attempt could be tool easily exposed because of the difficulty in matching Shakhtar’s numerical commitment which creates free men in addition to the presence of outlet wingers who are accessible through narrow full backs, or if forced, potentially through a higher sitting goalkeeper acting as the free safety circulation option (this is less prevalent at Shakhtar compared to Sassuolo, although, that is down to a reduced prevalence of high pressing which provokes the goalkeepers inclusion). Although, when pressed like this central infiltration via tight passing, using the creation of new passing angles created by subtle staggering attempting to remain ahead of the opposition in relation to the ball has been more common, and is perhaps why opposing teams are so reticent to attempt to force a deep turnover, but rather force discomfort. Essentially, engaging intensely at this stage of possession lacks the constraining mechanisms against Shakhtar’s compact build-up shape, where they can tightly circulate to find an open passing angle to the increased space in between the lines.

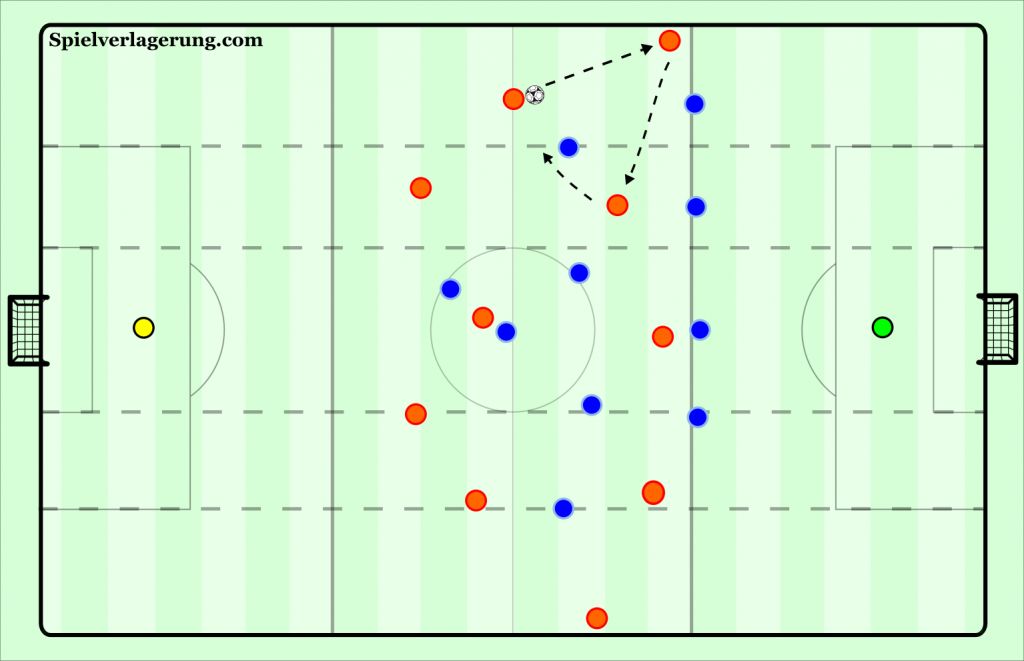

A consequence of Shakhtar’s narrow build-up shape therefore is the creation of an outlet in the winger (width holder being the more neutral term to interchanges, throughout, I may refer to this player as both), who upon reception, because of the solidly established connections experience a reduced inertia time between ball travel. The result is they are typically unpressured and can receive with time and space. It should be noted that there is a ball-side response with regards to full back positioning as they widen in accordance with the ball while still maintaining a degree of narrowness inside the half-space – the diagram represents central consolidated possession. In essence, the maintenance of full effective pitch width means the wide forward players are always within 2/3 passes of ball reception, while the central commitment forces the opponent to remain centrally compact until the ball is circulated due to overzealous pre-emption extending the gaps in between the lines, allowing for more advantageous central infiltration.

“Who are our unstoppable guys…”

This is where the concept of the qualitative superiority becomes pertinent to understanding de Zerbi, as the isolation of the winger against his opposing full back in wide regions to progress via a duel, or a threat of a duel on the last line is a common route of progression. The underlying theory behind the qualitative superiority is that, using the principle of not all situations of numerical equality being equal, teams can attempt to manufacture positions where they can have their better players isolated as to exploit the circumstance of ‘real’ terms inequality. The 4-1 therefore seeks to manufacture advantageous duelling circumstances if the opposition defend with a degree of semi-passivity (think, 4-4-2, two forward pressing players, near side forward pressures ball carrying centre back and carries forward run if passed laterally while the far-side forward orients himself pivot player) which is the typical response, if preventing central infiltration is the primary aim of the defensive side, which if possession has reached this stage rather than being engaged in higher regions, is a reasonable assumption. For this set-up to be maximally effective therefore, when posing the question, “who are our unstoppable guys…”, as Pep Guardiola did in Martí Perarnau’s Pep Confidential, the answer should be a winger, and this is true in the case of Shakhtar as it was for Pep, with Manor Solomon having the dribbling oriented skill-set which thrives in duelling conditions, while additionally having the agility and close control to infiltrate tight spaces when centralisation is necessary, being comparable to de Zerbi’s previous ‘unstoppable guy’ Jérémie Boga in his willingness and proficiency in engaging in offensive duels.

Reasonably, there is scepticism surrounding the existence of the microcosmic individual duels in football because there are a manifold of influencing factors determining the conditions of the initiated duel, such as the aforementioned central compactness to generate space, but even within this concept of the initiated duel, the players partaking in said duel, still need to consider factors external to it, such as passing options and space to defend which highlight the interdependent nature of the sport. I do not think; however, that the lack of absolute isolation precludes duels not existing, rather, the conception is more akin to, if you can give this player time and space while occupying other defenders, the situation can generally be considered advantageous because of his take-on proficiency. Opposition knowledge of take-on proficiency moreover alters outcomes because it encourages a reticent approach which seeks to gather supporting teammates to limit the time and space available to the duellist. In this instance, his skillset can be considered to produce positive externalities of allowing gained territory which can allow better sustained pressure and final third consolidation, in addition to other aspects such as potentially lowering opposition central compactness, or encouraging a greater degree of ball-sidedness to attempt to mitigate the players strengths.

The supporting mechanisms of the wide outlets, additionally highlight the value of the 4-1 structure in generating conditions conducive to their thriving in addition to aiding the important overarching aim of wide progression, which serves as a reminder that the qualitative superiority is a means rather than ends.

Accordingly, de Zerbi’s football highlights the effectiveness in implementing positional play wide dynamics which encourage frequent rotations. This uses the five-zone model (7 as a more in-depth ball-side accurate guide), and broadly, as a heuristic suggests the full backs and wingers do not occupy the same vertical corridors, rather one typically occupies the half-space while the other the wing. Oftentimes, because of the 4-1 set-up narrow-wide full back movements are seen complemented by wide-narrow winger movements, and having a pass laid off to him by the near-side centre back can allow for progressive reception from a diagonal pass to continue moving into the free space upon reception to carry forward momentum into his pass and run. This generates an advantageous situation because the initial narrow full backs facilitate the central possession which allows for the isolation of the winger to receive, where the assumption is that he is the ‘unstoppable guy’, hence, receiving with space is valuable. Subsequently, the rotation ensues progressively which has a discombobulating effect on opposition marking, with the winger having the potential of infiltrating centrally, thus drawing the intention of the full back who has presumably moved wider to engage (if this does not occur, the rotation is unnecessary, until it does, with the full back being inclined to stay narrow, then offer a threat via an underlap). This is where the duel can occur. The narrowing full back opens space for complementary movement of the full back, to then occupy the wing zone. Such complementary movement is often difficult to track in a man-oriented fashion because the attacking player constantly has the initiative, often resulting in the full back having to deal with a 2v1. The rotational permutations afterwards are difficult to detail because of their reliance on contingencies: in the example below, one could imagine the inverting winger looking for a 1-2, continuing his run inside, the forward player offering a run in behind etc.

Should the full backs attention be drawn more towards the prevention of the complementary movement, central infiltration can occur, where rather than continued direct progression to engage in a duel with the centre back, more lateral movement to expose the underloaded flank with a pass to the far-side width holder either directly or through a conduit. Oftentimes to aid this dynamic, the centre forward can make a ball-side run to draw the attention of the ball-side centre back to allow for a greater degree of centralisation which secures greater access to the far-side. This is where the benefits of half-space infiltration through going around the compactness is demonstrated. René Marić divulges into the details of the benefits; however, broadly it is a challenging situation to defend because the player has access to the near-side wing, middle and far half-space in addition to himself occupying the half-spaces which makes compact defending difficult. Ergo, the link in the far-side half-space is often positioned deeper in the form of the full back, who because of his depth can often receive with greater ease which amplifies the threat of his reception, as that makes the underloaded side available and because of the dynamics, will often force a defensive state of retreat. Thus, the principles remain effective in the final third where the opponent are even more likely to prioritise central compactness, and where breaching the last line causes a defensive state of retreat where the opponent are reacting to newly introduced space by deepening, where if slow, a drilled cross can be dangerous, or otherwise going backwards can allow for a shot in and around the D. The overall idealised move switches from side to side via vertical corridor rotations and half-space links which seek to optimise the role of the wingers, who can come narrow when the opposition are less structured and thus be more effective while initially being wide to receive with greater ease against a compact centre.

This narrow-wide full back, wide-narrow winger dynamic seems to maximise time in possession for both players during the attempted progression while simultaneously ensuring a greater degree of central control. To elaborate, the space in between the oppositions 2nd and 3rd lines in the half-space during central-to-wing possession is often congested which makes ball reception and subsequent manoeuvring difficult which means the situation is not conducive to the duelling qualitative superiority attempting to be manufactured. Thus, to maximise the time the winger has available, he is better suited out wide, thus in accordance with positional play, the full back occupies the half-space which compacts deeper play. They can then receive diagonally, moving outwards which naturally opens the passing lane to the winger in addition to the continuation of their run which draws the full backs attention granting the winger more space inside as a conundrum is created for the full back who was previously stepping out to engage. Winger and full back in this were used as abstractions of typical positioning rather than the nominal role possessing, a unique characteristic for this dynamic to occur. Full back refers to running from the 1st line; winger = in between the second and third or on the third line. This is an important caveat because, as noted, Shakhtar from consolidated phases drop a defensive midfielder into the first line allowing the near-side full back to push up.

To understand these concepts better, I would recommend attempting to watching the first goal against Inhulets which is a classic 4-1-5 sequence highlighting its strengths. Compact the play (note prior conscious effort in its achievement – players deliberately moving inwards while in formation) and link via defensive midfielder wall pass to better connect centre backs (more advantageous ball reception, receiving directly onto the side desired to build down rather than having to allow the ball to roll). Access isolated winger to engage in a duel and infiltrate inwards. Get in between the lines through playing around, achieved through compacting the lines horizontally in the build-up phase through narrow shape, hence making the task of going around easier while maintaining connections around. Manor Solomon, as the ‘unstoppable guy’ is isolated, and demonstrates title is justified.

However, particularly against teams which expose more space in between the lines because of their more active set-up, there is utility for having an ‘unstoppable guy’ in the interior spaces, particularly as, due to the aforementioned compactness coverage conundrum generating additional space due to the horizontal stretching consequent from effective maximal width. When the near-side deep half-space occupier has possession in the 4-1, he has good access to the width holder, which could draw attention, reducing compactness, thus allowing for direct infiltration in between the lines, or if reception is allowed, allow for quick link-up if the interior staggers as to create distance to the last line of defence, to create space to receive. Remember as mentioned earlier, being wide to receive with greater ease against a compact centre is the primary benefit, thus if that centre lacks compactness, vertical or horizontal, wide positioning of the ‘unstoppable guy’ becomes less pertinent to create space for him. Duels can occur in the sense of tight marking, where you want Solomon, Pedrinho or Tetê to be the player receiving because of their capacity to receive on the half-turn, evade pressure and wriggle away from the opposition, exposing the uncovered space which resulted from the attempted tight marking. Thus, against Genk for instance, Solomon occupied the half-spaces more frequently than against Inhulets because the potential to be dangerous was greater resultant from Genk’s man-oriented style of defending in contrast to the prioritisation of central compactness which crowded out the half-space and encouraged possession down the flanks.

The occupation of the half-spaces directly essentially ‘skips’ a step required against deeper opponents in that the dangerous player is already more central to drive at the opponents last line, rather than having to manufacture that space through a duel, while nonetheless retaining the complementary full back run and access to the underloaded side which makes balancing the compactness/coverage conundrum difficult for the opposition. Solomon’s ball reception pulls people into his orbit, which requires skill to evade and exploit the poorer spatial coverage consequent – this will be discussed in greater depth when referencing the half-space diamond. The defensive midfielder tucking in has occurred disproportionately on the left flank thus far, thereby pushing the full back forward and Solomon inwards. I anticipate Solomon will occupy the half-spaces with a greater degree of frequency in comparison to Boga, as his skillset is more attuned to tight spaces, and therefore he has greater potential to be dangerous. The reason for the additional focus on the isolated wide dynamic is because it encompasses many of the concepts such as the half-space to half-space switch, just with an additional degree of complexity in addition to this concept remaining a potentiality on the right flank where the half-space player is typically deeper to gain more space for reception.

Tangentially, one could imagine a scenario whereby pushing forward a member of the double pivot in between the lines is beneficial when transitioning from the 4-2-4 shape rather than the left-sided defensive midfielder as displayed by Shakhtar. What matters is that the spaces are occupied, and players are placed most optimally from a qualitative perspective to maximise their skillsets.

I have opted for the term ‘complementary movement’ thus far to describe the rotations because of the increased frequency of underlapping runs to achieve the rotation, particularly from right full back Dodô. The underlapping dynamic is especially effective against teams that sit deeper such as their first competitive opponent Inhulets, where central infiltration via dribbling is more difficult if only the wide players are uncoordinated, which is what the overlap provokes. Rather the underlap against a team prioritising vertical and horizontal central compactness serves to discombobulate more players, as more opposition players are within their sphere of influence. The run will be tracked temporarily by a midfielder before getting passed on, hence causing more disruption to spacing which the winger can exploit by dragging the midfielder deeper, opening previously covered space centrally as the compaction caused by the underlap worsens spatial coverage. An overlap is predicated to a greater degree on overloading the wing-back, and itself is a more direct threat because of the more favourable circumstances for ball reception (easier to directly cross when running from the outside, which, in circumstances such as these is dangerous because the last line has been breached, thus, the opposition are retreating while attacking players are running with momentum into the box). The decision about preference is all about considering trade-offs. Positionally the underlap is more advantageous, but danger-levels increase with the overlap. I anticipate the underlap will be more common in the Ukrainian Premier Division as the opposition who sit deep will be too compact and numerically committed to permit for effective deep overlaps initially from build-up. Final third after circulation, overlapping conditions may be more conducive because opposition previous ball-side commitment leads to an underloaded full back. Thus, it is fair to characterise the underlap as more profitable in consolidated sequences (building against an organised low block from centre back possession) and overlaps in more transitional circumstances which require a more active opponent for space to be exposed. However, as shown against Sheriff Tiraspol, the underlap is not a panacea, as in their 4-5-1 mid-to-low block, they had the numerical commitment in addition to wide coverage to close wide and central progression avenues and were often able to constrain following an attempted pass to the underlapping player, who was too wide to create new forward passing angles. Therefore, reliance on this strategy can generate issues with regards to progression against teams with a 5 at the back or in midfield with man-oriented covering mechanisms.

Deep block solutions

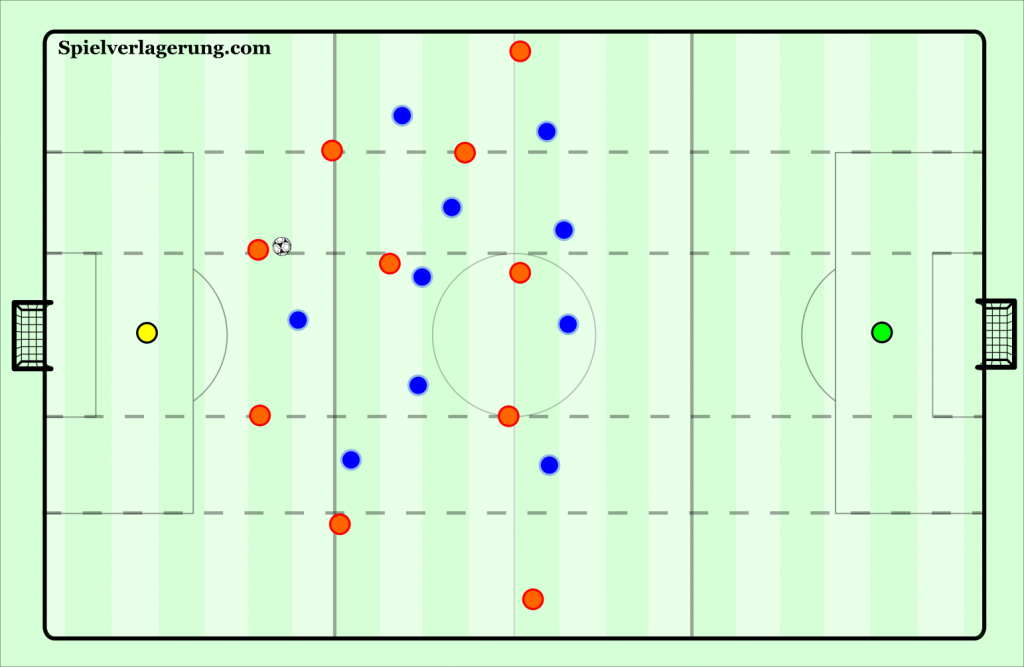

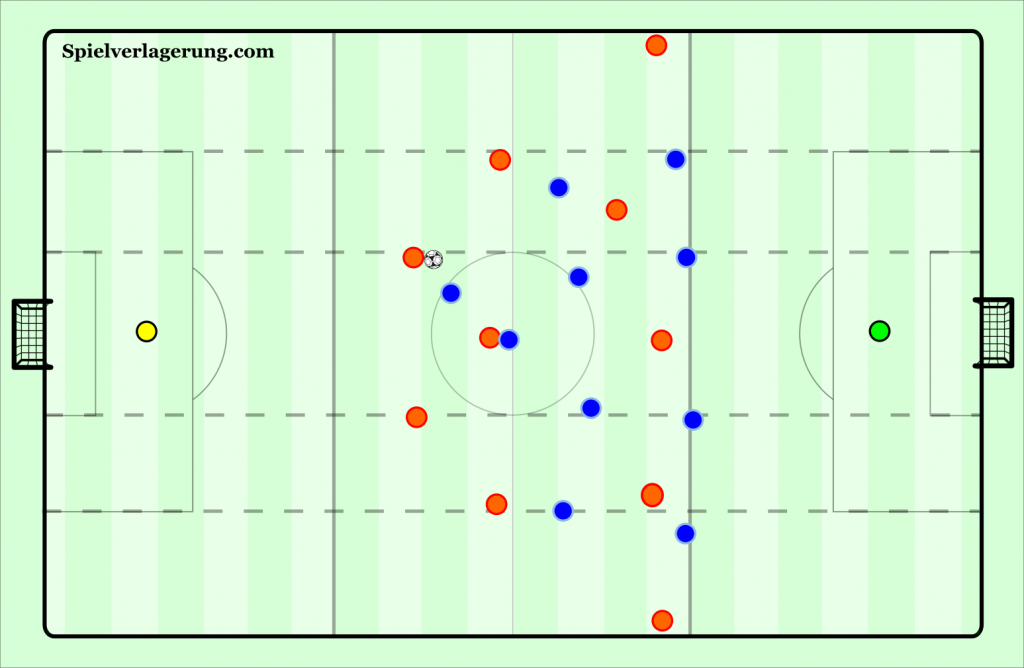

An alternative when sustaining pressure against a press as passive as Inhulets for example is to transition to a 3-1-5-1 attacking shape to achieve full horizontal convergence in between the lines and presenting an avenue for last line breaching directly down both flanks, exploiting the lack of pressure on the ball.

This creates an environment more favourable for tight interplay between the attacking central midfield players in between the lines which permits a more sustained presence increasing the extent to which oppositions defence is being manipulated as they attempt to converge, but unsuccessfully because the short distances between the many options allow for possession circulation, creating opportunities the expose the defences last line, or craft a shooting opportunity. The oppositions centre backs and midfielders attempt to converge on the players which makes threats in behind more dangerous for short moments because of the lack of synchronicity associated with man-oriented stepping out triggered often by ball-reception or plausible direct ball reception leading to exploitable gaps where spatial convergence has been reduced whereas the dropping midfield makes dropping Shakhtar players and the pivot have more space in possession due to reduced spatial coverage, increasing their chances of finding the player and easing the process of ball circulation high up, with the contingency option of moving backwards, consolidating and attempting infiltration again.

The diamond build-up shape is sufficient for circulation against a passive striker press, such as those seen in 5-4-1 low blocks. It permits consistent control while holding the potential to open new avenues of attack as the half-space players are well connected. The deep central option acts as the connector while the defensive midfielder now has more progressive responsibilities compared to the 4-1 where he acts to a greater extent as an option for wall passes and importantly acting as the support once progression has been attempted to the players in between the lines. While the inward option for initial progression from the wide centre back can open advantageous passing angles to exploit wide midfielder on wide centre back pressing due to the small space opened being quickly (if not previously) occupied. This increases the utility of centre back ball progression to entice the opponent to step out. The central players circulating are primarily tasked with creating optimum reception conditions for the wide centre backs where the direct pass threat out wide or dribble is possible to exploit any remnant of opposition ball-sidedness prior to circulation or lack of spatial coverage due to central compactness. The wide centre backs can seek to ‘provoke the proximity’ which in essence seeks to overload a player through progression and establish a very short but strong passing connection to exploit that overload. Move the ball to move the opposition: capitalise on potential transitional moments through increasing the speed at which consolidated moves to transitional through the provocatory centre back pass (diagonal and forwards, similar to the deep full back in the 4-1 regarding optimal reception).

Additionally, it should be noted that after a failed transition this shape is more common as both full backs have already committed forward, while, because of the wide emphasis for progression but central focus concerning consolidation, the double pivot and two centre backs have maintained their shape to allow for central connections to be maintained which prevents opposition constrainment at the touchline by offering a backwards safety and circulation option if pressure is intensified or avenues to progression cut. In essence, rather than awkwardly re-establish their deeper consolidated possession shape of the 4-1, they attempt to sustain pressure in the opposition’s half through the greater spatial occupation in between the lines hopefully having a pinning effect as the players encourage opposition compactness and therefore reticence to pressure, because the diamond is still able to access allow vertical corridors.

Another alternative used against a 5-4-1 for similar effects is the 2-3 set-up with the deep narrow full backs placing themselves in a more advanced position, evocative of the classical inverted full back. This damages the connections to the flank in that the secure pass through the conduit of the full back with possession to the wide player (to attempt complementary movement) is no longer available due to reduced time and altered body orientations (backwards rather than forwards diagonal due to increased proximity to opposition wide midfielders). The advancement is provocatory to the wide midfielders, so serves a central discombobulation purpose, hoping to open space in between the lines to infiltrate through the centre. They much like the pivot; they act as walls of circulation attempting to draw pressure. I imagine this will serve greater utility against a passive 4-5-1 structure where access to the half-space is zonally blocked, while direct wide progression is difficult because of the midfield coverage, requiring positioning that disrupts the opponent on the 2nd rather than 1st line, which simultaneously allows them to work as wall pass options to open more advantageous passing angles to the centre backs to infiltrate.

Finding the far-side CB and exploiting the underloaded side

Thus far, discussion has been rather theoretical and principled, which while necessary to understand the underlying ideas, does not fully encapsulate Shakhtar. Moreover, moving to a 4-1 shape for circulation is not some panacea, rather, details are necessary in how to circulate possession to exploit the advantageous aforementioned. Particularly against higher pressing teams, such as Genk and to a lesser extent Lviv, a key concept which has come to fruition has been the finding of the far-side CB from consolidated phases of possession and the methods used in its achievement. For these sequences to be initiated, typically the oppositions forward must pressure the ball carrying centre back or if building backwards, still the opposition would have had to commit to the ball (now far) side.

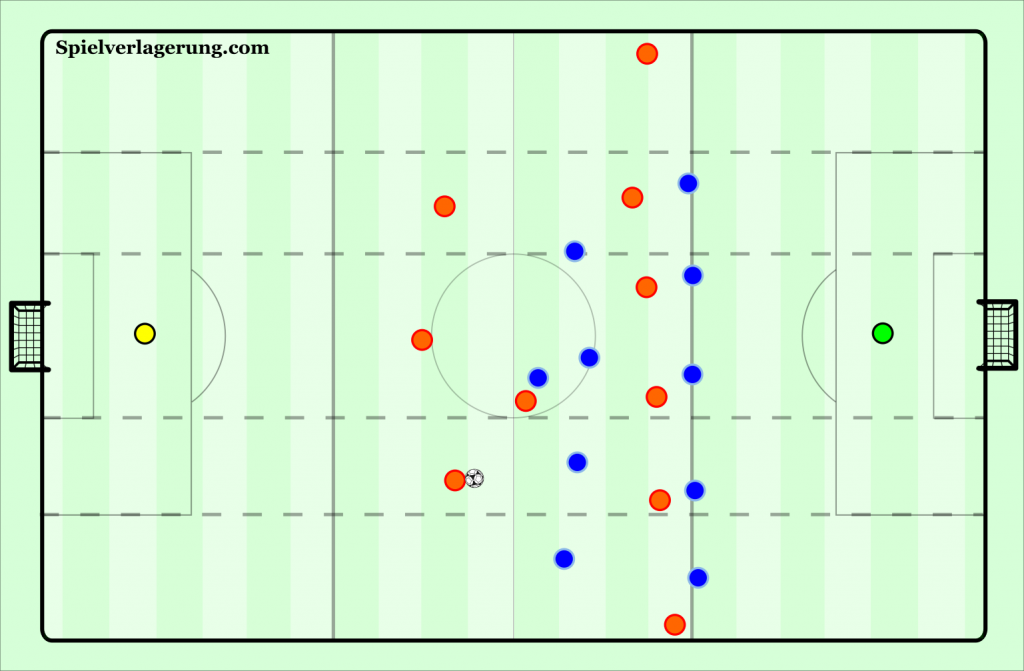

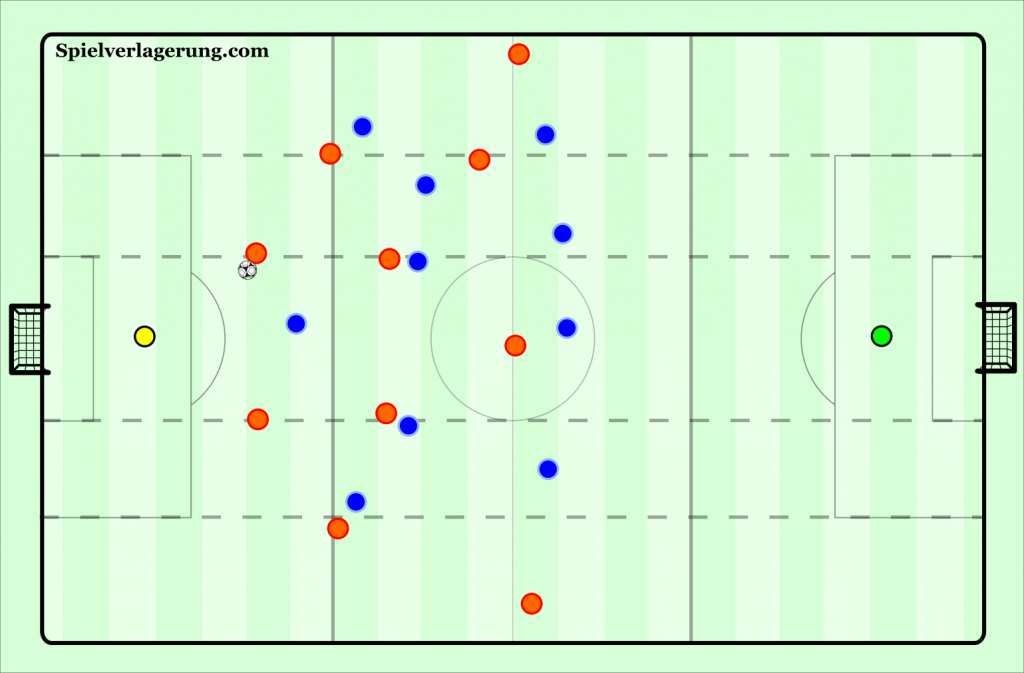

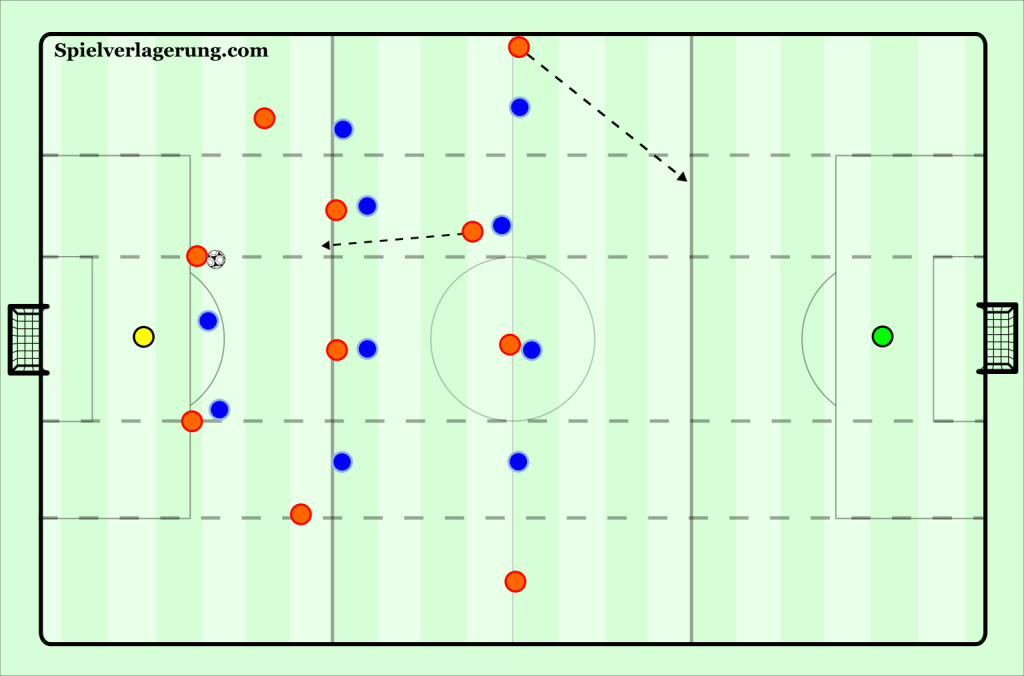

Firstly, against passive opposition, typically the single pivot acting as an option for a wall pass is sufficient for circulation, not requiring the later complexity. The passing triangle centrally in conjunction with half-space occupation against a narrow 5-4-1 defensive structure is noteworthy because of its negation of central pressing efforts. The centre backs can hold possession uncontested, and often bait progress to draw the centre forward away from the defensive midfielder. Any tight marking pressure from a midfielder stepping out (onto the pivot) is superfluous because there is constantly a free backwards option meaning it unnecessarily exposes space. The wall-to-far-side-centre-back-route creates advantageous passing lanes and progression circumstances due to the newly infiltratable space caused by the misalignment of the defensive line. This against especially horizontally compact sides can be useful in opening the half-spaces with the centre back being able to receive possession to the ball side directly without letting the ball roll (lowering the inertia period, meaning the opposition have less opportunity to shuttle), where the now advancing deep half-space occupier can move forward, receiving diagonally and progressively from the centre back, thus allowing him to swiftly link up with the wide and interior players because of the carried momentum of consistent progression.

Against more active opposition, such as a forward pressing 2, where orientation is typically pressure ball-side centre back to follow through on the far-side while the other forward orients himself around the pivot allows for more interesting machinations. A common example of this is the narrowing of the near-side full back once the shape has been formed, which I am particularly fond of because its uniqueness, being a unique facet of the 4-1 build-up shape with its narrow full backs. This makes it difficult for the oppositions forward to simultaneously cut the passing lane to the far-side CB which is now accessible via the pass to the near-side full back while maintaining ball-oriented pressure ball-side centre back. The full back in such a scenario is typically the responsibility of the opposition’s wide midfielder, who maintains distance because of the depth of the full back does not permit engaging proactively but rather reactively to maintain compactness centrally until an isolating opportunity arises. Thus, through narrowing, the full back escapes his purview to a greater extent, whilst also carrying the initiative which essentially certifies ball reception because the ball-oriented direction of the strikers pressing means he won’t be able to block or intercept as he is running laterally. The degree of staggering for this to be achieved has to be sufficient that the full back is not near lateral to the centre back during its occurrence, which is typical, as too close a distance to the centre back vertically would allow the opposition forward greater opportunity to intercept.

This similarly allows for advantageous reception the far-side centre back, as he is receiving onto his wider foot directly, and in a manor favourable to an outward facing body orientation which allows for greater exploitation of the underloaded far-side. This creates time and a series of numerical superiorities to exploit. The first phase is receiving CB, deep half-space occupier, interior and width holder which permits initial progression against the opponents wide midfielder, full back and potentially centre back whilst in the second phase – assuming they select the typical option of prioritising central compactness, which for lack of desire but potentially unavoidably imposing objectivity, is the ‘correct thing to do’ (at least according to traditional conceptions, where, for lack of desire in this instance to get bogged down in an tangential metaphysical debate about the validity of ‘objectivity’ in football shall be left unquestioned) creates a 2v1 overload (classical 4-1 dynamics discussed in theory) on the full back allowing access in between the opposition’s lines through going around in addition for the potential for an underlapping run and consolidation of possession higher up. To explain the last part, should the underlapping run be tracked (assuming the pass is to the width holder who has the most space), and a dribble inside does not become available which would permits more decisive attacking actions, the potential to while to move backwards remains, albeit against a consolidated opposition defence in contrast to the transitional state faced by the unpressured full back, which means worst case scenario the result is typically gained territory and an ability to circulate. Within this there are many permutations depending on extant opposition reaction; with openings in between the lines potentially being available directly from wide CB possession for example if central compactness or man-coverage on the player cannot be achieved. However, the FB narrowing, finding the far-side CB which allows for a pass to the width holder who has complementary interior underlapping is theoretically, the most likely positive result from this sequence.

Against particularly man-oriented opposition, such as Lviv, the full back can practically reform the double pivot, as the tracking of the single pivot results in him widening his position to create the space he gradually drops into the defensive line. This reminds me of a concept practiced frequently at Sassuolo whereby the far-side pivot player would come centrally to open the passing lane to the far side centre back whilst the supporting opponent is oriented to a greater extent on the lateral (ball oriented centre back-to centre back type pressing). If he is pressured by either the midfielder or more likely the wide midfielder space opens while the backwards orientation of the pressure is not particularly pertinent because it does not prevent accessibility to the far-side CB who can now execute an up-back through sequence. Access is manufactured to wider regions. The opposition are overloaded theoretically as the wide midfielder cannot initially simultaneously cut the wide and IBTL option. Wide option likely therein initiates the rotation. The aim and consequences are largely the same as previous instance, just the extent is increased. This can be considered the switching of deep midfielder responsibilities in the 4-1 (pivot goes to deep half-space occupier and vice versa. Imagine a pendulum).

The next step against opposition high pressure is the dropping of the interior, where the pass to the pass to the near-side FB to open the angle is problematic to due opposition tight marking pressure making ball reception difficult, with increased proximity of marking player increasing the chances of a turnover occurring due to the opponent being able to more easily compact. The other, perhaps simultaneous factor to consider is staggering, as if the full back is more lateral to the centre backs, performing the pass becomes more difficult due to increased chance of interception – with this potentially being triggered by a close marker to generate better conditions for receiving the ball, or otherwise make conditions more conducive for this pattern. The dropping of the interior to access to the far-side centre back is analogous to the reforming of the double pivot, and considering vertical positioning, the easiest route behind its achievement. Thus, the 4-1 shape allows for adaption against opposition pressing triggers which result in an alternate style of defending than initially implied by mid-block set-up (either employed from the start or formed due to the initial press being beaten and a restructuring occurring). Because the dropping player carries initiative over his man-oriented marker he is typically able to receive under sufficient pressure to prevent any direct progression, whilst nonetheless being capable of playing a wall pass.

This sequence functions much like an up-back and through rhombus, whereby play is intentionally contracted against man-oriented sides because the end-goal is envisaged, using the superior knowledge present in automatisms to avoid and exploit compaction. The tip is the interior receiving, with the opponent forming a compact box around the four players but leaving their far-side player in a potential 2v1 situation when the passing angle opens. This example is predicated on Genk’s pressing set-up of a narrow, man-oriented 4-2-3-1 where the wide players are responsible for the full backs or the far-side player the centre back because of the numerical superiority granted by the 4-1 meaning the furthest player in deep build-up should go uncovered. It should be noted, that although the pressure is often escapable, it still impacts technical play, with the pass more likely to be overhit because of the onrushing player and the speed at which the pass must be made due to the opposition’s compactness. Although, this occurs in other circumstances where access to the near-side CB is poor or dangerous, with that being the key trigger to drop. While it is still preferred to the centre back lateral to find the far-side CB as the up-back essentially removes a potential pressuring player by drawing him to compact and preventing the continuation of a pressing run as he needs to maintain the vertical pressing lane on the near-side centre back. Ergo, permitting centre back ball progression unpressured into the space to access the underloaded flank.

The checklist seems to be something like this therefore:

- If wall via pass is accessible to find far-side CB, use it

- If unavailable, the ball-side full back should narrow and stagger more towards the 2nd line to open the passing lane, bypassing the pressing 2 oriented around the pivot and ball-side CB.

- If a wide midfielder marks tightly t or otherwise staggering makes it impossible, the interior player should drop, opening access through a wall pass.

- If all access is cut (typically occurs after reconfiguration and 3-1 against a higher pressing set-up), attempt to find the wide outlet directly.

Half space diamond

Prior to moving into their 4-1 build-up shape, Shakhtar use a double pivot with the full backs both being wider, although not hugging the touchline, to progress linearly backwards, I will discuss the theory behind the shape and reasons for the change later, for the time being the focus is on the transition.

Against more passive opposition which prioritises remaining centrally compact, the shape transition (the stage between stages, rather than consequent shape) is not particularly interesting. However, against Genk who, while passive during this stage (post deep build-up progression) maintained the fairly active progression blocking strategy of central man-orientation on Shakhtar’s second line. Attempting to nullify Shakhtar’s strengths by forcing direct play, cutting all direct short options to the ball carrier. To solve, this, Shakhtar used a half-space diamond.

The theory being, progressing is easier as there are three forward passing options available which pose a microcosmic coverage/compactness conundrum due to the left and right options splitting tight markers opening the vertical, while closing the vertical via compactness leaves the left and right open, making the imperfect solution tight marking, as a lateral pass made possible from the tight marking opens access in between the lines, potentially exposing the poor spatial coverage. Therefore, the passivity of the opponent on the ball carrier should be exploited to create to shape, to infiltrate in between the lines. In the half-space diamond (both during and after shape transition) you want the interior player, or tip of the diamond to be your ‘unstoppable guy’ because of the space available in the half-spaces after reception, the requirement to drive and opposition and evade tight marking and generally, the want to actively engage the opposition defence which requires a high degree of duelling skill.

This is where the initially wider positioning of the full back’s become pertinent as the opposition wide player was oriented around him and thus has wider positioning due to requiring greater first line coverage, meaning the distances between himself and the ball carrying centre back is larger, preventing out-to-in pressing. Meanwhile, the centre forward occupies the ball-side centre back preventing him from tracking, resulting in the half-space tip player being free to receive with space in between the lines. The movement more generally has a discombobulating influence on the opposition’s defence as man-oriented responsibilities are altered by player movement which is pertinent as time is crucial in tight marking scenarios to prevent over-extending via compensating, creating a worst of both worlds situation where ball reception is easy, and space is uncovered.

Codified it is something like:

- Defensive midfielder drops

- Full back pushes forward

- Winger can come narrow to form the diamond

This dynamic can occur from more static 4-1 play additionally; however, the dynamic is altered by the greater degree of initial horizontal compactness, which makes the sequence tighter. The movement of the player at the tip starts from a more static position meaning he already has a responsible marker which places a greater emphasis on the role of initiative, key against reactive man-orientation. Against such defensive set-up’s Shakhtar have the ‘dynamic superiority’ which Judah Davies eloquently describes as “both superior timing (through initiating the movement) and superior speed (due to having more momentum as they began their run earlier) to their opponent.” I would add to that description, superior knowledge of the permutations if the move is automatised, which allows the players to act quicker, and more decisively, in addition to facilitating beneficial movements such as third man runs which are predicated on implied subsequent actions. The dropping compacts play further vertically, meaning play occurs on the fringes. However, this is common in automatised play, because it thrives of creating maximal possible compactness to expose spatial coverage. The half space player knows he will drop under these conditions, that he will have supporting players to the left and right which grants him superior knowledge to work from. The pressing from this circumstance is more likely to be out-to-in from the near-side winger who was responsible for the static dropped midfielder (narrower than transitional as well, making time of the essence). However, the same principles apply as far as the diamond opens space for the lateral in between the lines, irrespective of distances, and as the player has committed to pressing, the passing lane should be open. This however only works if a 4v3 numerical superiority can be achieved which means whatever player is pressing the centre back has left space open in between the lines. It all varies depending on opposition positioning as well, because sometimes cover shadows can be counteracted through the up-back but generally larger spaces are required for this to work. The important takeaway is the concept of a half-space diamond as well as coupling it with other concepts such as the wide qualitative superiority generating more space than is typical because of the threat of 1vs1 scenarios. The 4v3 situation mentioned mean seem like a cop-out, not creating the least convenient of possible worlds, which is most useful when detailing concepts in the abstract; however, much like the previous example, effects such as pinning and the defensive desire to maintain a defensive +1 so the game does not descend into a game of transitional chaos where other forms of positional manipulation could be used, and the rhythm would be different is pertinent to consider. Deep supporting movement to open previously covered spaces via cover shadows compensating for defensive numerical inequalities is a reasonably reliable mechanism when play is structured such as Shakhtar.

However, a seemingly less convenient world, is that whereby the interior player at the tip is detached from compact three because of a failed transition, while his initial initiative which took him away from his marker to get in between the lines, now results in his marker having a cover shadow, while being vertical to the ball carrier, and the two wide players are compact and in close proximity to their respective wider players of the diamond. Because the diamond is not isolated, but rather benefits from external factors, the defensive players must retain their cover shadows as the tight marking of other players outside the diamond is not sufficient to prevent access to the interior player at the tip because it only prevents directly progressive actions. Therefore, the players defending must move forward in unison to close off effective space, isolate the ball carrier and prevent the opening of undermining passing angles. This is a difficult task to achieve considering the ball-carrier is currently unpressured and is aware of the permutations of misalignment. The area must likely to produce misalignment in this circumstance is the central pressing player responsible for closing the ball carrier (wide players are greater distance as they are not tight to their marker). When he thinks he is within isolating distances and moves to ball-orientation, play a pass to the wide player, a gap now appears in between the lines to find the player at the tip. Therefore, rather than being a forced circumstance via failed transition, this is provoked by Shakhtar when there is a greater distance between the wide midfielders which prevents them from being the players responsible for closing down as it generates more time comparatively for the interior play to turn and progress rather than receive, act as a wall for the onrushing supporting wider player, meaning the opposition last line is exposed earlier, when they have had less time to re-group following the collapse of the mid-block rather than the slower transition from mid-to-low block. The key to exposing this type of man-oriented mid-block is drawing the oppositions midfield forward to generate greater spaces in between the second and third lines, and I think this type of diamond achieves it better than the others.

Should the opposition seek to disrupt the diamond through prioritising coverage of the other players, centre back progression is facilitated to provoke a response and often find the width holder who can then move inwards to the space vacated or find a pass to the player vacated to follow the progressing centre back. Centre back dribbling more holistically is something Shakhtar have used against passive opponents when progression options are cut in an attempt to disrupt marking schemes through players into the orbit of the centre back, creating a free man, or as detailed to find the outlet width holder.

It should be noted moreover that the typical actors are the ball-sided support wider players of the 4, the central pivot and interior, meaning the width holder is free from responsibility, making the potential for a 2v1 overload following breaching a real possibility or if reception comes from wide, rather than centre to receive on the half-turn, the underloaded far-side is exposed. Thus, it shows the theory of the 4-1 coming to fruition, with the consequence of either progression being the creation of 2v1 situations on the flanks where positional play wing dynamics are used to effectively overload the oppositions full back.

One potential issue with Shakhtar is their reliance on this mechanism to create chances, as they have struggled otherwise. Lassina Traoré in contrast to talismanic forward Francesco Caputo offers more potential for hold-up play, allowing for tight interplay in between the lines around the box, having already shown a proclivity for linking play. However, this may be a consequence of the opposition faced, as creating transitional moments from deep has been impossible due to the passivity of opponents. When teams obstinately remain centrally compact, infiltration in behind through going around is often the best option, particularly when your set-up is predicated on achieving wide overloads. Hence upon further reflection there is potential that this ‘issue’ is a feature, rather than a bug with the lack of diversity stemming from optimising around the opponent.

Potential for deeper press-baiting

In reference to questions about lack of comparative possession dominance in the second leg against Genk, but with maintained threat, Roberto de Zerbi responded “…The tougher the pressure, the more vertical further development”.[1] And it is this aspect I shall focus on henceforth, detailing the more transitional style necessitated, and welcomed by higher pressure, analysing the methods used to bypass the opposition to expose uncovered space for attacking transitions.

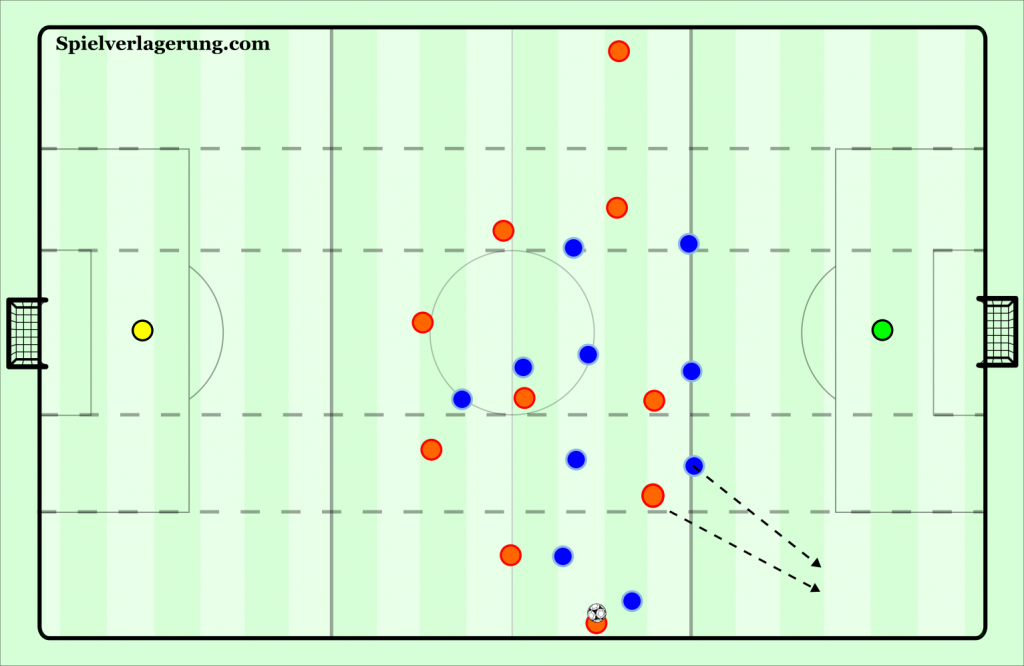

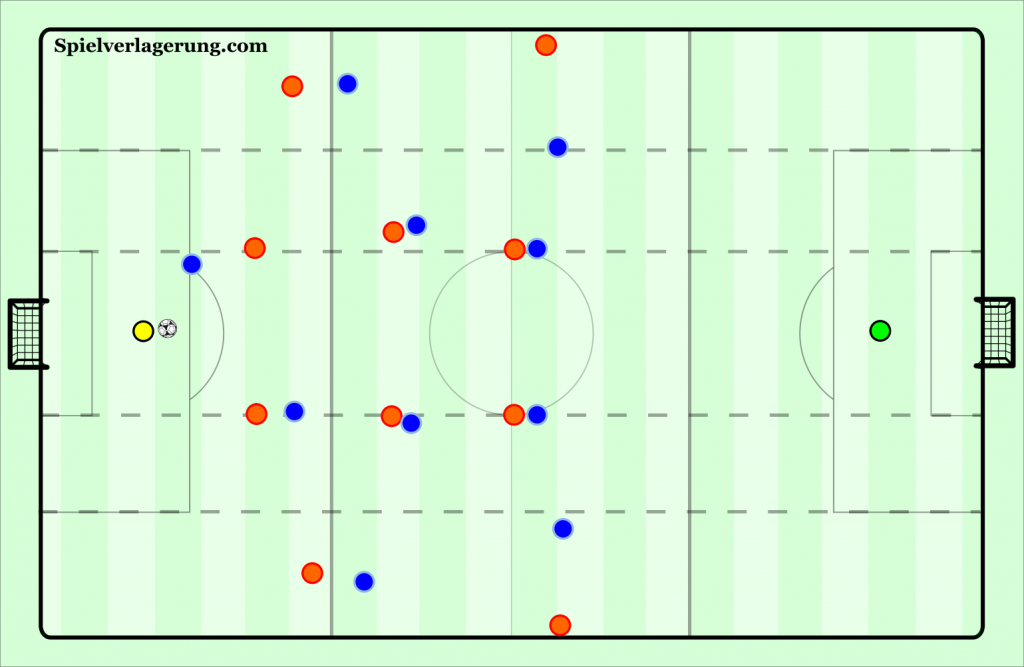

As mentioned previously, Genk in the first fixture used man-oriented marking to attempt to prevent progression; however, in the second leg they were more aggressive (engaged higher and in a more sustained fashion) while using the same scheme which looked to isolate the ball carrier through tightly marking his options while one player presses in a ball-oriented manner, preventing the Shakhtar players from having time in possession or short options, thus removing them from their comfort zone. Because progressive options are cut, and there was a reticence to go aimlessly direct when there is potential to re-group, the backwards pass to the goalkeeper was an option frequently used which allowed them to gain a +1 in possession to better consolidate. From these situations Shakhtar use a 2-4-4 structure (may be referred to as a 4-2-4, but the full backs are generally lateral with the midfielders rather than defenders contrasted to say, Inter Milan under Antiono Conte where the ‘full backs’ were often lateral with the centre backs)– deep wide full backs and a double pivot alongside high wingers.

The goalkeeper can be an extremely influential actor in deep possession sequences, particularly in the first third because they act as a safety net towards recycling possession as their status as a +1 makes it difficult to simultaneously cover all outfield near passing options and the goalkeeper. As play deepens, subtle goalkeeper staggering to open passing lanes while still making them an active player in possession and maintaining strong progressive links is pertinent. A small degree of vertical distancing from centre backs is desired to better open safety passing angles and generate distance from the oppositions pressing players, to get the time in possession necessary to expose the opposition compactness more methodically. They can exploit their central positioning to gain access to the underloaded far-side to provoke a transition, or at the very least alleviate pressure temporarily and allow for consolidation and potentially another switch once the opposition has shuttled.

The theory behind the 2-4-4 is that the there is a desire to horizontally stretch the opponent’s first pressing line to reduce compactness to make central infiltration easier, while when moving backwards, or facing high pressure, there is increased potential for verticality as the opponent must cover a half rather than a reduced playing area generated through the compactness via exploitation of the offside rule. Therefore, as the full backs widen, greater deep central occupation is required from Shakhtars midfielders. This directly links to the vertical development mentioned by de Zerbi, as when building from deep they desire vertical detachment between the 2-4 and 4. This hedges on the riskier side of the vicissitudes of verticality, as it extends the space between the oppositions 2nd and 3rd line, assuming continuation of man-oriented high pressing as exhibited by Genk. This space thereby becomes the exploitable region and generating access becomes paramount.

The deep full back (highlights the symbiotic relationship between horizontal and vertical stretching, particularly against narrow pressing set-ups it allows the team to work around the oppositions lines of pressure through decreasing the opposition compactness vertically (by drawing pressure deep) and consequently opening a passing angle through the sides, reaching extents not covered by the pressing line, creating temporary 2v1 situations against the oppositions wider forward. Essentially, deep build-up has a special transitional quality in that the opponent do not have a degree of control of the vertical playing area, allowing them to be stretched, making link up in between the lines more viable, particularly against man-orientation where the receiving player has the initiative on his marker. Thus, when passing to the full back, vertical access is generated to vertically stretching winger, who being tightly marked, can often only play it backwards, but the space he is playing into is open for contestation, and generally these phases are automatised because the predictability of the situation increases as Shakhtar gain control of proceedings allowing for superior knowledge to be used to connect. Thus, the horizontal stretching of the deeper wide full back opens access to exploit the vertical stretching.

The deep full back is a fundamentally a transitional role because of the ease of opposition constrainment once shuttling has occurred, which is why Shakhtar, for instance do not use it at half-way line possession where play is more compact, making it more difficult to directly transition. However, the goalkeeper is pertinent here as the depth of play allows for his integration. Because of the staggering principles to add an extra layer of depth establish a link between the horizontally stretched size, the wide playing area is made more effective due to the presence of a free central actor which is difficult to achieve elsewhere; ergo, this is the primary reason wide full backs are more effective deeper, they have an additional options and therefore reduced chance of constrainment will increasing ball-sidedness (the other main benefit is the 2nd and 3rd line IBTL space). This means ball-sided pressure is drawn to limit options, whilst vertically they have committed to at least the penalty box meaning space is exposed in behind, where exploitation of an otherwise unavailable option (goalkeeper) is possible to transform what would in other regions of the pitch be a sure-fire turnover/throw-in, into a transitional opportunity as the far-side is exposed.

The technique often used centrally to progress is to drop one or two of the forward sitting players who generally occupy half-spaces. This provides a direct pass to breach the pressure, unless as is typical, they are followed by their corresponding centre back who closes off angles for progression via his tight marking, forcing play backwards unless a risky turn is attempted when the team is horizontally and vertically stretched and thus not suited for a defensive transition (hence amplifying risk). Shakhtar conceded in the first leg in such circumstances, as the conditions conducive to ball progression attempted to be manufactured can be instantly reversed to a turnover, hence, the vicissitudes of verticality.

Against Zorya however, the benefits of this approach were clear to see as the dropping forwards, namely Pedrinho used his dynamic superiority to win the first ball, then the qualitative to turn away, typically finding the near-side winger high and wide who can now progress or attempt to exploit the space left by the dropping centre back – which is a necessary feature of the type of man-oriented pressing adopted. Another alternative was the dynamic superiority 1-2 where one forward centralises and drops, flicks it on to the other forward who uses his teammates reception as a trigger, to subsequently play it back into the space for him to receive after rotating and find the near-side winger. Additionally, as with this discussion holistically, detailing all permutations is extraordinarily difficult due to the various opposition responses and spontaneous action undertaken in possession to adapt around unavoidable novelty, as one could also imagine an up-back through sequence originating from this with a penetrative winger if a deeper midfield passing option was open, for example. It depends on how the defender pressures, which space they leave open when attempting to regain possession (do they seek to funnel out wide with a centrally cutting tackle etc.).

The importance of the full back positioning to open these passing angles cannot be understated, as the horizontal stretching makes the CB far more capable of finding the pass if the wide full back is covered, with the opponents opting for first line spatial coverage over compactness, potentially aware of the symbiotic relationship mentioned, meaning the forward receiving is more isolated in a duelling circumstance, with the opponent being unable to compact centrally quickly. Similar notions of the qualitative superiority can be used here as players such as Pedrinho thrive under such circumstances where they need to use their acceleration, agility, and tight dribbling abilities to escape a marker and expose the forward pressing commitment.

The wingers remain high and wide to firstly grant access to the up-back pass to infiltrate in between the lines, but secondly to act as a more direct threat as if unfollowed by their marker, they can generally craft more space for themselves to receive directly to alleviate pressure, or if followed tightly they serve to decrease opposition compactness which creates infiltratable space for a through ball if possible, or more feasibly, a pass into the interior player via the full back, who from there has the options of going backwards or attempting a duel. Another potential sequence in conjunction with the deepening forward, is that he draws his marker, the centre back, who leaves vital space unoccupied. The winger can move into this space to access a through ball once the deep player has played it forward (possibly a goalkeeper launch), using his initially wide positioning to manipulate the opposition into leaving the space unoccupied only to invade it. Otherwise, the alternative is the oppositions full back is informed to compact once the centre back follows the midfielder, which then allows the winger a better chance of receiving possession directly if they stay out wide. During central progression, the wingers moreover often function as a (up-back and) through option as the full back compacts, with their width similarly allowing for more assured possession reception or otherwise a less compact defence where central infiltration looms, making the wide progression variant more common. Furthermore, they remain wide even when the ball is on their far-side, continuing to be an option for the direct ball as to be instantly dangerous and in an opportune positioning to receive from the central link to fully capitalise upon the opponent’s ball sidedness. An example of this occurred in the 60th minute of the first fixture against Genk, where a more direct ball was played after deep full back possession and opposition ball sided commitment was nullified by a central pass into a direct switch to the winger, who then had complementary movement from his full back, which allowed central access, eventually creating Pedrinho’s duel to win the penalty.

Additionally, there be a degree of control achieved from this depth, particularly around the box where the opponent is more reticent to press, knowing they are reaching their vertical limits and that space in between the lines will become increasingly difficult to compensate for and they are facing an opposition capable of consistently generating a free man due to the +1. Thus, seeing goalkeeper central passes to the double pivot, who instantly under pressure may play it backwards, for possession to be recycled to the centre back, then to the keeper again is not an unsurprising circumstance, as Shakhtar look to bait the opponent forward to generate the free man in higher regions. The progression generally attempted is that to the dropping forward(s), with the near-side double pivot potentially narrowing his positioning to open the vertical passing lane, drawing his marker with, to potentially evade and link up in between the lines afterwards. Here is where the dynamic superiority becomes pertinent as initiative must be used to receive possession ahead of their marker. Linking back towards a previous topic, the finding of the far-side CB often becomes pertinent here to open the passing angle by drawing an element of opposition ball-sidedness.

When progress has happened to the forward player because the opposition forward pressing the far-side (now near) is responsible for two players, keeping the midfielder in his cover shadow and pressing the centre back, the centremost midfielder now becomes temporarily accessible as a passing option, as the opponent looks to shuttle to cover the ball-side options.

If the forward player embraces the vicissitudes of verticality and attempts to beat his marker in a duel, he typically progresses into the spaces in between the lines then seeks the high and wide winger posing a threat on the last line while being a viable option for reception, who typically then receives complementary movement from an onrushing full back.

Moreover, use of the symbiotic relationship of horizontal and vertical stretching to find an inwards diagonal pass to the far-side midfielder is used to infiltrate centrally. A passing triangle is formed between the centre back, full back and near-side midfielder who are marked tightly by the opponent, who has committed to ball-sided pressure. The near-side midfielder will come deep to provide a short passing option; however, pertinently, he also manipulates the positioning of his man-oriented marker, who following rigidly is no longer covering the diagonal passing lane accessible due to increased space in between the lines, opening access to the far-side but central (remember the pattern which is consistent in the near-side pivot offers short support to the ball carrier or drops with the far-side pivot centralising) midfielder to receive, even if followed diligently by a forward, who will be oriented on the wrong side for this particular type of reception. However, also common is to leave the forward higher, thinking the cover shadow is sufficient meaning the midfielder is free to receive. If free, looking to change the direction of play through linking to the half-space forward, then to the winger is optimal to reach extents underloaded by the opposition to best exploit uncovered space, and newly introduced space created via the offensive transition. A heuristic for the opposition to follow to potentially avoid this is do not follow Shakhtar’s midfielders when they are constrained to the ball-side and lateral to the full back, rather attempt to maintain an effective distance to close down while bearing in mind passing lanes. But this solution is susceptible to the finding the far-side CB solution as the midfielder will be able to receive in a backwards orientation, and the far-side forward will have to cover the newly opened passing lane to the midfielder, which then presents potentials for central progression via forwards detailed.

A back 4(+1 goalkeeper) recycling routine to find the midfielders can be envisaged where the opposition playing a ball-sided man-oriented 4-4-2 where the near-side forward must close the near-side centre back and limit options out-wide or meaning the pass the goalkeeper is opened, which is followed by the near-side forward, when possession is then circulated to the far-side centre back, which engages the far-side forward in pressing, while the midfielder (near-side, was the central during previous period) is now uncovered because in the pressing scheme he is responsible for the pivot or far-side midfielder in Shakhtar’s case. Shakhtar’s near-side forward player has dropped sufficiently deep to be relinquished by the centre back and bequeathed to a midfielder, who can perform an up-back sequence to find to the central midfielder. From there, permutations become vary; however, potential includes the other forward drops to support, whilst the previously mentioned forward engages in a third man-run to access the space in behind his marker, who has potentially changed to ball orientation in response to the midfielder getting the ball free – passes can then be played towards the winger.

Another possibility from goalkeeper centre back circulation is accessing the near-side midfielder through the full back. If the opponent commits to pressing the keeper, the player previously responsible for the near-side centre back will jump on the centre back while maintaining the midfielder in his cover shadow. However, through going around, the cover shadow will be circumvented allowing an inwards pass with reception angled towards the centre. In the 55th minute against Genk in the first fixture, something even more adventurous was possible in similar circumstances due to the lack of pressing intensity of their forward, where the space in between the pressing lines from centre back to midfielder was large because of the efficacy of goalkeeper staggering should it be followed, resulting in an easy inwards pass to bypass pressure, then to his midfield partner.

Lastly, I should note the goal kick structure is similar although more rigid due to the static nature of play from these situations. However, the underlying theory and methods remain similar, just perhaps more difficult to execute because the opponent are better structured. The aim is to compact, create detachment and use the vacant space in between the 2nd and 3rd lines to transition into and expose the opposition last line while using the width of the wingers to make too difficult to defend.

Throughout all of this however, it is important to remember the spontaneity and unpredictability of circumstances depend on in-game situations, which makes these sequences, once in action difficult to automatise. Therefore, while these sequences can be categorised as near-side midfielder via deep full back going around for instance, they are functioning under principles rather than being something consciously pre-determined action by action. Nonetheless some actions still imply others. This type of principled play relies on more abstract concepts such as how to support the ball carrier, how to escape cover shadows and manipulate opposition positioning to open passing lanes to teammates on an individual level in addition to macro level concepts such as the deep full back maximally stretching the first line of the press and deeper build-up facilitating a greater degree vertically though removing the tool of offside. These broader concepts are more important than the atomised sequences which display them. Understanding the abstract is crucial in the repetition of patterns (unless very predictable circumstances are created, such as the up-back and through which is repeatable after the trigger of centre back to forward, signalling a midfielder third man run in between the lines). Memory and time are finite, and football can be unpredictable; therefore, attempting to consciously direct every action of variable play is an impossible task. Concepts are higher-level than actions because they are adaptable and create actions. I think it is the principles coached and shapes used which make de Zerbi’s teams so effective. It rests somewhere between Antonio Conte or Simone Inzaghi level of automatisation and the desire to create predictable sequences to automatise and individual discretion given to players. There are certain items in the playbook, and checklists to go through i.e., finding the underloaded centre back goes through defensive midfielder, then narrowing full back, then dropping interior (which links to the half-space diamond concept) but these are adaptable in interpretation because they are flexible concepts which allows for improvisation within tight spaces to escape pressure and adaptation around various types of pressure. In essence, because of the way Shakhtar play, which functions fundamentally under the positional play mantra of ‘moving the opponent’, a diversity of potentialities open because of the variety of responses both from differing opponents and within matches as players defending react differently in every circumstance, sometimes not tracking with the same degree of intensity, or following a player on one occasion to compensate for a lost duel opening space etc., which may allow for a pass in between the lines to an interior, which is sometimes closed off due to greater opposition compactness where typically the slower, and less transitional route of going around the compactness to the full back is better, and perhaps the one trained for more frequently in an automatised manner because it is a more difficult situation to create a chance out of. Essentially, what makes Shakhtar, accompanied by de Zerbi’s Sassuolo so impressive in build-up is the ability to find a solution, and work (thrive) in difficult circumstances because the players know how to receive and create in tight spaces, and are encouraged to take risks. Meaning they use their shape, and the more abstract elements (far-side double pivot player moves into central pivot area as the far-side pivot supports ball carrier or acts as a third CB) to craft particular situations, or groupings of players in deep areas and transition subsequently.

To conclude, hopefully this article has presented many of the crucial concepts of de Zerbi’s system in addition to how they may manifest in a game, and acts as encouragement to potentially watch Shakhtar, to gain first-hand experience of how his interesting and effective ideas unfold.

Written by Jack McCormack

[1] Roberto De Zerbi: “We need to progress – we work on that” (shakhtar.com)

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen