How Guardiola & 3-2-2-3 (ultimately) solved the defending meta

Guardiola’s image in the football world is complex to describe. While polarizing, everyone seems at least to agree that he is an unique innovator. Funnily enough, he is polarizing exactly because of this mutual agreement of critics and fans. The public discourse about his Barcelona team mainly revolved about the positional style of play and – even contrasted with Aragones’ successful EURO campaign with the Spanish national team – was highly focused on his idea of playing football and how it differed from most teams. Building up from the back with passes on the ground and involvement of the goalkeeper even under pressure, overload in the center while maintaining high width and depth, or even their extreme pressure with an extraordinarily high line to enable early regain of possession have conquered football back then (with two Champions League titles in four heavily favored campaigns) and since taken over the ideas of others teams more and more – some of them, Guardiola had started already in his first year as head coach back at Barcelona B.

Whilst Guardiola has stayed on the forefront at the evolution of his revolution, his advantage over fellow managers seemingly decreased step by step in the meantime. At times, Guardiola received criticism for being either too eager to increase this gap again or his competitors seemed to value other, obviously important aspects more or more accurately than him – i.e. counters.

Immortality without Invincibility

In his last season at Barcelona, the quality of his team and himself, admittedly, looked superior to anyone in Europe. Yet, his focus on constant improvement seemed to change his team from invincible to beatable, at times. Experiments with a back three led to higher peak games which were less sustained than perhaps the 2010-11 version of Guardiola’s Barcelona. His personal improvement led to more and more details, but those also looked like limiters to an unlimited team that was based on the core of Messi, Iniesta, Xavi and Busquets. This, allegedly, reflected itself in the locker room and with the board. This only tells half of the truth. Although Guardiola status as untouchable in the media changed from year one to year four at Barcelona, he did change less than it was written about him.

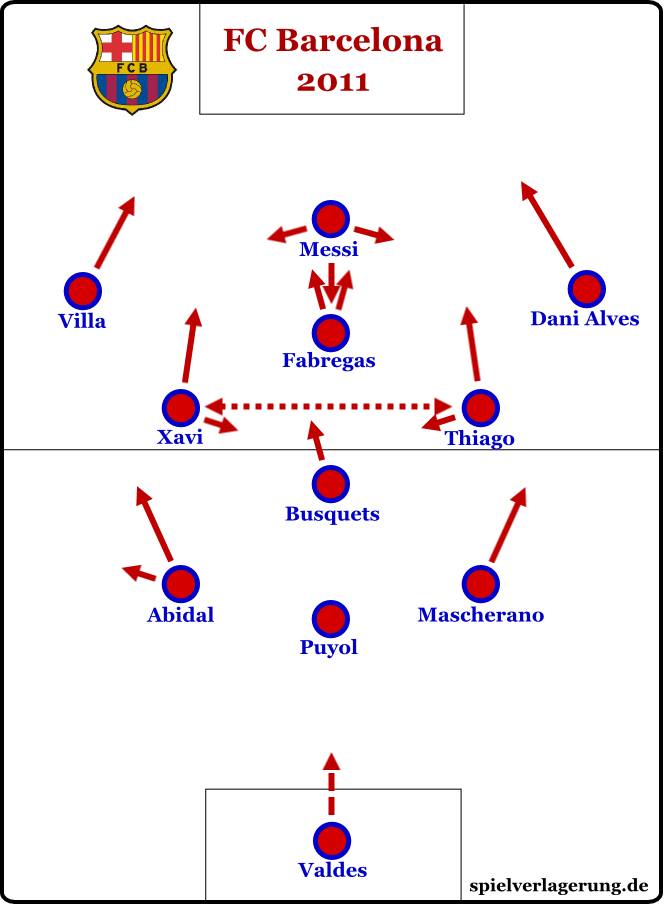

The main reason being a lack of attention on details and lack of quality in the discourse at the start of the Guardiola era. At Barcelona’s legendary 6-2 win against Real Madrid, the so-called false Nine was exactly the kind of tinkering that would have received backlash a few years later in games lost or drawn. The perhaps even more legendary 5-0 two years later involved a back three build up with Abidal staying deeper, a box-midfield in the center (with Xavi and Busquets at its base, behind Messi and Iniesta) and an asymmetry in the last line with Villa, Pedro and Dani Alves (which bores a heavy similarity to his Manchester City 2021).

Narratives, after all, are written by results, just like history is written by winners. Guardiola’s perfect record from his first season was obviously unattainable, yet the media started to prepare a fall from a height yet undefined and unknown for previous managers.

The Man Who Could Only Beat Himself

Obviously, Guardiola was not fazed too much by this criticism from outsiders and literally within the first few weeks of his sabbatical, he seemed the most sought-after person in the football business for the next season. Despite his tenure at Bayern Munich not quite fulfilling desires and expectations, at many, many times, absolutely brilliant football and highly successful domestic campaigns was played. It was the lack of ultimate success in the Champions League with the Heynckes’ treble winners that seemed finally to lessen Guardiola’s image internationally a tad. And still, his principles were not only constantly visible but in constant change at the same time while he worked in Germany.

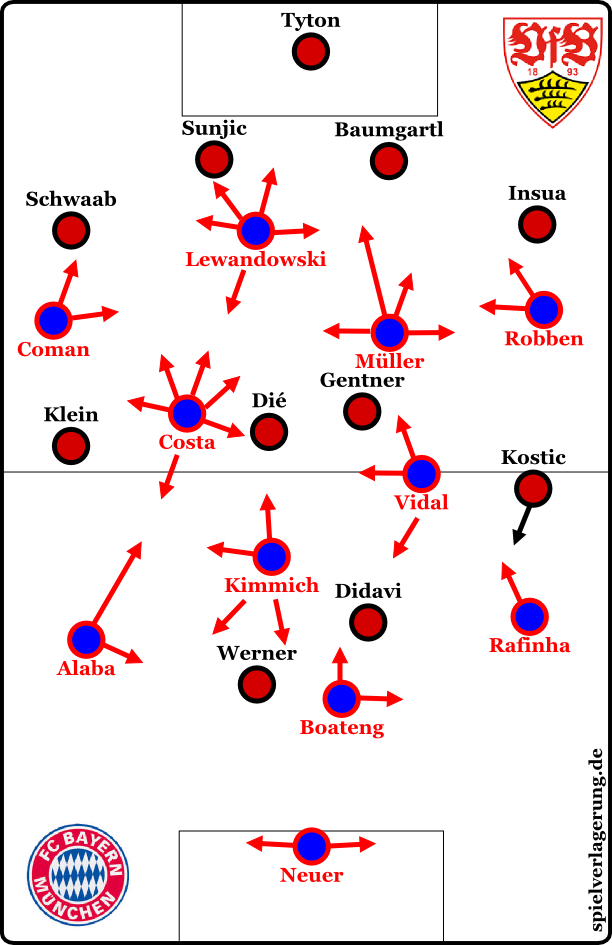

Structural changes and personnel rotation from game to game and within an individual game became much more frequent than at Barcelona. Without the any-oppositional-matchplan-withstanding quality of Messi, Iniesta, Xavi and also Busquets, the need of his managerial impact seemed to grow even bigger. This Bayern team, despite their success before Pep, needed his (additional) ideas to not only stay on top, but also to improve on it in their peak moments and to change to and play his style on the level they ought to. Without Messi to overload the center and in a pressing-and-counter-heavy league, Guardiola turned to Lahm and Alaba, his full backs, among others to enable his principles successfully.

With even occasional games with a diamond consisting of Ribéry, Robben, Götze and Alonso happened as some adaptation to Guardiola’s style regarding transitional play and the value of possession, all these various line-ups and systems consistently looked more direct than Guardiola’s Barcelona did at least at its last two seasons.

In Bayern Munich, Guardiola has promoted the Positional Play that Louis van Gaal introduced five years ago. But the one Bayern is practicing right now is a game that is much more oriented to a vertical axis than a horizontal one and this version requires a high degree of technical excellence because it seeks to construct the above mentioned superiorities not based on horizontal but vertical passes. This is an extremely ambitious interpretation of Positional Play.” – Marti Perarnau

While it was still immediately recognizable as a Guardiola team, a different flexibility not only tactically, but also strategically arose. The lack of the ultimate Champions League success combined with Guardiola’s adaptations lead to a change in his image in the media: From an unbeatable coach to a potentially unbeatable coach whose tinkering and thinking more often than not led to him beating himself on the highest level without Barcelona’s top stars. Still, even then this was a narrative in the media and hardly in the business. Within the football bubble, Guardiola’s image stayed the same and Manchester City tried everything to lure him away from Munich.

A Counter Part To Beat Him

Fast forward another three years and Guardiola’s image has changed a lot. Despite, again, (“only”) domestically successful campaigns with the Citizens, the narrative became worse ever-so-slowly. Now it was not only written that Guardiola was beating himself, he got called “figured out” – mainly by Jürgen Klopp, who’s enthusiastic approach to leadership and playing style finally seemed to be a proper counterpart to Guardiola and to take over the crown of the world’s best football manager. Besides a much higher focus on positional play than at his time in Dortmund, it looked like counters, a certain physicality in their pressing approach and various type of set-pieces looked like an industrial brute-force solution to Guardiola’s style. At times this narrative seemed so simple that it had to be true. His duels with Klopp already in Germany with Dortmund but even-more-so with Liverpool later on seemed to force Guardiola towards unusual adaptations, even for him, by moving him from his principles partly or punishing them with losses.

Even a 100-point-campaign only seemed to prolong for the inevitable criticism of too long and thus inefficient possession, too naïve and widely staggered positions in rest-defense, the disadvantages of trading off traditional defending qualities at center and full backs, or even a superficial lack of physicality. Patiently defending and then winning the ball for fast counters, never mind how long it took at times, were called enough to get on par with City. Basically, the equation was clear: If City has long possession, both teams have similar, but little scoring chances. If City tries to have shorter spells, they would at times show their peak form and at times concede too many chances to survive the game on the bigger stages / against better opposition.

Compared to Klopp and the “complete Liverpool” from last season’s campaign, Guardiola was made to look stagnant in his playing style, unresponsive to changes reality was seemingly forcing him to acknowledge, regarding not only his ideas of the game, but also himself. Albeit no one ever seemed to ask Liverpool to update their style, Klopp looked like he had even won the battle when Liverpool put opposition into the torture chamber in every phase of play. Guardiola on the other hand found himself at twelfth place after nearly a third of this season.

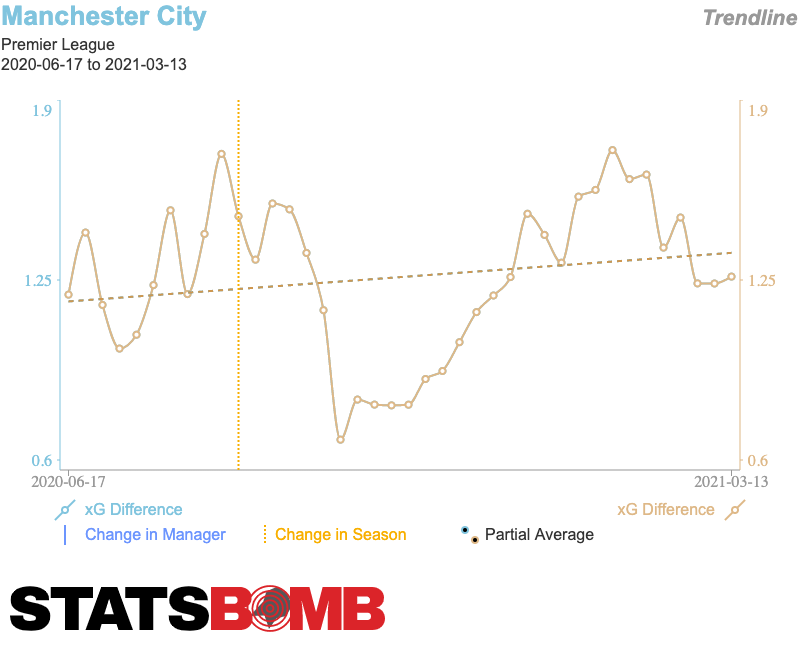

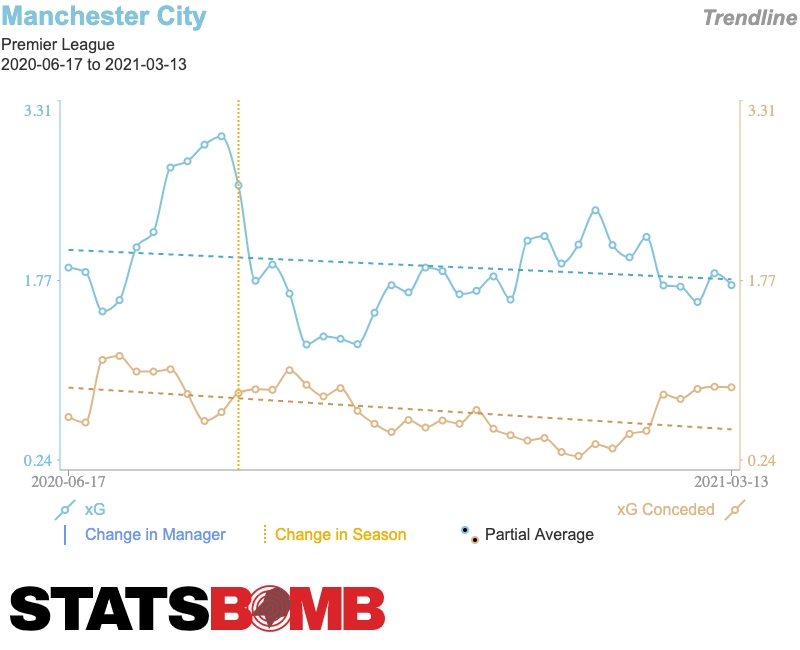

Fast forward a few months and the process is reversed: While Klopp himself is struggling this season (after getting Liverpool their first league title since who-even-knows-anymore) and has to battle for a top four finish, Manchester City have soared through the ranks and look not only the heavy favorite to win the league, but all the other competitions as well. The Catalan manager has attributed this to, among other factors, to a different focus, more closeness and togetherness within the group, even “better sleep”. On the pitch it looks like there might be another reason or two for this, though.

Guardiola’s Latest Solution Is Updating Himself

Although most statistics do not point to any big change – not even last season, where many metrics had put City firmly in front of Liverpool –, the results and the avid watcher will talk about the game against Southampton, just as Guardiola does. Since then, Guardiola’s team has won every single game. What has changed? You could argue, if you want to take the narrative to its own storyline’s end while keeping at least some logic and sanity in your argument, that Guardiola’s tinkering and overthinking has finally led to an end product.

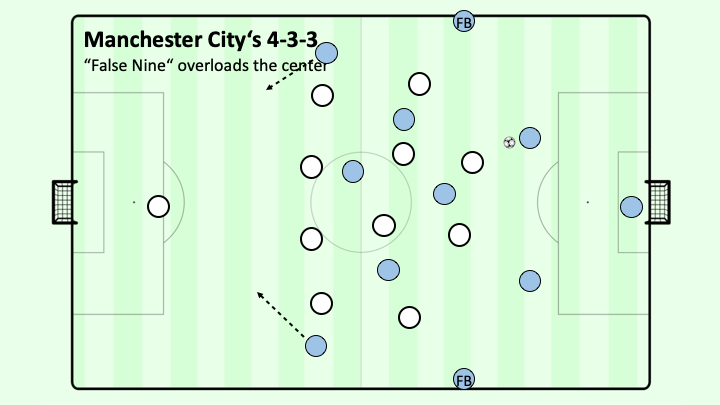

At the start of the season, a 4-1-2-3 with different patterns and line-ups, obviously specified to the opposition, was used fairly regularly. De Bruyne would masquerade as 9 or 8, among other fairly typical adaptations by Guardiola.

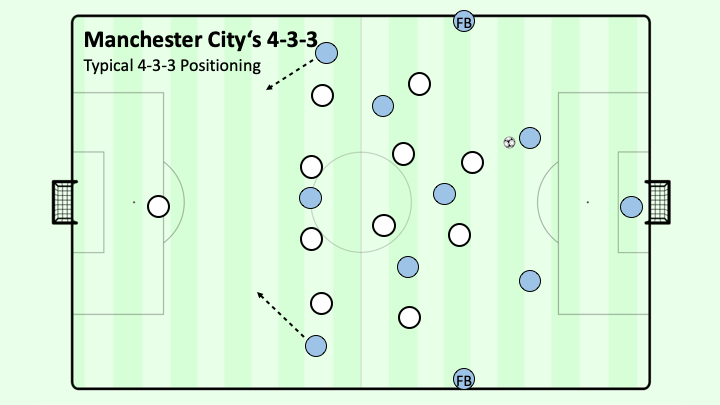

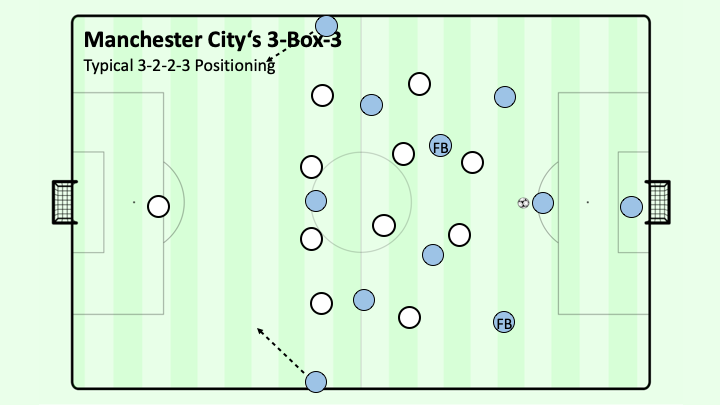

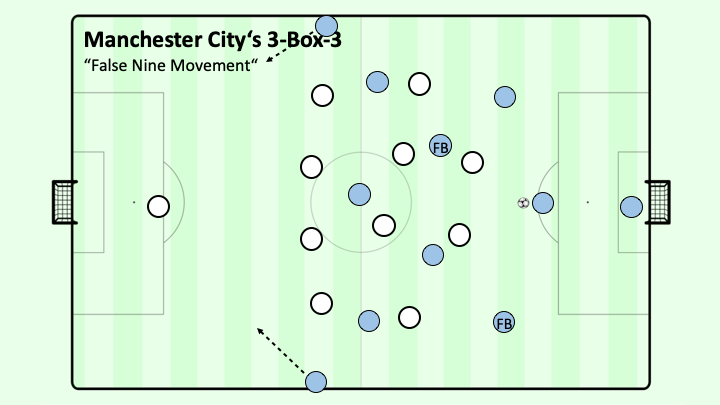

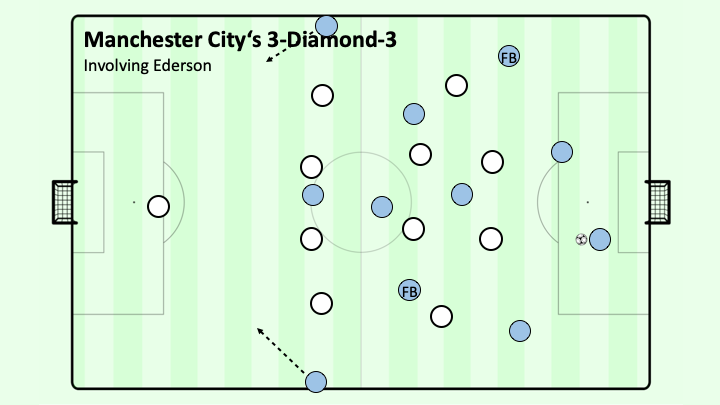

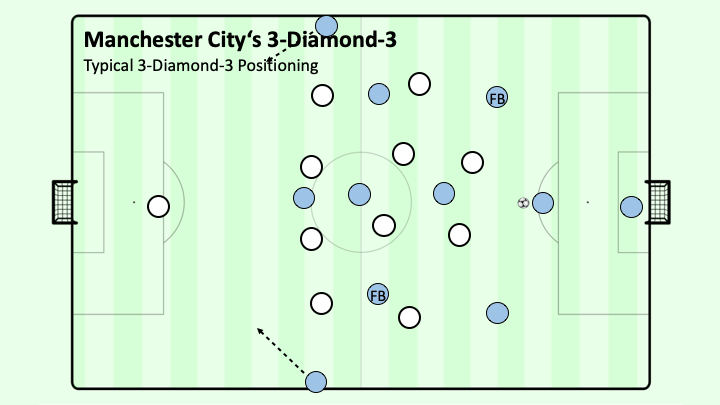

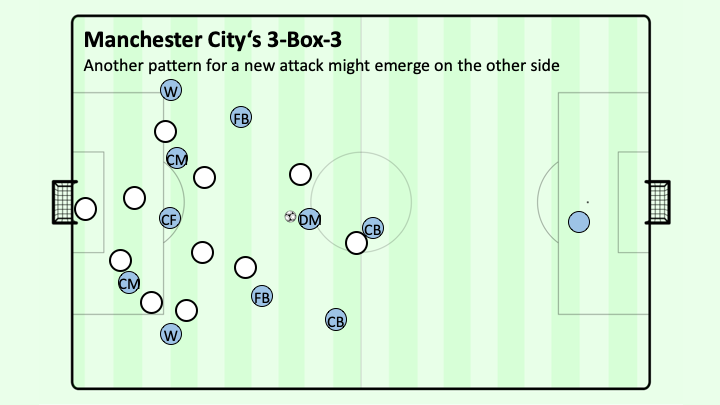

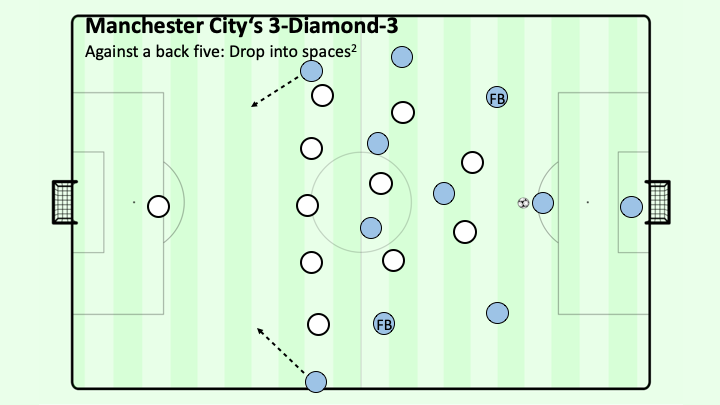

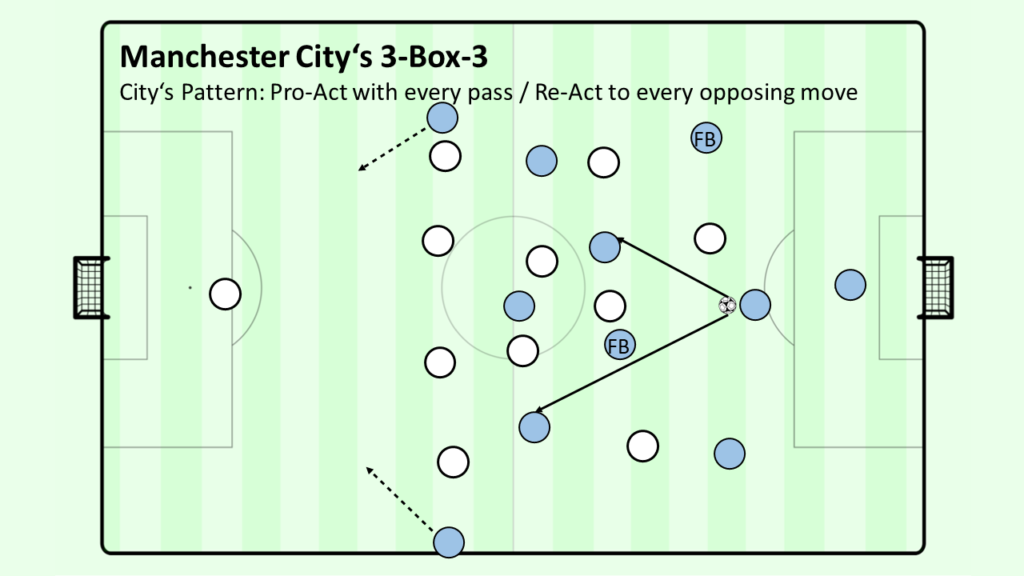

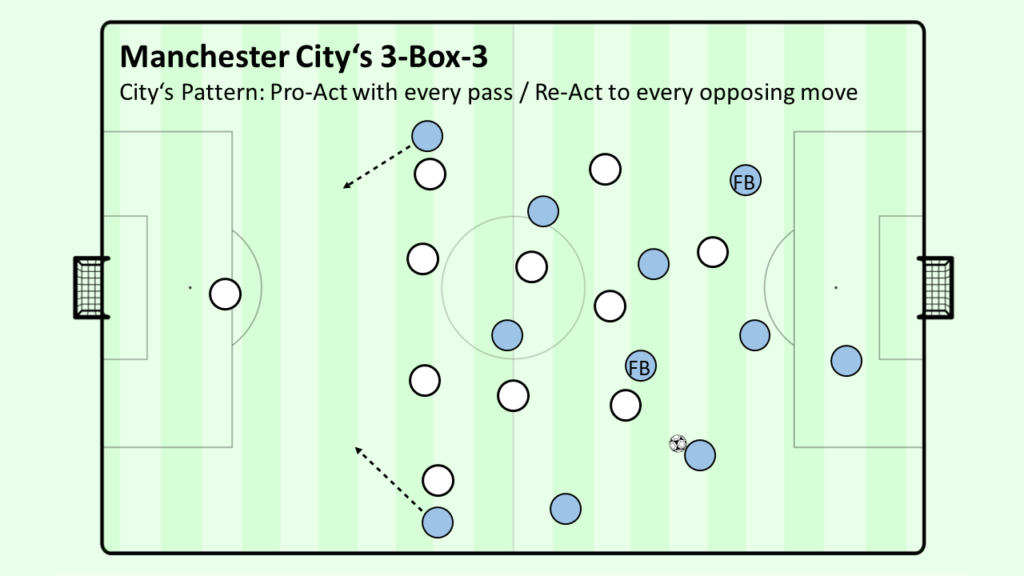

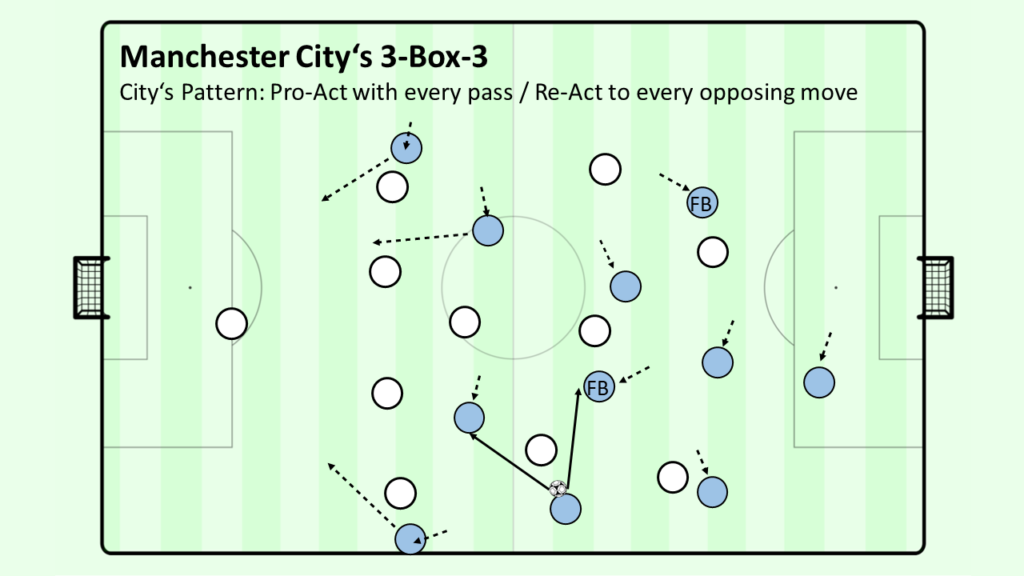

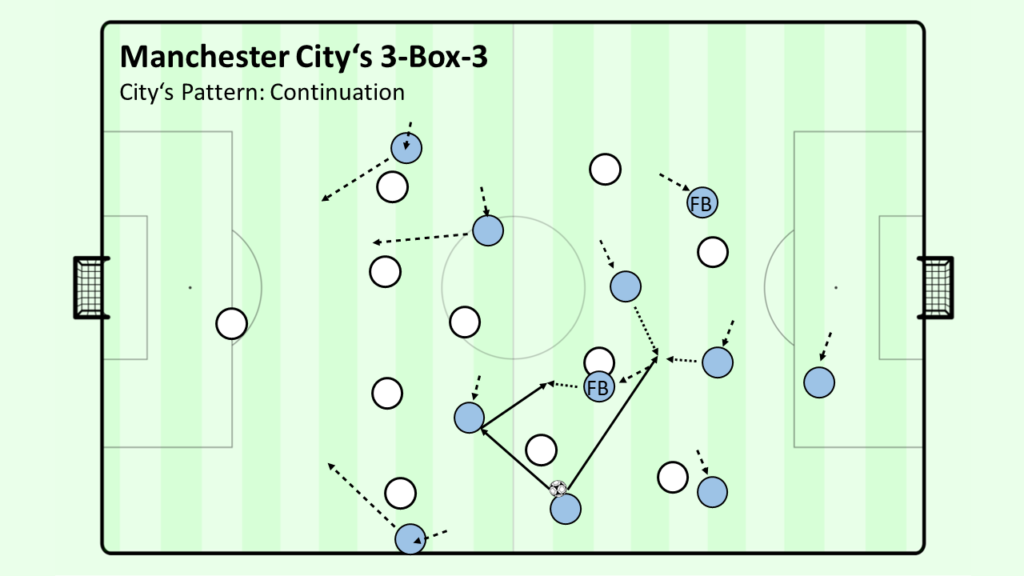

In the last weeks, a different pattern emerged. Like his mentor and former coach, Johan Cruijff, Guardiola started to use a 3-Diamond-3 system for his team. Like in the 5-0 against Real Madrid, it could also be called a 3-2-2-3. The problem for the opposition lies in this very small, yet meaningful (possibility of a) switch.

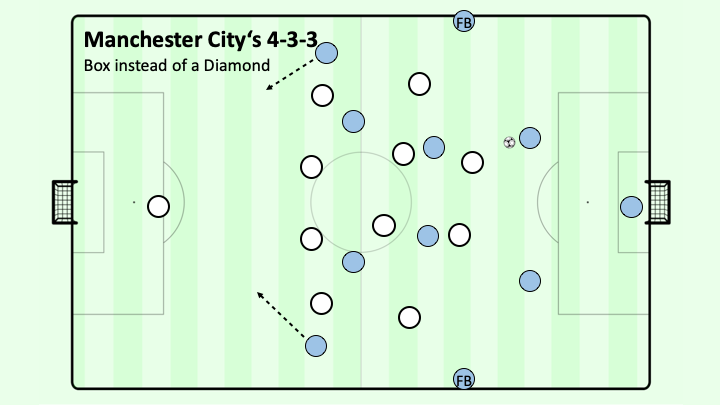

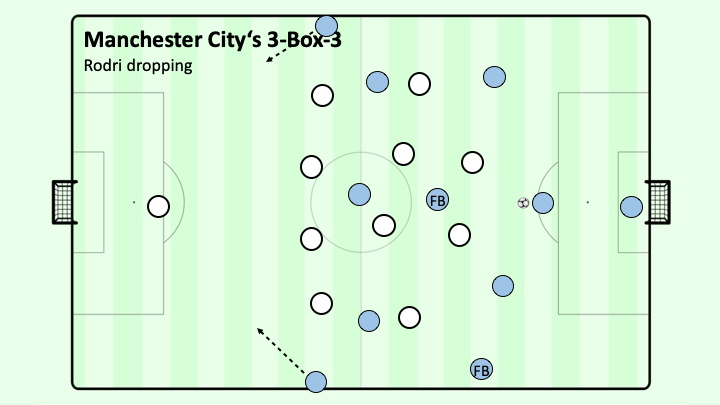

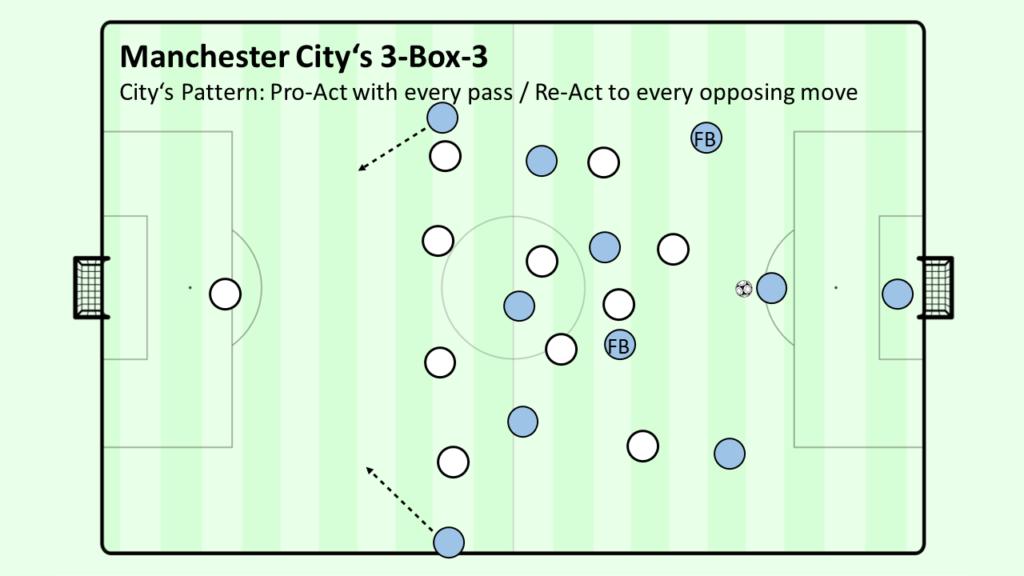

Cancelo or Zinchenko have taken over the role of a second pivot besides Rodri or, rarely, as third attacking midfielder. Guardiola mostly opts for a box midfield where Rodri can drop to the left side and Walker on the right or Laporte on the left as auxiliary centre backs push higher up from their deeper positions while Cancelo still is available in front of the defense as passing option.

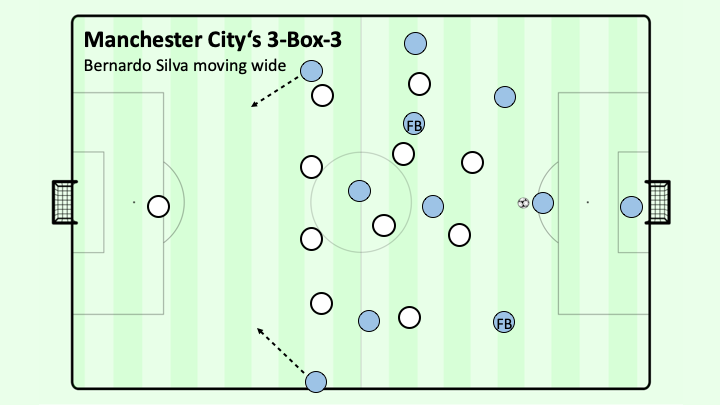

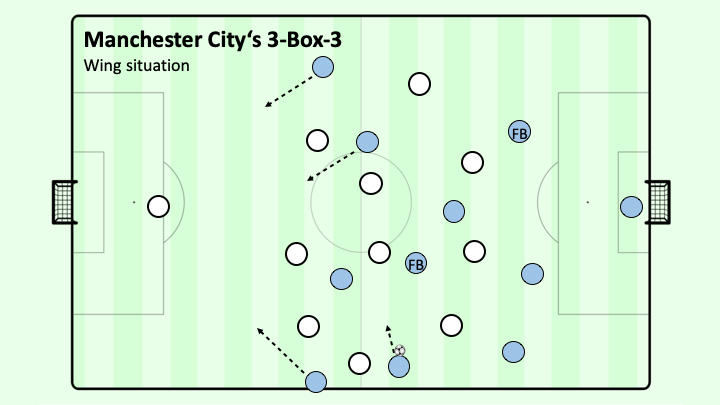

Against different opposition, a diamond might help in giving more passing options between the lines, adds depth to the game, positions a player between every gap of the opposing midfield and just one pivot is enough. This is used very rarely though and is more a pattern within their circulation. If there is higher pressure or a closed, compact center, there is the possibility of moving out wide for Gündogan or Bernardo Silva to create a similar build up pattern like Rodri’s dropping.

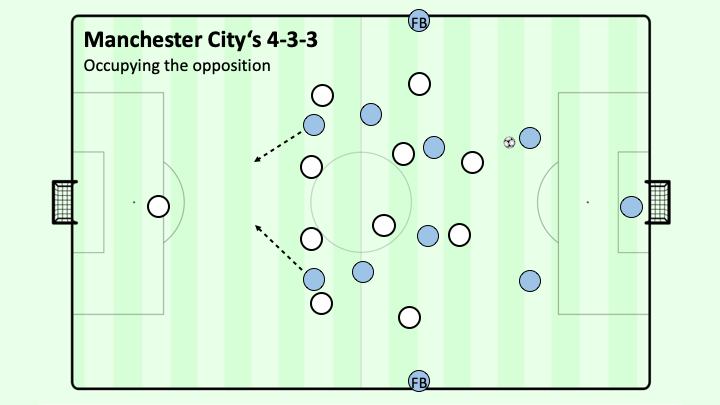

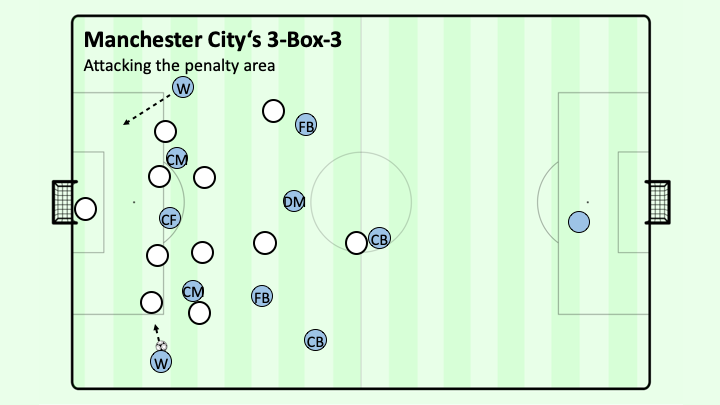

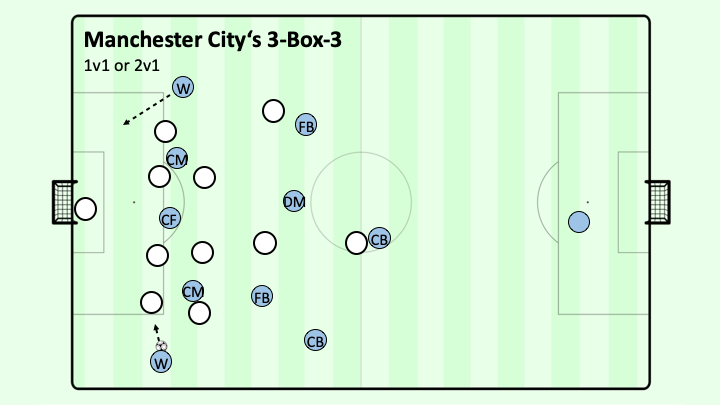

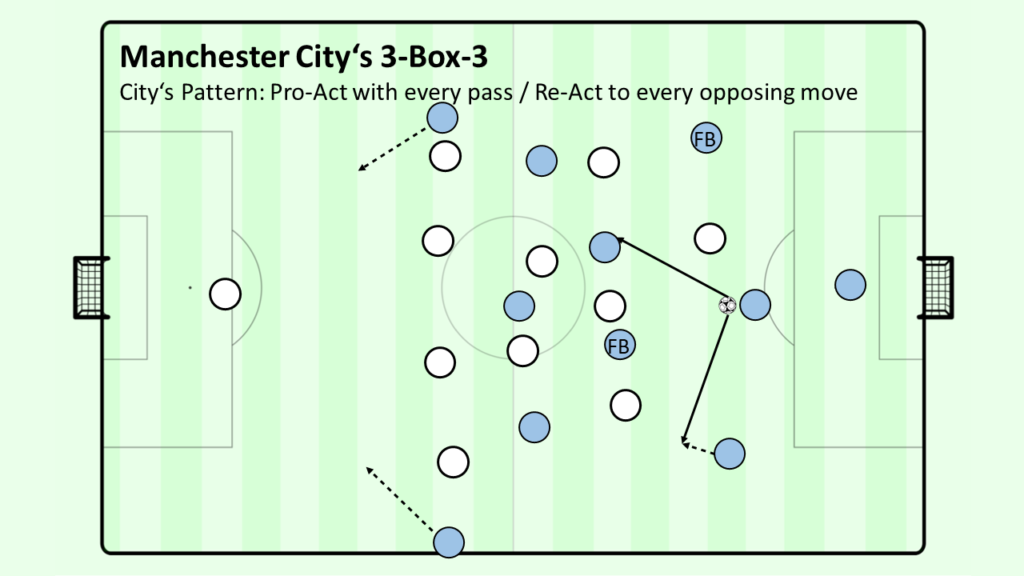

The secret lies in the enormous width they create, though. Whether they play box or diamond in the center of the pitch, opponents always face a three build up and two very high, wide wingers who give depth in behind, fixate the oppositional last line and can solve 1v1-situations. Additionally, Gündogan, Silva or de Bruyne move out to the side and are either a free man, open the center or can combine with numerical superiority on the sides with the wingers. The occasional overlap by the auxiliary center backs does not make it easier for the opposition. To support this movement out wide by the midfielders, City plays not only a box midfield, but also with a center forward to drop additionally and fill the gap in the middle, luring out the center backs with wingers and midfielders threatening with runs in behind and the center forward overloading the center by creating a pentagon, so to say.

This means five players in the middle but with more width than usual and four of them to drop deep or wide to create a solution against more intense pressing of the opposition. Still, the role of their wingers is key: Two players who are ready to go 1 against 1 or run deep behind the defense to open space or punish the closing of space in the center, at times even passed to by goalkeeper Ederson. Add the occasional rotations from midfielders, wingers and center forward to it and it looks not just hard to solve, but fairly unmanageable to execute a solution accurately.

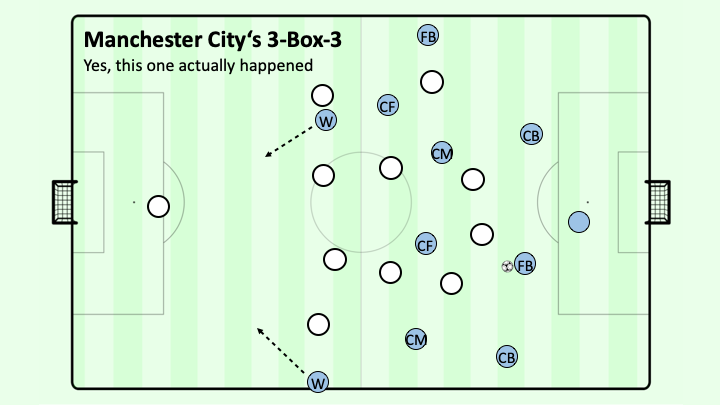

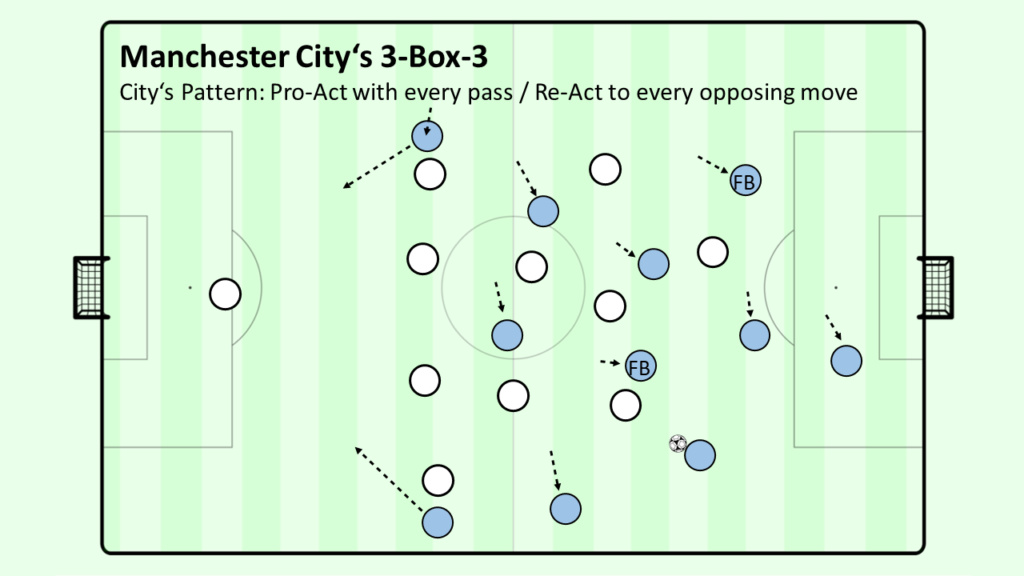

Variations from game to game do still exist. Against Fulham a wholly different approach was used against their man marking scheme, combatting Southampton’s approach the role of the full backs and wingers changed asymmetrically and in the second leg against Gladbach it was Cancelo dropping between the center backs and the false nine at time coming lower than both central midfielders to mess with the oppositional shape. The most fascinating aspect: Bar Fulham, most of these changes are not only created from the same basic structure, but feel quite natural and simple for Manchester City.

This 3-2-2-3 idea with it’s different patterns and heavily coached details looks a personal culmination of all of Guardiola’s principles: Width and depth at the same time in the last line, width in the first line of build-up, flexible overloads in the middle and on the sides, whilst in the same time being able to protect weaknesses that arose from similar structures before through the unique use of full backs and, obviously, the player profiles.

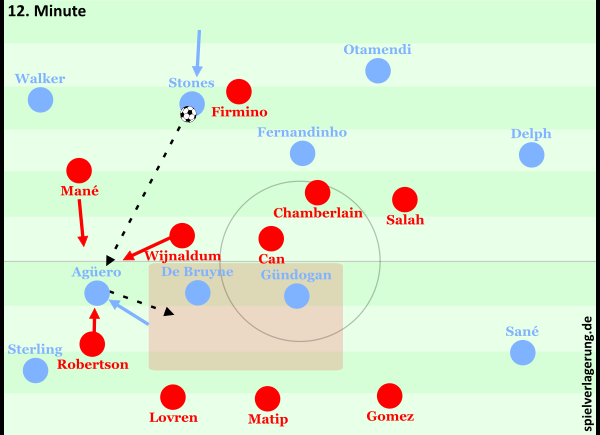

Guardiola’s idea of football is not only about different types of superiorities, as it’s mentioned often in coaching courses or “keeping the ball”, if you want to go as superficial as possible in its explanation. It is about taking away tasks and functions from the defending team with the advantage going to the attacking team. Against a False Nine, the centerbacks and now even the full backs would lose function due to being occupied by the two wingers. The 4-2-2 or 4-Diamond that emerged in the first three lines of Barcelona’s build up would often face – thanks to the goalkeeper – just a 9 against 6 situation with the wide2 finalizing the scheme.

High pressing would stretch the opposition too far out from each other to take away space and time from Guardiola’s men effectively. Deep pressing would lead to the inevitable loss, bar some very hard-earned draws or lucky wins. A medium press (see Klopp, Jürgen) seemed to partially give a solution and fighting chance with Liverpool’s pressing being among the best in football’s history. Now, even these solutions look improbable for luck-independent success against Guardiola’s updated expression of the principles he always had.

The Latest Solution Might Be The Last One

Guardiola’s back three and his wingers have given him the chance to add another player in the heart of the opposing formation or flexibly get one outside to relieve pressure or attract pressure in a controlled manner. Obviously, a lot is down to the players at his disposal. Ederson is as unique as is Cancelo, even if neither are as good as Kevin De Bruyne can be, Sterling’s skillset potentially the most valuable for Champions League success and the Dias and Stones partnership, perhaps, the most important aspect of their circulation.

But not only individual ideas and players of opposition have lost defending functions against Guardiola’s system and Manchester City’s individual and collective quality, there seems to be more at stake. Classical defending looks outlived and solved. Guardiola’s latest update has prevented him not only from dying down from his bugs, as it seemed before the patch at the start of the season, it has created the potential to solve any problem the defending team poses from the same basic structure, if executed well enough. Yet, it is the truth.

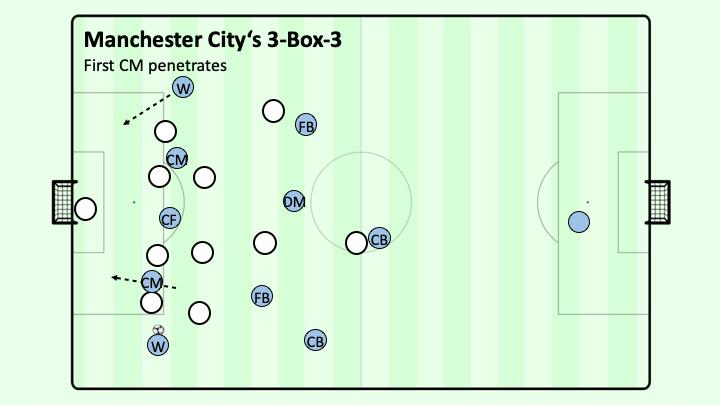

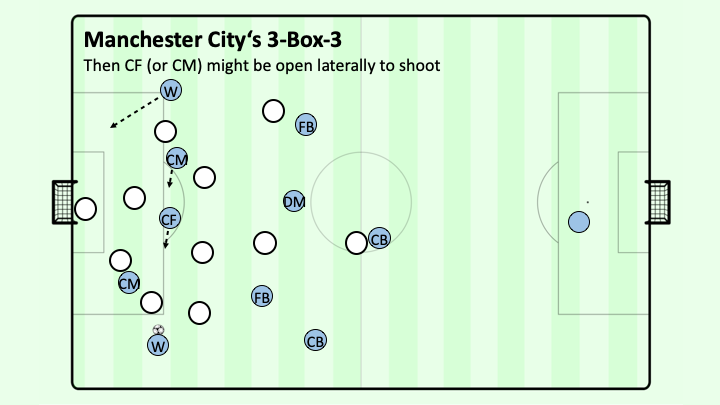

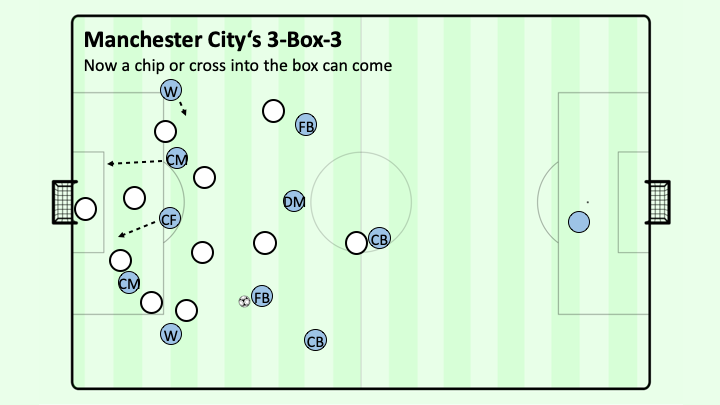

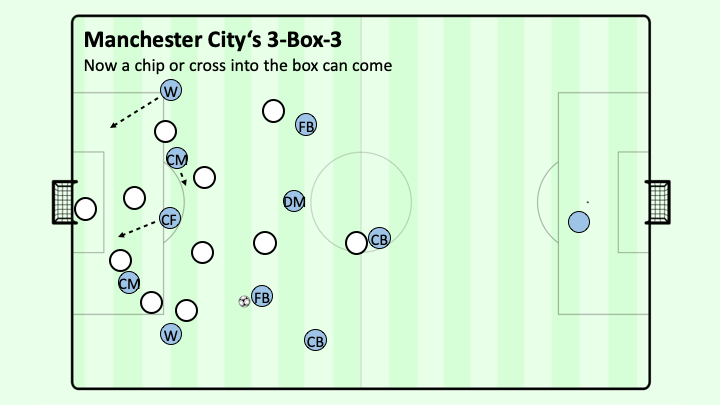

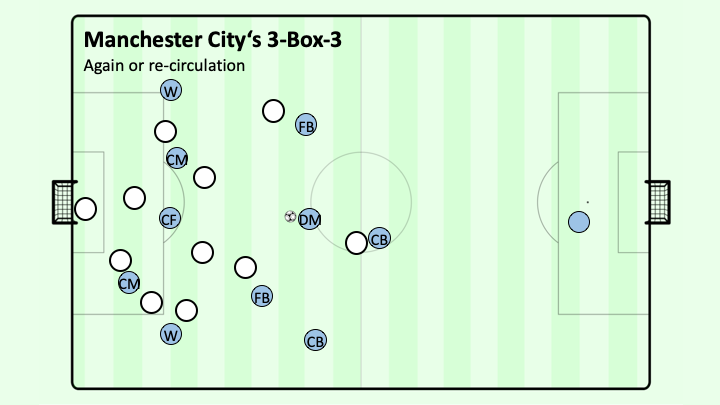

Death comes slowly, but inevitably. Unlike prior structures, Guardiola’s 3-2-2-3 can adapt to bigger changes precisely with smaller ones and still keep the upper hand. His managerial ability shows itself in the details. Some examples? As soon as a center back jumps to press the false Nine, either he will drop further, move laterally to force the center backs to change assignments and lose space plus time for defending or there will be depth runs by the midfielder or wingers. When the opposing winger tries to cut the connection from Gündogan moving wide, the moment the opposing winger moves to the side, Gündogan parries with a movement inside in the ensuing gap. If a full back tries to correct or cover his team mate and defend City’s wing movement by pushing a line higher, a run into depth the moment the step out has been started will be the reaction and, if not reacted to, a dribble inside by Silva or Gündogan will follow just after receiving the ball with a dangerous attacking situation as consequence. And, if in doubt, play home, go back, start new and use the ball circulation to let the opponents run until their heads and/or legs are tired and their defensive organization destabilized.

If something is not working constantly, Manchester City will still mostly at least be able to keep the ball – among other factors, also because of the width in their first line and Ederson availability as ball playing goalkeeper. An adaptation could be either to create more presence centrally, by moving into a diamond instead of a box midfield.

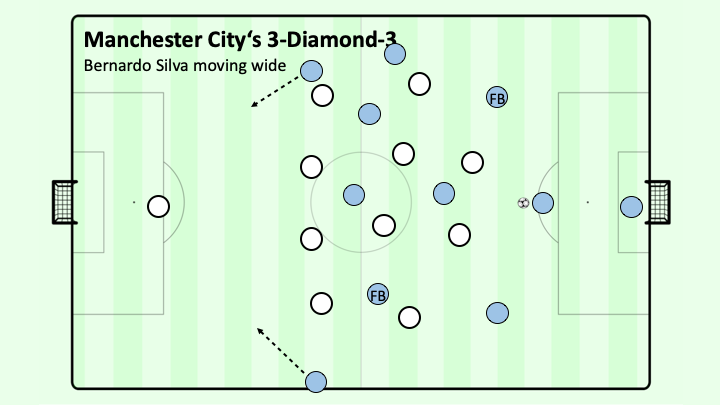

Another one is to go very wide and at times even lower with their wide midfielders. Gündogan’s timing and decision making is fantastic when doing so, as are Bernardo Silva’s dribbles from the side into the center when he is tasked with this responsibility. In some games it might happen on both sides constantly, in other games only one player will do so and, perhaps, the full back aka auxiliary center back will move wider to create more of a 4-2-2-2 positioning but with a midfielder in the full back position and Cancelo still joining Rodri in the center, even dropping centrally if the oppositional pressure forces them or it opens space in the center. Unsurprisingly, this positioning out wide seems to be one of the most complex “if-then-choreographies” by Guardiola’s team.

Guardiola’s Wing Brilliancy

The wide midfielders often start wide and move inside, instead of the other way around. Why? If they start inside and move outside, it’s harder to get the timing right because of the running speed and body position – which in turn influences the body shape when receiving because of facing outside when trying to get into position faster. If they start wide, they will either receive it on the proper foot facing inside and being able to immediately penetrate the middle from the inside instead of facing outside and nodding to their angry coach whilst under pressure. Also, by starting wide they try to provoke the opposition to press from a wider position – coming inside fast is pretty easy with the already open body shape and then receiving the ball centrally while already being on the run towards a dribble in the middle with the other midfielders (which could nominally also be strikers or full backs when in defending organization, as we know) supporting and the wingers offering deep progression options.

Add the tremendously coached details over the course of the last games to it. At the start of this structural change, under pressure the wide midfielders would sometimes come closer centrally and the wingers would try to support the center back when pressured. A few games later, this rarely if ever happened anymore and the wide midfielders would find position and timing more often, earlier, faster. Fast forward another few games and the wider central midfielders behind the wingers would constantly look at the oppositional full back (does he defend forwards?) and the deeper central team mates (Rodri, Cancelo) at first.

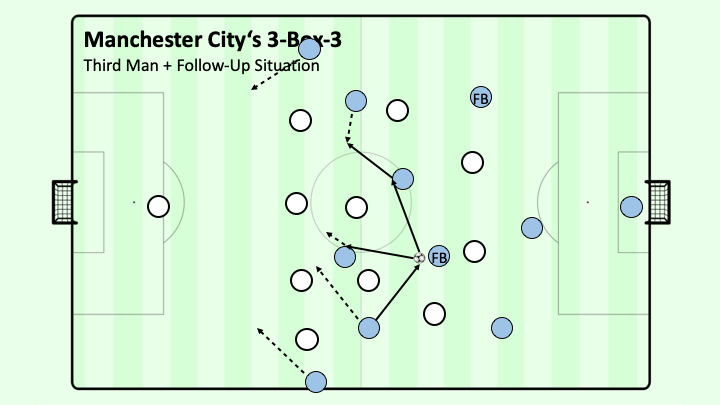

Playing over the third man to them or dribbling past the opposition would not only happen, but be perfectly supported by good angles for support of the deeper central midfielders with the center forward being positioned centrally behind the opposing midfielders and the other central midfielder being positioned on the ball far side behind the opposing winger. The moment the opposing full back would try to press forward onto the wide central midfielder, Manchester City’s winger immediately threatens with a deep run for a ball over the top or to enable more space and thus time for an easier ball protection by the wide central midfielder by pinning or at least occupying the oppositional full back mentally. Even if the opposing full back tries to cut the connection without losing time, the wide central midfielder will probably be able to dribble past him towards the middle. That is the reason why there is a slight angle between wide central midfielder and winger: to enable a simple counter-directional dribble for the wide central midfielder.

“The third man is impossible to defend, impossible … I’ll explain what it means. Imagine Piqué wanting to play with me, but I’m marked, I have a marker (defender) on me, a very aggressive guy. Well, it is clear that Piqué can not pass it to me, it is evident. If I move away, I’ll take the marker with me. Then, Messi goes down and becomes the second man. Piqué is the 1st, Messi the 2nd and I the 3rd. I have to be very alert, right?! Piqué, then plays with the 2nd man, Messi, who returns it, and at that moment I’m an option. I’m now free of my marker who has moved to defend closer to the ball. Now I’m totally unmarked and Piqué passes me the ball. If my marker is looking at the ball, cannot see that I’m unmarked and then I appear, I’m the third man. We have already achieved superiority. This is indefensible, it’s the Dutch school, it’s Cruyff. It is an evolution of the Dutch triangles. (…) To look for the third man is, for example, that the central players have the ball and one of them is always open because you always have one player more than opposing strikers. In that case, Puyol has the ball and goes up, up and up until a defender challenges him. If the defender who tries to stop him is my marker, then the third man happens to be me! If it is Iniesta’s marker who moves to challenge Puyol , then Andres is the third man. And so we seek superiority in any area of the field. You make a three against two, you win and you have the third man. We advance positions up the field” – Xavi Hernández

If the full back stays and it’s the opposing central midfielder trying to keep Gündogan or Silva (or de Bruyne) on the outside, the center forward might be the third man to progress forward by using the winger for the lay off or, as before, the central midfielder will be able to progress after receiving as third man. Close all that open space and it’s a back pass and a fast switch to the other side thanks to the width in City’s first build up line. Keep them on the side for too long and passively, then Cancelo and Rodri will have time to open space for each other by a simple counter movement. Track both of them and close the back pass on the side lines to the side center back (Walker, Stones, Dias, Laporte), then the central build up player (Dias, Stones) is open again. If the opponent somehow is able to defend all of this when City receives it on the side, City’s individual quality enables to stay in possession and pass back to the goalkeeper for a re-start. Moving from one side with having to commit so many players there to the other side can hurt mentally; and after some of these switches also physically. This constant overload on the sides with a 2v1/3v2 is the main reason why they can recirculate so often without losing the ball.

“The secret is to overload one side of the pitch so that the opponent must tilt its own defence to cope … so that they leave the other side weak. […] Then we attack and score from the other side.”

In a way, a comparison to historical chess development can be undergone. Siegbert Tarrasch formulated various principles, among them (based on Wilhelm Steinitz) a direct control of the center utilizing pawns. The so-called “Hypermodern School” (represented by Richard Réti, Aron Nimzowitsch and Savielly Tartakower) instead viewed some of these concepts as too dogmatic and rather proposed an indirect control of the center through distant pieces, inviting the opposition to push their pawns in the middle and then either target them for attacks or even use them to pin the opposing pieces within themselves. Especially Aron Nimzowitsch was very important for this, although hypermodernism still classifies as addition or extension to the foundations of chess theories which are still based on more classical theory (though perhaps not too surprising for avid, long-time Spielverlagerung readers).

Similarly, Guardiola’s positioning with the wide and high wingers threatening depth, the build up with three in the first line and the positioning of the wide midfielders seemingly targets the same provocation as the hypermodern school of thought, to quote: “Delay direct occupation of the centre with the plan of undermining and destroying the opponent’s central outpost”. That’s more or less exactly what Guardiola’s structure does to the opposition with the obvious occupation of the center when it opens in order to conduct a quick, decisive attack – by moving inside with the wider positioned central midfielders, the dropping center forward who tries to receive on the turn and carry the attack forward or the wingers going deep. The use of a false Nine was described with a similar idea behind by Guardiola himself, by the way:

I like the strikers arrive to the positions, not stay in the positions.

Obviously, not just these (somewhat hypothetical) strategical ideas, but the tactical specifications, amount of details and fantastic coaching are also visible in other aspects of their positional play: The ball movement of Dias to manipulate passing lanes, the use of the central midfielders to open space for the pass-after, etc. The constant and streamlined communication-decision-execution process on the highest level from more or less every single player with clear cues (and reason) is clearly (in parts) a work of coaching – unsurprisingly, considering Rodolfo Borrell and Juan Manuel Lillo are sitting on the bench with Guardiola, besides other competent staff on the training pitches.

When the center forward is dropping, for instance, he is first looking into the direction he is coming from to see if the center back is following him, then he is secondly searching for the nearest midfielder to where he is coming in order to see if someone is picking up that assignment. His team mates in center midfield will then either open space for him by moving away when marked or occupying angles for one touch passes and then, if needed, react by finding new positions when a dribble starts. And this is besides more obvious principles as passing the ball at the right moment into the best direction for the follow-up action with the right speed for it. This coaching quality (paired with their amazing individual player quality) and visibility applies to other phases of play as well.

The Immortal Game

One main thing is obviously the Domino Effect on Defending that ManCity’s Attacking has. Positional Football has the obvious feeling that you always lack one player (function, or task) for perfect spatial occupation: Width in the first line, depth in the first line, width in the last line, width in between, overload in the center and a deep option in the last line ; the obvious solution is to push up the goalkeeper (4-2-2-3, for instance), but it’s also the most risky one. Guardiola has solved it differently, even since his Barcelona days – the deep central player is gone (aka center forward) and instead all the other functions are fulfilled. The center midfielders, the wingers and the back three give width with the midfielders coming inside, as already mentioned.

Due to the connectedness of all phases of play this consequentially means that upon losing possession all ten outfield players occupy a position that is not the deepest, furthest forward one. Mix this with the short distances and short passes, a clear structure, clean patterns, high passing speed and the ability to dribble which leads to easily observable pressure situations and transition moments that are not only “prepared” well, but also lead to squeezing the pitch early and fast enough to counterpress properly. Combined with some tactical fouling and a fantastic rest defense it’s barely possible to score against this City team in transition anymore. The quality of the positional structure and its patterns and principles leads to equal quality in transition and, thus, defending.

More organized defending situations from a more typical defending shape – with Cancelo or Zinchenko back at full back – means that Guardiola has succeeded in creating a nearly complete team, which

you can’t comprehend it – it has to be seen and even then it can’t be believed

that such a well-rounded team still specializes this strongly on one aspect/phase of play. Without much fuss, matter-of-factly and Westfalically down-to-earth we can state that it’s not just their positional play, but also their press, classical defending and even second balls that are, frankly, on the highest level. Their back four pushes up constantly on back and sideways passes or the opponent not being able to play the deep ball, their full backs defend forwards really well, often starting bravely higher than the opposing wingers and shadowing him with the center backs pushing until the byline and the whole unit being quite good and constantly active in their search for pressing triggers in general.

Their formation for this is flexible, with a 4-3-3, 4-4-2, 4-2-3-1 or a 4-2-2-2 which looks more a 4-2-4-0 as the “center forwards” shadow the center and the wingers are constantly looking to trigger the press and sprint at the center backs – with, especially, Foden behaving like Rangnick’s wet dream and Guardiola’s in-game coaching being uniquely fast. Thus, counterpressing, squeezing on longer balls and supporting team mates in duels are no weakness anymore and their use of the offside line near-perfect. Even individually, Walker nowadays defends better than even or at least on par to most Champions League caliber center backs with using defending feints in their few defending moments to cut oppositional wingers and forwards from their team mates in time. So, until now we have covered how City keeps and does not lose the ball whilst preventing scoring chances of the opposition and winning the ball back. The most important aspect of scoring goals is not only tremendously under-coached in football, but under-valued when analyzing Guardiola’s teams.

When Scoring Becomes A Craft

Do not search for a solution, the solution has to present reveal itself.

This heuristic mostly is used to refer to passing in general, but at City it seemingly refers to the process of scoring in itself. They are not trying to force a goal attempt and get a shot off, but instead the circulate the ball and move the opposition as quickly and frequently as possible in order to generate a situation for a shot attempt. Without the ball, the opponent can’t score – and until the opponent is not disorganized, Manchester City is defending with the ball whilst trying to de-organize the opposition actively.

This might sound like a paradox or, worse, an empty phrase, but it’s actually a very tough balance and coaching challenge to circulate without becoming passive, defensive or without intention while also not forcing situations, not passing to players without further chance to progress the attack or making mistakes due to miscommunication while deciphering if a depth run is there to receive the ball and progress or to enable another circulation or a different progression option.

You have to pass the ball with a clear intention, with the aim of making it into the opposition’s goal. It’s not about passing for the sake of it

An open (i.e. unpressured) ball while looking forward will immediately lead to deep runs, even if they ultimately are done to open space between the lines to pass there on the ground for a quick turn and fast progression with De Bruyne, Foden, Gündogan or Silva. Still, the ball over the top will only be played if clearly open or no other solution due to pressure of the opponent. Normally, of the utmost importance, is that a lot of passes will be used patiently without risking to lose the ball to reach a situation around the opposing penalty area where ManCity can involve a lot of players with good cover defensively. From there, they tidily work their way to a goal scoring chance.

Using their wide wingers, a 1v1 or 2v1 on the wing might be outplayed.

If this is not possible, then there will be runs behind the defense to play it behind the back four and then square it in front of the goal or do a cutback pass.

If the opponent defends this, a square pass in front of the defending line might open up to shoot from just on the edge of the box.

If the opponent congests the space and opens the space backwards, then using the inverted full back or the defensive midfielders will be done to move the ball into the box.

Countermovements are used a lot.

If the opponent presses well, the side will be switched or it will be progressed through the middle.

In some situations, the fullback or even center back might recognize space to advance and try to utilize this.

The constant presence and personnel at the opposing box are the main reason why Manchester City are scoring a frightening amount of goals per game since changing to this system (although they were not too shabby before, weren’t they?); again, the phases are interconnected and by arriving at the box patiently, but together, there are a lot of possible ways to finish the attacks off. And when they choose not to finish them off immediately, opposing teams still have the constant feeling and need to defend their goal, blocking possible shot attempts instead of preventing further progression or passing which in turn Is creating even more of an overload in front and around the defending shape for City to circulate and pin the opponent in their box until the next, better scoring opportunity arises from this circulation.

Does Modern Day Defending Have Some Questions Left?

The premise of this article and its main thesis is that Guardiola has solved traditional defending; still, a short look at possible solutions should be done. In the end, Guardiola’s team will still continue to lose some games and perhaps even get knocked out of various competitions (though the thinking in here is that it’s due to a change of style, a bad execution or a fantastic opposition). Alas, even the greatest teams can be defeated by an opposing team that is lesser, but perhaps more specialized – sometimes by evading their strengths instead of trying to challenge them. Besides some less obvious ideas (asymmetries, new concepts or extremely good execution), a proper positional play and set pieces could prove a way to go in the future. Yet, the question is whether typical patterns in usual schemes might be more useful than others or force Manchester City to bigger adaptations and specifications.

First things first, teams can either choose (on a very basic level) to either defend zonally or to man mark. If a coach chooses the latter, the team is obviously in danger of losing their respective assignments due to City’s rotations, individual qualities and involvement of the goalkeeper, so as a coach you would have to pray and, ideally, resign from coaching altogether in this case. Obviously, a mixture of zonal defending and man marking can be done while one should not fret too much about these concepts nor about formations, although it can help in this type of discussion. If you go zonal, the question is how you distribute the zones (which his more or less the biggest singular reason for formations).

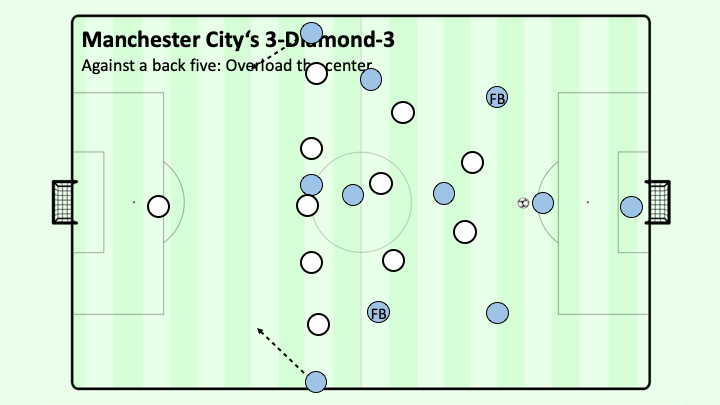

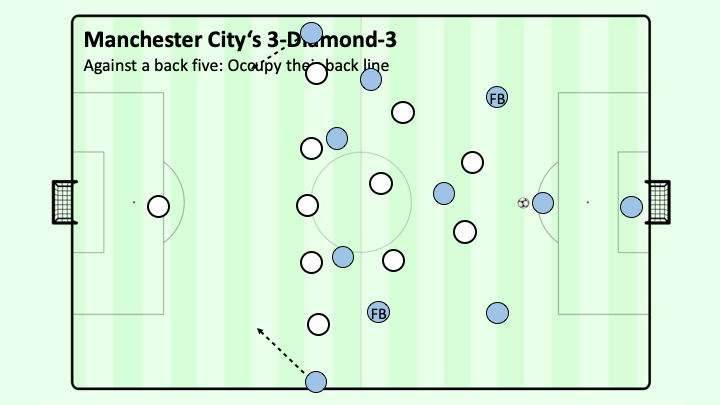

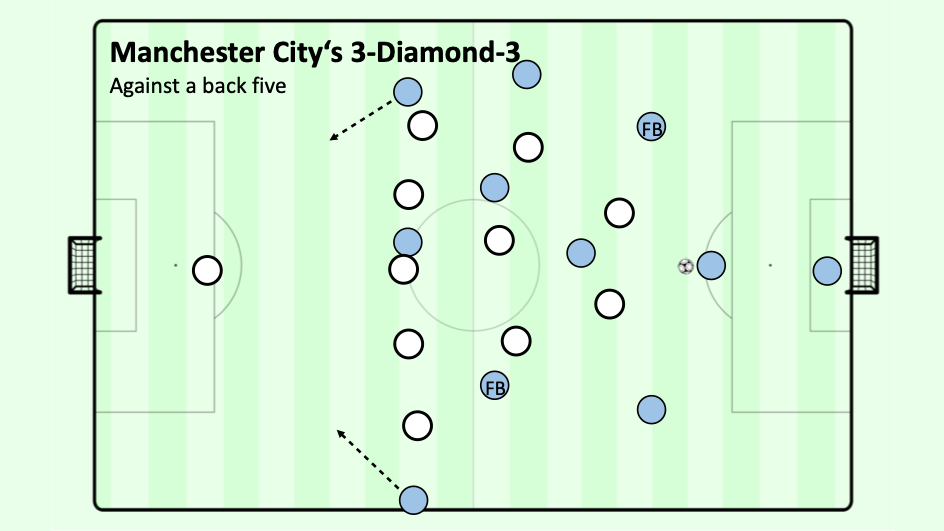

Because it’s not allowed to field two goalkeepers (or hey, none), for the sake of brainstorming and discussion the number of defenders in the first line and their tasks should be discussed. If you play a back four, they will kill you through the sides and with their wingers because you lose players in your back line to step out. Try a back five and they will kill you through the center and with their back line because you lose players further up to press them.

If coaches get a bit more sophisticated, they could think about pushing the back five players forwards to defend and, perhaps, risk a head ache due to the constantly changing assignments. The problem is that players will usually want to push up within their zone and only up to a certain point; City’s players are constantly looking for these types of opposing movements and then either dropping further or moving laterally in order for the opposition to lose their organization or have to switch assignments over big distances with City’s using counter-movements to attack these spaces. Doing this with a back four instead of a back five with a 4-1-4-1 in order to overload the center and keep them on the wings makes it even harder, so a perfect day in terms of decision-making in these situations would be needed. A 4-1-4-1 looks like suicide, considering this.

So, why not 4-2-3-1? Southampton tried with a 4-2-2-2 and 4-2-3-1 mix and only Hasenhüttl’s near perfect pressing background prevented comical wing defending (on the contrary, it was a really good performance in both games). With their two pivots, the second striker / the center forwards will be either lured out or played past. If you defend zonally and pushing flexibly into a 4-4-2 against more narrow build up and 4-2-3-1 against wider build up, it can work but is a tremendous Denkaufgabe (hopefully not becoming a Denk-Aufgabe).

Worst case scenario for City: Rodri or Cancelo drop to create a 4v3 in the first line, if Ederson can’t be enough support. If center backs react too much to their striker or wingers, the midfielders will go deep through the channels instead. This is the main reason why most team man mark them with midfielders now and open the center where the center forward then thrives on a good day; stepping out with the center back will lead to the aforementioned rotations, moving laterally with the central midfielder from the other side will just result in another switch until the opposing midfielder can’t reach the wing in time to support the full back.

Now… 4-3-2-1? The constant circulation might not help them bypass the midfield, even if teams would not mind them overloading the middle and position themselves in every single gap of the opposing midfield line, but it would lead to third man advancements. Playing through the third man in the middle then will regularly lead to progression and switches. If the two attacking midfielders (the “2” in the 4-3-2-1) stay inside all the time, the defense might cope and shift in time but winning the ball looks impossible, if not a dystopia.

In a 4-Diamond-2, teams might have the best chances to actually put them under pressure, but the forwards and midfield would have to be nearly flawless to prevent passes from the back three into the midfield while also preventing progression from the lateral center backs. Also, a single switch might end up catastrophic as it will be very hard to recover in time to defend the box.

Concluding, go 4-Diamond-2, a narrow 4-2-3-1 or 4-3-2-1 and you might just be lucky enough, if you can run all day and all night, to defend the middle. Except, you know, they combine through the small spaces or after minutes of running from side to side, one player either gets tired, loses patience or, as you know, becomes more human than City’s and does a mistake.

Thus, back to the drawing board it is: If the opponents react with a back five with side center backs stepping forward to help in the middle against the two wider central midfielders, they will move outside and drop further the moment they realize this.

If the wing backs instead try to defend this pattern, a diamond staggering in the center could happen instead or deep runs by the wingers will be the solution – never mind your wingbacks facing a near impossible task of left footed Bernardo Silva and right footed Gündogan or De Bruyne dribbling inside from the outside and forcing you to switch on the fly or lose your position.

The overload in the middle will continue to stay alive in this situation, because the center forward will immediately (or, rather, at the latest) drop in the moment the central midfielder is receiving out wide. Depending on where their attacking central midfielder is, he will either drop on the side of the ball or on the other side, often combined with deep runs from team mates (either the wingers or even other central midfielders). A 3-1-4-2 was used against Everton’s 5-3-2 just a few days ago, where both center forwards can either pin the opposing center backs and prevent them from defending forwards when the central midfielders are more narrow or the center forwards themselves drop into central midfield flexibly and overload space there whilst the pattern of the center midfielders starting wide and moving wider is used.

Still, a back five can work if all these constant, rapid switching assignments function well or if there is a team that can ignore changing zones and continue to track an opposition; for instance just like Atalanta Bergamo which sometimes pushes their lateral center backs out to press very far and at times they end up pressing opposing full backs when Atalanta’s wing back is occupied by the oppositional winger. If either the variability or the player types to ignore the need for variability is acceptable, a back five might be a good approach. 3-4-2-1 / 5-2-3 might, again, lead to progression through the center into the gaps of the midfield whereas a 3-3-2-2 / 5-3-2 will be shifted around until it breaks with a consistent attraction of the strikers to move closer before playing around them and progressing, although an asymmetrical mixture of these two worked fairly well for West Ham United recently.

A 5-4-1 will prove too passive in the end, but could help win a draw – and a 3-4-1-2 / 5-2-1-2 will get killed much earlier, probably. Still, depending on personnel different variations of a back five might be interesting, even if the possibility of either getting outplayed or becoming too passive is pretty high. Compared to back four approaches, these variations seem harder to do for most teams but pretty helpful for suitable personnel. On paper, a more unusual variation might be the best: A proper back three might be promising, even if exceptionally risky against the deep runs of ManCity’s midfielders and wingers.

To accomplish this, an unusual, high-risk but also potentially high-reward approach would be a 3-3-3-1 with the first line of defense being wider and the next two chains of three being quite narrow to close the center. In this case, the two wingers would prevent easy passes to the central midfielders and press the center backs whilst shadowing the midfielders. To prevent reaching them over third-man-patterns and progressing further, the second striker should stay between City’s two midfielders (which, to remind you again, is created with one full back) and shift to the midfielder nearer to the ball in the right moment. Instead of wing backs, two central midfielders would be used to flexibly defend the flexibility of ManCity’s attack, mainly their central midfielders. Similarly to the approach of the line in front of them, the central player is covering both runners besides him and controlling the center – by either dropping into the back line, tracking depth runs or marking City’s striker when he drops into midfield. The lone center forward in this idea would support the second striker and closing gaps in midfield or defending back passes and re-circulation options, mainly the central center back of City’s back three.

Ultimately, any theoretical solution will be a question mark in terms of practicality. It is not just a question of tactics and execution (with the last example being a pretty extreme candidate for “barely possible”), but also a physical one. How prepared are the players to do these actions over ninety-plus minutes? The higher you press, the more fatigue is going to become City‘s twelfth player. Teams like Southampton, Liverpool or Chelsea started off quite well, but faded away rather drastically in the second half. Also, it might not even be more profitable and less exhausting than pressing – it’s just less visible. Their counter pressing and rest-defense might be the most annoying aspect of their positional play in this regard.

On the other hand, if teams choose to defend deeper, the less space and time there is to start the transition, even if there is more space in behind of City’s defense. Crystal Palace’s 4-5-1 worked well, but still conceded four (after set-pieces) without much ball recoveries, possession or successful counters. The problem would be to expect an approach not only working constantly, but also being enough – playing against Guardiola also means playing against a very good team that has individual qualities to solve problems with the in-game coaching behind to adapt strongly. With the new structure explained in the article, adaptations can come quicker and without bigger changes, too. Merely pushing Walker from his center back position further towards full back again or even just adapting distances and patterns in their movement or fielding different players in different positions can mess with more specific ideas of the opposition.

It might sound too trivial, but fielding De Bruyne or Silva as “wide center midfielder” is already quite the difference, employing Zinchenko instead of Cancelo gives the game a different focus, switching Stones or Dias with Laporte changes the rhythm and using a specific type of center forward are all already huge differences on that level. It is not the same when the ball arrives in the back of the opposing midfield with De Bruyne pushing it forward, Silva carrying it past opposition, Jesus turning to the sides or Agüero always being focused towards the box. Especially, as City has a different focus in the last third anyways, being more goal-oriented and mostly being able to push into the last third sooner or later, even with, perhaps, less suiting personnel for their circulation.

New Questions Needed

To conclude this small brainstorming session, Guardiola seemed to have solved both sides of the same coin: “Space-Time”, as many of La Masia’s absolvents (most notably, ever repetitive in his interviews, al-Sadd manager Xavi) have come to call it. The concept is relatively straight-forward and less complicated as it might seem on the first look. In the end, it is the premise for the subsequent assumptions and ideas of the Positional Play Concept and also the general base of how football on the pitch actually works.

This older Spielverlagerung article on the (orthodox) principles of positional play was already mentioned in this piece, so here will only be a short discussion about the “space-time”-concept in relation to the style of play and success of Manchester City right now. Regarding this “space-time”-conceptualization, there are some fairly logical, objective assumptions to be made.

First of all, space has to be manipulated on the pitch and it is done so together (one explanation by Domagoj Kostanjsak here). Concepts of width and depth or staggering between players is mainly used to explain these principles. Yet, on a very basic level it is even simpler: By trying to become a passing option, players occupy oppositional players. If they are neither too near nor too far from their team mates (through good distances and angles to each other) and from the ball, the opponent will be stretched out between each other as they try to defend the passing options. This, in turn, opens space.

In positional play, it is of utmost importance to not take away functions from an team mate by standing too near to him but also not too far from him – whilst doing the opposite for the oppositional players. Doing so, the attacking team will either have a lot of small openings or the occasional bigger ones – in the latter case, the passing options within the smaller openings are the ones opening space for the passing options in bigger gaps.

If these gaps are more or less of similar size, in positional play you will either try to lure opposition to close some even more by baiting them with short passes and dribbles there or a player with the quality to capitalize on these small openings will be looked for (see: Messi, Lionel). The latter would be called “Qualitative Superiority” whilst playing to a free man who has a lot of time to turn – basically a 1v0 – would be “Positional Superiority” (or, if you want to start a definition war, created through “Positional Superiority” on team level achieved by good collective actions on the pitch).

“The principle idea of Positional Play is that players pass the ball to each other in close spaces to be able to pass to a wide open man.” – Juanma Lillo

Not only team mates can open space by trying to become a passing option, but also oneself – for instance the typical winger movements where the winger would drop first in order to go deep afterwards into open space or go deep first to then come and receive with more space to turn afterwards. Still, without connections (available team mates for a follow-up action or an individual goal attempt), the opposing team will be able to defend such actions fairly well by involving more defenders. Thus, numerical superiority (or, rather, preventing numerical inferiority) might be needed, if the either the positional or the qualitative superiority are not enough to progress directly or enable a progression option.

The so-called “superiorities” of the Seirul•lo school of thought from Barcelona (positional, numerical, individual, dynamical and socio-affective, though they can vary depending on publications) are mainly created through principles of position in the space of the pitch, relating to opposition and team mates. Guardiola’s algorithm regarding spatial structures seems finished with this 3-2-2-3 base. In some opinions about positional play, fairly rigid structures with specifications of a minimum and/or maximum number of players in one vertical or horizontal line are given.

Guardiola seems to have broken with these principles and focuses on the superiorities and player functions as such more and more. For instance, besides the aforementioned definitions of superiority, there are categorizations for spaces that revolve around the ball – the “intervention space” for the space directly surrounding the ball, the “mutual help” space for the space in the vicinity of the ball and the “cooperation space” for everything further away from the ball. The logic in this case is that there are spaces and there are (inter-)connections and (inter-)actions within these spaces that are relevant. Through this definition, the thinking is moving away from formation lines (that are not clear and clean on the pitch as they are on a tactics board) and towards connections of players, their possibilities, passing lines and dribbling paths and phases of play within the game phases.

On a team level, the structure improved and optimized recently, has a useful distribution of players to accomplish these superiorities and interactions constantly and flexibly without too much player movement and instead more ball movement (a thing, that Guardiola himself has mentioned as the biggest improvement). If the opponents control the center, City can evacuate it and penetrate it from to the sides, drop with the center forward into the vacated space instead of moving inside with the far central midfielder – so Gündogan or Silva as each other’s match on the other side do not relinquish their respective control of both (center and wing), but keeping their qualities in these spaces with numerical superiority always being focused on the wing, but positional or dynamical superiorities in the middle and qualitative superiorities, ideally, everywhere.

This spatial manipulation and creation of different kinds of superiorities, flexibly and dependent of the oppositional idea by passing with the same intention and unity as a team, has been perfected through Guardiola’s new structure – at least, for the sake of this article’s hypothesis. The first answer of the “space-time”-question has been given; and it in turn is heavily connected to the second part. Besides this positioning, there is movement happening in order to accomplish this or to find a new, better positioning – direction and speed come into play here, which are the vastly harder part to conceptualize and position is connected to them through timing (“moment”), which in turn is the hardest part to coach and execute.

Obviously, the more space players have, the more time they will have. With more space and consequently time, finding solutions for the game situations at hand will be easier (in most cases and situations), at least for most players in this world. If a player’s first step when running in behind the defense is already an offside situation, the adequate connection with his team mate trying to make this pass will be harder than if there are “more steps” as possible time frame to make the communication, decision and execution of this interaction. And after all, speed is fairly adaptable, even if hard-capped, with position being more or less the opposite of this.

And, mirroring this, defending will be harder for the opposition if they have to control and cover more space with, in their case, less time to defend these spaces. Thus, even with time mainly being a consequence of space, players can still manipulate both. Defensively, pressing traps are an example for such. Timing is what connects spatial aspects between the players and between (inter-)actions.

“Positional Play does not consist of passing the ball horizontally, but something much more difficult: it consists of generating superiorities behind each line of pressure. It can be done more or less quickly, more or less vertically, more or less grouped, but the only thing that should be maintained at all times is the pursuit of superiority. Or to put it another way: create free men between the lines.” – Marti Perarnau

Manipulating space is fairly straightforward and, as is the thesis of this article, on a team level perfectioned by Guardiola with this structure. Manipulating time is rather hard to analyze, describe and coach, even if some examples are pretty clear and clarifying. One often mentioned example is the concept of “La Pausa”, which can be visible in a lot of different situations.

In the end, manipulating time has to follow an intention – a situation, where a maximally quick switch will be the only way to keep the solution on the other side alive or where a short halt will give a team mate time to turn before receiving or find a better position or open another passing option by luring opposition away. What’s special, is how every player seems to understand that not only their positions are giving them space and time for themselves and the others, but the process of their actions and resulting movement manipulates the time on the pitch through timing and speed.

If a team plays with the same rhythm, never mind which one, the opponent will be able to shadow. If a team stops or slows down the game with a position where they can again accelerate from, the opponent will accelerate later from a worse position. If teams play with the same tempo all the time, the opponent will already be accelerating and, for instance, track down runs easier. A fairly straight-forward example revolves around their build up.

Unlike most teams, you will less frequently see Manchester City’s build up players bypassing space through bypassing team mates laterally in a quick manner. The occasional diagonal into the last line for a 1v1 of Sterling, Mahrez or Foden might be looked for, but most switches and circulations happen with a pass to a player from time to time, before bypassing the players diagonally or vertically when progressing. Before that, opposition will be slowed down and fixated on the spot. Get the opposing team on one side and fixate them there; not only positionally, but also with timing. Stop the ball, look for players, dribble very slowly, not even attempting to actually bypassing them.

How often do we see others teams either not stepping forward with their center backs and dribbling the ball, thus lacking the creation of an advantage and short passing lines? But even more often, nowadays at least, we see center backs progressing against a moving team, bypassing a press through a carry, instead of using the slower dribble to test their patience, lure them out and open space, before the circulation to the other side enables a clean progression later on. These ideas relate to the superiorities called dynamical or socio-affective, mainly. To carry out these superiorities specifically, it is important to speak the same language and ideally a language the opposition does not understand or just patterns they can not prevent.

There are 36 different forms of communicating through a pass, according to Bielsa – and it is not unusual to read about Barcelona’s academy where many of former graduates or coaches mention this as well. A very fast pass into the foot is carrying a different meaning than a very slow pass into space. This also relates to the aspects of “space-time” on a principal level and for individual interactions.

“Positional Play is a model of constructed play, it is premeditated, thought about, studied and worked out in detail. The interpreters of this form of play know the various possibilities that can occur during the game and also what their roles should be at all times. Naturally, there are better and worse interpretations. There are also players that never manage to adapt to this model of play, which however, are sensational players and they manage to contribute many virtues to their team.

But in general, the interpreters of this model need to know the catalog of movements that need to be executed in depth. As in any piece of music, one same score gives rise to many different interpretations: faster, slower, more harmonious… more or less a concrete interpretation that you like, but what should be kept in any case is that the tune is similar to the original. Positional Play is a musical score played by each team who practice it at their own pace, but it is essential to generate superiorities behind each line of the opponent pressure.” – Marti Perarnau

Yet, it is also important for patterns and on a team level. For instance, when the pressure is high and passes are going fast, there will be less time to come into positions to start patterns. If there is time for one player, there will be less for others – and if he can take that time for himself, for instance by a dribble or a pause, after his pass the next player should have more time usually. In order to play if-then-patterns accurately, certain passes lead to a specific situation and possibility. A ball lying on the ground, without oppositional pressure or ball movement, does not force a change of the situation. A dribble and movement off the ball does, even if a lot of teams and/or players do not react as much to them. A pass changes the situation always; and the further it travels, the more it’s the case. Positional Play is often described as a choreography (Perarnau even compared it to a musical play) and it seems that every pass is a trigger for a certain part of the choreography – depending on the oppositional situation (mainly, is there danger to lose the ball or not?), the own situation (mainly, is there the chance to progress immediately with good further connections?) and other circumstances (leading or not). A pass from the center to the wing will, in some teams, result in too little, too much and/or random movement. For Guardiola’s teams, there seem to be a fairly clear set of possible interactions or patterns for every pass (similar to what a lot of well-coordinated pressing teams are doing when trying to win the ball, especially when pressuring from the first pass of the goalkeeper).

On the other hand, this in turns means that defending will have to change in order to defeat Guardiola; spatial structures will have to force Manchester City to different solutions or take away the effectiveness of theirs, with the time component either destroying their rhythm through constant, maximally high-speed press or countering their changes of rhythm by doing so in defending while taking command of the options they have. This, though, seems harder than being “a Guardiola team” on its own. Still, it should not be forgotten, how well this team is not only coached, but also picked and put together.

Generating the structure with asymmetrical full backs while defending in various back four variations gives them a specific type of rotational dynamic and a fantastic defender in Walker with a fantastic pressure-resistant midfielder in Cancelo. Brighton Hove Albion tried to create a similar staggering based on their 3-4-1-2 defending shape with their wingbacks moving inside (against a 4-Diamond-2) and the center forwards moving wide in possession. Besides the lack of individual quality, it was just not the same.

To conclude, if Guardiola does not choose to beat himself, or his players decide to sleep worse again (or just play less cleanly, as happened already for some phases in the last games), his new puzzle seems to have little solutions, even if some puzzling ones might exist though, as it is expected. In the end, for Guardiola, his staff and his players it will be most important to continue playing like this, getting their positions, movement and sleep right through discipline; some lesser games have already happened recently.

So Long, And Thanks For All The Wins

“Primer és saber què fer.

Després, saber com fer-ho!

First, you have to know what to do.

Then, you have to know how to do it.”

The history of football is plastered with hundreds of tactical inventions, thousands of variations of patterns and infinite adaptations battling each other with some ideas doing out, others switching paradigm governance in a somewhat repeating cycle and a few shaping the landscape of know-how standards. Guardiola, though, has declared war on the accumulated defending concepts of today and accidentally broken the game. Over the years, he seems to have found additions and hierarchy between his principles, found out that there is logic for when to be in your position and when to get into movement, how many details there are and how to coach them. And it is experience that teaches us which principles take priority over others; as mere words they all sound equally persuasive. This experience has led to a final point.

In most sports, every ten to twenty-five years truly special players, teams or thinkers would lead revolutions of knowledge. Jordan changed the NBA as did the Golden State Warriors (or, arguably, Daryl Morey). Others were even prevented of doing so by rule changes, which is thankfully not custom in football (though it should be contemplated upon set pieces and medium press in a 5-3-2, to be honest). Too late for it, anyways. The game would have not been the same after Guardiola, even after possible rule changes. Now, the game has to react to Guardiola and change itself. war has been lost, start a new one. But be careful, the following quote of Guardiola is already showing us that he is looking for answers without urgent questions already, becoming AlphaPeppio (though, honestly, look up at some stuff by AlphaZero!) before engines become his opposition:

I believe that soccer evolution will appear once the goalkeeper gets involved in the offensive play. I believe we will evolve to have this player. Build up phase is simple: I as a coach, as more players bring nearer to ball, the easiest. But then, once you have broken the first lines, you don’t have these players up there to create superiority. I mean, if you are having the ball here, is to get the superiority on the further zones to harm the opponent. If you bring all the players nearer, is ok butt then you can’t harm. You have the ball during initial phase for once your midfielder receives the ball, they can have advantage with the 10, wingers, Full backs, to harm there. Hence, if you want to maintain this damage, without bringing the further players the goalkeeper will help and allow to be done. But, of course, he has to have the skills, and be aware that you can use goalkeeper in the first actions but you can’t use him always as a CB. Because, if you lose the ball. they can score from midfield. You can do the first action, the second one, but then the goalkeeper has to come back to his position. I believe that the coach who has the courage to develop this will be the one to attack better in confined spaces.

The stylistic categorization of football ideas into “proactive-active-reactive-passive” was at times mentioned on this website and with relation to a proper interpretation of positional play. It will be interesting if there are further, even more proactive ways, besides utilizing the goalkeeper further, are there to improve upon the answer now or the new questions that football defending will start to pose sooner or later. Rotations, purposeful numerical inferiority or asymmetries could prove interesting.

This article was a collaboration project by various Spielverlagerung authors (Judah Davies, Pablo Rodriguez, Adin Osmanbasic, Martin Rafelt) and the fantastic Addis Worku (@addisworku431) who has watched more or less every game and press conference of ManCity in the last few seasons, with Borussia Mönchengladbach’s assistant manager René Marić providing feedback & additional information. A very decent piece on ManCity by Ahmed Walid – using the Gladbach games as examples – can be found here and here.

5 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Gwanjun May 4, 2021 um 12:03 pm

When he was in Barcelona and Munich, he ultimately used 3313, and I think City is using 3223, so can I say that the two formations are similar?

Marco Taormina March 25, 2021 um 4:25 pm

Excellent article.

Quote: ‘…high-reward approach would be a 3-3-3-1…’ This formation is very similar to the Italian ‘Catenaccio’ used for the first time by Rocco in 1947

Konstantinos March 25, 2021 um 12:02 pm

good and comprehensive work guys ! in the article u mention that “if u play with a back 4, they will kill u through the side , if u play with a back 5 they will kill u through the center …” could u recommend 2 games -for me to watch- in 2021 that in your opinion were the most representative of the opponent playing with a back 5 and losing the way u so meticulously described in the article ?thanks.

Emmanuel March 25, 2021 um 11:51 pm

City 2-0 vs Newcastle 541 in December 2020 + City 2-0 vs Gladbach 4231/442 (2nd leg) in March 2021 are games that come to mind.

Miika Kurtakko March 24, 2021 um 10:49 am

The obvious answer to the challenge posed by Guardiola’s City formation is actually stated right in tyen beginning of this article. And that is to revert back to Cruyff/Ajax/Barcelona formation with a libero, two wide defenders, a halfback, two holding midfielders, number 10 (CAM), two inside forwards and a number 9 (striker). Nominally that would mean 3-3-3-1 formation. As City plays with false nine, there is no need for a pair, or let alone, for a trio of central defenders. Instead, what you need is a free man – the libero – to act as a security player to guard against any possible lapses or through balls. The job of the half back is either to mark the opposite false nine or provide assistance to the central midfield trio and assure that there is no numerical superiority in the centre of the pitch. Also, the job of the libero is to stop the third man runs. It is not hard to envision a future defensive model where the libero is supported by the (sweeper-)keeper in this job.

As for the question of zonal or man marking, the most likely effective model is a hybrid, where the halfback marks the false nine and the inside forwards track the fullbacks. Maybe also a new/old role will emerge, the role of the wide central defender, who plays as a combination of a tradional stopper and a full back without the support of the wingbacks like in the systems of three central defenders at the back.