Conte’s men advance to quarter finals with dominant performance

Two of the Europa League’s strongest remaining sides met as Inter Milan took on Bayer Leverkusen in one of the first quarter-finals on Monday evening. Leverkusen dispatched Rangers comfortably over two legs, whilst Inter beat Getafe in a one-off tie. An intriguing counter lay in waiting.

Leverkusen’s build-up issues

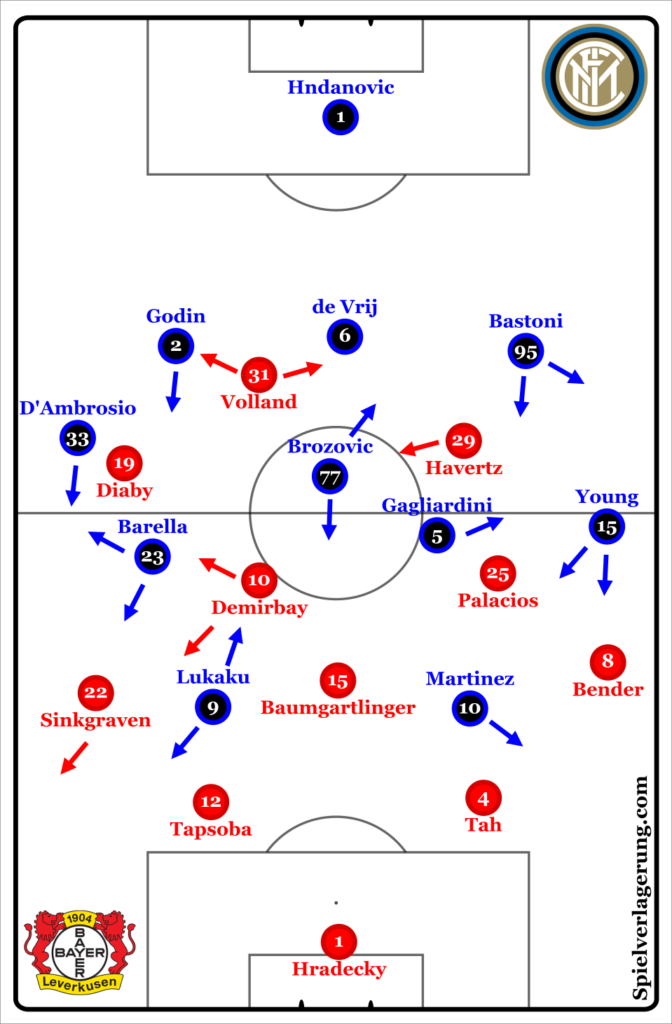

For reasons I will delve into later, Leverkusen often lacked free players in ideal positions to progress after winning the ball, thus often returned the ball to their goalkeeper, to give time for their team-mates to get into position. From here, their options were well restricted by their Italian opponents. Martinez and Lukaku favoured short distances to the centre backs over closing the 6 space, forcing a longer pass from Hradecky. Gagliardini and Barella marked Leverkusen’s 8s tightly whilst Brozovic remained deeper leaving Leverkusen’s 6 as the best option. However, Brozovic attacked this pass quickly from his deep start position preventing Baumgartlinger from turning out and advancing the play. From here, his remaining options were; a back pass to the goalkeeper and either a back pass to one of the centre backs, or the wide pass to one of the full-backs depending on the positions of Inter’s strikers. As a result, several build-up attempts were forced back to Hradecky, and the long giving extra time for the wing-backs to move up, and close down Leverkusen’s full-backs.

However, the Italian side’s wing-backs had differing roles in pressing, due to the asymmetry of Leverkusen’s forward line. Havertz as the right sided forward often had a narrower start position than Diaby on the left, a natural choice given their playing profiles. Additionally, Volland often drifted into the channel between Godin and de Vrij, adding to their pinning presence high on the left. In reaction D’Ambrosio remained deeper, slightly ahead of Godin but noticeably cautious in advancing to press, presumably as they wanted to prevent a foot race down the line between Diaby and Godin. Young on the other hand, was free to move up and signal his intention to close down any chipped passes towards Lars Bender. The result was most of Leverkusen’s build-up attempts played to their left side, and Sinkgraven in particular. With D’Ambrosio’s deep starting position, the responsibility to press Sinkgraven initially fell to Barella from his right 8 position. This became the key build-up situation for Leverkusen in the first half, and Bosz’ side consistently failed to progress from it.

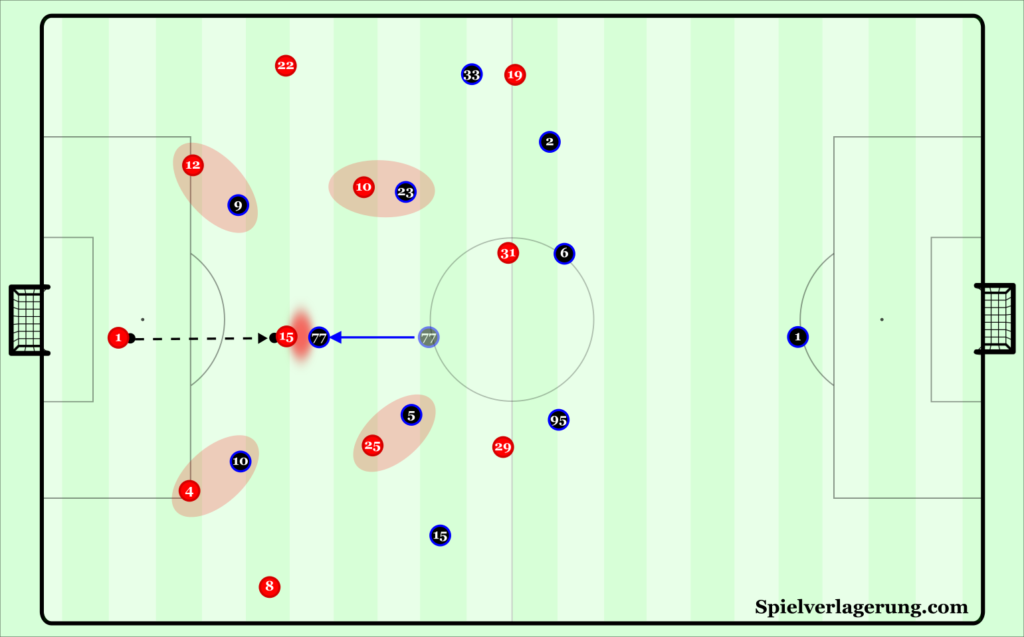

Since Barella had to move from his initial position marking Demirbay in the right half space to pressing Sinkgraven on the wing, he did so in a diagonal manner. Brozovic then had to move from pressing Baumgartlinger, to covering Demirbay. With Inter’s strikers failing to adjust from their positions blocking Leverkusen’s centre backs, room was created for Baumgartlinger in the 6 space. This was used sporadically, in the early exchanges, however the option was often recognised and played late, by which time their intention was read by Brozovic who was again able to press and arrive on Baumgartlinger’s touch. This meant the only options he could access were those his body position was already oriented towards. This created two related issues; firstly these options were not ideal since they were either in deep positions and/or wide ones (such as the goalkeeper or FBs), and secondly passes to them could be anticipated early and quickly closed down since they were in positions the ball carrier was already facing. With this severe and consistent difficulty in progressing, the German side began attempting to solve the issue with varied movements and slight structural changes.

Attempts to free Sinkgraven

Since Barella had to cover Demirbay when the ball was central before moving to press Sinkgraven, Demirbay attempted separation movements,increasing the distance between himself and the Dutch left back to give him more time in possession upon receiving, and thus more time for team-mates to offer him passing options. Initially, Demirbay did so by moving deeper and narrower into the 6 space, keeping Barella in a narrow position with him. When the Italian midfielder moved to press wide from here, Demirbay moved diagonally outwards to the space on his blind side. Yet, here he was quickly closed down by Godin, with the move ending soon after as he was not able to control the ball and find an option infield before the pressure came.

A variant Demirbay attempted was to move higher into a central 10 position, again further away from Sinkgraven. Now the distance was too far for Barella, so D’Ambrosio was tasked with closing the left back down. However, with Demirbay positioned so far away, Sinkgraven was further isolated. Demirbay could no longer provide support in the near half space and as a result Brozovic could focus more on blocking Baumgartlinger, leaving the pass down the line to Diaby as the only option which was simply overhit and easily defended.

Sinkgraven moves deeper

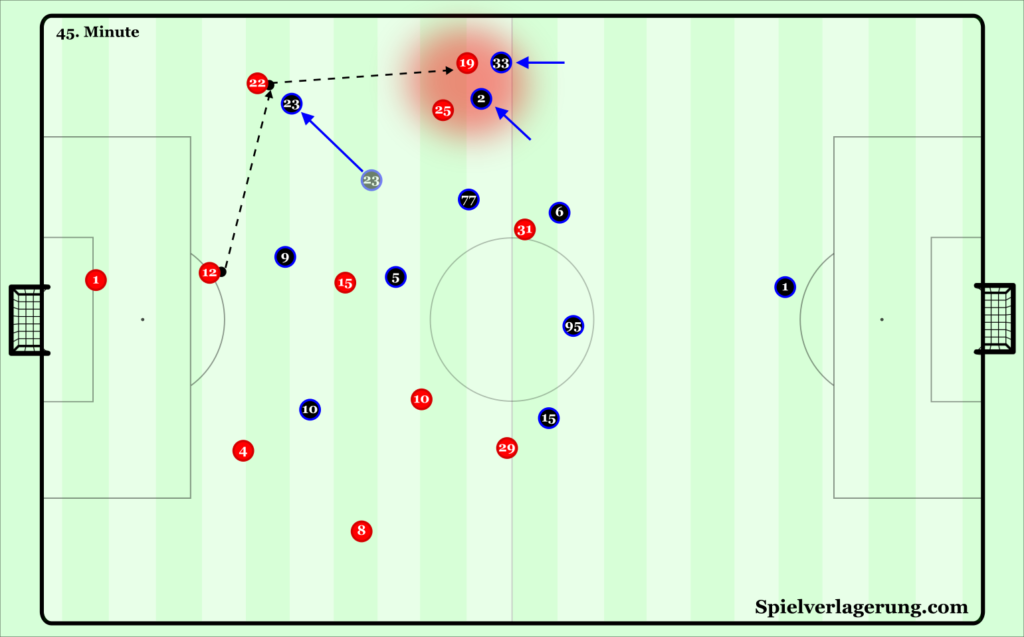

After around half an hour, Sinkgraven began to move deeper earlier in build-up situations into an asymmetric back 3 type structure, at times even receiving the first pass from Hradecky. With the left back’s deeper positioning, Barella was once again the one responsible for pressing him. This move drew Barella further away from the midfield, which could further open the near half space for Leverkusen to play infield.

However, this merely provided one better progression, with the following attempts no more successful than in previous structures. With their left back on the ball, Tapsoba failed to offer a back pass option, meaning Lukaku could simultaneously block re-circulating through the back line and threaten any passes into the 6 space. Barella’s diagonal pressing angle thus meant the pass down the wing remained Sinkgraven’s only option. The movements to target this space were consistently poorly co-ordinated with Diaby and the left sided 8 (at this point Palacios) both dropping towards the ball. D’Ambrosio and Godin could now simply support each other in pressing Diaby who often received back to goal on the touchline and without a viable option to play infield.

Barella’s pressing speed was a subtle but important point here. By slowing down as he approached Leverkusen’s left back, he was better able to defend inside spaces against any movement from Sinkgraven, reducing his ability to provide an option through counterdynamic movement. Diaby was now far easier to isolate.

Conceptual issues

“As has been discussed in the introduction, it can be more difficult to play against the pressure effectively due to the constraints of the wide space. However, the context in which they face pressure is quite consistent compared to more central positions and as a result a decision-making framework can be created to aid the full-back in playing against an oncoming presser from inside the pitch.” – MV, 2020

The German side appeared unprepared for the key build-up situation of the game, resulting in a lack of movement into positions to provide Sinkgraven with passing options quickly enough. Without prepared options, each player was relied on to recognise each individual situation quickly enough, and co-ordinate their movement with nearby team-mates to target spaces around the pressing player. This all had to happen quicker than Inter could close the ball carrier down, which proved too difficult for Bosz’ men. This provided consistent examples of the aspects brilliantly detailed in MV’s theory piece and the advantages of preparing players for such consistently occurring situations.

Problems in middle/final third play

Unfortunately for Leverkusen, their in-possession issues were not restricted to deep build-up areas, as they were almost wholly unable to break down Inter on the rare occasions they were forced to retreat into deep positions.

In these moments, the Italian side’s structure was naturally more focused on covering spaces closer to goal, than blocking options and attacking the ball carrier. The biggest effect was seen with the wing-backs deeper in the last line, and the 8s starting deeper and narrower. Leverkusen’s full-backs were now the immediately free players, as well as the deeply positioned midfield trio. However, they were unable to transfer this advantage to the final third as they lacked circulation against the grain of Inter’s defending. With a lack of opponents behind them, and out of the defensive line’s access, Inter’s midfielders were free to push out and press Leverkusen’s midfielders. This led Bosz’ side to several full-back to winger passes who were quickly shut down by Inter’s wing-backs, leading Leverkusen to circulate through their deep midfield line to face the same situation on the other side. They would then attempt badly prepared passes to a forward in the centre, which was easily defended by Inter’s aggressive defensive line.

Inter in possession; a stark contrast

Leverkusen started their pressing moments in a 4-3-3-0 type structure. Each of their front 3 focused on keeping a vertical line to their opposing member of the Inter back 3, but as a line remained just in front of Inter’s midfield line. Leverkusen’s 8s focused on defending the passing lanes behind the front 3, in the process marking Brozovic and Gagliardini. This encouraged passes between the Inter centre backs, any of which were used as triggers to initiate pressing. Passes to the half backs were closed at high speed in a vertical manner by the near Leverkusen winger. They were mostly able to prevent the half back from turning out and playing to the near wing-back by arriving to press as they received the ball and their resulting larger cover shadow. As a result, Inter’s wing-backs were hardly used in deep build-up situations, and they had to find ways to outplay Leverkusen’s pressing in the centre.

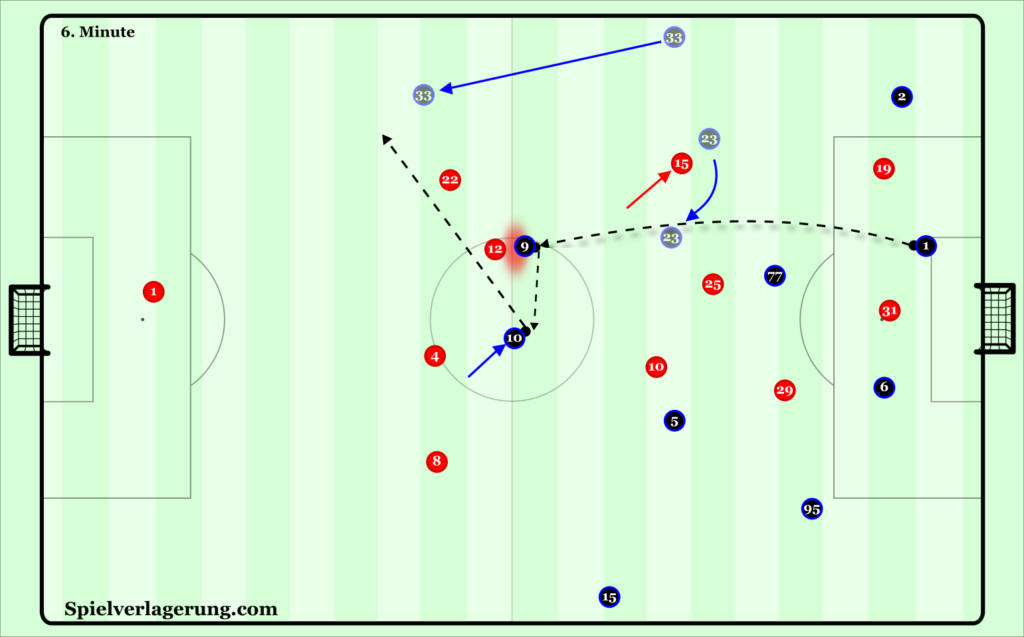

Barella’s role was key here. By drifting towards the right half space and attracting Baumgartlinger’s attention, he reduced Leverkusen’s cover in front of their defence. Inter could thus play lofted balls towards Lukaku in particular, whose immense ability to protect the ball made this a stable option. Here the contrast to their opponents’ possession was stark. Conte’s side appeared prepared for the situations they created as they consistently provided Lukaku with lay-off options, with Barella making curved infield movements to support, Martinez offering a quick option to his right or running behind, and at times Brozovic offering directly below. The speed of these options being offered meant the rhythm of their attacks could be maintained, allowing consistent and quick progressions.

After around 10 minutes, Demirbay and Baumgartlinger swapped, with the former now responsible for pressing Barella. With the Italian midfielder closer to Demirbay’s base position, he had to shift less to press him, meaning he could combine this role with blocking the passing lane to Lukaku, or at least help win second balls in front of him.

Conte’s side however, adjusted their structure effectively to create new threats. With the wing-backs not involved in early build-up, they were sent higher into winger-esque positions. Gagliardini and Barella now moved wider towards the wing-backs’ previous positions. Additionally, Godin and Bastoni moved far wider in the first line. With the half-backs positioned wider, the pressing runs from Leverkusen’s wingers were now more diagonal, making it tougher to cover the outside spaces. Barella in particular, was now more accessible in the space behind Diaby on Inter’s right side.

The advanced wing-backs and the two strikers’ meant the Italian side created several 4v4 situations against Leverkusen’s defensive line. Given their wide positions, Young and D’Ambrosio were the ones initially with the most space. However, given the lack of cover in Leverkusen’s last line, simple movements could create a 1v1 in dangerous positions against their defence. With Young in possession, Martinez made consistent underlapping movements, dragging Tah with him and opening the diagonal line into Lukaku who was constantly in a 1v1 with Tapsoba. As the Belgian striker has explained himself, that tends to be a dangerous situation. This situation led to both goals, and a number of other dangerous breakthroughs.

2nd half and conclusions

The second half was a surprisingly uneventful affair with minimal tactical changes which ultimately had very little impact on the game. With Leon Bailey coming on around the hour mark, Leverkusen now had high and wide wingers on both sides. They could now pin both of Inter’s wing-backs, preventing them attacking Sinkgraven and Bender. The full-backs were now either not pressed or done so at a low tempo by Inter’s 8s. The lower level of pressure helped Leverkusen advance to the final third more consistently. However, they faced many of the same issues as in the first half, unable to prepare moments to play behind Inter’s midfield and support quickly enough to continue attacks.

Leverkusen were still unable to find a consistent solution to defend Inter’s early balls into Lukaku, and the Italians could progress consistently with the same moves as in the first half. In fact, only poor final passes and finishing in the final third prevented them from making the scoreline far more comfortable. Despite the close scoreline, this was a truly one-sided affair, with Conte’s side far too good for their German counterparts. With their compact and aggressive defending and well co-ordinated possession game, it will take a formidable opponent (and perhaps a lot of luck) to stop the Italian giants claiming the Europa league title.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen