Deep Full-Backs in Possession: a Strategic Alternative

As has often been discussed across Spielverlagerung, the flanks generally offer lesser strategic value for the in-possession team. A ball-carrier by the touchline only has 180 degrees of movement and limited access to space across the pitch. Therefore, defensive strategies commonly look to show the opponent towards the outside and into a pressing trap.

A common solution against such pressing schemes has been to drop a midfielder in the first line to create a back three while the full-backs move into high and wide positions. Through having a third player in the first line, the line moves slightly wider and it becomes more difficult for the opponent to apply pressure wide. The weakness of this structure is that it can lead to a lesser presence in the second line and thus central build-up can be difficult. Even if the build-up is able to outplay the opponent’s first line of pressure, the options to play forwards and through the defensive block can be insufficient.

Another solution then, is to build-up with a deep full-back. Compared to the previous solution, having deeper full-backs means that midfielders can stay in the second line and offer themselves as options to break the opponent’s first line of pressure. Further up the field, this means that the wingers typically have to stay wider and this can potentially lead to a lower occupation of space behind the opposition midfield line. Although through effective spacing within the structure, this disadvantage can be reduced.

Particularly against narrow pressing structures, the use of deep full-backs can be an effective means of reducing oppositional pressure by increasing the distance required to shift, as well as reducing oppositional cover through the same means. However, the strategic weaknesses still remain and thus it is imperative that in-possession teams do not keep the ball there too long before the opponent can shift across to close out the space. The ball must either be circulated back inside through the centre-back or deep midfielder, or progressed forwards – either diagonally inside or down the line.

This analysis will discuss how a build-up structure with a deep full-back can be effective against high and midfield presses in reducing oppositional pressure or cover. For some teams, the full-back moves deeper situationally, in reaction to bad build-up play to simply provide the centre-back with an easy passing option. Detailed in the following article will be how the position can be used proactively as part of an in-possession system.

Structural Interaction against Opposition Press

The first section will address the structural implications of the deeper full-back in interaction with an oppositional press depending on the pressing structure of the opposition.

If Opposition Press with Narrow front line (example: winger to centre-back)

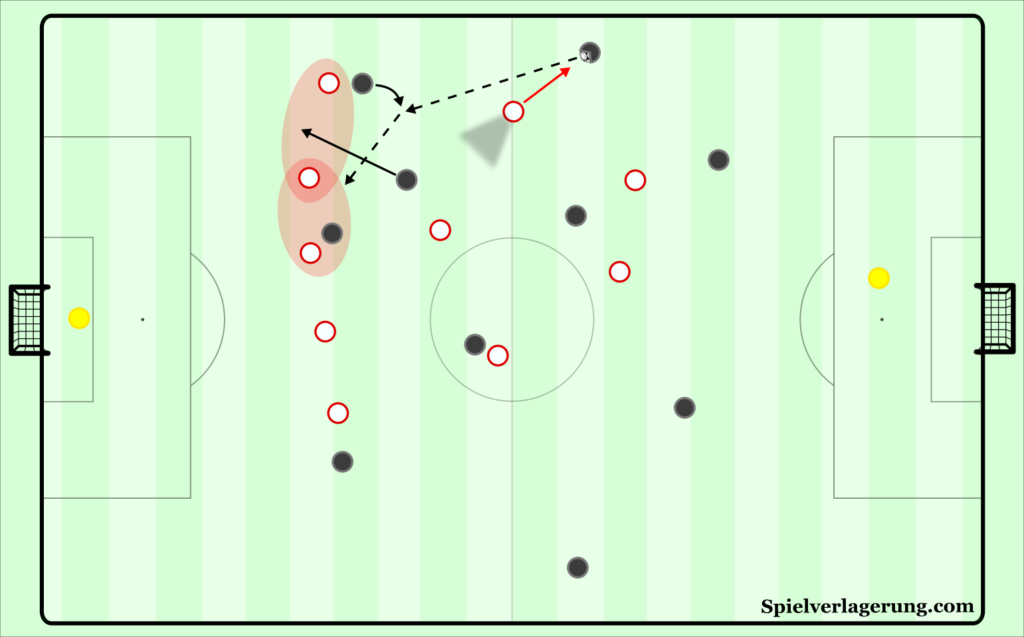

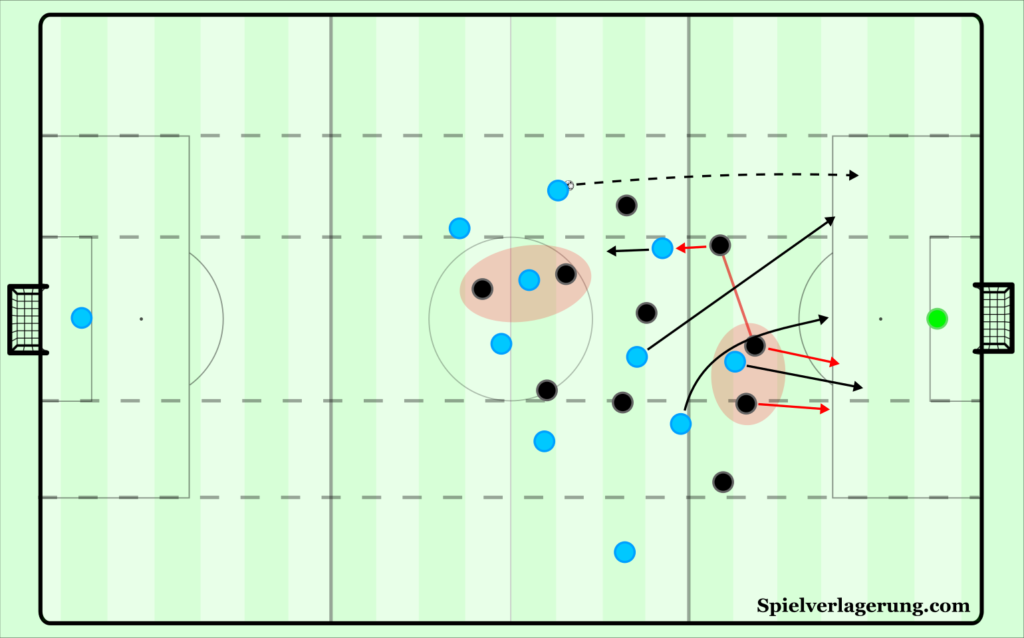

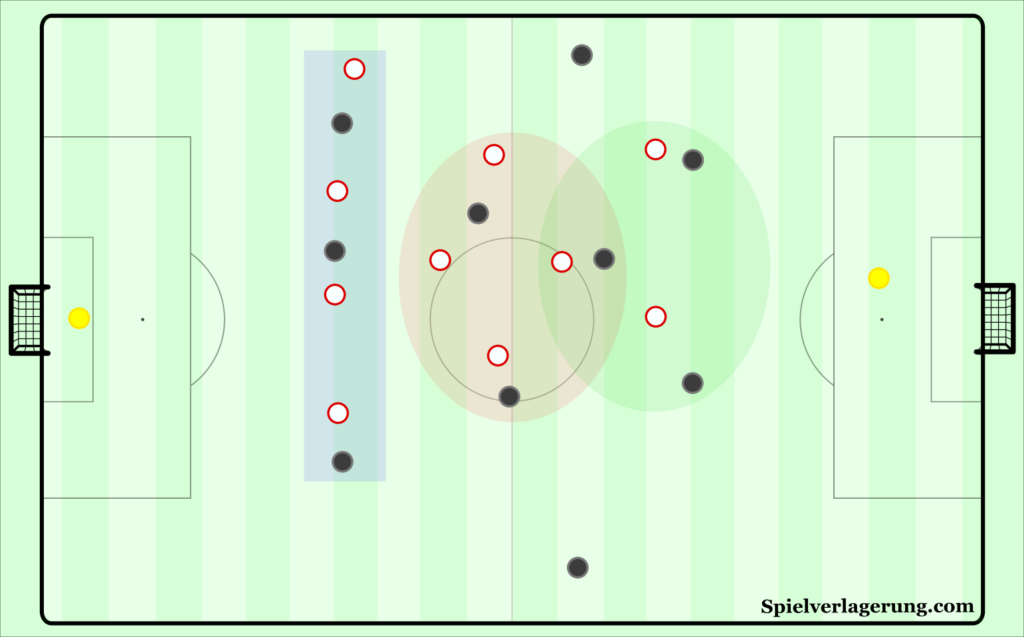

The deeper positioning of the full-back in build-up can be effective to either reduce oppositional pressure or cover against narrow pressing structures. The example discussed in this section will be the common scheme of winger pressing to centre-back, as done by Liverpool.

If the defence presses with a narrow front line, then space is available wider. Through a deeper position, the full-back can then be an option to play directly into, skipping the centre-back who would be pressed by the winger. But moving past the obvious, we can look at the impact of the deep full-back on other players within the build-up structure.

When a winger presses the centre-back in this scheme, they have the intention of keeping the full-back in their cover shadow to stop that passing option, so the winger presses from outside to in. If the full-back is deeper, then the winger must normally press from a wider position and with a bigger arch in his pressing movement if he wants to still cut-off the pass to the full-back. This is of course a longer route to the centre-back and due to the curved trajectory, the run cannot be made at as high of a speed than a straighter-line press.

This longer pressing line consequently gives the centre-back more time on the ball before being pressed, this of course gives them greater time to assess their options but also gives their teammates more time to find positions to offer as a passing option, including the full-back themselves.

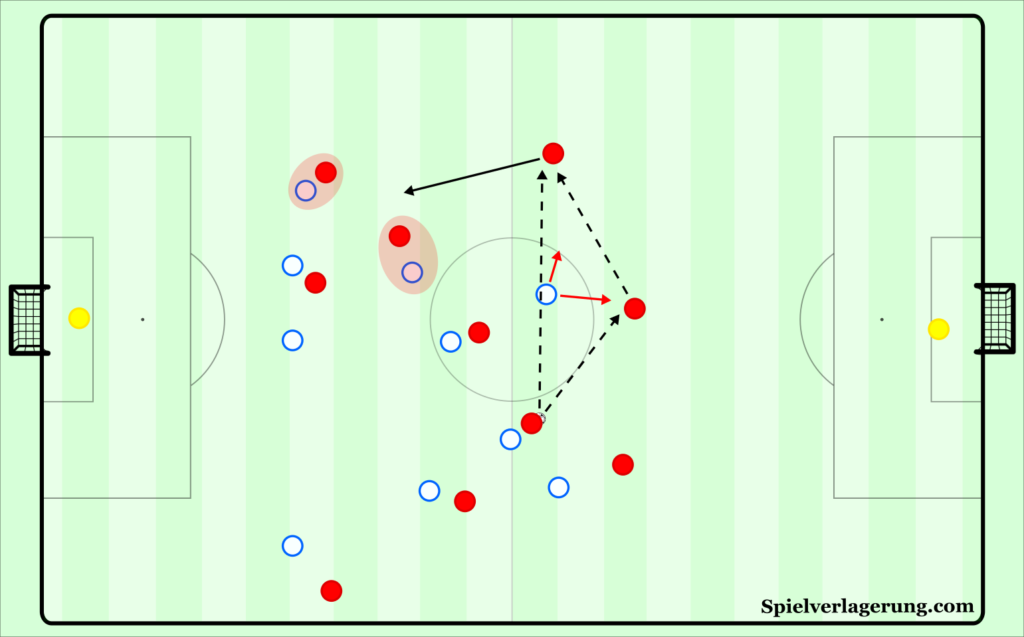

Because the pressure also comes from a wider position, it also offers the possibility for the centre-back to play centrally. This can come in two main forms.

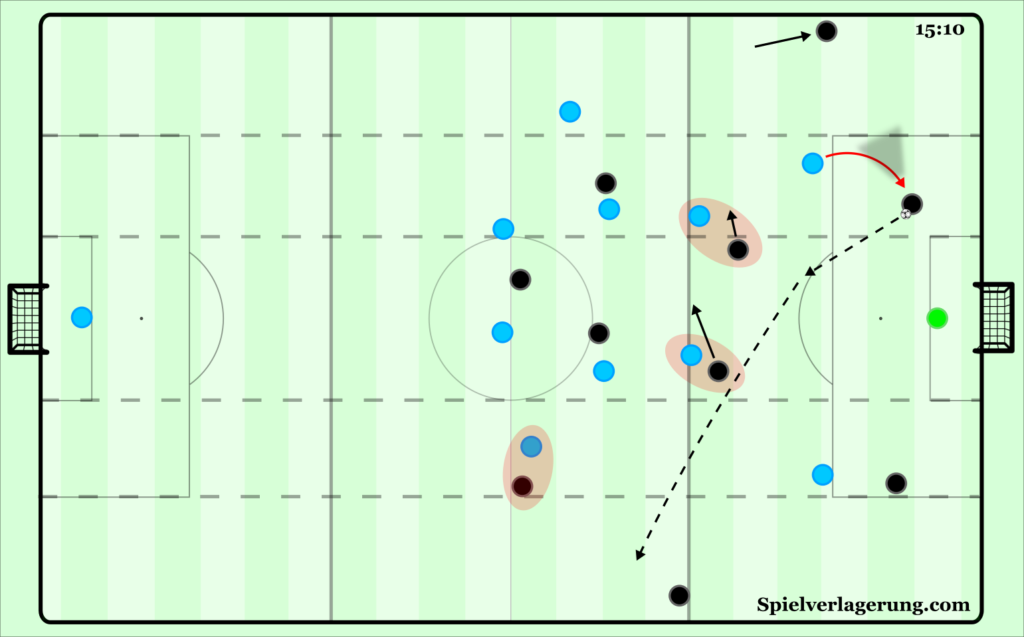

Firstly, the centre-back can step-in with the ball since the space is directly in front of him. Dribbling centrally can be a useful way of creating space by provoking pressure, allowing the centre-back to progress with a longer pass into space further upfield. Also, simply from carrying the ball into a more central position, it means the centre-back can more easily access ball-far spaces, such as making a switch in the example below from Brighton vs Manchester City.

Aside from a dribble, forcing the winger to press from a wider position widens the lane between him and his nearest central midfielder, reducing their coverage of this passing lane. This lane could be occupied by a more advanced central midfielder to create an option to play through the press. From this position, a follow-up action could then be back to the full-back advancing on the blind-side of the pressing winger, or to turn forwards and carry if there is space.

If the full-back receives in this position, it’s unlikely that the winger will be able to recover quickly enough to apply pressure. Therefore, it would be the responsibility of either the opposition central midfielder or full-back to step out and apply pressure. The full-back’s deeper positioning increases the distance for the opponents to step out and could make it too far for them to press at a high intensity. The larger space that they leave behind them as they step out to press could be exploited too. Because of these dilemmas, the majority of teams would sacrifice pressure on the ball and neither position would step out to press, allowing the full-back to carry the ball forwards.

If Opposition Press with Wide front line (example: winger to full-back)

If the opponent press with the winger directly on the full-back, then the deeper positioning is less beneficial. Compared to building up against a narrow pressing structure, the main difference is that the space isn’t immediately with the full-back. Therefore, the position firstly can’t act as an option away from pressure, and as the full-back could be immediately under the pressure, it becomes more difficult to play against the defender. With this now happening deeper within one’s own half, it can cause more problems than it solves.

In this interaction, the movement does not provide greater stability to the build-up. However, it can be used to provoke pressure and reduce oppositional coverage of spaces in midfield or down the outside, assuming the pinning from the front players is effective.

This can create better options for direct build-up from the centre-back, instead of playing into the full-back where he could be pressed. In almost every situation, it is more optimal to avoid playing to the full-back altogether, as they would likely be under high pressure upon receiving with limited options. From the centre-back, the deep positioning can create more direct build-up options, particularly if the winger anticipates the pass wide and steps out early. Through increasing the space inside, the team can increase the margin of error for playing and receiving longer passes, with greater space for follow-up actions (lay-offs, dribbles) to exploit the open structure.

In the example above, Chelsea’s right centre-back plays into Kanté in a similar structure, bypassing Southampton’s first line of pressure. Although Kanté receives with pressure from behind, he has so much space to his left and right that he is able to take a safe touch and dribble around his defender, without a big threat of losing the ball.

Opposite Full-Back

As a smaller side-note, the deep positioning of the ball-far full-back can be another way of quickly diffusing pressure as an easy out-ball. The main issue here, however, is the distance of the pass to reach them. Because of this, it can be dangerous if the defenders are able to reach the full-back by the time they receive the ball. Therefore, it may not be very effective against wide defensive structures and relies to a large extent on pinning actions by other ball-far players to give the full-back time to receive the longer pass.

Creating the Structure with an Asymmetrical Back Five

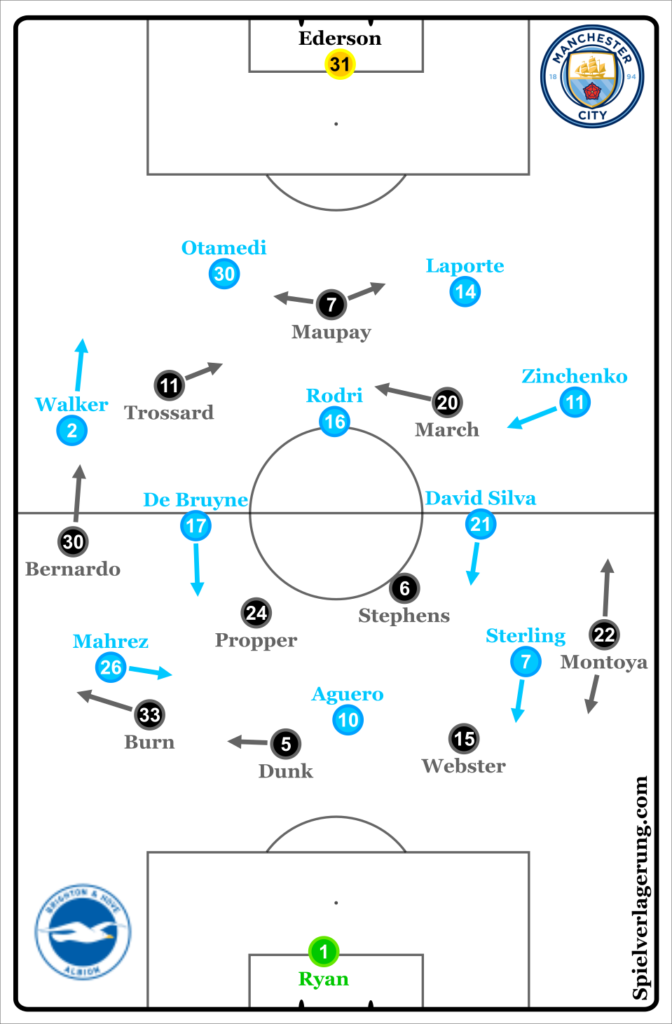

The majority of this analysis is focused on structures with a base back four, however Brighton under Graham Potter have created a similar build-up structure with a back five this season. Against Manchester City, for example, they moved their left wing-back Bernardo into a left wing position, while the left centre-back essentially became a deep full-back in possession. On the right, Montoya acted more as a typical full-back.

Effect of New Goal-Kick Rules

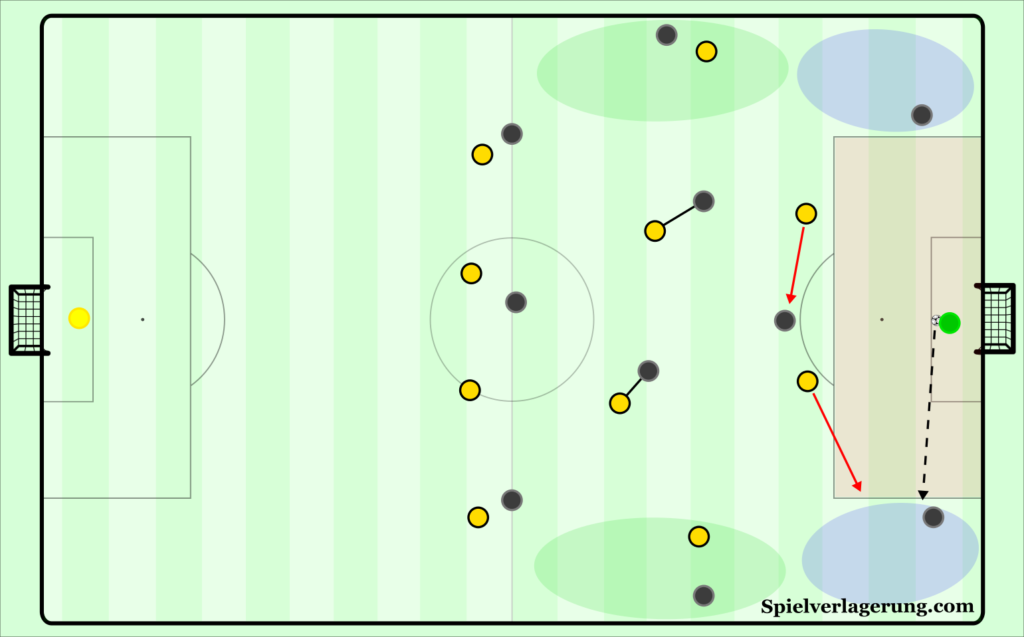

The new goal-kick rules implemented largely at the beginning of this season have had a significant effect on teams’ build-up from their first third. Ultimately, through allowing players to receive from the goalkeeper inside the penalty area, the rule allows the in-possession team to a) reduce oppositional pressure by increasing the distance the defender must travel and b) immediately use the full extent of the first third, without the penalty box essentially becoming active after the first pass. To take advantage, it has been common that centre-backs receive in deeper and more inside positions than previously.

Of course, this then has a knock-on impact on other players’ positioning within the structure, including the full-backs. Previously, as deep centre-backs had to be at least as wide as the penalty area, it would be rare that full-backs would drop as they would be occupying the same space. Instead, it was more often that they would stay roughly on the height between the first and second thirds of the pitch. Now, since the centre-backs can receive inside the box, the full-backs can move deeper into open space to remain playable through the angle and distance to their teammates.

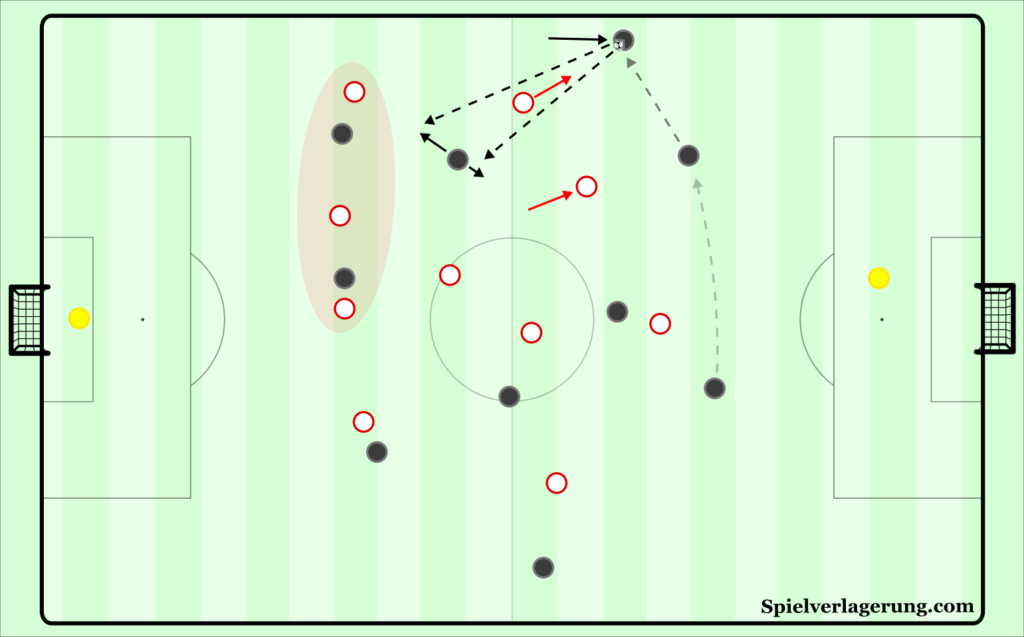

Above is a goal-kick structure from Sassuolo. They very rarely play to the deep full-backs, unlike Napoli or Roma, but instead look to draw out the opposition midfield line along with the deep positioning of the pivots. The main intention of this is to maximise the space in front of the opponent back four to play more direct, flat passes into. The above is an example from an encounter against Napoli.

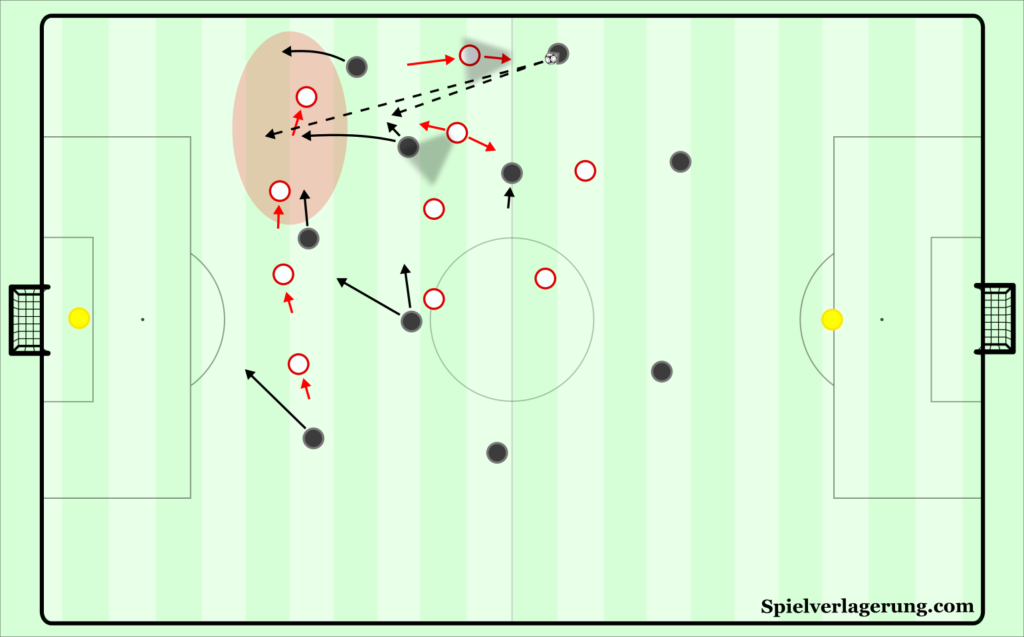

Against a Midfield Press

As against a high press, using deep full-backs are an effective way of reducing oppositional cover or pressure against narrow defensive structures. The primary example within this section will be on a common formation match-up within the Premier League this season – a 4-3-3 against a 5-3-2 midfield press. Again, without a winger starting closer to the full-back to directly attack him, this position can be an effective way of reducing oppositional pressure. Then, if the opponent still attempts a press, not only will it typically be at a lower intensity but the greater distance to shift increases the possibility of spaces opening up inside to exploit.

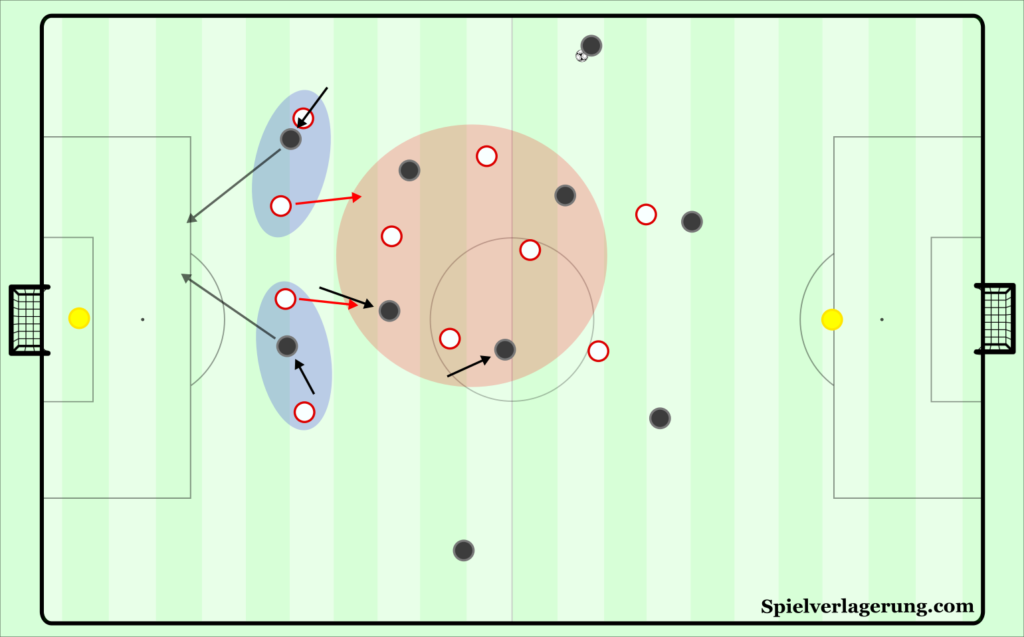

With a deep full-back against a 5-3-2, there are two main possibilities which happen – either the ball-near central midfielder steps out or the wing-back moves up to press.

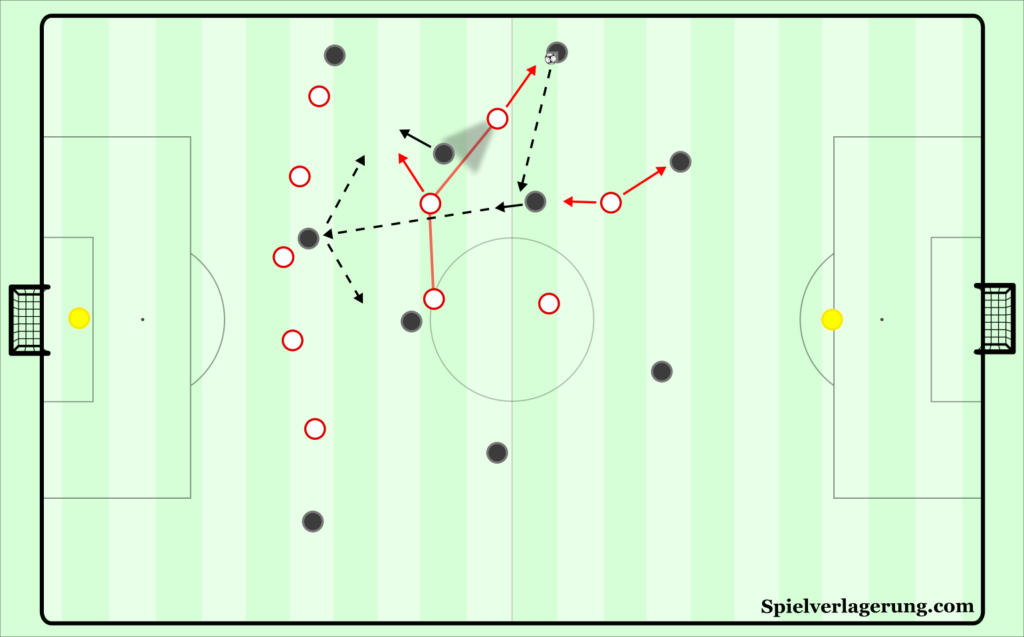

If Eight Steps Out

If it’s the responsibility of the central midfielder to step out, then the defensive midfield line is open to losing horizontal compactness, depending on how well the opponent shift across as a team. If the middle central midfielder does not shift across sufficiently, then it’s possible to play on the first midfielder’s blind-side. If he does shift sufficiently, then it could still be possible to play across into the centre as shown in the instance with Liverpool below.

Naturally, it’s important to consider the follow-up actions for the player receiving inside. They are almost always going to be receiving while facing towards the touchline, but with forward momentum and in a good position to shield the ball from pressure from inside or on their back. Because they have a poor body position to see progressive options inside, the clearest penetrative pass they could likely make would be outside to the winger, either in-behind the defensive line or to feet to create a one vs one.

If that option is less feasible, then it becomes imperative to try and continue the ball’s progression diagonally into the centre of the pitch, or the defence would be able to shift across and press the attack out to the touchline. Given the likely angle of pressure from inside, this task can be quite difficult to achieve individually, so we will focus on the actions of supporting players to try and enable this continuation inside. There could be a number of solutions, depending on context and player profiles.

Integration of the centre-forward as a ‘wall’ player to receive and layoff to a more central player could allow access into the space in front of the defensive line with the next receiver facing forwards. However, the timing of this combination has a small margin of error if the defensive line has three centre-backs, meaning the defender could aggressively press the centre-forward from behind.

If the winger comes short to receive to feet, then the ball moves back towards the touchline, but the winger can have a good body position to play back inside. If they curve their run inside to receive, then it’s possible that they will be looking directly infield, making it possible to find inside options – made easier to play to if their stronger foot is ‘inverted’.

More dependent on the players’ capabilities, but another option would be for the full-back to immediately move inside to then offer for a return pass. Like the winger, he would receive with a field of view overlooking possible options inside and have the power of counterdynamic behind him. If his initial presser had to step-out quickly to attack him, then the opponent would struggle to decelerate and change his direction to then stay with the full-back if he moves in the opposite direction inside.

Solving the Pressure

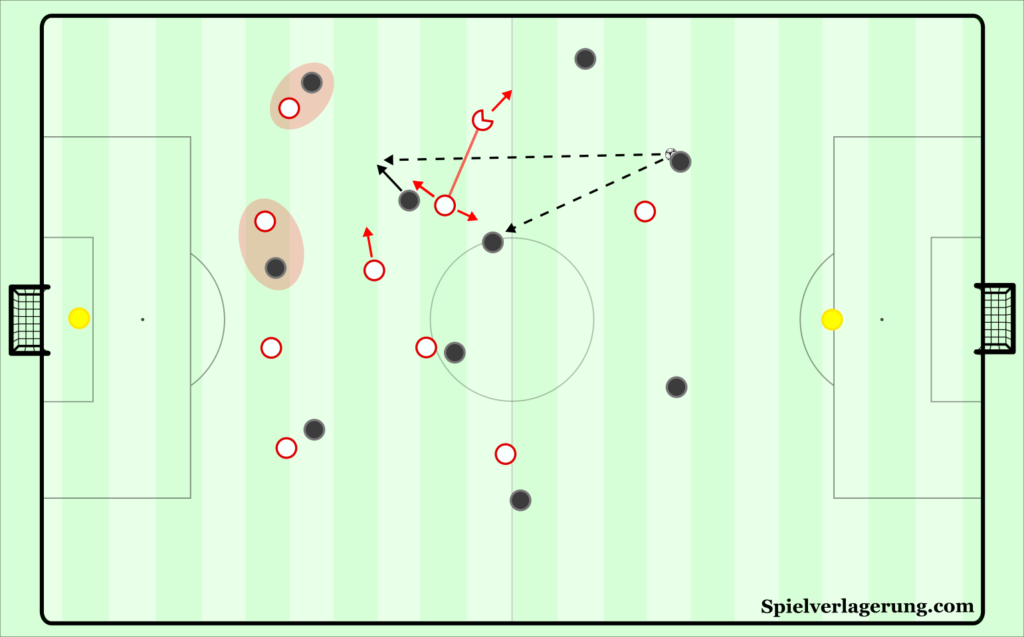

Before moving onto discussing the progressing options if the wing-back is the presser, I want to discuss in more detail the act of playing against the presser from individual and group tactical levels. As has been discussed in the introduction, it can be more difficult to play against the pressure effectively due to the constraints of the wide space. However, the context in which they face pressure is quite consistent compared to more central positions and as a result a decision-making framework can be created to aid the full-back in playing against an oncoming presser from inside the pitch.

Positional Level

First and foremost, we will discuss the importance of increasing passing options available. As a general rule, having a greater number of passing options when well-spaced both reduces the opposition’s ability to press as well as their ability to cover said options.

It reduces the opposition’s ability to cover passing lanes simply because there are a greater number of options to screen. This in turn reduces their ability to apply pressure, because they must first be in position to screen these options before attacking the ball-carrier (and would do so with fewer players), or else they would simply be bypassed. So, the question is, how can these options be created within a positional structure? We will approach it by each position group.

Centre-Back

The ball-near central defender must drop as quickly as possible and as deep as necessary in order to be a backwards option away from the pressure. They must drop quickly to create the option early but be able to adjust out of a backwards-pressing cover shadow if needed. They must only drop as deep as necessary to give themselves space to turn out and circulate across the pitch.

Central Midfield

The key positioning in this interaction is the spacing of the two ball-near central midfielders. The most important factor is that they occupy different heights on the pitch, something which normally happens naturally in most formations (i.e. pivot and central midfielder in a 4-3-3). This is key so that they occupy two different passing lanes and thus do not block passes into each other. Ideally, they should offer as options in front of the presser as well as behind them to restrict the presser’s ability to apply pressure while covering the space behind him.

Because more specific follow-up actions have been, and will be discussed within the analysis itself, I will not go into detail of the options for each position. However, it remains a key consideration for the positioning and orientation of the players looking to receive.

Winger

The winger’s role in this interaction is mainly to pin the opposition full-back to maximise space between the lines. This is a key action to maximise the space available behind the pressing player, to stop the defending full-back from moving up to close the space left. They can still act as an option to receive in-behind the defensive line or to feet, depending on player profile.

If they receive to feet, it would be ideal that they receive the ball on an angle, as opposed to straight into him where he could be pressed easier. They would also have a better body position to find options inside or turn and dribble inside themselves. Since he would often receive with a limited direction to play in, lay-off options inside from the central midfielders are crucial. If the ball-near central midfielder is offering themselves on the blind-side of the full-back’s presser, then they would naturally be in a good position to receive the lay-off.

Another means of supporting the winger receiving to feet in this situation is to dynamically pin the full-back who would challenge him. This could be done by the centre-forward moving wide, or the central midfielder moving in-behind. Chelsea perform this action fairly well through Mason Mount moving in-behind the full-back, allowing the winger to receive in slightly more space and move inside. The sacrifice you make with either of these positions pinning the defender, is that they are less available then for follow-up actions to move the ball inside, although the winger dribbling inside themselves becomes more feasible.

Through effective spacing by the ball-near players, they can create a five vs three situation to outplay pressure, with the emphasis on occupying four different heights to reduce the opposition’s ability to cover all options.

Isolating the Interaction Between Full-Back, Ball-Near Central Midfielder and Presser

To begin, it must be said that football cannot fully be described by isolating certain positions in how they interact. This is because the context of many other players affects the decision-making of each player. However, for the purpose of communicating the analysis, this is the approach I will take.

The two main factors which will be discussed within this short section are

- taking reference of the opponent’s angle of press

- the positioning of the ball-near central midfielder.

A third point will be how momentum can favour the full-back through the use of ‘counterdynamic’.

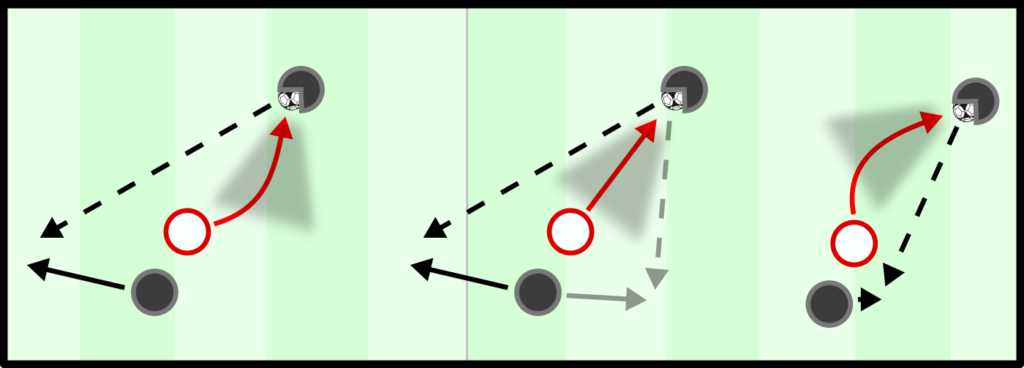

Defenders mainly approach the full-back in three manners.

- Approach the full-back while adjusting their movement to cover inside passing lanes and show the full-back down the line.

- Approach the full-back while adjusting their movement to cover an outside passing option and show them inside.

- They directly approach the full-back. Here they have the shortest path to the player on the ball and can engage him the earliest but leave passing lanes more exposed.

It should be always noted when discussing hypothetical situations – we should not assume that the defender makes the optimal decision every time.

In all three cases, the defender communicates a key message to not only the full-back, but his teammates looking to act as passing options in how they should solve the situation. If the full-back’s decision is based on the defender’s pressing angle, it follows that the optimal starting position for ball-near teammates is one that allows them to adjust their positioning in a similar manner. This entails them being in a position where they can:

1. Move deeper to receive in front of the pressing defender.

Although the less progressive option, it is important to be able to move in front to be a safe option if the pressure becomes too high on the full-back. With such a movement, the player would receive the ball with his back to goal, making it difficult to play forwards but also allowing him to shield the ball against pressure. The movement of the centre-backs (to move out of the cover shadow of any backwards-pressing forwards) and the pivot then become important to free themselves as passing options so the team can circulate the ball out of pressure.

With an optimal spacing, this option should also be occupied already by a deeper midfielder – however they may not always be available due to their positioning or oppositional cover.

2. Move higher to receive behind the pressing defender and progress the attack.

The more progressive option, allowing the full-back to bypass opponents with a pass and accelerate the attack forwards. Opposite to option a), the player would likely receive facing and moving forwards (albeit still somewhat facing outside). Typically, then facing pressure from inside (formation dependent, but typically from a pivot), it is important for him to then have a follow-up option from a wide forward, or a connecting player to continue the attack inside. To reduce pressure from elsewhere, the role of the wide forward is important in pinning the opposition centre-back and full-back.

To be able to perform either movement, the player should normally have a starting position on the blindside of the defender and usually ‘on’ the line (i.e. the midfield line) of the presser. He allows himself to be marked, then dis-marks through blind-side movement. The timing of the movement is of utmost importance. They cannot move too early that the defender can adjust their own press to block the option. They cannot move too late that they simply don’t become free in-time for the full-back to make the pass.

Of course, the option that we have not discussed for the full-back is indeed dribbling against the defender. This is also a viable means of beating the individual presser, if the passing option is marked but the space is still available. The same idea in relation to playing against the angle of press still applies, and such is a situation where the ball-carrier can use the law of momentum in his favour through the use of counter-dynamic. With regards to follow-up actions, the dribble could then create a free teammate higher up by attracting the next defender, especially if the opponent is particularly man-oriented.

We can summarise these options through simple instructions for each position

Full-Back

- If the winger closes an option, then play to the space they open

- If they attack you directly, then play behind them

- If the winger closes an option but your teammate is marked, then dribble into the space they open

- Once you’ve played past the defender, make yourself a passing option on their blind-side to progress or retain

Central Midfielder

- If the full-back has the ball, then position yourself diagonally higher to them and on the blindside of their presser.

- If the winger closes an option, move to the space they open

- If the pressure on the full-back is high and your pivot isn’t asking inside, move in front of the presser to receive safe side

- Follow-up options would be playing backwards to centre-backs, or turning out to find pivot / ball-far central midfielder

- If pressure is not too high, ask to receive beyond the presser to break the opponent midfield line

- Follow-up options would be to find the winger to feet or in-behind, play into the centre-forward or dribble against your presser from inside

- If pressure is not too high but winger is available, move forwards and make yourself available for layoff from winger or pin the defending full-back.

Counterdynamic

In a One vs One

A difference of dribbling in a situation of being pressed compared to a typical one vs one is the momentum of the defender – in that he more directly approaches the full-back at a higher speed. While this poses a different threat to the ball-carrier, with greater urgency required in his decision making, it can also make it easier to dribble past the defender as he is unable to change direction as immediately.

With a deeper starting position, the full-back can increase the initial distance to his opponent, thus requiring him to press at a greater speed. This then can accentuate the effect of counterdynamic and aid the full-back in beating him in a dribble. It also means that he is less able to achieve both applying sufficient pressure on the ball at the same time as using his cover shadow to protect inside lanes.

But of course, this does not only apply in a dribbling situation and is also pertinent when passing behind defenders and on a group-tactical level too. If the defender must sprint to get pressure on the full-back, he will be physically less able to be able to intercept passes to the sides of him. A similar concept can also be related to the other shifting defenders.

Group-Tactical

When the ball goes out to a deep full-back from the centre-back, the defence begins to shift towards the ball in a mainly horizontal direction. Through doing so, they can allow spaces to open up in ball-far areas (again we must assume that not every player shifts perfectly). Similarly to my point on the effect of speed in a 1v1, if the team collectively have to shift at a higher intensity then spaces are more likely to open up due to the greater difficulty in coordinating the movements. Due to pressure on the ball, these spaces may not be immediately accessible for the full-back but could be open to play through into once the immediate pressure on the wing is solved and the ball has been played inside into the half-space.

Furthermore, as they move in one direction, through the law of momentum it becomes more difficult to react to passes travelling past the side they are moving from. To explain that more literally, if the midfielder is moving to their left, then it becomes more difficult to intercept passes going past their right. So not only does the space become greater on a geometrical level, but it also becomes more difficult to intercept the passes going into the space.

This is a key reason why diagonal passes against the shifting of the pressing are so valuable and is also a reason why such passes from the deep full-back position can be dangerous. Inherently these passes can attack the blind-side of shifting defenders, allow a team to quickly move the ball from a less dangerous position into one where many threatening options are available.

Now… if it’s instead the wing-back who presses.

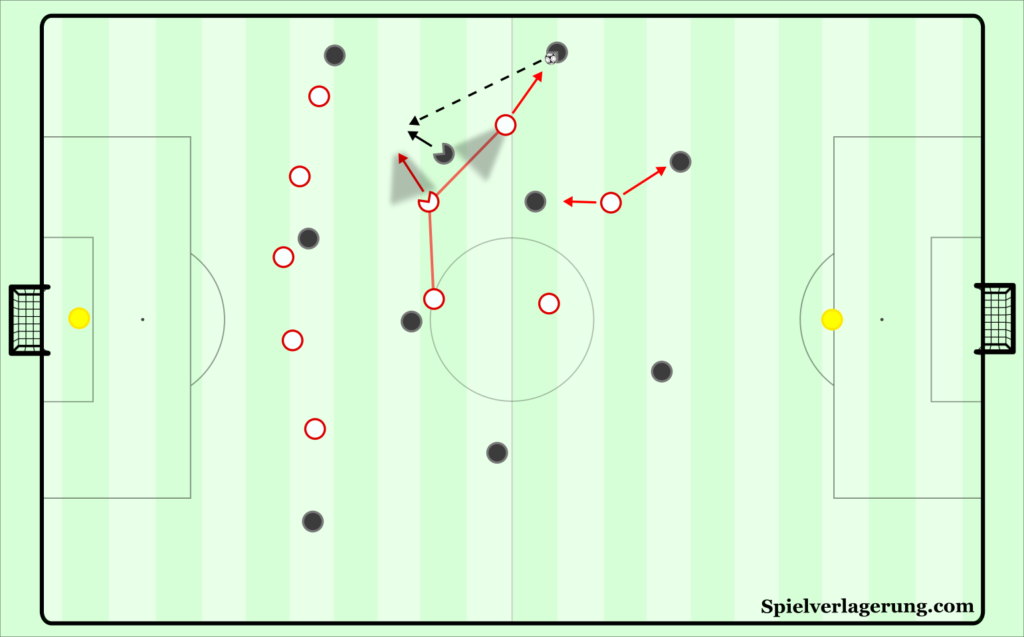

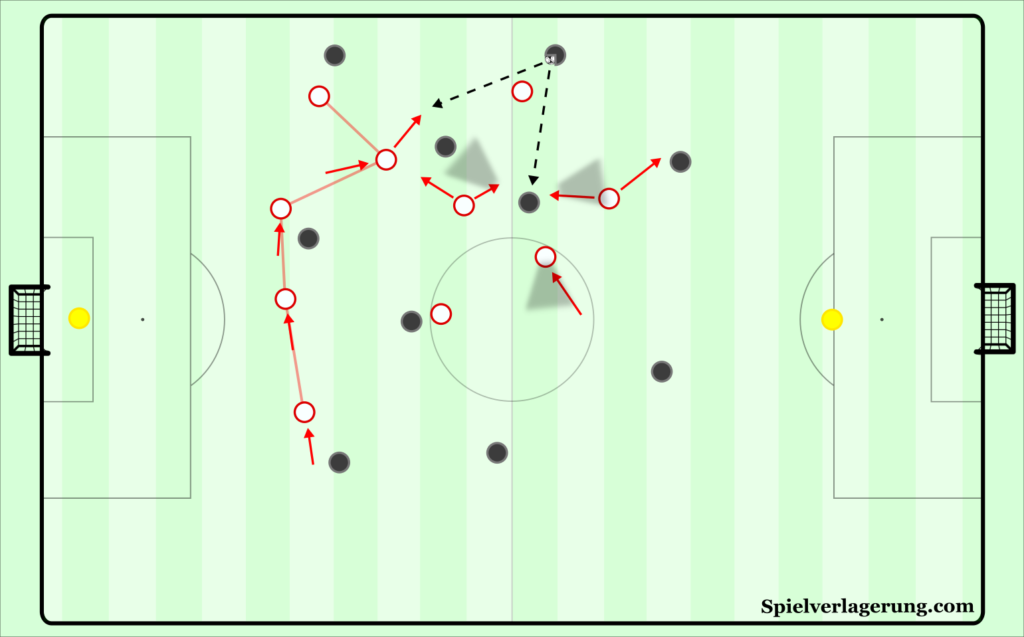

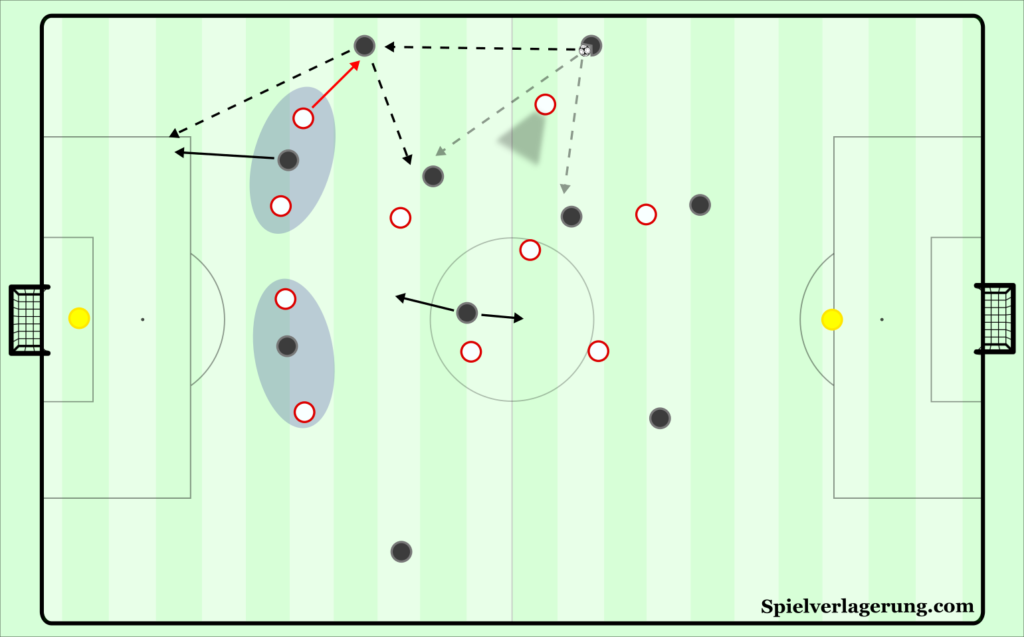

If Wing-Back Steps Out

If the defending wing-back steps out to press, a key difference is that their angle of approach is vertically along the touchline as opposed to diagonally from inside. This means that the engaging defender is not simultaneously covering passing lanes inside into the half-space. Although of course the inside midfielders would have the role of screening passes, it could make it easier for the full-back to find lanes. This is because he is able to carry the ball facing inwards (without having to protect the ball with his body shape) and their view inside the field is less obstructed without a defender in their face.

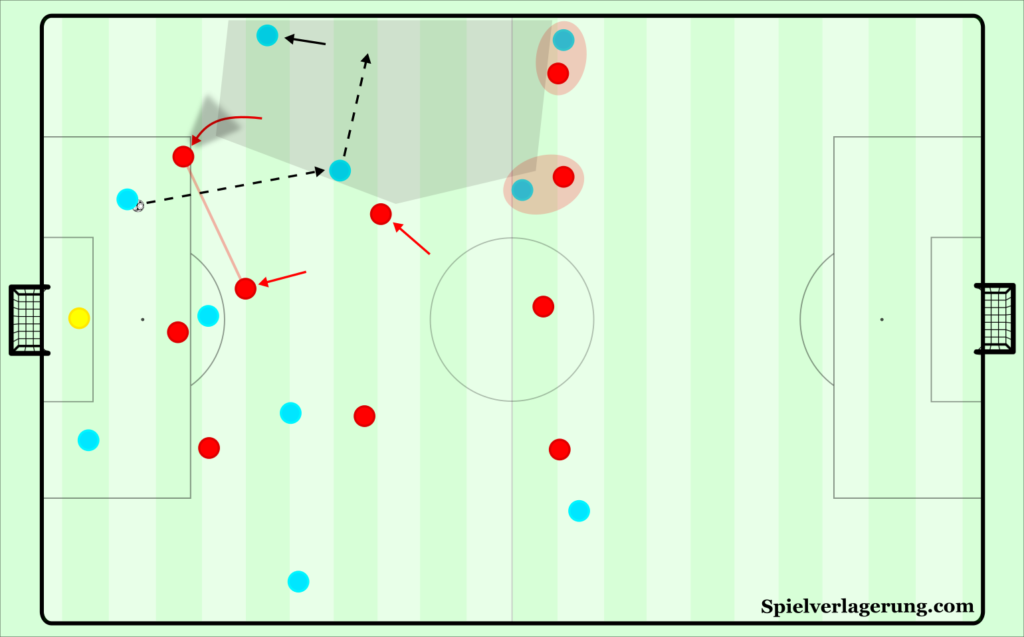

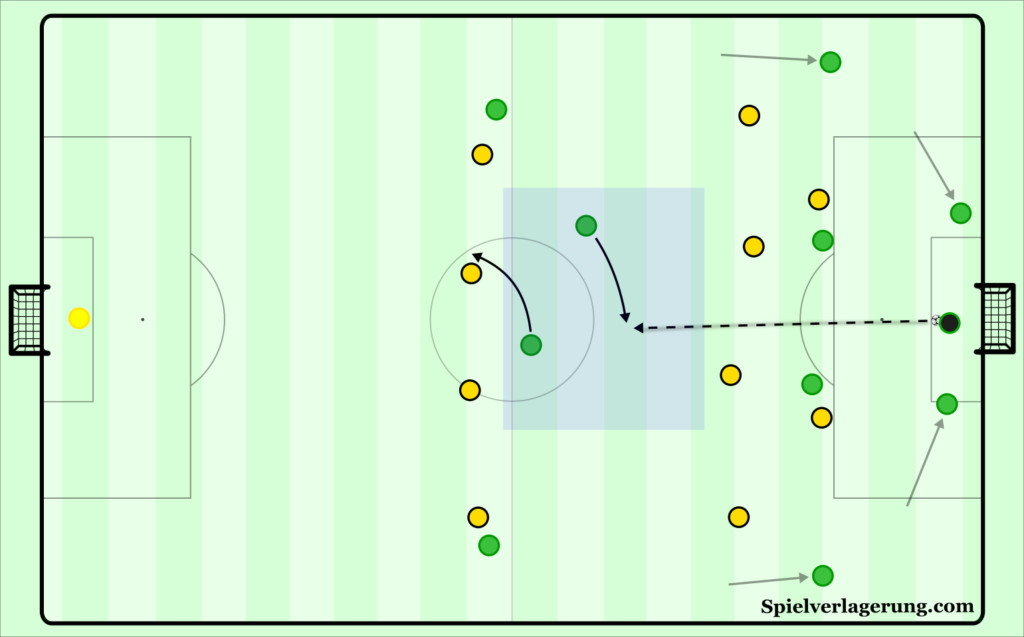

While the midfield line is susceptible to being stretched when the midfielder steps out, the defensive line has to shift across if the wing-back presses to ensure the channel isn’t completely open. Therefore, it is more likely that space is available between defenders in the last line. This is a situation that Liverpool create well through the deep full-backs in their 4-3-3. If they can force the wing-back out to press their full-back, as shown in this scene below, then they can create a three vs three against the opponents’ last line with their winger, centre-forward and an advancing central midfielder.

Through playing directly in front of the last line, of course you progress your team closer to the opposition goal – great. The context of receiving is slightly different too. When receiving slightly deeper in midfield, the pressure if more likely to be on the outside – but if you receive higher, the pressure is more likely to be from behind – making it easier to open up after receiving and be able to see options further infield.

However, the action of receiving the ball itself could become more difficult from a momentum / orientation perspective. The ball is now received more over the shoulder with the receiver running onto it, as opposed to receiving more ‘to feet’ in a deeper position. This could be more difficult to control at high speeds without the ball going too far in front of you, although shouldn’t be a problem at elite level.

By forcing the last line to shift, gaps can also be created to simply play directly in-behind, as Manchester City did for their early first goal against Brighton in August.

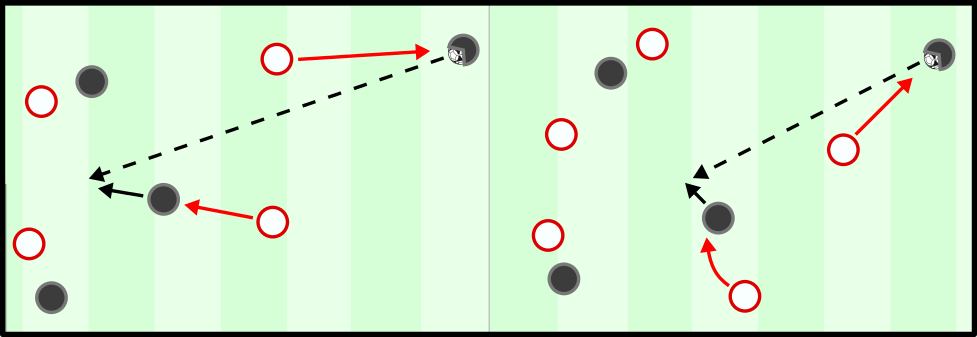

Against Winger

Deep full-backs can also be effective against midfield presses with a winger starting from a position on the midfield line. Because they begin from a narrower position, the full-back can receive and have time to act against the pressure, albeit with slightly less time than against a central midfielder or wing-back. Given that the narrow starting position of the winger is important to the effectiveness of the structure, a way to increase the likelihood of success is to attempt these progressions following switches across the first line, where the winger would have a narrow covering position when initially ball-far.

Compared to prior analysis based on the interaction against a 5-3-2, many similar dynamics are consistent against a winger pressing, including the options to play against the pressure. Like this interaction has been a common theme in match-ups between a 4-3-3 against a 5-3-2 this season, it has also been a common way for teams to progress against a 4-1-4-1.

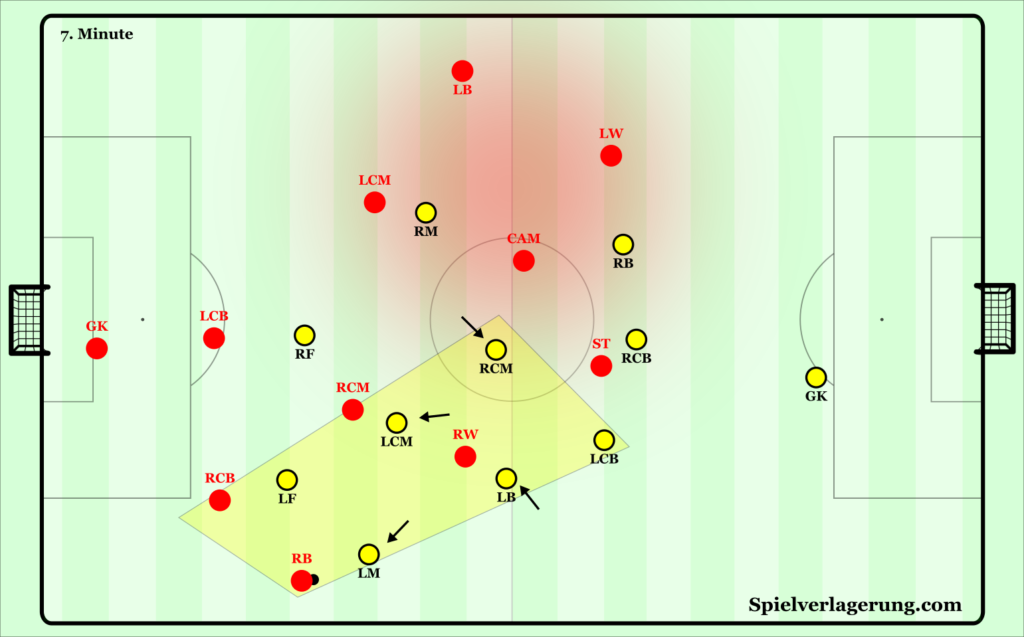

With the winger pinning the ball-near defending full-back and centre-back and the defending winger stepping up to the in-possession full-back, teams can stretch the distance between the two players vertically. Many 4-1-4-1 midfield presses entail the ball-near central midfielder stepping up to the on-the-ball centre-back, if the in-possession team are able to draw the centre-forward to the other side of the pitch. With them stepping up along with the winger, it can create a space which is too big for the pivot to shift across and cover. This space has been a considerable weak point of teams such as Manchester City, AFC Bournemouth, and West Ham in recent years, who all defend in a 4-1-4-1 with a central midfielder moving higher.

Another key difference to the 5-3-2 is the implication of a four-man defence (we’ll say the 5-4-1 doesn’t exist for now…). By increasing the distance between winger and full-back, it becomes more possible to create one vs one opportunities for your winger, since the full-back is less likely to get support from his own winger. Against a five-man defence, this is less feasible as the defending full-back will receive more support from the ball-near wide centre-back.

This is something that Manchester City do well, with Kyle Walker deeper and Riyad Mahrez up against the defender, as well as the Netherlands Women Team with Desiree van Lunteren and Shanice van de Sanden (with Jackie Groenen finding space between them).

A deep full-back also increases the chances of the defending winger jumping too early and opening the passing lane inside before the centre-back has made the decision to play the ball. This is particularly an issue in 4-1-4-1 presses where the ball-near central midfielder steps up to engage the centre-back, leaving far too much space for the lone pivot to cover. In such a case, the full-back reduces oppositional cover by provoking the defender without receiving the ball, opening the passing lane for the centre-back.

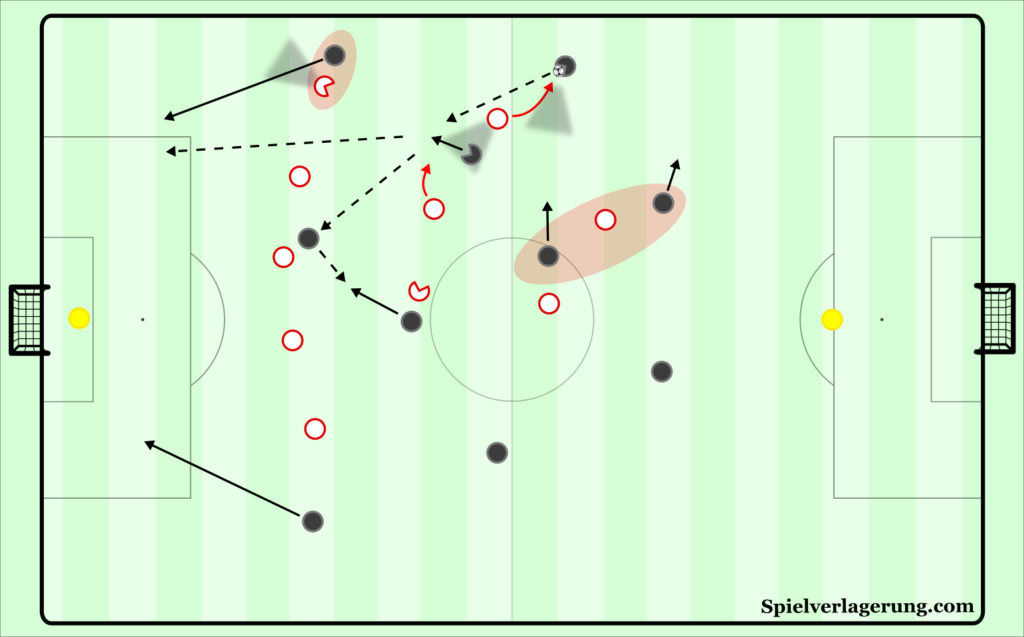

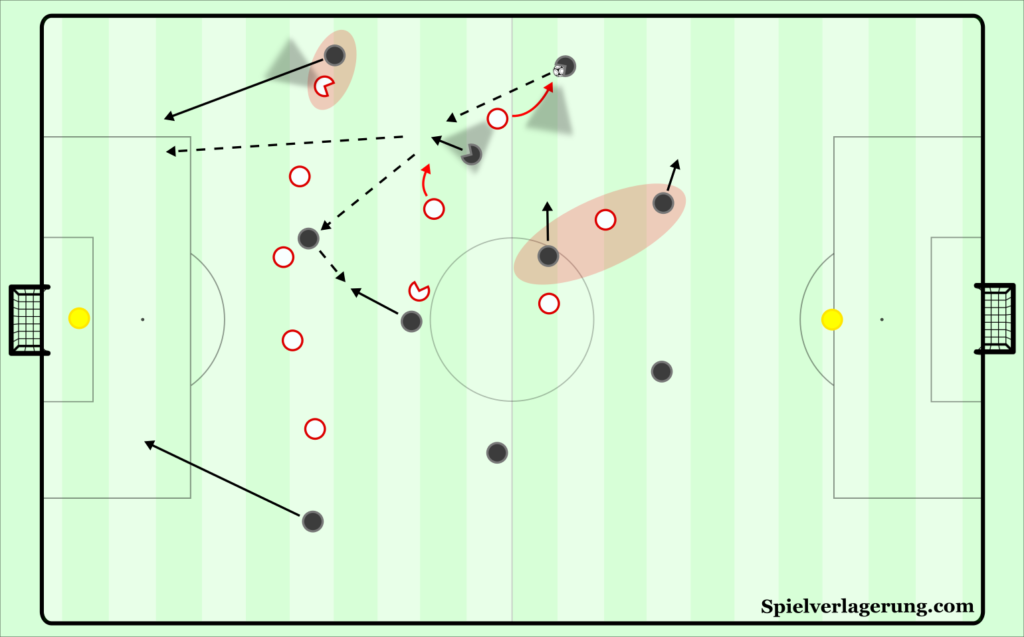

Possible Solution for Out of Possession Teams Defending in 5-3-2

For teams defending in a 5-3-2, this is the main ‘problem’ space for the reasons discussed in this article. How then, can teams adjust to minimise this weakness? The first point to be made is of course, there can be no adaption that solves an issue without making sacrifices elsewhere, or else football would be an awful game.

As discussed, the main issue with the 5-3-2 against a deep full-back is that the distance is too large to apply pressure effectively without significantly reducing cover behind.

Therefore, structurally an adaptation should allow the presser to engage with greater intensity without as big of a concern of being bypassed with ease. This would be done by:

- Allowing for a slightly wider starting position, facilitated by…

- Increasing cover behind the defender, which also allows them to attack the full-back at a higher speed

When looking at the base formation, the most cover is in the last line and thus it makes sense for cover to be reduced there to increase it in front. As shown in the diagram, this is done with the centre-back stepping up to the ball-near central midfielder. This movement changes the structure to resemble more of a 4-diamond-2.

From this position, the centre-back can immediately pressure any passes which are played behind the stepping-out central midfielder, while the middle midfielder can then backwards press and screen any options inside if the opponent make that pass. With a centre-back there to press those passes, the middle midfielder can then be more oriented towards attacking any passes into the pivot, along with the two centre-forwards to trap him from three angles.

As cover is reduced in the last line, this is the space that ultimately becomes more vulnerable, and the team must be prepared to defend these situations accordingly.

Against a 4-Diamond-2

Although it has been a common formation match-up this season, explaining this tactical concept purely through the lens of a 4-3-3 against a 5-3-2 feels rather disingenuous. In such a situation, five defenders are pinned by three attackers and thus the in-possession have two free players to use in midfield or the first line. So instead, I will talk about the differences compared to when defending against a 4-diamond-2 and how the in-possession team can play against that. I have chosen this formation since it’s a common narrow shape but again, with one less player covering in the last line and one more in midfield.

Against a standard 4-3-3, the 4-diamond-2 is well-suited to defend. They have an extra player security in the first line (four defenders vs three attackers), four midfielders (on at least three different lines, usually) against three midfielders, with two players higher to restrict switches without playing back to the goalkeeper.

Therefore, it’s likely that the 4-3-3 needs to be adapted to address these issues while also creating structural dilemmas for the out of possession team.

Pinning the Back Four with Two Attackers

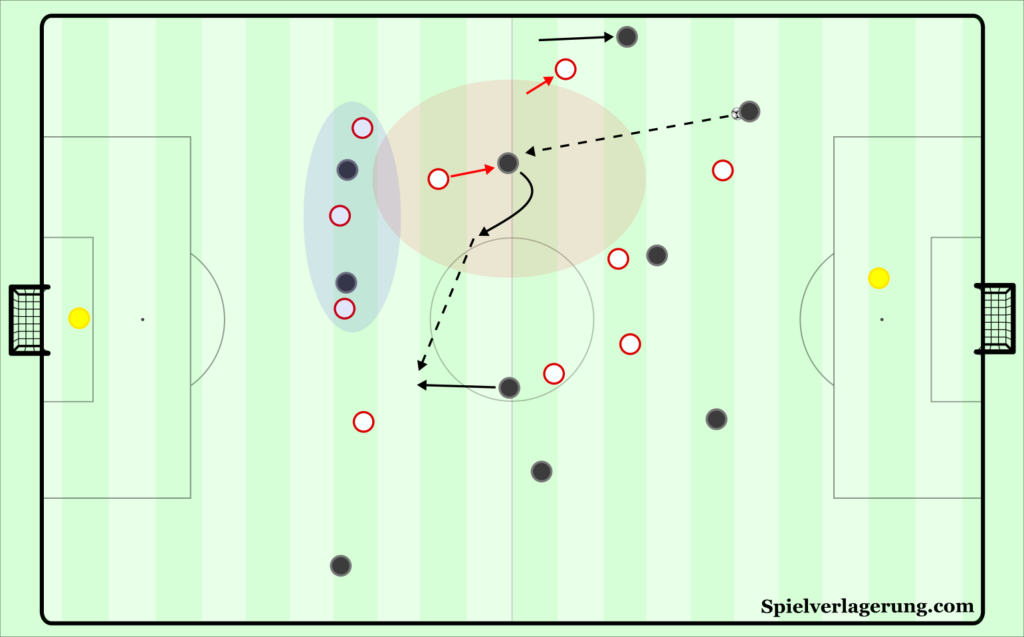

The most immediate solution would be to adjust the front of the structure, to now pin the opponents’ back four with two players, while one attacker would move into a different position. The first example could be with the centre-forward dropping onto one line deeper, with the wingers moving inside. This would result in four central players acting against the four central players of the diamond, where options to play through can be created through dismarking actions (including integration of the full-back on the ball, since the ball-near opposition midfielder would have to press).

With such a structure, the explicit number of options available to the full-back doesn’t necessarily increase. Into midfield, there are still only the two immediate options of the higher and deeper midfielders. However, with the additional player there comes greater flexibility of those options.

The higher midfielder could potentially move wider to receive or effect the pressing line of the defending midfielder, as well as creating space for the ball-far higher central midfielder to move into. The second player on this line could also perform a pinning role on the diamond’s deepest midfielder, allowing the ball-near midfielder to receive in more space.

The deeper ball-near midfielder also has more flexibility since they have a second midfielder on their line, where they could move wider or drop outside the shape to offer security if necessary. With the two pinning inside wingers, it becomes extremely difficult for the two centre-backs to step out to regain numerical superiority in midfield, as either would leave space in-behind.

Another, less stable adaptation could be to make the front three lopsided, with the ball-near winger moving outside and slightly deeper, the centre-forward moving ball-near to pin the opponent full-back and centre-back, and the ball-far winger inside to pin the other two. Again, the four defenders are pinned with two attackers and the additional player is now on the outside of the shape instead of a fourth central player.

Compared to the 4-2-2-2, this -does- give the full-back with an additional option to play to immediately, with the ball-near winger now being more of a passing option than a pinning player (as the full-back would be pinned by the centre-forward). With an outside passing option, the full-back and the team have more flexibility of how to play the situation instead of just having two inside options. The outside option can also act as another method of playing diagonally into space inside, as the team can change the angle of lanes inside to try and bypass the pressing midfielder.

Full-Back Role in the Final Third

Naturally, this deeper positioning in the build-up could mean that full-backs have less direct attacking involvement in the final third due to the distance required to move up. The exception we see sometimes is the abnormal pace of Kyle Walker when he overlaps his winger from a deep starting point. This gives him an advantage over his defender due to the speed he is able to generate from the run but is only achievable in the first place due to his physical capacity.

Instead then, it’s more feasible for full-backs to adopt roles more based on supporting circulation around the low block and providing security in rest-defence for transitional moments. While they operate in deeper positions, this could actually benefit the winger by restricting the defending winger from doubling-up with his full-back, making it easier to create one vs one situations. Again, this is a strength of Manchester City and particularly on their right side. The full-backs can also occupy positions to make half-space crosses behind the defensive line, too – again a strength of Manchester City but also Tottenham under Pochettino, while Alexander-Arnold is effective at crossing from such positions too.

Conclusion

Although the wide deep spaces can be strategically weak in build-up, they can be used to reduce or outplay an opposition press. Firstly, the initial distance created to the full-back’s presser can delay the opponent from getting pressure on the ball. Then, the distance they have to make up to get pressure on the ball can result in spaces opening up diagonally infield.

As a result of common pressing schemes, the context of facing pressure in that position is consistent and thus provides the opportunity to prepare options to outplay the pressure. Due to spatial constraints restricting movement, it is key to prepare inside options on multiple lines in order to maximise passing lanes. Having more options can reduce the opposition’s cover of all options as well as restricting their ability to directly apply pressure. On a smaller group-tactical level, having a structure to allow you to adapt, and then adapting to how the full-back receives pressure is key too.

Once the ball is moved inside, clear follow-up actions are key to allow the attack to continue back inside into dangerous positions after the space has initially been opened up by stretching the opponent. The role of pinning actions by higher players is also key, to stop the opposition last line from stepping up to close the space opened up.

Moving a full-back deeper can be an effective structure for build-up but primarily against narrow presses and can be counter-productive against well organised wide pressing schemes. Therefore, it shows that the optimal setup is to indeed be flexible and adaptive to the opponent. While Liverpool are able to create dangerous situations from having Trent Alexander-Arnold deep, they can also have Jordan Henderson drop outside the shape while the right-back moves higher. Manchester City are effective with Oleksandr Zinchenko and Kyle Walker deeper but are comfortable in creating a back three structure in a number of ways. While using a deep full-back proactively can be an effective structure to build-up with, it’s ultimately about choosing the optimal structure to play against your opponent.

A key reason for writing on Spielverlagerung, and especially with theory articles, is that it allows you to challenge your own understanding of a concept. This can also be done in conversation too – thanks to author JD for his feedback in the process of writing this article.

3 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Sami Khan August 4, 2023 um 6:12 am

What is the difference between a deep fullback and a normal fullback? How does the deep fullback help with the weakness of the flanks and its 180 degree nature?

MSSP March 17, 2021 um 1:45 pm

Nice work, read this again to thoroughly digest this piece, very insightful concepts here and I already implement some with my team

Niv Uzan August 7, 2020 um 6:27 pm

Great work mates, I’m a also a coach and this is a pleasure for me to read the articles at spielverlagerung.

Actually I started to teach my new U14 team to play with deep FB’s becuase my Wingers are great players at 1V1 so I want to give them more space and now you are written about that.

Keep going!

TNX