Portugal reach the final in a tale of two defenses

Wales met Portugal in the first semi-final of Euro 2016, as Real Madrid teammates Gareth Bale and Cristiano Ronaldo went head to head for the first time at international level. With both teams landing on the more favourable side of the knockout draw, each had the opportunity to make an unexpected finals appearance.

Lineups

Due to odd disciplinary rules from UEFA, each team was hit with suspensions. A player is banned for the next game once he accumulates two yellow cards over the course of the tournament.

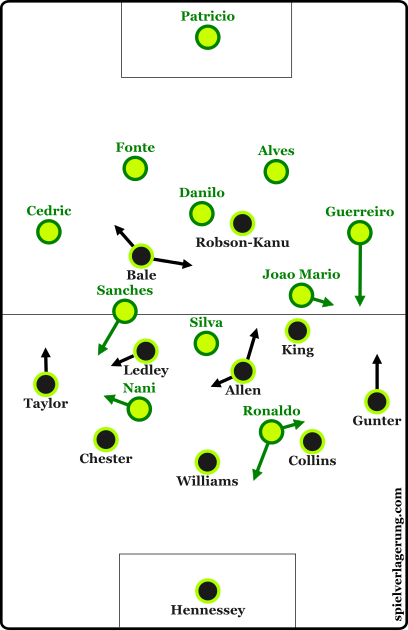

For Wales, this ensured key midfielder Aaron Ramsey, as well as defender Ben Davies, would play no part in the game. Chris Coleman elected to continue with the same system he had utilised throughout the tournament, with Andy King and James Collins coming in for the missing players. Collins would fill in on the right of a back three, shifting James Chester across to the left of the three.

Portugal were more easily able to deal with their lost player. Danilo comfortably moved into the base of the diamond to fill in for the missing William Carvalho. In a minor shift, Renato Sanches and Joao Mario switched sides from their match against Poland, with Sanches now operating on the right.

First half: A tale of two defenses

As has been the case for most of the tournament, both teams operated with a fairly passive medium block. The focus for both teams was to retain good structure until the ball entered their half. However, both teams utilised man-orientations to force long balls forward. This was generally successful due to the lack of suitable build-up structure for each team.

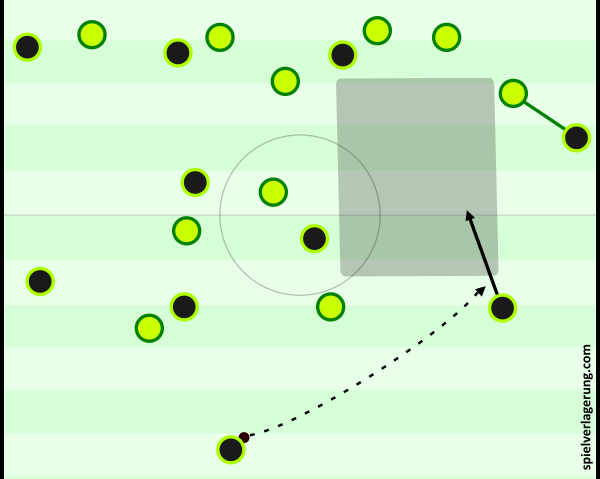

Wales were easily able to stunt Portugal’s ball progression with simple man-orientations in midfield. The ball-side wing-back would push forward to the Portuguese full-back, and the rest of the defense would pendulate to create a situational back four. The wide midfielder would then drift wide with the Portuguese midfielder when he inevitably attempted to fill this vacated space. With Danilo dropping between the central-defenders (covered by Robson-Kanu), and Adrien Silva dropping deeper (covered by Allen or Ledley), Portugal had no passing options. The far-side Welsh central midfielder could then act as a free-man, dropping deeper in midfield to sweep up any errant passes or pick up second balls from long passes forward.

As is almost always the case when man-marking, this regularly created space in the Welsh structure. The Portuguese players that were targeted for man-marking reacted well by rotating their positioning, dragging the Welsh markers away. But the second phase of the positional rotation was not completed – no-one filled the vacated space to receive the ball. This instead left a large space with little structure and few immediate passing options. Given the Welsh have used these man-orientations at various times throughout the tournament, it was likely they would do so again.

The far-side Portuguese central midfielder remained on the far-side regardless of how play progressed. When Danilo had dropped between the central defenders, this created a disconnect in the centre of the pitch and left no-one to move into the free space. This disconnect meant much of Portugal’s build-up came in the form of Cristiano Ronaldo knock-downs or hoping Wales did not suitably react to a quick horizontal shift in possession.

The major downside of the Welsh man-marking (despite the poor response from the Portuguese in early build-up) was the increased space this allowed for Portugal to regain possession of a second ball from these knock-downs. With only the far-side Welsh midfielder to cover a large space in midfield, Portugal were able to create an overload in these areas by dragging the Welsh midfielders away. With a team full of athletes, the Portuguese were often able to react quicker to reach these second balls anyway, regardless of an overload in the area around the ball.

Wales had similar issues in progressing play, but for slightly different reasons. Portugal focused on limiting space in the centre of the field by maintaining a narrow diamond shape against Wales’ build-up. Because of the passing angles created by the Welsh back three, this often forced play towards the wing-backs. At which point, the Portuguese midfield would shuttle across and limit the passing options for the Welsh wing-back.

This was particularly effective on the right-side, where Nani dropped suitably deep enough to create an open passing lane to the outside central defender, and narrow enough to continue forcing the ball wide to the wing-back. As Joao Mario was more inclined to move wide early in build-up, the passing option to Wales’ right wingback (Gunter) was generally not available. On the other side, Renato Sanches stayed central enough to allow the pass into the wingback, but wide enough and aggressive enough to immediately apply pressure and force a quick decision.

Because of this, all three of Wales’ top three passing combinations involved Wales’ left central defender, James Chester. He was often a prime cause of stagnant Welsh possession in early build-up phases. Insistent on using his preferred right foot, Chester closed many of his passing angles off by turning to face his wing-back immediately upon receiving the ball. This meant when Ledley or Allen had briefly found space in central areas, he was unable to quickly make the pass without adjusting his body positioning (or using his left foot!). This slowed the tempo of the build-up and meant his only passing options were to the wing-back or to Ashley Williams, both of which Portugal were happy to allow.

Possession was particularly stagnant on this side for Wales because it meant Joe Allen was temporarily man-marked by Adrien Silva in the centre. Throughout the early stages of the first-half, Allen’s reaction to this tight coverage was poor, and he generally stayed in the centre of the pitch without creating space or offering a passing option. The emphasis was then on Joe Ledley to receive the ball in good areas, but he often dropped into an already crowded backline instead. This improved as the game neared half-time, and Bale increasingly dropped into midfield to progress play.

There was also a [perhaps unsurprising] lack of inclination from any of the Welsh central defenders to dribble with the ball into midfield. After a horizontal shift in play, there was often space for the outside centre defender to push into midfield. But neither Collins nor Chester were inclined to do this. Whilst Collins is naturally not inclined to play in this way, he was also operating in an unusual (to him) back-three system. The space to move forward in this way is usually not available for him.

Joao Mario orients towards his wingback, leaving space for the mighty James Collins to burst into. Unfortunately this was almost never used.

Chester had similar issues with familiarity, but more due to the positional shift and the previously-mentioned difficulty in positioning his body upon receiving the ball. Particularly with Joao Mario moving wide to the wingback particularly early, this space was open for Wales’ right central defender to exploit, whereas Renato Sanches was suitably positioned to stop this movement.

Second half: Goals open the game

The game looked to continue in the same manner in the second half, until Wales’ man-marking defense of corners was ripped apart by Portugal.

Ronaldo make a fake movement toward the ball, before cutting back to gain himself a yard of space. Once this space is created, he is able to make use of his colossal athletic ability, and it is very difficult for any player to outjump him and win the header. He is also assisted by the basketball-esque ‘screen’ set by Jose Fonte in front of him, which denies James Collins access to the ball. Amongst British commentators and pundits, James Chester was the inevitable scapegoat for losing track of Ronaldo. Perhaps more blame should be put on the system that expects James Chester to match Cristiano Ronaldo’s movement and athleticism.

Portugal quickly scored another goal, after Collins & Williams remained too deep, allowing Nani to re-direct a Ronaldo shot.

This demanded a change in approach for Wales, and they made two changes to attempt to get back into the game. Sam Vokes came on for Joe Ledley, which created a slightly different midfield shape. Instead of Joe Allen operating between two other midfielders, he shifted to the left of a two – with Andy King dropping slightly deeper. Because of the off-centre positioning of the two double sixes, Adrien Silva no longer strictly man-marked either. Occasionally he would get ‘stuck’ on one, and Allen found himself in more space than he had previously.

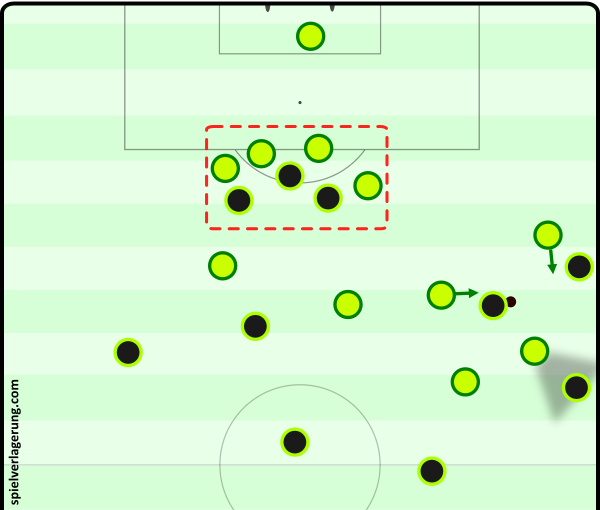

Gareth Bale played in more of a free-role, and often drifted towards the ball-side halfspace to receive a vertical pass directly from the wide central defender. This continued even after Wales made their change to a back four, with Williams coming on for Collins. As Gunter continued to push high on the right, Bale would drift infield and look to receive the ball in deeper areas.

But Bale’s proclivity to be situated anywhere but his right wing created problems for Wales. Using a similar defensive scheme as in the first half, with the central midfielder engaging the full-back in a wide area, Portugal were able to limit passing options whilst also pressing more aggressively. Having lack of presence in the ball-side halfspace when the ball is on the wing makes effective possession more difficult, but also makes defending transitions more difficult. Wales suffered with this throughout the latter stages of the game, and Portugal created a number of more dangerous chances in transition.

Poor Welsh halfspace occupation allows extreme compactness from the Portuguese backline, and an overload around the ball. Not only this – but it creates an easy transition once possession is inevitably lost.

Conclusion

The unavailability of Aaron Ramsey no doubt contributed towards a Welsh loss, but there were a number of other reasons they failed to move on to the final. Portugal played as expected – with a passive defense, intent on structure over pressure. But there seemed to be little change in the Welsh strategy to cater for this.

Portugal pushed play towards James Chester and the left-side, and he was unable to make use of it until Gareth Bale began dropping deeper. To create the passing angles to move centrally, it was vital the outside central defenders were positive in pushing the ball forwards, both in passing and dribbling. They were unable to do this, and so did little to test Portugal’s defense aside from basic ball shifting.

With a good halfspace and central structure, ball progression through the wing is possible. But the rest of the Welsh team was often totally isolated from the play, which made it difficult to push play back in-field. Whether it is the French or Germans that face Portugal in the final, they must ensure they are not simply pushed into wide areas and isolated.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen