Wales struggle past robust Northern Irish defensive display

Wales advanced to the quarter finals of Euro 2016 with a 1-0 victory over Northern Ireland on Saturday. Chris Coleman’s side, who attracted praise during the group stage with tactically impressive performances against Slovakia, England, and Russia. It was Northern Ireland, however, who impressed the most in Paris, as they prevented Wales from asserting themselves on the game with an impressive defensive display.

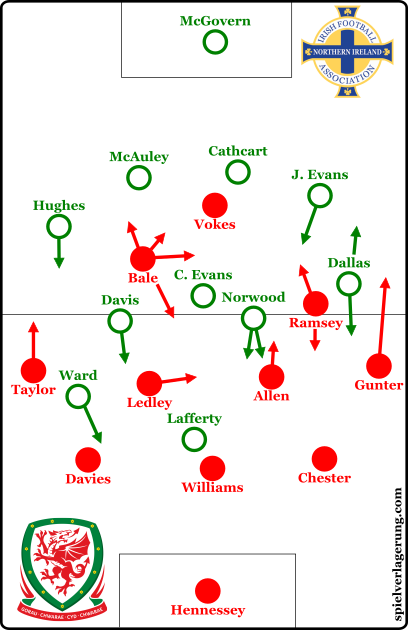

Northern Ireland’s man-oriented pressing

Michael O’Neill’s side laid out their stall very early with respect to how they were going to respond to Wales’ attempts to dominate possession. They employed a strongly man-oriented defensive system in the middle of the pitch when the Welsh centre-backs were on the ball. Steve Davis and Oliver Norwood looked to restrict any passes into Joe Allen or Joe Ledley, while Corry Evans would usually man-mark Aaron Ramsey in the centre of the pitch, occasionally pressing him when he took possession of the ball on the right hand side. On their left hand side, Stuart Dallas tracked with great interest the forward runs of Chris Gunter.

This had some interesting consequences. Since Gunter’s positioning was often so advanced, Dallas was regularly drawn into the defensive line. However, this was not mirrored on the other side, as Aaron Hughes would engage Neil Taylor’s forward exploits from left back instead of Jamie Ward. This led to a distinctly asymmetric 5-3-2 formation when without the ball.

Such a shift allowed O’Neill to play with his key players in their best positions. With the injury to Chris Brunt, Johnny Evans has had to fill the left back spot. By having Dallas drop into that position out of possession, Evans was able to slide inwards into his more accustomed centre-back berth.

Within this role, Evans was free to defend much more aggressively in the opening stages. With Gareth Bale looking at times to drift over to the Welsh right to combine with Ramsey – occasionally dropping deep to receive possession there himself – Evans would man-mark him, even staying tight to the Real Madrid man deep into the Welsh half if required.

Evans’ role extended beyond a simple man-marking job on Wales’ superstar, however. With Wales fielding four midfielders in the centre of the pitch, they naturally had a numerical advantage over the Northern Irish in that area. With the cover of two other centre-backs, Johnny Evans evened the numbers in midfield, acting as an auxiliary defensive midfielder at times, man-orienting against any player coming into that area, before dropping back into the defensive line once the immediate danger was no longer present. By combining these two roles, he gave Northern Ireland the security of a back 3 centrally, whilst also taking measures to restrict Wales’ ability to overrun them in midfield.

While Johnny Evans assisted in making the midfield a more evenly fought battle, it was the work of the more conventional midfield players which was most impressive. Indeed, his younger brother, Corry, played a pivotal role in preventing Wales from progressing through the middle of the pitch. His intensity in pressing – albeit from straightforward positions of access due to the strong man-orientations – were vital in preventing the likes of Joe Allen from being able to turn and play forwards in possession. Careful not to rush in too aggressively as to allow for an easy chance to dribble past him, he was able to reliably restrict Welsh possession centrally, to the extent where they struggled to build through there for most of the game. He worked diligently with his brother to ensure that he was not dragged too far away from the centre – passing players on with great intensity.

Jamie Ward’s curved run ensures that he blocks Joe Ledley with his cover shadow. Northern Ireland’s man-orientations further discourage Wales from playing infield – and indeed up the line. Davies ends up hitting a hopeful ball up to Vokes, who is unable to hold the ball up.

Further up the pitch, Ward’s role in Northern Ireland’s pressing was also interesting. As mentioned before, he did not mirror the role of Stuart Dallas on the left hand side, instead defending from a higher position next to Kyle Lafferty. From here, he looked to directly pressure Ben Davies when the ball was on his side, and moving across towards the middle when the ball was on their left. He did an admirable job of directing Wales to the flank through use of his cover shadow to block passes to the central midfield area, while also judging when there was sufficient coverage in that area to direct Wales into traffic. While directing a team infield is an inherently riskier strategy, with good enough access for pressing – which Northern Ireland could achieve through their strong man-orientations – it can also lead to turnovers of possession in areas much more conducive to counter attacks.

Kyle Lafferty, on the other hand, had a much more rudimentary interpretation of pressing. Namely that he barely looked to engage in any. Perhaps instructed to save his energy for when his team regained possession, he was considerably less intense with his movements against the ball. In addition, his use of his cover shadow to screen passes into Ledley or Allen was non-existent at times.

Wales’ fluid positioning in possession

The Welsh continued to show why they are considered one of the more tactically interesting teams at the Euros. Their fluidity in terms of positioning when they had the ball was such that it was often difficult to discern exactly what formation they were playing in. While the back three was stable, along with Taylor and Gunter on the wings, the midfield four of Ledley, Allen, Ramsey, and Bale rotated and staggered frequently. Given the expansive skill-set of each of these players, they are capable of fulfilling functions in any of the four central-midfield positions to a high standard.

In order to fit all of these central midfielders in his starting XI, Chris Coleman once again called upon a 3-4-2-1. Ledley and Allen started at the base of the midfield “box” while Ramsey and Bale played as dual tens ahead of them. The latter pair were given considerable licence to move freely throughout the formation, often both finding themselves in the right halfspace.

That is not to say, however, that Ledley and Allen were “stay at home” midfielders. Allen made several balancing movements to try and fill the spaces Ramsey and Bale left free, while Ledley occasionally took up positions in the right halfspace, in an attempt to create angles for diagonal passes into the centre.

The result was some interesting situational shapes. It was not uncommon to see Wales in situational 3-4-1-2, 3-3-3-1, 3-3-4 or even a 3-4-3 diamond in the opening 10 minutes. Given the sporadic nature of these shifts, and the differences in positioning of personnel within them, it could be argued that they were a result of the Welsh midfielders trying to receive without the pressure of Northern Ireland’s aggressive man-orientations.

Wales unable to break their man-orientations

As Neil Taylor receives the ball from Ben Davies, he is closed down from both the front and behind. With Aaron Ramsey and Gareth Bale given licence to move freely within the formation, there is no one in a position to take the ball off of Taylor.

Despite these efforts, Wales struggled to free themselves from the Northern Irish midfield marking. While Michael O’Neill’s men deserve a lot of praise for how they implemented this strategy, the fact remains that Wales put in arguably their weakest performance of the tournament.

The explanation behind Wales’ poor display in possession can be viewed through two scales: macro and micro, i.e. structural and individual.

On a structural level, Wales struggled to create connections to the centre of the pitch, often leaving the flanks isolated. With Northern Ireland effectively deflecting many passages of play towards the flanks, Wales were often unable to recover from this, and thus turned over possession. They were not helped by their opponents’ ability to create overloads on the flank when they loosened their man-orientations slightly. In this respect, the roaming movement of Ramsey and Bale were at times detrimental to the team’s possession play, taking them away from areas where they could support the ball adequately. Similarly, the decision to play into these areas in the first place must be questioned, especially in situations where there were never any connections to other areas of the pitch should the receiver be placed under pressure.

Looking deeper at the individual level, the situation improves very little. Again it must be emphasised that although such strong man-marking is far less common in the modern game than it once was, thus making it a more unfamiliar approach to deal with, that should by no means have rendered Wales as sterile as they were in the first half.

In his excellent theory piece on creating a game model, RM examined the key factors in overcoming man orientations.

Yet, if the opponent man marks, you don’t have such lines [to play between]. The opponent will follow you, this creates messy shapes and you’ll have problems to position yourself behind the opponent due to him marking and running after you, normally staying at your back. Here are other things important which are called ‘dismarking’ by some experts like the people from 3four3 from the US. On a surface level there are some fundamental (and interconnected) ways to leave your marker which I just want to mention and will explore in a tactical theory article someday:

Distraction & miscommunication

Misdirection & Deception

Dynamical Positioning

Positional Rotation

Specific passing patterns

Dribbling & Receiving

While it would be possible to examine Wales’ possession difficulties through each of these lenses, it is possible to summarise it through one. In order to escape a man-orientation, it is important to be dynamic. Since, by definition, a man marker is reactive, they often have to anticipate in order to prevent them from being left behind. It is possible to take advantage of this through dismarking – in particular through positional rotation, dynamics and deception. In Wales’ case, they were far too easily marked due to a distinct lack of movement. This made it increasingly difficult for players like Allen to receive the ball facing forwards, leaving long, hopeful, diagonal passes the only route forward.

Conclusion

Despite these glaring problems, Coleman’s side came away with a victory. McAuley’s own goal in a dull second half was harsh on Northern Ireland. Despite their style of play no doubt being somewhat unpopular amongst SV readers – and indeed writers – there is no doubt that it worked. Dictating the game without the ball, reducing Wales to poor excuses of attacks, Michael O’Neill’s side may not have been the neutral’s favourite, but they executed their game-plan well – which is more than can be said for their opposition.

It is Wales, though, who march on to the quarter finals, facing the winner of Hungary v Belgium. Before they are to start dreaming of a potential semi-final spot – especially considering that their half of the draw is slightly weaker than the other – they will need to greatly improve their possession play.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen