Bayern Munich – Borussia Dortmund 0:3

Bayern go down against the Dortmund Pressing machine. Jürgen Klopp came up against Guardiola’s brand new tactic experiment with something special. How did he know? Probably because Klopp like Floyd Mayweather exists in the future. Or because it was the same situation as the game against United – with similar problems, but against a better opponent.

Guardiola and the Curse of the Pharaohs

Normally one speaks of the football tactics proceeding chronologically, but repeatedly uses previous aspects and thus a kind of circuit is created. At the beginning of this process was, among other things, the “pyramid”; the so-called 1-2-3-4/1-2-7, which developed from the first few years (1-1-8 or even 0-2-8). Even the later 2-3-5, which was prevalent for years, looked like a pyramid and is usually equated with this. In modern football this pyramid was, as Jonathan Wilson so beautifully expressed in his book “Inverting the Pyramid”, or vice versa. Guardiola already tried this development at FC Barcelona ( sh. these beautiful article ).

What does all of that have to do with the game on Saturday? The formation on the offense looked like a different historical formation – or even as a combination of two famous formations. The “Metodo” (Italy’s successful system in the 1934 and 1938 World Cups) was a 2-3-2-3 or a 2-2-1-2-3 run by Hernan Crespo, in which the “full-back” defensive six was the central player for linking play between midfield and attack. The WM system was a 3-2-2-3, which was promoted by Herbert Chapman at Arsenal FC and for over twenty years represented the formation in the world of soccer.

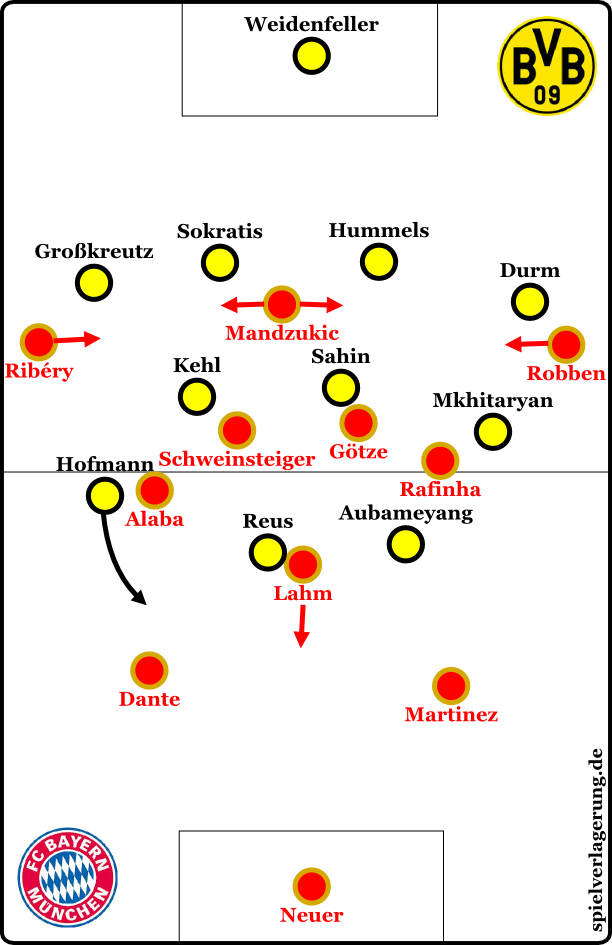

From their actual 4-2-3-1-formation Bayern shift in again and again to these two formations while in possession. But on his way back into the past, Guardiola may have incurred the Curse of the Pharaohs by inverting the pyramid: It just does not work. The advantages are diminished in this extreme and constant execution of the tilting of the full-back. This has two major causes.

A constant and extreme indentation of the full-back takes away from both the flexibility and the dynamics. Because the player is no longer shifting situationally but is stereotypically in the middle, they actually provide less rather than more space. The overload of space and opponents in the centre, the dynamic opening of the passing lanes to the winger and the space creation of the full-back itself becomes only one thing: A static formation.

Because they were no longer switching between wide positions and tilting when the situation demanded, but on almost every attack, the opponent was able to easily adapt. The actually very positive tilting of the full-back – leaving the position and filling the center to create new passing options in midfield – thus loses its effect. This was, however, also because Dortmund had an excellent game plan.

BVB parks the bus – but on another car park

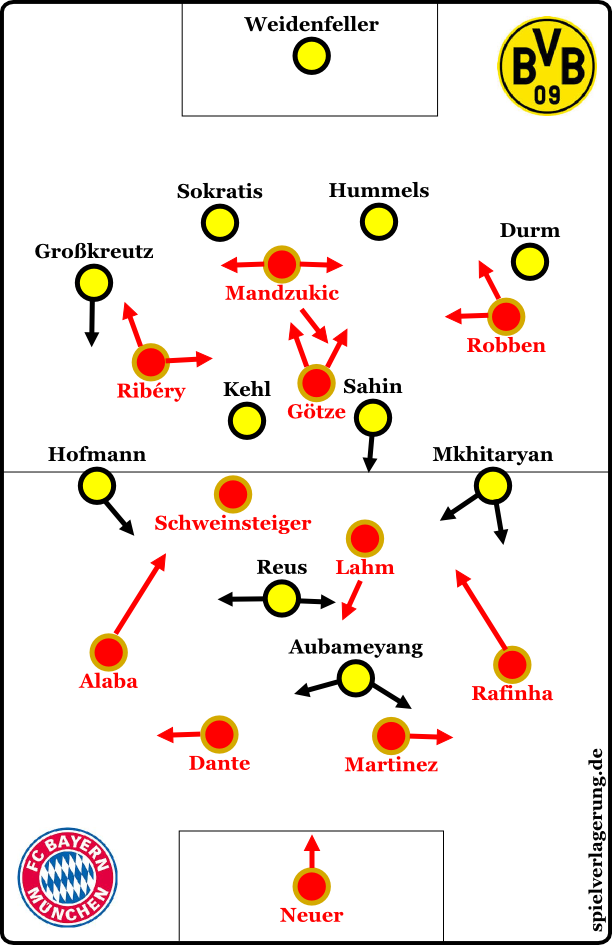

Unlike his counterpart, Jürgen Klopp remained mostly faithful to Modern tactics – but without innovation to really drop. The Black and Yellows played nominally in a 4-2-3-1/4-4-1-1 press, but the group tactical movement, the situational orientation, and the adaptation to the opponent’s body movements were all worthy of honor. Dortmund skillfully changed again to a 4-4-2/4-2-4 or an asymmetric 4-3-3, the latter proved extremely effective.

Reus oriented in the center as the ten against Philipp Lahm, but moved forward frequently; pressing on the center-back when it was possible. His drive predestined him for that, while at the same time trying to keep Lahm in his cover shadow. Aubameyang played as the nominal center forward, but shifted a little to the left. From there he could run at Martinez and had a simpler defensive role than he would have in the middle.

The previous ten, Henrikh Mkhitaryan, moved (as in the game against Real Madrid) to the left wing, playing somewhat deeper than his opponent. The 4-3-3 and the asymmetry arose from Mkhitaryan’s positioning. Jonas Hofmann on the right wing moved forwards repeatedly, sometimes pressing with a diagonal run at Dante, clearly playing much higher than Mkhitaryan on the other side. With the positioning of Aubameyang and Reus the offense was briefly in a 4-3-3. Hofmann also moved to man-mark the indented Alaba while Mkhitaryan handled Rafinha but in a different way.

The 4-3-3 arose most often when Alaba indented. This could for example be because Aubameyang just left Mkhitaryan to rather focus on the space between Rafinha and Robben in a lower position, while Hofmann indented with Alaba and continually pushed forwards to press Dante. Alternatively, one could see Alaba as a greater threat than Rafinha, which is why you would rather Hofmann as the dominant element.

This 4-2-3-1/4-4-2/4-3-3 was played very cleanly. Reus, the winger, and the six behaved very situationally, with great intelligence, and made very few mistakes in carrying out their assignments. Hofmann pushed forward, for example, by tracking Alaba with arcing runs to the side and covered the direct pass to Ribéry several times.

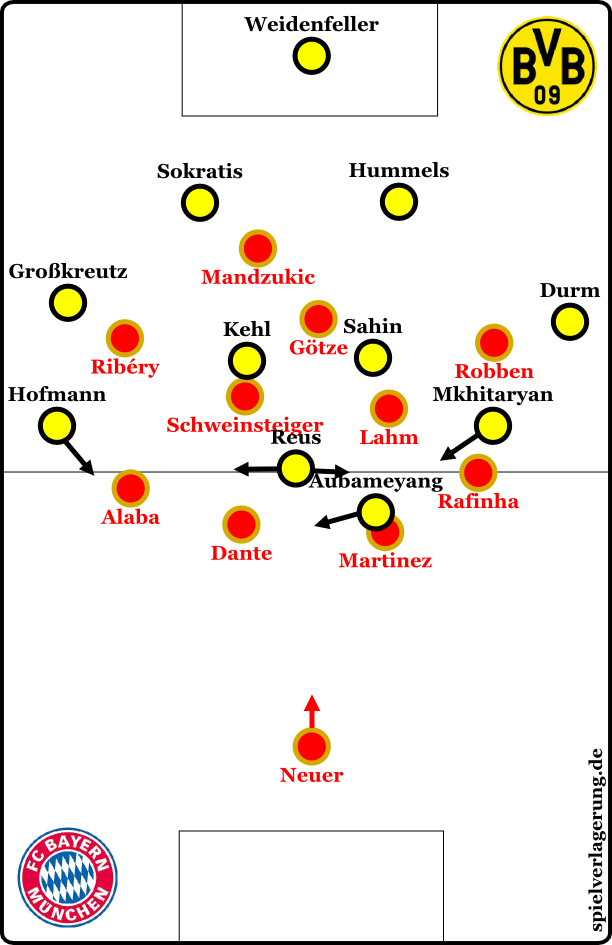

Dortmund was able to press in the front line or in pairs, without as much intensity as one would have expected, but showed everything defensively in an absolutely world-class performance. Their wingers always had access to multiple passes and could find each other in the cover shadow when pressed. The sixes were also excellent, the center-back also pushed well forward and partially protected the very wide track of the full-back from Robben and Ribéry. There was hardly any space in between the lines for Bayern.

Instead of their usual ball circulation in the opponent’s half, Munich were isolated in their own half. They only came forward on the wings, but because of their 3-2-2-3/2-3-2-3 formation the very wide wingers rarely had the opportunity to be effective because the attack channels were unsuitable and most of their attacks were eaten up by the very intense ball-oriented movement of the Dortmund.. This was also the biggest difference in the attacks.

Both sides had similar attacking patterns, but …

BVB had the better spatial and playing conditions. Reus played in some aspects like a “new Lewandowski”. He was the target player for Ablagen, he dragged the ball with him in Umschaltspiel (transitions) and because of his control he provided movement and space; he broke, of course, differently than Lewandowski and also moved into other areas, but was similar in principle. This of course was a foil to the direct vertical play behind the high Bayern defense, where Aubameyang would win every foot race against Martinez. From his half-left position he could help on the wing or go centrally to the tip of the formation. Bayern’s offside trap here was very risky, but worked very well several times catching BVB offside 9 times.

There were also triangular movements between Aubameyang, Reus, and Mkhitaryan. The latter moved from the wing and was able to target open spaces with his vigor and intelligence, Aubameyang took off deep, and Reus commuted between his central position and the left wing. On the other side Hofmann moved often and Kevin Grosskreutz supported him with runs from deep. When Hofmann and Grosskreutz came forward to attacks from the right, Aubameyang, Reus, and Sahin supported them near the ball.

Bayern had similar movements, but under very different conditions. They were not playing against a team that patiently builds up, who open the wings (only 22% of the Dortmund attacks went over the middle) and leave a lot of space behind the defense. Nevertheless, Bayern’s passes often went to the wings where Robben and Ribery would then go their dribbling skills. Götze and Mandzukic ran diagonally in deep, trying on the one hand to open space for the dribbling wingers and on the other hand to free themselves. Alaba also occasionally ran in deep and tried to break through in the middle, but was ineffective.

This simple idea only worked once, when Götze missed a large opportunity due to a run and a pass by Robben that was already (wrongly) blown offside by the referee. Although the full-back/six ensured a relatively stable circulation in the first third, Bayern had little chance going forward. They were isolated in their attack, had little circulation in the middle, and a few clean finishes.

Again and again they had to rely on the flanks, shots from distance, and a few overload attempts to break through, but BVB had an excellent handle on the game. The later following changes by Bayern didn’t change anything.

The adjustments in the game

Josep Guardiola, as usual, fixed some movements in the buildup. At first Lahm was tilting almost constantly, then Schweinsteiger took over this role in order to have Lahm move forward into the narrow zones, later there was no more tipping. The full-back only tilted in situationally or generally remained wide and the offensive movement was played a little differently. But there was no real difference. Everything was sucked into the compact pressing vortex of BVB; whether it was modified positioning in midfield or flexibly overloading the winger in central zones.

After an hour, Thomas Mueller came on for Ribery and provided more movement centrally. With the third change (at half-time football god Manuel Neuer was taken off for Lukas Raeder) Toni Kroos came on for Arjen Robben in the 69th minute. Now Müller moved right, Goetze came up the left side and the system was again 4-1-4-1 ish. Effective? Not really.

But Guardiola wasn’t the only one to make changes. Jürgen Klopp also brought Robert Lewandowski on after an hour when the score was 0:3 for the scorer Jonas Hofmann – an almost ironic change. Lewandowski had difficulty with his central position and Aubameyang joined on the wing and also had some problems with his defensive movement. Bayern were unable to capitalize, but there was certainly a decline in BVB’s performance. A few minutes later brought Klopp on Manuel Friedrich; a change which almost recalled the Benaglio exchange of Felix Magath 2008/09 against Bayern. Jojic came on for Aubameyang and now occupied the right wing and BVB played the game down even more confidently.

Conclusion

That BVB had only four crosses and Bayern came to a full 18 meant the win for BVB was well earned. They optimized their access options within their own formation at the highest level almost continuously (to borrow from my colleague Martin Rafelt), which allowed them to neutralize the movements of Bayern. Their game plan, with the indenting Mkhitaryan who was superb on offense and defense again, the elusive and/or ball carrying Reus, the couple on the right, and Aubameyang’s athletic forward runs, was very effective in counter-attacking.

The Bavarians, however, could did not utilize Götze’s combination game properly. The wingers had little access to the box, Mandzukic was removed from the game and otherwise there was little offensive presence from the players behind them. It is a shame that this game did not take place in the first half of the season when there was something to still play for. This time the game gave us the tactics and strategy that the first game promised.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Addis April 18, 2014 um 1:08 pm

Excellent article Rene. Please keep up the English version your site at least for great game. I expect Champions League semi finals analysis also.