In-depth analysis: Bayern Munich – Barcelona 4:0

Bayern defeated Barcelona 4-0. This game will probably go down in history for two reasons, as we might have witnessed the fall of one great team and the rise of another. Rarely has such a highly anticipated meeting of more or less equals been so clearly decided. It’s almost paradox in nature, for most people would have attributed Barcelona with an individual superiority.

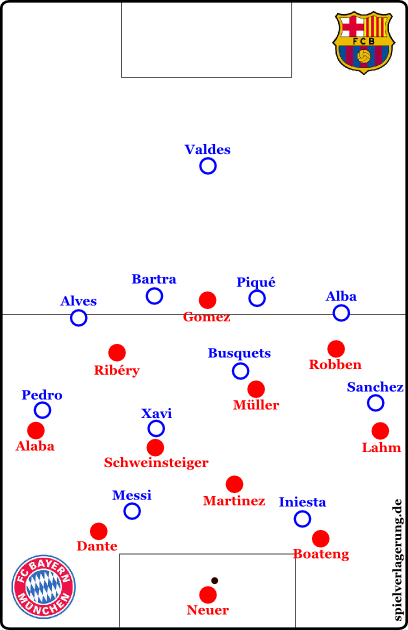

The tactical preparations of both teams may of course be decisive in such a game. Bayern played without Mandzukic and Kroos, while Puyol and Adriano were missing for Barcelona. Thus, several changes were forced on the teams. They were dealt with in different ways, with different tactical backgrounds.

Alexis Sanchez and Pedro

Unlike in the game against AC Milan, Barcelona featured Sanchez (on the left) and Pedro (on the right) as wingers instead of Villa and Pedro. In this setup Alexis was probably supposed to provide width. Due to his dribbling skills, he’s better moving into the centre from the side when Alba remains in a deep position. When Alba pushed out, Alexis remained as pressing resistant open man in left half space. There, he was supposed to support Andrés Iniesta, who had to move deeper as expected due to Munich’s pressing.

Pedro was placed on the right to support Alves’ forward movement in defensive transition play (reaction to the moment of a game on the break). After ball losses Pedro repeatedly sprinted back to cover for Alves.

They probably had identified Munich’s left side with David Alaba and Franck Ribery as the more dynamic in transition play (“Umschaltspiel” in German), of course especially because of Alaba playing as fullback. Pedro was a logical choice on the right and quite a good idea of Tito Vilanovas to deal with Munich’s style of play.

Bartra as half-right central defender

The second question concerned central defense. Would Vilanova choose Eric Abidal or young homegrown Bartra? Bartra’s appearaence in the line-up seemed likely, seeing that Abidal had just returned from a long injury break after a grave illness – and Bartra ultimately played.

The Spaniard was used as a half-right central defender, while Piqué went to the left. Again, it was probably an adaptation to the opponent’s left side.

Munich’s left wing featured Ribéry and Alaba, two extremely dynamic players strong in transition play. There was also a larger formative hole in the offensive line-up there, as Alves moved up higher and earlier. Barca wanted to place their faster player there, and against Ribéry,

Bartra moved out tremendously well a few times. Piqué remained in the centre. Due to his superior passing skills he was the better safety option.

Mario Gomez and Jerome Boateng

At Bayern, however, there were also two questions: Who would play in central defense alongside Dante, and who would feature as centre forward?

In defense, Heynckes opted for Jerome Boateng as Dante’s partner in central defense. The idea was simple: Boateng is faster and thus more variable in the height of the pressing employed, without being unstable against Barcelona’s fast wingers pushing into space.

Van Buyten was preferred in many games, as he is generally more stable. You could probably put it like this: Van Buyten is better able to control a given specific space, while Boateng is able to dominate more space.

This capability can be extremely important against Barcelona, in a potentially chaotic game due to many situational man-markings. In such a situation you need athletics and dynamic bridging of open space. Choosing Boateng was therefore the right adaptation to the game and its events.

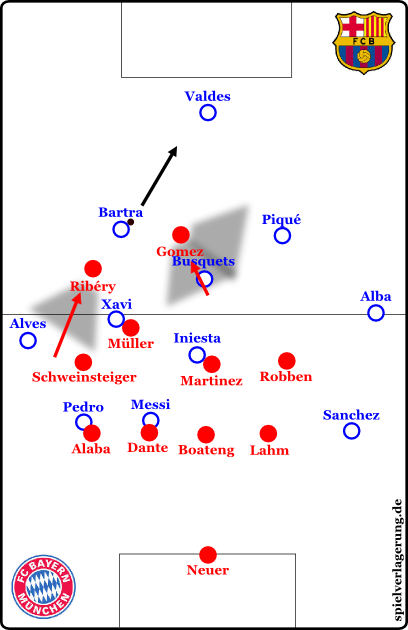

In Gomez’ case, it’s more difficult. He wasn’t employed like Drogba was against the Catalans, with many long balls directed at him up in front. His muscularity was not used directly as well. Situationally it came into play, as did clearences directed towards him, but not as a primary tactical style. Instead, it was probably Gomez’ backwards pressing which was decisive in choosing the German international striker instead of competitor Claudio Pizarro.

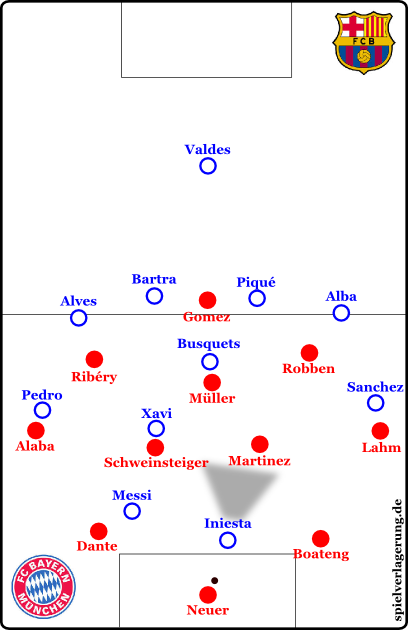

Again and again we saw Gomez orientated backwards, with much physical exertion. His pressing priorities were Busquets or the two Eights. At several times he looked for individual victims in half-space (like Messi). He sometimes found himself even on a level with the midfielders, as well as Thomas Müller did. Thus, the Bavarian playing style also differed fundamentally from the defensive orientation of the Catalans, as described in the next paragraph.

Barcelona pressing

In world football, Barcelona’s pressing was one of the most variable in recent years. A position-oriented 4-1-4-1 with midfield pressing was as possible as a 4-2-4 or 4-3-3 in attack pressing. In this game, they resorted to a specific version of their 4-1-4-1. In pressing like this, one of the Eights situtationally orientates himself forwards and supports centre forward Lionel Messi in pressing. They often play even higher than Messi and even replace him entirely in pressing.

Against Bayern Munich, for example, there was a scene where Messi trotted to the right wing and stayed there. The intelligent strong runner Pedro moved to the centre, while both Iniesta and Xavi pushed forward and constructed an asymmetric 4-3-3. Otherwise it was mostly a 4-1-3-2 (as a variant of a 4-4-2) instead of a 4-3-3,

This was created from the 4-1-4-1. In many games Barcelona presses in a 4-3-3. Here, the wingers of the 4-1-4-1 are positioned higher and help Messi press. In the 4-1-3-2 variant, the wingers remain deeper, and the Eights situationally push out to press the central defenders with Messi.

Normally, this works exceptionally well because the Eight puts one of the opponent’s build-up players in covering shadow. He then runs dynamically at the central defender in charge of the ball. At the same time Messi blocks the passing route to the other one. Often, this leads to a pass back to the goalkeeper, and both his passing options are covered.

Barcelona pushes further forward and presses the goalkeeper. The oncoming attacker puts the previously covered centreback in covering shadow and prevents a pass. The Catalans wanted to employ this way of playing against Bayern. In addition, wingers positioned deeper were supposed to largely isolate Munich’s dangerous forward movement on the wings (employing movement to create supercharging, and a tilting Six). But there were several problems, making Barcelona’s pressing ineffective.

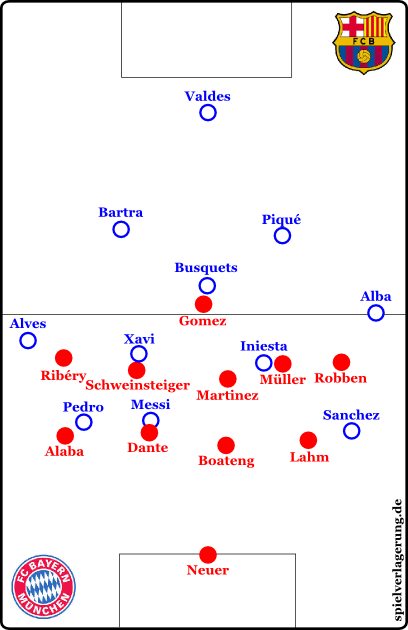

Bayern avoides Barcelona’s pressing

An important factor was Manuel Neuer, who is difficult to press. He is able to play precise passes through narrow spaces, or to deliver clearances directly. If Barcelona pressed him, then he played good passes to the retreating fullbacks, into open space in midfield, or long balls far forward. There, Bayern won the bulk of aerial duels, and in their physical superiority they were clearly stronger in collecting the resulting second balls. Thus, they conquered space easily and quickly.

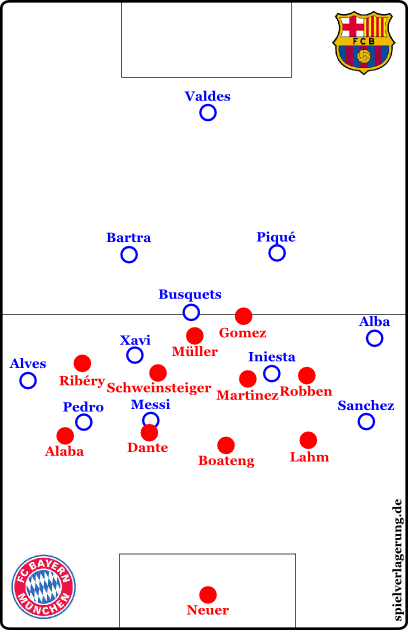

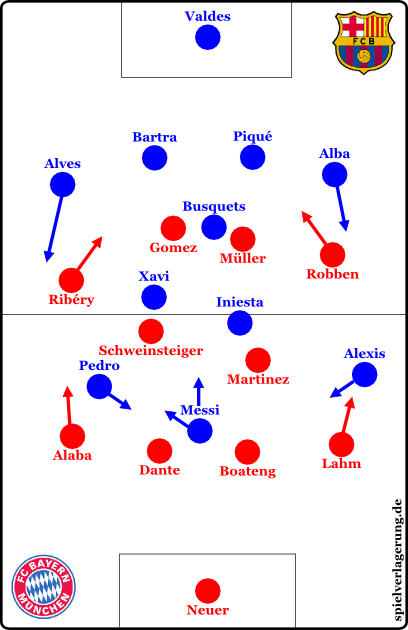

If Neuer was not attacked, he remained calm and waited until his central defenders had spread. Together they often formed a bank, circumventing Barcelona’s pressing. Due to the very wide positioning of the centrebacks Barcelona’s two strikers were pulled apart, and sooner or later a Bavarian player could free himself: either one of the central defenders, or in defensive midfield where Bayern had superior numbers against Barca’s lone Eight, made possible (especially in the first half) by the freewheeling Ribéry falling back, the agile Double Six, and Thomas Müller.

Bayern circumvented the problem of a pressed central defender in a classic manner: A Six drops back, gets the ball from Neuer and bounces it on to the centreback – the pressing striker’s covering shadow is bypassed. The central defenders’ deep and wide positioning stretched Barcelona’s pressing formation and expanded these spaces even further. The centerline became practically the boundary for offsides and did the rest.

While Bayern had mostly vertical distances of five to 15 meters per line and a maximum of 25 meters of distance between defense and attack in their pressing, Barcelona had to be content with a total of 40 meters. The defensive line remained at the centerline, Busquets providing security in front of it. The wingers often orientated themselves in man-marking towards the Bavarian fullbacks pushing out. But the strikers had to press far forward, into Munich’s box, which of course opened up large space in midfield.

Manuel Neuer and the defensive players used this space, Thomas Müller moved exceptionally. Physical superiority, dynamics in transition play, and good positioning in build-up play resulted in won second balls. In the first half, Ribery also fell back several times and acted fluidely in his positioning. He also moved into central midfield or to the right in order to pick up the ball.

Thus, Heynckes probably wanted to bring more creativity into the game, more stability into build-up play, and to increase numerical inferiority in Barcelona’s pressing formation. It was a success. Ribéry was also able to dodge covering shadows. He is technically strong enough to profit even from difficult passes.

Interestingly, Barcelona had their best short pressing phases when Alves reacted strongly to Ribéry’s falling back. The Brazilian then moved to the front and pushed out because he had no opponent. He increased pressure. But these individual scenes fade in hindsight, and Ribéry’s decreasing backward movement made sure that probably no one remembers these situations because they could not decide the game.

Another factor in overcoming Barcelona’s pressing concerned the forward movement on the wings.

Bayern on the wings

The formative stretching of the Catalan pressing formation by the bank of three formed by the goalkeeper and the central defenders was the determining factor in nullifying the by no means weak pressing of Barcelona. The second major factor was the Bayern’s forward movement on the wings, where they used the large holes in the opponent’s pressing. This was particularly noticeable in Thomas Müller’s actions.

When Bayern had the ball, the nominal Ten shuttled repeatedly from right to left and connected with the players on the wings. This allowed the newly crowned German champion to take advantage of the space between the opponent’s fullback and winger, as Müller (and Gomez) played fast rebounds to the side.

If Iniesta presses the goalkeeper, Neuer can also play back to Boateng, who is freed when a bank of three is formed.

In addition, Bayern have of course the ideal team for such a style of playing. Schweinsteiger and Martinez can offer themselves in half-spaces and secure them at the same time. Both also went forward, did not secure the centre but supported the offensive play in half-spaces and through vertical sprints, which had several effects.

On one hand, they could make the game more deep and offer themselves. Their sprints from depth destroyed all attempts by Barcelona to use position-oriented zonal marking. Even in the early stages Martinez’ breakthrough created a great opportunity for Robben, but the Dutchman failed to score. Their forward movement provided depth and extended the space between the lines. If they did not push out, Thomas Müller took over with many vertical and diagonal runs after rebounds.

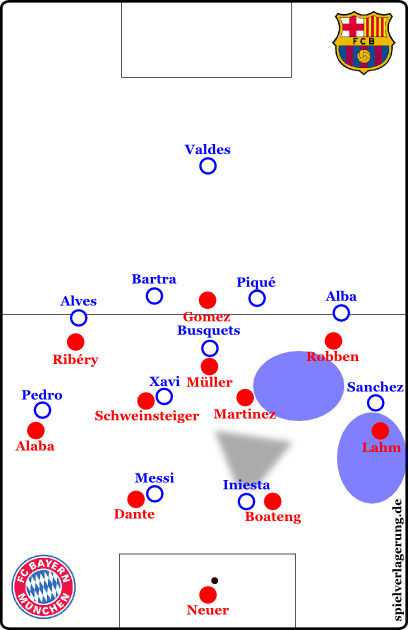

In addition, Bayern has extremely intelligent, pressing-resistant and technically strong wingers: Ribéry, Robben and the fullbacks. Both Alaba and Lahm can also play diagonally, making Bayern more flexible in the occupation of the wings. Both the fullback and the winger can provide more width to the game in the final third of the pitch. Especially in the final phase you could see at several times that Lahm diagonally attacked open half-spaces in the opponent’s formation while Robben remained wide.

Bayern was thus able to play some crosses and, with fast combinations, could overcome a lot of space in a short time. They did not aim for high crosses, but rather for precise passes into the box or, situationally, corners. Again and again, FC Barcelona’s aerial inferiority in standard situations has been identified as their biggest flaw. In recent years, all experts have emphasized that Barcelona can be hurt with good old crosses, long balls, free kicks and corners.

This is the gist of the matter, but only indirectly. Getting long balls to a centre forward is a difficult matter. There is only one Drogba in the world – and against Piqué and Puyol, many good tacklers lose in quite a number of their attacks. But even in case of successful ball handling there is no further support if your team has been pushed back too far as a collective. And many clearances do not come through, due to counter-pressing, but often end up with the nice man with the bobble hat in row 14 of 7B.

There is a similar problem with standards. Normally, most teams may rejoice in case of a corner gained against Barcelona, as they are very rare. In counterattacking most teams also aim towards the goal and want to use space, where they often fail in defensive duels. This results in a throw-in and a ball loss in pressing. Corners are hard to get, and free kicks from a good position as well – also because of the really high pressing.

Bayern could get these corners because of their fast movement through space and combinations on the wings. Instead of playing crosses (while still running) to Gomez, Müller, and probably one of the Sixes (weakly secured and outnumbered), they created clearer situations through corners.

Behavior in standard situations may be analyzed; Barcelona, for example, plays with a clearly analyzable zonal defense at corners. The defensive strategy in these standards may also be organized almost perfectly. A static ball may be aimed with more precision, and there is also the possibility for complex tactical group movements in the centre, with a larger specific individual quality, in this case concerning headers. Heynckes’ men could use Dante’s aerial capabilities, which would have been impossible otherwise – he would have perished in defending against counterattacks.

It is more than appropriate to praise Heynckes and his team – it’s easy to demand dangerous set pieces against a team that’s weak in the air. Its implementation is another matter, especially against a pressing team with lots of ball possession. Bayern solved this task excellently, and in combination with the overloads on the wings it was the second major factor in this historic victory.

A final factor concerns the individual tactical approach concerning clearances.

Bayern resurrects dead space

The Catalan pressing was, at least under Pep Guardiola, that strong because they could “kill” open space in impressive fashion. They used their covering shadow and the psychological and tactical factor of high pressure in order to make space unplayable. The covering shadows complemented each other, blended into one another, and certain zones were isolated from others. Simply put: The opponent was chased from one closed down area into another until he lost the ball.

This “killing” of space has been lost a bit since Guardiola’s departure. Nevertheless it exists, and Bayern could neutralize this killing of space surprisingly well, especially in individual counter pressing attempts from Barcelona players. To this end Bayern employed a risky play combining short and long passes.

Instead of working with blind high balls, they tried at several times to play long, flat and very sharply played balls through the middle. A flat ball is easier to handle. Because of its sharpness it can hardly be effectively absorbed in counter-pressing. If it is received by a teammate, a counterattack starts immediately. If it is intercepted, the collective could at least not yet react with a premature forward movement. Besides the opponent is disorganized due the attempted counter-pressing and has to rearrange in his offensive formation.

If Dante moves out, Barcelona can play passes into space for Alves, Sanchez or Pedro. Boateng is supposed to prevent that, f.e. by employing his dynamic abilities

Of course there were a few clearances besides these passes and balls along the line, but these did not seem “rather random” but to have been more deliberately played balls. The classical clearances (responding to pressure) were increasingly replaced by very sharp flat semi-high balls. A few times those balls passed the opponents so closely that to play them almost seemed insane.

Thus Bayern had more stability in their style of play, and there were no really dangerous counter-pressing scenes from Barcelona. Bayern almost perfectly neutralized Barcelona in all respects, even in their offensive.

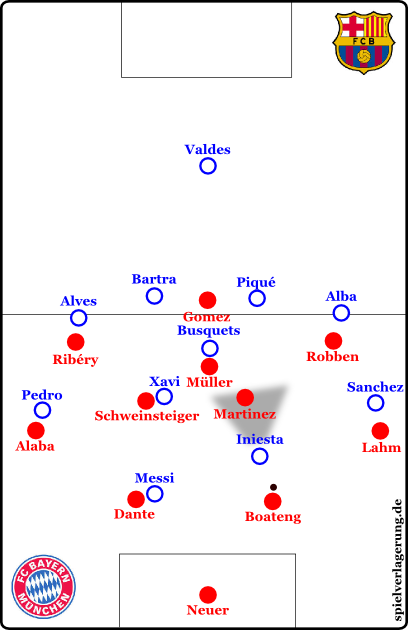

Bayern’s pressing – A kingdom for Xavi, a cage for Messi

Jupp Heynckes chose to press in a 4-4-2-0, and it was the right decision. With Gomez and Müller close to midfield, Xavi and Busquets were taken care of as well. Xavi often drops deep next to Busquets while Iniesta provides connection to Messi in front. The 4-4-2-0 pressing let the opposing central defenders be, and the compactness of this formation made many situational man-markings possible.

Some were employed very frequently. In the first half, Schweinsteiger was orientated himself often towards Xavi while Thomas Mueller and Mario Gomez took turns in checking Busquets. Javi Martinez took care of Iniesta, who had to drop deep a lot due to Munich’s compact formation and the control exerted on Busquets and Xavi.

The advantage of these situational forms of man-marking in a maximally compact formation (formed as high as possible and based on a positionally orientated 4-4-2-0) is obvious. Its tightness facilitates man-markings where physical advantages may be employed. This forces Barcelona’s players to look for free space, but these exist only in the defensive areas of their own formation.

Therefore, Xavi and Busquets dropped again and again into safe space. They were then positioned in front of Gomez and Müller who only occasionally pursued them further back. They abandoned the Catalans to the playing vacuum of the defensive structure space and then went mostly back to their position if possible. Then they had a horizontally and vertically enormously compact 4-4-2-0-position into which dangerous passes were hardly possible.

Xavi had so much room. He could actually do whatever he wanted to in his own half of the pitch. But it had no effect. Does the reader know Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”? The following is written in the second scene of the second act:

“O God, I could be bounded in a nutshell and count myself a king of infinite space, were it not that I have bad dreams.”

This is exactly what happened to Xavi when he played against Bayern. He could have gone to the corner flag or tilted back between the central defendera – he had all the space, time and ball contacts he might have needed. Barcelona had, after all, ball possession beyond 60%.

Bayern’s pressing formation with Schweinsteiger pushed out. Thanks to the deep strikers, Messi can’t be reached, except with high balls. But if there is something Messi cannot win, it’s an aerial duel with Dante.

But Xavi was bound in a nutshell. His real area of impact was small. His “bad dreams” were the compactness and physical superiority of Munich, for all passes to Barcelona players within this Bayern block looked like passes to man-marked players because of the tightness of space – and thus they were almost direct passes to the opponents.

In contrast to Andrés Iniesta, Xavi cannot outplay a Bavarian bull in a nutshell, and consequently he was totally taken out of the game. The king could not rule. If he did not drop deep, the central defenders had to take over build-up play but had no open players in reach. This resulted in balls long and lost.

Even the king’s best servant could not save the day. Lionel Messi played from the beginning, but all of his actions lacked effectiveness. Bayern had crafted a cage for the four-time world footballer. Position coverage and situational man-markings kept him apart from his team. The compactness and the midfielders’ backward pressing provided immediate distress in space between the lines.

Dante completed the rest. At several times, the Brazilian moved very far out along with Messi, if there was no possibility to hand him over in closed-down space. Mostly, Dante moved with Messi until the latter was caught in a dead zone. In this dead zone, he could either not be played at, or he couldn’t process received balls any further.

In a scene where Bayern’s order had come into some disarray Dante followed Messi for almost 20 meters. It rarely lasted that long until Messi was in a dead zone again, thanks to the excellent team effort. Positioning cover and the situational variability of Alaba and Lahm as markers of both zones and men ensured that Pedro (moving inside for Messi) could also be taken out of the game if needed – but the FC Barcelona seldomly took it that far.

Position-orientated zonal marking and situational man-marking interacted positively. Thanks to positioning cover the team could quickly organize and stand compactly, the situational man-markings were possible because of the tightness and thus a stable performance; thanks to situational man-marking passes into the formation were less dangerous, which in turn made the positioning cover more effective.

This meant that only 24% of Barcelona’s attacks came through the middle, as it was constantly shut down. Normally, this value is far above that of the attacks carried out on the wings. It also forced Barcelona to play many diagonal balls that were supposed to overturn Bayern’s compact block and strong horizontal indentation.

However, this failed. Alaba and Ribéry just like Robben and Lahm showed that they were capable of excellent shifts. And there was another factor.

Water on the pitch

In the centre of the field there was a lot of water, even though the day was quite warm – according to the commentator. He claimed that the pitch had been watered intentionally before the game, with the aim of restricting Barcelona’s ball possession game. There are other possible explanations for this, but it had an effect on the game – and effects, as it is well known, do not really care whether they were intentionally caused or not.

The focus on different attacking directions was certainly an advantage for Bayern. Bayern relies much on the wings and half-spaces, while Barcelona dominates the middle. They use half-space only in the last third of the pitch. Therefore, a puddle in the middle would do the Catalans more harm than it would do to the Bavarians, especially if Barcelona used a higher build-up formation as expected – and that’s the way it was.

Busquets and Xavi sometimes seemed to be a little overwhelmed. Especially Busquets got stuck in the water. Fast dripping balls under pressure were more difficult. Another factor concerned diagonal balls from the centre to the sides. Xavi plays these passes best and can thereby shift the game. But this was problematic, as the middle seemed to be quite watered, and the sides less so.

Xavi had a hard time playing the soaked ball with precision from the deeper ground. In the air, the ball lost weight and came on faster. Precise passes were possible, but not perfect and easily processible ones – the attack was delayed. Bayern could shift and gain access to the opponent. Long balls from one side to the other are harder to play anyway and remain much longer in the air, which let Bayern shift better.

An additional factor was psychological. As playing across the centre was hard, and as there were no real passing options anyway, the Catalans orientated towards the wings – which Bayern, secure in positioning cover, liked to offer. They collectively moved to the side, engaged strongly and pressed. Balls won were the result, the consequence a counterattack. If the Catalans actually ventured to the front it could be dealt with as well: without Bartra and Piqué they are not dangerous enough to profit from crosses. Only set pieces created some danger.

Flat diagonal passes?

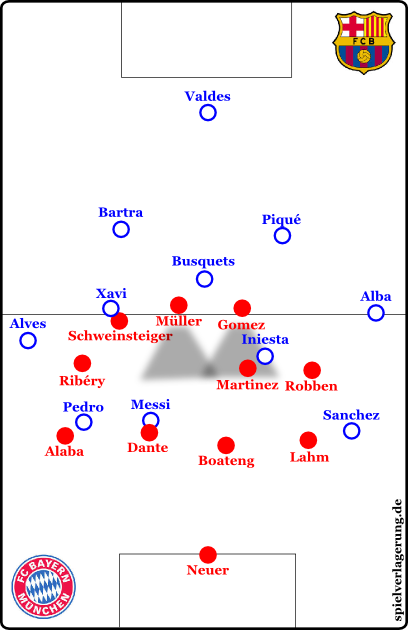

We have already discussed high long diagonal balls – but what did Bayern do against flat diagonal passes from the middle into half-space?

Bayern defended well against flat diagonal passes supposed to generate through balls – even without a watered pitch. In position-orientated zonal marking, they acted in a tight formation with the fullback on the far side of the ball. If a pass was played through this interface, the winger could simply move vertically to the rear.

Ideally, he intercepts the pass or deflects it towards the fullback behind him. In the worst case he takes the position of the fullback who in turn can push out and press. – Note: Here, the worst case is still a good one. But other options are possible. A few times, Ribéry moved to the back from this engaged position and used his covering shadow to cover both the interface and the opposing winger. The ball was then played with delay to the fullback. Barcelona was again on the wings instead of half-space and thus isolated from their usual style of play.

Also, Bayern had two other tactical factors on their side.

Bayern in a situational 4-5-1 (-0)

From a 4-4-2-0, Bayern again and again formed a 4-5-1-0 which was extremely variably designed. Sometimes it was Gomez whose backward pressing created strange effects and put him on a line with Martinez and Schweinsteiger. No problem here: There were less interfaces, and Müller took care of things in front. Then again it was Müller as well who fell back and created a 4-5-1.

Müller orientated himself also towards Xavi or Iniesta if needed. It was mostly due to Iniesta’s falling back. Müller then took over Martinez’s role and followed him back for stability. In a 4-5-1-0, Bayern could freely move from the formation without creating any gaps but generating new tactical problems for Barcelona to solve.

At the same the wingers were positioned wide but still with consistent, narrow interfaces. Space was tightened even more (bordering on the extreme) on the horizontal plane through isolations on the wings. In shifting, there were less open players for Barcelona. The Bavarian fullbacks then could continuously push out (otherwise it was “only” very often) and focus on the wingers.

The second factor in tactical defensive play was the way in which Bayern seemed to plan pressing moments.

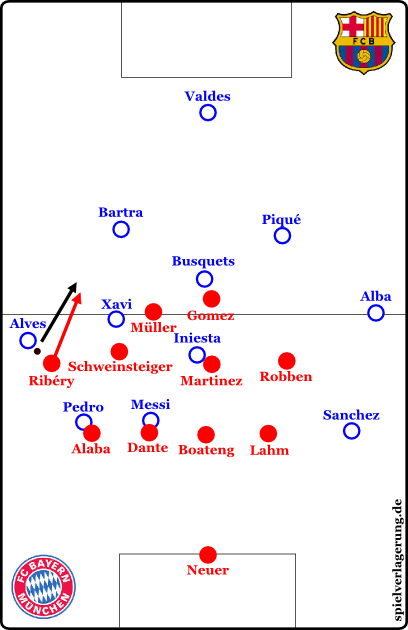

Framing and Hunting

Despite the position-orientated zonal marking, comparatively little ball possession and the 4-4-2-0, Bayern was anything but a purely destructive and passive team. They used the 4-4-2-0 to close down the centre and shifted back and forth. But if Barcelona came into this block (positioned up high), they were pressed out of there.

Bayern framed the Catalans with their movements, kept them in certain areas and pressed them out. If a ball came through into the middle, the network of surrounding players closed in, and Barcelona had to pass backwards. Bayern formed again. If the pass was inaccurate or sharp, they moved along and started to press. Barcelona then usually continued to play further back, albeit with many long balls to the front as well when pressure was too hard.

Ball on the side; Bayern starts hunting and engages. Ribéry presses, Alves plays back, Ribéry chases the ball.

Bayern successively gained space and remained in a 4-4-2-0. They forced Barcelona back by pressing the ball and the Catalan game out of their formation and sooner or later on to the wings. There they pressed, the Bayern defense block moved in horizontally and produced a lot of pressure – here again, passing backwards was a common Catalan practice.

On the hunt they pursued the ball a little while to actually force Barcelona back to the rear. Aborting a run is counterproductive – a loose pressing is not enough because Baracelona’s players are far too resistant to pressing. They would note declining pressure and turn. A pass may already have been played before the engaged hunter has reached his position. He must therefore hunt his “prey” until the end. Only in the event of a pass backwards the hunt is over – the basic position can be taken again safely.

In this, Bayern had almost perfect balance in pressing. They were successful in the counter-pressing as well, just because they practiced it less than on their best days. In contrast to normal pressing, one cannot create tight man-marking in counter-pressing. Counter-pressing takes place after losing possession, and thus space is inevitably available. A continous collective counter-pressing would have been exaggerated and too unstable against Barcelona. Surely they are too strong for that in their spatial anticipation, movement and pressing resistance.

Therefore, the Bavarian counter-pressing was less aggressive and dynamic. They rather focused on using it situationally and usually on returning to their basic positions to maintain stability as well as possible.

What did Barcelona do?

One might expect that Barcelona, with their individual quality and tactical group movements, would have found ways to counter Munich’s playing style, but they could not do it. Iniesta reacted to Xavi’s covering by falling back, but it did not yield any results. Pedro’s sporadic falling back in build-up play almost bordered on a joke – he was handed over in space and was completely harmless.

Messi received no balls in front. He was followed when he fell back into right offensive half-space and put into a cage. In right defensive half-space he was handed over in space and isolated on the wing. Alba’s pushing out and Sanchez’ engagement were handled as it was done on the right wing. An individually very strong defensive performance by Robben and Lahm’s general defensive perfection in positioning did the rest. There were only three changes in Barcelona’s play which were reasonably effective.

Semi-high passes and lobs were employed to circumvent Bayern’s hunting endeavours. In one scene the ball was simply lobbed over Ribéry, and the ball landed in his actual covering shadow and was received by the opponent’s teammate. But besides securing ball possession under pressure this created no added value, as it simply was not applicable to longer distances.

Ribéry puts Alves into covering shadow, Schweinsteiger fills the hole, Müller covers Xavi. Gomez runs at Busquets and tries to block the connection to the central defender if possible. But if Ribéry presses neatly, this isn’t even necessary. The ball goes to Valdes, and NOW Ribéry goes back to his position.

The second change concerned the forward movement of the centrebacks, as they had paths opened up for them. Piqué once ventured almost into the last third of the field without getting hassled. But even this tactical instrument was hardly used effectively, just as the increased fluidity of central Alexis and Pedro’s switch to the left wing.

Bayern’s adjustments were more interesting. Luiz Gustavo came in for Gomez and facilitated some gambling by Ribéry. They were also more flexible in switching to a 4-5-1-0, although the 4-4-2-0 with Schweinsteiger and Müller remained the standard version. Bayern countered more, played balls along the lines – and ultimately won.

Conclusion

What can I say about this game? I will not mention the performance of the referees. Other media will get riled about whether denied penalties outweigh more or less irregular goals. In my opinion, Müller’s action was probably the most intelligent and most effective foul in football history. Nevertheless, it was a foul. You cannot change it anyway. In my opinion, Barcelona was not as weak as they were in the first game against Milan, but not as good as they were in the second.

Bayern had better games than this, but very few. Tactically, Bayern was much better adjusted. Individually, they showed themselves to be at least Barcelona’s equals. Martinez, Schweinsteiger, Müller and all the others performed excellently …. What can I say about this game?

The article was written by RM, you can find the German original here. The article was translated by PF, one of our loyal serv… translators. We can’t thank him (and the other translators) enough for his/their outstanding work.

21 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

JR May 7, 2013 um 8:06 am

Not all fields are the same size. But even though it might look the other way around on television, the pitch in Camp Nou is actually smaller than the one in Allianz Arena. At least it was that way when the teams last met.

theonlyholmes May 2, 2013 um 12:41 pm

it is indeed. it was a mistake in understanding of mine.

theonlyholmes May 1, 2013 um 6:57 pm

bayern will be able to stretch out barca pressing formation even more on the camp nou field creating even more space, and havinf prople like Müller who ran nearly 11km in the last game, they could use this effectively. do you think having this bigger playing area suits the bayern team?

Trapattoni April 29, 2013 um 12:33 pm

Did you all realise what did happen in minute 71?

Substitution: Gustava in and Gomez out. And what happened? Bayern became more stable and even better in attacking. Two more goals for the bavarians within eleven minutes. Brilliant play.

BS31 could move more into OM and Gustavo was doing his defensive work.

So what to do in the return leg? Is that the solution already for the game at the camp nou?

In case Barca is pressing very hard Martinez supports the defensive line and makes it a 5-4-1 -supporting also the so called “cage for Messi”.

This is not cowardice but smart tactics. The moment the Barca side will realise this move they may inwardely think ” why do You make it so hard and difficult for us”.

What about the 6 bavarian players currently on a yellow card?

The problem is within the Barca squad: they are without Jordi Alba.

To bring in the trio Gustavo / Martinez / BS31 means that Schweinsteiger can move more freely and does not have to do the many tackles- so keeping him clear of receiving a second booking.

The last question to solve? Will Müller or Mandzukic start? Because of the long balls played by Neuer, Dante and Boateng it will be best to have a majestic receiver up front. That is of course Mandzukic. He will have to do the heavy work and in addition press on Busquets. By minute 70 he will be exhausted and exchanged by Müller.

A single goal by bayern will kill the competition- in that case Barca has to score 6.

Barca has a sky to climb that`s why bayern munich can make use of Trapattoni tactics in strenghtening defense and midfield.

Ball possession will be around 70-30 for Barca- but it will not really help them to reach the finale.

How many dives will we see by the likes of Pedro for example?

Here the link for people which do have a sense of humour.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qzfq2HxAkrk

Jacob April 28, 2013 um 7:21 am

what do u think about 2nd leg? , Barcelona will only push forward to get the goal early and pressure bayern to give in like they did it to Milan.

Bayern just need a one goal before 1st to make it easier to play the rest 45 min.

Having Manzukic will help Bayern more with pressing and defending.

Kaspar April 28, 2013 um 4:24 am

Man, die Detailanalyse der Bayern mittlerweile in Englisch aber immer noch nichts genaueres zu BVB-RM. Kommt schon Leute, das Rückspiel ist in den nächsten Tagen; )