Semifinals: France 1-0 Belgium

A game of two states. Before the lone goal of the match, it was a tactically dynamic affair with several notable aspects surrounding possession behavior, team tactical mechanisms in transition, and high intensity defensive executions from both teams. After the French took the lead, the Belgians veered from their original focus in search of an equalizer. France were able to absorb Belgium’s attack and earn their spot in the World Cup Final.

We previewed this matchup in the most recent episode of the SV Podcast, where the common discussion themes were about what manager Roberto Martinez could do to possibly gain an edge against the French. Considering Didier Deschamps’ team is so difficult to beat, several possibilities were mentioned about how to best them, and Martinez managed to somehow blend in all of them into the match.

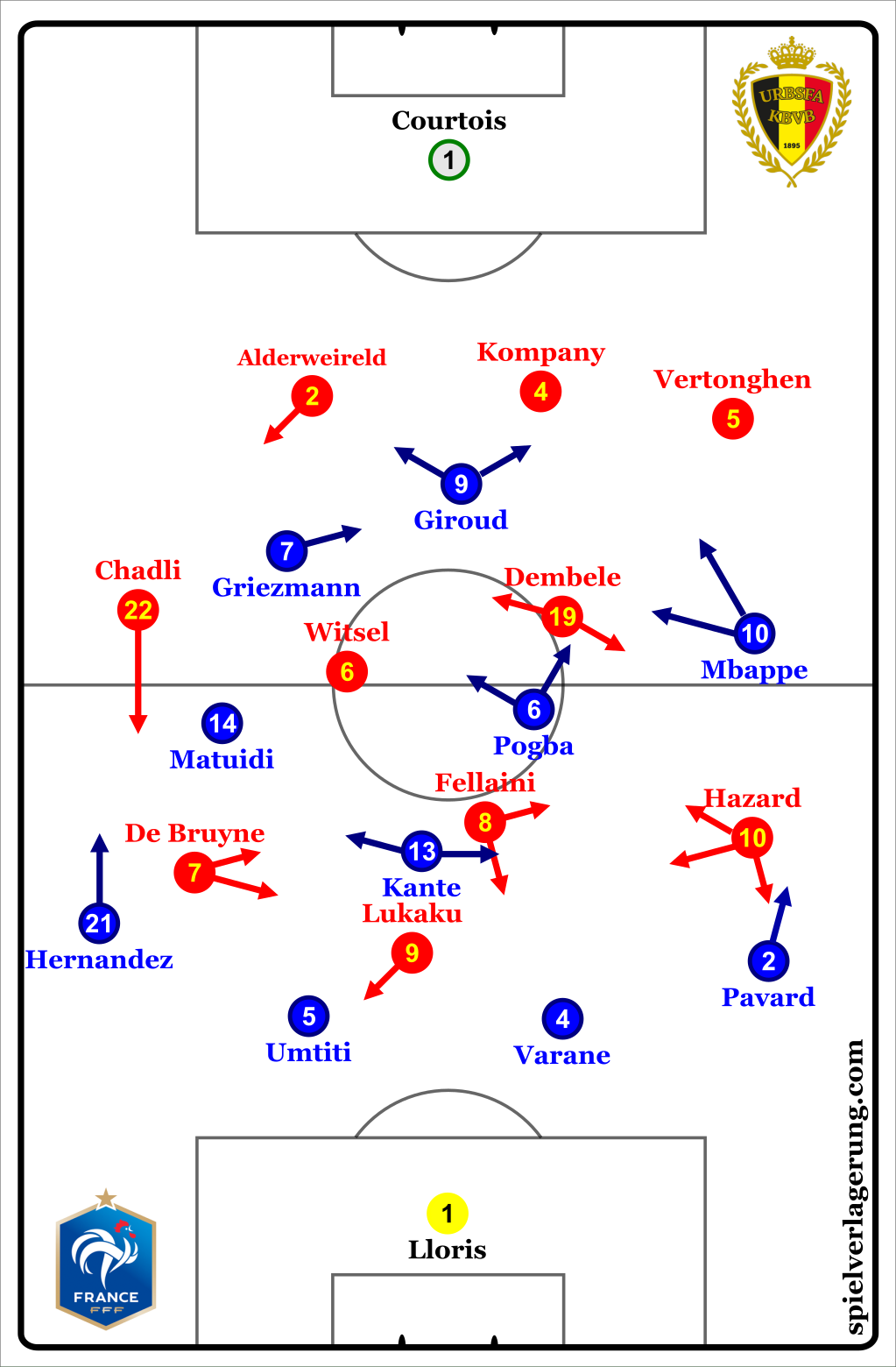

France have rarely made monumental shifts to their playing style throughout the tournament, with small opponent specific tendencies and alterations in midfield being the predominate adjustments from match to match. As expected, Deschamps set up his team around a stable focus in central areas, with transitions being a key focus of their attacking play. The one change in the team that Deschamps made was to insert Matuidi for Tolisso, continuing their hybrid 4-3-3/4-2-3-1 shape utilized throughout their Russian mission.

For Belgium, they made a couple of changes from their victory over the favoured Brazilians. Meunier was out of contention because of yellow card accumulation, causing Martinez to adjust his team yet again. In terms of names, Mousa Dembele was the only change. However, Belgium once again had a metamorphic system of play in this game. While in the last match it was a base of a 4-3-3, this match had a slight tweak into a 4-2-3-1. Nacer Chadli functioned as a makeshift right back, as Witsel and Dembele worked in a double pivot. Fellaini operated as a ten, doubling the aerial presence in central areas for the Red Devils.

Belgium shifts with the ball

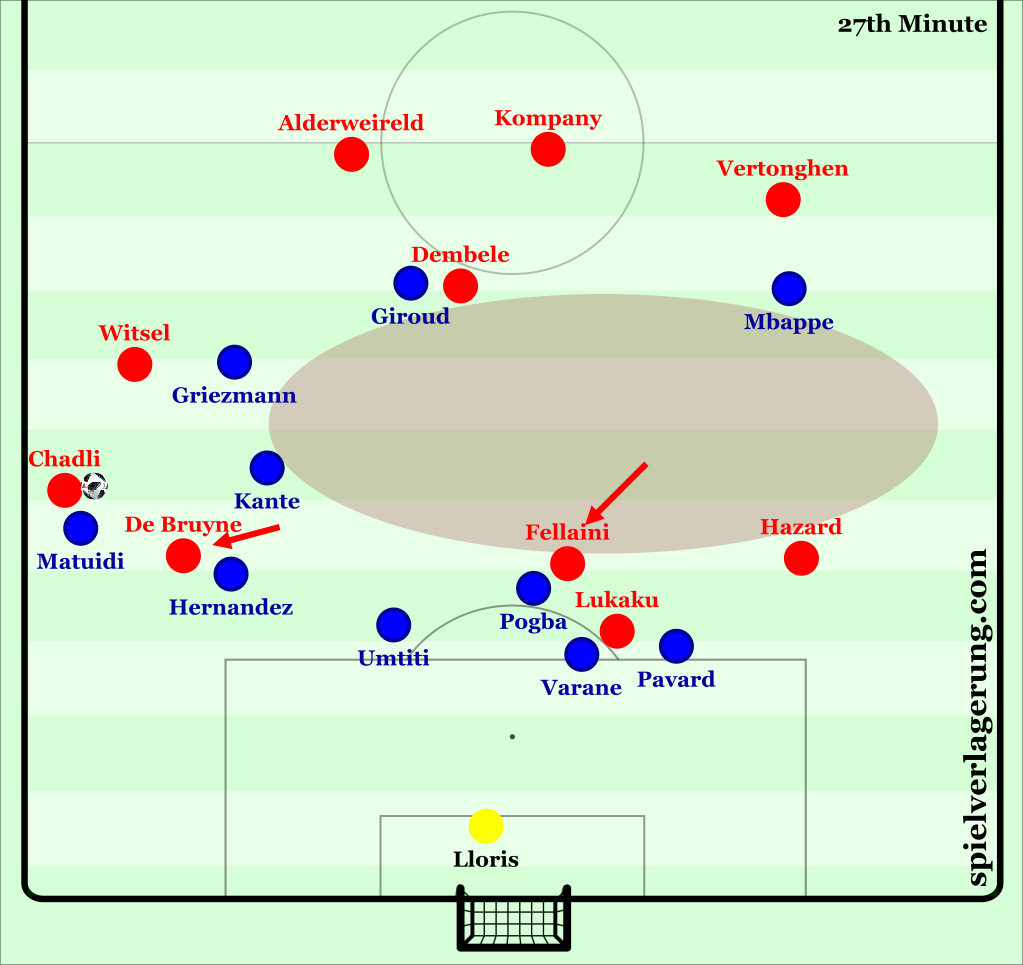

The most predominant feature of Belgium’s system throughout the match was the metamorphosis the team underwent in possession. Considering France were oriented in a passive deep block, Belgium were able to manage a majority share of possession and implement their noticeable shifts in possession.

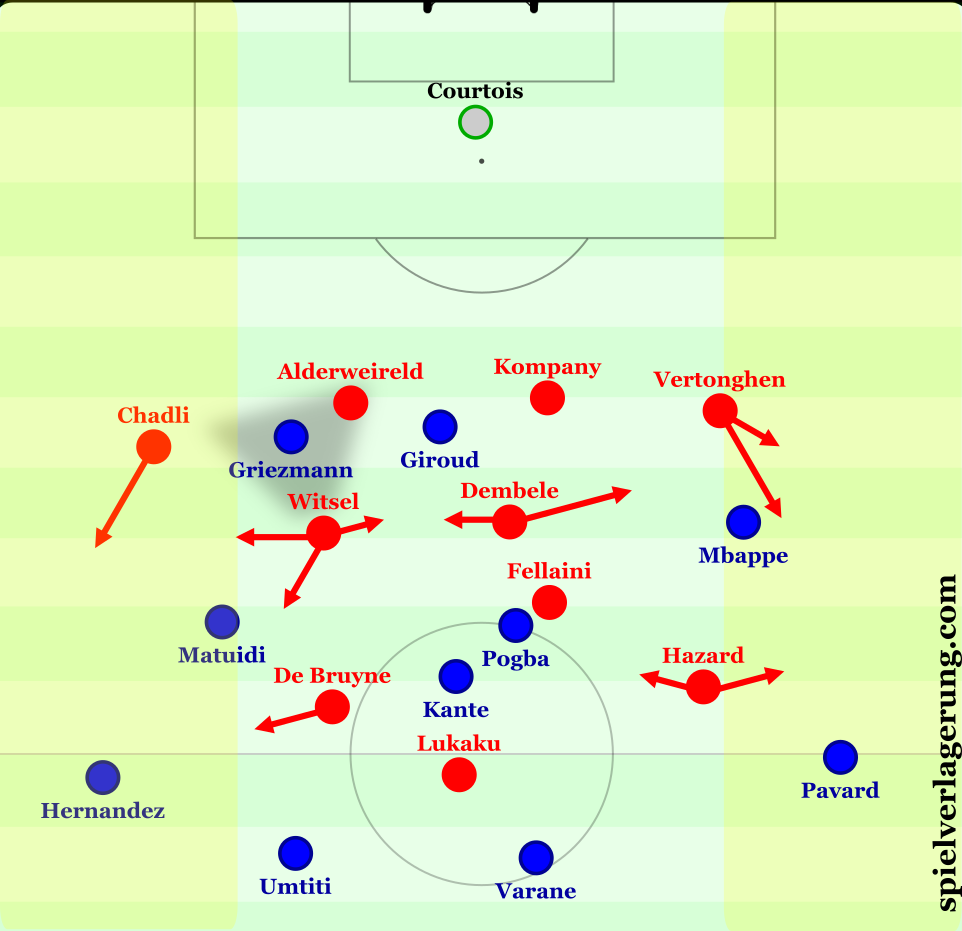

Belgium’s attacking shape worked as follows: Chadli moved high from his starting fullback position to occupy the right wing, with De Bruyne correspondingly moving into the right halfspace in the same vertical line as him. Witsel and Dembele occupied the spaces directly in front of the remaining three chain for central stability and horizontal circulation purposes. Fellaini mainly took up the left halfspace, venturing into the forward line when Lukaku roamed into the right channels. Hazard started out based on the left touchline. Thus in possession, a 3-2-4-1 formed with some small situational shifts which will be expanded on shortly.

With France’s deep block, the front three dropped off of the centre backs in preference of covering midfield passing options as opposed to proactively pressing during Belgium’s first phases. This 4-3-3-0 was heavily stacked in the centre of midfield, limiting the exposure to the ball of Belgium’s key players in highly beneficial areas.

As a result, much of Belgium’s attacks in the match were originated from the wings, each with a differing respective profile. Along the back line in possession, the superior distributors were the side backs of Vertonghen and Alderweireld, so in terms of their organization and progression of attacks, this development is logical. From the left side, Vertonghen was able to play diagonally toward the wing into Hazard, as France’s defensive positional focus was just central enough so that both Mbappe and Pavard did not have suitable access to Hazard when on the edge of the touchline.

Considering Pogba’s foreshadowing of the man-orientations on Fellaini in these opening stages, Hazard freely received these passes and progressed toward France’s goal through his exceptional dribbling, the most difficult task for France to contain on the night. Considering his decision making is world class when surrounded by multiple defenders, the onus was on Varane and Umtiti to cope with the subsequent actions that came after Hazard’s penetration, successful in their timing and application of clearances, even if it appeared precarious in the penalty area.

The right side of Belgium’s attack took a different disposition in terms of the collectivism of the tactics. Alderweireld more frequently dribbled out of the defensive line, causing Belgium’s attack to become predominately focused down this side. The circulation amongst Chaldi, De Bruyne, and Witsel against France’s passive block had considerable success when it was exclusively the three of them. With France wanting to press in the wings at first – Hernandez closed off the halfspaces in isolated situations to attempt to win the ball during individual duels – Chadli was able to get past Hernandez to put crosses into the penalty area. Fellaini then ran diagonally toward the centre to contest these crosses, which failed in execution but revealed Belgium’s early focus and tendencies.

Some of these attempts ended up with Hazard, who either recycled the attack or hazarded a scoring opportunity for himself. The early wing focus had the left side possess a more liberal means of progressing through the attack, with the right side being a bit more collective, yet still matching player strengths to the roles of the system well given the opponent.

France’s Learning; Belgian modifications

Despite the Belgian protagonism early on, France were able to make intelligent defensive adjustments in the flow of the match to counteract Belgium’s individual and structural potential. With Belgium’s ambitious on ball shape, they were able to commit more resources toward sequences in the final third of play, adequately covered thanks to a blend of France’s retreating and adequate occupation of each zone in attack.

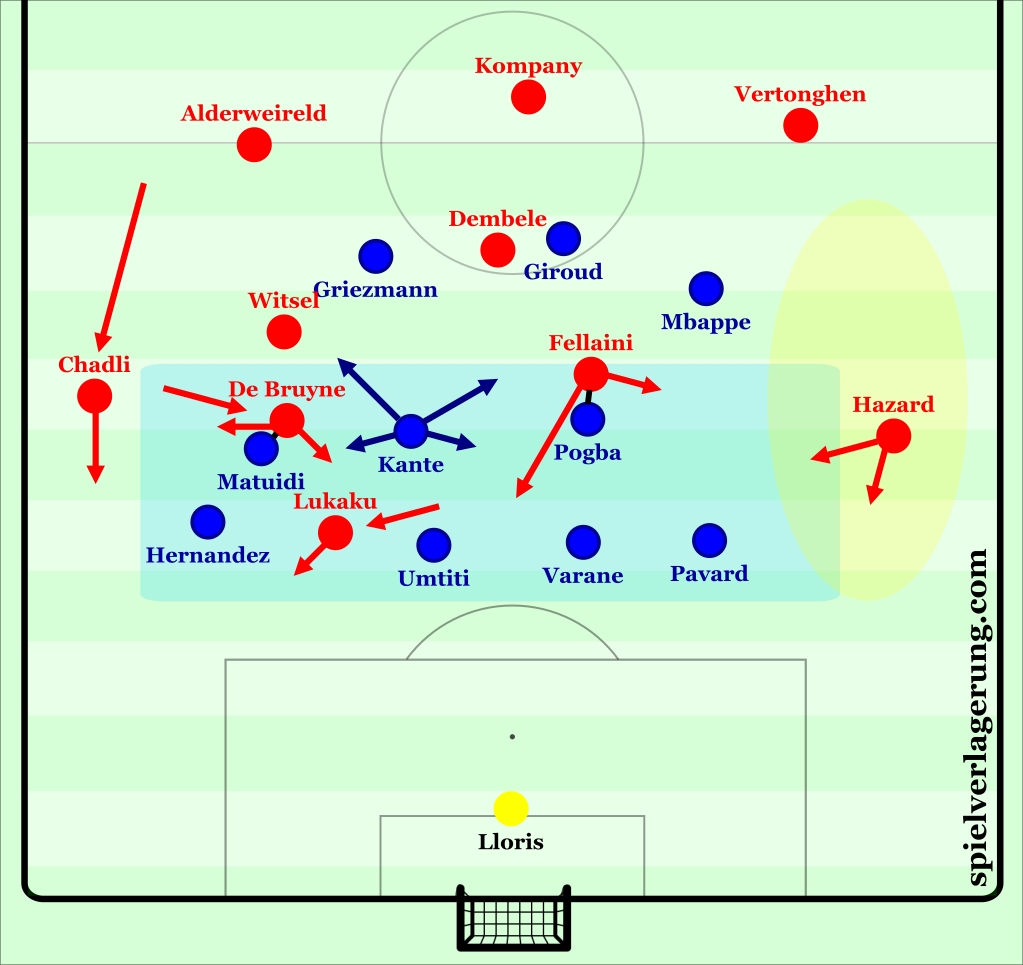

Yet as the half wore on, the focus toward the right side of play gradually increased, given the passages between players moved the ball further into France’s half. France no longer primarily focused in pressing in the wing spaces, recognizing that they could bait Belgium toward the centre through not only successfully intercepting passes, but also have multiple players able to pressure in those central areas to trap their opponents.

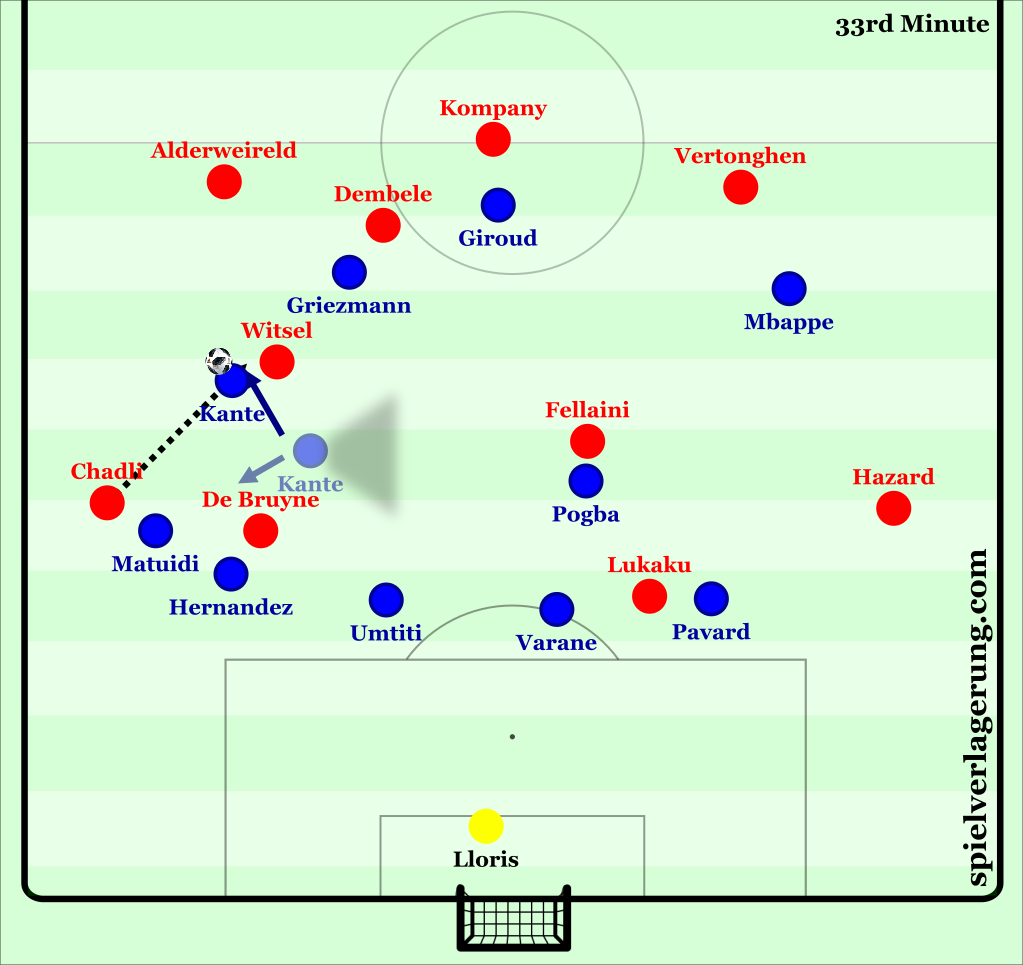

This situation increased in both complexity and difficulty to achieve as more players entered the right side for attacks. With Lukaku moving into the right halfspace as a possible bumper to the structure between Chadli and De Bruyne, so followed the man-orientation of Umtiti and a minor relocation of the remainder of the defensive line. This movement occurred as Hernandez moved to pressure Chaldi, rather than operating there as a starting reference. An action intended to promote combination play and more possible methods of breaking through France actually had the opposite outcome.

The introduction of Lukaku to the scene permitted Umtiti and France to increase the extremity of their ball orientation, thus restricting the space for Belgium to actually play with on the right section of the pitch. Matuidi from here functioned in a man-oriented sense with De Bruyne, and Chadli dealt with by Hernandez correspondingly. After Belgium’s bright start to In terms of circulation, this left Axel Witsel free to progress play or even switch the point of attack. Until Kante arrived.

As the half went on, Hazard began to take up these central positions with Fellaini moving wide left, presumably to get Hazard’s dribbling ability in more dangerous areas to fashion opportunities. A solution that could’ve worked for Belgium was to simply have Hazard move inside as Fellaini moved higher. Considering France’s already deep block, moving another player into the centre increases the demands of the auxiliary defenders joining from the attacking line, having to process more player interactions and more complex defensive interactions. Width could be generated through late movements from Vertonghen, running onto passes later as the ball is transferred from side to side. With the double pivot, four players would be adequate to defend in rest defense against most teams.

Oh wait, Kylian Mbappe. Makes sense now why Belgium wouldn’t implement such a strategy.

While Belgium’s attack started brightly, France were shrewd in how they adjusted both individual tendencies and group tactics to nullify their opponents. Belgium’s collective attacking was a mixture of ambitious and somehow stale, breaking down once they met the deeper layers of France’s shield.

Belgian Math: Minus the ball, adding in the centre

Considering all of the developments of Belgium in possession, their changes out of possession were equally impactful in the overall dynamics of the game. Chadli returned to the defensive line, with Witsel spanning the right halfspace and wing in territory. Dembele managed the area just behind Witsel alongside leftward coverage for Hazard, who (inconsistently) dropped centrally from the wing. Completing the puzzle, De Bruyne stepped higher to join Lukaku in situations where France preferred their left side to build up, getting Lucas Hernandez in higher positions in the process. Fellaini reciprocated the man-orienation applied onto him toward Pogba in the opening phases of France’s build up.

The ensuing picture for Belgium resulted in asymmetry in defense. It was 4-diamond-2 in some spells, 4-5-1 in others, 4-3-3, and so on. Regardless of the semantics, it was primarily concerned with a spatial focus on preventing passages into Griezmann to catalyze French attacks. Not to be overshadowed, another notable priority for Belgium was the pressing on the wings. Akin to their opponents, their narrow defensive structure provided ample space for France to pass toward their wide options.

Belgium’s defensive pressing movements with strategic emphasis on preventing Griezmann from receiving the ball and pressing toward the wings with support from the central midfielders.

Avenues were then available for the fullbacks to become more involved in attacking developments. From the centre backs, these passes into Pavard however were readily anticipated by Vertonghen, using the possession of fullbacks moving forwards as a cue to step up as fullbacks to intercept the ball in its flight if possible. Lucas Hernandez, superior in his timing of these movements, evaded these by starting runs later and moving into mixed spaces between lines during the pass rather than before it is played.

France’s attack composition, as unsystematic as it can be, followed the trendline for the last few matches. Pavard and Mbappe working in tandem on the right, with Hernandez being the primary source of width on the left. With these tendencies in mind, the Belgian central midfielders were instrumental figures to limiting the influence of these wide players. Dembele and Witsel frequently stepped toward wide areas as supporting pressure for the fullbacks to quell the dribbling of Mbappe and Hernandez respectively (or whoever attacked down the left side), who restricted their influences adequately in these situations.

Yet France’s attacks were not primarily composed from these build up situations.

Transitional Tactics

The most interesting aspects in the match from both teams came from transitions. France have been one of the top international sides throughout the past couple of years in attacking transitions, with Mbappe headlining their counterattacking efforts thanks to his remarkable acceleration and sprinting speed in behind. From Belgium’s perspective, their quarterfinal win against Brazil displayed their counterattacking potential in an unorthodox tactic, where Lukaku functioned as an inside right forward. Yet it was the defensive mechanisms for each team that stood out, France on a high note, Belgium less so.

Belgium’s rest defense as shown in the graphics above was comprised of the back three with Dembele and Witsel staying in front of them. During Belgium’s building, the back three would step up as a unit at times if they felt the space between them and the duo in front of them was too high, mixing an element of compactness into their attacking structure with transitional defense in mind.

Despite this stability that comes with the 3-2 structure, France were still able to break through on the counter for a multitude of reasons. Both Witsel and Dembele each took up suboptimal distances in their rest defense in relation to each other, leaving a sizable space centrally for players to run between and pick up the ball. This originated from one of them moving toward the wing to pressure the ball without the following shift, leaving France’s attackers with space to break.

France’s counterattacking was also boosted because of their organization in their deep block. Since players were so close together in their compact shape, once France won the ball, they had more options nearby to navigate Belgium’s counterpressure. France could play quick passing sequences and beat their opponents through these spaces, taking advantage of Belgium’s spotty intensity from players that were far from the ball during transition.

Lastly, the ability for France’s dribblers to break through the initial counterpressing was integral to their success in going forward during these moments. In the instances where Pogba, Kante, or Matuidi were able to resist the first pressure players, Mbappe and Giroud were able to move beyond the defense and push them toward their own goal. After these players were beat, they subsequently had more space to move into and attack, leading to several promising counter attacking opportunities during the match. After three high potential counters conceded, Belgium was resorted to solve this situation through tactical fouling, unable to contain the individual qualities of France’s players on the break.

By the same token, Belgium’s counterattack was contained remarkably well by the French. With France’s attacks, they forced Belgium closer to their goal as Belgium committed more players to these defensive stages, making rest defense much simpler from their point of view. Since Lukaku was the only player left high, it was the two central defenders and Kante against one, a situation that Uruguay struggled to solve during their encounter in the prior match.

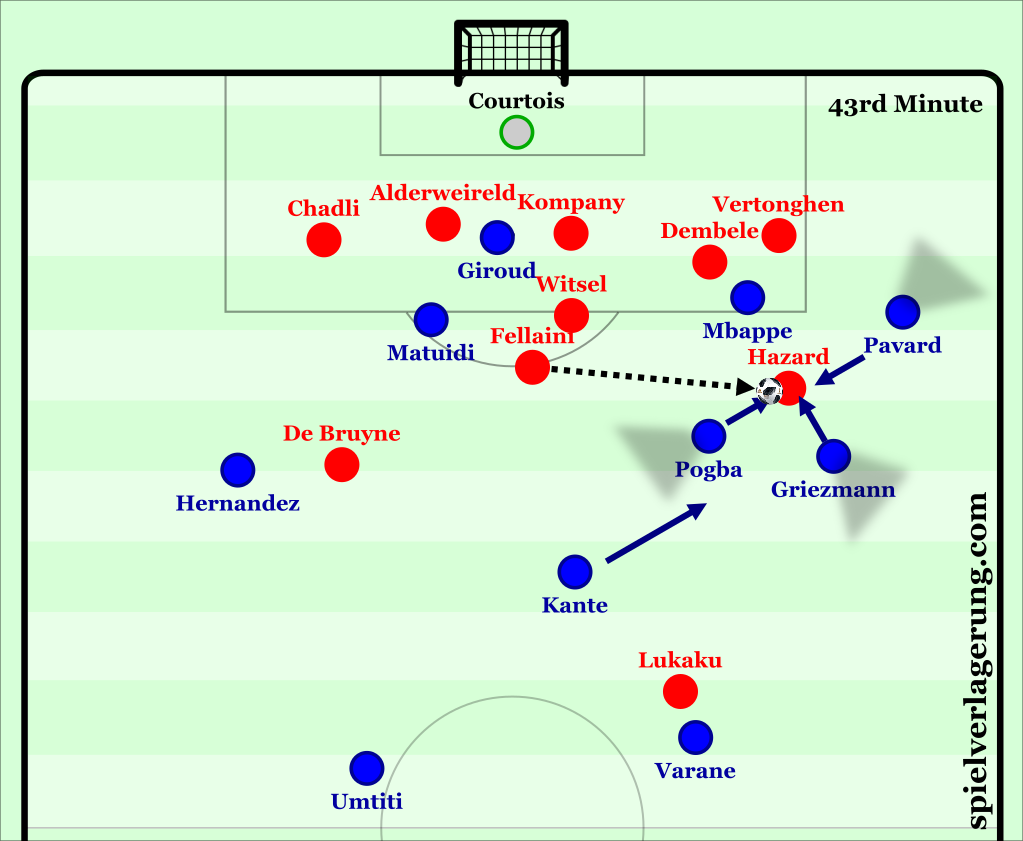

France’s counterpressing was also a marvel in its own right. They were remarkably fast to apply pressure to the ball in the first place, yet finding a great balance between getting players surrounding the ball and cutting off possible passages out through their cover shadows. Paul Pogba, in a consummate overall performance, was the standout player for France in this component. When also supported by one or two attackers higher and Kante behind, even the most talented players in the world would not be able to protect the ball.

One example of France’s counterpressing, in which even the skillful Hazard can not make his way out of this situation.

Belgium were a step slow in providing the supporting angles from more distal players as the French initiated their counterpressure: too frequently did players have to dribble out of situations that are really hard to get out of on their own. The overall level of responsiveness was not high from this Belgium team in these transition phases, with only the front three being active in their movements to provide any sort of help. But France were savvy to apply heavy man orientations on the nearest Belgian player as the rest of the team counterpressed, so even if they were able to escape the first bit of pressure, France could anticipate the next pass and possibly intercept it or retrieve the ball if it there was a technical error.

In was in these pivotal moments that France created a palpable quality difference in terms of their team tactical implementations. While this match was interesting in that both teams counterpressed very high up the pitch, France were much superior in the organization and application not only in their attacking through Belgium’s initial pressure, but also in the defensive moments of the match that were crucial to limiting the Belgian star talent.

State Change: France Gain the Edge

Minute 51 saw a fundamental shift in how the match was played, as Samuel Umtiti nodded away a corner kick to register the only goal of the match. Prior to that, there were a series of interesting developments that would’ve been interesting to see play out over a longer duration.

Belgium swapped the positions of Hazard and Fellaini more vividly at the start of the second half, bringing Hazard to the ten as discussed earlier. However, with Pogba intensifying his man-orientations onto Fellaini, Belgium’s attack appeared promising to get Hazard into more influential spaces. In addition, Hazard’s deeper positioning would better preoccupy Kante in France’s defensive structure, preventing his Chelsea teammate from chasing the ball at such a high rate, and thus limiting his potential influence on transitions and ball recoveries for his side.

But after France’s goal, they began to possess the ball more defensively and enlist further help toward the defense of central zones, thus reducing some of the novelty of the Martinez adjustment battle. In the first hour, close chances that were of considerable difficulty, yet almost converted, were counteracted by Lloris. With the chips down, Martinez decided to alter his team’s strategy in hopes of squeaking in an equalizer after failing to do so for the first hour.

Belgium last hopes, France time management

With the introduction of Dries Mertens, Martinez altered Belgium’s structure from the 4-2-3-1 base found in the first hour of the game to a 3-4-3. Mertens entering for Dembele, pulled De Bruyne back to right centre midfield, and Chadli was pushed ahead to the right winger in the front three line. Fellaini and Hazard each found themselves in wide left spots, with Witsel now being the source of stability between them.

Considering the personnel, the roles of each of the players were somewhat of a surprise if it were a normal circumstance. Mertens on the outside right was tasked with whipping in crosses toward Lukaku and Fellaini, alongside Kevin De Bruyne having the same function from his inside right position. In the way that the first half saw the right side be a beacon of Belgian combination play, it suddenly converted to the source of directness for the whole team. The team was frantic and impatient with their decision making, with Martinez urging his players to relax at regular intervals. Their team identity was gone in a flash, suddenly blazing with long shots from centre backs and midfield movements carved in personal instincts rather than any sort of positional blueprint.

With France’s ever so disciplined unit in defense, Belgium’s team became more fragmented as injury time beckoned. As Giroud and co. focused more and more defensively, the likes of De Bruyne could not manage much of the ball in higher lines of the field, so they dropped back to retrieve the ball from the defense and playmak. This tendency exacerbated as time went on, eventually creating a sharp division between players attempting to remain in the positional blueprint and those abandoning the plan to do whatever they possibly could for themselves to get into the final.

France were able to absorb these moments of slight promise of the Belgians, without making any substitutions in the process. A puzzling change that Martinez made with around fifteen minutes left was taking off Fellaini for Carrasco, presumably to provide another dribbler to perhaps unlock the deep block after seeing the aerial efforts not work. With close chances on set pieces and some France defensive shifts, the final stretches of the game were standard and predictable given the strengths of Belgium’s physical players, the collective strength of France to not concede in the tournament once in the lead, and Martinez’s propensity to play more direct when his team is losing in elimination settings.

As for the French time wasting toward the end of the match, it has been an integral part of their campaign so far. Don’t hate the players, hate the game.

Conclusion

Belgium didn’t lack a Plan B. They weren’t good enough with their Plan A to beat France. The end.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Zaropans September 23, 2018 um 9:40 pm

Quite liked https://www.theguardian.com/football/2018/jul/12/didier-deschamps-france-world-cup-final-belgium#comment-118186685