Examples of pressing traps in the 4-1-4-1

This article describes three ways to build a pressing trap when transitioning from a 4-1-4-1-defensive formation into the press.

A pressing trap invites the opponent to act in a specific zone in their formation. This becomes more difficult if the defensive formation isn’t modified while pressing, because you can’t open any gaps without making your intentions known to the opponent, or you become unstable when trying to close the trap because of a lower Dynamik.

The 4-1-4-1 allows for simple transformations into different formations, with several possibilities and variants. These changes create a greater Dynamik, which can be used to open certain gaps and allow the team to quickly close down and snap the trap shut. Let’s begin with one of the most common variants.

The 4-1-4-1 becomes a 4-1-3-1-1/4-1-3-2

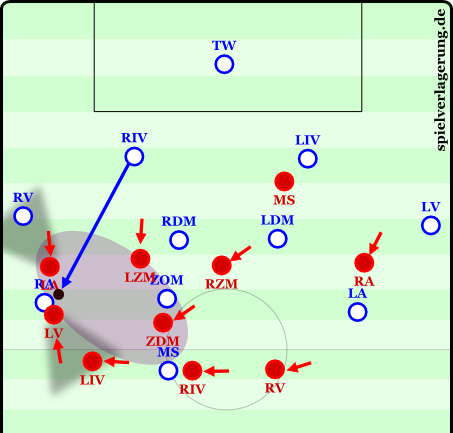

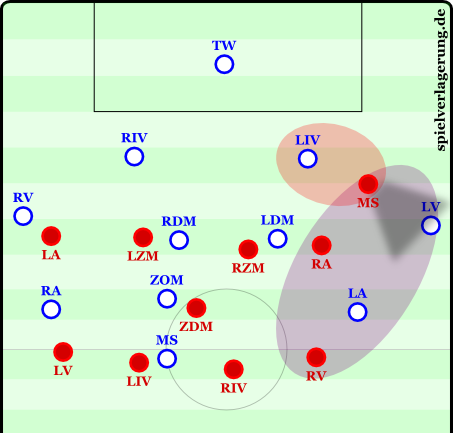

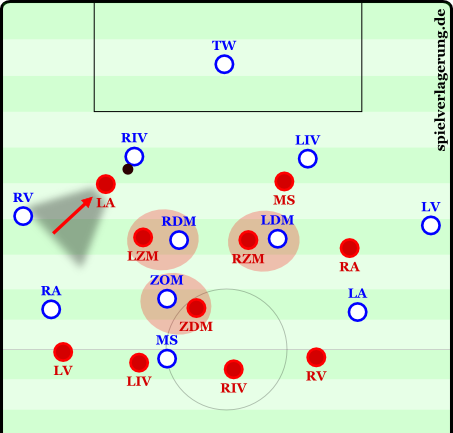

In this situation, we assume an Angriffspressing (pressing from the forwards). At first the team orientation, despite the height, seems passive. The 4-1-4-1 is position-oriented and the centre forward is the only player focused on man-marking one of the center backs. The other center back is deliberately left open.

Once the ball comes to the free center back, the Achter (eight) moves up to press him. The striker man-marks the center back or can leave him in his cover shadow, depending on later following mechanisms. If, for example, he drops back diagonally, he still has access to the center back but can also help out in the middle. The central defender might, in some circumstances, run free on a backpass to the goalkeeper.

The center back should be pressured in such a way that he can still rotate, but immediately after the rotation, is under pressure. Thus, he can not play back and is forced into errors. The central defender is – especially if he is right-footed – under pressure and can only play a difficult pass forward. The winger moves up on the fullback and also stands slightly further inside to make the subsequent pressing trap more effective.

Now, the center back has to play a long ball. Due to the pressure and, ideally, a slightly arc-like run from the advancing central midfielder, a precise diagonal ball is nearly impossible.

This aspect, together with the open space in his field of vision, should normally force him to pass into the open hole. But, he falls into a trap.

The winger who is furthest from the ball may fall back and inside to allow the second central midfielder to indent; this will create more local compactness and more Dynamik. Also, there’s a reason the remaining central midfielders are slightly asymmetrical. They can, on the one hand, create horizontal pressure on two different levels, and, on the other hand, have the opportunity to react to specific events from the opponents with greater Dynamik.

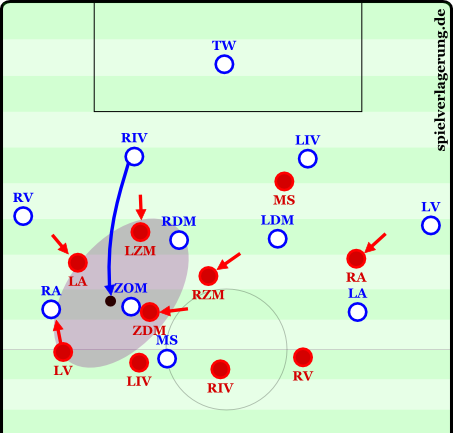

A long ball is played up the wing, the central defender (LIV) moves out, the other players move over. Depending on the development of the situation, the six (ZDM) can drop back, if necessary.

If the pass cuts through the middle, the six can fight for the ball with better momentum. He plays very vertically in the hole so that the center back can move out and allow him to drop into the back line.

On a pass along the wing the six can also allow the fullback to move out. As soon as the opponent stops the ball, he is surrounded. He is pressed from all sides and nearly every passing option lies in the cover shadows and the advanced Achter (eight) can also participate. It is very, very difficult to find a way out. Just receiving the ball could lead to big problems. Theoretically, you could refer to this as a gegenpressing trap.

A long ball into the middle. There is a local compactness, with six players available to press the opponent.

The asymmetry of the remaining midfielder has also another purpose. Staggering in a 4-4-2, would result in either a 4-4-0-2, 4-0-4-2, or a 0-4-4-2; there would be a large hole somewhere, because the entire horizontal path would be free. The cover shadow would immediately lack the ability to prevent a lateral ball from the opponent, resulting in new situations and passing angles. With second balls they would also not be compact, and during outward moves the defenders would be vulnerable to long balls and deep sprints.

The second variant of a pressing trap is similar, but opens space elsewhere.

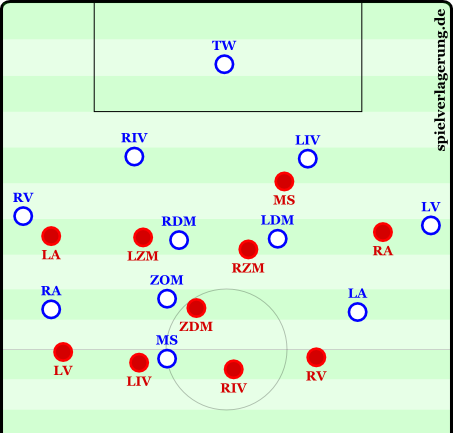

4-1-2-3 with asymmetric wingers

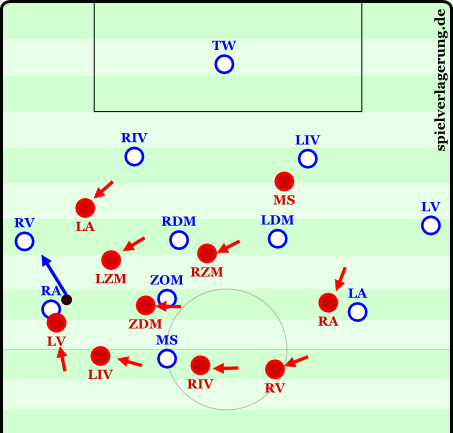

This situation is similar to the basic formation, however, this time one of the wingers attempts to establish access to the other center back. Here, the winger puts the fullback in his cover shadow while he pressures the central defender. The two Achter (eights) now move in the direction of this side of the field and control the space while the six secures and acts almost on a level with his two center backs so that they can move out on long balls.

A forward pass is not really possible and if a diagonal ball comes, the entire formation then pushes across towards the other side of the pitch and isolates them there. The middle is protected by the three midfielders. Their position-oriented playing style in the middle keeps them very compact and allows them to isolate the wide players, while the fullback and the backwards pressing winger can set aside their pressing. The trap is created through this isolation: if the opponent passes to their near-ball winger, then the Achter (eight) and Sechser (six) will already in a position to restrict space.

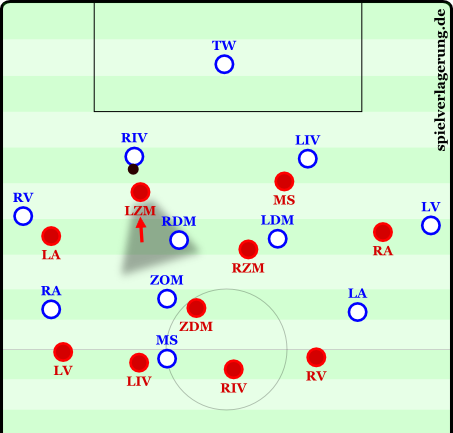

Here the ball comes to the right winger (RA), who is immediately isolated, but has an open option; his right-back (RV), for a direct drop.

The full-back is forced back up through the hole, but then is almost completely isolated. The entire formation pushes over. The six (ZDM) backs up the intermediate line area and the winger (LA) can aggressively press in conjunction with the eight (LZM). Passes into the middle or on the wing should be almost impossible or must go in tight spaces, making turnovers likely.

The right-side defender (RV) has no passing options, moves further up the pitch with the ball mostly at his feet, and is then caught against the sideline. The left winger can now use the open space behind the fullback to launch the counter. Bayern has done this several times this season.

If the center back sends a long, diagonal ball to the far side, the center forward is there and can orient himself on the Sechserraum (six space). Because of the length of the pass, the formation can also move over and there is usually no time for the winger there to deliver the pass, just like in the near-ball variant of pressing the opponent’s buildup game.

This pressing trap is less intense and flashy, but works in a similar way, while at the same time having interesting advantages in offensive Umschaltspiel (transition); FC Barcelona, as well as Guardiola’s Bayern, have practiced both methods several times this year. Another interesting variant has also been seen this season.

The centre forward as a hunting wedge striker

Many teams use a 4-1-4-1 with a relatively static “wedge striker” who drives between the two central defenders, to sever the connection between them. He then runs up to the pass receiver and redirects the build-up play from the opposition into a direction where his own team can arrive sooner and in greater number, which means more local compactness. In this variant, there is really no pressing trap or change in the defensive formation.

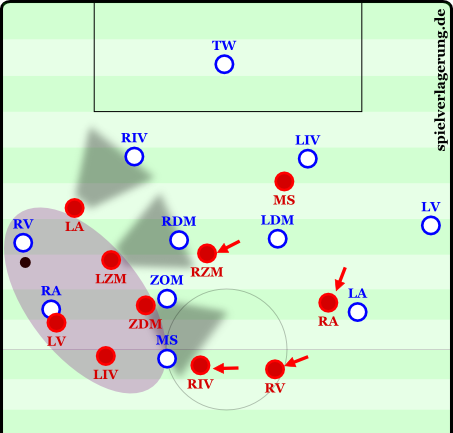

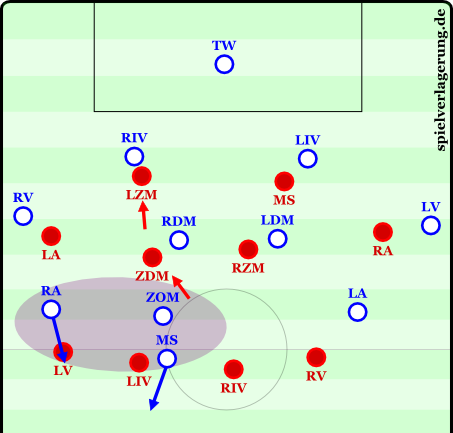

However, you can create a pressing trap with a wedge forward, if he starts from a wide position. There, the displaced wedge forward – e.g. Messi against Rayo – can focus on the opposing fullback. He leaves both central defenders free and man marks the full-back. The opponent now has a certain problem in their buildup.

The displaced wedge striker has the full-back (LV) in his cover shadow and at the same time has access to the center back (LIV). This is pressing trap #1. Pressing trap #2 is the open space behind; a long ball can get to this space but if often results in a 3 v 2.

The central defender near the wedge striker can not play down the wing. The full-back is already man marked, a long ball is not an option, and a refusal to play on this side makes their offensive game extremely easy to figure out.

By ignoring one side, the opposing wingers can constantly move back – or into the formation, thereby providing either stability with long balls into the intermediate line space or more pressure, which is a plus for this style of play. When moving inside, for example, the two eights can produce high compactness and prevent passes into the Sechserraum (six space). This can also be practiced when the central defender near the wedge striker gets the ball.

When this happens he must play the ball, at the latest, to the other central defender, who can be easily run at again by the oncoming centre forward; this one move can take three players out of the game when run properly and produces very high compactness, if properly implemented. This compactness requires excellent coordination in its movements, however, and can take also a large toll.

The route is very long for the striker and may exhaust him. At Barcelona, Messi did this in only a few games (usually during a draw). He didn’t sprint but was in more of an intense run and generally only did so at the end of an aggressive move up from the rest of his team. A consistent implementation of this style of play may well be impossible.

Conclusion

Caveat: Theoretically, there are an infinite number of possible pressing traps and ways to arrange the positioning of the team to create them. In any formation, Pressingfallen can be generated from different positions and pressing runs. The 4-1-4-1, because of its potential movement and its use in a high press, has some interesting features which have been described here in three variants.

Generally, it is important to know that Pressingfallen exist and are used. Jürgen Klopp said he set these traps up against Real Madrid, which ultimately led to one of their successful counterattacks. So, our advice is: don’t always, if space is opened against a team, assume that it is due to poor movement. Sometimes . . .

Thanks to @rafamufc, who translated this piece for us!

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

T ryan April 16, 2015 um 6:28 pm

Great article and explanation thanks for posting this!

Will use these ideas in training this week with my squad 🙂

trilogy February 25, 2015 um 9:49 am

Very good article about 4141 formation.

Could I use this article in my blog ? As I am Gooner, Your article gives a insight about our team formation.

http://blog.naver.com/sniperlsh ( My blog site, Just for study. )