How Stuttgart went from a relegation candidate to the Champions League in a year

Sebastian Hoeneß took over VfB Stuttgart in spring 2023 as bottom of the table and led the club to relegation. Just under a year later , Stuttgart qualified for the Champions League for the first time in 14 years.

By Danilo Kupke, former assistant coach for Werder Bremen’s under-16s and former analyst at Union Berlin’s academy

Stuttgart once again emphasises possession football under Hoeneß (57 % possession the third best value in the Bundesliga). VfB are currently exciting the Bundesliga with their many playful solutions and tactical tricks. Defensively, Stuttgart stand out with their courage to take risks and their high, aggressive pressin g. In the following analysis, three factors for Stuttgart’s certainly not coincidental success are presented.

Variability in the build-up game

The first factor Stuttgart looked at is the great variability in the build-up play. The high degree of variability causes constant problems for the opponent in the pressing. The full backs play a decisive role in this variability.

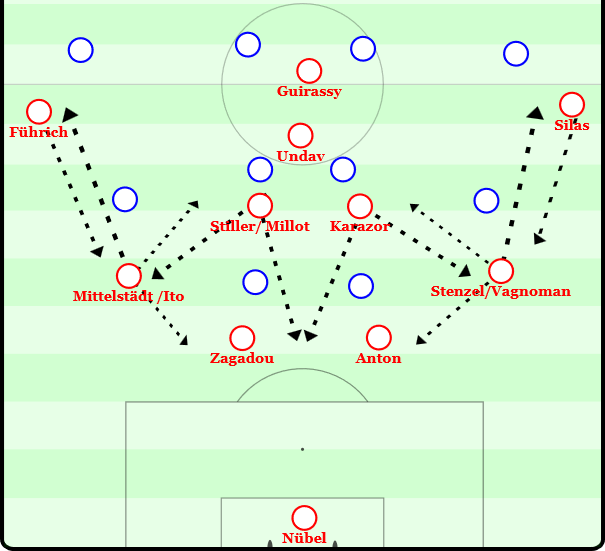

Stuttgart’s starting position is usually a 2-4-3-1 as shown in the graphic. The two outside midfielders use the entire width of the pitch and are therefore the only players to occupy the outer lane at Stuttgart. Undav becomes a number 10 when playing with the ball, while Guirassy occupies the full depth. Under Hoeneß, the wingbacks are only simply occupied, as the aim is to pull apart the opposing team’s defensive chain. Another advantage of the tighter full-backs is the greater compactness and the lower risk of running into counter attacks if mistakes are made. In addition, counter pressing becomes more effective as the distances from the centre are significantly shorter.

Stuttgart have different types of players with Mittelstädt or Ito as left-backs and Stenzel or Vagnoman as right-backs. Both Pascal Stenzel and Maximilian Mittelstädt have played in the centre of midfield several times in their careers. Hoeneß is utilising this experience. As can be seen in the graphic, it is always possible for a full-back to push up into the central defensive midfield and overload the centre as an additional number 6. If a full-back pushes inverted into the centre, the other full-back usually drops back and forms a back 3 with Zagadou and Anton. Stuttgart then build-up in a 3-3. If Stuttgart play with Mittelstädt and Stenzel at the same time, an additional option is for both full-backs to push up into the centre at times and Stuttgart build up in a 2-4. This unpredictability constantly causes problems for the opposition, at least for a short time, which leads to Stuttgart finding a free player in the build-up play.

In addition, one of the two 6s (usually Karazor) often drops off against 2 pressing strikers and becomes the third central centre-back. Switching the positions of one of the 6s with one of the two full-backs is an additional option.

Especially against teams defending in a 5-man defence, Stuttgart use the change of position between the full-back and the outer midfielder to open up space on the wings. In the graphic above, you can see how Dortmund operate against the ball in a 5-4-1. As Dortmund keep the centre compact and the two dropping strikers Undav and Guirassy are taken up by the outer centre-backs, it is very difficult to create space in the centre. Dortmund’s full-backs are clearly man orientated against Stuttgart’s outside midfielders. This allows them to be pulled out of their positions. Vagnoman, who also feels comfortable as a right midfielder and is very fast with a top speed of 33.96 km/h, can perfectly occupy the free space created by Millot’s dropping off. Just as Anton receives the ball, the change of position is completed. Ryerson and Bynoe Gittens are faced with the question of whether to hand over to Vagnoman and Millot or go with them. This question is further complicated by the fact that Vagnoman is moving in the half lane and Millot is moving in the outside lane. If both were to swap positions in the same lane, passing the opponents would be the most effective solution. Ryerson hesitates to go with Millot first, giving him more time and space when Anton passes to him.

Bynoe-Gittens looks to the ball for a brief moment and thus loses sight of Vagnoman, who is then in the marked area for a longer full stop of time and without opponent pressure.

Another option against simply occupied wingers of the opposing team is to overload one side in the build-up play.

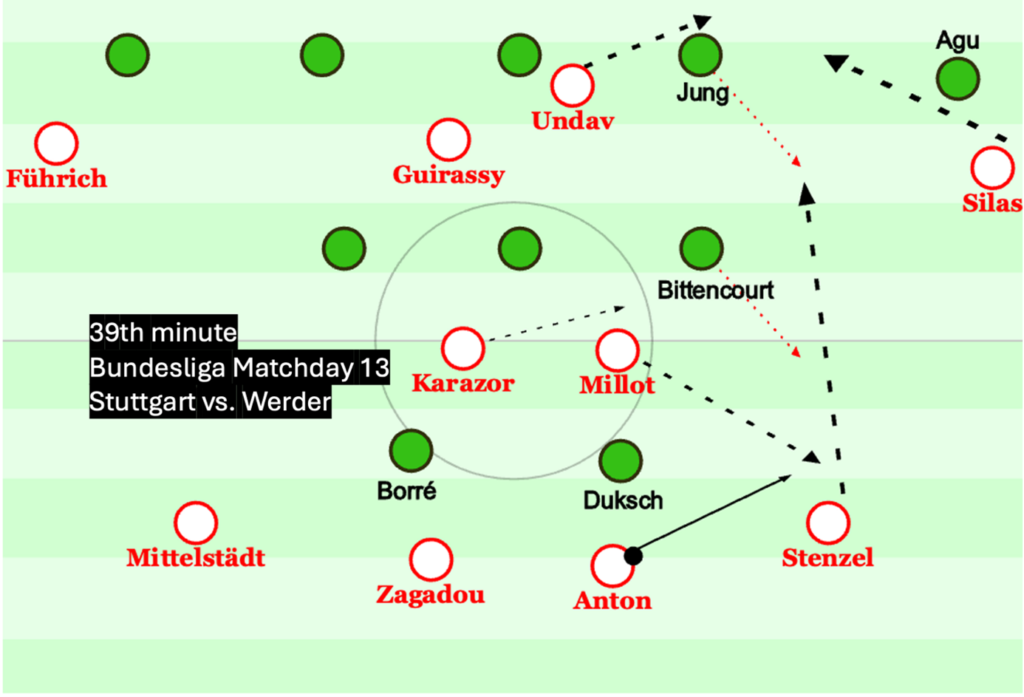

Werder defends against Stuttgart in a 5-3-2, with the focus once again on compactness in the centre. Millot becomes a right-back, while Stenzel shifts up to the right side. Silas does not change his position. As a result, he ties down Agu. As soon as Millot is played on, Bittencourt has to shift out of his central position and can no longer cover Stenzel. The freed-up Stenzel is then played on by Millot. As a result, Werder’s left centre-back (Jung) has to move out of his position. This opens up a large space in Bremen’s final third. Undav or Silas could run into this space. In the meantime, the left-sided number 6 Karazor has been pushed into the free space (where Bittencourt is missing) and therefore acts as a new, further option.

Stuttgart manage to utilise the strengths of the different types of players effectively in their build-up play. They have a very good positional game, through which they have solutions against all systems at all times in order to enforce their build-up play and potentially utilise the spaces offered by the opponent. Their unpredictability makes it very difficult for opposing teams to close down all spaces at all times.

Constant activity & overloading of the midfield

Especially after the build-up play, VFB Stuttgart tries to play flat passes through the centre and prepare attacks. It is noticeable that all players are active at all times and repeatedly offer themselves in the centre lane or the half-spaces. Undav overloads the opponent’s midfield with his constant dropping and thereby creates an overload in midfield.

In addition, one or both of the outside midfielders will repeatedly drop into the centre. Another option, which has already been described in the section above, is for a full-back to shift into the centre. This allows Stuttgart to constantly create an overlap in the centre of the field.

However, Stuttgart occupy the centre with a clear plan. They have a staggered formation at all times, which makes it possible to create different levels with different angles of attack. The different levels and angles make it much more difficult for opposing teams to defend everything. With patience, Stuttgart very often find the free player in midfield who can then initiate attacks.

The graphic shows how Undav and Millot overload the centre. Millot moves from his position in right midfield into the centre. At the same time, Vagnoman moves forward from the right-back position, thereby tying up Ryerson. Bynoe-Gittens no longer has a direct opponent and simply covers the space. Özcan and Sabitzer defend man-orientated against Stuttgart’s number 6s (Stiller and Karazor).

Undav and Millot are in the centre without any real opponents, as the centre-backs would only move out when the ball is played.

However, this would mean that Millot and Undav would have enough time to combine. Wolf covers Führich at right-back, who is initially very wide and at the height of the halfway line. He decides to move into the centre. Wolf initially goes with him, but then passes Führich to Adeyemi.

This creates a double superiority in the centre for a short time. Stuttgart did not use this, but would have had several opportunities. Führich could have taken the ball with his first touch and played it to the free-standing Millot. However, Führich’s backpass to Anton was also a good option, as Anton does not have much pressure on his opponent and, in addition to Millot, there is a new passing option with Vagnoman (1v1 on the wing against Ryerson). Stuttgart didn’t play the freed-up players, but, as in the whole game and in the season so far, created overpayment situations in a very dangerous zone. Dortmund only had to react when defending throughout the game instead of being proactive. In addition, Dortmund were never able to implement their plan and close down the centre due to Stuttgart’s constant overloading.

Dortmund had to find ways to reduce the deficit in the centre without offering space on the wings. Führich’s tipping off is a good scene, as Wolf briefly goes with him but then hands over to Adeyemi. Wolf doesn’t want to go with him, as otherwise the winger would become free. Mittelstädt would most likely move up and would briefly have a lot of space and little pressure from opponents.

The high level of activity of Stuttgart’s players and constant changes of position are also noticeable in Stuttgart’s wing play.

While most teams with a back four try to create short-term 2 v 1 situations with the help of the full-back and the outside midfielder on the wing, Stuttgart manage to involve several players.

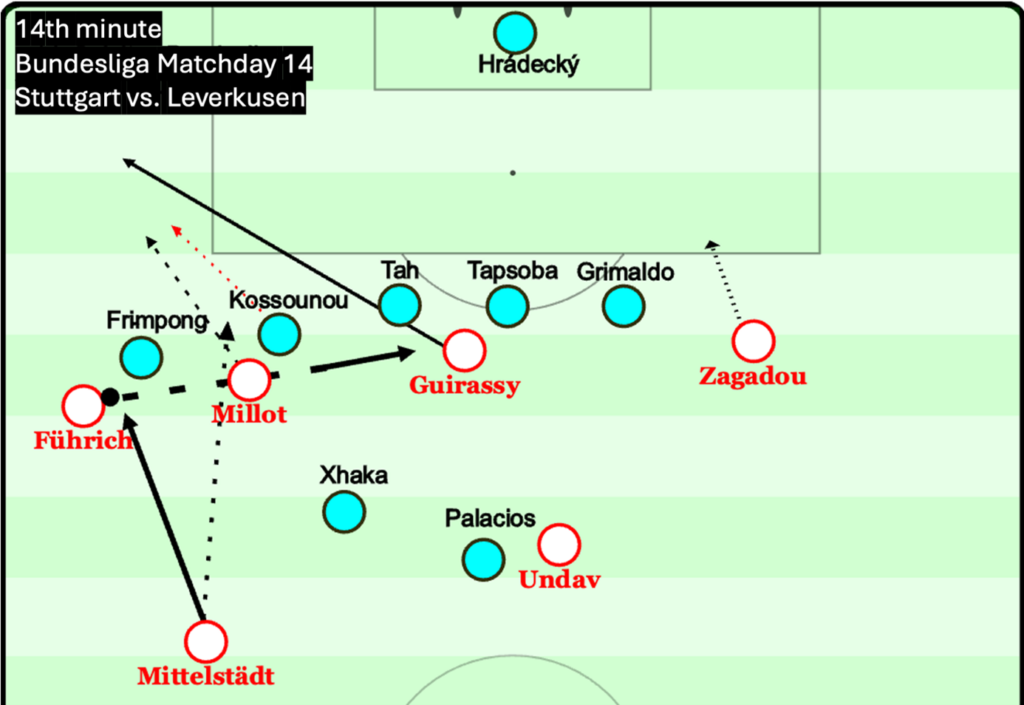

A good example is the 14th minute of the Bundesliga match against Leverkusen. Mittelstädt receives the ball and plays it to the wide-standing Führich, who dribbles diagonally towards Frimpong. Millot (actually in right midfield) has already overloaded the centre. When Mittelstädt passes to Führich, Millot runs into the open space.

With this run, he pulls Kossounou with him and opens up the space for Mittelstädt. He runs at full speed into the free space. As a result, Führich has two passing options (one to his left and one to his right). Due to the different running routes of Millot and Mittelstädt, two players, Xhaka and Kossounou, are pulled out, briefly creating more space in the centre. Führich decides to move into the centre and plays to Guirassy. Frimpong, Xhaka and Kossounou push back into the centre, leaving Millot completely free on the wing. He is able to cross without any pressure from his opponent.The scene is intended to show how a high level of activity by as many players as possible at the same time and many simultaneous runs can open up space for the opponent.

The box occupation on Millot’s subsequent cross illustrates how active Stuttgart are and how determined they are to “get the ball”. In addition to Führich and Guirassy, two other players, Vagnoman and Undav, occupied the box. Vagnoman (actually a right-back) joined the attack at full speed and could therefore be found at the 2nd post when the ball was played in. The same applies to Undav, who also comes forwards at full speed in order to be in the box in time.

A harmonious, unequal striker duo

The two strikers Dennis Undav and Serhou Guirassy are the statistically most noticeable factor. Despite Undav’s injury at the start of the season and Guirassy’s injury and participation in the Africa Cup during the season, the striker duo have 55 direct participations in goals after 31 match days.

Guirassy scored 25 goals and 3 assists after 25 games. Undav has 18 goals and 9 assists after 27 games. The two strikers complement each other very well, which could be due to the fact that both interpret and fulfil the central striker position very differently. Undav is very variable in terms of his position. In his own ball possession, he always drops down. When attacks are launched from the outside, he also moves to the side and thereby serves as an additional passing option. Guirassy tends to stay in a central position at the height of the last line and waits for spaces to open up and for passes behind the opposing defence.

Undav constantly confronts the opposing defenders with the decision of whether to go with him or not. If they do, this creates a large gap that can be exploited by Guirassy, Stuttgart’s outside midfielders or the 6s.

It’s no longer a secret that Guirassy only needs a little space to become very dangerous with his speed and intelligence.

If the centre-back doesn’t go with him, Undav’s clever positioning and forward orientation allow him to look for spaces in which he can turn up and create dangerous situations.

If the opponent covers Undav with a defensive midfielder, a lot of space is created in the central midfield, as Undav is constantly on the move and pulls his opponent out of the central position when man-marking in order to open up the dangerous spaces in the centre for his teammates.

When Undav was still injured at the start of the season, Stuttgart played with Guirassy as their only striker. Guirassy often dropped back to pull the centre-backs out of their positions. This still happens at times. As Stuttgart want to have a deep passing option at all times, Undav is positioned in the centre of the last line and swaps roles with Guirassy.

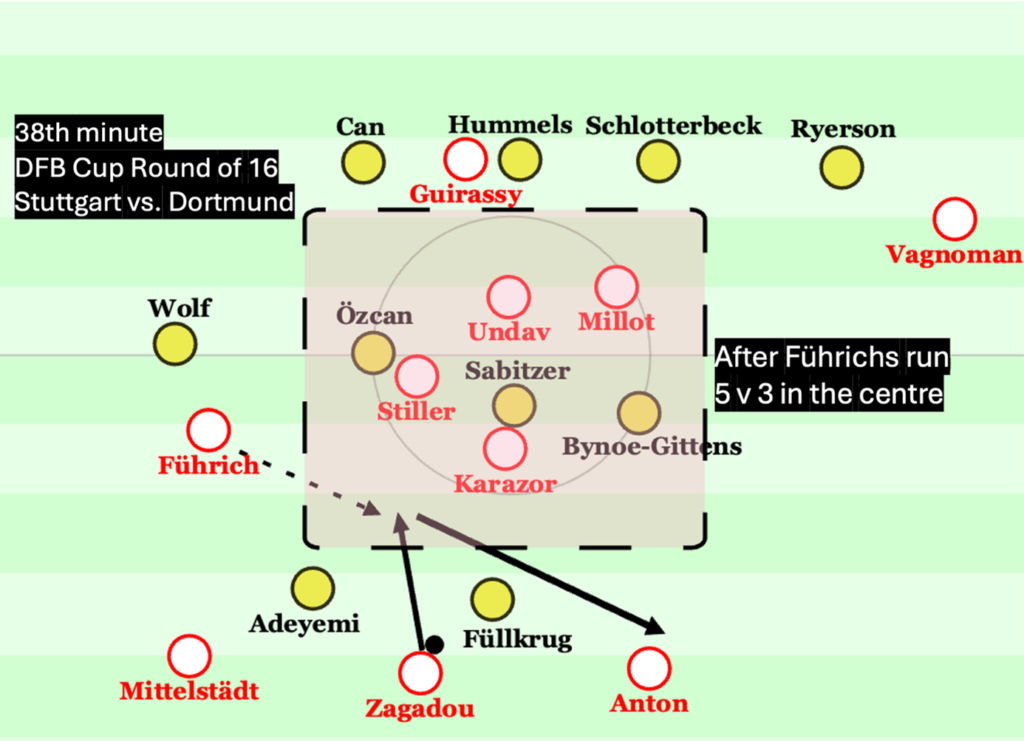

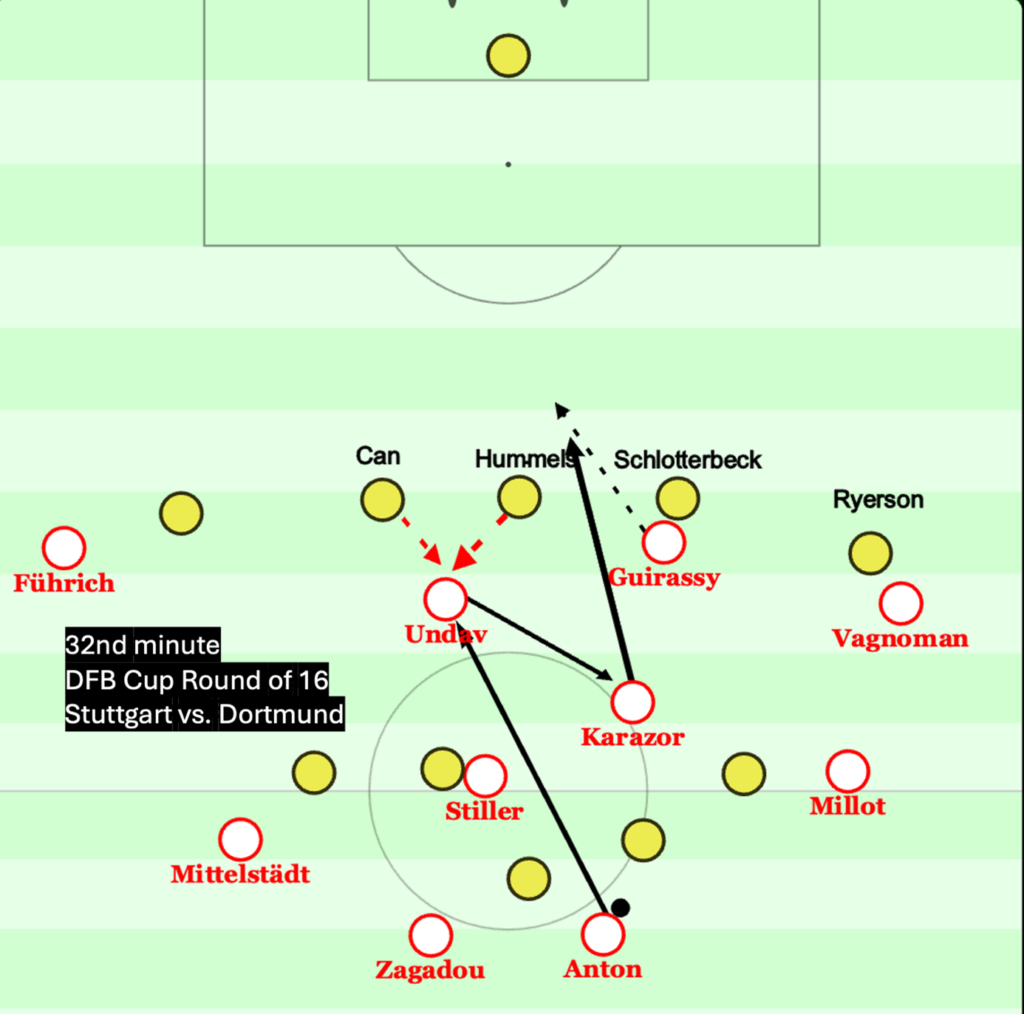

In the DFB Cup round of 16 (2:0 for Stuttgart), Dortmund deployed three centre-backs against Undav and Guirassy in order to close down the spaces described above (when Undav or Guirassy drop off). Dortmund defended on the last line in 3v2, with the outside centre-back close to the ball consistently following the path of Undav or Guirassy (depending on who is dropping off). The central centre-back Hummels should close the gap created by his centre-back colleague with the other outside centre-back. Dortmund’s two full-backs were tied down by Stuttgart’s very wide outside midfielders. As a result, the paths back into the centre were also very wide.

Shortly before the scene in the picture, Undav is still occupying the deep area, while Guirassy drops into the half-space. Only Schlotterbeck (the outside centre-back) goes with Guirassy. As a result, the centre is still closed by Hummels and Can. As soon as Undav also tilts, Guirassy pushes up again (as shown in the picture). This time, however, Undav deliberately positioned himself between Hummels and Can as he tipped over. As a result, both feel responsible for Undav, causing both to push forwards impulsively.

Undav allows the ball to bounce onto Karazor, who is ready to make contact. This play across the third allows Guirassy to be played on directly by Karazor (also with the first contact). Unfortunately, the pass was not perfect and the ball was intercepted. However, Guirassy launched himself into the space behind Hummels at exactly the right moment, so that he would not have been offside.

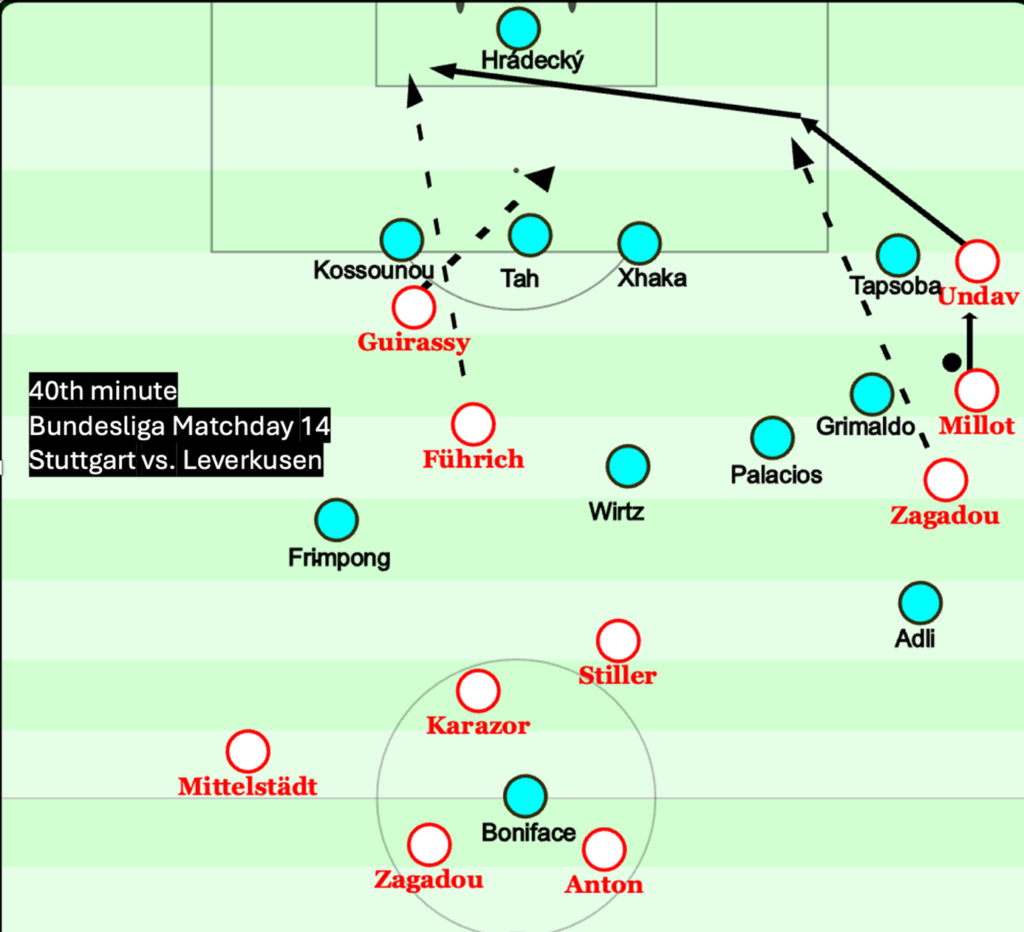

In addition to Undav’s vertical dropping, the horizontal dropping was also discussed at the beginning of the section. A very good example of this is how the 1:0 against Bayer Leverkusen in the Bundesliga first leg of both teams came about.

Leverkusen lose the ball on the halfway line, which means that the two full-backs Frimpong and Grimaldo have moved up and Xhaka takes over the centre-back position of the withdrawn Tapsoba. However, Tapsoba is only pulled out because Undav drops to the left side when Stuttgart win the ball. Guirassy, on the other hand, once again occupies the centre position and waits for a deep pass. Leverkusen even defend very well at first, as Xhaka fills Tapsoba’s position. After Undav plays the pass deep to Zagadou, Guirassy runs towards the 11m spot.

With all the defenders looking towards the ball or Guirassy, the space at the second post opens up for Führich, who scores to make it 1:0. Although Undav and Guirassy had no direct involvement in the goal, both were crucial to the goal.

Conclusion

Hoeneß has managed to make Stuttgart more unpredictable for their opponents with many tactical tricks, such as changing positions in the build-up play and overloading certain zones. At the same time, Stuttgart remain true to their line and consistently try to use playful solutions to gain space and find free players. With clever positional play, Stuttgart use their full-backs in the half-space to protect against the high risk of flat build-up play and consequently minimise the risk of running openly into counter-attacks.

Another factor is the composition of the squad with players like Guirassy and Undav, who complement each other perfectly. It is also an advantage that Stuttgart have several players in their squad who have been educated in different positions. Millot, for example, can play as an outside midfielder as well as a 6 or 10 and therefore fits perfectly into Hoeneß’ system and position changes. In a very short space of time, he has managed to utilise the possibilities of the Stuttgart squad almost to the maximum. It remains to be seen how Stuttgart will perform in the coming season with a heavier workload and how they will play against top teams such as Real Madrid and others. But it is already clear that Hoeneß has developed VFB into a top German team in an astonishingly short space of time.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

CarlosGarcia09 June 26, 2024 um 3:04 pm

How do you prepare, as a coach, to play against this type of opponent? It is verty difficult, because the mobility they have gives them variability. Maybe the training will be focus on players interpretation…

And another question, whay software do you use for the images? They look nice.

thanks a lot