The Various Forms of Restdefences Part 2: Counterattacking

In part one we dissected the various forms you can use to build your restdefence. In this second part we look at the different counterattacking methods coaches can adopt against the different types of restdefences. We are looking at the different counterattacking strategies and what restdefence shapes they’re most effective against.

Unlayering

The first counterattacking strategy is unlayering. Unlayering is when you try to destablise the organisation of the restdefence by pulling them into inferior positions to prevent them covering one another. This comes to fruition more when the opposition’s restdefence are man-marking the restoffence because the defenders adapt themselves to the position of the attackers.

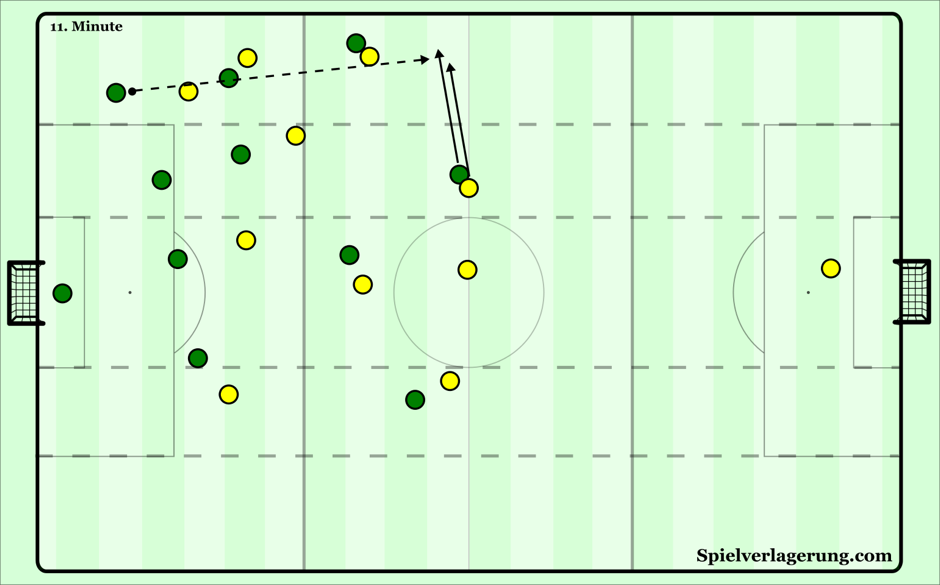

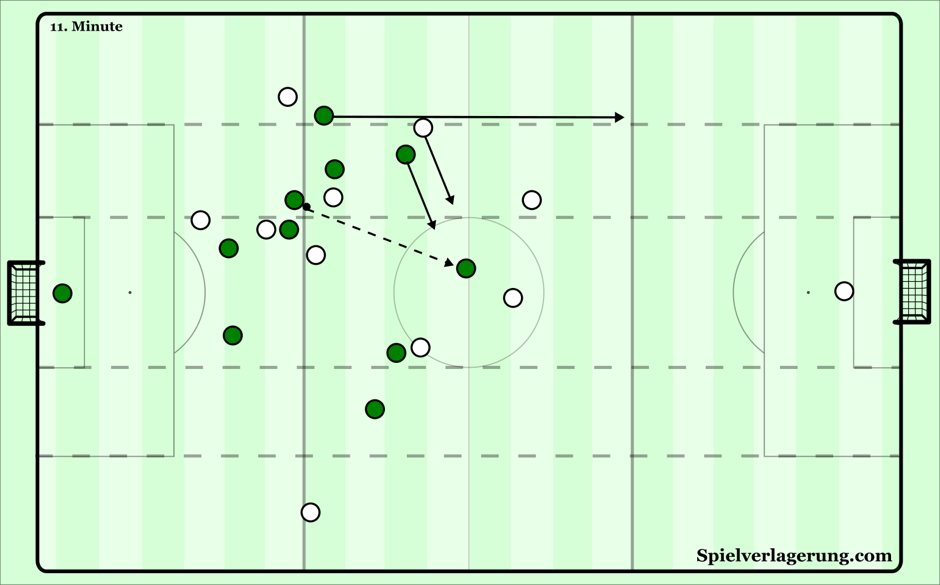

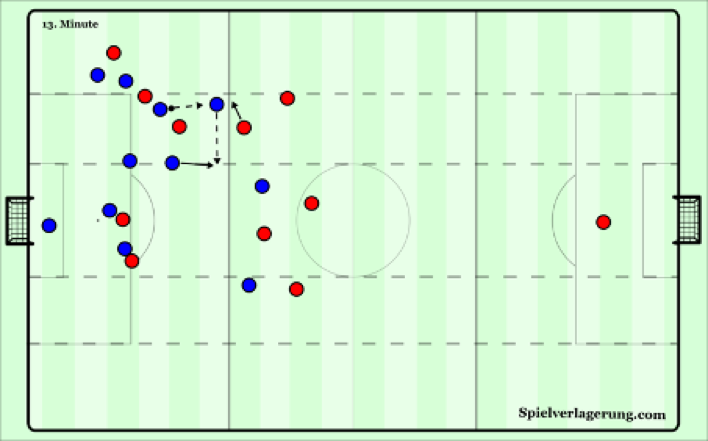

The first element to unlayering is usually to retain the wide players in high positions, near the halfway line. This ensures that the players on the side of the restdefence are unable to receive cover from the player in the centre, who would now have to drop into their own half to provide cover, which would disrupt the teams compaction. In addition, it increases both the space within the restdefence structure, as well as the space between the restdefence structure and the rest of the team as the distances between lines now become a lot bigger.A practical example of unlayering a 1-2-1 restdefence shape, for example, is to first move the wingers higher up, to move the restdefence players on the outside further back. Secondly, dismark the player at the top of the diamond, who’s tasked with marking the third attacker. This can be done in two ways. The striker can drop all the way back which pulls the defender with him, increasing the space between the player at the top of the diamond and the other three players. In this scenario, there is a lack of secondary pressing support from other players in the restdefence as the side players are pinned-back by the other two attackers.

The second option to dismark the player at the top of the diamond is by moving the striker into a higher position, flattening out the structure and creating a big open space in midfield. This seems to be less beneficial for creating direct counterattacks, as the defenders retain a 4v3 in the last line. However, it can be beneficial for retaining possession, as the player who is in the most ideal position to apply direct counterpressing is forced back. This in turn can create more space for the midfielders to play out of any initial pressure and advance forwards.

Exploiting Wide Areas

When looking at the restdefence shapes we have discussed, they all have a common theme of prioritising and focussing on the centre of the pitch because this offers the quickest route to goal for the opposition.

In addition, most teams will use a maximum of three vertical lanes to progress their counterattack. This can either be halfspace-centre-halfspace or wing-halfspace-centre. The reasoning behind this is because the more channels you use, the more players become isolated as the distances become too big, which slows down the counterattacks and allows the opposition to collapse into organisation.

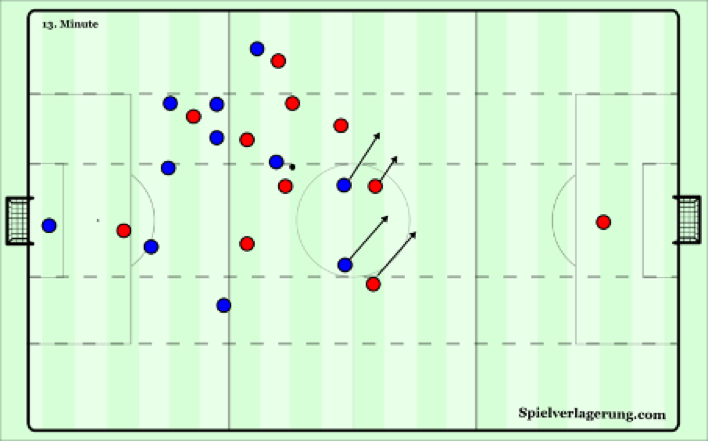

The main weakness of restdefences who set up with a maximum of three players in the first line is the space on the sides of the central defenders and pivot, because their position is emptying the space on the flanks. With just three players or less, it’s nearly impossible for the central defenders to cover the entire width of the pitch by themselves. Therefore teams countering these areas could find success. Depending on the habits of the counterattacking team, they can access these wide areas in different ways. First of all, it can be done with a direct run into the open space. Once the team steps into counterpressing assignments, the opposing team can use lofted direct passes into this space for onrushing teammates to bypass any immediate pressure and exploit the flanked areas. This player can also be a goalkeeper who just catches the ball and now plays a direct long ball into the open space. A direct run in behind works best when it is made on the opposite side of the field, as this utilises the defender’s blindside and uses the movement of the defenders against them.

A secondary option could be finding the free man to dribble up field and attack the said spaces afforded by the restdefences starting positions. For example against a compact restdefence shape, if the counterattacking team can find the free man in deeper areas they can attack these spaces directly through dribbling movements. This then forces players in the restdefence to engage with them with outward pressing, which creates spaces and better opportunities in the more central areas of the pitch.

A third way is to have the striker move into the open space on the wing. The main benefit of this is that it usually pulls a central defender with him to the side, opening up spaces in the centre. In addition, especially when you have a big, strong striker who’s able to shield the ball, it can be an option when the opponents are able to get some pressure onto you and the counterattack has to be started with a long ball.

The final option to exploit the open space on the sides is by using 3rd man run movements. A 3rd man run is where player A passes to player B, whilst player C makes the movement to break lines and receive the next pass.

Especially when the player on the side in the line of three is pulled inwards by another player, a player making a run into the space on the side might go unnoticed. Or the player will be noticed, but the opposition doesn’t have a defender able to track his run. Generally the 3rd man run is very difficult to defend against, even in an organised structure, because of the forward momentum and orientation the ball-receiver finds themselves in.

Another option could perhaps also be to position your restoffense in very wide positions in the first place. As the defenders aren’t able to closely mark in those areas during the attacking stage you are able to receive. Belgium used this against Brazil in the 2018 World Cup. By having Lukaku and Hazard near the sideline in the restoffense. On one hand this makes these players harder to reach for the countering team, but on the other hand they are also very difficult to pick up for the opposition.

Blindside and rotational/dropping movements

Nominally, the striker stays as high as possible in restoffence occupying the central defenders, pinning their position and preventing them pressing forwards. Upon winning the ball, just as one of the midfielders can move into the space between the lines of the restdefence, the striker can decide to drop and make himself available creating a clear passing line. This then poses questions to the defenders, does one get enticed forward and follow these dropping movements, which destroys their compaction or do they stay zonal by letting the striker receive, which in turn enables the striker to turn and continue the counterattack.

However, if one of the central defenders follows him (which is usually the option they go for), the central defenders are torn apart and the space in the last line is even bigger. As there is now just one central defender left to cover the entire width of the pitch. This is an ideal situation to have another player make diagonal runs in behind to exploit the space on the sides.

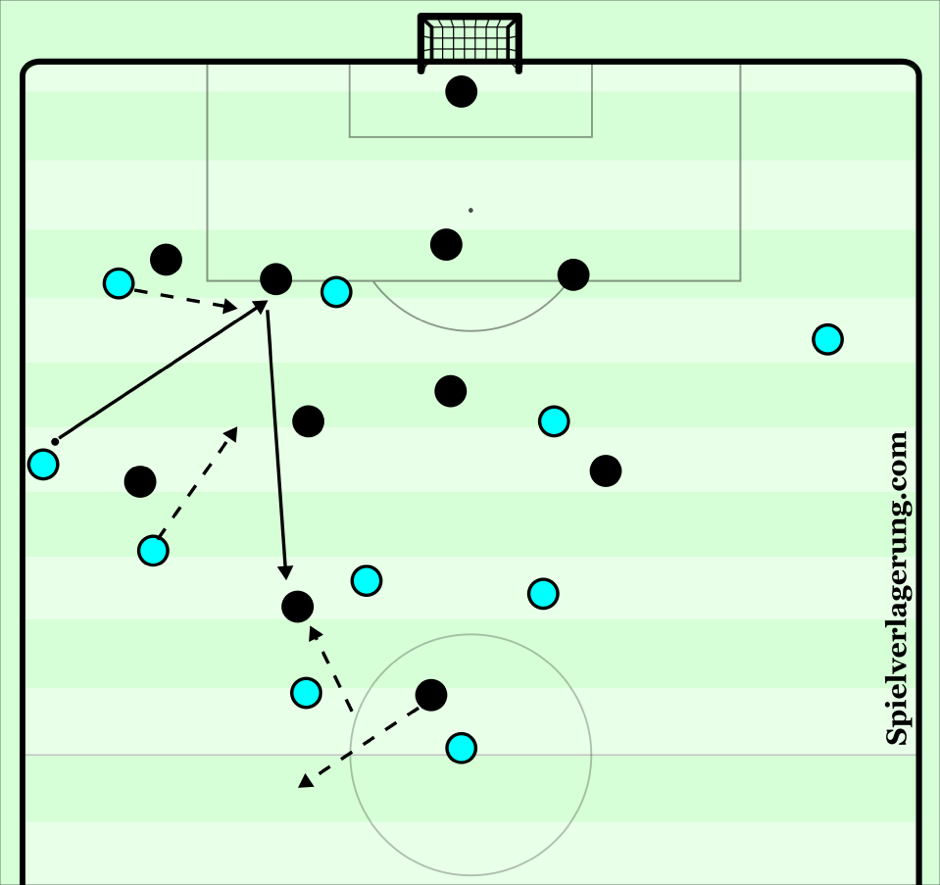

A lot of the counterattacks against restdefence structures with two on the first line start with a dropping movement of the striker. After this player receives to feet, this is the trigger for another player to aggressively move to receive the lay-off after which the runners can receive in behind.

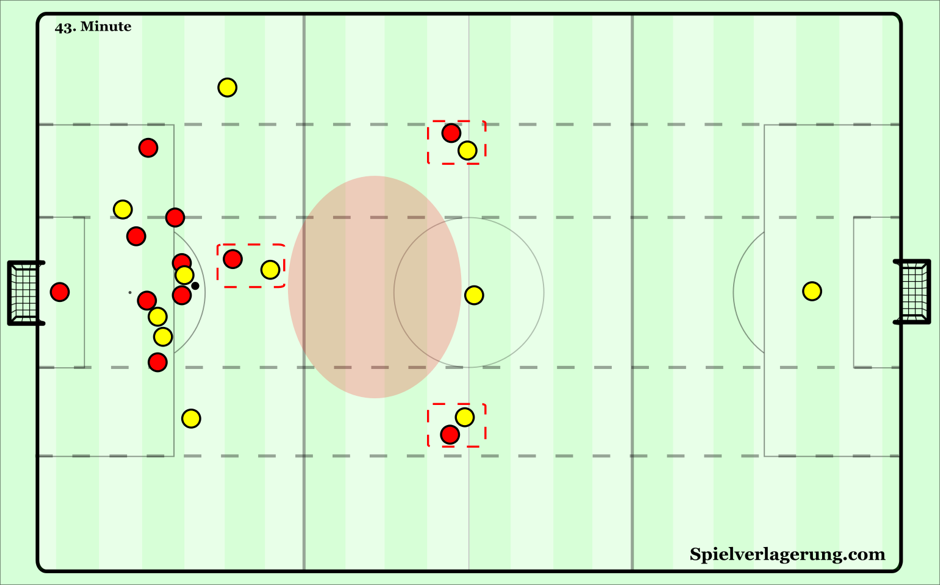

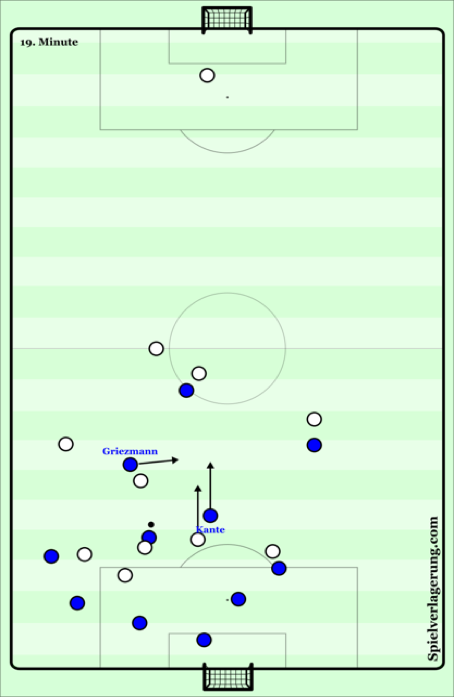

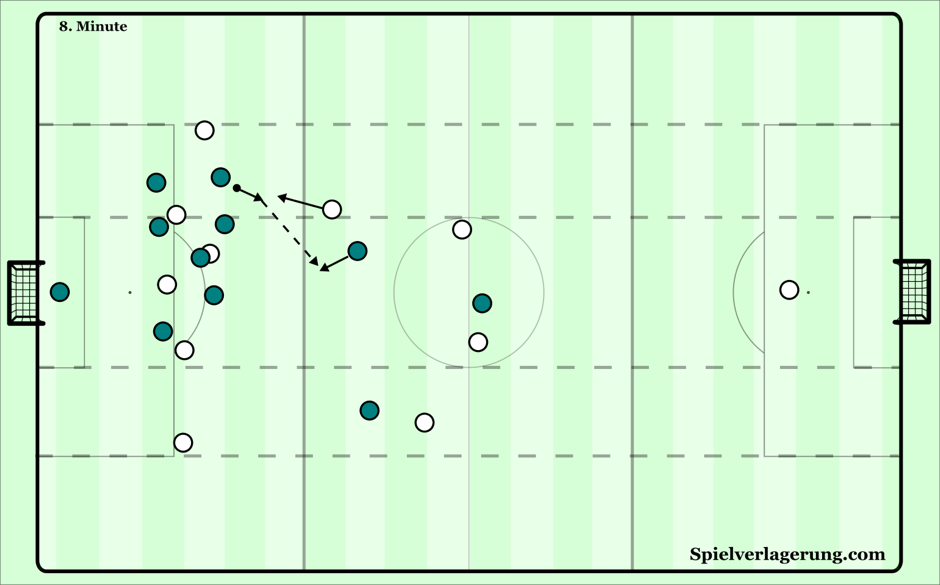

Let’s look at a practical example against a more zonal 2-2 restdefence. To help counterattack quicker, the opposition may leave a forward or two higher up in restoffence creating a 4v2 or 4v3. If the initial counterpressing actions are not successful due to the natural underload higher up (depending on how many players are in restoffence), the opposition may be afforded space and time to bypass the defensive midfielder with a vertical pass into the feet of the opposing striker. Initially the DM’s position is blocking the passing lane vertically, however the striker can drop from their position and receive on the DM’s blindside. This action may entice the ball-sided centreback to step up and apply heavy pressure against the ball. As one of the centrebacks has now been attracted forwards, the compactness has temporarily been weakened as it opens up even more spaces for the attacker to potentially exploit and advance towards the goal.

These spaces can be opened up when the opposition react to these blindside movements and apply counterpressing but are unsuccessful in winning the ball back, allowing the opposition’s midfielders to get into the space behind them or simply lay off to nearby teammates with better view of the field.

Wall Passes

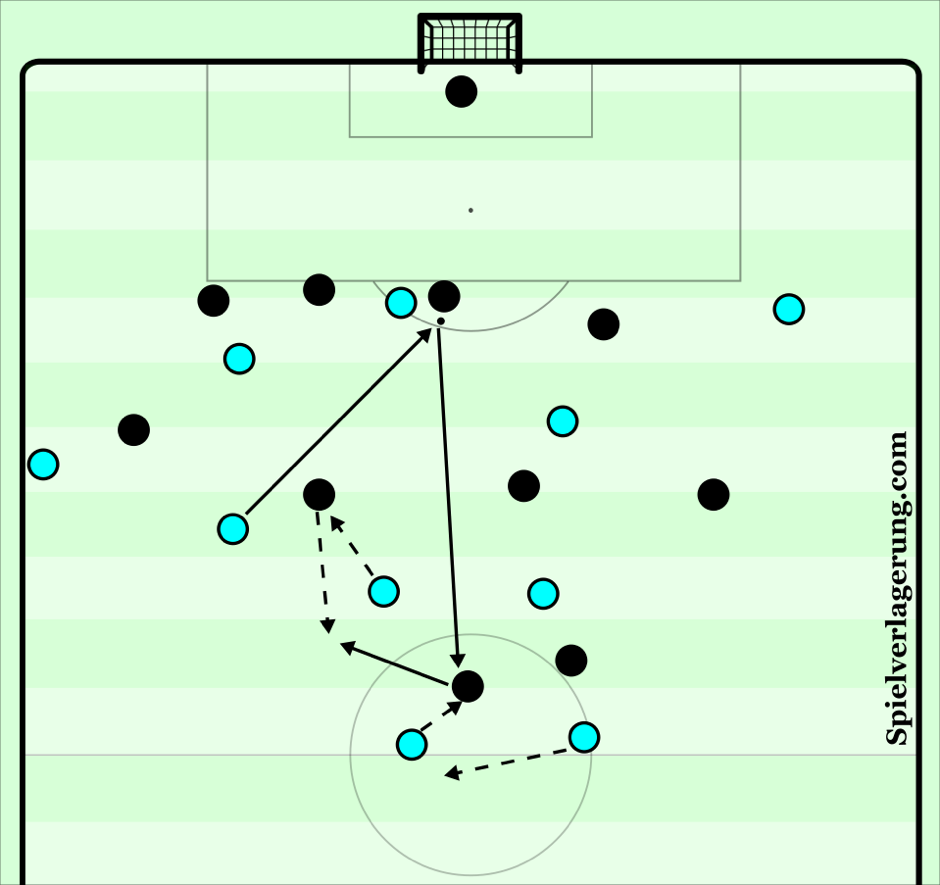

A common theme a lot of teams use in counterattacks are wall passes. This is basically a pass to the furthest player forward, who ‘bounces‘ it off in usually one touch to an onrushing player. The benefits of this are the ball receiver of the wall pass will be receiving the ball in a forward body orientation with a strong field of view, whilst already travelling at speed as they take their first few touches.

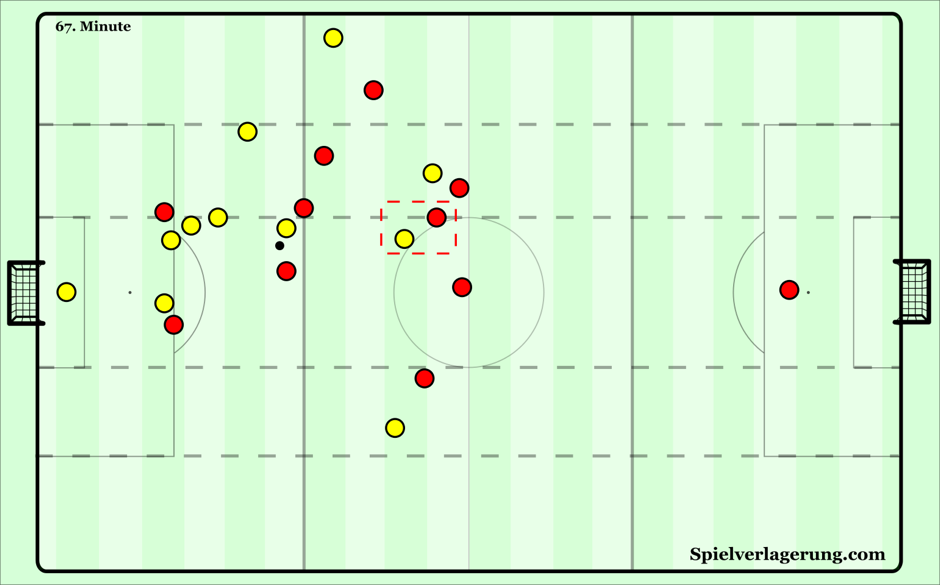

Here, If the pass into the opposing striker is made, the ball-near centreback will have to apply pressure in case the chance proposes itself to win the ball back through a poor touch or lay-off. If the lay-off is successful, the wall-pass receiver will normally be receiving on the blind side of the second line of restdefence due to the body orientation once the first pass is made. As the centreback has had to breach the first line, the defending side are now in an inferior position to cover the larger spaces with just one player tasked with covering the width of the field which in turn makes them vulnerable in the counterattack.

Creating Temporary Overloads

Creating overloads is easier when you have equal numbers in your restoffence as the opposing restdefence, so you can be matched up numerically and use effective dropping movements to create temporary overloads, which we have already highlighted. Similarly to the 1-2-1 shape which we have discussed, against a zonal 2-3 restdefence it can be beneficial to create a 2v1 overload against the central midfielder in order to create a free player to progress the counterattack. This 2v1 can be created in a number of ways: the striker can drop to overload the central midfielder, one of the players who was previously in the defensive shape can quickly join the attack to create the 2v1, or one of the players in the restoffence can position himself between the lines, allowing him to move out of the blindside of the central midfielder in order to receive the ball.

One of the main differences between the 3-2 shape and, for example, the 2-3 shape is the number of players positioned in the first line of the restdefence. Whereas the 2-3 shape has optimal access to press the initial ball-carrier, and less defensive coverage in behind, the 3-2 shape is the other way around. As there are just two players in the first line of the restdefence, the team has less coverage in the first line and thus inferior cover of these spaces.

When setting up a counterattack against the 3-2 shape, it can thus be effective to overload the line of two in order to create platforms to progress and set-up the counterattack. This can be done by having one of the players who was positioned in the defensive shape quickly join the attack in order to overload the midfield.

Dropping one of the strikers back in order to create this overload in the first line is also an option, but due to the set-up of the 3-2 shape, probably less effective. The dropping striker can be followed by one of the defenders from the second line, without the possibility of creating spaces to exploit for teammates as there is coverage at the back. In addition, it would create problems for the follow-up action. Let’s suppose the striker drops to overload the first line and none of the defenders follows him. The striker can turn, however as he has dropped there is only one player left who can make runs against the last line. As there are three defenders positioned there, the possibilities of creating danger are very slim.

Especially when deploying this option, the follow-up movement is usually to create a 2v1 against the player at the top of the diamond. This is usually done by having one of the midfielders immediately move forwards into the open space on the blindside of the opposing player. Together with the player in the centre this creates considerable platforms to create a 2v1 together to progress the counterattack quickly. Once a free player is created the team can advance forwards.

Diagonal Runs

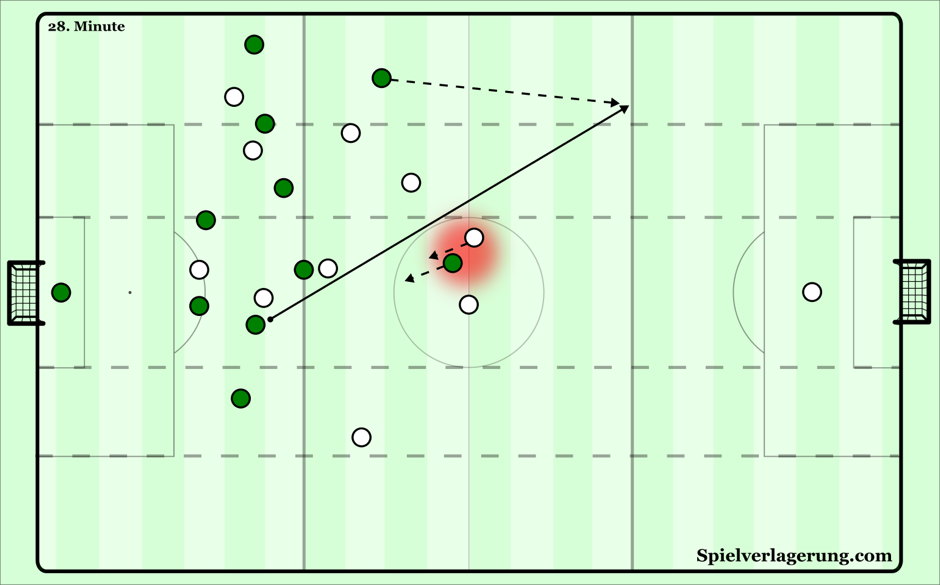

Against more zonal restdefences, such as the 3-2 or 2-3 restdefence shape, beating the first line can be rather difficult, as with three players the width of the pitch can be defended well enough and the attackers are usually in an underloaded situation. The runs of the attackers will therefore be aimed at trying to pin the defenders and creating a 1v1 situation. Most importantly to achieve this is to dismark the middle centre back via a pinning movement, to ensure he can’t provide cover for the side centreback.

A good way to achieve this is by making diagonal runs once a player has time and space on the ball to play a pass in behind. By positioning one of the players from the restoffence near the middle centre back, a diagonal run will pull the defender out of position. Which opens up space for another attacker to make the diagonal run into the open space.

Positioning between the lines (Lines are too far apart)

Lastly, this counterattacking method is more successful against both zonal and man-orientated restdefences. Against more zonal restdefences, this type of situation usually occurs when the second line is trying to apply counterpressing and therefore moves forward, but doesn’t win the ball, allowing the opposition to get into the space behind them. Another option can be the second line being too flat, and therefore unlayered, which can result in a through ball with none of the players in the line of three being able to intercept it. While it also occurs that the line of restdefence isn’t yet organised fully.

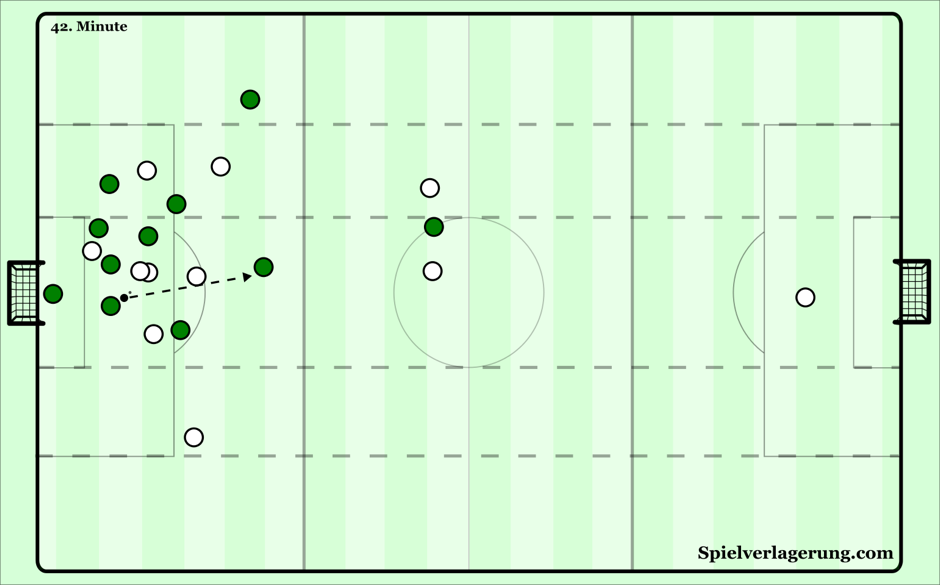

An example could be against a zonal restdefence which steps into counterpressing actions and are not successful. The first weakness in the 2-3restdefence structure, as manifested below, is that the structure can be exploited when the two lines are too far apart. When this is the case, a significant space opens up between these lines which can be exploited by the opposition. The opposing player that receives is able to turn with their back foot and immediately dribble at the two central defenders who play with a large space behind and to the side of them.

Against man-to-man restdefences, positioning yourself between the lines allows you to manipulate the restdefence of the opposition. By moving into spaces between the lines, the defender has to choose between either staying in position and allowing the restoffense attacker to get free, or to follow the movement, leaving space behind. By doing this, the restoffense attacker is able to either pull players from the first restdefence line forward and thereby opening spaces for runs in behind. Or the restoffense attacker can take up a higher position in order to force one of the restdefence players from the second line to take up lower position to disrupt the second line and generate more spaces between the first and second line. The reason for doing this is to reduce the opponents’ presence for counterpressing, in turn this allows the counter attack to be progressed quicker.

Written by Evert van Zoelen and Chris Baker

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen