Pressing traps available in a 3-4-3

Pressing systems involving a back three formation offer the opportunity to commit more players to press in higher areas. With seven players within the first and second lines of the press, there are opportunities for numerical advantages in specific moments within the opposition’s build-up.

If a team can use and adjust its man coverage system and structure to guide the opposition into favourable parts of their build-up, traps can be set, and then shut. This article will focus on some of the many variations of pressing traps which can be seen within a 3-4-3 structure, with its flexibility against a number of systems also highlighted.

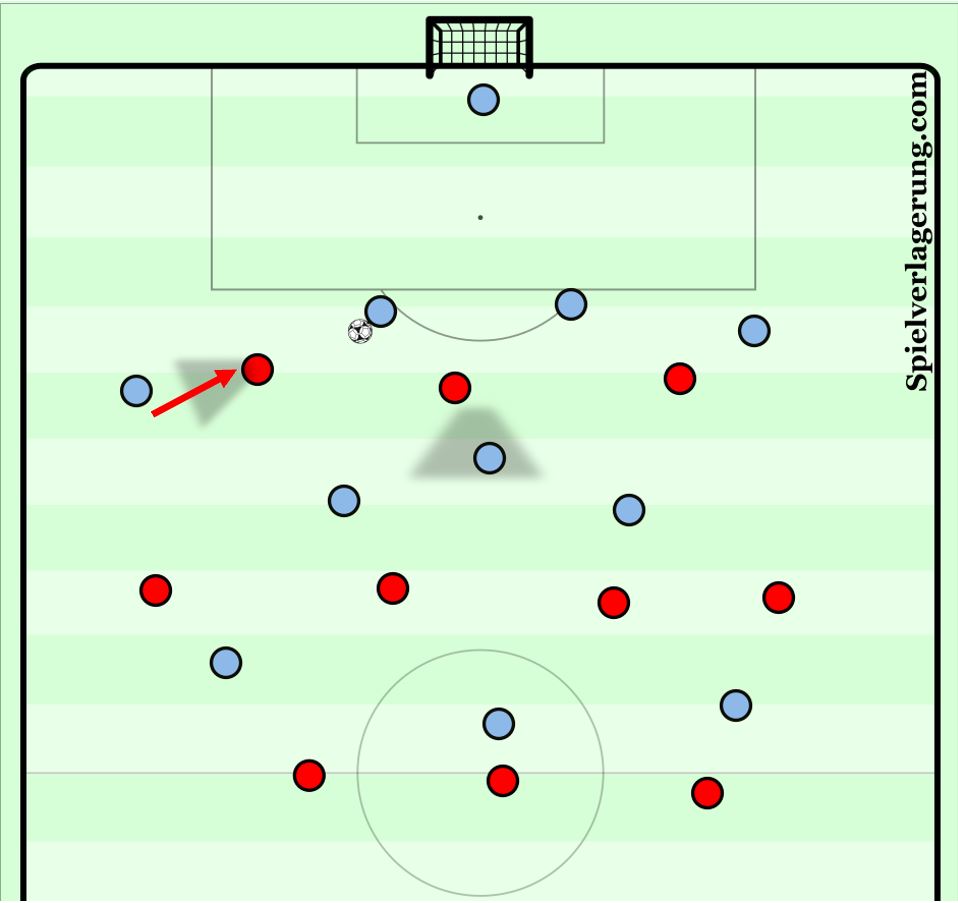

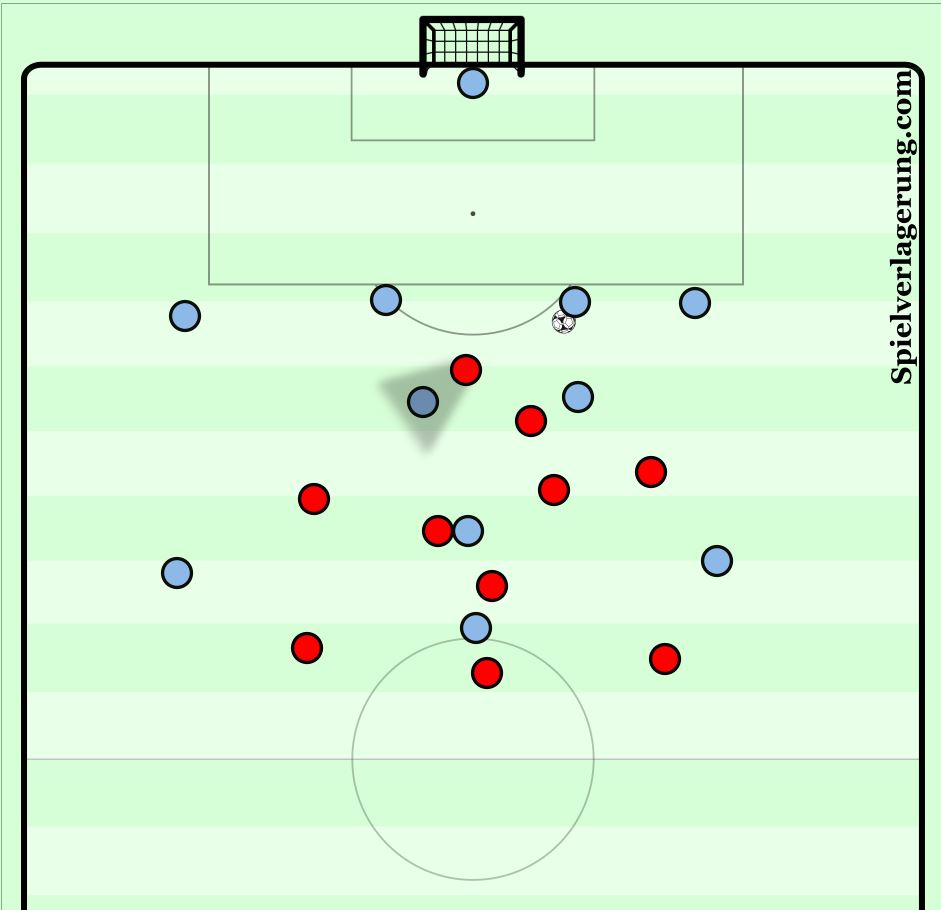

We can see below the basic parts of this pressing scheme within the 3-4-3 against a 4-3-3/4-5-1. The inside forwards press the centre-backs while keeping the full-backs within their cover shadows, while the striker keeps the pivot within their cover shadow, the same being seen in Jürgen Klopp’s Liverpool pressing scheme. The striker can jump from the pivot to the goalkeeper if needed while still keeping the pivot (six) within their cover shadow.

This pressing scheme therefore can in theory see three players press six opposition players within the first line, something which Pepijn Lijnders also mentioned with regards to Liverpool’s pressing.

This pressing scheme limits the oppositions’ ability to build in the wide areas, and therefore forces central build-up, which can then be used to set a number of pressing traps, such as the first most obvious one here.

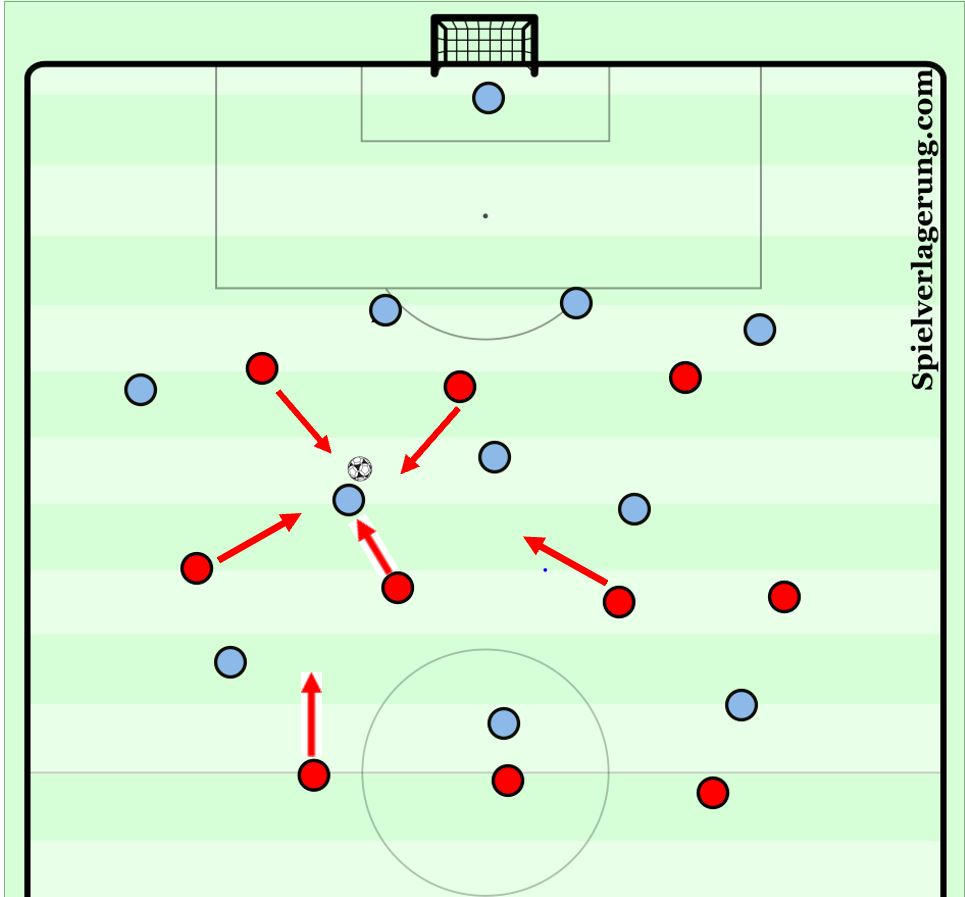

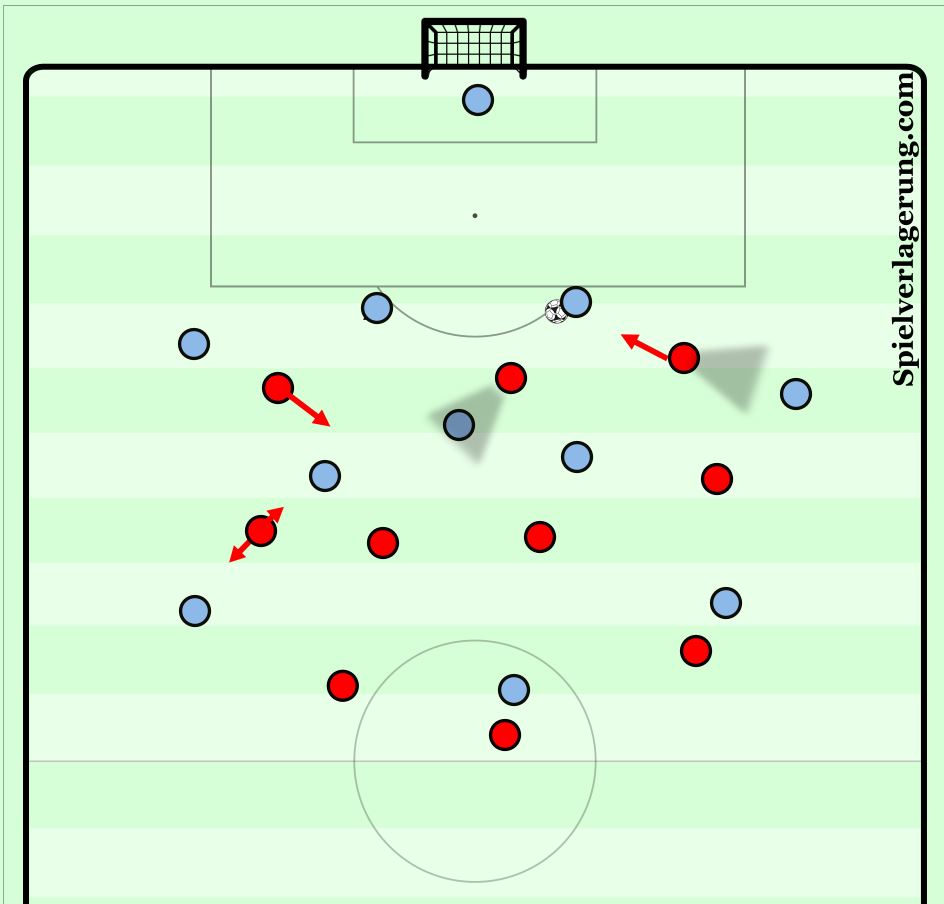

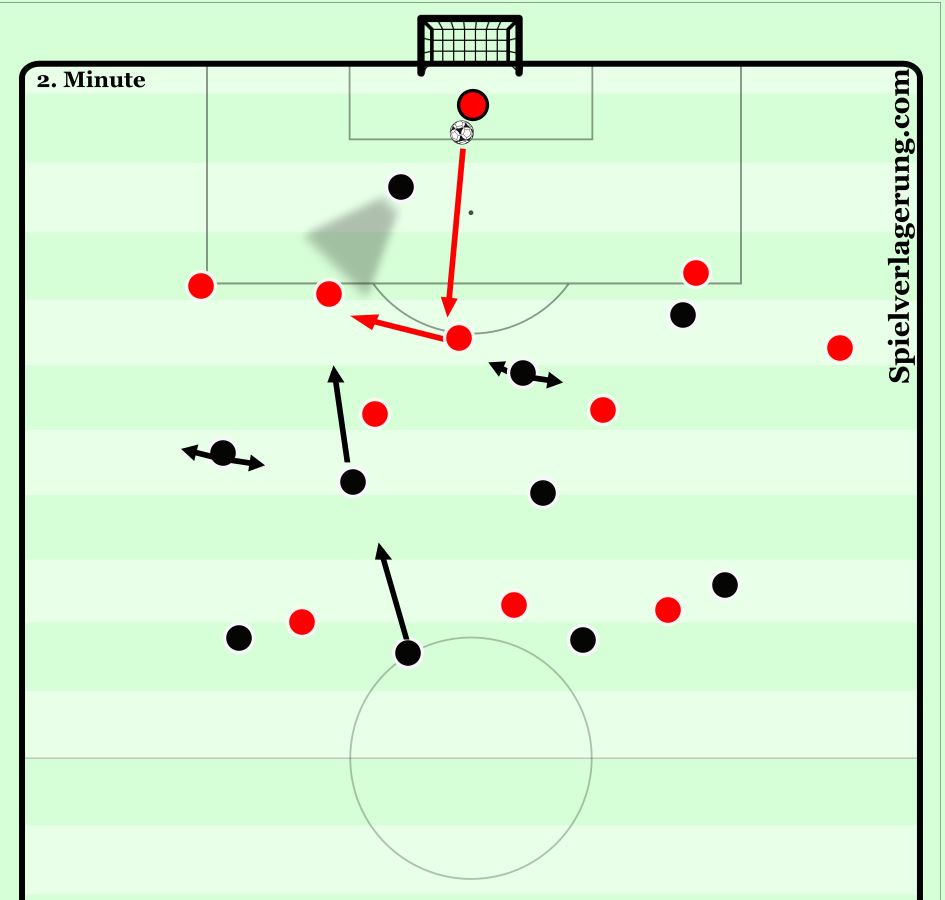

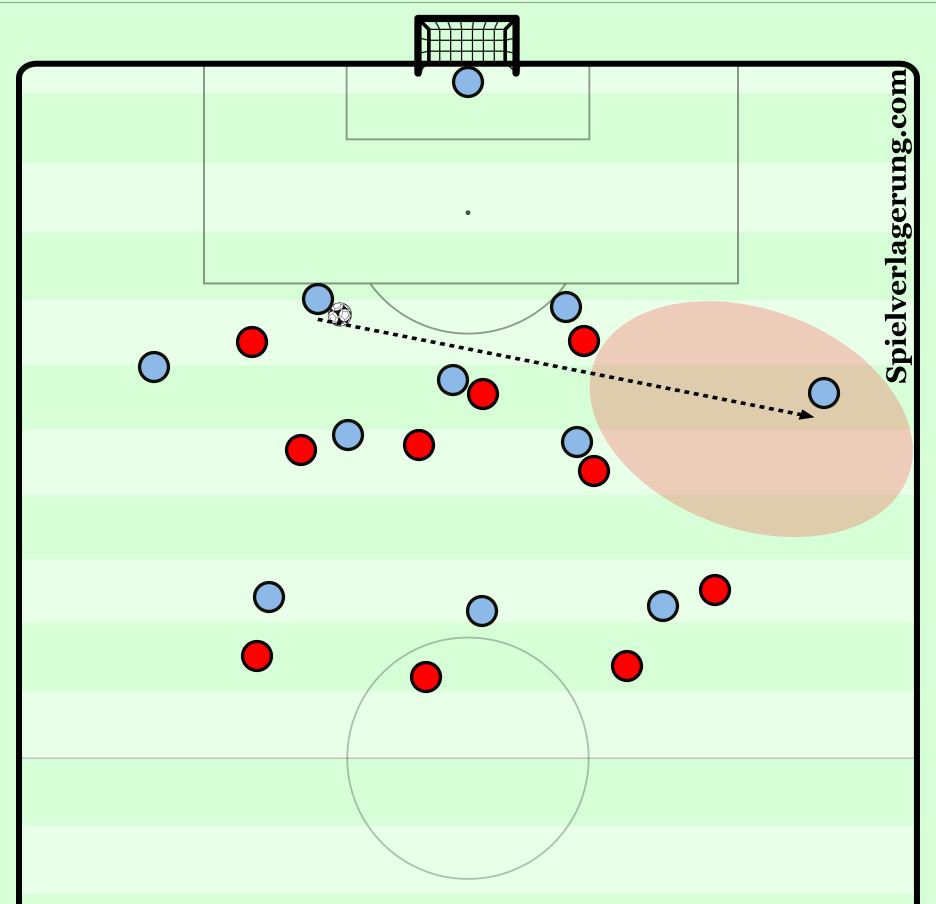

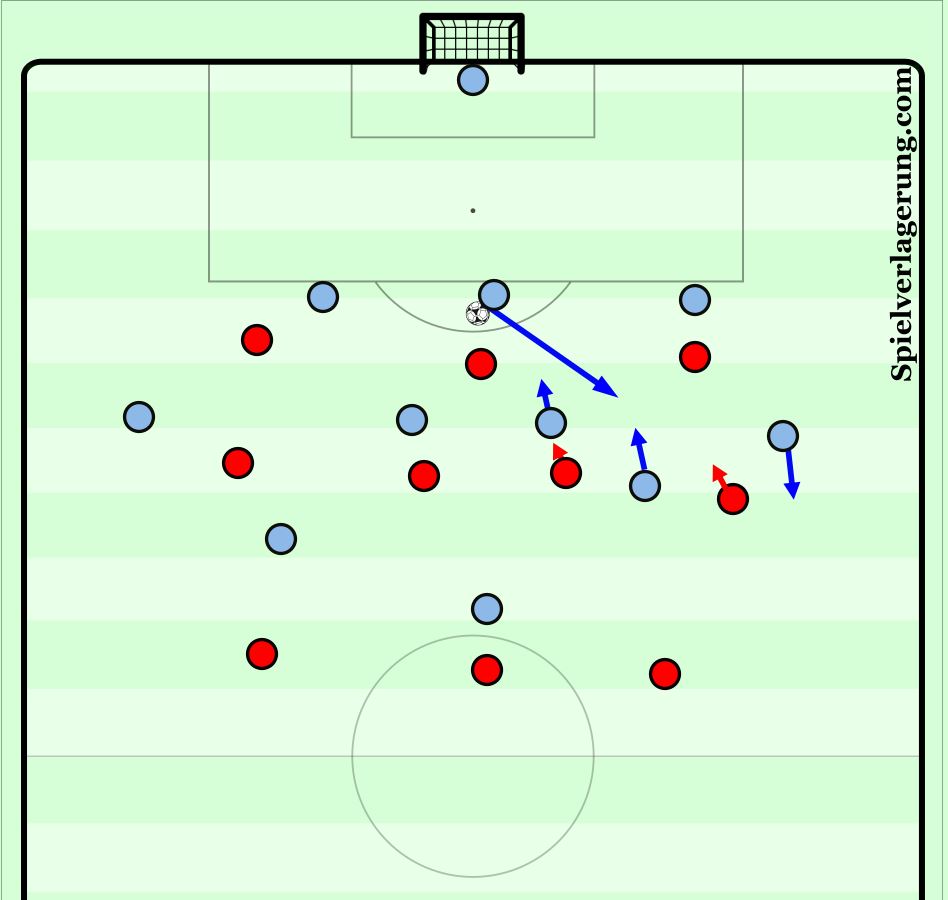

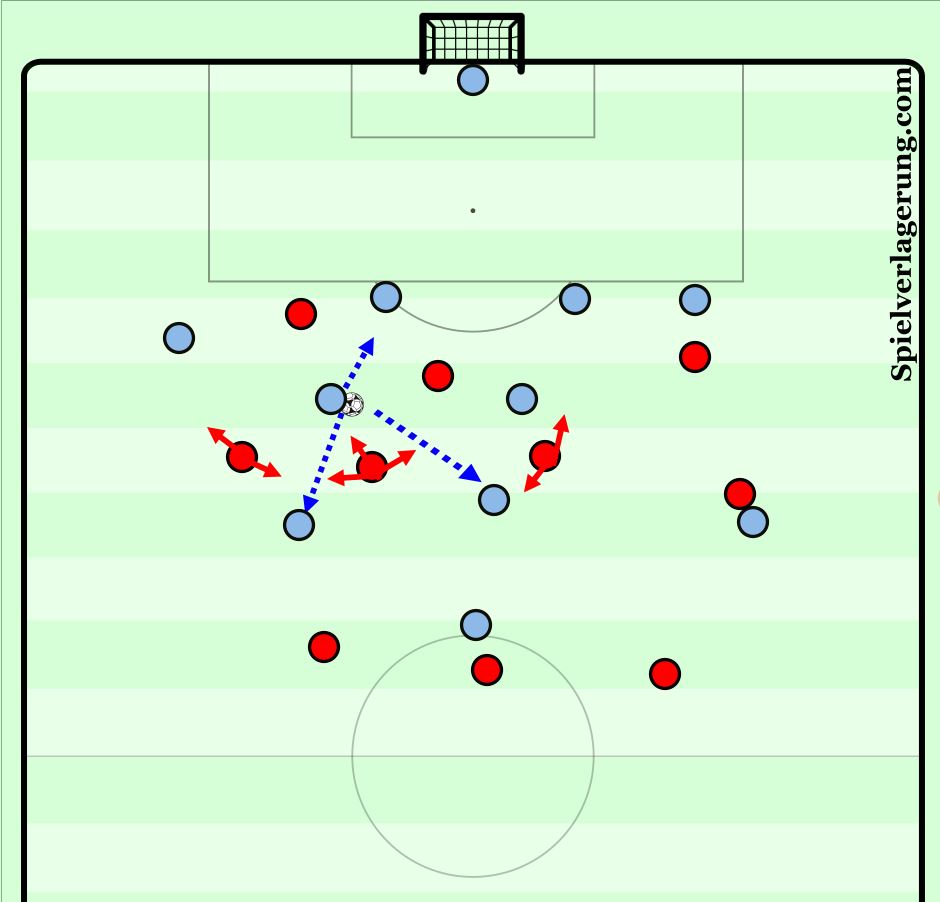

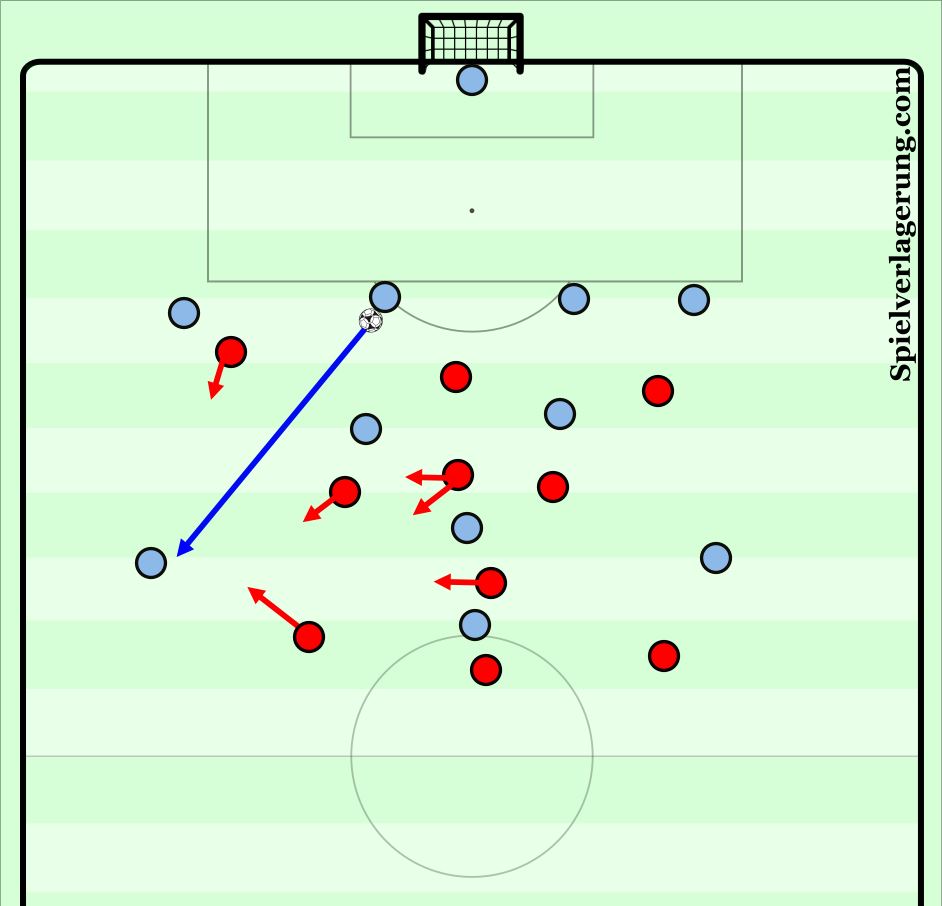

The passing lane between the pressing forward and central striker is deliberately left open to allow a pass to a central midfielder, who is left unmarked but within pressing distance of the central midfielder. This central midfielder then presses in tightly from behind, and the full-back can now push in and leave the winger in their cover shadow, and the winger can drop closer to the ball carrier while also occupying the lane to the full-back. The striker can also press closer to the ball carrier depending on the position of the six, and the ball far central midfielder (eight) can tuck in ball side of the opposition central midfielder.

This leaves the pressing side in this shape below around the ball, with five players available to immediately surround a player with poor body orientation. To prevent the receiving player attempting a pass backwards, on the cue of the pass being played the striker should move to cut the passing lane back to the centre-back, while also considering the positioning of the six, who can also be pressed by the nearby eight if the ball is played here. Adi Hütter’s Frankfurt used this pressing trap in both high and deeper areas, with the shape more of a 3-4-1-2 with a ten marking the pivot and marking Thiago from behind.

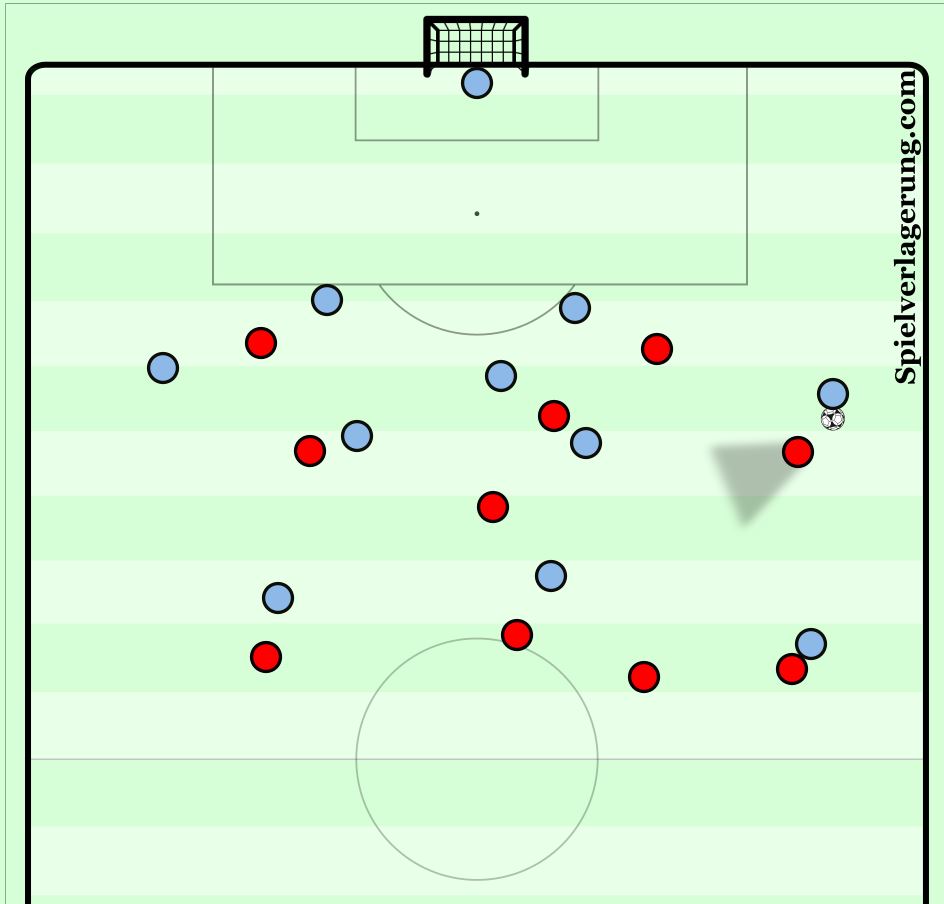

The only problem with the structure seen below now is if the opposition do manage a first time pass into the full-back, as the lack of height from the back line doesn’t allow for pressure. Therefore, if the ball does reach the full-back the defence should already be in this position below, with one of the centre-backs stepping higher and the rest of the defence covering across. From here the pressing winger/wing-back (number three) should press the ball carrier as tightly as is possible to prevent a potential switch of play and to prevent play down the line. Again, a short pass inside doesn’t pose a threat and instead plays into the same, now more compact, area, which may become so compact that the opposition choose not to play into it.

Therefore, if passive pressure is applied from this winger and the outside is protected, then the pressing trap becomes even more compact and probably too noticeable to the opponent, and so they are likely to look to switch the play. It is then the responsibility of the far side wingers to mark the opposition players, and the eight must also consider their positioning if the ball manages to go wide, which is an unlikely scenario.

If the opposition look to play very wide and expansive and push the far sided full-back on to creating a switching opportunity, the system can be adjusted again to prevent this and create another pressing trap.

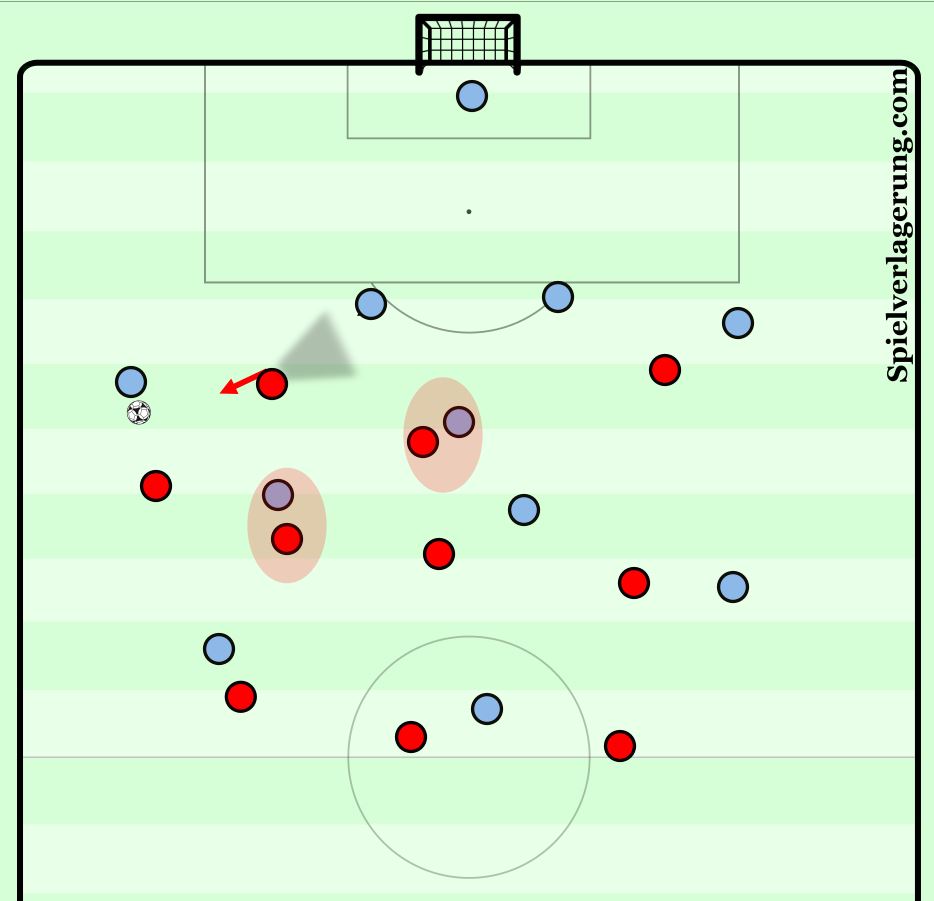

We can see the situation below, in which the far sided wide players push higher and wider in possession to stretch the pressing side. This makes the option of the inside forward pressing the centre-back more difficult, as it would require the winger/wing-back pushing onto the full-back in order to occupy the wide full-back in case of a long ball from the right centre-back. A centre-back also must push higher and across and the whole back line must shift also, which we can see below has occurred. Although this pushes a greater number of players into high areas, it does run the risk of a diagonal being played, with a 2v1 overload on the far sided winger causing potential decisional problems. The far sided inside forward must also tuck across to prevent a diagonal pass.

There is then again the option of making this a symmetrical shape and creating the same pressing trap on this side, but as mentioned the pressing distances increase after this switch and so this can become physically very demanding if constant switches are allowed.

With the potentially large pressing distances involved in this, there is instead another option that can be used. The shape can change to what now has become an asymmetrical 4-4-2 due to the right wing-back dropping into the defence. Now, instead of the inside forward pressing the centre-back, the striker can move from the pivot onto this player.

Because the striker is jumping from the pivot, they are pressing from the direction in which the pressing distances for teammates are largest, and this therefore gives time for the winger and central midfielders to get tighter in their positional marking. The pressing distances involved compared to the other example are smaller and therefore more efficient. There is also more cover for the vertical pass down the line, with a centre-back also available to cover the number two if they lose the duel.

A pressing trap could then be set around the eight or the six, with the six allowing for a better opportunity simply because it allows more time for the far inside forward to drop, and allows for direct pressure from the front by the central midfielder. The player in the right full-back position must remain extremely tight and man orientated to his player to prevent a pass being played, although in theory again because of the shape of the opposition there may be an opportunity for a wide pressing trap, which is something I’ll also cover.

We can see that pressing trap around the six here, after the lane was left open by the striker who cuts the lane back to the centre-back, meaning space was given for this six to receive the ball. From here the pressing side can form a compact shape covering forward and lateral options, and have enough players committed back so that if a penetrative pass is found they can deal with it effectively.

Traps from the goalkeeper

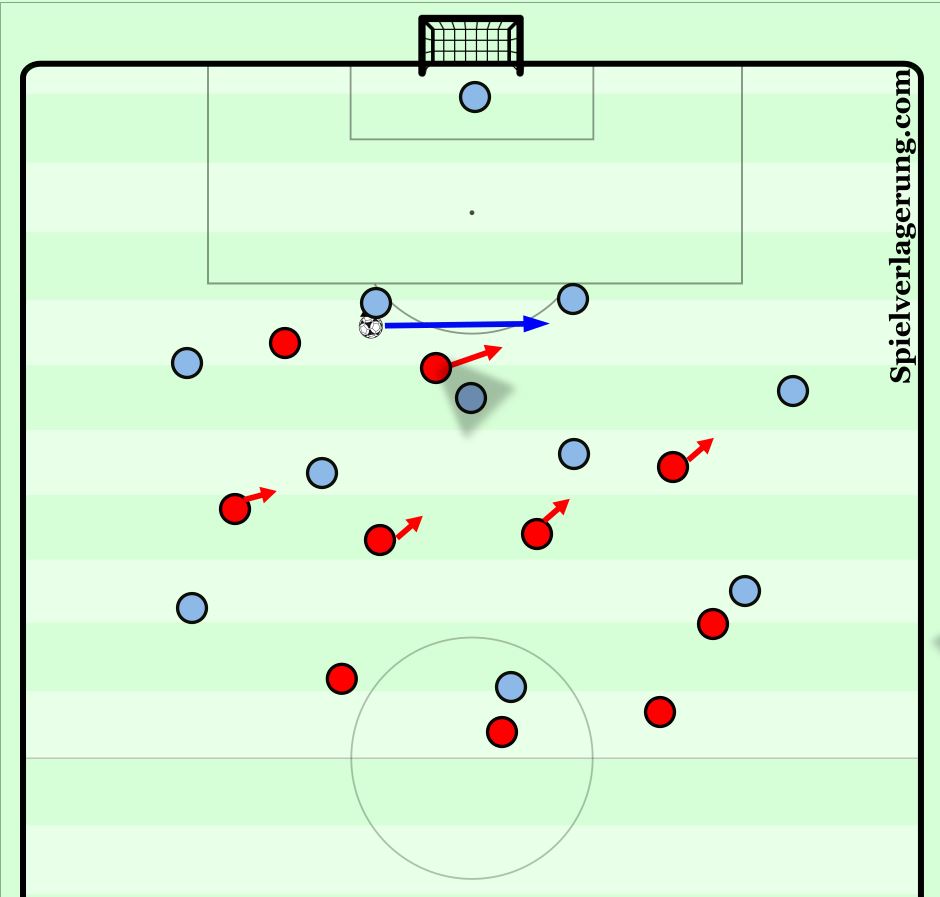

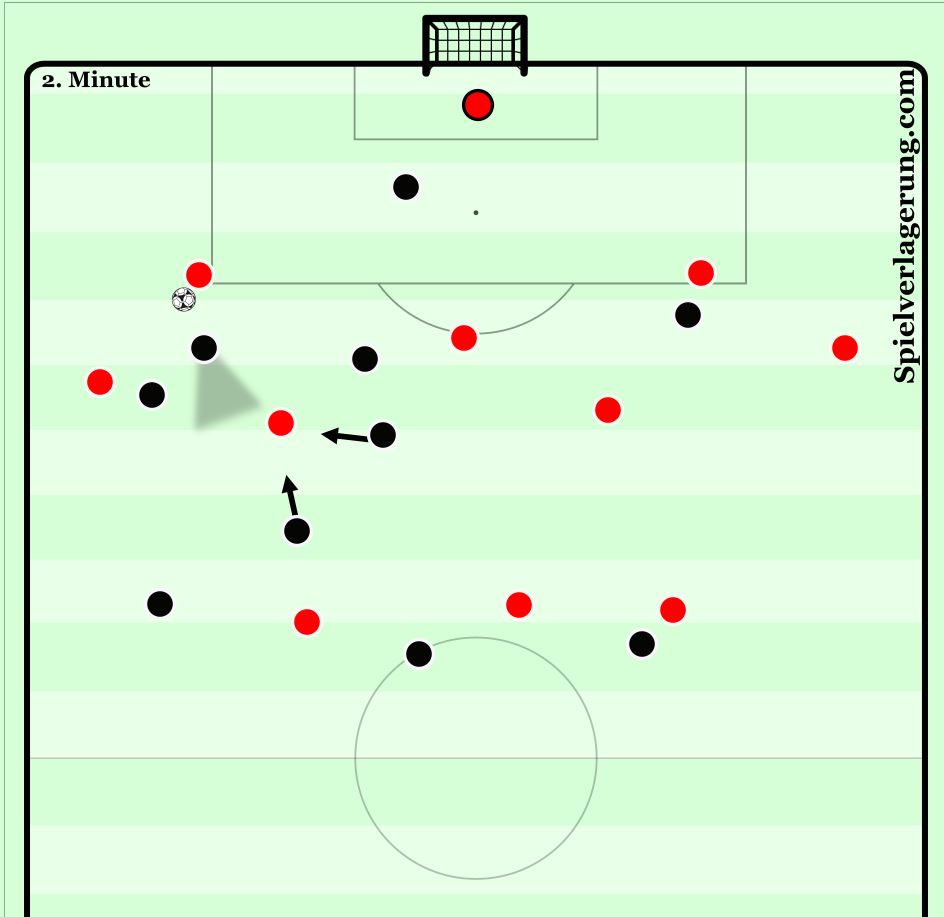

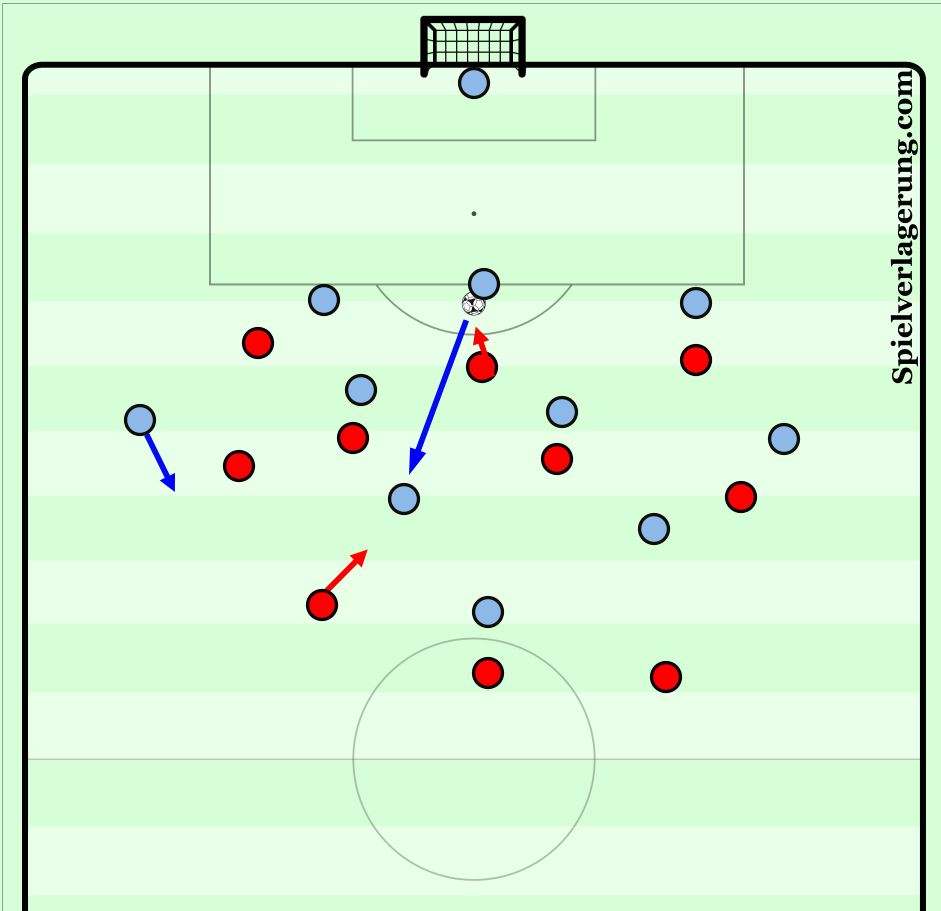

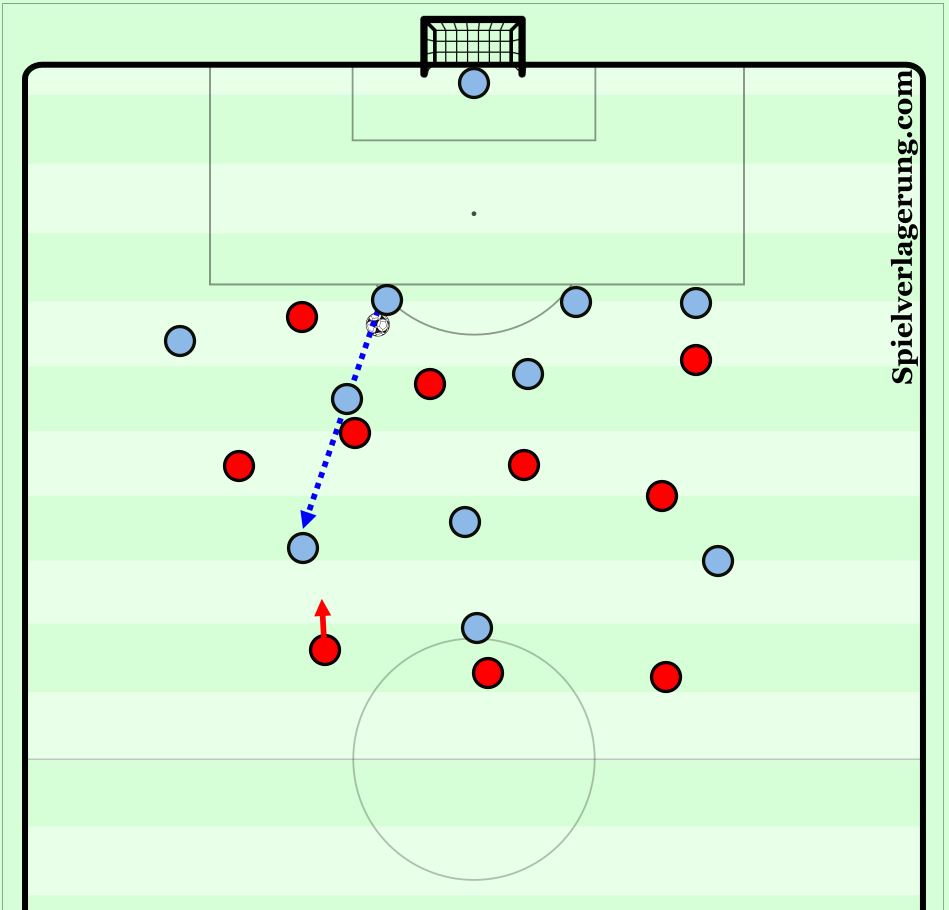

The following trap again is a variation on the 3-4-3 and has been used by Adi Hütter’s Eintracht Frankfurt, with this trap seen in a home match against Bayern in the 18/19 season. Bayern are pressed back to Manuel Neuer and the left sided striker presses inwards slowly towards the goalkeeper. The central striker (who here acts more like an attacking midfielder), stays behind the pivot but still applies pressure, favouring shielding the right side of the pitch in his decision making in order to set the trap and guide the pivot towards the opposition right centre-back. This pass to the centre-back triggers the central midfielder to jump to press.

With the trap set so that to get to the target player the opposition have to complete two passes, this allows for more time for this midfielder to cover the pressing distance, and can therefore get closer to the ball. The ball ends up in a wider area for the centre-back carrying the ball, and the Frankfurt midfielder simply cuts the passing lane and blocks the pass, leading to a throw. The left winger is also able to protect the inside lane, and we can see still though that if the ball gets past the first press with a difficult pass that the structure is still compact within this area, with a centre-back stepping higher to cover, and the central midfielder and striker stepping across to reduce the space in this area also. This is an extremely locally compact structure, but because of the intense pressure from the front on the ball carrier, a switch in play is not possible. One of the main advantages of having this back three is the coverage of the back line, and so if one centre-back does step out, the defence can still be in a stable position by shuffling.

Traps in wide areas

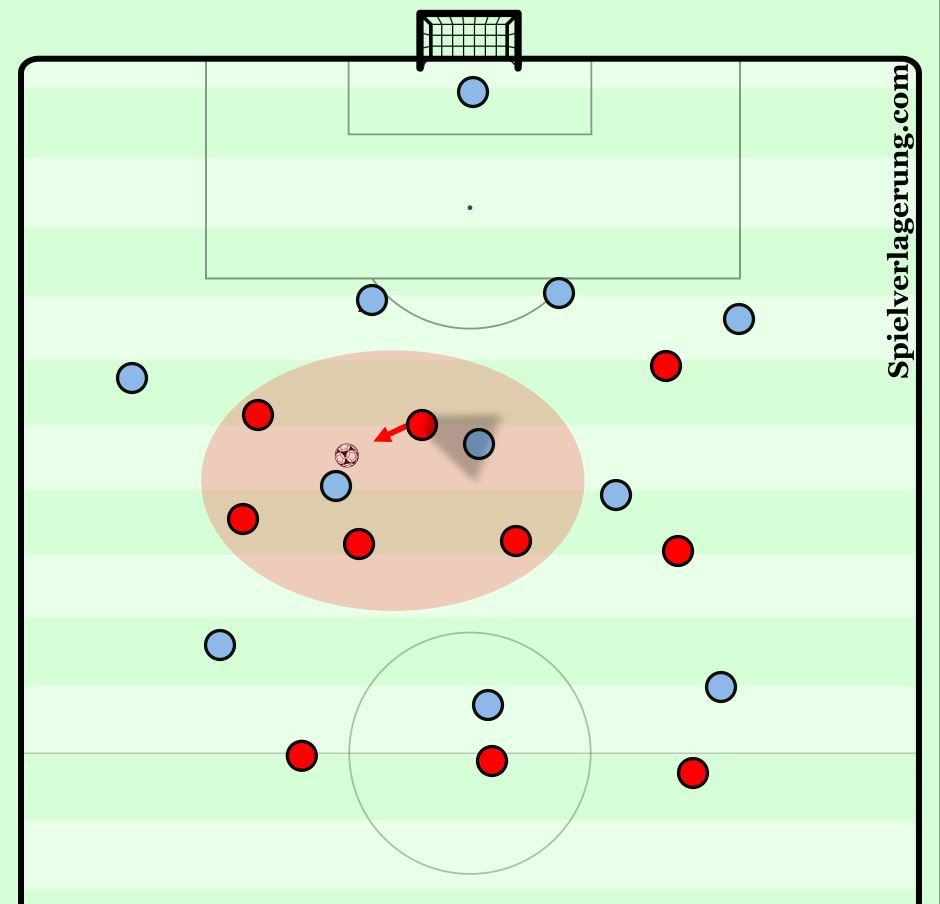

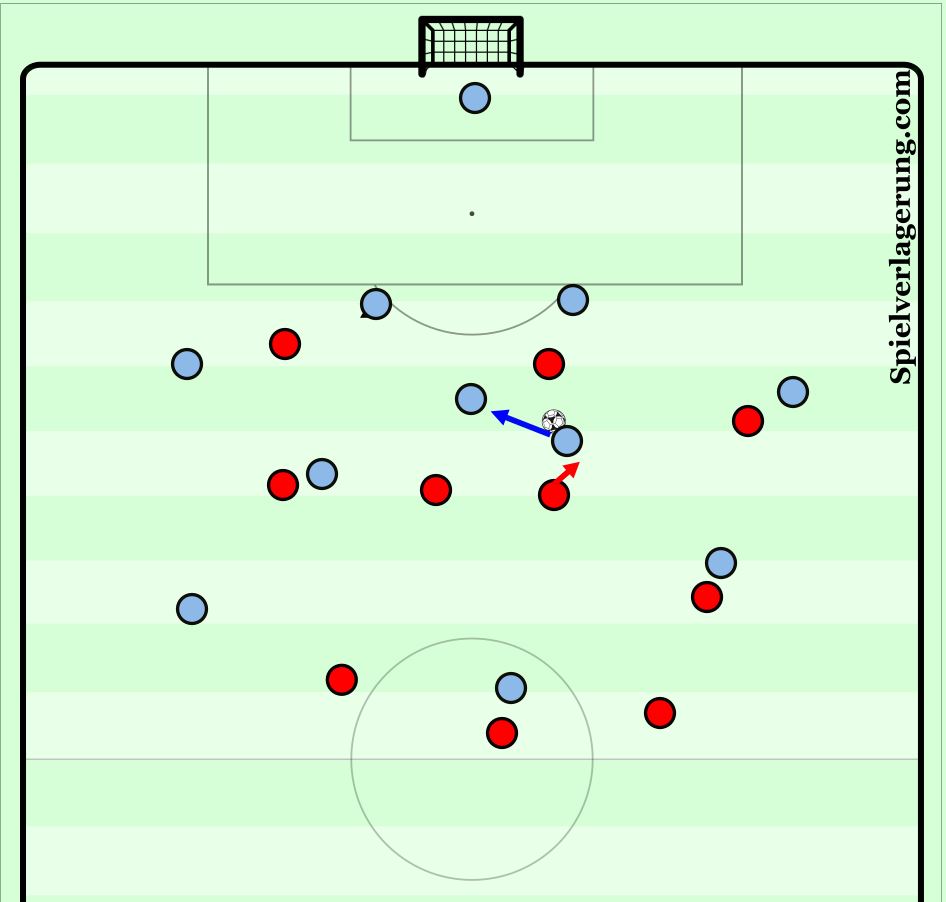

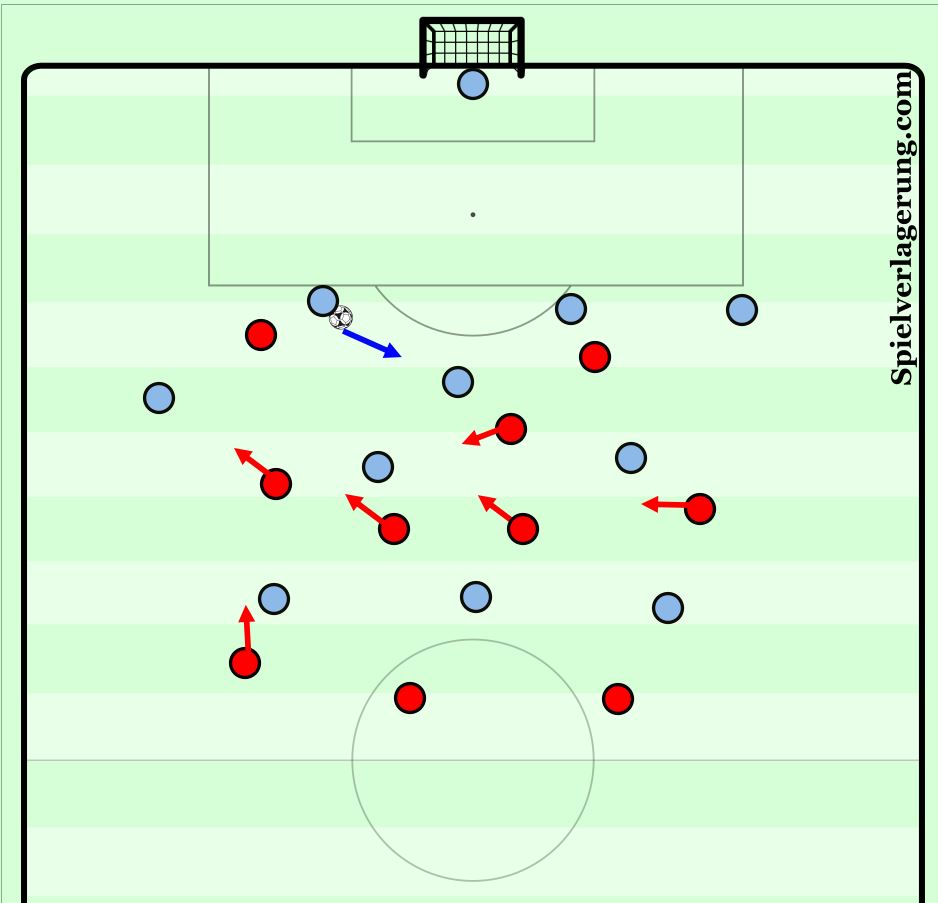

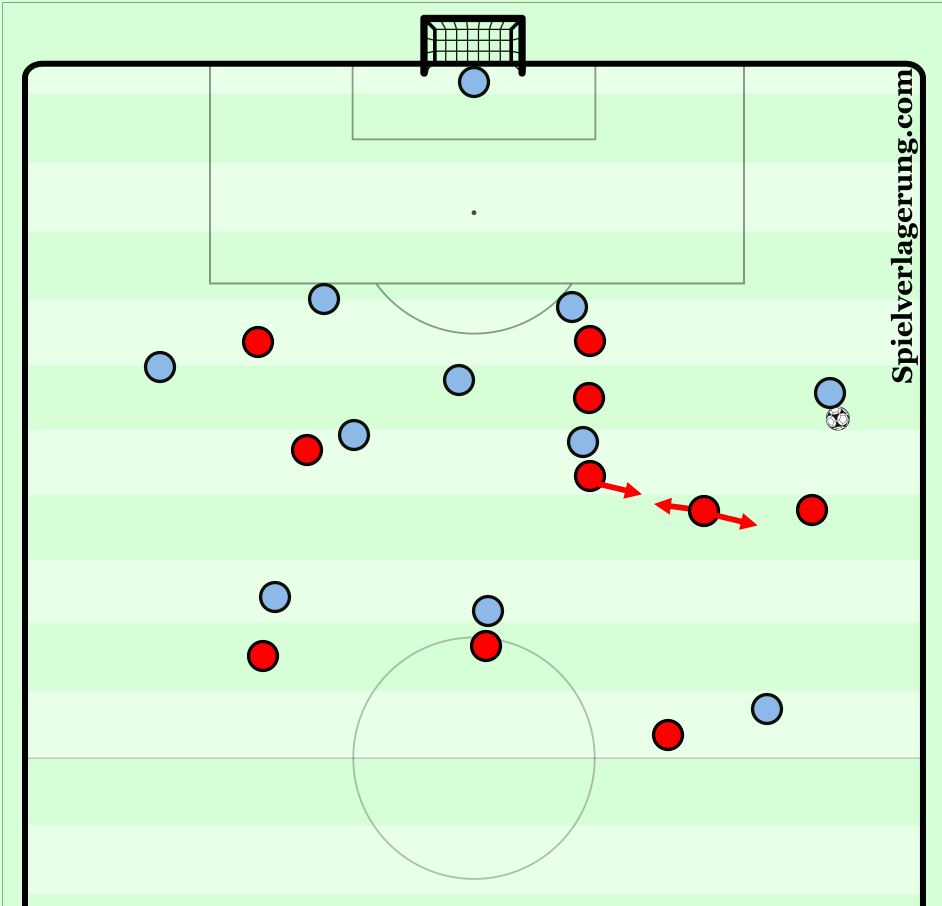

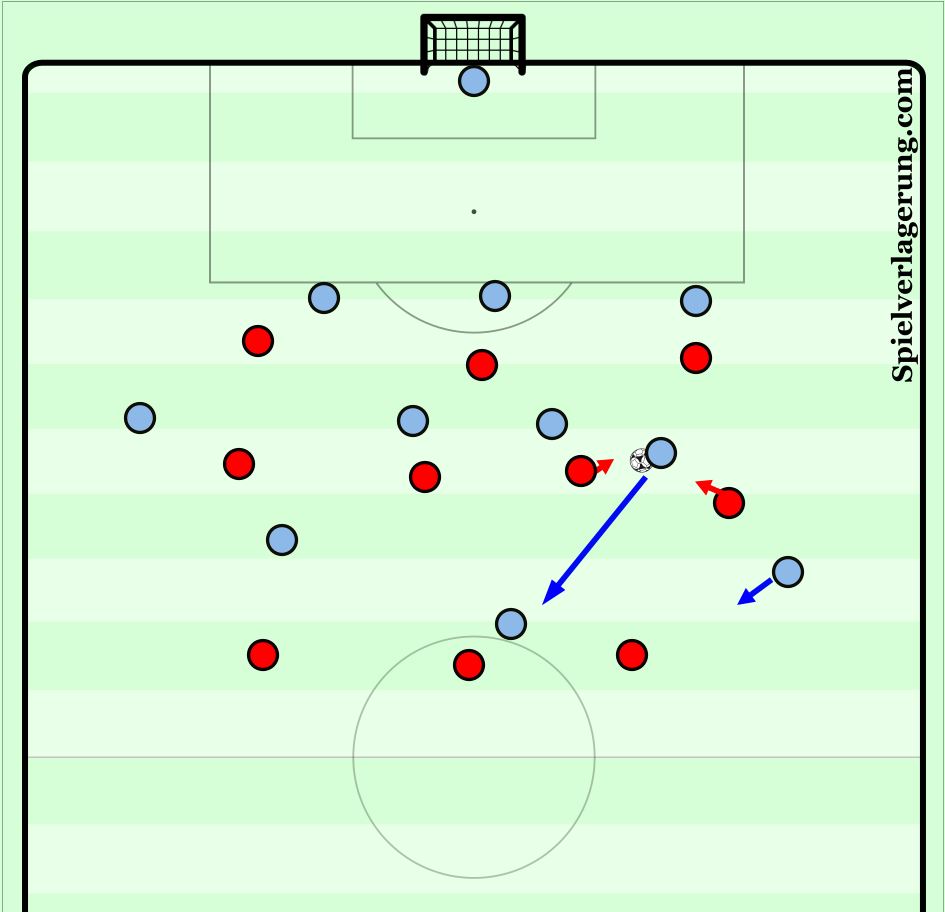

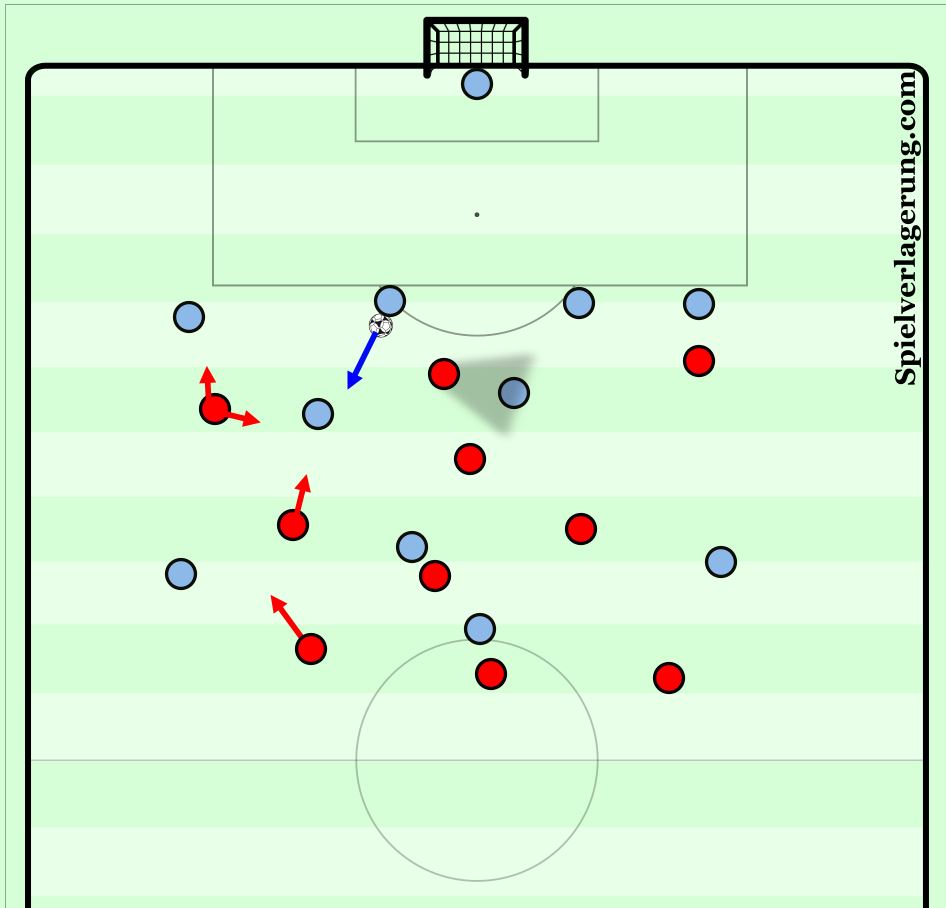

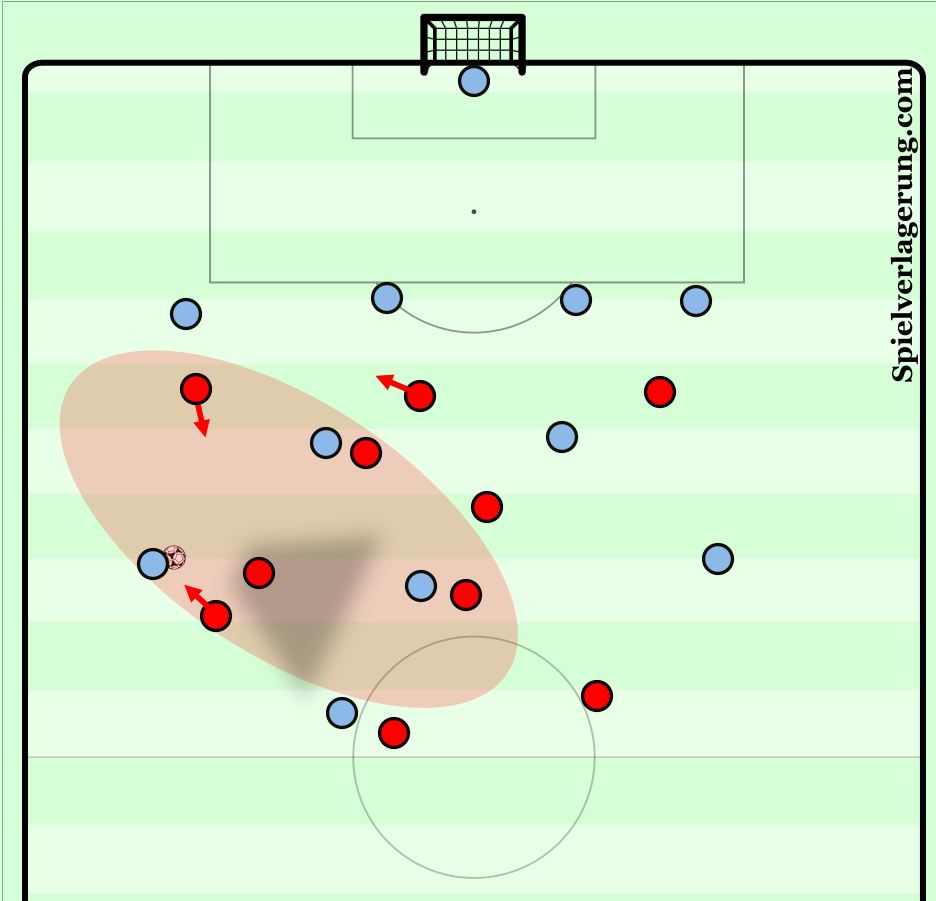

In a similar example here, we can see again a pass into the full-back being allowed again through the pivot, but with this time the centre-back playing the ball. The pivot must be given enough time to receive by the striker, and the passing lane between the pivot and full-back should be left comfortably open to allow the pass. Once the pass is received, the midfield can push across and look to trap the full-back in the wide area, using the movements seen below.

The winger will press the full-back, while the nearest central midfielder will move across to cut the passing lane into the opposition winger. The far central midfielder can then move across to mark, while the striker can then get ball side of the pivot and keep them in their cover shadow. The far winger can also move across slightly, as the threat of a switch in play is reduced due to the intense pressure on the ball carrier.

This leaves the trap in this structure seen below, with all available options cut off and immediate pressure on the ball carrier being available. Traps set in wide areas have the obvious benefit of the touchline cutting off an option for the ball carrier, whereas traps in central areas allow for more passing options for the ball carrier (and therefore more passing lanes to cut), but allow for better quality turnovers in areas that then give more passing options again.

Another pressing trap available leaves the full-back free to receive the ball through a long pass direct into a wide area. The usual right winger drops deeper to concede this space and tempt a long pass. Central options are marked tightly and the far inside forward presses in tight to the opposite centre-back, and can even double up on the ball carrying centre-back. If players can stay on the far side of their opponents when the long ball is played, a pressing trap can be set up to cut the passing lanes to the inside.

From here, the full-back is afforded some space to drive with the ball, at which point the central midfielder can jump across, also covering the passing lane inside to the striker. Because of the time allowed both by the long pass and the dribble forward from the full-back, the other central midfielder and the rest of the team can tuck over to create compactness in this area, as we can see below.

Additionally, with the winger/wing-back (number two) disguised behind the opposition winger, the same pressing trap could be set with this player pressing the ball carrying full-back, and a centre-back marking the winger should then drop short or run behind. However, the coverage of the inside passing lane to the striker is now much harder due to the pressing distances involved.

The effect of different formations on these pressing traps

One option a team has in order to aid their build-up is to stretch the lines of the pressing side. This can be done in a number of ways, but a common strategy to stretch particularly the first line of the press is to use a back three. This allows for more width and better coverage along the back line for the team in possession, and therefore gives both more players and more distance for the pressing side to cover. If the opposition moves into a 3-4-3 themselves against this pressing scheme, not much difference should be made to the pressing simply due to the numbers committed into the first line still matching the numbers in the opposition’s first line of build-up. All three centre-backs can still be pressed, with the striker now just pressing a centre-back in front of him, and with the formations now matching, players can press in a positional manner.

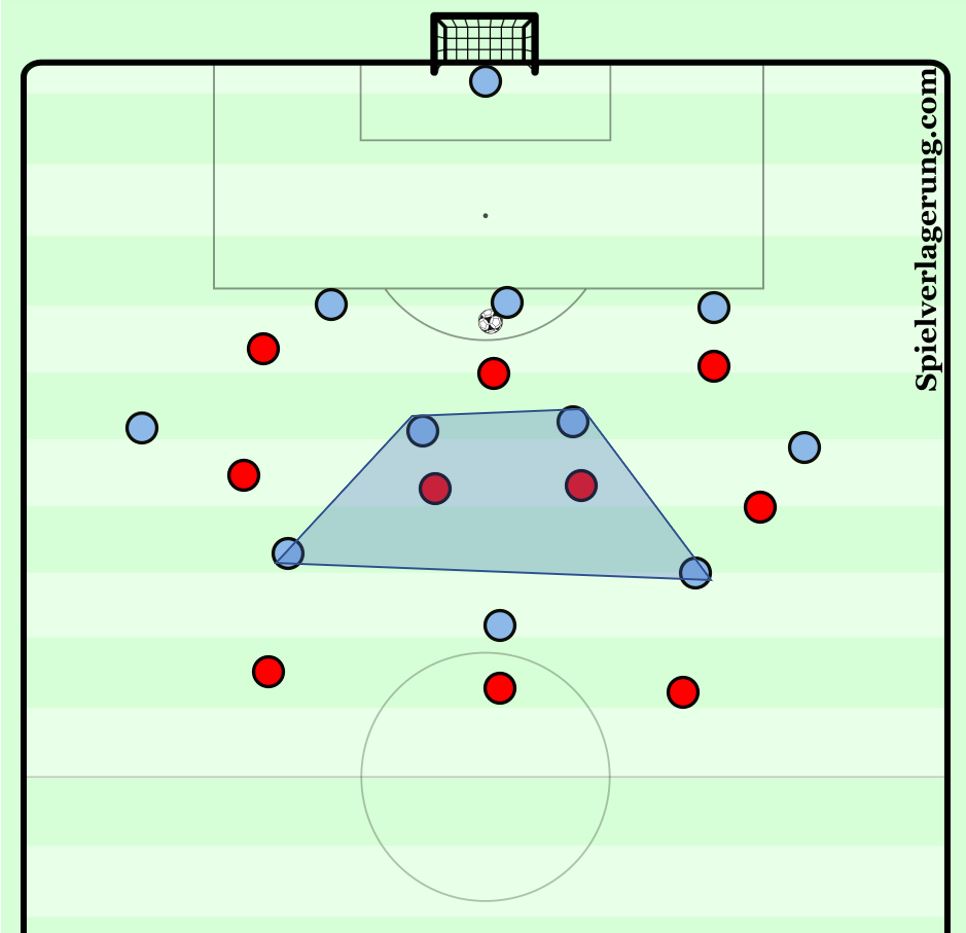

The movement and space occupation of the central midfielders is key to creating space, with the potential for the use of a midfield box within a 3-4-3. If central midfielders stay central, they open up space in the half spaces, but from a central area under pressure this pass is unlikely to be an option without deeper movement. We can see that this deeper movement to create a temporary 3-5-2 can create an overload and an opportunity to progress up the pitch away from a pressing trap. The near central midfielder stays centrally and feints to receive often, drawing their marker in to a more central area and way from the half space, while one of the build-up side’s inside forwards drops into the half-space quickly to lose their marker. A movement from one centre-back deeper helps to occupy the inside forward, increasing the size of the half space and reducing the opportunity for pressure on the ball carrier in this direction.

This dropping forward has to be fairly press resistant and technically competent in tight spaces, and the ball can then be played through the space which was vacated by the player, with the far sided forward coming across into a central position, and the wing-back moving down the line while the pressing wing-back likely presses inwards.

If the opposite movement is made within the box, another possible solution can be completed, depending on the intensity of the pressing in the first line. Here, the central midfielders move into the half spaces and feint to receive, which creates space in central areas for the inside forwards, who can then remain in higher areas. The closing of this passing lane can come mainly from the pressing striker in this scenario, and so intense pressure should be applied to this centre-back, but this can create more space if the ball is laid back.

Against a much deeper 4-4-2 Tottenham Hotspur, Julian Nagelsmann used this midfield box with both opposite space occupations used throughout. With the same number of players in the second line of the press, penetration through this line was done in the same way as outlined below, but with Tottenham having one less player within their first line, this access was made even easier.

With a number of different methods able to be completed within the same shape, it becomes difficult for the opposition to set pressing traps and read each situation and predict, and in terms of game preparation if this system is used in the build-up as somewhat of a surprise, it is difficult to prepare pressing traps. As a solution early on you would likely see the opposition become more passive, which in many ways gives the in-possession side some of what they were aiming to achieve. If the inside forwards sit slightly and now press from the front, this half space can be constricted, but more time is given to the centre-backs and increased access on the wings, where the 3v2 overload in central midfield can be exploited.

Double pivots

The most complex role within the this 3-4-3 pressing system is the role of the striker, who has to press while keeping the pivot in their cover shadow. As a result, when building up we can look to exploit this complex role and adjust the shape to do this.

As a result, dropping into a 4-2-3-1 can cause problems with these pressing traps. Dropping two players onto the same line as double pivots means that the striker cannot keep both deep central options within their cover shadow, and therefore means that one of these pivots must be passed on to a central midfielder. This is a tactic that Pep Guardiola and Carlo Ancelotti have used against Firmino’s role in Liverpool’s scheme.

Now you may think that the first pressing trap discussed in this article could then be used in this scenario, but with the different dynamics involved in the 4-2-3-1, this trap can become extremely difficult and easily overcome. With the other pivot on the same line, a lateral pass is available, with some limited pressure available. The ten can also receive in the space between the two midfielders, and the space between wing-back and central midfielder can also be exploited potentially. Each pressing player also has a number of different passing lanes to cover and therefore decisional problems may occur when considering the direction of the run, and of course both lanes can’t be covered.

It could also then be argued that the initial pressing midfielder could jump to man mark one pivot, while the other pivot is kept within the cover shadow of the striker. However, due to the depth involved within this 4-2-3-1, unless the pressing team has extreme confidence in its defenders 1v1 ability, they cannot afford for this player to push too high, or vertical compactness is lost and a 4v3 can be created.

How can you adjust?

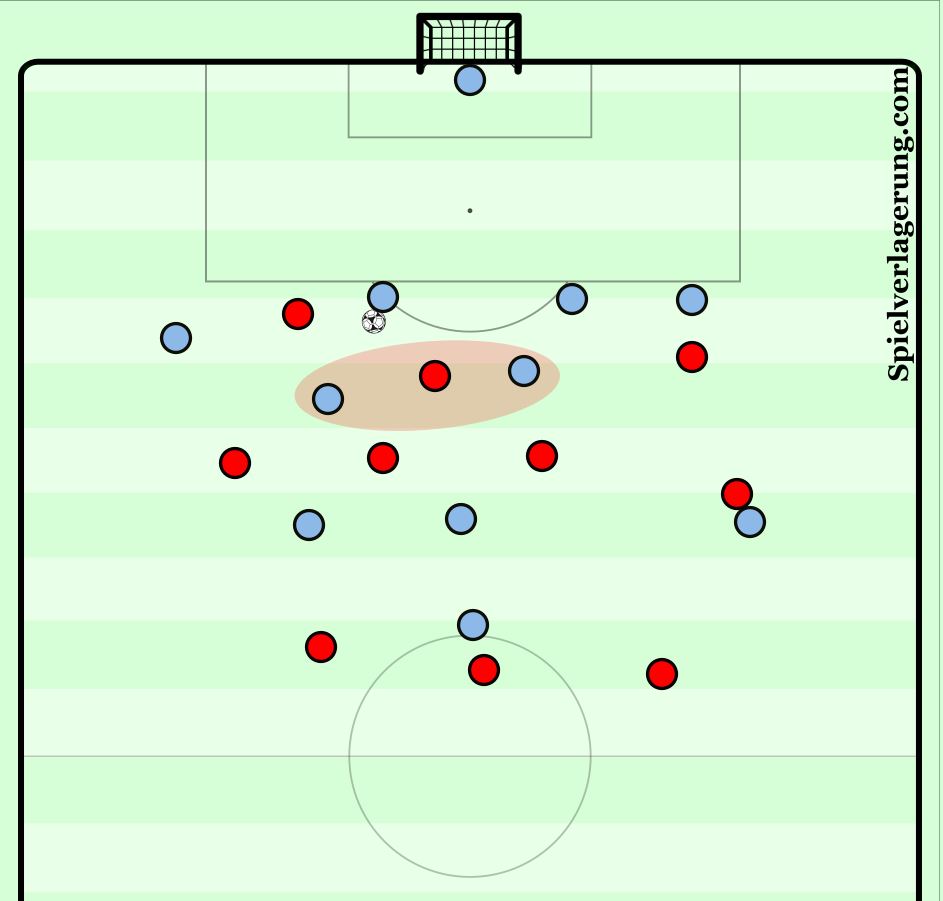

To combat this 4-2-3-1 more staggering is needed within the pressing shape to allow for angles to be covered effectively, with a 3-4-3 being typically very flat in midfield. As a result, the pressing shape can be adjusted to a 3-4-3 diamond, in which the first line is passive and looks to guard passing lanes, with the striker keeping one pivot still within their cover shadow. A central midfielder can press the pivot from behind, and there is compactness within this shape that covers the angles previously mentioned, most notably the ten is now marked.

The pressure by the winger forces the player towards the right side, whilst the central lanes can be occupied by the holding and central midfielder pressing from behind. The striker and attacking midfielder can press together to cut the passing lanes to the right, and can also press aggressively in order to prevent any high passes. These two must also remain compact to prevent a pass being played between them.

If play is switched to the other centre-back, the same shape can be created again within a few seconds of shuffling, with the basic principles of the diagonal passing lane to a pivot being cut and the straight passing option being open but pressable. Again, the winger initially cuts the passing lane directly to the opposition winger by staying narrower, but can move out to press with cover behind still. If the ball is switched quickly and played into an awaiting pivot, the central midfielder behind can jump to press in quickly while covering forward passing lanes.

Pressing trap against a 4-2-3-1

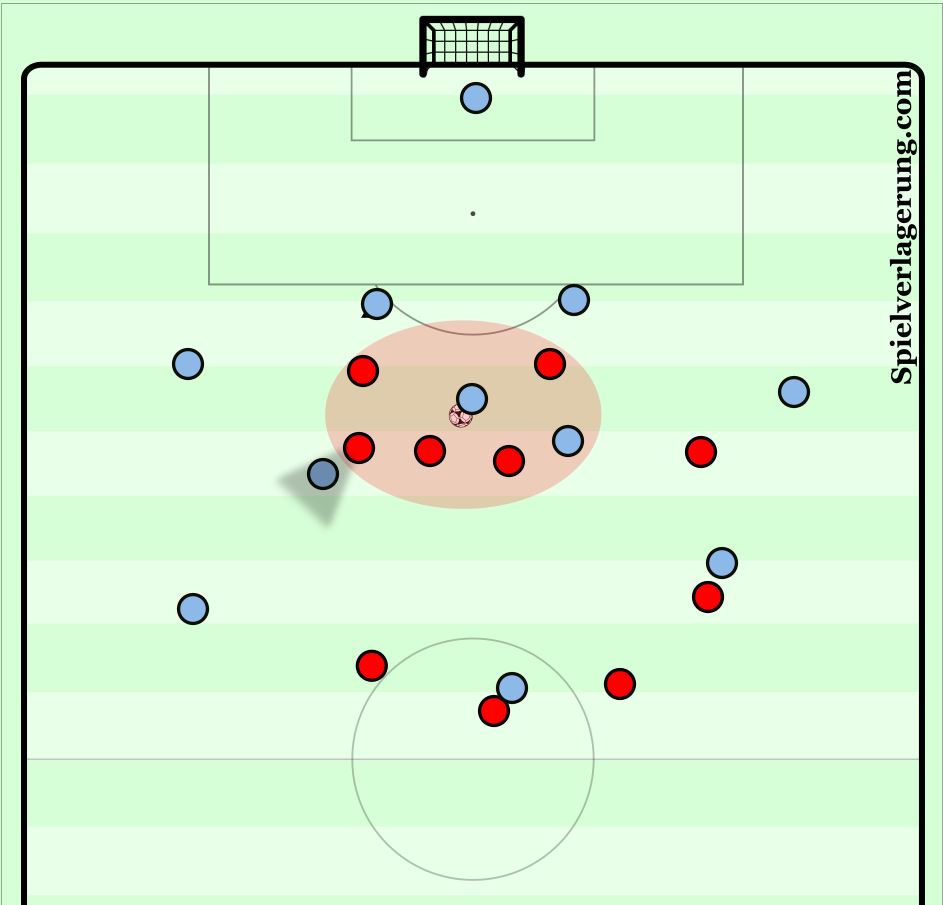

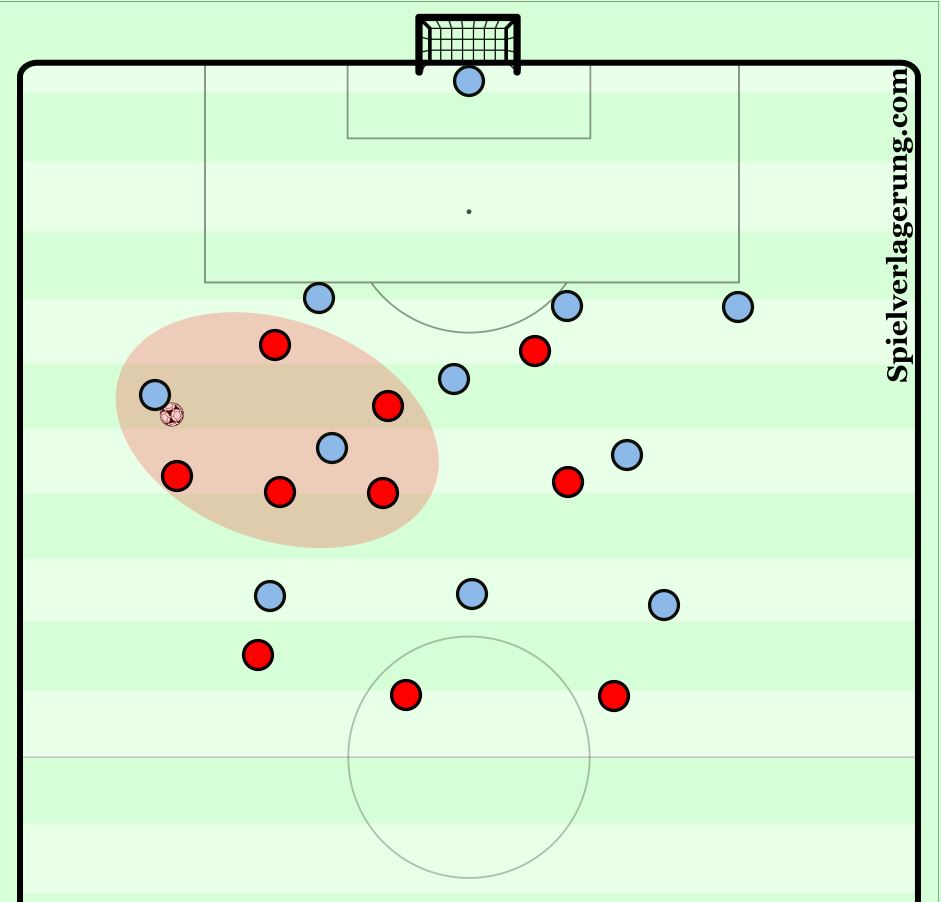

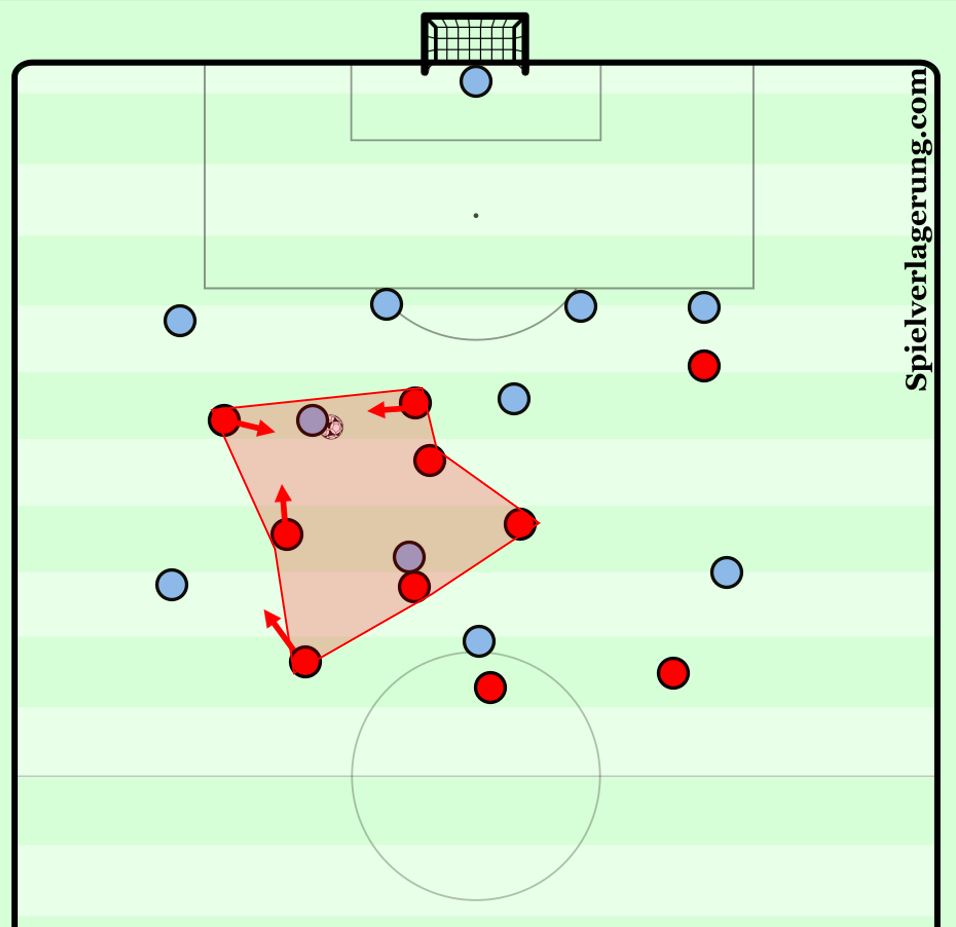

One pressing trap is still available however, if the wide forward opens the passing lane to the opposition wide forward, thanks to the now more staggered structure, a pressing trap can be created within this wide area, using the following movements highlighted below. The left sided midfielder marks the ball near pivot as close as possible to prevent them receiving the ball, while also maintaining a good distance to press the wide area. The central midfielder covers the vertical central lane, and is able to shift across into the shape seen in the next image.

The most central midfielder has the option of jumping to press onto the left sided (our left) pivot, given their proximity to the player, while the left sided midfielder covers lateral options for the ball carrier and helps cover the inside space which the six (deepest midfielder) has to cover. The higher centre-back can also press vertically, while the six can mark the ten, and can also provide cover in the backline after a centre-back has jumped. This allows for a 2v1 to be created directly on the ball carrier, and for all immediate options to be marked, which gives a high chance for a turnover. The far sided midfielder can also seal the trap further and jump in if needed, and can also cover the far sided opposition players. This also gives an opportunity for a counter-attack with the offensive structure still in a good shape and the opposition caged in.

Conclusion

Pressing within a 3-4-3 in this way offers the opportunity for efficient pressing within the first line, while also committing more players forward in higher starting positions, allowing for a greater ability to prevent the opposition building up. As highlighted throughout the article, there are also a number of pressing traps available within this formation, and of course there are many more available, as well as there being solutions in order to avoid these traps. This article should therefore have shown you some of the dynamics involved in setting up pressing traps in a 3-4-3, as well as what the advantages and disadvantages of the system can be.

Writing by Cameron Meighan; Editing by Constantin Eckner.

3 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

CT June 26, 2021 um 12:21 pm

Could someone give me some tips, on how to find pressing traps in games.

Kenan September 14, 2021 um 1:13 pm

I know this may be a very late answer to your question, but still, it’s better late than never.

If you’ve paid enough attention to the text, you probably have noticed that all of the presented pressing traps have actually been shown in the very early stage of opponents play. Therefore, what you can take from that is that you should mostly watch for them in the build-up.

Take for example Liverpool or Manchester City. Pay attention to how for example their attackers position themself when opponents are starting their play. Also pay attention to the behavior of the keeper and the centre backs of the opposing team. Not only movement is important, but also body positioning. Eventually, you will start noticing these things.

At first, you will probably have to replay same situations over and over again until actually noticing what’s going on. Eventually, you start understanding concepts and patterns and can spot them much more easily.

CT September 14, 2021 um 3:10 pm

Thank you very much. Wasn’t too late 🙂