The Evolution of Counterattacking

As we move forward through the years football continues to evolve. The developments are not often massive evolutions such as Sacchi’s zonal congestion from the 80s or Michels’ and Cruyff’s total football from the 70s, but most frequently minor positional or role adjustments within the different phases of the game. Every goal scored for your team and every goal conceded that is prevented for your team has high value – and as analytics continue to grow within our sport, we are seeing its impact on football’s phases little by little.

Set pieces such as corners, freekicks, goal-kicks, and even throw-ins are being analyzed to the finest of details both qualitatively and quantitatively. It can be observed in the latest world cup that teams are beginning to defend on average more compact as a block, “Teams at this World Cup were more compact in defence, with a tournament average of 26m between a side’s deepest defender and highest attacker out of possession. The amount of space available has been dramatically reduced, making it challenging to find openings.” – 2018 FIFA World Cup Technical Report

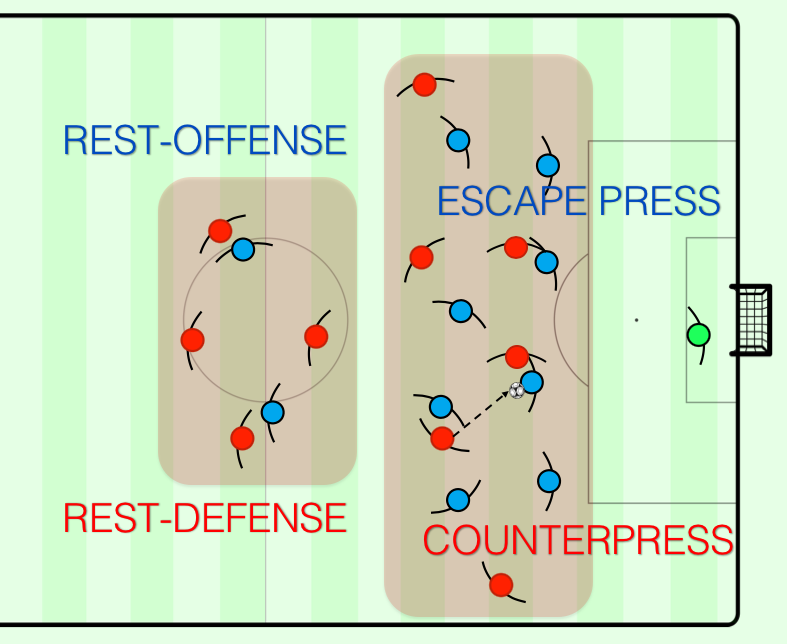

A higher number of teams are implementing aspects of a more modern possession game and taking care of the details in the defensive transition than before – with clear ideas on how and when to counter-press and set up their rest-defense.

Many goals have always resulted from the offensive transition moments through the history of football, but we are beginning to see an evolution even in that phase of play to make it as efficient and dangerous as possible. With teams improving overall in their defending, the counterattacks need to be even faster and more precise than in the past. In this tactical theory article, we will take a look at how counterattacks have developed over the years to where we are now with leaders such as Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool FC as the modern example.

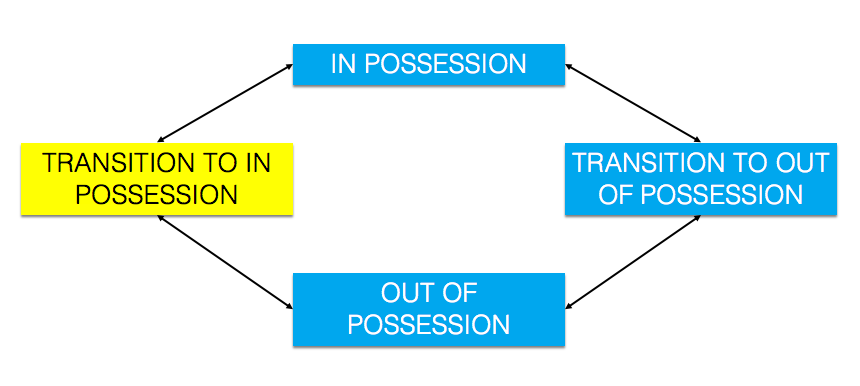

The Counterattack

To put it simply, a counterattack is when a team attacks immediately after regaining the ball from defending the opponent’s attack. As the opponent team loses possession of the ball, they are moving from a structure that allows them to better attack the defense into a structure that allows them to better defend the attack. In this short period of time, the team which is winning the ball can attack the opponent’s transitional organization before they get back in position to protect themselves more effectively.

The same principles of attack apply as when you are in a positional organization, but it is typically done faster and with different structures between the teams. Players seek the immediate ball in behind the defense to a free striker or winger, a pass directly into a free attacking midfielder between the lines, or passes into the feet of the marked forward(s) to create a lay off pass to a forward-running teammate just as they normally would.

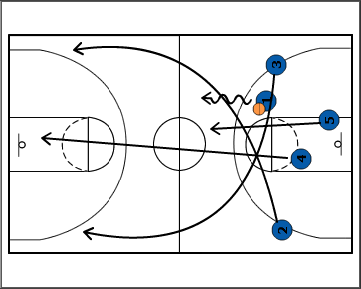

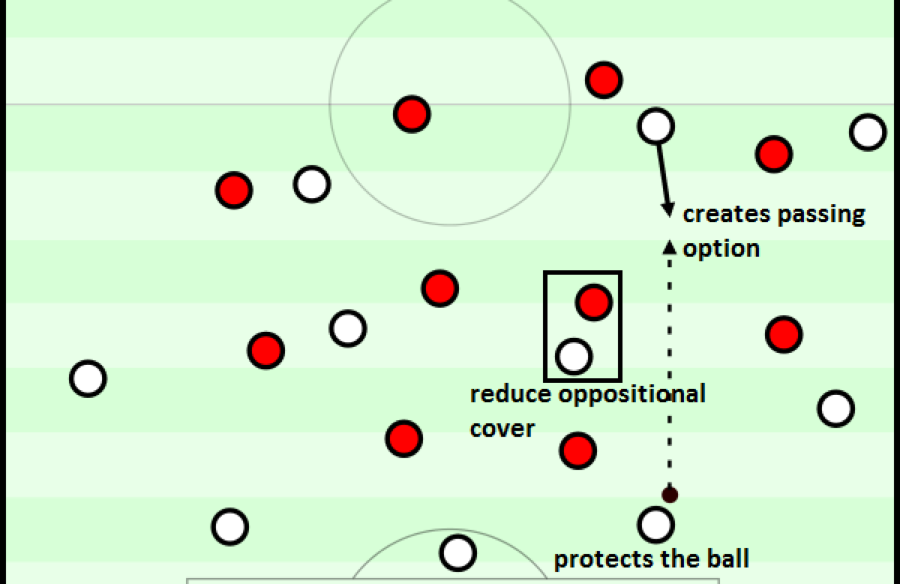

Players with the ball run forward until there is pressure or if there is a teammate already in a better position and then pass the ball or dribble past the opponent, players off the ball look to get open for passes toward the opponent goal and reduce the cover the opponents have through spacing. It is all simply done in the context of a transition between attack and defense. In transitions, a team will normally look to fill the center, right and left channels with runners to provide passing options and reduce cover – similar to the concept of “filling the lanes” in offensive transition in basketball.

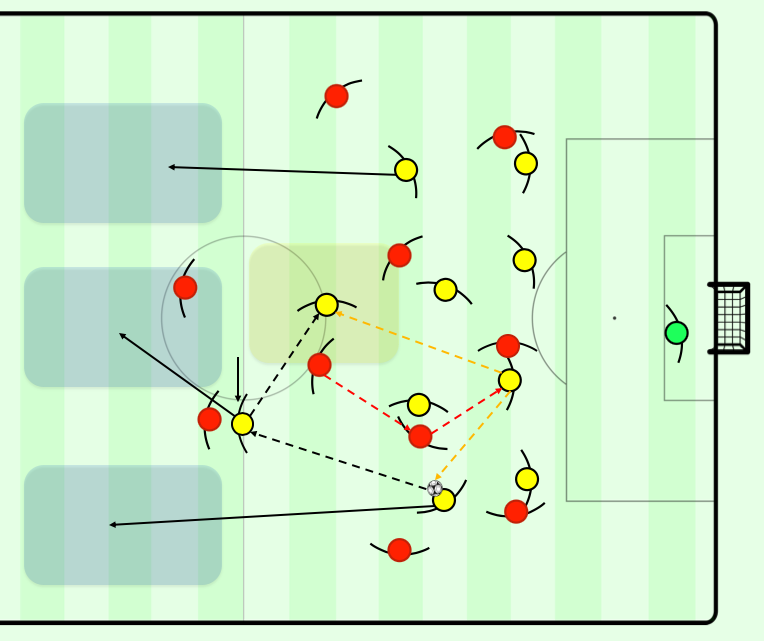

When analyzing counterattacks and structuring each general possibility, 7 basic patterns can be found:

- Long pass into the feet of the central striker to lay off the ball to a forward-running central attacking midfielder, the striker then spins out to fill one of the wider channels while a midfielder looks to arrive forward and fill the opposite channel.

- The striker can also look to fill the center if both wide channels are being filled.

- Long pass into the feet of the central striker to lay off the ball to a forward-running winger, then striker then spins out to fill the central lane while a midfielder looks to arrive forward and fill the opposite wide channel.

- Long pass into channel for a central striker to run out into depth onto with speed against the central defender – teammates will look to fill the center and the opposite channels to be available for a pass if a shot isn’t possible.

- Long pass into channel for a central striker to run out and receive into feet with protecting the ball from the defender – teammates (can be an underlapping winger, attacking midfielder, etc.) will look to fill the center and the opposite channels to be available for the lay off.

- Long pass immediately into the wider channel for wide “lurking” striker or winger running into depth behind opponent wide defenders – teammates look to fill the center and opposite channel if possible, to arrive for a pass.

- This high and wide player may receive the pass into feet if a run into depth toward the center is covered, in which case they can look to lay off into forward-running teammates underneath them, in the center, or switch the ball to the opposite channel

- An attacking midfielder or second striker receives the ball in the center in front of the opponent defense (playmaking position) and then plays the striker or forward-running wide players through the channels behind the defense.

- A forward or attacking midfielder recover the ball in a deep position and can dribble directly at the opponent defense for a long distance (ball is picked up past opponent midfield) – teammates look to fill the open lanes around the dribbler, the dribbler can shoot or look to pass or cross into the other lanes.

As transition defenses have begun to evolve to better cover the counterattacking outlets of the defending team and apply pressure immediately when the ball is lost, more precision (due to tightened spaces) and more speed (due to lessened time) have been required from counterattacking teams.

Counterpressing has allowed teams who are losing possession of the ball in the opponent half to defend where they have more players (in the offensive zones) and win the ball quickly to maintain their field position and continue the attack which they have worked to build up to that point, at times even having a better chance of breaking through the opponent after recovering the ball from a counter-press due to the opponent players beginning to move forward with the idea to counterattack – leaving them slightly out of position to protect their own goal.

In the past, there was less widespread implementation of a focused counter-pressing or rest-defense game, which allowed defending teams to win the ball and then more consistently hit their opponents on the counter. This not only meant chances to attack, but it also meant changes in field position and domination over the game. Even the “more dominant” teams would have to run back into their half more often to protect their goal. The game moved frequently from Team A’s attack on the goal to Team B’s counterattack on the opposite goal, Team A’s defense of their own goal, to Team A’s counterattack, and so on. This stretched the overall distances between the players in each team, resulting in more open and crowd-pleasing matches.

In response, instead of applying immediate pressure to suffocate opponent counterattacks, coaches began to develop ideas on how to defend against opponent counters better. Mourinho for example famously spoke about that he always sought to have 5 players prepared in deeper positions for the opponent counterattack. Bielsa has mentioned that he prefers to have 1 more player in a defensive position than the opponent has attackers. Coaches could vary on if they approach this concept of rest-defense in a more numerical, “man-to-man,” or “zonal” manner.

This approach more effectively prevented breakthroughs behind the defense when opponents were counterattacking but did little to prevent the opponent from progressing into the opposite half of the field to begin their positional attack if they had not been fast enough to expose the transitional organization of the retreating team.

In the modern game, the top teams are showing their ability not only to cover the potential breakthroughs behind the defense of counterattacks but also to apply immediate pressure on the counterattack to prevent it from ever being born in the first place. This created far longer periods of attacking in the opponent half for the more dominant teams (i.e. Pep Guardiola’s Manchester City). Counterattacks would need to evolve if they were going to more consistently escape pressure and break behind the opponent’s transitional organization and domination over the game.

The Classic Counterattack

If we look at the last two decades of football overall, the most popular formations have been variants of the 4-4-2, 4-2-3-1, and 4-3-3. These would typically result in 4-4-2, 4-4-1-1, and 4-1-4-1 out of possession respectively. Typical counterattacks would arise out of these defensive formations – Peter Krawietz, Jurgen Klopp’s assistant coach and video analyst (also known as “The Eye”), has said in the past that Liverpool had to move past the “classic, random counterattacking situation” and create something more systematic. Meaning, counterattacks would simply be a result of fast forward progression of the ball in transition from these deeper and more defensive shapes, with no seemingly explicit or clear method of creating the counterattack itself.

This resulted in counterattacks that relied heavily on the striker(s) and/or the attacking midfielder to receive the ball and progress the team forward, while the wingers and central midfielders may or may not arrive in time to support the transitional attack. With talented players and willing runners, this is normally enough to create very dangerous attacks in this short window of time.

If we take teams such as Atletico Madrid under Diego Simeone or Leicester City under Claudio Ranieri for example, they defended in compact 4-4-2 formations which were more often in the midfield or defensive portion of the field. Once the ball was won, they sought to progress very quickly into their front 2 players to launch a counterattack. Based on the profile of the players, the method of attack would be different. If you have a striker such as Jamie Vardy who is extremely fast and with intelligent movements, the team would look immediately to play the ball into depth on the side of the field which Vardy was running into out of the center while the opposite striker and winger filled the center and opposite channels.

If you have a striker such as Diego Costa who is fast with good movement in his own right (especially when he was younger), but physically a larger and stronger player than someone like Vardy – the team may look immediately to play the ball into the feet of Costa in the center or in the channel as he shields off his defender so that he can lay the ball off into his partner striker, an attacking midfielder, or even midfielders/wingers running from their deeper defensive positions.

If we consider a team such as Borussia Dortmund under Jurgen Klopp for example, they also defended in a 4-4-2 or 4-4-1-1 very often, but with an attacking midfielder rather than another striker. Players such as Mario Gotze or Shinji Kagawa would move in support of the main striker such as Robert Lewandowski. When the team would defend in their compact midfield block and then win the ball, they could look to find Mario Gotze in a pocket of space behind the opponent midfielders in a “playmaking position” to then run with the ball toward the goal and play the striker or wingers running from deep into the channels outside the central defenders and behind the defense. The team may also look for a ball directly into Lewandowski so that he can hold the ball up (such as Costa in our earlier example) and then play it into Gotze to dribble forward with speed or into a winger arriving from a deeper position.

These counterattacking methods rely on your few forward players in the rest-offense or rest-attack (meaning, the portion of your team not directly interacting with the defending play and can look to be outlets for teammates escaping the opponent counter-press) to receive, pass, and dribble well against a higher number of defenders through the center of the field. An evolution we began to see more often in football for the dangerous counterattacking teams is the purposeful use of the “gambling” winger.

The “Gambling” Wingers/Inside Forwards

A “gambling” winger or inside forward is one that purposefully omits their defensive duties on their side of the field in order to better position and prepare themselves to attack the opponent as soon as the ball is won. This can happen in most teams randomly throughout a match as a winger is late to get back into defense, but what makes it a clear strategy is when both the coach and the player understand this role. The coach tries to make systematic adjustments to the rest of the team to cope with the lack of typical defensive presence, while the player is more actively looking for space to exploit and not worried about having to run back and join the team every time.

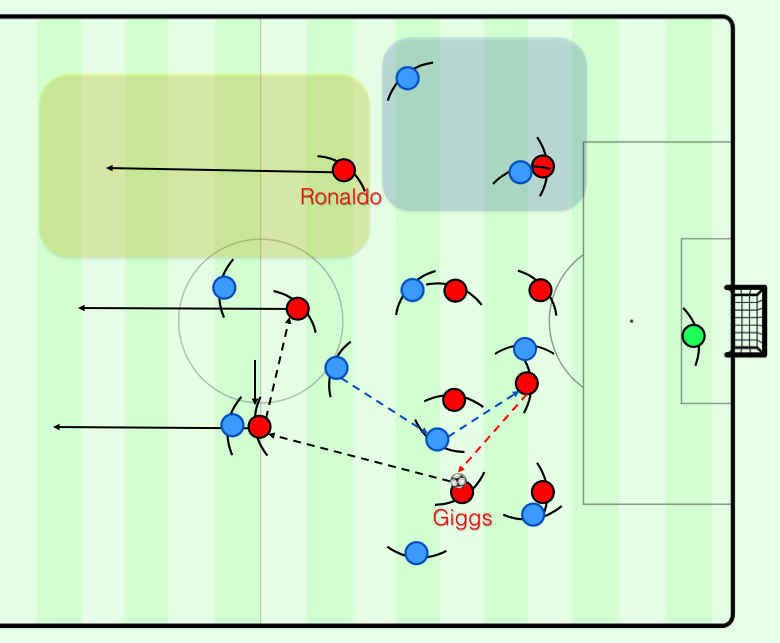

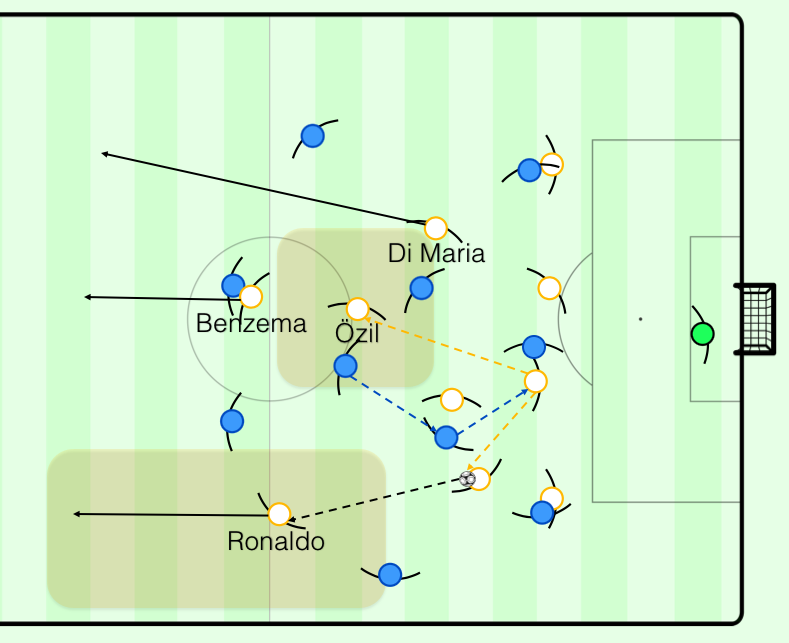

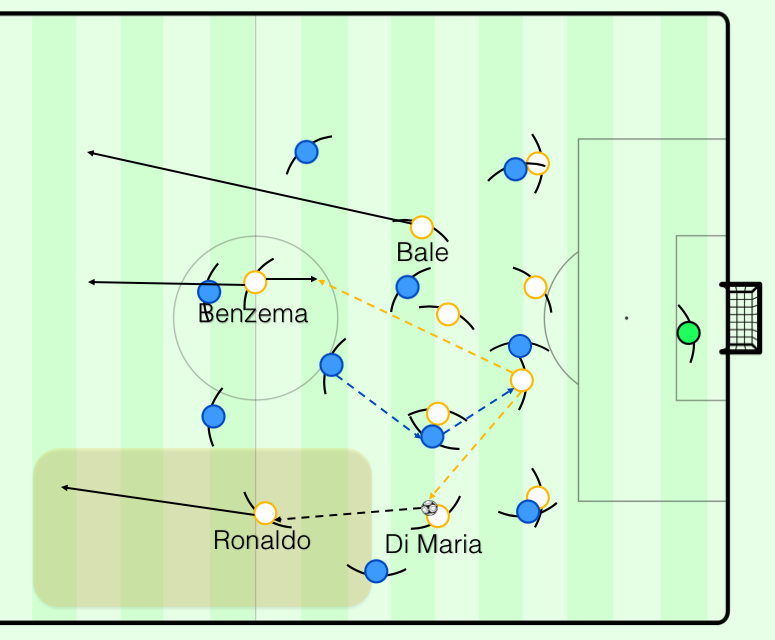

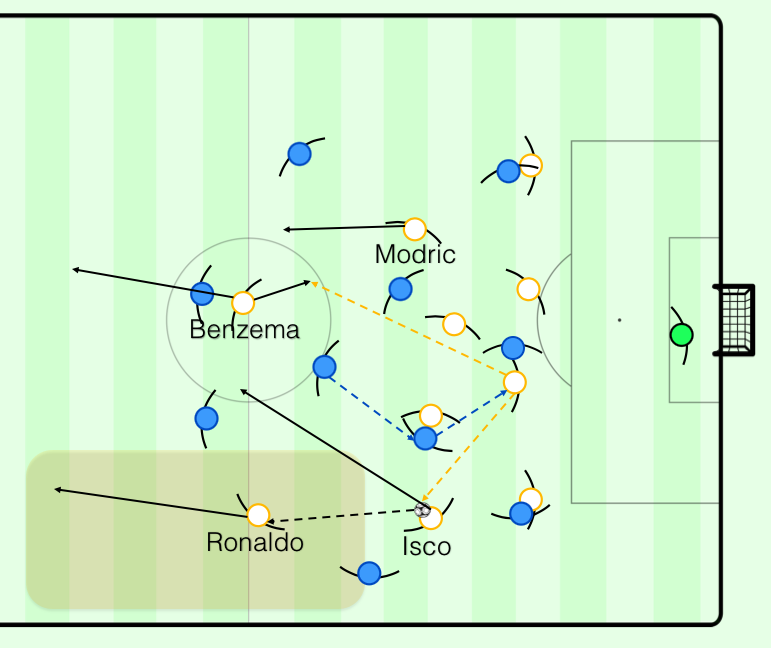

The best example of this role for counterattacking teams is Cristiano Ronaldo both at Manchester United and Real Madrid. While many of the goals Ronaldo scored were from attacking crosses in a positional organization or set pieces such as free kicks, penalties, and crosses from corner kicks, he owes many of his best chances to score to his role during defending and counterattacking.

Another (more recent) example of this role would be Kylian Mbappe with the 2018 World Cup winning French national team. His role in defending and counterattacking as the right-winger allowed him to be more immediately prepared to threaten into depth on the wings when his team won the ball, resulting in many dangerous attacks for him during his breakout performances in the 2018 World Cup.

Using a wide player which remains forward and lurks for the weak points in a team’s transitional organization allows for more offensive presence than what we detailed as a “classic counterattacks,” and with more immediate offensive threats in this phase of the game, the likelihood of a successful counterattack goes up, the compromise is how a team handles the defensive phase.

With France’s 2018 team, on the opposite flank of Kylian Mbappe was Blaise Matuidi, a player which normally played as a defensive midfielder or a “box to box” central midfielder – meaning it was far more natural for Matuidi to provide more defensive cover and tuck into the midfield to form a line of 3 with central midfielders N’Golo Kante and Paul Pogba. This made it less dangerous for the defense when Mbappe would maintain a higher position on the right flank while Antoine Griezmann and Olivier Giroud were the striking duo through the center, with Griezmann acting more like a second striker or playmaker while Giroud was more of a target man who used his body to block defenders and used his combination ability to set up his teammates. What normally would have looked like a 4-4-1-1 looked more like an asymmetric 4-3-1-2 or 4-3-2-1, providing more offensive threat in transition.

At Manchester United, Cristiano Ronaldo had Ryan Giggs on the opposite flank to balance his higher positioning. At Real Madrid, he had players such as Angel Di Maria, Gareth Bale, and Isco Alarcon who would balance his higher positioning by dropping in next to the deeper central midfielders. At Manchester United, Sir Alex Ferguson sought to defend most often in a 4-4-2, and with Ronaldo staying higher the shape more often looked like an asymmetric 4-3-3 shape as Giggs tucked inside. Under Mourinho at Real Madrid, the team most often defended in a 4-4-1-1, but with Ronaldo remaining higher it more often looked like an asymmetric 4-3-1-2 or 4-3-2-1 as Mesut Ozil was the attacking midfielder and Karim Benzema or Gonzalo Higuain was the striker. Under Ancelotti at Real Madrid, the team looked to defend in a 4-1-4-1, but due to Ronaldo lurking higher in the left channel and Bale dropping deeper on the right flank, the team looked more often like a lopsided 4-4-2. Finally, under Zidane at Real Madrid, the team began using a 4-3-1-2 system in which Isco was the attacking midfielder. When out of possession Isco would look to drop into the midfield line to form a 4-4-2 and allow Ronaldo to remain higher.

When a team is defending a fast counterattack, they will prioritize the center of the field as it’s the most direct path to goal – from there they will try to force the play wider and delay the attack (or win the ball if there is a possible moment to tackle) until the rest of the team can join the defense and re-organize. Because there are fewer defenders when trying to stop a counterattack and a focus on protecting the center, counterattacks do not have to be very wide to stretch defenses in this phase. You will rarely find a counterattack that has extremely wide forwards (toward the touchlines) getting in behind, rather the wide players in a counterattack are usually at the width of the box – just inside of space between fullbacks and center backs.

For this reason, when a gambling winger or inside forward is added to the typical 2 forward players in the center, it can create overload problems for a transitional defense. Either a team keeps more players back when attacking and has less offensive presence, or they risk the extra forward exploiting space behind the rest-defense. The space most often exploited by these players is the spaces behind fullbacks that move higher in the possession and offer width, leaving them with a large distance to cover in a short amount of time to get back and prevent the gambling winger from getting free. Gambling wingers are typically played deep in behind the defense with the first or second pass due to being immediately free.

More recently we have seen a team that created a pressing scheme (as opposed to a covering scheme like with the gambling wingers) that purposefully puts the fastest and most threatening scorers in the team in dangerous counterattacking positions for immediate passes behind, but without having to gamble with defensive solidity.

The Modern Approach to Pressing for Counterattacks

This team would be Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool FC. As I mentioned earlier, Peter Krawietz had spoken on the topic of the classic counterattack vs. a more systematic approach, here is his full quote from Raphael Honigstein’s piece on The Athletic:

“We realized how unbelievably fast Salah was and thought a lot about ways to bring his strengths to bear on the pitch. In order to get the most out of his ability to go deep, we needed to move beyond the classic, random counter-attacking situation and instead prepare situations for him systematically…You can structurally reduce the attacking game to two or three typical situations.

Assuming the opponent has the ball, we need to talk about active defending. This doesn’t mean protecting your own goal but trying to create situations in which you can win the ball. In the back of your head, you always want to exploit these situations, be it high up or in the middle of the pitch. Once you win the ball, automated procedures kick in: If you defend systematically, you know where your team-mates are.

You can then steer the opponent’s build-up in the direction you want them to. You are setting up situations you will have crafted during the preparation for the match. You know how the opponent is building up and you know whether they are taking the full-backs forward or not.”

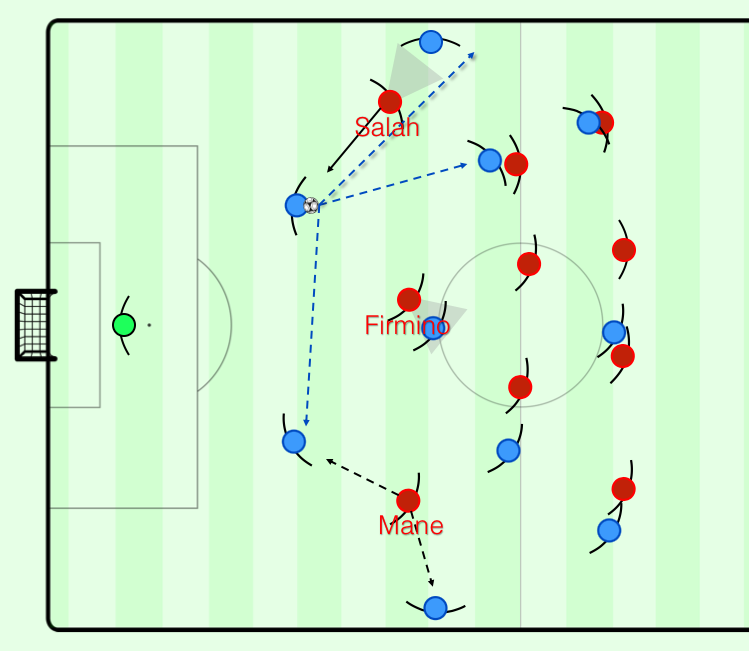

The 3 situations which he mentions in this quote for attacking are: counterattacking situations, build-up situations against a press, and circulation against an organized deep block in general. It is clear that Liverpool seeks to prepare situations not only for Salah but also for Mane in a systematic fashion. They don’t simply leave Salah or Mane in offensive positions to gamble and have the rest of the team cover, but they actively apply pressure and cut off passing lanes in a way that both these forwards are being used in the defensive scheme while at the same time being positioned to exploit the spaces behind opponent fullbacks instantly if the possession of the ball turns over.

The team seeks to lessen the time and space the opponent has on the ball to win it back earlier and then exploit their transitional organization. The gambling winger approach as detailed above relied on the rest of the team working to cover for the extra offensive player, and more often the team would defend deeper. In this case, the entire team works as a unit and can maintain a higher field position while actively forcing opponent mistakes rather than covering options and waiting for a mistake. As Krawietz mentions, when the ball is won the counterattack can be automatic because the team defended in a systematic fashion to have Salah and Mane in dangerous positions.

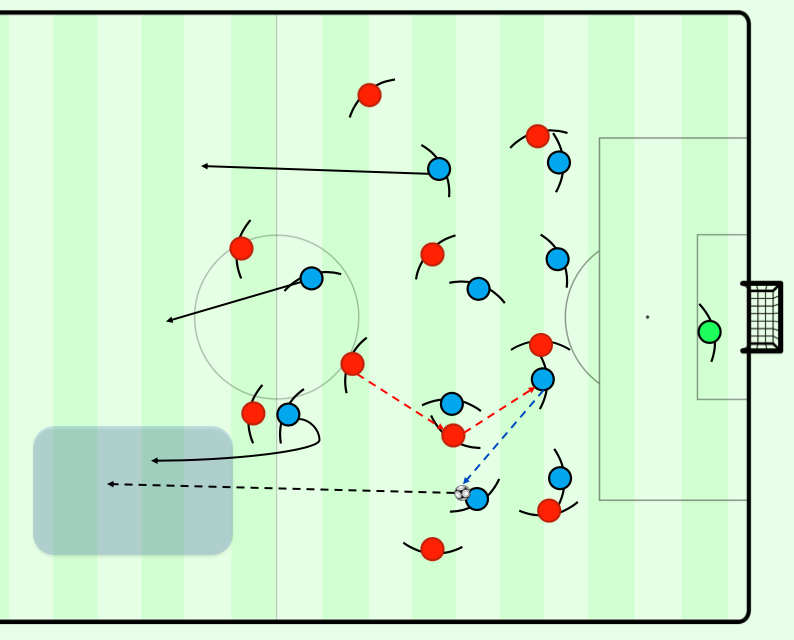

Liverpool presses in a clear 4-3-3 formation, the wingers remain in higher positions rather than dropping next to the central midfielders in this scheme. The central striker, Roberto Firmino, has the main role of dropping deeper to cover the opponent defensive midfielders while the 3 central midfielders look to cover the center and press out to the wings should the ball arrive there – this effectively creates a diamond in the center of the pitch. The back 4 remains compact and connected to cover the opponent strikers and wingers if a situation arises where the fullback or center back need to press higher into midfield to cover an open opponent, the rest of the back 4 shifts across to form a compact back 3 towards the ball.

The main role of the wingers, Salah and Mane, is to steer the opponent’s build-up as Krawietz mentioned. Their main focus is to position relative to the opponent’s fullbacks and then press toward the opponent’s central defenders while covering the passing lane to the fullbacks. This creates an interesting situation for opponent fullbacks – the central midfield 3 of Liverpool are in the middle of the field and your winger just left you to go and press a central defender. This leaves more space for you to receive the ball, so you push higher. The only problem is that the winger is blocking the direct passing lane into you – so in order to reach you, your central defender will have to play a high pass which takes longer to drop onto your feet, or play into the center of the field in order to get the ball out to you.

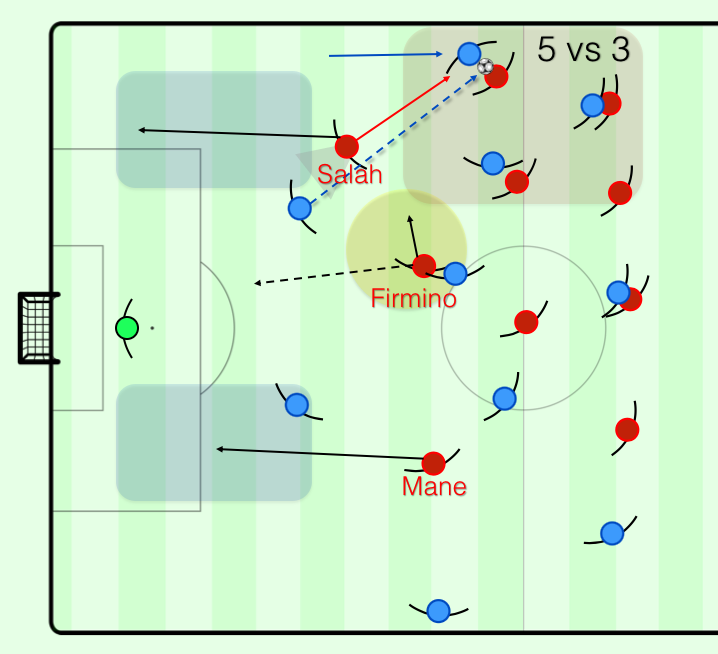

If the central defender chooses the first option and chips the ball over to you, the nearest central midfielder immediately sprints out to you while Liverpool’s defensive midfielder (typically Fabinho) covers the pressing central midfielder’s initial position. Firmino is still covering the area around the defensive midfielder and now the winger (for this example Salah) turns around and starts closing down toward the ball while blocking a back pass into the central defender. A double-team is fast approaching you on the wing without a clear possibility to back pass as Liverpool forced you forward and away from your goalkeeper or central defenders and all other passing options into the middle of the field are covered due to the diamond. It is a pressing trap! If the ball is recovered by Liverpool Salah and Mane are already positioned higher than the opponent’s fullbacks and wider than the opponent central defenders, the solution is usually an immediate pass into depth in the channel.

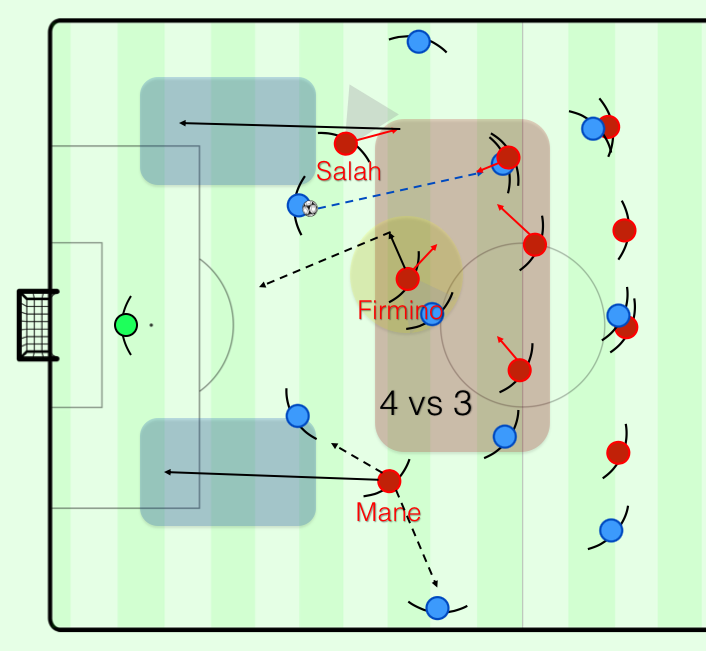

The central defender plays the ball over Salah and into the fullback, Liverpool’s central midfielder shoots out to press the ball as the spare man (i.e. Fabinho) covers him to keep all options into the middle marked. Salah now turns and blocks any back pass while coming closer to create a potential double-team on the wing while Firmino still patrols the defensive midfield area of the opponent. As the team shifts over it can create a 5 vs. 3 (if the near side central defender is free as well) or a 4 vs. 3. When the ball is won Firmino is immediately getting open as a playmaker while Mane and Salah are already in high positions behind the fullbacks due to the pressing system and can be played down the channels against the central defenders!

This is what Krawietz means when he says Liverpool seeks to set up situations that they crafted in preparation for the match, the team is prepared for how the opponent is building up and know whether the opponent’s fullbacks push higher or not.

If we look at the second option for the central defender, he chooses to pass into the center of the field as the winger is coming towards him to press. The pass into the fullback is too dangerous, the pass back to the goalkeeper isn’t necessary, and the switch to the opposite central defender or fullback seems dangerous as Mane is covering a position between the two far side options – so the clearer option is a pass forward into midfield. Because Liverpool has a diamond in the center of the field, they typically have an overload – so they react very aggressively on any pass into the center of the field while having extra cover from a free central midfielder. The central midfielder can’t pass backward out of pressure as Liverpool’s wingers just pressed from there. If you manage to keep the ball during the reception of the pass and intense pressure, you can play it wide to the open fullback…but then a similar situation to the first one can occur if the players are not fast and clean enough in their execution. In theory, this pressing scheme covers the most dangerous options while having players in dangerous positions to counterattack immediately. In practice, it has proven extremely difficult to beat Liverpool, not only due to their great possession and counter-pressing game but also due to this pressing scheme for their counterattacks. It cannot always be executed perfectly by them, but with high intensity in their running and the mentality to cover for any mistakes, it is very difficult to exploit them even when they don’t properly execute their pressing.

Side note: the positional, numerical, individual, and dynamic superiorities found in positional play can also be applied to pressing phases of the game!

The central defender chooses to play a straight ball into midfield with a Liverpool player tight on the receiver’s back and expecting the bounce-pass out wide (even if the pass gets through, Liverpool could seek to create their pressing trap on the wing detailed above), and so he plays aggressively on that side – this leads to tackles and interceptions of the ball through the middle should the central midfielder try and play out to the fullback. If the receiver turns toward the middle, the spare man is able to closely support while the surrounding players also collapse on the ball in order to trap the ball and win it inside the center of the formation. From there Firmino again looks to become the playmaker while Salah and Mane look to exploit the channels due to their high positions when blocking the central defenders from the fullbacks as above.

While Liverpool typically has Firmino in the central playmaker role and then Mane and Salah in the depth striker roles during counter-attacks, they manage to create more dangerous situations than a typical defensive scheme with 3 attackers in the rest offense. They are able to work as a team to maintain a higher and more compact shape while they press to force turnovers rather than cover deeper. They lure the opponent build-up forward and into more offensive positions to create a fitting transitional organization that they can attack with immediate passes into the channels due to the higher and wider positions of the depth runners. Firmino attracts the pressure from central players as he attacks through the middle, which further opens the wider channels for Salah and Mane to get open for passes and dribble at the defense.

Theoretical Background

So, from a more global point of view, there are very simple principles in positional attacks and in transitional ones such as the basic actions of protecting the ball, passing the ball, giving a passing option or reducing the oppositional cover that stays the same. There is one fundamental difference though: The opposition has to start defending from its offensive formation and intention, not from its defending one. Thus, the main benefit of so-called transitional attacks is that the attacking team does not have to de-organize the opposing defense as it is already disorganized. A basic example: passing with the highest speed possible without the pass getting intercepted is less risky and has a higher probability of success than from a more traditional attack in organized attacking and defending.

This simple premise, combined with a trend of teams defending better and better over the years, made the counterattack and transition play, in general, become even more important than it was before. Ralf Rangnick spoke on this topic in his piece on The Coaches’ Voice:

“Sometimes, teams park two buses in front of their box and force us to have lots of possession, which makes it more difficult to pick up pace and create clear goalscoring opportunities. If you have too much possession, your game resembles handball and you don’t get anywhere.

We are prepared to play risky passes, at the danger of them going astray, because that opens up the possibility to attack the second ball.

The most exciting thing for me is to see how the transition game has developed and accelerated. There’s so much happening in the eight to 10 seconds after the ball is won or lost. Those moments decide games, and a large part of our training is dedicated to what we call swarming behaviour; the synchronised movement of players.“

As it naturally happens with such trends, they define the next development: The organization in possession was not only developed to attack better, but also to defend better. Not only the decision-making regarding offering a passing option and passing changed but also the approach of coaches. Concepts like rest-defense evolved with differing rules.

First, the immediate prevention of a counter by counter-pressing emerged, coming naturally from the staggering when losing the possession of the ball and the risk a counter would give. Even tactical fouling or a changed attacking play in general (long balls under pressure or using higher risk in higher zones on purpose) could be factored into this category of prevention of the counter and an immediate shutdown of the transition. Its offensive purposes are very clear: There would be no need to change from attacking to defending while luring the opponents to do the opposite, ideally catching them on the wrong foot and being able to again attack from a (less clean) attacking organization with the opponent caught between two intentions and, thus, organizations.

Yet, teams would find a way out of these. In order to escape the press, rules of counter-press were mirrored and solutions created to solve these problems: Play the first pass out of pressure, ideally deep or diagonally, etc. “Rest-defense” as a concept stems from preventing these outlet passes going through the initial counter-press; “Rest-offense” or “rest-attack” is now another answer to this trend. By utilizing similar principles as in attacking play against a team having fewer players and organization behind the ball, there is the possibility of utilizing the typical advantages of the counter again, even when facing a better-prepared opposition – the combination with the prior defensive play and organization is the key in this regard.

Mostly players “gambling” for the counter would only be involved by covering a very small part of the pitch, preventing passes only near them and preparing for the transition that would (hopefully) ensue sooner than later. The next development – mainly utilized by Liverpool, but partly by other teams before – is a different involvement of the players positioned for the counter-attack; more activity when trying to win the ball or prevent specific passes, tied into the general strategy of the team for not only defending the oppositional attacks but also creating their own counters within their own attacking priorities.

Anything Else?

In the end, there is still more room to grow and evolve, and still more variations of counterattacks possible than the 3 general approaches to positioning and the 7 common patterns described in this article. On that note, it is important to remember that some of the details that were discovered through the 2010s from positional play can also be applied to the other phases of the game.

Jurgen Klopp’s Liverpool has brought football to another level over the last two years. Not only in tactics and strategy through the phases of the game, but also through recruitment and scouting of players, man-management, and analytics. It will be interesting to see how football continues to evolve as analysis becomes increasingly important in the sport.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Joan Oliva April 13, 2020 um 3:49 am

You are missing maybe the best way to start a counter in your 7… dribbling!! if you have space, take it! With teammates running into the outside corridors and defenders stucking in the half space… someone will need to comitt to leave the space or player.

…love the article btw 🙂

Emmanuel April 1, 2020 um 11:12 pm

Great article from Adin. Countless examples of this coming to fruition from Liverpool under Klopp exploiting the mutual interaction between ‘offensive’ and ‘defensive’ phases of the game