How to Messi

After the Argentineans’ poor start to the tournament, their minds are divided: Was Messi bad or was he badly involved? We analyze in detail which game-environment Messi needs to achieve his maximum effect.

This analysis was translated from the German article of Martin Rafelt.

Use the links in the German version for more information here: https://spielverlagerung.de/2018/06/22/how-to-messi/. The further analyses can be translated using DeepL.com.

One of the truisms of world football is that Lionel Messi works better at Barcelona than in the national team. It is cited as a prime example of how absolutely every player – even the very best – are ultimately dependent on their team. In view of the 2014 final, one could argue the other way around, but what is true in any case is that a player’s involvement determines his effectiveness.

Let us take a closer look at what Messi needs to be as effective as possible. What has made Barcelona such a good environment for him – and for many years? What is this mythical thing he lacks in the national team? And first: What things do you have to get out of one of the best and most complete players of all times to make it as effective as possible? Because the fact that he can do everything does not mean that he should do everything.

Playing the Defensive Structure

What Messi is often praised for: He is not only a goal scorer, not only a dribbler and not only highly qualified for the spectacular last pass. He also has the intelligence to be a full-fledged playmaker in midfield. He makes outstanding decisions and does not lose any balls. If he tried, he could probably be the successor of Xavi at Barcelona himself.

Why doesn’t he try? Because his other abilities are more extraordinary. Being press resistant with the ball in defensive midfield and distributing on the top level is not something many can do, but some can do it. Even if Messi could do it better, he probably can’t do it much better than his fellow players Busquets or Banega, for example, because these top players don’t leave so much room for improvement.

What makes Messi extraordinary, however, no one else can do. How often he splits a defense apart with dribbles, passes, and finishes are much, much better than anything else that others offer. Perhaps the closest to him in this respect are Eden Hazard and Mohammed Salah, and both are ultimately a class worse than him. Messi creates goals and he is most effective when he is put into the situation of being able to create a goal as often as possible.

You can Force Messi to Pass Back

But if you talk about his integration, you need another observation: You can force Messi to pass back. If you try to take the ball from him, he’ll probably just walk past you to the next higher zone. But if you do without it and just block this zone – at best in pairs – and also the other attacking stations, then Messi will normally not find an offensive option anymore.

This statement is important because theoretically, it could also be different. If you let Messi or Hazard play against a U17, then that would definitely no longer be the case. Then they could just walk past the opponents, no matter what they do. And then the involvement would really not matter. Because then they could simply walk forward from any zone, in any structure. At lower game levels there are players who are actually superior and play so far below their level. Messi plays below his level in professional football – but not that extreme.

Using Options vs. Creating Options

A useful model for offensive football is to distinguish whether a player or action only uses options that are already available (pass paths, open spaces), or whether it creates these options in the first place. Messi is an almost perfect genius when it comes to the first one. In the second, there are players who are better at this, but they are usually more inconsistent because they have to take more risk for this purpose and/or are not at this level in playing out the options.

Two good examples: Pelé and Ousmane Dembélé. Both have (had) an illogical dribbling style, which is much less clean than Messi’s. Dembélé is the more extreme example. While Messi has the ball always the same, always perfect and quickly controllable on the foot, Dembélé sometimes seems to bounce the ball, and it is often on the side or even behind his body and apparently not under control. This makes Dembélé less predictable, leading to opposing mistakes: Sometimes opponents take a step forward, but have misjudged and are played.

Pelé also often tried to get the opponents to react and force the breakthrough moment with many small feint-like ball contacts. This sometimes leads to ball losses and that’s why Messi actually does this. And that is one reason why it is all the more important for Messi to involve him properly; more important than for Dembélé.

Love Letters to the Right Halfspace

Messi usually finds the optimal set of options in the right offensive halfspace. Here he can dribble towards the goal, comes into shooting positions if successful and has various target areas well in view for the deadly pass on the way. Basically, it is enough to watch a Messi compilation to understand why the half space is such an advantageous zone for the attack.

Accordingly, Messi mainly plays in this zone and has almost always been used by his coaches in this position. His starting position didn’t really matter to him: In the end, he ends up in the same room anyway. The “position on paper” is only important for the positional environment. If he plays as a “false nine”, then the vertical line of the penalty area is occupied by the right wing (like Pedro), usually with a run from the outside to the inside. If he plays with a “real striker” (like Suarez) in the middle, the same room can be occupied from the center, which is more likely to provoke central defenders’ reactions than the opponent’s right-back.

In addition, the opponents orient themselves differently. With an aggressively pressing opponent, the right-back might put him under pressure if he plays nominally as a right-wing, the six would take him over if he plays as a #10, and a center-back might come out if he falls back from the center-back position. Messi’s base position induces opponent behavior and running options for his opponents. (#structuraldynamics) But for his actual playing position, it is almost irrelevant.

Nutcracker as Right Winger

However, Messi can also enter the wing zone from the right half space or as a right-wing outside. There he cannot create goal danger so directly and quickly, which is why the zone is not preferred by him. Although he played the position at the beginning of his career, it is in a sense the more progressive starting position for him: The difference is that it is much harder to defend a pass to him in this zone.

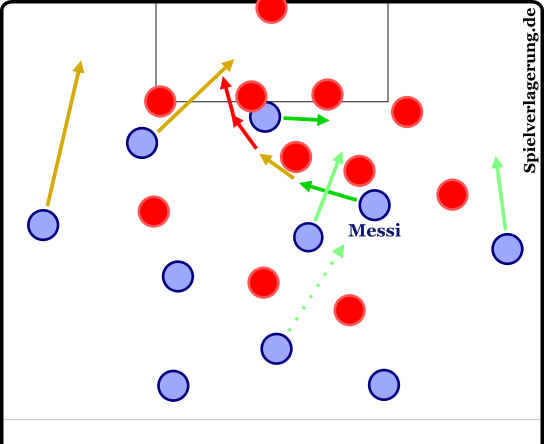

If the opponent wants to prevent a pass to Messi in half space, they compact themselves in half space; the famous “cage” around Messi. With a half space focus you open a bit of space, but overall the team is staggered well and can then press the wing shut or press into the middle. If an opponent defends compactly and cleanly enough, they can simply quantitatively prevent Messi’s actions in half space; simply by giving Messi the ball less often than normal.

Atlético, for example, did this quite well. What they failed to do was to prevent the passes to Messi if he fell lower and back to the wing. To prevent this, the wing would have to be defended extremely broadly before the ball is there. At the same time, however, the half space would have to be closed so that Messi wouldn’t just move inside or Messi’s teammates wouldn’t get through this gap. You would have to bring so many players to this site that the other ones would be completely exposed. Practically impossible.

And then Messi can’t immediately attack the dangerous penalty area zone, but he can dribble into his beloved half space and eventually have more situations there as a right-wing than if he were just waiting for the ball there. In addition, after such an action, the opponent is already moved further than at the starting point from the center. The notorious transfer balls on the ball-far Alba become more effective.

Pressing Killer in Deeper Zones

For another optional Messi position, the opponent’s behavior is a possible trigger. What is important about his normal position is that Messi can normally break through the opponent’s largest pressure zone there, and then runs against the rest of the defense at the perfect pace, in order to then execute it as cleanly as possible with the best possible follow-up options. Usually, the biggest pressure zone of an opponent is just there, centrally in front of the defense, especially when Messi is there.

However, if an opponent builds up a massive pressure zone further forward and Messi’s teammates are not able to get through there, then it is possible that he will not get any balls because the attacks are interrupted before they pass forward. Ideally, this should be prevented by the build-up players. But if this is not done, then it makes sense that Messi lets himself fall back deeper in order to break through this deeper pressure zone.

Typically, this is a good solution against consistent man coverage on the whole field. Messi can then simply get the ball with the opponent on his back, dribble past the opponent into space and thus turn the entire cover system of the opponent on its head.

In a very dense defense of the half-space and/or the center – let’s say in a 3-3-2-2-pressing – he could also fall back into a free space on the deep wing, on the outside defender position or shortly before it. From there, it could also fulfill the “nutcracker” function in vertical or diagonal form instead of horizontally from the high wing.

Falling Back into the Game makes Little Sense

But what seldom makes sense is Messi’s occasional falling back into a normal position outside the opponent’s block. He does this sometimes because it corresponds to the structural logic of the situation and then usually plays normal, logical relocation passes. He understands the game well and he probably likes it psychologically to get the ball if he is shielded too well for too long. But then exactly the described problem arises: You can force him to return pass. Its special, huge effect is lost.

In order to bring something special to these situations from these spaces, he would have to try to dribble at specific spaces in the opposing midfield line in order to force them to react. So smaller spaces could open, then play to them with other dribblers, move back to the front and perhaps force them to get the ball into dangerous positions in a dense block. He would then not wait for the ball but make the move himself, which would then lead to exactly the result he would like. If he could do this, he would be one step better and then really almost impossible to defend. Perhaps this is the only area in which he can still improve significantly.

Another variation would be that his falling back is a trigger for overloading vertically in front of him. For example, if middle and right wing strikers moved into this zone at that moment, their opponents would already have to make difficult decisions. Perhaps this would open rooms – on the right outside, half left or in the depth – which Messi could then play with passports or dribblings. Presumably, this has happened in some scenes, but I personally have not yet seen that this has been used purposefully.

A Question of Structural Dynamics and Attack Progression

These explanations make it clear that Messi’s effectiveness is based less on his starting position than on the overall interactions between the two systems. If Messi’s team finds ways to create enough pass options for the opponent to react and then break into emerging holes with good timing, Messi will find the right solution to connect the options.

It also helps if Messi is found at the right moment. If you play half right forever and Messi gets the ball, a lot of things are already closed. A direct vertical pass from the right central defender also usually makes follow-up action a little more difficult. However, if the attack is launched from the left and Messi is found on the far side after flat diagonal passes, the opponent’s position and orientation will be worse and Messi will often have sufficient options to get through quickly and clearly.

In general, it can be said that a better overall functionality of the team helps Messi. If the team is good without Messi, Messi is better when he comes in. If the team is an untuned, chaotic bunch, Messi will still clearly bring the team forward, but can’t be the same flawless scalpel that seems to take every opponent apart at will.

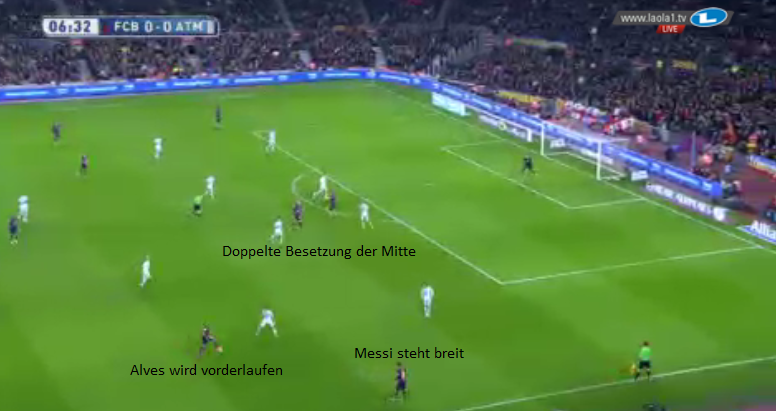

Support Player in Moment and Position

Messis effectiveness, when he comes into the right spaces, depends on the available options. Not to be underestimated is also the importance of his play stations for his dribblings: Especially against the central defenders, he dribbles successfully because they have to shield a perpendicular pass lane at the same time and thus at least a little open the dribbling route for him. As a right-winger against Atletico – and more generally in the season of Barcelona’s last Champions League victory – he was particularly effective, for example, because Dani Alves usually made a run through the half space and in this way pulled the dribbling path into the middle for him. Rakitic also does many such supporting runs.

The runs are also important for the final pass. Whether a run is for a pass or an opening in space depends on the reaction of the opponent, but because Messi is so good and because of tactical psychological aspects (footballers rarely do extreme things) it is usually the case that runs directed away from the goal create space for Messi and runs to the goal lead to the pass.

Inside Left Forward

A movement that falls equally into both patterns is the run of a striker away from the ball directly into the center of the penalty area (Henry, Villa, Neymar). This usually happens when Messi is central or slightly to the right. If Messi dribbles from right to left and the striker in front of him runs from left to right in front of the goal, the opponent basically can’t make the right decision.

If the opponents stop, both have an advantage in movement and can pass and dribble. When the inner defender jumps out on Messi and the outer defender stops, the striker is free. When the outer defender goes along, Messi dribbles into the emerging space.

The best solution would be for the outer defender to move out diagonally towards Messi and the inner defender to walk away from him and pick up the striker. Firstly, however, nobody does this because it is completely unusual in football for someone other than the closest player to attack the person with the ball. Secondly, the striker could also break off the run and simply get the ball in free space. This would still be easier to defend than the other two scenarios, but not optimal.

Wide Attacking Left Wing

Most likely it happens that both players just stop and somehow defend the passing lane at the level of the penalty area line and still can stand in Messi’s way. But then they are at least “frozen” in the position and oriented forwards to the middle.

Now the legendary Jordi Alba run is important. He can get a chipped ball from Messi like a dagger behind the defensive line. As the ball enters the half space, Messi can play it far forward without the goalkeeper being able to reach it – a perfect situation for the deadly pass.

It is also important in other situations that you have these two options when you are away from the ball. You bind players there and Messi always has two clear reference points in his field of vision and the entire width of the playing field becomes playable. If an opponent defends very broadly and can thus control Alba at the far ball wing, the half space is playable. When the opponent defends closely and controls the forward, the wing is playable. If both can be covered and the spaces around Messi are sufficiently tight, then certainly the return pass options are open and Messi’s team can easily keep the ball and prepare the next attack.

Space-Creating Half-Right Player

Rakitic’s role has already been mentioned, which is often taken over by Paulinho at the moment. An additional player half right, who is running and occupying the front, can pry open a very compact and close opponent. Not only can it open up space for Messi, but it is also the only way to get to Messi.

But such a player is not indispensable. Typically, it increases the pressure and therefore it brings more possibilities, a zero-sum game. If you play like Rakitic, Messi tends to have longer contact times with the ball and has to combine and dribble more until he arrives near the box. If you have a Xavi instead, which primarily holds the position behind Messi, then he should be able to play the ball between the lines. Then Messi will wait for the ball and has a little shorter contact times because he can start the actions closer to the goal. Positional play instead of dynamic play.

Optional: Dodging Center-Forward

A striker close to the ball, the Suarez role, is also an optional addition to Messi’s repertoire of playable options. If Messi has the ball, the striker can run into the interface in front of Messi and thus tie the central defender on this side. The main effect is that the two defenders who are away from the ball have an even harder time in the dribbling situation described above.

In addition, the striker can make sure that the opposing six wants to block the pass to him, making Messi’s dribbling easier. If the six doesn’t do that, Messi can alternatively combine with the striker or play him into the interface. In Suarez’s case, he’s very good at digging his way through the right-hand penalty area and finishing.

Pedro and Alexis Sanchez, for example, moved from a different position in a similar space in a different way. They tethered the opponent’s outer defender, prevented the central defender from moving out and were primarily sent behind when space was created behind the chain. With these two, the switch to Alves was a more formative means than with Suarez, because they typically opened up space there.

The Importance of the Right Back

Last but not least, the right-back is very important for the functionality of the team. In the long run, it is particularly important that it is versatile in order to be able to play different roles: That he can go inward and combine when Messi falls outward. That he can bomb to the baseline when the enemy moves into half space and the wing opens. And if he can then also return to the counter-pressing quickly enough, if the defense intercepts a ball, then it fits together quite well.

The defender is not so important for Messi’s actions, but there can be situations where the opponent strategically decides to leave him open in favor of a stronger guarding of Messi. In these situations, the defender should be able to cause sufficient danger; otherwise, the anti-Messi strategy becomes too easy and too effective. So, this is more game theory than structural tactics.

Sampaoli seems to have it on his Screen […?????]

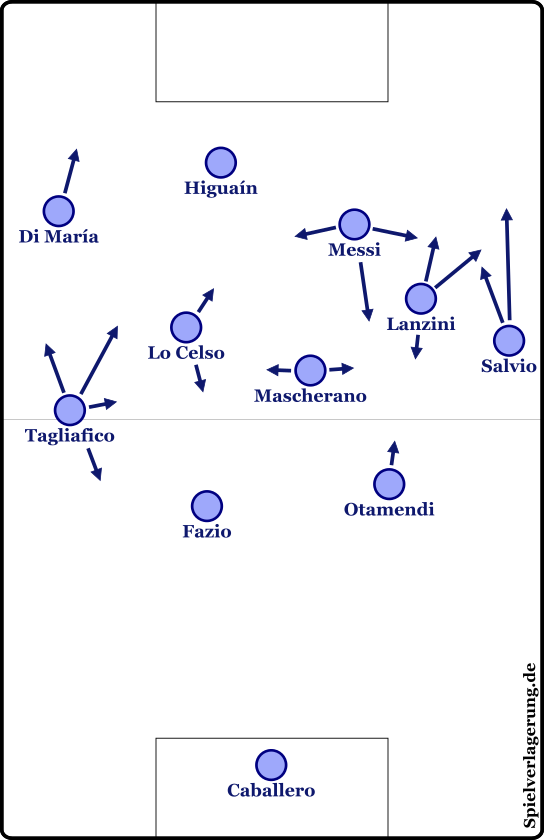

Argentina in the build-up before the World Cup in a test match against Haiti. This structure emerged from a 4-4-2 or 4-2-3-1.

Finally, recent impressions show that Sampaoli is aware of many of these aspects. The structure against Haiti had two solid pillars throughout the season: Di María, who occupied the distant wing – second – the far wing and thus the Alba role, as it were, as well as Higuain, who was primarily half-left and thus played the role of the incoming striker. The “optional” add-on players, on the other hand, were varied. Maybe Sampaoli will find a new, very effective structure there.

Addition with hindsight: Sampaoli was still oriented towards this system against Iceland and changed small things, and Lanzini’s injury was, of course, a problem. But that would have been enough for victory and two goals without a missed penalty. Then he knocked everything over and against Croatia only a handful of the players from the game mentioned above played. That didn’t work anymore. Croatia defended Messi excellently in the “cage” and Sampaoli didn’t get his top star into the game. Let’s see what happens against the deeper pressing Nigerians now…

AO’s in-depth tactical analysis of Argentina’s 3:0 loss to Croatia can be found here:

https://spielverlagerung.com/2018/06/23/how-did-croatia-beat-argentina-30/

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen