World Cup Preview: Mexico

We preview Mexico, North America’s top side lauded for their methodical attacking play and tactical flexibility under Juan Carlos Osorio.

Author’s Note: Some of the graphics feature players that were not called up to the final 23 man roster. As a result, omitted players relevant to the graphic will be referred to be their position if they featured in the scene. Some of the numbers worn by players in a graphic are not presently worn by that same player.

The Mexican national team appeared to have the next four years mapped out in 2014. After a controversial Round of 16 exit against the Netherlands, the enigmatic Miguel Herrera had guided the ship in a direction that Mexican fans were excited about. A bright future was ahead, as reflected in winning a gold medal at the London Olympics plus the U-17 side had put together two consecutive finals appearances at the U-17 World Cup. North American dominance was finally being clawed back by El Tri, as the United States team was unable to keep up with the new crop of Mexican players coming through.

The Herrera reign came to an abrupt end after news broke of him assaulting a journalist in an airport after the 2015 Gold Cup, leaving the federation back to square one to find somebody to lead the senior team. A series of interim, domestic managers handled the fixtures in the coming months, but an unlikely candidate rose up to take charge.

Enter Juan Carlos Osorio, a managerial maverick whose long-winding coaching career has taken him all over the world. Following a brief playing career in his home country of Colombia, he moved to the United States to study Exercise Science, with the vision of becoming a fitness coach for a professional team. His next stop in his vocational studies was Liverpool, where as a student at Liverpool John Moores University, he lived in a room of a house overlooking Melwood. An eager student of the game, Osorio meticulously scribed the training methods of Roy Evans and Gerard Houiller, which opened doors for him back in the United States, before moving to Manchester City in 2001 as an assistant coach.

Nearly ten years after beginning his head coaching career, Mexico decided to take a chance on Osorio, a hiring that raised eyebrows in the Mexican press. Even if he had developed a reputation for playing controlled, attacking football at his previous clubs, employing a foreigner for leading the senior national team was an unpopular move.

The Osorio era has been quite successful from a results point of view, with a couple of poor outlying results in major tournaments, most notably a 7-0 loss to Chile in Copa America Centenario. Even if Osorio has won almost two-thirds of his 48 total matches in charge thus, the Mexican public are not as optimistic about the likelihood of winning two of their three matches in Group F. However, thanks to measured play in possession, good squad depth, and tactically astute adjustments, Mexico have a fighting chance of upsetting the elite in Russia.

Overview & Squad

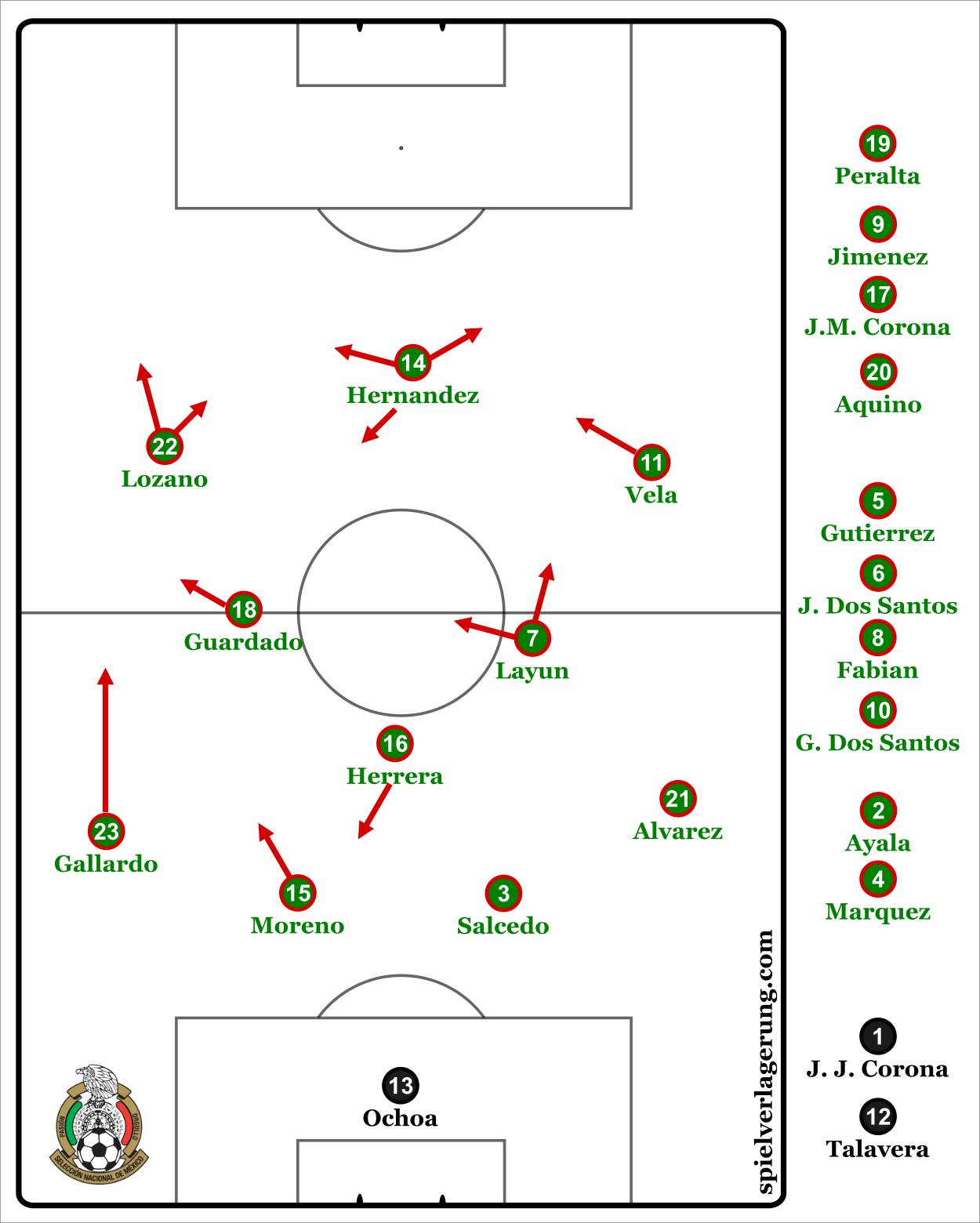

With most teams in international competition, the players that are most critical to the manager are the top fourteen or fifteen players, with the remaining players providing cover in case of injuries or suspension. With Osorio, every single player called up provides a tactical answer to a particular situation, choosing the options at his disposal with great care. In the group stage of the Confederations Cup alone, he used 22 of his 23 players, with only the third string goalie not making an appearance.

He also has never repeated a starting XI throughout his entire spell as manager of El Tri. There aren’t any overwhelming star players that are guaranteed a spot in the starting XI. The players who come closest to earning this title are Hector Herrera, captain Andres Guardado, and Hector Moreno. Despite their strong performance, Osorio will not hesitate to drop them if their inclusion does not provide the best tactical solution. These constant adjustments to his team make Mexico wildly unpredictable to plan against, and also frustrate fans who subscribe to a “do not fix what is not broken” mantra.

From a previewing perspective, we can only claim a handful of things. Throughout Osorio’s reign, an orthodox 4-3-3 has been the customary structure of choice. In other matches, particularly those where they anticipate dominating the bulk of possession and scoring opportunities, Mexico have also dabbled in a variety of structures that comprise of three at the back such as a 3-4-3 with a flat midfield and one with a central diamond. In these situations, a myriad of different structures, usage of players, and player movements have been seen. One match differs from the other in terms of the personnel used and their function. Osorio makes numerous adjustments over the course of one game, some of which puzzle the normal fan at times. Just one example of this in action took place last June against the United States, where the Colombian manager made four seismic changes over the course of the match in search of a winner.

Tactically, Mexico are very difficult to predict. Strategically however, they will always aim to establish control of the centre through their possession, penetrating according to the personnel on the pitch and the weaknesses of the opponent. Their wings function to as a means of creating isolated situations for their skillful dribblers, and also creating overloads to open spaces elsewhere on the pitch. It is these factors, alongside their exciting and adaptable squad, that render Mexico to be one of the most fascinating teams in international football.

https://twitter.com/EduardVSchmidt/status/1000902607861411841

Build Up and Areas of Emphasis

In Osorio’s prior jobs, his team’s play in possession was consistently among the high points of his tenure. Given Mexico’s dominance in CONCACAF, a manager competent in possession is definitely helpful when it comes to breaking down teams aiming to stifle and frustrate attackers. El Tri are flexible in attack, able to play through pressure at a high tempo, patiently probe and circulate in search of open spaces, or knock it long and play a direct game based off knockdowns. The style implemented is heavily dependent on the players, as each player selected is a piece of the tactical puzzle.

Positional Principles

Mexico are frequently adjusted from match to match, but there are some notable consistencies about how they are organized in possession. First, irrespective of the formation, there are always three defenders that provide cover if any mistakes and losses of possession take place. When using four defenders, one fullback will play higher up the pitch as a winger with the other staying more central and being conservative with their positioning. Most commonly, the more advanced fullback is on the left side and the cautious one plays on the right. In Russia, the advanced player will either be Miguel Layun or Jesus Gallardo. Carlos Salcedo, traditionally a centre back, has feature as a right sided fullback for many matches during Osorio’s tenure. With Diego Reyes now out due to injury, he could be moved centrally as Edson Alvarez takes the right fullback spot.

With three at the back, sidebacks will step gradually from the central pivot, but nothing too far that disrupts the three player cover. The wingbacks traditionally provide the width, permitting more attackers to move centrally. No matter what, the vertical zones of the pitch are occupied in possession, with wingers/fullbacks likely occupying the wingers, the no. 8’s in the halfspaces, with the remaining players moving in and out of the centre as they see fit.

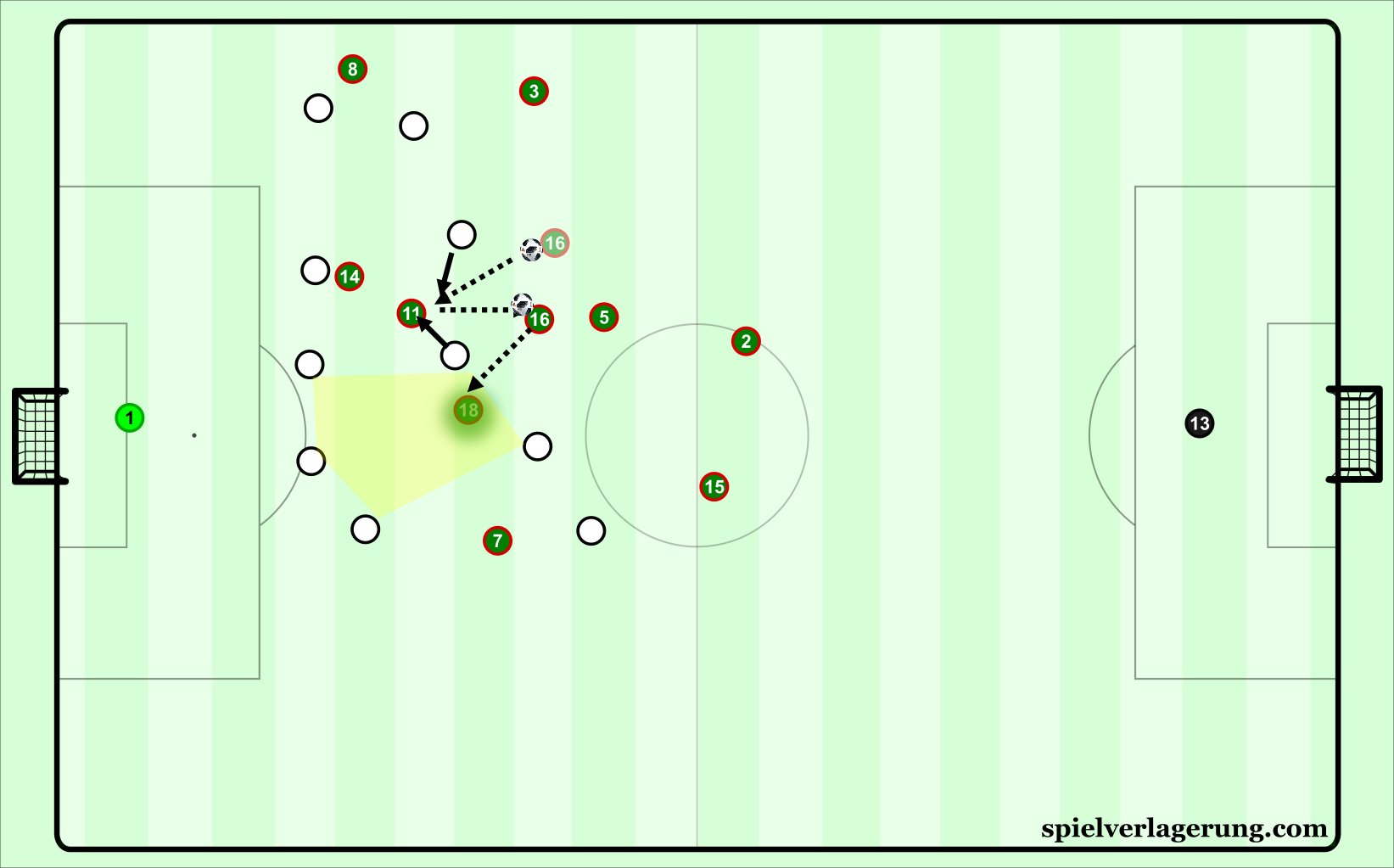

Lastly, Mexico’s positional possession governs how their players space themselves. For instance, they rarely exceed more than three players on a horizontal line in possession for staggering purposes, as shown in the inkscapes above. Due to the asymmetry of Mexico’s structures, four players in a line appears occasionally. This is more as a starting point in possession and does not appear as frequently within the dynamics during a match. Mexico are smart about the angles they provide as well, offering themselves diagonally in relation to nearby players and rarely offering anything in a straight line from the ball carrier. Having players staggered in such a way leads to easy triangulation in possession for circulation, more area for the opposition to cover zonally, and provides supporting players for layoffs and knockdowns, benefits that will be expanded later. These guiding principles of Mexico’s attack lead to numerous structural possibilities in attack for El Tri.

Constructing Attacks

Usage of Halfspaces

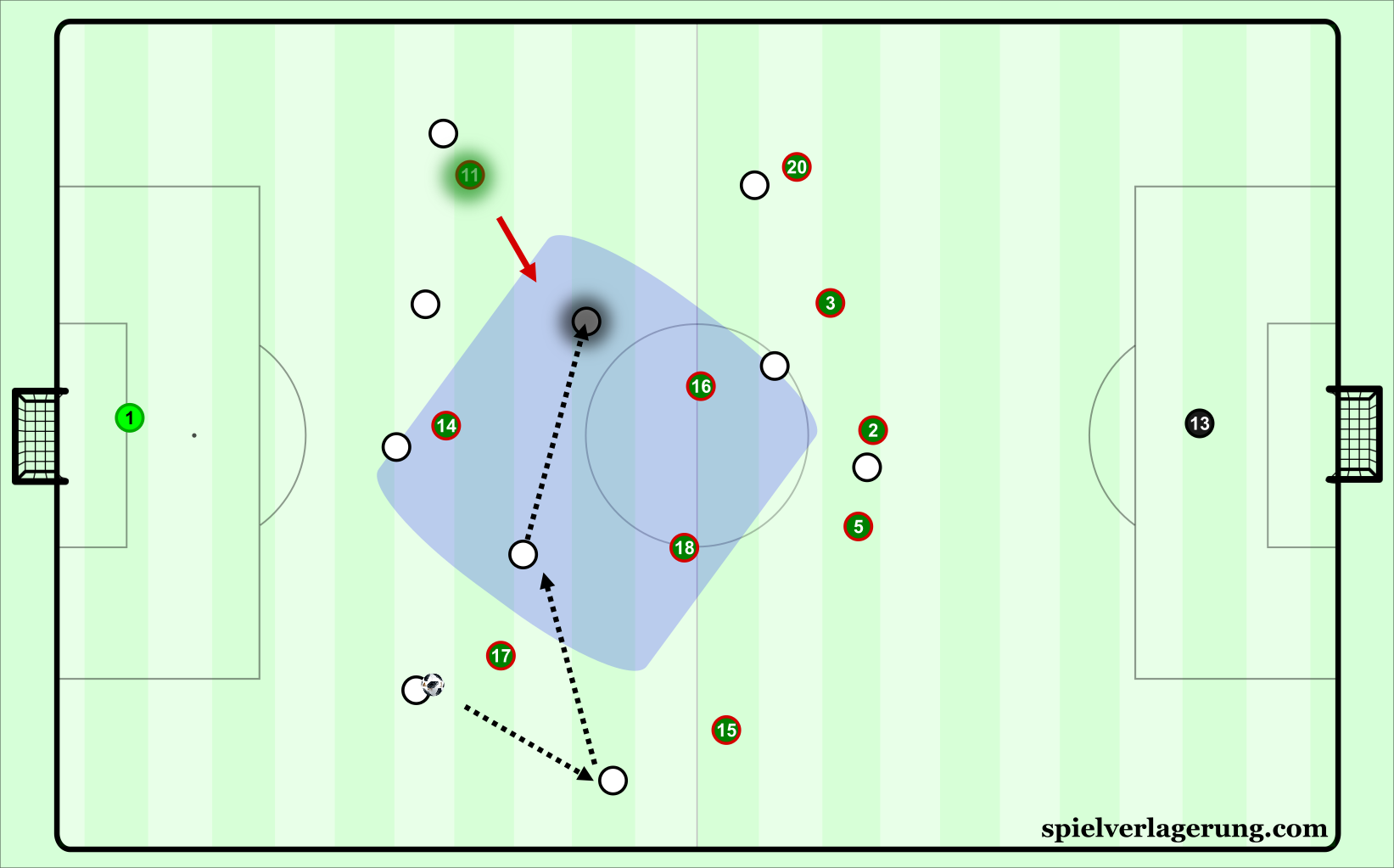

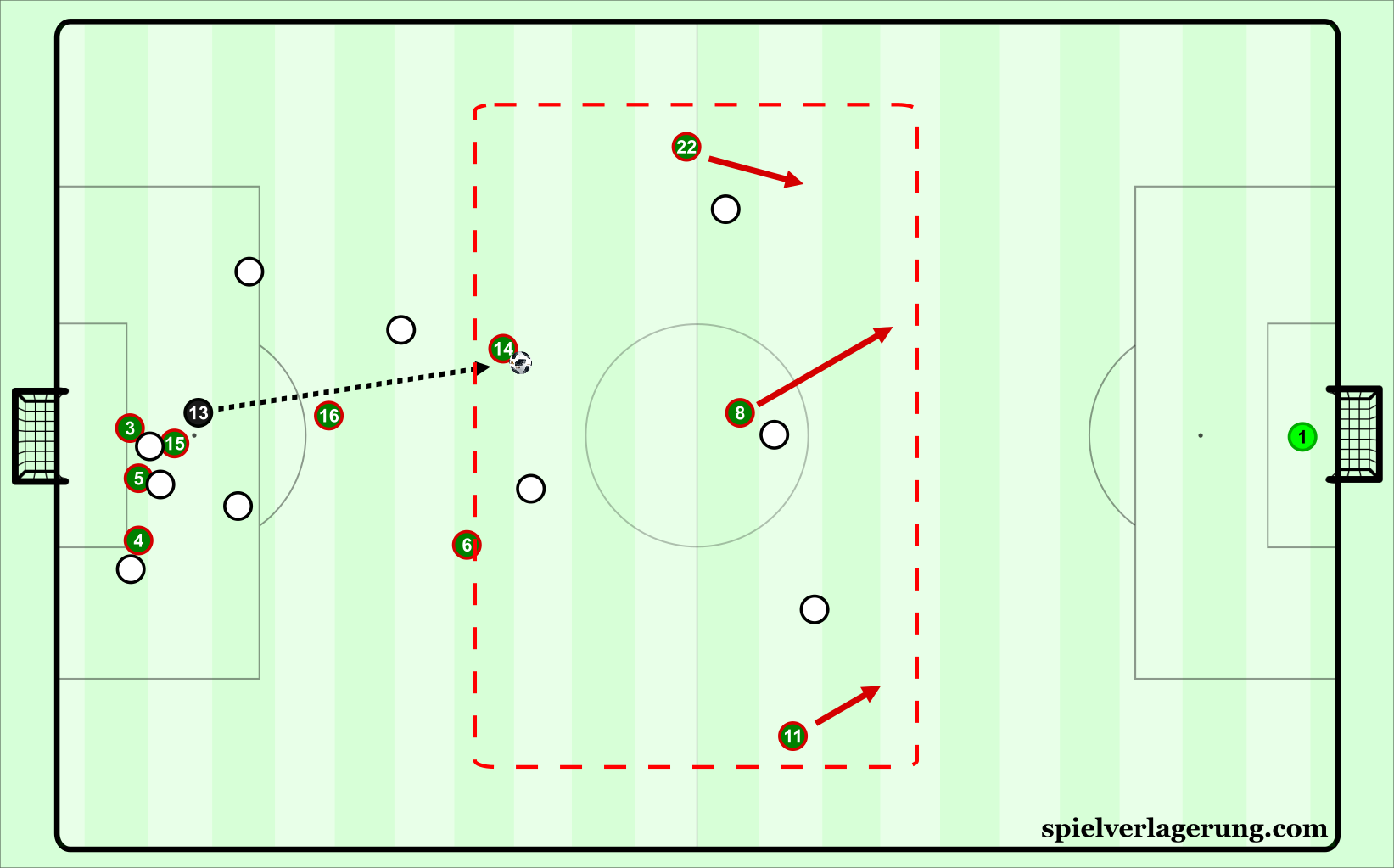

In the midst of their constructive possession, Mexico aim to play shorter passes to establish themselves in opposition territory for teams that drop off, or to pass around their opponent’s pressure. The centre backs will start wider from goal kicks, and gradually pinch in as they move forwards. The holding midfielder, most frequently Hector Herrera, places himself just in front of the centre backs. This player will occasionally drop into the defensive line to open up passing lanes for players in front of him and provide an additional supporting option.

When the space is available, the centre backs for Mexico have no hesitations about dribbling forward into it. Not only does this push the team closer to goal, but by the time an opponent moves to pressure the ball carrier, another passing option will open up as that player leaves his man, creating a free player. Once he moves up and plays to the free guy, the receiver can take space or move the ball to the next player.

This action is critical toward Mexico’s consolidation of possession and helps open up spaces for their attackers higher up the pitch as the defense responds to the new position of the ball and the available passing options.During these moments, the holding midfielder will drop back slightly if there is only one other centre back in the structure. This not only opens up a passing option if there are no quality options forwards, but also provides an additional player behind in case possession is lost during the dribble.

Further up the pitch, the 8’s have quite high starting positions, located in their respective halfspaces around twenty metres from the no. 6, similar to Peter Bosz’s Ajax and Dortmund from the last two seasons. There is little interchange between the two of them horizontally, moving up and down vertically in their respective halfspace. By staying higher, opponents wanting to cover them must retreat deeper to minimize the space if they do not wish to pressure Mexico’s defenders. This causes them to defend closer to their goal since few of Mexico’s opponents have engaged their defenders. Having their opponents closer to goal thus creates spaces for El Tri to build up in the opposition’s half and limit goal scoring chances for the opponent.

Having these midfielders higher also boosts the speed of play and effectiveness of their diagonal passing and lay-offs. Nearby defenders gravitate toward the ball as it travels to one of the central players, opening up lanes for other players nearby. When the receiver bounces the ball back to say, the holding midfielder, another forward option will be open thanks to the previous collapsing of the ball. This could be the other higher midfielder, the centre forward, or a winger. Yet thanks to their initial starting positions in reference to each other, they circulate the ball fast and move to goal when the spaces are open. Mexico patiently probe their opponents looking for this collapsing, hoping to find the right option with the best situation to go forward, whether that be through the dribble, combination play, or providing a cross into the penalty area.

As Herrera plays into Vela’s feet, the opponents close in toward him, opening up space for Herrera to pass to Guardado once he receives the ball.

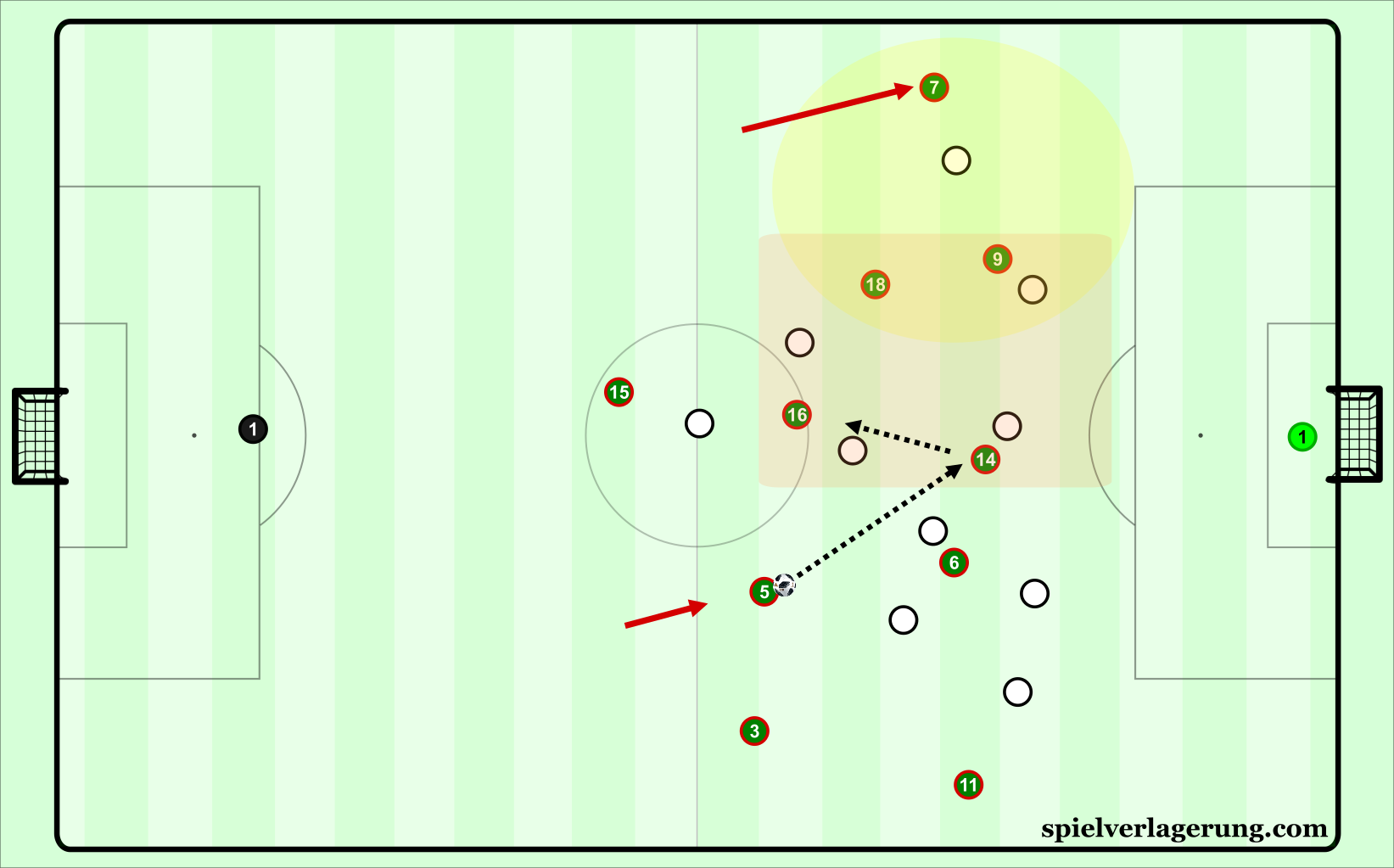

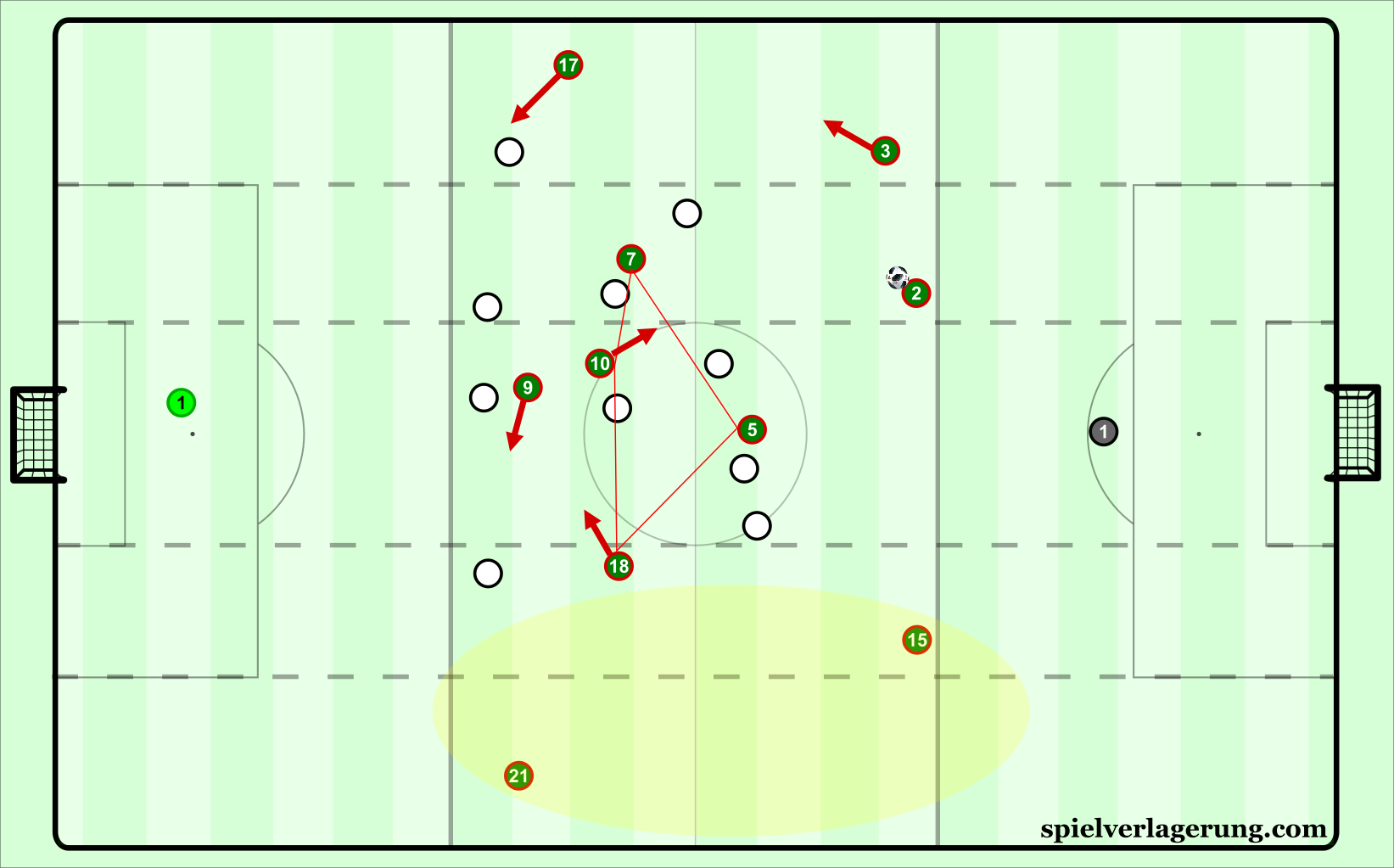

Lastly with the forward line, the wide players start along the touchline. Once a fullback advances to occupy the wing, the wide player on that respective side drifts inward toward the centre. With the left fullback usually being the more attacking minded player, the leftward man most often goes in the halfspace to act as an attacking midfielder just in front of the centre forward. This action has worked in creating overloads in both the centre of the park and the left wing area.

Four players are now central. If a wide player moves inside, this coerces the player in this zone to make a decision about whether to follow him or pass him along to a player in the area where the player is moving. Consequently, if he does not follow him, he can move into space untracked or force a nearby player to account for two or more players. Considering the left is frequently Mexico’s preferred side for build-up, this creates an overload on that side and facilitates quick progression into the attacking third. When playing through the right, this dynamic enables combination play centrally to find other open options and begin attacking the opposition.

With the ball on the right side, Mexico’s left halfspace overload gives ample chances for attack. After Hernandez lays it off to Herrera, they have a numbers advantage out wide but elects to pass to his right.

Issues and Adjustments

An issue found with the 8’s is that they are covered out of the match by opponents who are strong with high pressing as a team, rather than a handful of players. Against Germany in the 2017 Confederations Cup Semi-Final, both centre backs struggled to deal with the German pressure from Timo Werner and the three players behind him. By applying pressure to the ball whenever possible and compacting the field through fast shifting, Mexico struggled to find the 8’s. This issue was twofold, as not only were the midfielders not fast enough to respond to the German press, but the centre backs were not resistant enough to the pressure of Werner to be able to cope with the intensity. Nestor Araujo, who particularly struggled that match, will not be making the trip to Russia due to an injury suffered in training.

The large distances between the 8’s and the defense also increased the difficulty of entry passes into midfield. At times, the centre backs would elect to not play passes into desirable locations simply because the risk of the pass was too high. If the pass was intercepted, the opponent could counterattack easily given Mexico’s expansive shape in possession. To prevent this from happening at a high rate, Guardado began occupying a closer position to the midfield pivot, at times becoming the deepest guy himself. This will be touched upon more in the defensive transition section of this preview, but Guardado is the most important player strategically for Osorio as he provides a balance structurally that nobody else can replicate adequately.

Another distance issue occurred most frequently when Giovanni Dos Santos was included in the team. The LA Galaxy man would check too deep and not pose any sort of danger out of possession to the opponents. Because of a lack of presence in forward lines of the team, Mexico would end up having more defensive possession as fewer options existed forwards. Defensive possession is fine if the team is multiple goals ahead, but not ideal for circumstances where the opposition are playing a deeper block and the team needs a goal. When Giovanni moves in such a manner, he reduces the distance of any pass that goes into his feet. The passes do end up being very low risk, but don’t accomplish anything when it comes to actually shifting the opponent.

Osorio has presumably recognized these issues and adjusted them accordingly. In his team selection, he no longer places two similar midfielders in the same team. Jonathan Dos Santos and Marco Fabian will likely not play at the same time, because of the common issues they each face in possession and the subsequent transition factors that come from their positioning. Miguel Layun has been also been enlisted centrally in friendlies, performing very well at times, opening the possibility of him entering the midfield in the competition. Layun generally remains deeper, and the other midfielder moves into advanced space. With Guardado in the team, Layun actually became the highest up of them all, showcasing himself nicely there without the same relentless attacking charge of a Dos Santos brother. By having this personnel balance, it also solves the case of the distances between midfielders. No longer does Dos Santos need to check deeper to receive the ball, since there is a player in between him and the holding midfielder to ease the distance.

With the most advanced midfielder, the speed of recognizing when the centre forward checks into midfield has improved greatly. To avoid a vacuum in the area where the striker was, the closest midfielder will up into the space to maintain the structural integrity of the group. An overload centrally is briefly created as the fourth player arrives in midfield if the centre back does not step up. If the centre back does move with the forward and leaves space, the highest midfielder interchanges with the forward and slots into his space. If moving into that area is too far, then a winger will pinch inside and the centre midfield will tread toward the wing.

As Jimenez checks in, Giovanni clears the space for him by moving into the next line, rather than drop deeper as he did previously. Lozano tucks in to take Jimenez’ spot and occupy the centre striker area.

Entering the tournament, Mexico’s predominant issues revolved some of the profile in midfield and the interactions between them have improved. The main questions surrounding this group will be if they are able to replicate the dominance of possession that they had in CONCACAF play against superior opponents. Recent matches suggest that they will be able to manage the game effectively, meaning that their positional play may surprise the top teams in the tournament.

Chance Creation

Switching of play and Wing usage

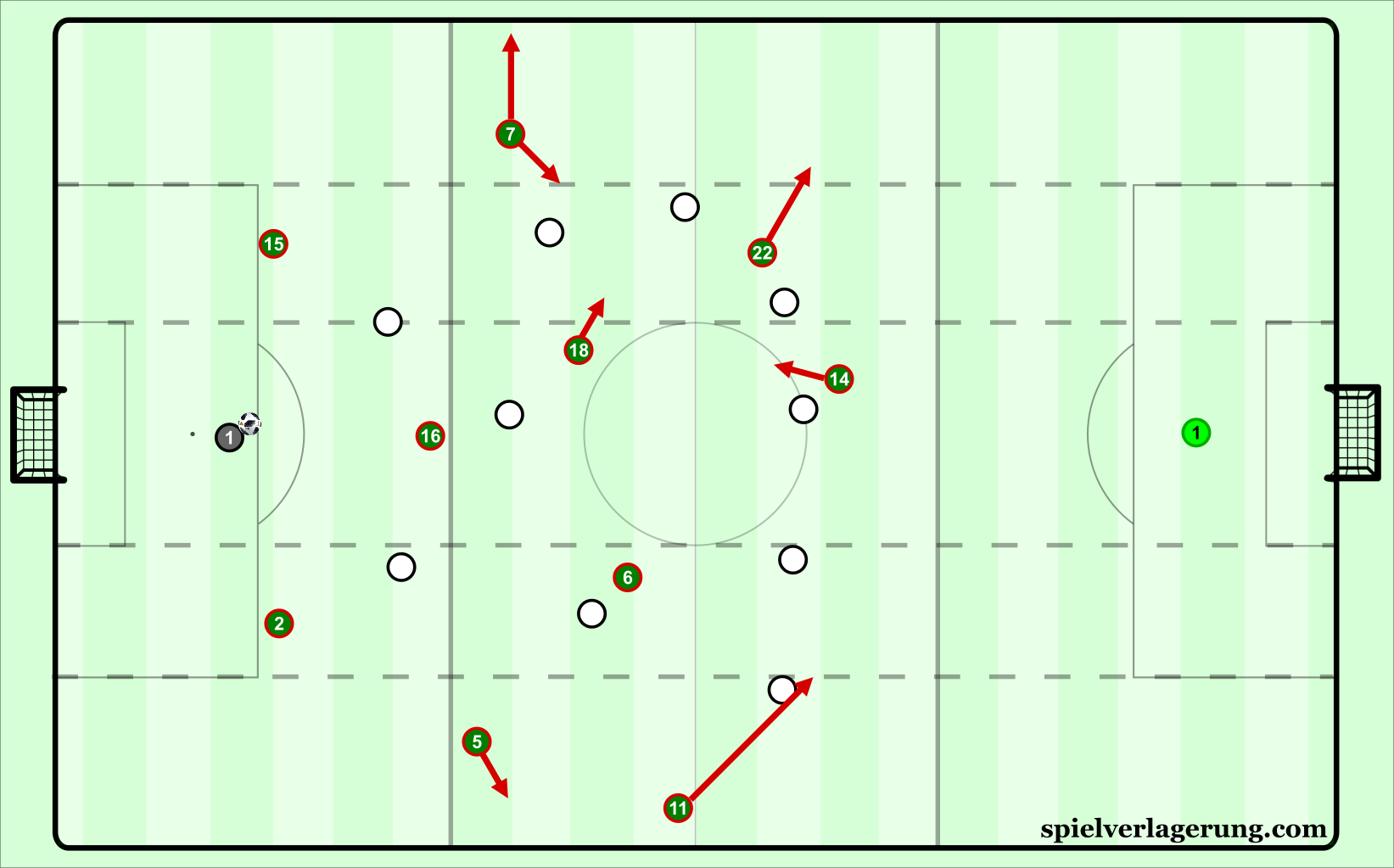

These circumstances where Mexico overload the halfspaces have been hard to contain for opponent. This is in part due to Mexico’s strong wing play as well. More will be discussed about the dribbling components of it, but with a strong trio on the left side (most often Layun, Guardado, and Lozano/Aquino), they maneuver down the flank thanks to strong combination play and the angles of support that they provide for each other. On the right side, this collaboration is seen less frequently because of the conservativism of the fullback, alongside Vela’s propensity to move toward the middle. Osorio has adjusted the team in order to replicate these actions on the right, but these forays have been less successful.

Thanks to the occupation of every zone in the flow of play, Mexico are able to effectively switch the point of attack and head to goal in a variety of ways, taking advantage of their opponents shifting too far toward the ball if they aim to shrink the playable space. The main methods used to switch the ball are either a long flighted diagonal pass across the width of the pitch or having the far side fullback step up and join the attack late, leaving him with plenty of space to dribble in and create a beneficial situation.

With the long diagonal, it is mainly used when the opponent has successfully covered the nearby passes in the early stages of buildup. The main perpetrators of these passes are the centre backs, with Hector Moreno in particular playing the bulk of them. Rather than play them to deal with pressure, these balls are targeted toward players that have successfully isolated their opponent and have space to dribble past them and progress forward. Given the speed of Vela, Lozano, Aquino and co, giving them room to play with is not a good proposition for many teams. As a majority of the team focuses themselves around the ball, the far side acts as a haven in case the opponent either covers everything nearby and/or overcommits. With one of them remaining wide, they are able to get forward quickly if the pass is on target.

The other way Mexico alter the point of attack is through a sorts of sideways possession. When playing through the centre to switch the sides, the far side fullback will remain deeper in order to be the final recipient of a series of horizontal circulation. If the opponent was heavily ball-oriented, the fullback will be able to dribble forward to take space and gain territory towards goal. In the instance of a winger remaining wide as well upon reception, Mexico will aim to progress through wing combinations targeting the isolated opposition fullback. With late support from central midfielders, this can create some of Mexico’s most intricate play and massive contributes to their chance creation efforts.

Two ways Mexico switch the ball. One through long aerial diagonal passes, the other through horizontal circulation through midfield.

In addition to the usage of width for circulation, Mexico’s skillful wing dribblers are vital to their chance creation as a force of destabilizing opponents. Hirving Lozano and Javier Aquino each are quite linear with their dribbling, hoping to move down the line with the view of playing crosses from the byline. Each of them can play on either side effectively, but are placed on the left side more often since Vela is preferred on the right. Lozano will cut inside more often, looking to slip forwards in behind with through passes. Regardless, both of them are remarkably skilled at protecting the ball and dribbling past their opponents. They can thank their diminutive statures for the functional benefits of a low centre of gravity and agility as they slalom around defenders.

Carlos Vela uses the wing slightly differently than his compatriots. A left footed player on the right side, he aims to dribble centrally to unlock passing lanes that were unattainable from the wing. Arjen Robben-esque at times, the frequency at which he attempts these inside dribbles can be overwhelming, leading to teams being able to predict it quite easily. Vela however comprehends the right moments to dribble versus pass, dribbling when he is isolated, and passing when he has adequate adjacent to him. The dynamic he brings is quite unique and no other player in the Mexican team can mirror it. The diagonal nature of his movement, dribbling, and passing complements nicely the linear focus on the left side, therefore adding yet another sense of multidimensionality to El Tri’s Attack.

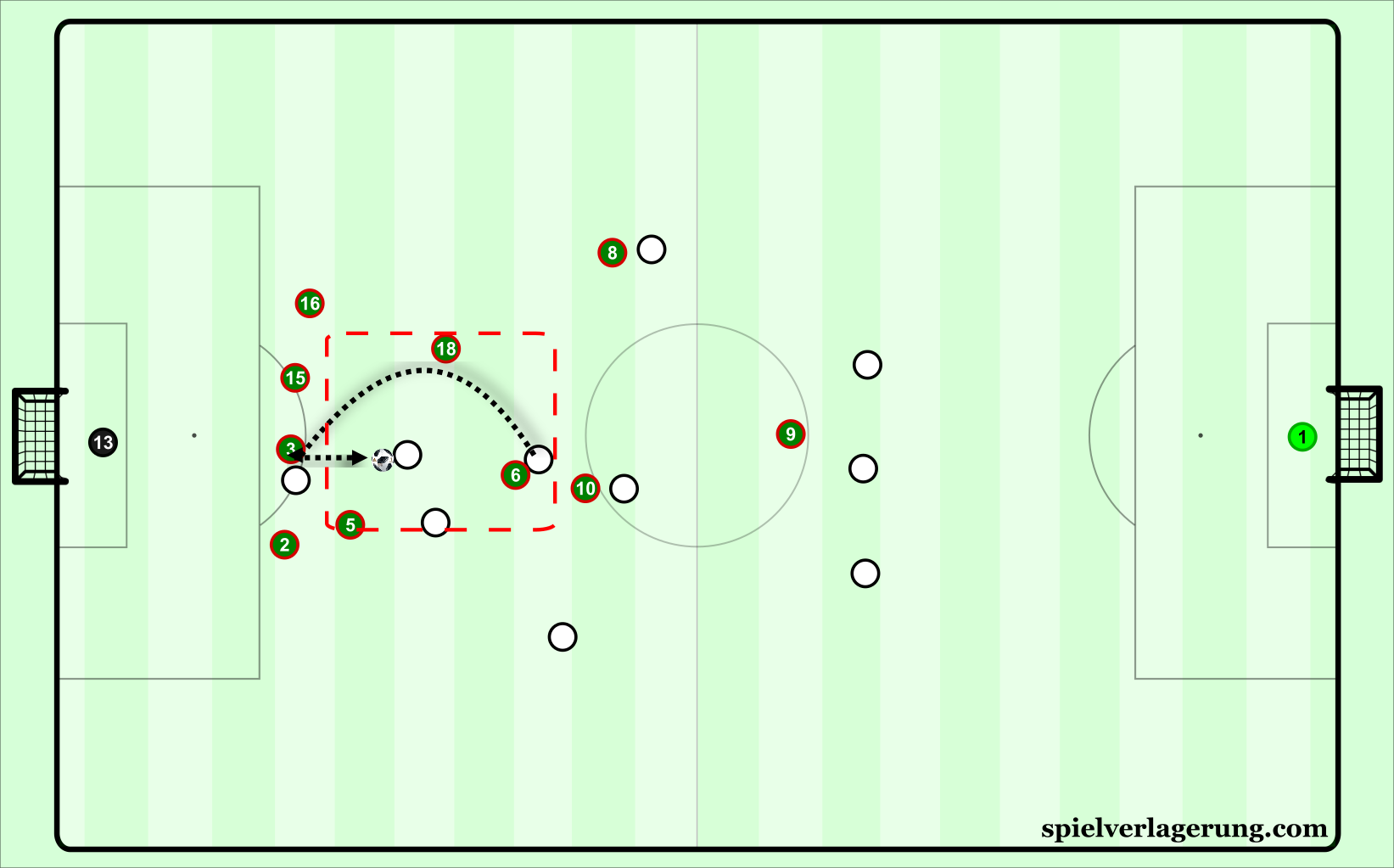

Attacking the Box

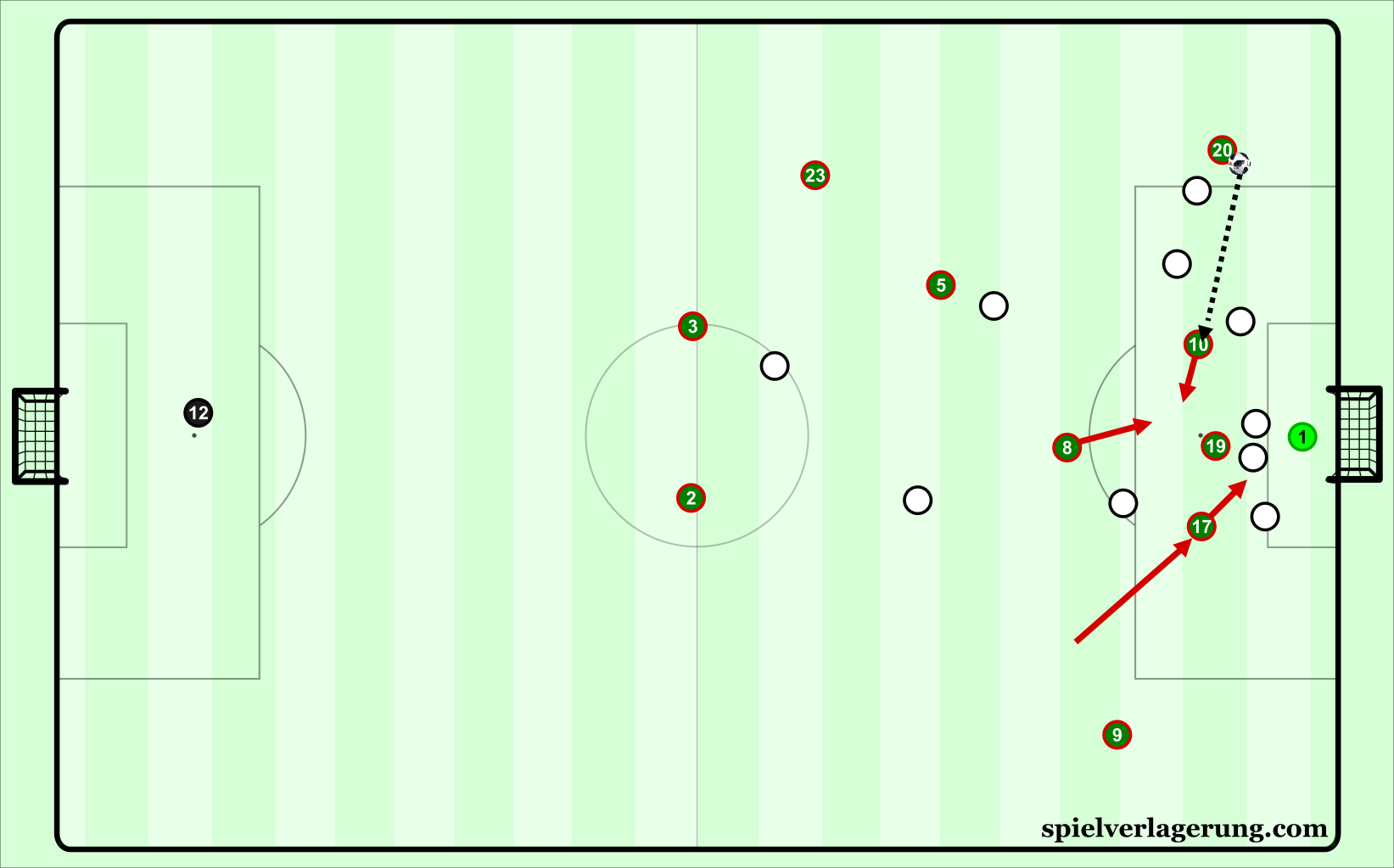

Once the ball is in wide areas in the attacking third, Mexico’s front three plus the centre midfielders when are strong examples of both getting numbers into the penalty area and timing their runs in relation to the placement of the incoming ball. If the ball is with a wide forward, the other one darts centrally either to get on the end of a cutback, or to get on the goal side of the marking fullback. The centre striker predominately uses the penalty spot as his frame of reference, moving toward it and simultaneously adjusting his orientation so that he faces both the goal and the incoming pass.

Approximately five meters from the top of the penalty area, a centre midfielder will creep up slightly and increase the intensity of the run in order to gather momentum if he strikes the ball off of a cutback. If available, his partner will even join in, getting as many as four runners into the penalty area. The cutbacks are particularly effective as when the ball is that close to goal, the opposing defense will be preoccupied with protecting the goal at all costs, subsequently dropping just in front of the goalkeeper. Midfielders either will drop into line with the defenders to help out, or be too far from the play to be able to contribute.

This leaves a sweet spot just at the top of the penalty area that is often neglected by teams defending wide areas. Osorio’s Mexico has focused on these areas for the creation of goal scoring opportunities, even using their tendency of playing cutbacks as a decoy to play options closer to goal as defenders cheat up in anticipation. It is through numerous penalty spot occupation, selfless individualism with wing dribbles, and a keen notion of timing that the fairly short Mexican side is strong in chance creation from wide areas.

Form Fits Function – How Selection Dictates Chance Creation Approach

The front three can take a series of combinations thanks to the number of options and the versatility of each of them. Lozano and Aquino provide industrious efforts in attack headlined by their previously mentioned dribbling capabilities. Jesus Manuel Corona, also known as Tecatito, brings a mixture of Lozano’s crafty dribbling and proficiency in combination play. He is adept in featuring out wide, alongside more central areas to play off the centre forward if needed. Carlos Vela effectively functions as an inside forward, but has been slotted as a central midfielder at points with rare spells at centre forward.

The options at centre forward are equally flexible and adaptable. Javier Hernandez enters the tournament as the nation’s all-time leading goalscorer, with fantastic spatial ability both in buildup and in the penalty area. He tends to be at the right place at the right time and can move around the front three within the flow of the play. Raul Jimenez of Benfica is the preferred target man of Osorio, providing a more direct option for teams that play with higher lines and those that struggle with long balls. His play style and impact on this Mexico team is reminiscent of Mario Mandzukic, blending strong aerial play with a selfless team contribution in all phases of play. Jimenez also occupies the focus of opposition defenses nicely because of his movement and aerial ability, hence affording more space to play for his fellow attackers. Lastly, seasoned Oribe Peralta adds another strong physical presence, providing a hybrid between the timing of Chicharito and the physique of Jimenez.

Like a chef designing a recipe, Osorio aims to combine all of these differing abilities that each player brings to create the optimal mix for the given opponent. Mostly every player in this front of the team can play all across the front line, giving Osorio several combinations when it comes to his personnel.

Defense

Pressing

Mexico’s pressing can appear in a variety of ways relative to the objectives of the match. When playing more direct teams, the forwards will invite passes into the defenders before sprinting at them to force them to air it out quickly, potentially compromising the quality of the pass or deflecting the pass and possibly having the ricochet fall into their path. They will do similar against teams with weaker defenders in possession that are more possession-oriented in their attack development, aiming to provoke mistakes rather than just execution errors.

Behind them, Mexico set an offside line far from their own goal, showcasing their intent to recover possession either with the goalkeeper or through recovering possession in their attacking half to drive to goal quickly. The compactness between lines is satisfactory, sometimes distances between players is a little high which exposes the halfspaces to penetrate. Overall, the distance from front to back is solid and not one of the principle concerns.

There are some weak points in their pressing that make it quite ineffective against top teams. When playing an nontraditional variant of a formation, say with a narrow winger at all times rather than a wider starting position, there are some problems regarding their access to the wings. For all the attacking ability that Mexico possesses, the front players do not have that same aptitude on the defensive side of things. They either will remain too narrow and not be able to close down effectively in the wing, or vice versa and leave important spaces open centrally.

Once stretched out by the initial passes, Mexico are left sort of scrambling while trying to reclaim territory. However, this tasks becomes much harder without adequate help from the far side. Suppose the ball is on the right side: for claiming a better foothold of the centre, the left sided winger will tuck in centrally at least so he has access to pressuring the center when a pass is targeted near him. This doesn’t happen at a high enough frequency for the Mexicans. Instead, players near the ball end up having to do more chasing rather than the teammates surrounding them making pressing easier. It’s an inefficiency that comes with their play.

Corona lacks any intensity with his pressure here, permitting the opponents to easily find the next pass. Because of the lack of far side help from Vela and Chicharito, the play can easily be switched thanks to a large exposed area in the centre.

Considering Mexican teams do not frequently pressure high in the manner that Osorio asks them to, partially due to the strong heat of the nation, partially because of more focus on play in possession, he can only develop them so much over time in this respect. Possession not only acts as Mexico’s source of constructing their attacks, but also acts as a safeguard against having to press teams with sophisticated attacking dynamics and press resistant players.

Pressuring the ball when matched up only does so much at the top levels. Mexico’s pressing schemes more often than not are strategically correct, there is just a gap in terms of implementation when faced against superior opposition that could be a decisive factor in whether they make a run or get knocked out.

Defending Long balls

Another issue that the Mexican side has faced throughout the run up to the tournament is defending long balls, particularly when it is used as a mechanism of beating Mexico’s high pressure. Considering much of the team is shorter in stature, a more aerial and direct way of play would understandably annoy them and lead to struggles. Even their taller players, Moreno, Ayala, and Rafa Marquez are relatively short relative among centre backs at six feet tall.

Mexico actually do a decent job of competing in aerial balls off of situations such as goal kicks and set pieces due to strong organization, but this tends to disappear in open play. It’s not exactly the headers themselves that threaten Mexico, but rather the sequences following the long ball and the inability to deal with second balls. With Sweden being one of the most physical and direct teams in the tournament, this area of focus is vital.

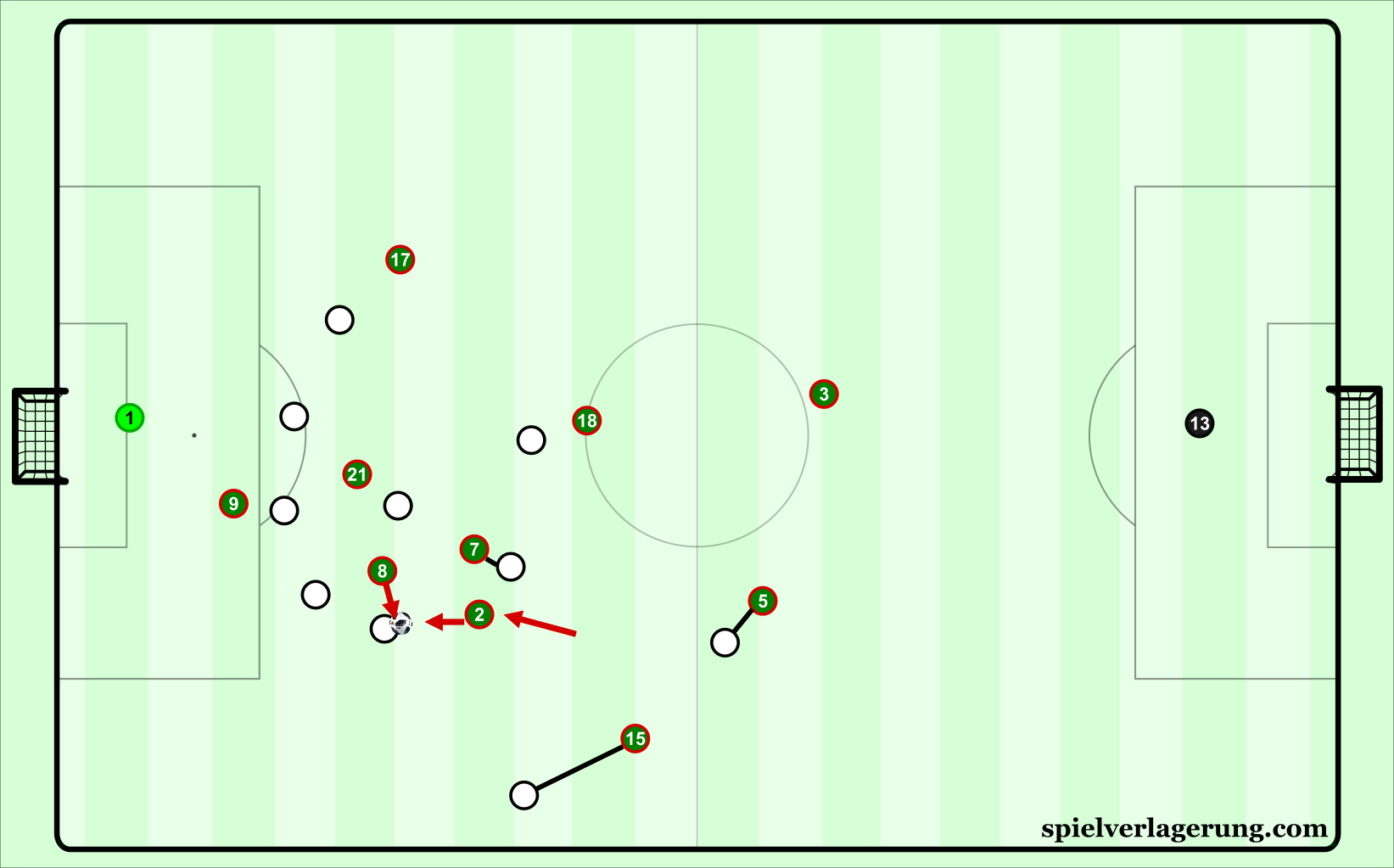

For the disarray surrounding second balls, it boils down to a series of things surrounding the qualities of the players and local occupation issues once the long ball is played. In open play, opposing strikers will have more space around them and are able to use their bodies to help with pushing off of centre backs. From there, they can knock the ball down, or at least disrupt the player going up with him to prevent headed clearances. The higher positioning of Mexico’s 8’s leaves Herrera having to cover a lot of space individually, meaning he is more prone to getting ball-oriented on these long balls as a coping mechanism for all the space. If the second ball is out of Herrera’s reach, then Mexico often have issues.

Once the ball is toward Salcedo, his failed clearance is almost punished because of Mexico’s poor occupation of the middle to challenge second balls.

Some of Mexico’s midfielders have little interest in helping in this phase of defense. They sometimes literally watch the ball go in the air and let opponents run past them. Others make an attempt to provide help, but just lack the tenacity to be able to restrain more physically imposing players in these kind of matches. They don’t have to outmuscle their opponents and dominate the area. The main requirement is to keep them at bay. Moving Miguel Layun into central midfield could be huge in solving this, as other midfielders like Marco Fabian and Jonathan Dos Santos are not as able defensively.

Mexico’s chances of advancing out of Group F are heavily dependent on them coming away with three points against Sweden, their last match in the group stage. It was continually one of the biggest weaknesses that El Tri had throughout qualifying and the Confederations Cup. Through solving the calamities that come from long balls and knockdowns, Mexico’s chances will improve to go into the later rounds.

Transitions

Akin to Pep Guardiola’s teams throughout his career, a pivotal moment of focus for Osorio’s strategy of ball retention and dominance is centered around the moments after possession is lost. Oddly enough however, it has also been a weak point under Osorio, and an area he has moved to fix over the past twelve months.

Positional Elements and Consequences in Transition

- Counterpressure

The numbers that Mexico gather around the ball in attack aids their counterpressure, provided that they lose the ball higher up the pitch rather than closer to goal. By having many players available for short passes in a tight space, distances to close down the ball after ceding possession are reduced. This results in players having to run less to get to the ball and more players able to help pressure or cover solutions out. Over the course of a game, players will end up running less and are able to preserve their energy for attacking actions.

This is only if the counterpress is performed ideally. While it has improved lately, this was an inconsistent area in Mexico’s 2017 matches. For example, Marco Fabian is quite good with his counterpressure and having quick reactions to pressure the opponent. On the other hand, Carlos Vela and Giovanni are a toss up. Counterpressing is never the responsibility of a single player, as even one player not participating around the ball can lead to the efforts of those attempting it to fail. Osorio has done better with his selection to choose players that are responsiveness to changes in phase and react quickly to losing the ball.

The counterpressure itself is particularly ball-oriented, with supporting pressure contributing to efforts to tackle rather than cut off passing lanes or surround the player. In fact, each Mexican player essentially picks up a man to prevent passes out of solutions, and once the pass heads towards their guy, they then approach at a high intensity. From the resulting closing down of space, Mexico hopes to win by either forcing an error or on the tackle if they attempt to dribble past.

- Rest Defense

As mentioned earlier, Mexico had some distance issues in possession with the 8’s, with the corresponding corrections and modifications discussed at length. From a transitional sense, it leaves Herrera with less space and players to cover in the centre once the ball is given away. These changes to the positional side of things in the 4-3-3 provide additional central stability, adding insurance on giveaways during early stages of build up. The narrow positioning of Salcedo during Mexico’s possession in many matches was also a mechanism designed to add stability for defending counter attacks.

When he features there, Alvarez will not stray too far from that role and Osorio will leave three defenders in the back commonly. With a holding player in front, they will have the centre secured. This will be the same case if they play with three central defenders, so their approach to defensive transitions and prepping for them during attack is relatively constant. If they can delay opponents and force them into wide spots, their transition woes of this time last year will vanish.

One possible weakness of Mexico’s defensive transition that is a recent development can be focused to Jesus Gallardo. The winger-cum-fullback has had some growing pains as he adjusts to the demands of a new position and role in Osorio’s line up. He has yet to be seriously tested defensively from an individual perspective, but there are some glaring trends about his transition behavior. His role by design is to get him into attack, so his high starting position isn’t the criticism. Rather, when the ball is lost, particularly on the far side, the speed of his recovery to get back into position is less than ideal.

It’s not only his rate of recovery, but the positional habit of it as well. The space between him and Moreno is what opponents will target on transition, and if Gallardo remains wide when he tracks back, he will afford more space for forwards to run in behind Moreno untracked. Gallardo’s first priority should be to recover diagonally, to combine closing both the space behind him and between him and Moreno.

Attacking Transition

Some sides in this tournament will be heavily dependent on attacking transition as a means of capitalizing on errors from the opponent or using the players abilities to their maximum potential. Mexico will not be heavily dependent on it, but for all the emphasis on the positional components of their attack, the transition side of things is not neglected by this coaching staff. There are two moments of a match where counter attacks are integral to the Mexican strategy: opposition set pieces and when opponents are chasing a result.

During opponent set pieces, Mexico will leave up two players with an additional one just outside the penalty area or ten meters beyond the taker. If the goalkeeper manages to catch the ball, he will immediately throw the ball into the path of one of the higher players to commence a counter attack. Guillermo Ochoa is especially strong in this area, one of the main reasons he has established himself as Mexico’s #1.

After the opponent commits their defenders forward for the set-piece, Ochoa quickly throws it to Hernandez once he gets hold of the ball, starting a sequence which leads to a goal.

Juan Carlos Osorio’s approach to attacking transitions when his team is leading is quite interesting. Most managers would use their lead as a security blanket, having more defensive possession, taking less attacking risks, and being savvy in their game management. Mexico of course uses this when applicable, but Osorio actually increases the amount of transitional risk he subjects his teams to when the opponents are in need of a goal. Sensing desperation kicking in, Mexico will look to counter the counter attacks when stopped, and Osorio has even made some substitutions that show Osorio looking for goal difference rather than just three points.

Take for instance the World Cup Qualifier at Costa Rica. Sometime around minute 60, Tecatito enters the match for Guardado in a like for like subsitution, sensing the new dynamics of the match and wanting the Porto attacker to push the tempo in search of a second goal. An unexpected move considering many managers make defensive substitutions when ahead. Yet Osorio eight minutes later makes another attacking minded change, this time Carlos Vela for Giovanni Dos Santos, having Vela function as a second striker-midfield hybrid to have four players contribute to counter attacks when possible. This sort of risk taking did not pay off in the end, as Mexico conceded one late to draw. But it shows the mindset and value system of Osorio, always looking to attack and exploit faulty areas of the opponent’s strategy and tactics. Who knows what wild changes we may see in Russia, but they likely will not be overwhelmingly defensive.

Set Pieces

Mexico’s set piece situations have been a key source of goals and high quality chances during Osorio’s time as manager. Their main strategies are not overwhelmingly complex for free kicks and corner kicks, but nonetheless have some interesting components.

On corner kicks, Mexico oftentimes place two players over the ball. One will be a right footed player, the other left footed, thus making the opponent unsure of whether to delivery will swing towards the goal or away from the goal. With the service, the gap between the penalty spot and the top of the six metre box is the most frequent target. When he’s playing, Raul Jimenez is the primary target of the deliveries, as his aerial ability is among the best in the tournament. From there, the surrounding players open spaces for Jimenez to move into to attack the ball, while players in front of him situate themselves just in front of the goalkeeper to get any rebounds or knockdowns.

Similarly with free kicks within scoring range, Mexico place multiple players over the ball to add variation. Equipped with many long distance shooting threats, direct set pieces within thirty yards will be considered a goal scoring opportunity for El Tri. Hector Herrera, Fabian, Guardado, Vela, Giovanni Dos Santos, and more are players dangerous from free kicks, with variations that are bound to catch teams by surprise. Not only are Mexico challenging to prepare for in the run of play, but additionally during set piece situations where they have a litany of options to use.

Conclusion: On Osorio’s “Tinkering”

Sometimes winning isn’t enough. Juan Carlos Osorio in particular likely understands this better than many managers, as he is polarizing and unpopular in Mexico despite his winning percentage being the highest among managers in charge for at least 20 matches. Why exactly does this manager in particular elicit such a strong reaction from Mexican fans?

There are several reasons which happen to irritate at least some fans. Being a foreigner doesn’t help his cause for getting the nation behind his team, and even if most Mexican fans would never admit to this sort of xenophobia, there is enough of a force in the nation that demands that the national team manager be from Mexico. Additionally, there is the common criticism of playing players out of position, subsequently ignoring other suitable talents in the player pool that mainly feature in these positions.

Leading up into the tournament, the main targets of these critiques will end up being Jesus Gallardo, Miguel Layun, and potentially Carlos Salcedo. Gallardo, a winger converted to left back for this team, is reminiscent of Michel Bastos’ metamorphosis when playing for Brazil in 2010. Both have similar playing styles and defensive issues, but were seemingly integral in the overall cohesiveness of the team when they play. Salcedo and Layun’s importance strategically were already discussed.

Osorio is far from the first manager to play a player “out of position”, but the main clash he faces is with fans who think about football in a rigid manner. No longer are the days where a player spends his career playing one role in a similar style throughout it. High level modern football requires the players to be universal and malleable, able to adapt to the changing dynamics of the opponent in the flow of a match. Most of the players called up to the 23 have featured in multiple positions for him, hence exposing his players to situations that Osorio can call upon in case a certain solution is required.

This is not the case where the whole squad are jacks of all trades and masters of none. Rather, they are comprised with specialists who can also dabble into other trades when called upon. With only three substitutions in the sport, having rigid players leads to rigid teams that are inflexible when their way of playing isn’t working. The fluidity among the roster to slot into places that are “not their normal position” makes Mexico more proliferous with the options they have on the pitch, not the other way around. Recent times have shown Germany and Spain being the beneficiaries of a polyvalent roster in international play, so what Osorio is doing here is not uncharted territory.

In line with the elastic profile of the team brings the biggest point of contention among fans: the lack of consistency in selections. 48 matches, 48 different starting lineups. Such a feat is likely unprecedented in international football, but it is not as catastrophic as some make it out to be. The development of meaningful team chemistry in international football is constantly being interrupted, with the only prolonged periods of team activity being the tournaments themselves.

Tournaments see the selection changing due to form, injuries, suspensions, and more, suggesting that on field team chemistry itself is a marginal concept in international football. In fact, the best teams in the history of international football had a bulk of their players come from 2-3 clubs, suggesting that team dynamics and chemistry from club football translates to international success when integrated properly. No matter how much chemistry a national team can develop, it cannot compare with daily club interactions.

From Osorio’s vantage point, his perpetual changing can be explained for multiple reasons. If you didn’t catch the tactical reasons, do yourself a favor and re-read the entire piece again. The other reason behind it that is overlooked is the fitness component. His initial background in football was as a fitness coach, and perhaps during his years of experience, he began to subscribe to the belief that teams with fresher players have a better chance of winning. This is because the fresher team will be able to perform their football actions at a higher intensity than a team with more fatigue. The supposed valuing of freshness by Osorio isn’t speculative, being supported by the hiring of sleep coaches for this summer’s tournament alongside giving his players workout regimens to perform at their clubs for preparation. Fitness wise, no stone can be left unturned to have players perform to their maximum potential.

This would adequately explain why Osorio would change five or six players from one match to the other during international breaks and tournaments. It also explains why key players would not start important matches during the first match of an international weekend, or resting most of the starting XI against New Zealand in the second group stage game of the Confederations Cup. Even if the first game was important, Osorio viewed the next fixture as more important, thus wanting his best players to be as fresh as possible for that game.

This way of thinking is unorthodox among coaches, but Osorio himself is unorthodox. There is so much that cannot be predicted with this Mexico team, whether it be their starting selections, how they will move forwards, the volatility of their transition game, or their halftime adjustments and substitutions. However they turn out in Russia, it will in the quest of controlling the opposition, using every resource and bit of information possible, with Osorio under the microscope with every choice. In the midst of all the uncertainty with this Mexico team, there is one thing which can be predicted, and that is they will be one of the most fascinating tactical watches for the World Cup.

Special Thanks to Erick Villicaña Gomez and Eddie Schmidt for providing help and support to the writing of this piece!

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

smoc June 18, 2018 um 3:25 pm

wow.. impressive! thnx