Atlético Madrid cede possession in order to win another Europa League trophy

Atletico Madrid triumphed in a European final for the first time since 2012 by beating Marseille 3-0 in Lyon. The match was characterised by Atleti excelling in all defensive phases and turning regains into swift counter attacks.

High-Pressing and Mid-Pressing

High-Pressing and Mid-Pressing

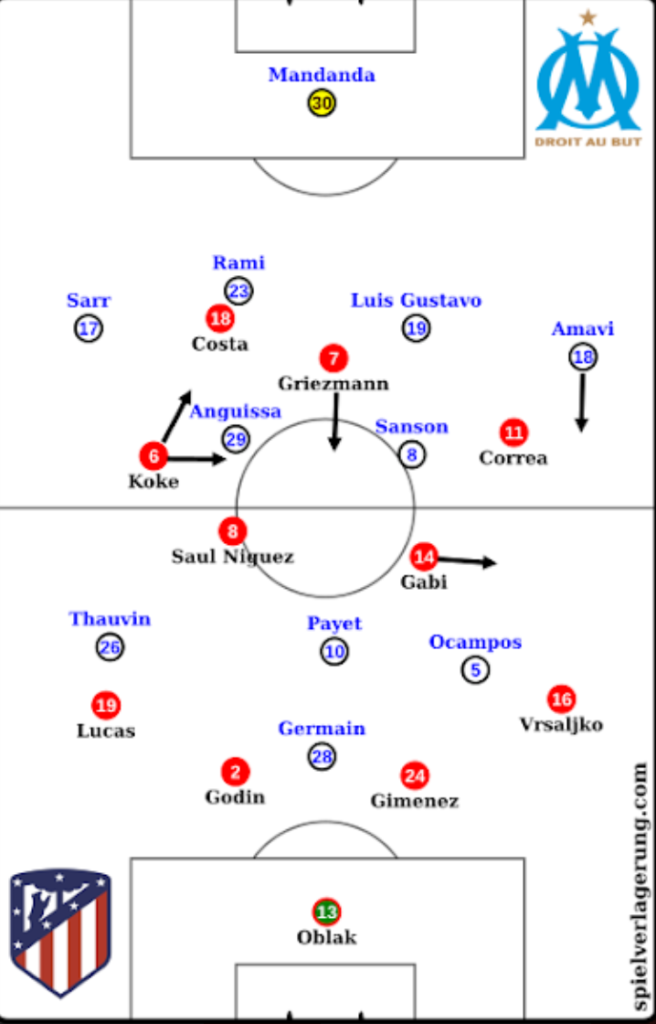

Diego Simeone has created a side that, for a number of years, have shown to be one of the best teams in the world at defending in a mid-block. That said, he structures his sides to be so adept at setting pressing traps that, even with bigger spaces such as during high-pressing and certain moments of middle-pressing, they are able to push for regains. The profiles of the side’s front six allow the team to aim for turnovers at the same time as being able to cover long passes over the first two lines of pressure. The speed of Correa and Griezmann, as well as well-honed spatial understanding, allowed Atleti to often press with 5vs6 or even 5vs7. Koke, too, positioned himself often in between at least two Marseille players to set pressing traps or dissuade Marseille from short build-up. Gabi was often used as a balance player to block clipped passes, whilst Saul has excellent power in duels as well as superb acceleration so was able to cover huge potential spaces in pressing. Costa, though more passive, was often used to man-mark a centre-back in build-up phase one, and a number six in phase two. He also was ready to charge down the goal-keeper with an arched run to rush Mandanda into kicks.

From goal-kicks, Marseille did not build-up, and so high-pressing was only really triggered when play was forced back to the goalkeeper. Structurally, the role of Koke and Correa was to defend zonally inside the halfspaces when Mandanda had possession. Gabi and Saul would move up or down according to what side the ball had come from. When the ball moved back to Mandanda from the left centre back, Gabi would move up onto the left number 6 to invite a pass to the right number 6 and Saul would do the same on the other side. The other, in turn, would drop to block clipped passes into Payet in the centre circle and create a 4vs3 overload in the defensive line. Griezmann or Costa would follow the ball if it had travelled back from their side, blocking the pass back with their cover shadow, whilst the other would stand just inside the centre-back ready to trap the invited pass into the number 6 close to them, who had otherwise been left open to invite the pass from Mandanda. When the pass back came from the right centre back, Correa was able to cover the left number 6 as well as the left back, due to his speed and acceleration. When the ball came from the right side, this was left for Gabi to cover both players as Koke was not able to sprint across as quickly.

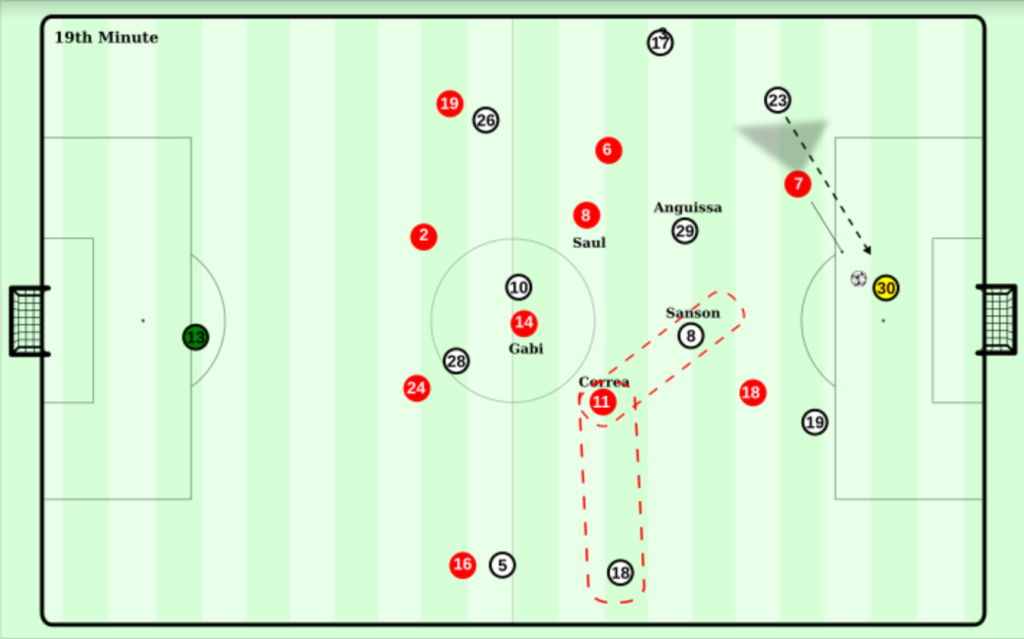

In the 19th minute, with the ball coming to Mandanda from Rami at RCB, he was dissuaded from passing to Sanson, despite a punched pass into the player’s left-foot realistically giving him enough time to turn, shield and carry the ball or pass. Griezmann followed the ball to press Mandanda, who decided to clip over to Amavi, who was immediately hunted down by Correa to force a throw-in. The distance between Correa and both Sanson and Amavi was 15-20 metres, and so his extreme speed is clearly a major asset here in order to set such big, and convincing, pressing traps. Under a minute later, with the ball coming from Luis Gustavo at LCB, Mandanda opted for the other option, which was to pass to the seemingly free number 6. This time Gabi left Sanson on the ball-side to sprint towards Anguissa, whilst Griezmann moved inwards to backwards press. The job of both was made easier, however, by Anguissa’s miscontrol, which fell straight to Gabi allowing him to assist an easy goal for Griezmann. (See High-Pressing Diagram)

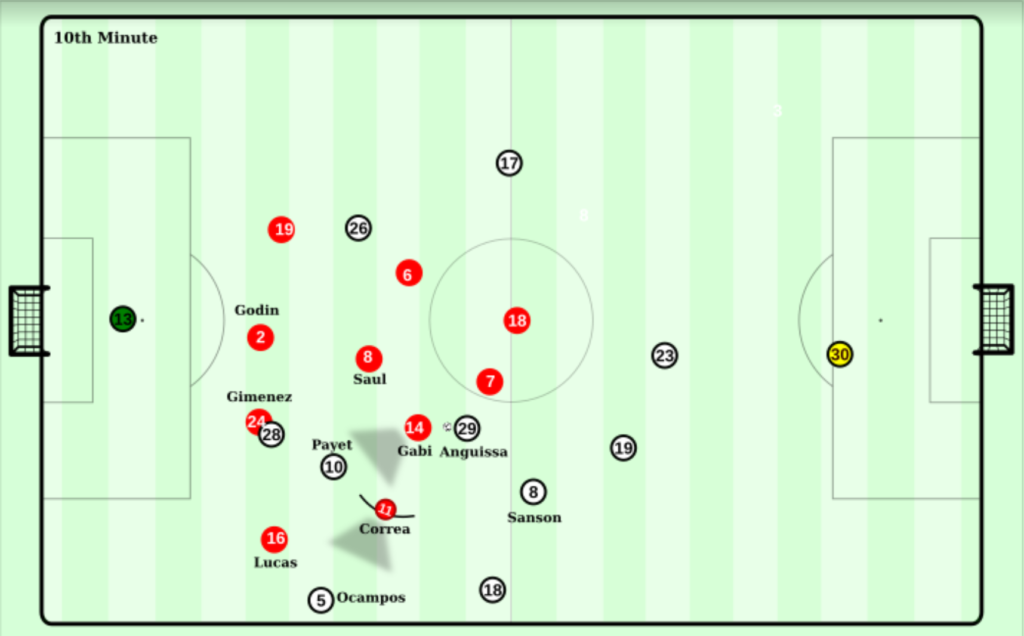

Atletico Madrid are a fascinating team because they have the players to circulate the ball and build attacks through positional possession, however they often spend games forcing duels through long balls, quick clearances and direct passes. These, of course, often fall straight to the opposition, yet they are so comfortable defending in every phase that, in this final, they happily offered Marseille the ball in order to force regains and transitions. Marseille did not spend much of the game in build-up phase two, however, as they responded to Atleti’s directness with a similar style. When they did occasionally enter this phase, Atleti used a 4-4-1-1 zonal shape, with quick man-orientated movements once Marseille played into the intended trap. Costa would largely occupy Rami, thus forcing Gustavo to take the ball. Griezmann would begin in between the two number 6s and slowly close down Gustavo who would now be edging wider. In doing so, Griezmann would move infront of the ball-near 6 and often block both Sanson and Anguissa with this cover shadow as the pair rarely moved off the same horizontal line, whilst also allowing Costa to move onto the ball-far 6. Correa and Gabi would now stand in between Amavi and the 6 that Griezmann had now left, Sanson, setting two traps, with any pass being immediately pressed from both players. If Payet dropped infront of the midfield line, Saul or Gabi now were able to aggressively press from behind, with no worry for Germain on the last line who was occupied by both centre-backs. This pressing movement was often continued down the line of any set-pass from Payet to create even more pressure and force clearances.

Even when Marseille moved into a situational back three with right back Sarr coming down into the defensive line, Marseille were not able to access this switch pass as Gustavo was pressurised from the inside, whilst Rami was always occupied either through Costa, or one of the striker’s cover shadow, whilst Koke could now move inside due to Sarr doing the same, making a 3vs3 in the middle. Equally, when Marseille played with a 4-3-3 shape after Payet’s injury, Costa and Griezmann were so adept at forcing the centre-backs to pass wide, that Gabi or Saul could move to the nearest centre-midfielder and block at least one of the other two with a cover shadow. This was not helped by the Marseille midfield’s lack of staggering in possession, and even when both Atleti centre-midfielders came over to the side to outnumber and force throw-ins, Marseille could not find access back into the centre due to the the striker’s and highest centre-midfielder’s body shape to force the ball to the sides. When pressing and counter-pressing on the sides, especially in Marseille’s half, Atleti would use a three-pronged pressing trap. The first player would rush towards the ball and usually show outside, the second would block the open passing line infield and guide towards a teammate down the line, and the third would be ready to press this pass aggressively. (see 3 pronged pressing diagram)

The Atleti players’ positioning and timing would not be anywhere near as effective as it was if not for their individual prowess in duels. Every player shows incredible tackling technique, body positioning, aggression and intensity to make 50/50s in actual fact 70/30s. This aspect of their game cannot be understated, and each player is also extremely adept at winning free-kicks and forcing set-pieces when they need to. Seeing as they each attack duels with such intense aggression, they trigger the same level from the opposite player. Instead of absorbing this impact, Atleti players cleverly invite a foul, allowing them to turn long balls into free-kicks in high areas, and relieve pressure in their own defensive third on countless occasions.

The Atleti players’ positioning and timing would not be anywhere near as effective as it was if not for their individual prowess in duels. Every player shows incredible tackling technique, body positioning, aggression and intensity to make 50/50s in actual fact 70/30s. This aspect of their game cannot be understated, and each player is also extremely adept at winning free-kicks and forcing set-pieces when they need to. Seeing as they each attack duels with such intense aggression, they trigger the same level from the opposite player. Instead of absorbing this impact, Atleti players cleverly invite a foul, allowing them to turn long balls into free-kicks in high areas, and relieve pressure in their own defensive third on countless occasions.

Staggered Mid-Block

When Marseille were able to avoid the aforementioned pressing traps, they came up against a mid-block that has been a large part of the reason Atleti have conceded just 18 goals in La Liga this season and only 7 in 12 European games. Atleti stagger their midfield four chain, with controlled pressure on the ball carrier and passes into depth covered through the second centre midfielder. As an example, when Anguissa was able to be accessed by Gustavo, or picked up a loose ball and drove past Aleti’s first line, the nearest CM would press down the line of the ball with a neutral body shape, whilst the adjacent one would drop. If the pass was to be played square, the pair would pendulate accordingly, with one moving up to the ball and the second dropping. Usually Griezmann would block any square pass by positioning himself in between the two 6s, meaning the play would gradually move to the wings where it would be trapped by wide player and full-back. The Atletico wide players would, like in the other two pressing phases, position themselves in the halfspace, fully aware of where the Marseille winger was. If he was in the inside pocket (the space in between full-back, centre-back, wide player and centre midfielder), they would show in to invite this pass to be trapped by the full-back. If the winger had moved wide instead, they would then invite this pass into that area so the fullback could trap the play wide.

It is interesting that they invited passes to rather than away from opposition players, yet this again is down to Atleti’s superiority in duels, and they would even defend wide, with an inwards body shape when the winger was behind them and Payet was inside. As the diagram shows, Gabi’s forward facing pressure next to Correa’s inward body shape was enough to threaten to trap this potentially dangerous pass, while the former blocked the pass to the winger with his cover shadow.

Sometimes, however, this created a potential problem for Atleti as, for example, a pass into Ocampos was not met with perfectly timed pressure from Vrsaljko, who could therefore flick the ball outside to Amavi. Even in the diagram, a laser pass into Payet’s left foot would have posed a potentially dangerous situation for Gimenez and Vrsaljko, yet presumably Marseille were dissuaded from risky passes due to Atleti’s continued success in pressing traps. In the first case, Amavi’s only option was to cross, seeing as Ocampos did not make a diagonal run towards the corner flag in between the Vrsaljko and Gimenez. Atleti were then very happy to defend the box with the aerial abilities of their four defenders, and with Gabi dropping down into the defensive line to always have an overload of at least 1.

Switches were also dealt with well by Atleti, as Correa and Koke reacted to an indication of a switched pass such as a touch out of feet, by sprinting out to the opposite full-back as the ball landed. They did not need to be concerned with a disguised pass inside them, as Griezmann, Saul and Gabi expertly used their cover shadows to block spaces they knew their teammates were moving away from. This, again, allowed Atleti to cover multiple passes from one position. With Marseille’s inside forwards being positioned very centrally, Atleti’s full-back on the far-side was able to match any movement across to support the pass. Griezmann, the far centre-midfielder and Costa then sprinted over to block passes into the supporting Marseille 6, while the other centre-midfielder came across too, to block passes in between the lines. Again, these actions are all within a framework of intense speed and agility and extreme concentration so that in transitional moments when Atletico are moving across the pitch and open to more overloads or 1v1s, they can block spaces and delay. The rare times in which Marseille broke through Atleti’s mid-block, such as when they managed to pin back a full-back with a midfield runner and find a pass to the winger, Atleti moved into incredibly compact, and aggressive, low-defending, with 2 extremely narrow lines of four condensed within 20 metres horizontally and 3-4 metres vertically, inevitably forcing turnovers.

Forcing duels with good positions for second balls allowing effective transitions

When Guardiola says that he had to get accustomed to focusing on positions for second balls as this is uncommon in Spain, he is definitely not referring to Atletico Madrid. Simeone’s side are incredible at positioning themselves effectively to counter-press and turn duels into effective transitions. One moment in which they try to force potential transitions are from throw-ins. Often aiming kicks towards Costa on the touchline to force throw-ins (for or against), they then get ready to win an aerial duel, the second ball and attack the open spaces created by the opposition condensing the touchline. Throw-ins are, generally speaking, still one of the least structured moments of the game, and we will presumably see a lot more tactical analysis around them in the coming years due to their incredible strategic potential. That is not to say some teams do not structure throw-ins, but that there is also little exterior focus on this. Watch this space….

For offensive throw ins, Costa would be the highest player and would occupy two Marseille players, with Anguissa front screening him. In front of Costa, the near side wide player would be ready to spin and pick up the second ball, whilst Gabi, Saul and the ball-far wide player would be ready behind Marseille’s centre-midfielders to aggressively press their backs when the ball landed with them. All the while Griezmann positioned himself in between the ball-far centre-back and full-back so they could not step into the middle to collect second balls, and for deeper throws he would stand around the deepest Marseille 6 to help collect second balls in front of Costa. Atletico capitalised hugely on Marseille’s tendency to bunch around the ball to support duels and to face the ball and their own goal. Both of these relatively natural reactions to defending long balls allowed Atletico to aggressively press from behind and, with their superior pressing traits, they were able to win possession.

Marseille throws also allowed Atleti to launch counter-attacks and, with Griezmann positioned deeper to occupy Anguissa, he was used in his typical “launchpad” role for counters. Atleti aggressively attacked loose balls in the direction of Griezmann, whose set was joined by bursting runs past the Marseille midfield line from his midfield. Koke, especially, was used in this way and his position is anything but a wide-left player on transition. He instead capitalises on immense ball-orientated pressing around his quick and nimble teammates, Correa and Griezmann, to move behind the midfield pressure and into open pockets in front of the defensive line. He did this on multiple occasions, and cleverly stepped behind the Marseille line as they burst forwards to challenge the ball. The contrasting momentum here, with Koke predicting his teammates were going to win loose balls, gave him a big advantage to attack the now open central spaces for counters. With Koke, Correa and one midfielder running centrally on counters, any lost balls were quickly counter-pressed in the centre and around the edge of the box. Both Atleti’s second and third goals came from a Marseille throw on the left-side, with a quick regain into Griezmann starting the attack and ending with an assist from Koke. A hugely devastating and effective use of opposition throw-ins to start counter-attacks.

Right side breakthrough and set-pieces

The rare times in which Atletico utilised their excellent capacity for ball circulation and retention were during the second half. Marseille were largely in a 4-3-3 formation after Lopez had come on in place of the injured Payet. To counter the overload in central areas, Atletico brought on Juanfran for Vrsaljko and dragged play over to the right side, bringing Koke into the centre and even the right halfspace. At the same time, Atleti would put two to three players on right touchline, with Griezmann and/or Gabi joining Juanfran. With Correa and Koke moving infront of the defensive line, they were now able to outnumber Marseille on this side with late movements forward from Juanfran, escaping N’Jie, or with Saul becoming spare. This allowed a switch to Lucas, seen on one occasion, but more common were quick forward movements and rotations from Griezmann or Costa on the last line to drag Amavi or Gustavo out of position. With Atletico’s ability to retain the ball in extremely tight areas, they were able to even play heavily outnumbered and find openings, with Juanfran breaking in-behind having opened a passing line outside Amavi after successfully playing 5vs7.

In a similar fashion, Simeone used corners to pull Marseille players towards the ball before probing the penalty box. Atletico usually brought two or three players out of the box, including the corner taker. This forced Marseille to bring two players out and often keep a third back defending an Atletico player on the near touchline, with another on the edge of the box for second balls. When Atletico finally left Marseille with only 6 players in the box, they then crossed the ball for one of their four players to attack. Again, the ability of Griezmann and Koke to keep the ball against intense pressure, whilst waiting for the right opportunity to cross, gave the side great potential in finding overloads in the penalty box. Juanfran almost scored at the near post after a situation just like this.

Conclusion

Atletico Madrid continue to be one of the most fascinating teams in world football, as well as one of the game’s greatest paradoxes. By both sharing Guardiola’s love of the ball, and Mourinho’s indifference to it (if not in exactly equal measure), Atleti continue to be one of the most efficient teams in the world and triumphed over a Marseille team that had knocked out some excellent sides on its way to the final. It is yet to be seen whether they can keep hold of Griezmann to launch a “third time lucky” assault on the Champions League in 2018/2019.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Jiddu May 22, 2018 um 10:13 am

Can Spielverlagerung do an article on how a novice can start analysing matches? Like what are the basics, the important things to look at. Maybe it will help us more in understanding the analyses here . Thank You.