How Pep’s Citizens have taken over England

Under the guidance of Pep Guardiola, Manchester City have become a dominant force domestically and a serious contender for the Champions League title. We break down what has led to their current success, what makes them special, and why they seem almost unbeatable.

This article was co-authored by Constantin Eckner (CE) and Austin Reynolds (AR).

As of publishing time, the Citizens have won 28 of their 31 competitive matches this season. The only defeat came against Shakhtar Donezk in the last game of the Champions League group stage when City had already secured a spot in the round of the last 16. After an expected rough first season under Guardiola, City are now undeniably among the best sides in European football, which is reason enough to take a closer a look and examine specific (tactical) reasons for their current success.

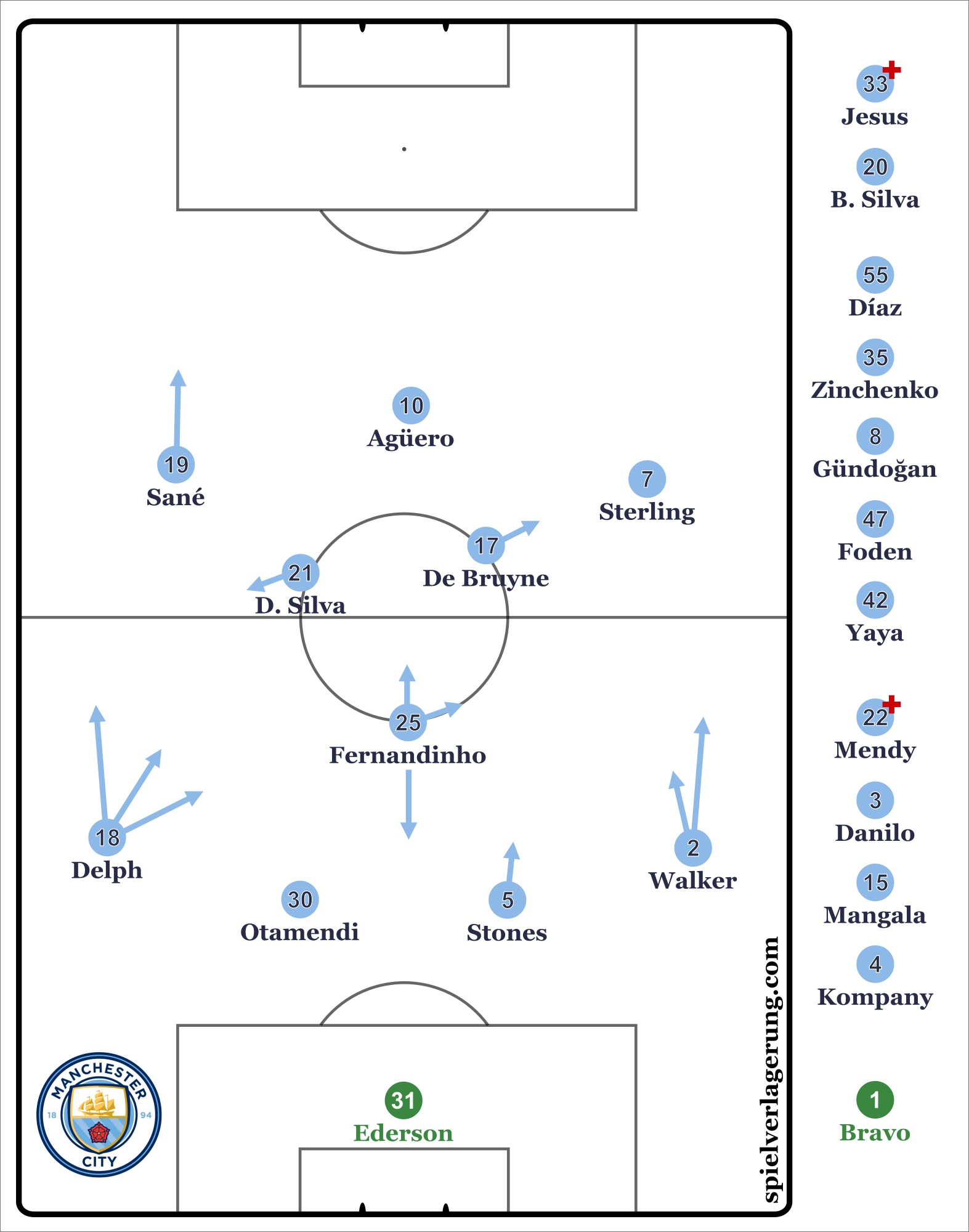

Squad and line-ups

The marriage between Guardiola and Manchester City seemed perfect from the start. On the on hand, there is a world-class coach famous for his methodical work and the aptitude to build up dominant teams with a possession-heavy style. On the other hand, there is Manchester City, a club ready to give the wheel to a coach who could lead them to new heights. City have been a member of the nouveau riche club for quite some time but are still waiting for the breakthrough internationally. Considering the hundreds of millions that have been invested in the team since the Abu Dhabi United Group took over in 2008, the output in terms of titles and reputation beyond the borders of the United Kingdom has been quite underwhelming.

Guardiola likely took into consideration that City would likely hand him over the credit card to go shopping on the transfer market. Only romanticists would believe the goals City and Guardiola have are achievable without a quality squad, even when a top-three coach like Guardiola is in charge. The Catalan showed at Bayern Munich he can conceal the decline in individual quality for some time, but building up a new force in European football is a different task.

In the past 18 months, City have spent around 463 million Euros for new players while selling players worth a combined transfer fee of 130 million Euros. Instead of investing money for two or three signings like Paris Saint-Germain did last summer, City spread the money and bought five players for something over 50 million each in John Stones, Leroy Sané, Bernardo Silva, Benjamin Mendy, and Kyle Walker. The addition of Mendy and Walker prior to the ongoing season notably showed how Guardiola and the front office intend to fill every spot in the starting eleven with high quality. Bit by bit Guardiola is putting the team he needs together.

What City still lack at the moment is depth across the board. While they have two players for each position at the back, midfield and attack appear to be a bit thin. Until İlkay Gündoğan came back from injury and was in shape to play more than just a couple of minutes, City had to rely on the same midfield line-up over and over again. And even with the addition of Gündoğan, there is no considerable replacement for Fernandinho, the holding midfielder in City’s customary 4-3-3 formation.

Phil Foden and Brahim Díaz, two of the few former academy players who are anywhere close to a regular spot in the matchday roster, and Ukrainian all-rounder Oleksandr Zinchenko may end up with more minutes than initially expected, which shows how City have quality but not necessarily en masse. The same is true for the front three where Guardiola can choose from five high-calibre players in Leroy Sané, Raheem Sterling, Bernardo Silva, Gabriel Jesus, and Sergio Agüero. Up until now, City have only suffered two major injuries—Mendy’s ACL tear in September and Jesus’s MCL damage just recently—but should injuries pile up at one point it may destroy their hopes of a picture-perfect season.

Formations

After the early phase of the season, when Guardiola tried out a 3-1-4-2 in three of the first four Premier League matches, he established the 4-3-3 as the go-to shape and only occasionally changes the structure significantly, as he did against Newcastle United just recently. The basic formation City employ does not provide anything spectacular. It is instead a rather customary shape which you can find across all professional leagues in Europe. The details, however, carry Guardiola’s thumbprint.

A key component of the current system regards the use of false full-backs. At first, it was mainly the right side that saw an unconventional use of the full-back, while, later on, Fabian Delph established himself as a special version of a left-back. Another key role is the holding midfielder. Normally played by Fernandinho, the no. 6 in the City system serves as what is sometimes called a “midfield libero”. The term means that instead of moving up and down field, the no. 6 is specifically responsible for covering the two or three players in front of him, while also providing additional protection at the back, especially when one of the centre-backs advances in build-up or is pulled away due to strict man-marking.

A key component of the current system regards the use of false full-backs. At first, it was mainly the right side that saw an unconventional use of the full-back, while, later on, Fabian Delph established himself as a special version of a left-back. Another key role is the holding midfielder. Normally played by Fernandinho, the no. 6 in the City system serves as what is sometimes called a “midfield libero”. The term means that instead of moving up and down field, the no. 6 is specifically responsible for covering the two or three players in front of him, while also providing additional protection at the back, especially when one of the centre-backs advances in build-up or is pulled away due to strict man-marking.

Other than that, there is not much to say about the system on a macro-tactical level. Guardiola only occasionally experiments with role changes. He, for instance, fielded Sterling as what you may call a false no. 9 against Manchester United while positioning Jesus on the left which was a bit unusual but had its purpose. He also switched to a two-striker formation against Newcastle which worked perfectly fine. In most cases, however, the 4-3-3 with all the possibility to transform it in particular defensive or attacking phases is Guardiola’s preferred formation.

Match-planning

While it is almost impossible to make a general statement about Guardiola’s match plan as he usually adjusts how he and his team approach particular opponents, there have been tendencies which make sense in the context of City’s style of football. The Citizens appear to be slow starters. There may be some truth to that, but the main reason City have often scored their first goal in the second half has to do with how they methodically take over a match. Before committing to vertical passing and increasing the intensity, they intend to establish their dominance by long spells of possession.

Euan Dewar and Mark Thompson of Statsbomb pointed out in a November piece that, at the time of publishing, City averaged “over five sequences of 20 or more consecutive passes per game,” which is far more than any other team had ever done since Opta has been recording data. That City find their way into the final third in 55 per cent of their possession sequences emphasises how Guardiola’s idea of football is not only about establishing possession just in order to secure the ball and avoid any threat to their defence. City are determined to break down an opponent tactically and mentally, meaning they want to take away any hope that the opponents are able to create promising goal-scoring opportunities while also figuring out the weak spots.

That being said, Guardiola adjusts his match plan if he feels it is the appropriate decision to push the accelerator pedal right away. City did so in several high-profile matches against capable opponents such as Shakhtar coached by the very talented Paulo Fonseca, Tottenham Hotspur or Manchester United. They pressured their opponents from kick-off and kept the intensity high. Group-tactical dynamics and a high intensity-baseline have built the fundament on which Guardiola’s side can be successful. As mentioned before though, there is no general blueprint of how Guardiola plans out a game and how the City side change rhythms, intensity, and positioning. Maintaining a degree of unpredictability is crucial in today’s football, where even some web site may write a long form on your team’s tactics.

Build-up and transition into the second and third phase of attack

As with Guardiola teams of years past, Manchester City typically have a large majority in possession, fixated on how controlling the ball subsequently controls the game. Guardiola has instilled into his players a playing style that values “possession with a meaning”, or how each pass has an underlying intention of opening up spaces or moving around opponents. This is not Tiki-Taka, or possession for the sake of having the ball, but rather moving the ball to move the opponent. While the positional play footprints were there last season, this season has shown improvement in the principles and an evolution in Guardiola’s philosophy.

Issues of the 3-1-4-2

In the opening fixtures of the season, Guardiola tried out using three at the back to get the best out of his squad. During possession, City would be shaped in a 3-1-4-2 formation. Fernandinho would move in front of the defence, while the wing-backs would move high up the pitch, occupying their respective touchline and flanking David Silva and Kevin De Bruyne. Guardiola would field both Jesus and Agüero together up front as well. When using this system in domestic competition, the Citizens were unbeaten, but their play in possession was not always superb due to a series of issues with their organisation.

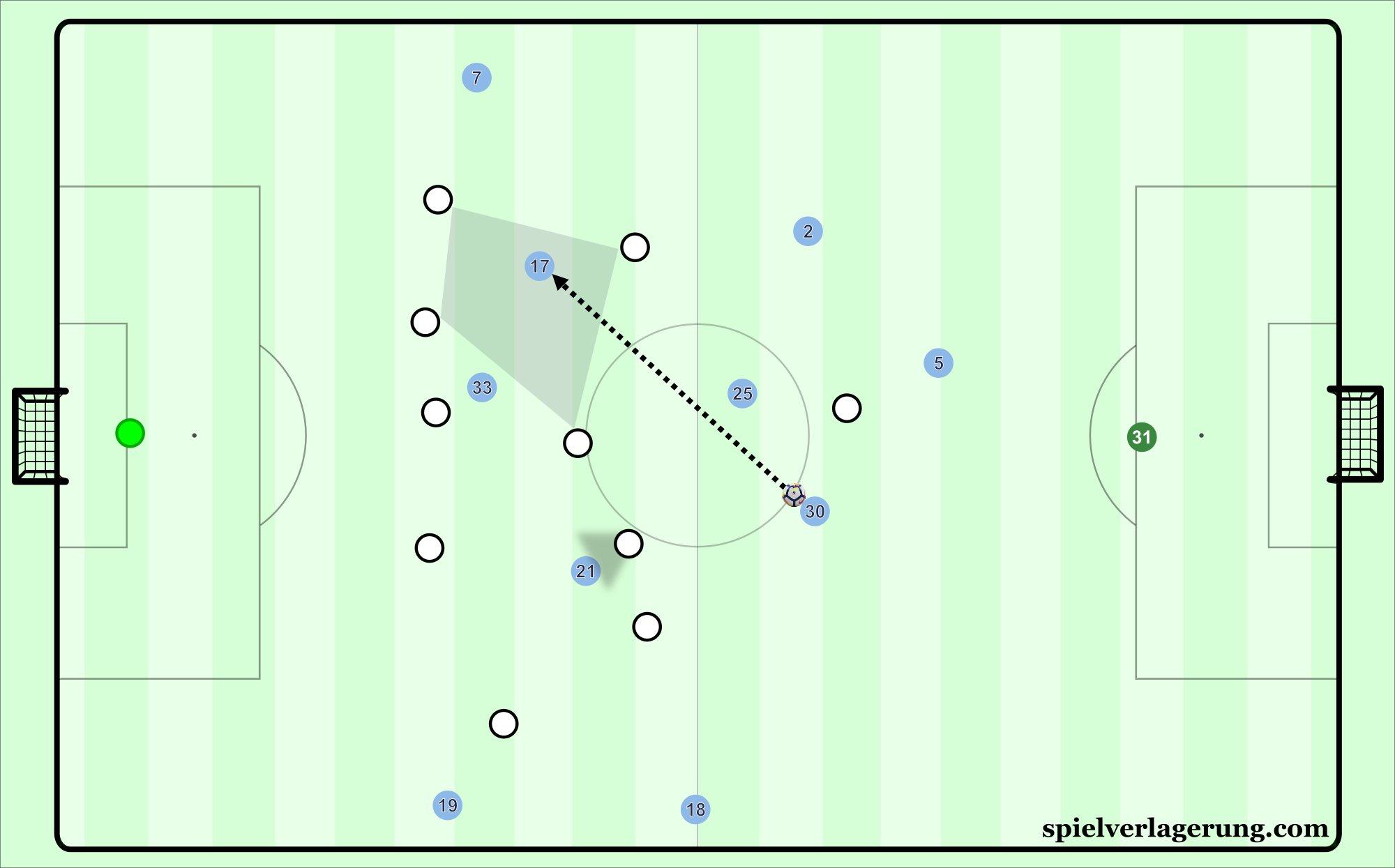

With City’s 3-1-4-2 formation, Fernandinho’s positioning is crucial for being able to connect the defensive and more advanced players of the team in possession. With many players ahead of the ball, he needed to be in positions where he could both receive the ball in valuable areas and pass to his team-mates ahead of him. However, the Brazilian frequently was not in good spots, as he would often be too close to the defenders, adding a higher degree of difficulty and precision to any passes played forward. Conversely, Fernandinho would on occasion position himself in close proximity to the attacking midfielders. The lines of four and two were also easily covered by opponents that demonstrated decent compactness. This was because in order to find any sort of space, there would be a high amount of interchanging and alternating positions between the no. 8s and the centre-forwards.

Situationally, this led to the lines of two and four becoming one horizontal line of six. This makes finding forward passes difficult for the centre-backs, as they are positioned so far from where the forward options are. Even if one of the forward options receives the ball, gaining anything productive from the attack is difficult because they are all positioned on the same line. The only way to get forward after that is either by dribbling or combination play, actions which require great skill to complete at high speed and do not always succeed. Such organisation is not optimal for mixing stability and risk in the build-up of attack. Because of the congestion in the forward line, a high amount of accuracy is required with the passes to play forward, which led several issues during City’s build-up.

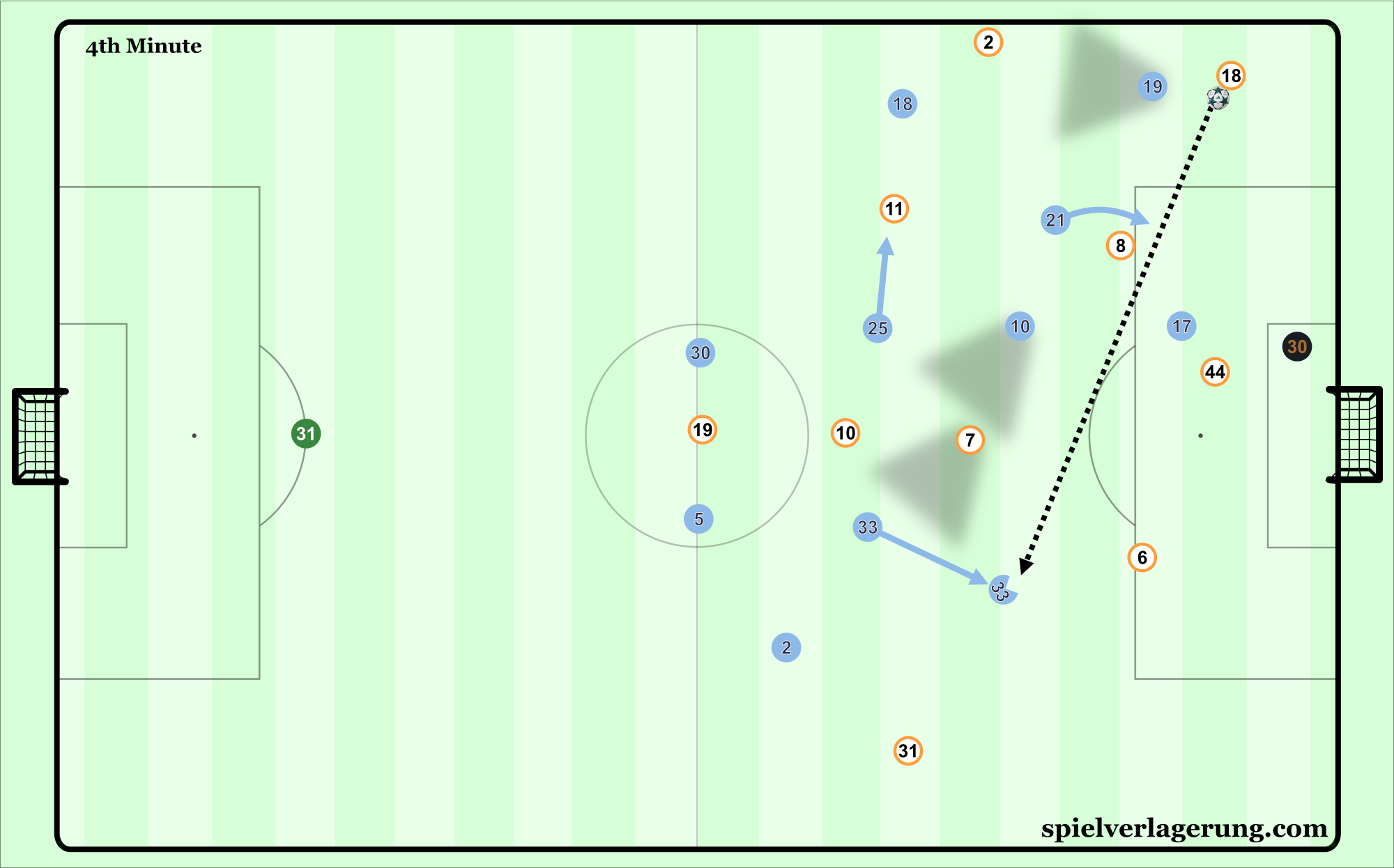

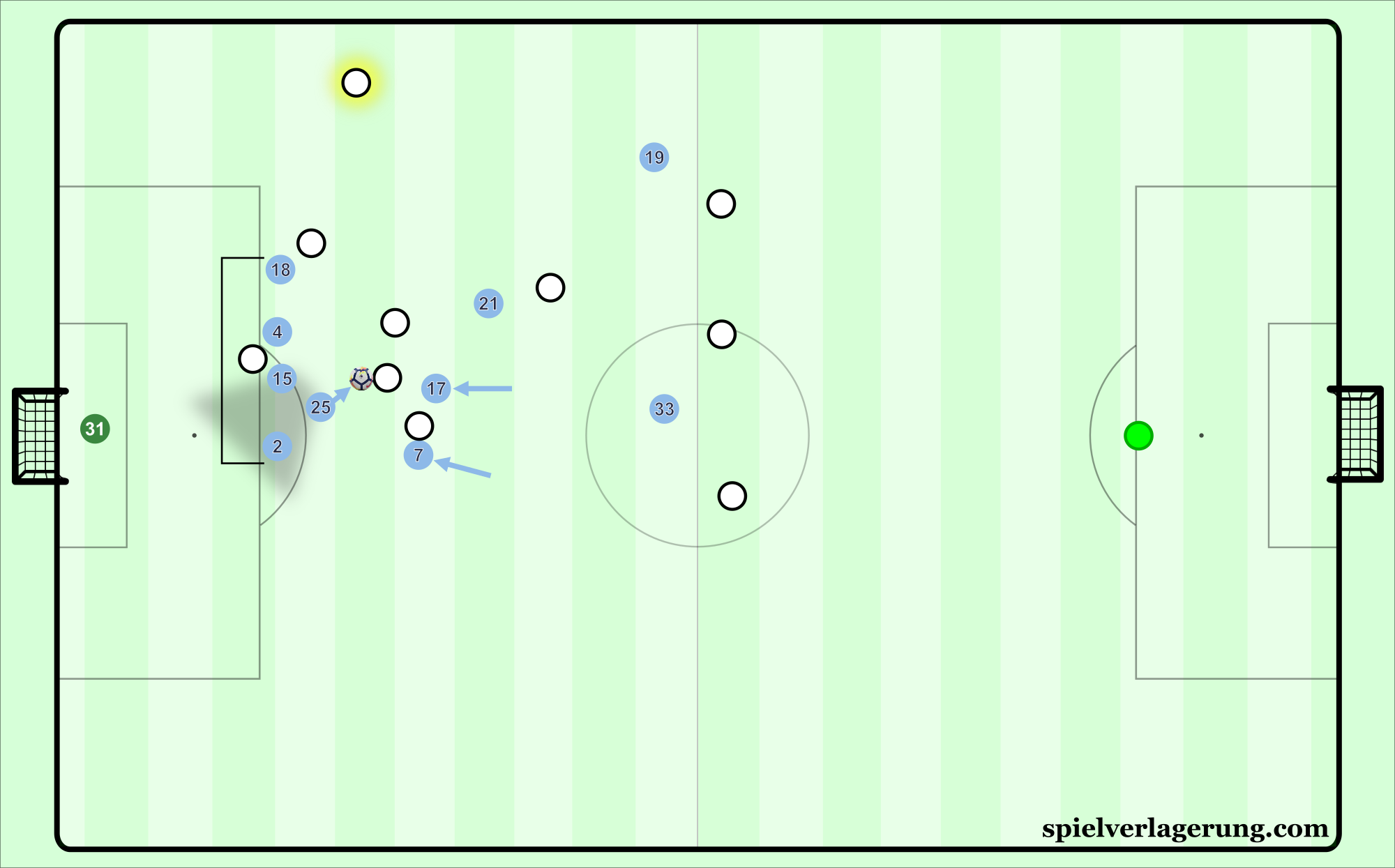

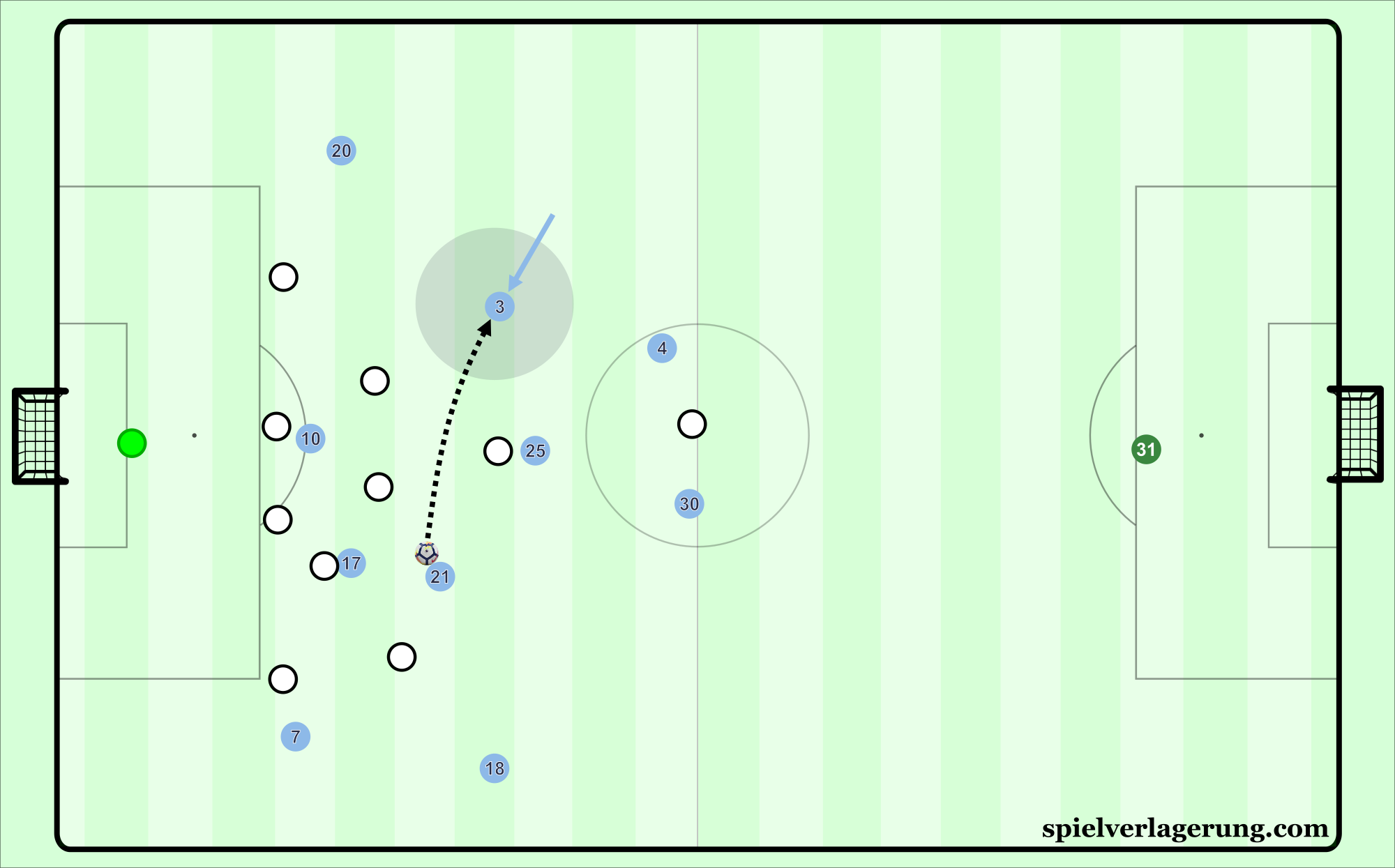

When Otamendi receives the ball here, every forward player is covered thanks to the compactness of the opponents. A horizontal line of six has formed in their quest to find the ball, which makes their attacking play in the final third more difficult because they are all on the same line.

These large distances often led to centre-backs dribbling forward to decrease the length of their passes. The speed of recognition is slower from the centre-backs than it is for a player like De Bruyne, so in the time frame they would dribble and wait for openings to appear, the defending team would cover any attractive decision. Following the dribbles, frequent examples of non-penetrative side-to-side circulation from the centre-backs occurred. In general, central defenders oftentimes possess less ability when it comes to playing passes with small error margins than the playmakers in the team. To avoid the risk of losing possession and getting countered, they would not play these passes and look to find openings on the opposite side. Repetition of this would occur as a result of these large distances from the back to the front of the team.

After a period of not receiving the ball, Silva and De Bruyne would naturally come deeper to get their share of touches, creating unnecessary superiorities in front of their opponent’s defence. Due to the proximity of the wing-backs and attacking players, it could easily be covered by a compact midfield and defence. This proximity is designed to facilitate high-speed combination play, but this particular shape pre-emptively helped the opponents, provided that they were willing to do the required shifting.

We covered some of these early season issues in our analysis of the opening match of the season against Brighton & Hove Albion. In the following matches, the distances improved, which led to better circulation of the ball and movement up the field, but there were still the same possession habits on display with the 3-1-4-2. Perhaps a no. 6 with better passing and positioning in possession would have allowed the system to work, but Guardiola instead opted to switch his primary formation to a 4-3-3, which has seen great success thus far.

City’s positional roles and behaviours

In City’s 4-3-3, the positioning and focus of the back four are dependent on the opponent. In some matches, both full-backs are utilised high and wide, with the wingers subsequently pinching into the creative zones of the pitch. On other occasions, false full-backs are used to establish more central control in deeper positions. More will be discussed about false full-backs later on.

Between the two centre-backs, Stones has been the more frequent passer and breaker of lines in the partnership with Nicolás Otamendi. With Stones more adventurous in possession, the Argentinian remains further back to cover and is the more conservative of the two central defenders. In the absence of Stones due to injury, Otamendi has taken up his responsibilities as the more frequent passer from the back. Captain Vincent Kompany has slotted into the more defensively-minded centre-back role recently.

The midfield generally comprises of Fernandinho operating as the no. 6, positioned ahead of the defensive line acting as the lone pivot. Silva and De Bruyne function as high no. 8s, typically found in the left and right half-spaces respectively. Both of them float into wide areas for combination play with wingers from time to time or swap with said players to create gaps in the opponent’s defence.

In terms of the normal responsibilities of the no. 8s in such a system, that position is usually required to stay in the half-spaces or centre at all times. This was seen with Guardiola’s FC Barcelona, where Xavi and Andrés Iniesta hardly left the middle due to Guardiola’s obsession with having a numerical advantage in the centre. With this particular team, Guardiola has afforded Silva and De Bruyne much more freedom in the second and third phases of possession than many coaches allow who implement positional play. This may be due to Guardiola having faith in his players to recognise spaces during the match and their ability to move around their opponents. Alternatively, it could also be due to Guardiola believing that his squad is versatile in that the wingers are also quite competent in the interior, therefore encouraging such freedom will lead to more productive attacks. Either way, it is a departure from the systems of Guardiola past, and it resembles just one part of his evolution that has occurred since his arrival in England.

On the subject of wide interactions, the wingers remain close to the touchline in most moments of play during build-up and attack construction. This creates space for the no. 8s to move into for the attack, allowing them to both receive and move into gaps between the lines. Due to their half-space presence, the centre is left occupied almost solely by the centre-forward. The centre-forward will often check into midfield to receive the ball, seldom followed by the centre-back marking him. Once received, Agüero has a higher propensity to want to dribble by opponents before combining via a 1-2 to move up. Jesus is more likely to lay the ball off into the feet into De Bruyne or Silva, with his subsequent movements opening up his body shape to anticipate an additional through ball from them.

When it comes to solving the distance issue that came up with the 3-1-4-2, the full-backs are closer to the defenders during build-up, allowing for more stable circulation. Rather than forcing passes up the field into congested wings where the wing-backs previously were, their deeper position forces the opponents to move up their lines in order to close down. This inevitably frees up room for Silva and De Bruyne, alongside the wingers, who now provide the width. Previously, as many as four players occupied the same horizontal line at a given moment of play, leading to the distance issue. In the new system, players are much more balanced in their spacing as a result of their staggering. This causes opponents to be responsible for defending a larger area of space than previously, because of the nature in which City are spread out.

As a part of Guardiola’s positional play, there is often rotation between positions to try and unbalance the opposition. This rotation can take place horizontally, as shown with the castling of De Bruyne going out to the right and Sterling taking the Belgian’s place inside. In addition, there can also be movement vertically. For instance, if Bernardo Silva on the right-hand side comes deep to get the ball, Walker will take his spot and be the temporary right-winger.

There are, of course, limitations to how much rotation takes place in the team in the name of stability. Despite all the movements that take place, the same positional template must exist in all phases of the build-up before entering the final third. However, this Manchester City team are afforded a good deal of freedom for how they position themselves, as long as they remain within the confines of the system.

Moving up the pitch

Within the structure of how City are designed comes the functionality of how it looks on the pitch. The close interconnections between positions are manifested in the flow of the match via the constant providing of diagonal passing options of all lengths. Whether the Citizens are aiming to consolidate their possession and restructure or change their pace for chance creation, most of the passes played are diagonal. Diagonal passes elicit more of a response from the opponents when it comes to shifting, as they must change their reference point both horizontally and vertically. Square or straight passes do not require such shifting for the opposite reason. Therefore, a fundamental component as to why City are able to move around their opponents so easily is because of these diagonal passes.

Most teams in the Premier League prefer to cover the passing options behind them rather than apply pressure to the ball carrier in defence. In the context of attack development for City, this means that they are able to waltz up to an area around the halfway line oftentimes without any legitimate pressure applied to them. Therefore, the main methods of City move the ball into areas where they can create chances involved beating defensive schemes aiming to stay tight and compact between midfield and the defence.

The headliners for breaking down English midfields this season are the tandem of Silva and De Bruyne. With a mixture of intelligence, craftiness, and strength, the two of them have been lighting up the league this season for creating opportunities for their team-mates. Between the two of them, they have a total of 22 assists at the time of publication. While their skills on the ball are, of course, a factor in their impressive seasons, an equally key reason for both of their successes this season is their shrewd usage of blindside movements to freeing up space for themselves.

Silva will use the blindside to move into narrow channels in wide positions where he can more easily play with the left-winger to go up the pitch into chance creation. These situations allow Silva to deploy his skills in tight areas to cleverly combine and link with Sané or whoever may be on the left side. On the other hand, De Bruyne will often lurk in the half-spaces or the top of the penalty area, using his inactivity as a means of creating space for himself. Since other defenders on the pitch are shifting in response to the ball changing points, spatial dynamics change as a result. De Bruyne will then show good patience to wait for the pass as it arrives from an improbable source, using the newfound space to dribble into or thread through balls in behind onto oncoming runners.

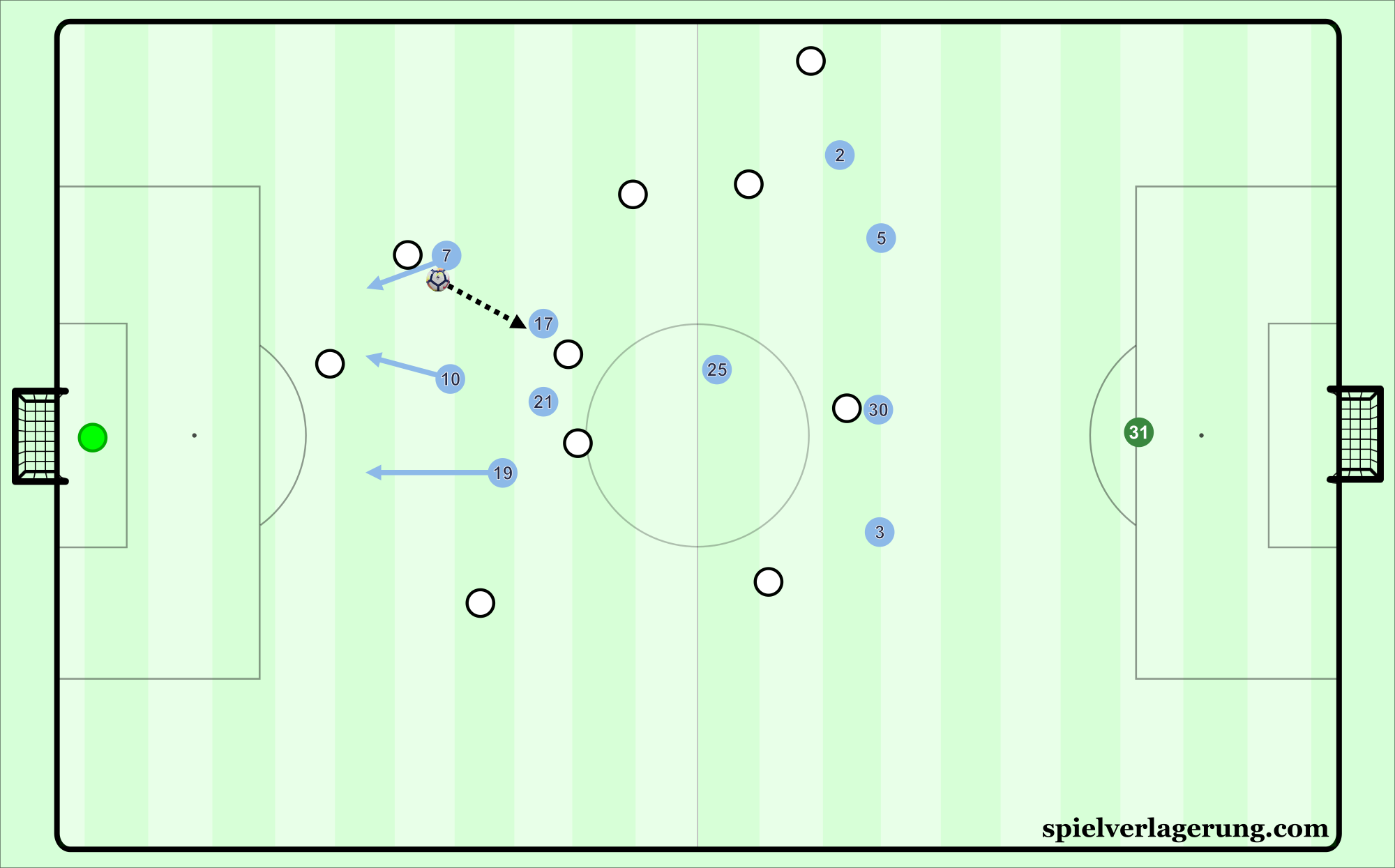

De Bruyne’s positioning in the half-space allows him to receive diagonal passes to unbalance defences from deep. Prior to receiving the ball, he was patiently walking, waiting for the opponent to turn his back to him before taking steps to the position seen above. In this particular sequence, the defence collapses on him and he is able to combine with Jesus before scoring.

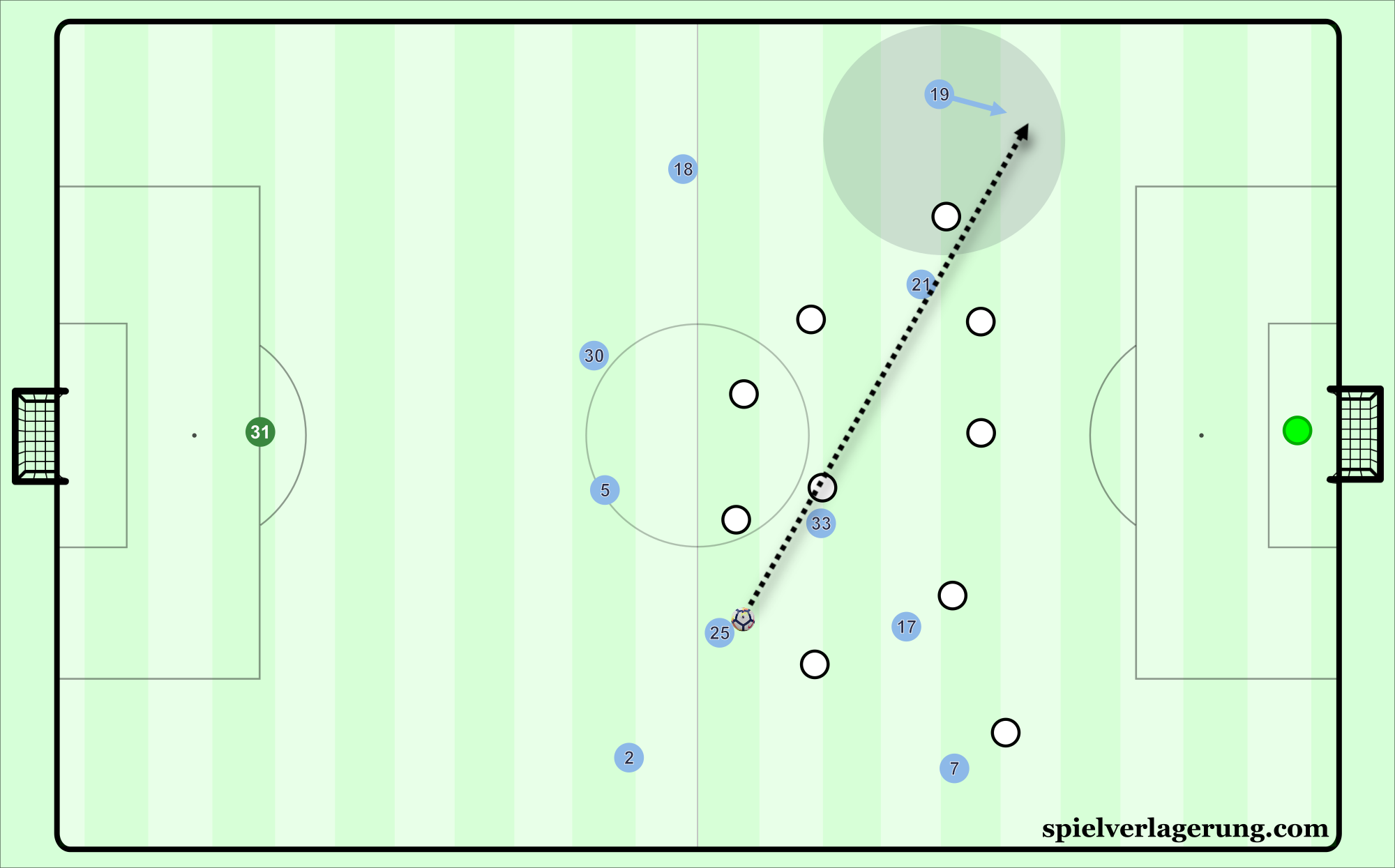

A frequent manner in which City progress up the field takes advantage of the quality found in on the wings. Teams in England are often focused on covering the options immediately close to the ball, preventing passes that are on the same side of play. For instance, when a team build up on the left side, the defence will be mainly concerned with that side, and the players far away from the ball will not often contribute to defending either the centre or possible solutions out of that side.

To capitalise on this, City frequently bypass the covering scheme of their opponents and enter the final third by playing aerial diagonal balls into the wingers. When these passes are played, Sané and Sterling are isolated due to the opponents being overly fixated on the close passing options. To signal to their team-mates that they would like these passes, Sané and Sterling simply raise their hand up from a distance. When the signal is picked up, the pass is played. When these passes are completed, Sané and Sterling frequently have a lot of space for dribbling by the player defending, and City move into chance creation mode. These aerial switches across the pitch are an effective way of evading the opponents’ defence, simultaneously exploiting on the individual gifts of the team.

After seeing Sané raising his hand across the pitch, Fernandinho drives the pass in the air towards Sané. Once the German receives, he has room to dribble and take on the opposition right-back.

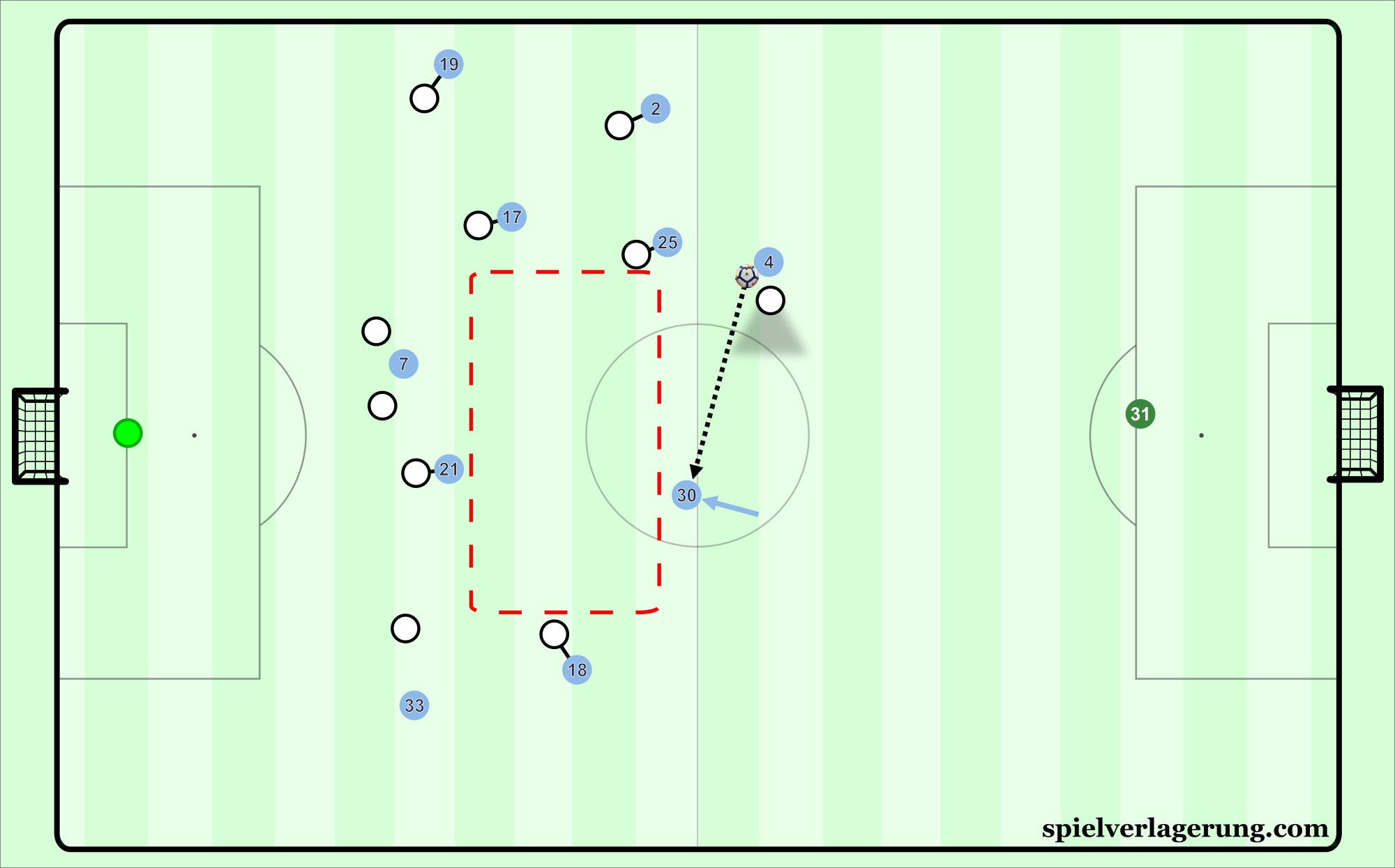

Since English teams often are more concerned with covering than applying pressure to the ball, the centre-backs for City are frequently afforded a plethora of time on the ball to make decisions. It is not uncommon to see a defender for City to dribble forward without much pressure applied at all. However, not every opponent has allowed City to have such a luxury. For example, Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli pressed high up the pitch and hoped to stifle their build-up from the onset. José Mourinho’s Manchester United wanted City to exclusively play out of their right side, by forcing the ball towards Kompany, who was less technically proficient than his partner Otamendi on the day.

Guardiola has coached into his squad the recognition of finding the right moments for his defenders to step up into the ball to move the ball forward. As a part of most pressing schemes, teams will block passing lanes to players through using players’ body orientation, also called a cover shadow. Similar to how Silva and De Bruyne use the blindside to create space for themselves, City’s centre-backs now recognise moments in the play during which they can step up and join the attack through blindside movements. When opponents attempt to block them off via a cover shadow, they will simply step up into the next line when it is open and present themselves as a viable option. When they step up into such spaces, there is typically room to dribble, so City will progress up the pitch thanks to this movement.

This opponent aimed to corner Kompany by limiting his passing options using his cover shadow. Otamendi recognises this and steps in front of Kompany to receive the ball. Thanks to the opponents’ man-orientations, Otamendi has plenty of room to dribble forward and advance the ball.

Guardiola has put together a myriad of options that City can deploy when constructing their attacks. Thanks to their positional structure and the qualities of their players, they can aim to break down teams that set up in variety of ways. The multi-dimensionality of City’s build-up makes them difficult to prepare for, and even harder to keep from going to goal.

Ederson Scholes de Moraes

Of course, that is not his real name, as he is actually named Ederson Santana de Moraes. However, it would be impossible not to discuss the impact and versatility that the Brazilian goalkeeper brings to the blue side of Manchester. His ability of a shot-stopper has been proven to be superior to Claudio Bravo’s, with City only conceding 20 goals on the season at the time of publication. Of course, this is also to the array of improvements on the defensive side of play, but the 24-year-old also has demonstrated a higher level of consistency as a goalkeeper this season that Bravo.

The improvement that Ederson brings to City as a team is not just defensive however. If anything, he is a huge asset in possession as well. With Bravo in goal, the Chilean has some of the best feet in the world when it comes to short- and medium-range distribution. For teams that high press the Citizens, this is a huge asset in build-up. The goalkeeper offers an extra man and allows for circulation to take place in deeper areas. When teams go and pressure the goalkeeper or centre-backs that are in line with the goalkeeper, spaces will open up high up the pitch. These spaces are where City, alongside many other teams, are trying to target with their play.

Ederson is competent in his short- and medium-length passing, sometimes struggling when it comes to playing passes on the first touch into tight areas. However, Ederson has an edge over Bravo, and every other goalkeeper in the world, in long-range distribution. Due to freakish leg strength mixed with excellent technique, Ederson can laser passes from dead balls that range up to near the opposition’s penalty area in a truly special way. These passes have excellent accuracy that find their intended target at a high frequency. For a lack of a better comparison, he is the Paul Scholes of goalkeepers, with an equal propensity for physical play on the defensive side of the game.

Consequently, City have a higher versatility when it comes to ways that they can break through opponents from their deep build-up, particularly against opponents who employ a high press. As mentioned earlier, most domestic opponents tend to drop off versus Manchester City, not challenging in the first phase of possession. For those that wish to engage them during goal kicks, Ederson expands the possible solutions with his passing range.

If an opponent steps up towards the centre-backs and crowds the first third of the pitch, Ederson introduces the capability of beating pressing schemes by playing over them and avoiding them entirely. Since a player cannot be offside on a goal kick, City’s attacking players will move goal-bound if the opponents step up to pressure. Ederson can then find them on the aerial pass with remarkable timing, bypassing the opposition press and playing over the majority of the opponents with one pass. These passes will put City into situations that are advantageous for chance creation, as either they are right near the opponents’ goal or they will have equal numbers and an advantage due to attacking talent and speed edges.

As Ederson places the ball down for a goal-kick, the opponents move up to high pressure City, expecting them to play short. Sensing this, the front three players of City move up, knowing Ederson can reach them and that they cannot be offside on a goal kick. A large gap is created centrally, and Ederson spectacularly plays it to Sterling.

When opponents begin to anticipate this, large gaps between the opposition players will form centrally around the centre circle, providing space for City players to move into as well in order to break the press. Ederson is more than capable of playing chipped passes that find the option in this area, giving City yet another option of how they can evade high pressing opponents. When City faced Tottenham at the Ethiad, Mauricio Pochettino’s high press was evaded due to Ederson’s passing range, and even created a series of dangerous attacks from his own penalty area. The addition of Ederson to Guardiola’s team has made City the most resistant team to high pressing in the world at the moment, as when combined with the quality of players in the back and his long passing range, a plethora of options exist how to beat high pressing.

Finishing and low crosses

As the saying goes, there is more than one way to skin a cat. City are versatile when it comes to finishing what they created by building up and moving the ball up the field. They can pass through the vertical gaps, play the diagonal ball from the outside behind the back line, use set-pieces or counter-attack like there is no tomorrow. Nothing is surprising about the fact a top-team like City with high-level midfielders and forwards can do it all.

What has stuck out this season is how they have made use of low crosses. Using the wings may not be something that comes immediately to mind when thinking about a Guardiola side, but he knows how to use his attacking players. Just like he let Franck Ribéry and Arjen Robben do their thing back at Bayern Munich, he utilises the fast-paced Sané and the dynamic Sterling. Several goals have been scored after City broke through to the touchline and crossed the ball low into the centre. Sometimes the assist had the typical attributes of a cross, which means it was a rather lateral ball. Sometimes the assist was rather played like a backwards pass. Sometimes both were combined; just watch their third goal against Stoke City.

While the usual high cross has a low chance of being converted, and that number should be even lower when your target players inside the box are not known for being forces in the air, the low cross gives the passing player a higher degree of control and accuracy, while it is also typically faster than the high cross and, therefore, harder to defend.

What is needed to be able to play a low cross is dynamic and usually a bit of an opening. The opening can be created by long diagonal switch passes, for which Sané has been the receiver frequently in the past few months. On occasions, it even appeared that City focussed on Sané dribbles too strongly, as they tried to target him repeatedly. Sané’s wide position outside the block and his limited defensive responsibilities allowed the German to receive plenty of passes and start his dribbles, but even he cannot always deliver.

Another setup for the low cross has usually been the half-space run by one of the full-backs. Particularly on the right side, where De Bruyne often is found wide as the Belgian drifts to the touchline and takes on the opposing full-backs, Walker has the chance to travel through the inside lane and receive the ball in the back of the defender. When Walker did not make the run or was not in position fast enough in some of the matches, De Bruyne sometimes just punted the ball into the box. That also happened occasionally after longer possession spells without any substantial progress. Dynamic is needed to create the right environment for the breakthrough and the low cross.

Pressing

An underrated aspect of City’s success concerns their effectiveness in pressing. Per the Expected Goal Model (xG) provided by Understat, City allowed a xG value of 14.79 and conceded 13 goals over the course of 22 league matches, which highlights that Guardiola’s player have not significantly over-performed defensively. The fact they are so hard to break down is the result of a developmental process.

Early approach and issues

When the season started, City were not looking like an unconquerable stronghold. The pressing scheme was man-oriented, the intensity not quite on the level they needed it to be. City usually used their 4-3-3 shape also when defending against a team who employed three players in the first phase of build-up, as Guardiola’s player could just force one-on-ones across the field. The first line of pressing tried to work aggressively and block the lanes, while there was no deliberate intention to force turnovers early on. Interestingly, in the first phase of City’s pressing, the midfield and back line narrowed down the space in between, while it was not unusual to discover a larger real estate between midfield and attackers line.

When the opponents were able to bypass City’s first line, it triggered the first transformation of City’s pressing structure, as the two advanced midfielders—sometimes even Fernandinho—jumped forward and compressed the space. Since the back line was steadily moving backwards, the area behind De Bruyne and Silva was growing. Especially within the first few yards behind the halfway line, City intended to interrupt any passing flow and stop the progress of the opposing play. Since City often missed the opportunity to guide the build-up towards the touchline, they remained reactive and, therefore, could not always prevent every pass into the space behind the midfielders which then often caused danger for their own goal.

Usually the pass behind Agüero or Jesus triggered the first transformation, as the three midfielders advanced to attack the receiver or to transition into a man-marking scheme. Around the halfway line, City pushed the two lines together, while the ball-near full-back moved forward. (GIF)

Deeper into the season, City started using curve-runs up front more frequently in order to set up pressing trap. If they are not able to successfully force the early turnover, City typically transition into a 4-1-5, with the two wingers dropping back on the outside lanes to potentially have double coverage there. The third phase of pressing sees them in a 4-5-1, as the two centre-midfielders move back and join Fernandinho to close down the middle. (GIF)

High-quality teams, who are typically keen to exploit the zones between the lines instead of just moving the ball around the block, were able to make use of City’s slight weaknesses. What can be associated with Guardiola’s coaching work is that his players improved their decision-making over the course of the past months. The amount of mistakes committed in terms of positioning has declined. Early on, however, City players showed the tendency of moving into the wrong zones or towards the wrong opponents at the wrong time, which the example in the graphic below illustrates.

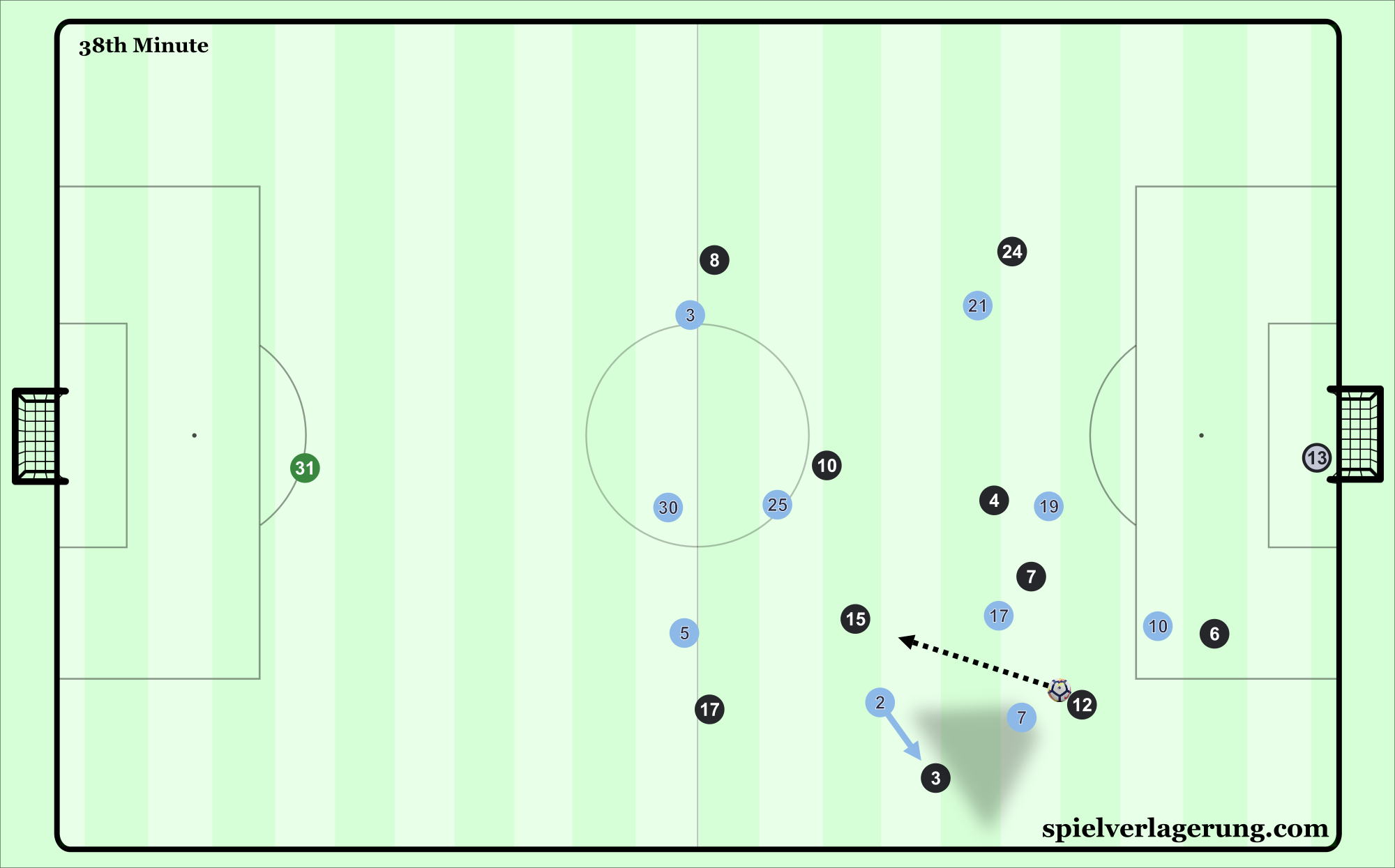

During their first match against Crystal Palace, that situation occurred. Even though Sterling made the right move and put Patrick van Aanholt (#3) in his cover shadow, Walker decided to go wide instead of threatening Jeffrey Schlupp (#15). Those mistakes became rare as the season went on.

In addition to that, the centre-backs strictly stuck to man-marking in some of the earlier matches which, considering the general high line City employed due to the long spells of possession, made them more prone to being pulled away and caught out of position. Fernandinho was able to smooth some of these situations out, but that caused him to be less present in the no. 6 space which meant less protection for De Bruyne and Silva. With the false full-back becoming a crucial part of City’s macro-tactical concept, the additional protection at the back or in the zone ahead of the centre-backs due to the addition of another player worked wonders. At first though, mainly the individual quality of Guardiola’s helped to prevent the opponents from advancing into City’s defensive third more often, where even the best defenders can never win every duel, especially when they have to be reactive and sometimes have a speed disadvantage.

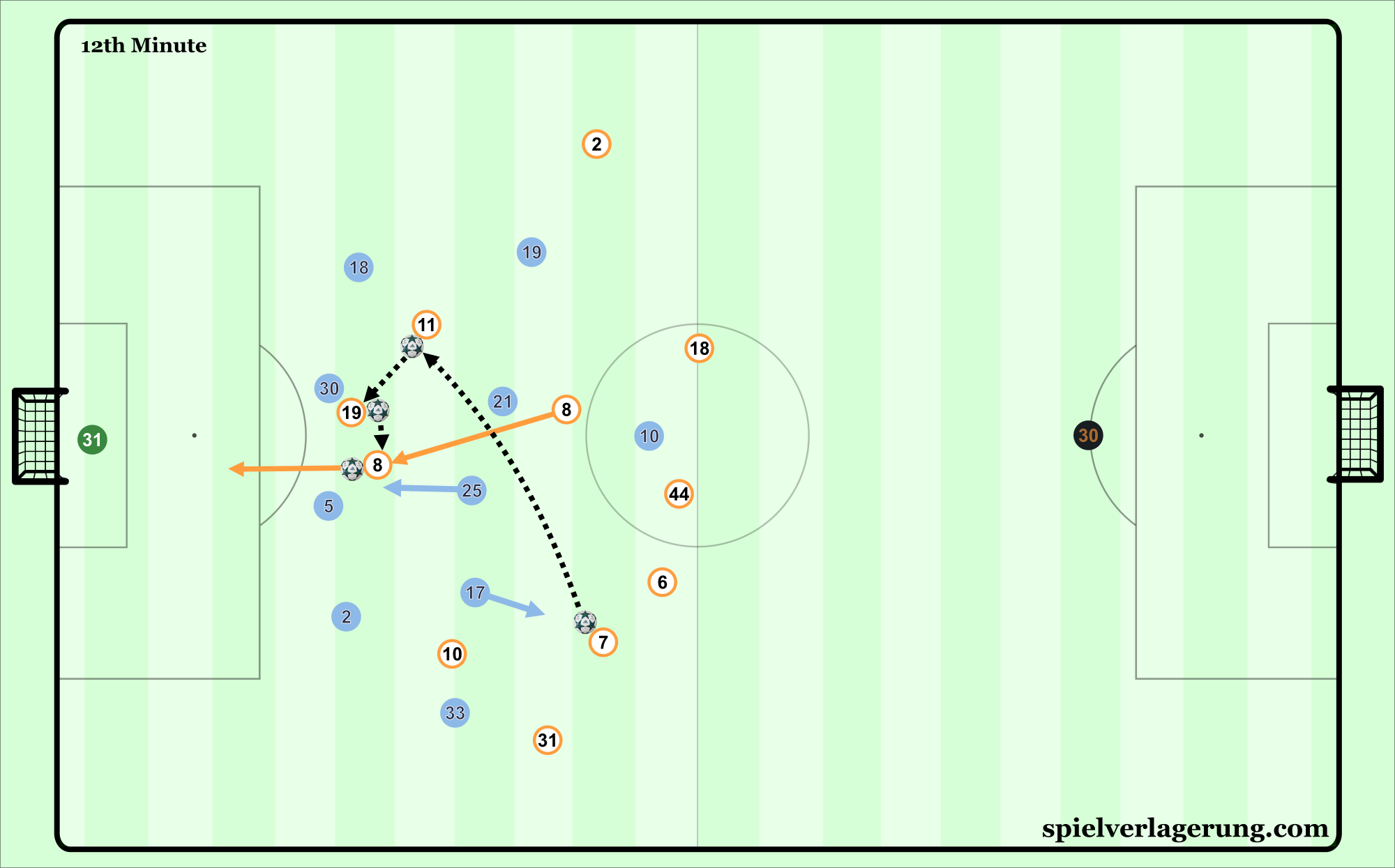

As pointed out above, City usually deploy a 4-5-1 in the third phase of pressing. The issue can be that they hold back and remain passive with the intention to just block the zones of importance. Without any pressure put on the ball carrier, it can lead to situations like that one, in which Taison (#7) broke the line while Fred (#8) escaped Silva and was only stopped by a tremendous Fernandinho tackle.

City did still not allow comparatively much in their defensive third during the first quarter of the Premier League season and continued to do so after the end of October. In the first ten matches, City’s opponents were able to complete 2.3 passes (without crosses) within 20 yards of the Citizens’ goal. The number even dropped to 1.7 in the second ten match span. Not one other Premier League team came even close to that.

Increase of proactiveness

Over time, City have become far more versatile in how they set up their pressing. A striking example was their home match against Shakhtar in late-September, in which instead of employing the typical centre-forward-vs-centre-back setup, City made use of the two wingers to make curve-runs towards the two Donezk defenders in the middle. Coupled with positioning De Bruyne or Silva higher in the middle and putting immediate pressure on the centre-midfielders after or even before receiving the ball, it created either an effective trap when they allowed the ball to be moved into the centre or a tool to force errors and early turnovers when all the passing options were shut down, and only the risky pass towards the wing became the last alternative for Shakhtar’s build-up players.

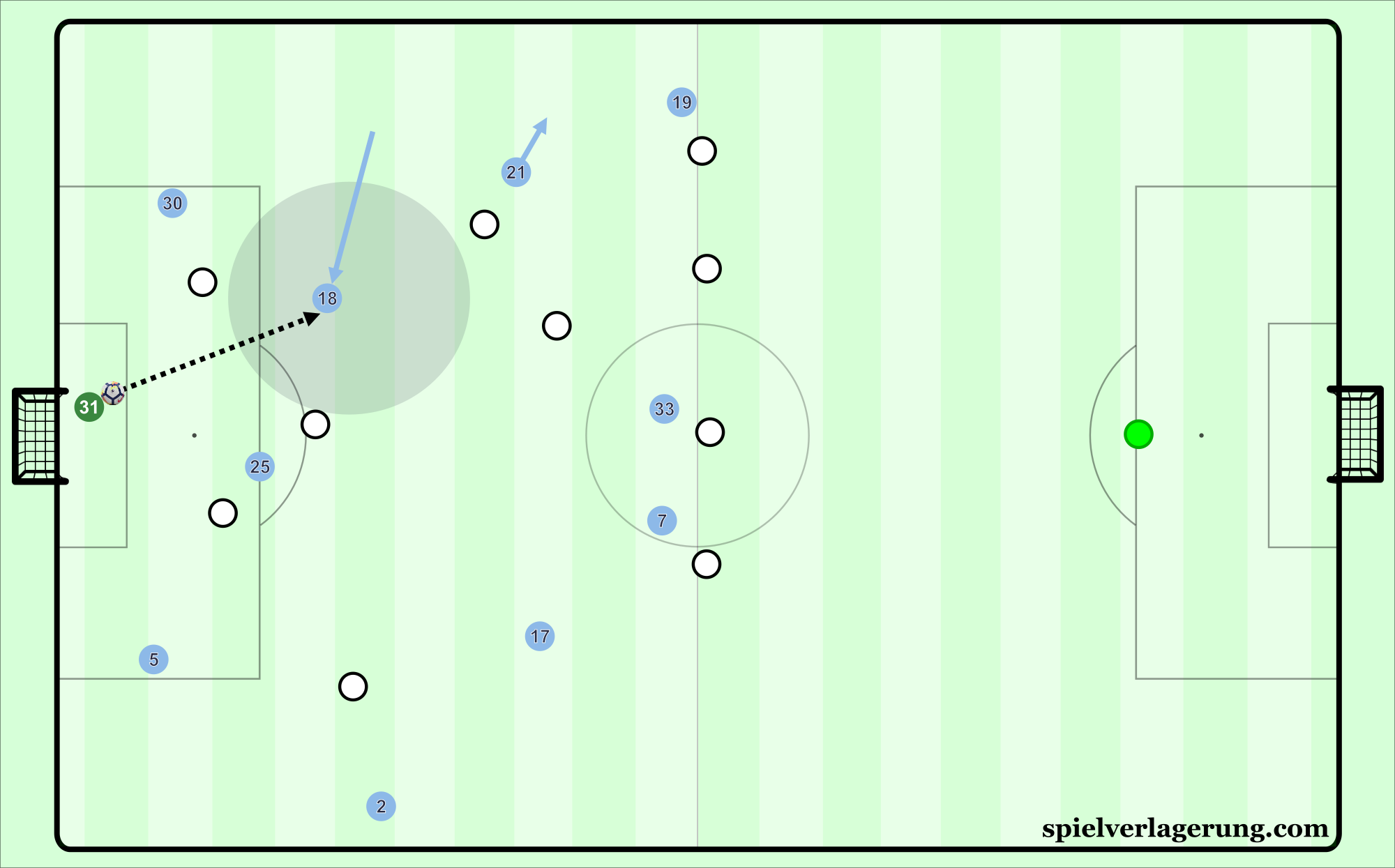

There was not much Ivan Ordets (#18) could have done differently, since he apparently did not want to just punt the ball forward and cause a transition attack through the middle. City left one lane open, which is something pressing specialists such as Atlético perfected in the past. Jesus was probably not even visible as he hid behind Fred. He could not control the ball, but it nevertheless shows how City can utilise these traps with their high press.

City, however, did not become impetuous due to the increased intensity in the first phase of pressing. Guardiola’s players understood how and when to end their high press in order to fall back and produce enough compactness around and behind the halfway line. The second phase of pressing was again focussed on stability and the prevention of passes through the half-spaces or the middle of the field. The two centre-midfielders, in particular, had to prove how they have an understanding of transitioning from a high to a midfield press. Since the two often stood alongside or close behind Agüero high up the pitch, it would have been easy to be caught up in the situation and suffer from tunnel view, determined to produce the early turnover. Giving up the high press and falling back into a more compact shape to contain the opponents who just outplayed you requires a high football IQ, and, of course, the right coaching.

Another key role in City’s pressing and the effectiveness of it play the two full-backs. Both are asked to move up the field and block the opponents on the wing repeatedly, for which they not only need the timing and stamina, but also the feeling for how to use body postures in order to prevent the opponents from bypassing them. Both Delph and Walker have proven they can provide just that over and over again. Usually, the two full-backs start from a position similar to the one Fernandinho typically has, as far as height on the pitch is concerned. They either start to make the run once one of the opposing wingers or full-backs receives the ball, notably when the opponents position themselves relatively deep, or they begin to advance when the opponent is about to move the ball to one side, which gives City’s full-backs the chance to lure them into playing towards the touchline although they are right in front of the receiver when the ball arrives.

Since City’s centre-backs acted less man-oriented as the season went on—and often had to defend against a lone striker anyway—they usually pushed towards the half-spaces when one of the attacking players moved behind the full-back and offered the option to play a long-line pass and exploit the open field. Fernandinho usually dropped back and took over the initial zone the centre-back was assigned to cover. There have been only a few examples when City did not use their full-backs in that kind of aggressive role; one was in their 2-1 win over Napoli in mid-October. In that match, Walker und Delph apparently had the job to mark the two advanced wingers instead of pressuring the full-backs. Surely, it had something to do with the quality of Lorenzo Insigne and José Callejón, and the respect City had to show them, but it also brings up an interesting question: why do not more teams use wide wingers high up the field to tie up City’s full-backs?

Walker and Delph are a crucial part of City’s high press and the way they can shut down opponents. In the Napoli match, however, they were barely a factor in the early phase of pressing. Tieing them up would likely create space next to Fernandinho. While the Brazilian has a high defensive range, he could never cover a real estate as wide as 30 or so yards at once. It might force Silva and De Bruyne to drop back, which would then decrease the intensity of the high press. Or there would be an opening to exploit and enter the middle third. But since only a few teams have even attempted to use high wingers against City strategically, we probably have to wait for the Champions League knockout stage to find an answer to how Guardiola would react and adjust the pressing scheme.

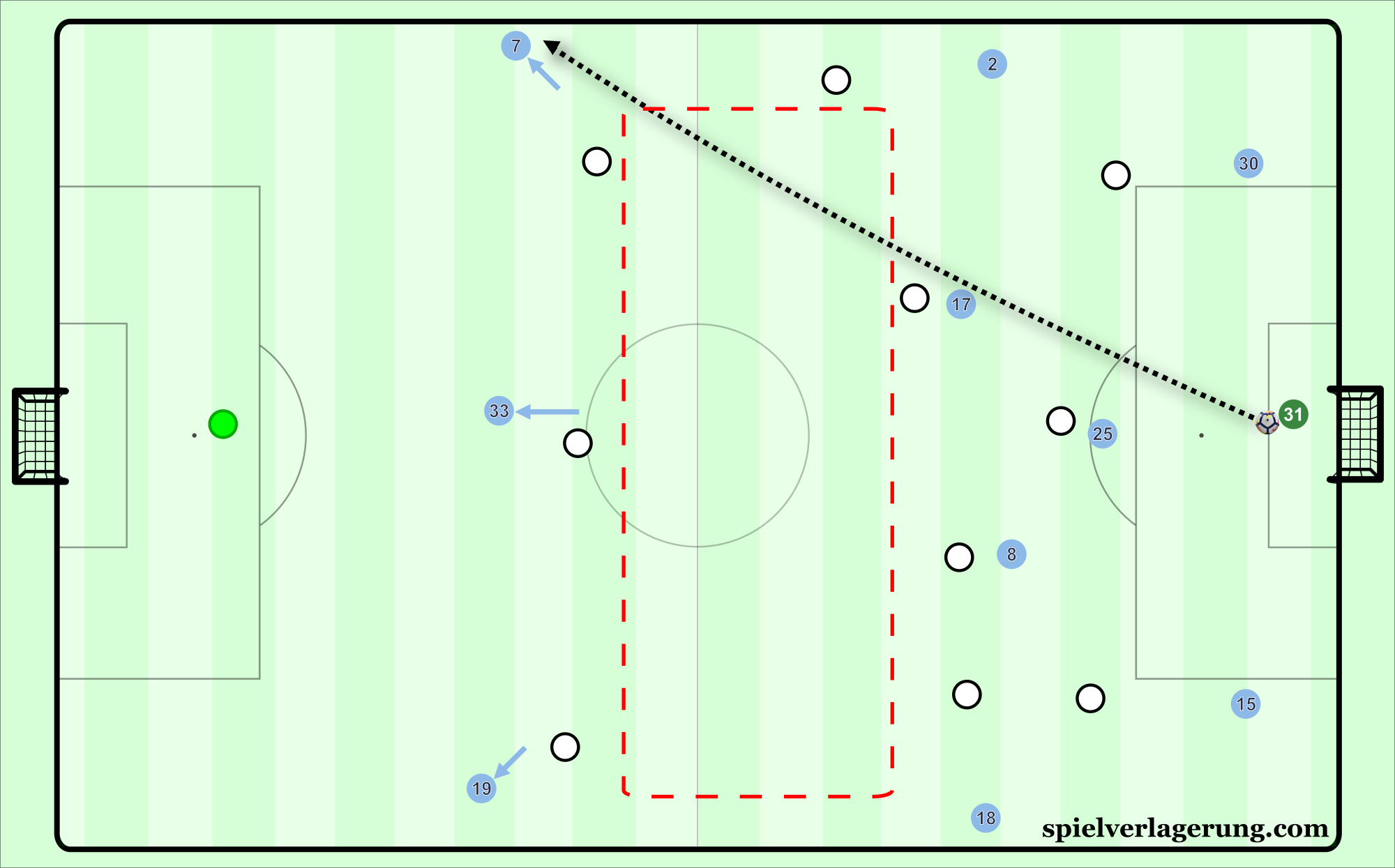

These typical three-point build-up plays can be shut down fairly easily. Positioning two wingers high up the pitch may force the City full-backs to hold back. But there is probably a downside to that. In order to use two wingers and keep the centre-midfielders busy, the City opponents have to rely on two build-up players at the back, which would create more distance for lateral passes. And as Domenico Tedesco recently pointed out in an interview he gave us, the ball is loose for a moment which is the best time to pressure. (GIF)

Defensive and attacking transitions

The times in which City have either just lost or recovered possession define their style of play as much as their moments in possession. These transitional moments and City’s fast reactions as a team to the changes in the game are just one of the many ways that Guardiola’s side distinguish themselves at the top of English football. While many goals have been scored through counter-attacks this season, their approach to defending counter-attacks and chasing the ball after losing possession sets them apart from the rest of England.

Counter-pressing

While a sophisticated possession style, particularly on the Guardiola level, typically minimises the threat of being hurt by transition attacks, there will remain a slight vulnerability that even the best counter-pressing would never fully solve. As Dewar and Thompson showed in their analysis on Statsbomb, ten per cent of the final third entries that City allowed came from fast transition, as of November 22, with fast transitions defined as a possession sequence that starts in a team’s defensive third and ends within 15 seconds or fewer in the opposition third.

Just like in the pressing department, City needed a few matches to find their groove and establish a forceful counter-press. At first, a mix of mediocre decision-making and lack of compactness between midfield and attackers line hindered them from regaining possession quickly. Two important factors have changed that: first, City have become more dominant in the early phases of their matches which has enabled them to pin down their opponents beyond the halfway line or even in the final third which has naturally made their counter-pressing more effective. Second, the sophisticated use of a false full-back has helped to switch from a 4-3 shape behind the three forwards to a 2-2-3 shape, allowing the two advanced midfielders to have a higher position in general, without having to be concerned about the space behind them. It has also given the two midfielders the option to attack one half-space collectively, thus using more pressure to interrupt transition attacks or having a better chance to react to overloads.

Moreover, City’s shape has gained horizontal compactness with the two wingers—or at least Sané on the left—providing width while the full-backs can drift towards the centre regularly. In addition to the group-tactical dynamic produced by the likes of De Bruyne, Silva or Gündoğan who collaborate almost perfectly when they have to secure the rebound or switch from attacking to defending mode, the shorter distance between midfield and attackers line is the main reason the backwards pressing by the three City forwards is more fruitful than in the first part of the season.

This is how it should not be done. Instead of preparing a potential counter-press before Sterling received the ball, City just let their winger be trapped within a pack of Crystal Palace players which then ultimately led to a dangerous counter-attack, because the half-space was not protected. (GIF)

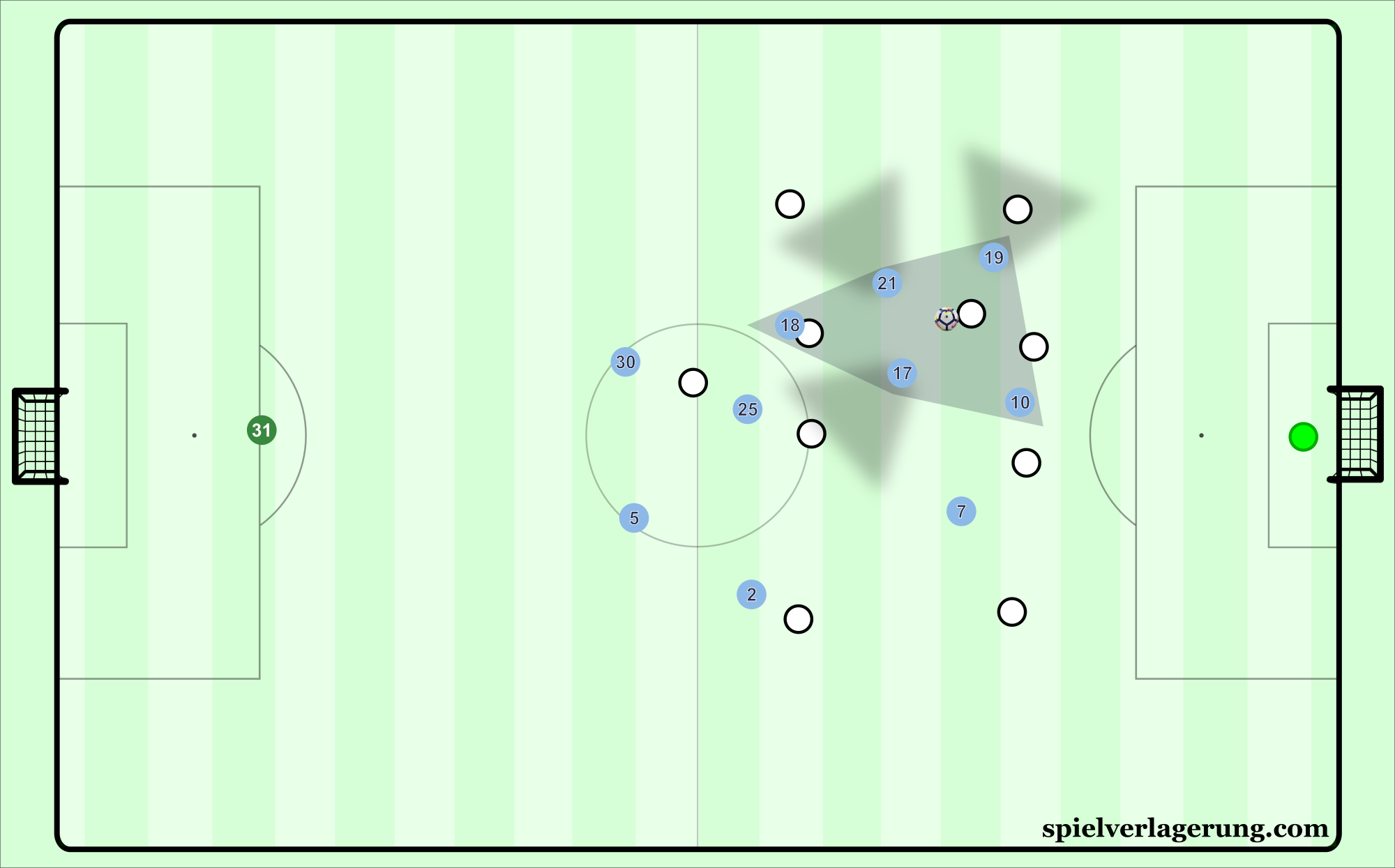

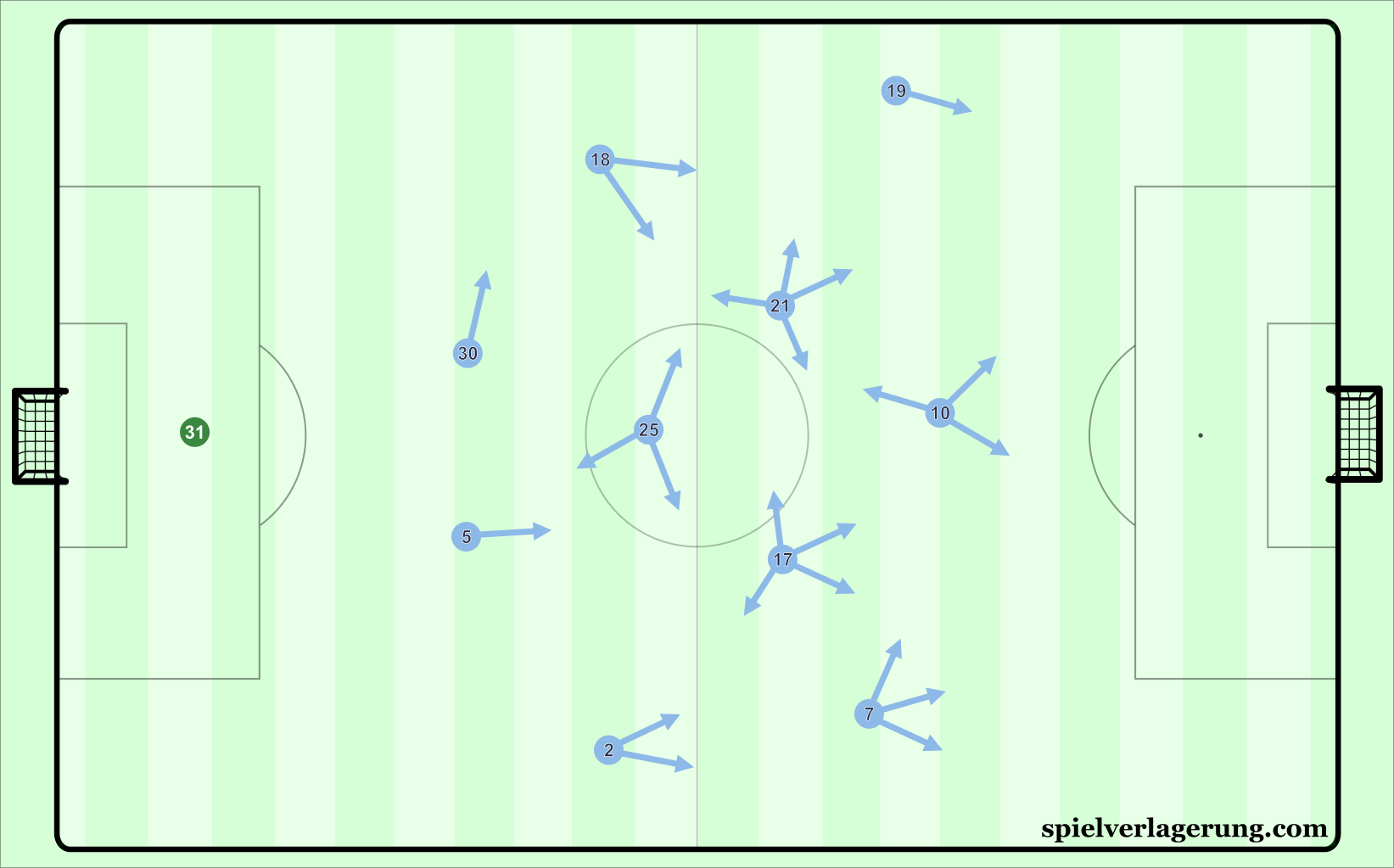

This is how City often set up their counter-press these days. Because the inverted full-back provides more protection in the no. 6 space and the two advanced midfielder can drift laterally more freely, City create plenty of pressure around the ball carrier who intends to trigger the transition attack.

Early on, City occasionally struggled to regain possession as quickly as intended. The two midfielders forced isolated duels, while backwards pressing seemed far from impactful. Too often, the ball-near forward was on the wrong side of the ball carrier and just hastily attempted to pressure the opponent, with his team-mate in front of the ball not knowing how to read what the forward tried to do. What City helped to avoid any destabilisation due to said issues in regards to compactness and coordination was smart damage control. They always switched from counter-pressing to pressing within a short time frame. Instead of not letting it go and keeping the counter-pressing setup, they usually quickly transitioned into the 4-1-4-1 midfield press.

Previous Guardiola sides have had the seconds after losing possession be key hallmarks of their game model. The most famous of which was the “Six Second Rule” utilised at Barcelona, which established that possession should be regained within that time frame. At Manchester City, Guardiola has instilled counter-pressing focused on eliminating the passing options for the player in possession in the shortest amount of time possible.

After having lost the ball to Bournemouth, City tried to immediately win it back, although they did not have enough presence around Andrew Surman (#6) who played the lateral pass to avoid the turnover. City did not go for another attempt but transitioned into their usual pressing formation to utilise the practised schemes. (GIF)

Rest-defence and reorganisation

Another key component of how City defend transitions comes in the form of their rest-defence, also referred to as “Restverteidigung” by our German colleagues. Rest-defence refers to how a team’s attacking shape by the “rest of the players”—mainly those not involved in the attack—assists in defence. The name may suggest otherwise, but the players participating in rest-defence are not necessarily resting. This concept illustrates how the structures between attacking and defence are symbiotic. In order to prevent harmful counter-attacks, Guardiola organises his team in possession so that when possession is lost, they are adequately balanced to deal with transitions that happen to break through the initial counter-press.

During City’s possession and chance creation, they are organised so that they have a one person advantage in the back to provide extra security against any balls over the top or cover if the first defender is dribbled past. If there are two strikers up high, City will keep three behind the ball providing cover. When three are held up, four will stay behind, and so on. When the two centre-backs are in need of support, it comes from the far side full-back most often. For instance, if City are attacking down the left side of the pitch, Walker will help cover for the centre-backs. Fernandinho will reside in front of the first line of defence preventing anything down the middle, with a distance occupied that can have him move into a covering spot if needed.

City’s organisation of their rest-defence is similar to their attack, in that they value outnumbering the opponent in the centre at all costs. By putting these players centrally, the only option for effective counter-attacking for the opponents is by going around them. When outnumbered, City will be able to apply pressure with more than one person and easily win the ball back given the athleticism and abilities of their defenders individually. If a team cannot play an attacking option into feet centrally, then they must play into space in order to have a shot at catching the Citizens on the break. Unfortunately, with City’s high line, the weight and timing of the pass and the run have to be spot on. If it is not, either the pass is too meek and it can be intercepted, or the pass is too long so that it runs out of range of the forward and the ball is collected by Ederson. Therefore, counter-attacking through the centre is extremely difficult due to City’s rest-defence.

After the opponent intercepts Silva’s pass, City are secure for defending counter-attacks in the centre thanks to the 5v2 advantage in their rest-defence, while also being able to pick up any runners from the opponents.

However, going through wide areas isn’t an easy task either, as it lacks the immediate threat that countering through the centre does thanks to the increased distance from the goal, alongside the lack of sufficient angles for playmaking. When forced to the touchline, the playing angle for the player on the ball decreases by 180 degrees, as turning away from the play will lead the player to go out of bounds. This essentially compels players to have no choice but try and dribble past City players as a means of counter-attacking, a tactic which has not proven successful due to City’s excellent ability to both recover and apply pressure as a team.

However, especially against top opponents, City have been forced to quickly transition into defence in their defensive third of the pitch. During situations where players are running towards City’s goal and an immediate threat is present, the back four of City collapse centrally and get ultra-compact at the top of the penalty area. Between the right and left full-backs, there can be no more than ten yards at times. Similar to the logic behind their rest-defence, such a scheme forces any passes to be played around them.

City’s back four quickly pinch together at the top of penalty area during their opponents’ counter-attack, leaving the striker offside. Due to the congestion of bodies around the ball, shots from distance are blocked, and the only open option is wide, which presents much less danger than anything central.

This makes it so any shot that is taken by a player in the centre is likely blocked by one of the four defenders. Any passes that are played into team-mates in the half-spaces can have pressure applied by one of the defenders, and any shot they take comes from a less probable angle of scoring than the central one. The immediate priority is delaying the opponent from shooting and having the midfield recover. The next aim is to back-press and win possession, or to coerce the next pass to be played backwards, during that time City step their lines up and move into their standard defensive shape.

Attacking transitions

Equally of note is City’s approach to attacking transitions under Guardiola. Early on in his career, Guardiola sparingly had his teams counter attack, preferring to use the transition period to have his team get organised into their attack structure. Nowadays, his team are one of the most effective sides on the counter in Europe. With players such as Sané and Sterling in the team, it would be foolish not to use their speed in transition.

Rather than aiming to counter whenever possible, City wisely pick their moments to unleash their weapons when their opponents are spread out during their attack. In most attacking shapes throughout the Premier League, the midfield and attack are spread out in an effort to create as much space as possible for every player. Conversely, this means when City win the ball, their opponents have a large amount of space to make up in order to apply pressure to the ball or recover into their defensive position. The moments when the Citizens recover possession then offer the most amount of space as a result.

Having a large amount of space available to attack means little if the players on the pitch do not recognise it and act quickly. City understand this notion during their play, which explains their remarkably fast reactions when moving from one phase to the other. When the ball is won and there is a strong counter-attacking opportunity, the attacking players immediately start their runs towards goal, running at full speed towards their destination. The opposition often take a fraction of a second longer to react to these changes, during which City’s starlets have already taken off and difficult to catch up too.

After regaining possession here, the trio of Sané, Agüero, and Sterling quickly move forward once they recognise how opened up their opponents are.

By this point, City’s attackers have plenty of space to receive the ball on the run. The ball has not been played yet though and is most often in the midfield at this point. Considering the angles of the runs and the time available to pick out the pass, the player on the ball is spoiled for choice. Regardless of the option he chooses, he has to weigh the pass just right so that the pass arrives to the targeted area when the player does.

These passes played lead the runner towards the goal, either centrally or from width. When played centrally, the pass typically goes in between the opposing centre-backs, often leading the striker right to the goal and a breakaway with the goalkeeper. If one of the other options is chosen, the pass sets up an opportunity from a low cross to be played across the goal mouth, leading to an easy finish when pulled off correctly.

In either case, City have their opponents on their heels. Due to the blistering speed of the attack and the supporting runners, there are at least three players joining for the counter-attack. In the instance that a player does not wish to shoot when close to the goal, they can play a pass and likely there will be someone there to finish a tap-in. Regardless of the outcome, the overall speed and quick reflexes of the Citizens places them as one of the top counter-attacking clubs in England. Many goals throughout the season have come from their attacking transitions, notably in their routs against Stoke, Liverpool, and Tottenham. It is yet another dimension in how City have decisively beat those who have come across them throughout the season.

Special role: The false full-back

With Mendy, Walker, and Danilo replacing the prior generation of City full-backs, it appeared in this year’s preseason that Guardiola would return to having his full-backs being high and wide in possession, similar to his Barcelona side from 2008-2012. However, Mendy suffered a torn ACL in a match against Crystal Palace that ruled him out for the next several months. From moments of crisis come opportunity, and Delph has taken advantage of this. In the span of a few months, he has risen up to become first-choice left-back through his consistent and added stability.

Rather than employing him as a traditional full-back/wing-back, Delph has most frequently been used as a false full-back. In the role of a false full-back, rather than primarily be positioned near the wing, the player will move towards the half-spaces and central areas of the field. This role increases the central presence during build-up and circulation, allowing other players to be moved higher up the pitch in possession. In addition, having this player located centrally in rest-defence bolsters defensive transition efforts. If opponents counter-attack at high speed, the space afforded to them is wide areas due to the congestion in the middle. This is less of an immediate threat than conceding space in the middle, which gives City more time to recover into their defensive shape in case their counter-pressure is broken.

During build-up near City’s goal, it allows for more accessible solutions to beat the opponents’ pressing schemes. For example, if Ederson has the ball, any player wishing to press him and simultaneously block off the centre with his cover shadow must account for two players instead of one. If there were no additional option centrally, eliminating Fernandinho would be much easier for the opponents. Ederson would be forced to play sideways and make build-up more wing-focused for City. Alternatively, the goalkeeper would play long and hope City win the aerial duel, an option that relies much more on luck than protecting the ball via stable possession.

With the false full-back moving centrally, the remaining defenders will adjust accordingly. Since the false full-back is most frequently from the left side, the left-sided centre-back—most often Otamendi, sometimes Eliaquim Mangala—will slide out towards the left more, stopping at about the width of the penalty area. The other central defender, whether it be Stones, Kompany, or another player, will slide centrally, while the right full-back will behave as a right-sided centre-back in a back three if needed. If the opponents are defending very deep, the other full-back will move up as well to prevent an excessive build-up of players in rest-defence.

As the opponents pressure high, Delph recognises the gap in the centre and abandons the traditional position of a full-back in favour of moving inside. Once Ederson plays him the pass, Silva moves to the touchline to free up space for Delph to dribble forward.

With Delph’s background as a centre-midfielder, Guardiola’s deployment of Delph is superb in its dual purpose. Moving Delph inside allows him to play a position and role familiar to him, assisting in build-up to give Fernandinho an additional player on the same line to help with circulation in the attacking half. This, in turn, eliminates the need for Silva and De Bruyne to come deep to receive the ball, and they can receive the ball more in the creative positions closer to the opposition goal. It also complicates the shifting of the opposition in defence, as the shorter horizontal passes during circulations force the opponents to make decisions about whether to cover the diagonal passing options, such as the one of the no. 8s or a winger moving inside, ahead of the ball or apply pressure to the false full-back.

When Delph is higher up the pitch, he is valued in possession for City. The 28-year-old uses his body, particularly his back, excellently when protecting the ball, getting out of tight situations using quick shifts of weight and direction changes. This explains how he is resistant to pressure and able to play in tight spaces. Plus, Delph’s value in possession is expanded thanks to his ability to hit the high diagonal balls mentioned as part of City’s forward progression earlier, alongside his understanding with Silva and Sané about positional rotations, ensuring that one of them remains central at all times during the flow of the match.

However, it is not exclusively Delph who plays the false full-back role. Danilo has slotted into that role at various points throughout the season, most notably against Swansea City in December. Guardiola interprets the role differently for the Brazilian, and he ends up having different responsibilities as a result. For Danilo, he will be more defensively-minded than Delph, allowing Fernandinho to move up to attack more and occupy positions closer to Silva and De Bruyne in the process. In addition, his use as a false full-back is different than Delph’s in that he will mainly be positioned in the centre to circulate the ball, rather than breaking the lines. Most of his use is for protecting the ball in possession, not making the same kind of penetrative passes that Delph completes.

Danilo here moves inside as a false full-back to assist with maintaining possession and switching the play, rather than moving in between the lines of the opponent.

Walker sparingly occupies positions that the false full-back role would occupy, but these are predominately temporary as a result of positional rotations with Sterling and/or De Bruyne. Walker’s attacking habits as a false full-back differ in one respect to Danilo. Walker will look to attack more through underlapping runs in the right half-space, starting his runs from interior positions during such rotations. When in possession during build-up, he will generally look to protect the ball when receiving it in the middle and rotate back out wide after his pass to restore the original team shape.

The resurgence of Delph, in particular, shows the ingenuity of Guardiola to come up with solutions to problems plaguing his team at a given moment in time. With Mendy out for an extended period in September, it appeared that Manchester City would either have to delve into the transfer market for another left-back, or play somebody out of position. Delph deployed at left-back opened many eyes at first, but Guardiola found a way to blend Delph’s prior skillset with the needs of his team in attack.

Conclusion

When Guardiola arrived in England in the summer of 2016, the usual and, quite frankly, unjustified doubts whether he could reproduce the success he had on mainland Europe were spread. There are still those who believe the Premier League is a unique fortress one cannot conquer as easily as La Liga, Serie A or Bundesliga. Guardiola, however, has remained unfazed by doubters and habitual nay-sayers who may accuse the admirers of the Catalan coach of being short-sighted tactic hipsters. In fact, anyone who questions the general quality of Guardiola is short of any substantial argument, unless they want to criticise him for investing a lot of money in a league where even those who battle relegation spend heavily.

While analysing the City team and how they work under the guidance of Guardiola, it became crystal clear how the 46-year-old adjusted to the players available and the tactical habits the team had before he arrived. He did not just turn everything upside down and create a new City side in a vacuum. Instead, Guardiola came up with a different concept than he had used at Barcelona and Bayern, without betraying his footballing principles.

Outside of Guardiola’s accomplishments, several City players have shown how they are world-class in regards to their technical and tactical abilities. De Bruyne and Silva may be those who shine the most, but who would have thought that Delph, Walker or Sané could fill out the roles Guardiola gave them. Just like he transformed David Alaba and Rafinha into versatile defenders who now can easily play in the middle of the back line, he has managed to use their skills and repackage them. It would not be possible without coach Guardiola as it would not be possible without the right players willing to learn and evolve. No one ever questioned they did not have the talent. But talent alone does not make you superior in today’s football.

9 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

kobach April 5, 2018 um 8:22 am

What do you think about the match vs. Liverpool?

minde March 18, 2018 um 8:30 pm

Hi,

It seems that the main difference between last year struggling Guardiola and this year is that players like De Bruyne, Silva, Fernandinho become a monsters in a physical sense. They never get tired. All Guardiola teams had this unnatural physical superiority against their rivals. Why none of the analytics mention this simple yet very important fact talking about Guardiola tactics. Without press and his players physical ability to get first to every ball his tactics would be not so successful for sure..

tobit March 19, 2018 um 1:16 pm

It’s not only the players who have improved. A big (to me it’s the biggest) part of Citys success lies in their strong and versatile structure. Wherever the ball goes a City player can reach it with far less effort than last season (or than other teams could). De Bruyne is far less physically monstrous than for example Sissokho of Tottenham but he is superior in pretty much every other aspect of the game – his vision allows him to see things earlier (and therefore react faster), due to Citys superior structure he has to cover less space and his technique allows him to control more difficult situations.

With Klopps pressing-schemes it’s quite similar. They “simply” rely less on (individual) physicality because their structure allows them to. Preparing these structures takes time on the field (establish a proper counterpressing structure while you’re on the ball, not when you lose it) as well as on the training grounds (set principles for every player when to press ans when to fall back, find a fitting shape, …). Many other Premier League teams don’t put much emphasis into that, instead they try to improve their physicality to match their opponents on an individual level or just try to not get injured.

Patric January 20, 2018 um 12:51 am

Brilliant. Thank you!

Ancelotti’s eyebrow January 13, 2018 um 11:32 pm

Would be interesting to watch this team play against Zidane’s untactical Real Madrid.

LdB January 5, 2018 um 1:01 pm

Awesome article, thanks for the work!

Nick January 4, 2018 um 9:36 pm

This is absolutely fantastic – opposition scouts will use this as sacred text!

Sebastian January 3, 2018 um 3:36 pm

Is the article also in German available?

CE January 3, 2018 um 7:21 pm

Hi Sebastian, I’m afraid we won’t be able to provide a translated version.