City triumph in tight south-coast encounter

For much of the early stages of this season I have been unable to write for various reasons. During that time there were a number of interesting games and impressive performances. In this series I will analyse aspects of some of these matches.

Bournemouth’s early pressure

In the opening exchanges of the game, the home side were keen to keep the game in City’s half and create a frantic opening period. Bournemouth were able to achieve this due to a number of reasons;

Direct play and 2nd balls

When Bournemouth won free kicks, goal-kicks or possession in open play they often played long towards City’s defence. King and Defoe were tasked with creating duels for these long balls. Although they weren’t expected to hold the ball up, the duels would reduce the City defenders’ ability to make accurate nodded passes. Gosling, Surman and Arter were key in staying close to the game, and anticipating where the ball would land to either win the second ball, or create immediate pressure on the receiver.

High pressing

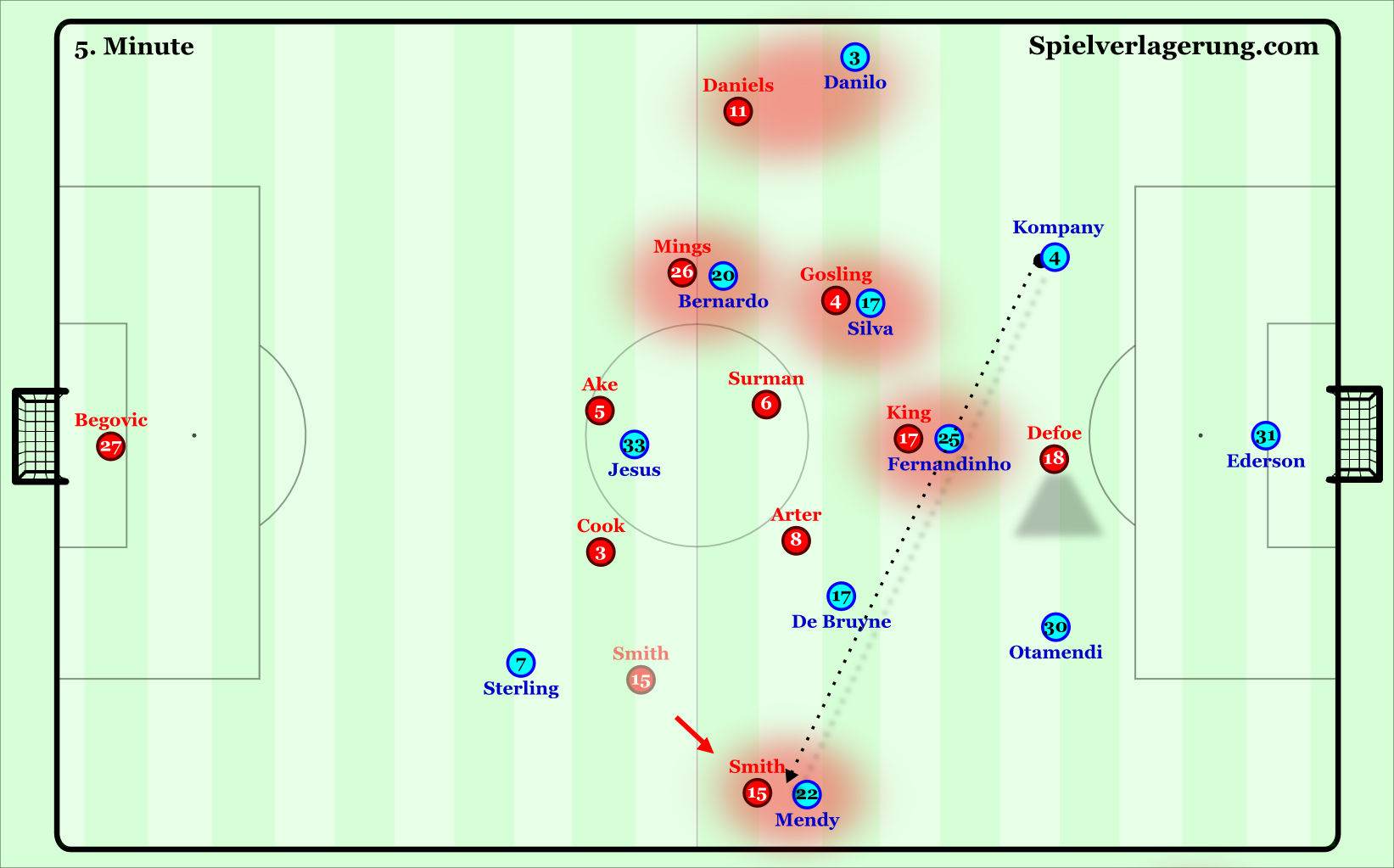

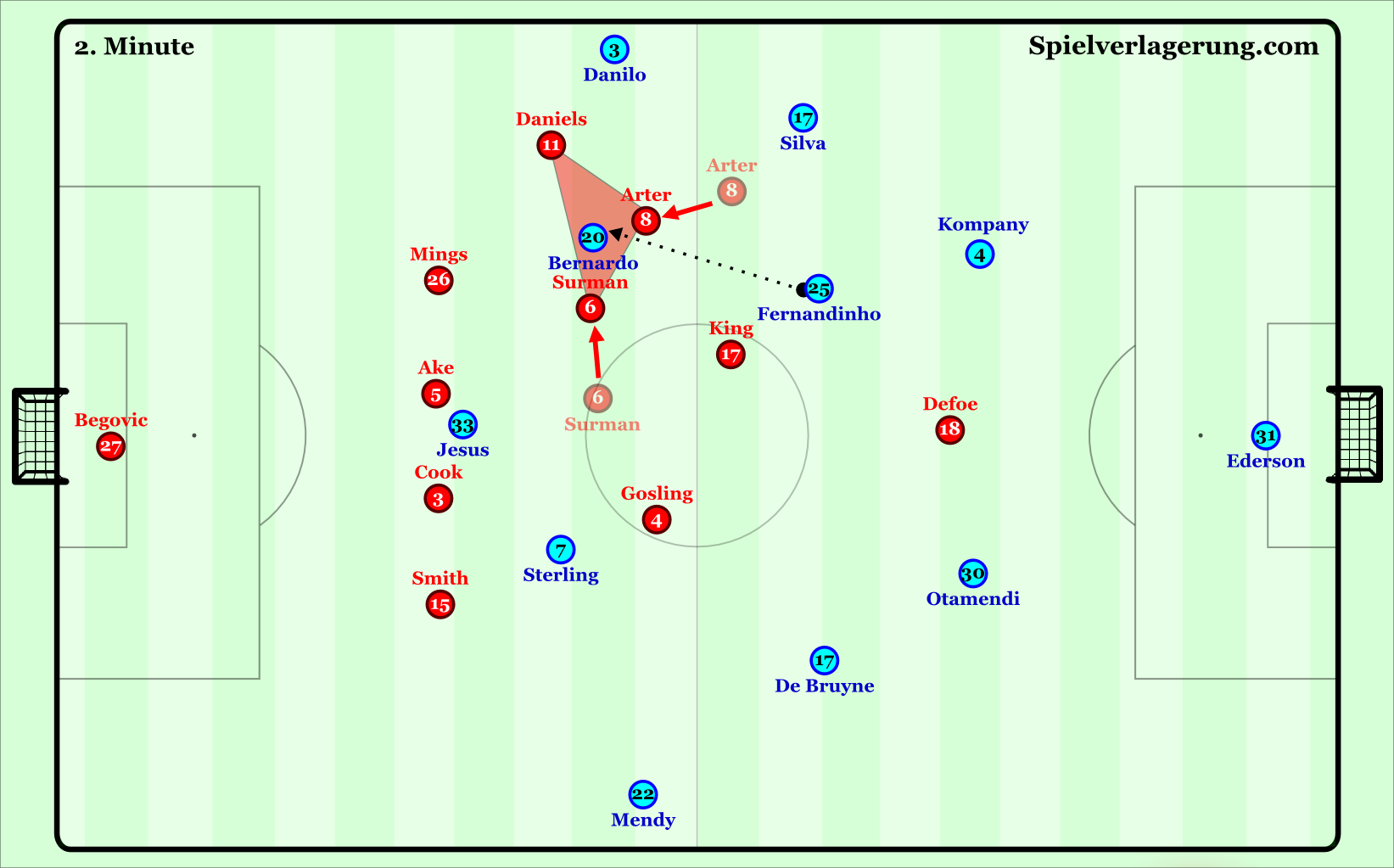

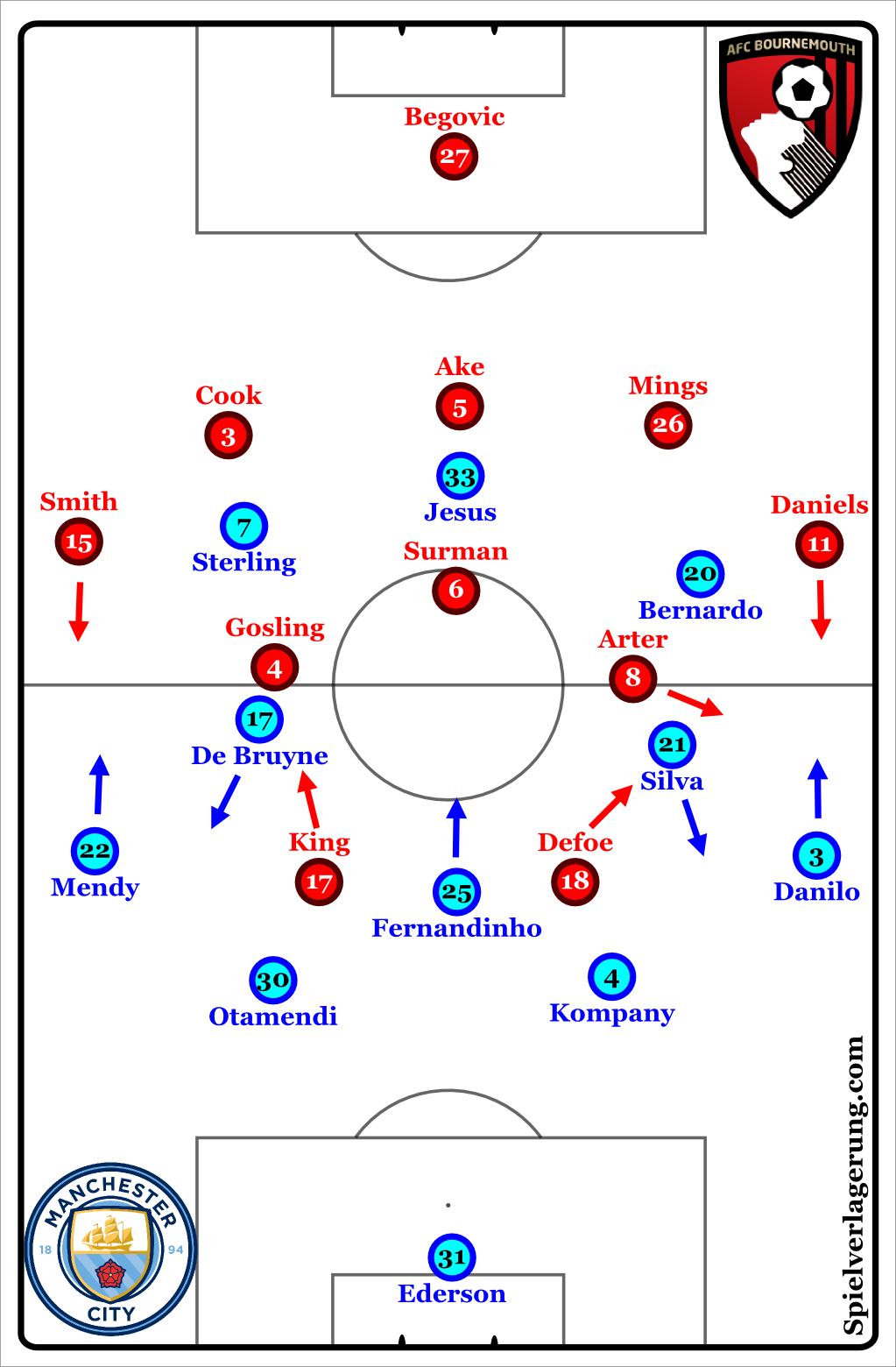

From the base 5-3-2 shape, Howe’s men pressed aggressively with high levels of freedom to leave the lines of defence and create pressure. King often dropped deeper, making a 5-3-1-1, from here Defoe was focused on pressing City’s centre backs whilst blocking passes across between them, this was a vital job. Due to the narrowness of Bournemouth’s first two lines, switches would break their access allowing City to push them deeper.

Behind Defoe, King was focused on blocking Guardiola’s men from using Fernandinho in build-up. At times King’s pressing position between City’s midfield and defence meant he had brief separation from City defenders when Bournemouth regained the ball, he was thus a good target for the first pass to start counter attacks.

The wide midfielders in the line of 3, Arter and Gosling moved out of position early to press City’s build-up when the ball was on their side, whilst Surman constantly moved across to cover spaces behind them. Daniels and Smith (the wing-backs) also had the licence to move out of position quickly, and importantly created access as soon as a City full-back received a long pass, preventing them from moving forwards.

Bournemouth’s pressing was based on blocking City’s short passing options and having access to the ball carrier, this would force City to play longer passes out of pressured areas. Forcing these longer passes gave the defenders furthest away from the ball time to step out and create pressure around the area the ball would arrive in.

Blocking City’s short options existed in both a vertical and horizontal dimension. Due to City’s spacing in the first two lines, Bournemouth’s attempts to create pressure would mean opening space in spaces within their defensive shape. This was particularly evident in the half spaces behind Gosling and Arter who moved high to press De Bruyne/Silva.

Backwards pressing & wide triangles

Whilst the aggressive pressing positions of the Bournemouth players opened spaces behind them, they were able to cope well with this due to strong backwards pressing. From his position blocking switches between Otamendi and Kompany, Defoe would work across and could press from the blind side if the near City centre back received a back pass. This was in line with the general strategy of blocking City’s options of playing short, and forcing them into hasty attacks under cumulative pressure.

The advanced positioning of Arter and Gosling at times opened space behind them for Bernardo/Sterling to receive. Again, Bournemouth’s backwards pressing allowed them to cope with this and regain possession from potentially dangerous situations. Although Bernardo/Sterling appeared to have space, these passes would be met with backwards pressing from the nearby central midfielder, Surman working across from the centre, and the near wing-back moving forwards. As such they created wide triangles, creating pressure and taking advantage of City’s weak supporting structures due to the hasty progression.

This ability to force City into longer passes and risky progressions were behind the transitional nature of the opening exchanges, and when Daniels opened the scoring it was a fitting reward for Howe’s men’s strong start to the game.

GK press

When City tried to build-up from Ederson, either from goal-kicks or in open play; Arter would move into Bournemouth’s front line, creating a 5-2-3 structure. This allowed Bournemouth access to both centre backs and Fernandinho. The 5-2-3 allowed the home side natural access to City’s build-up, with each player having a clear opponent within their region, man-orientations were thus used to block short passes on the near side. When Ederson received back passes he was pressed by the nearest player in the front 3, whilst using their cover shadow to block the pass into the opponent they were marking. As such, Ederson was forced longer.

City settle into rhythm as Arter drops

Around the 20th minute, Arter stopped joining the first line, presumably an intentional decision to sit deeper particularly since Howe’s side were in the lead. However, initially the strikers still pressed aggressively, with the use of Ederson, the centre backs and Fernandinho they were surrounded by a build-up diamond. With this 4v2 underload they were realistically unable to challenge City’s build-up, and in fact opened large space in front of the midfielders for City to progress through.

With the reduced aggression in Bournemouth’s general pressing positions, City were able to establish their possession rhythm. Within their possession phases there were a number of interesting aspects;

De Bruyne, Silva and half space switches

Positioning

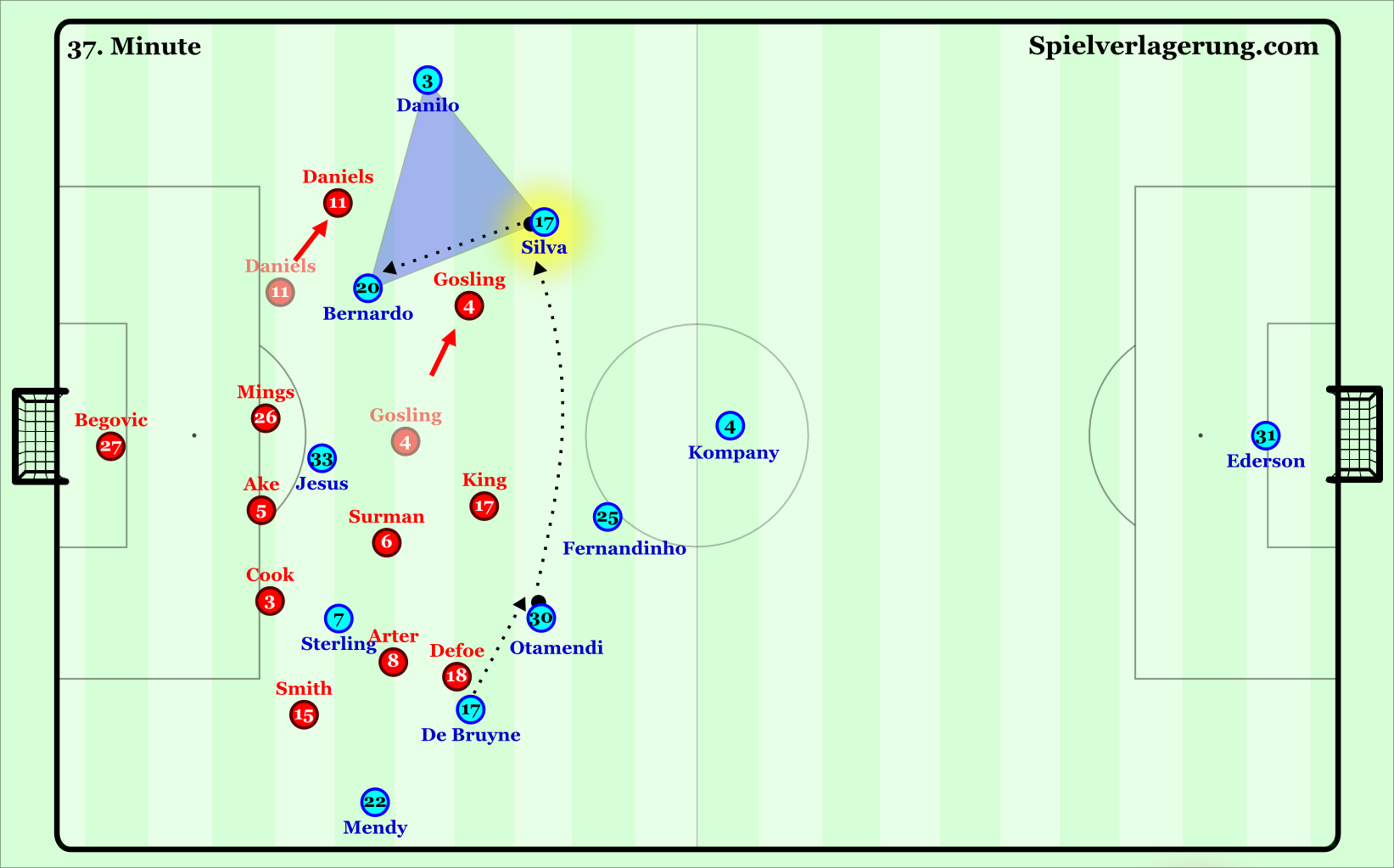

With the full-backs playing high and wide, and the wingers playing narrow, City’s midfield maestros were positioned deep in either half space, acting as the base of the wide triangles. In this position they were in space besides King and Defoe, as well as being positioned in front and wider than Gosling and Arter. As such, they could often receive the ball in space with opponents having to move out of position to press them. Fernandinho’s position between King and Defoe was vital in creating space for the playmaking midfielders.

Alternately, if Gosling or Arter moved out of position to block the pass into De Bruyne or Silva, they would open the passing lane into Sterling/Bernardo in the advanced half spaces. These players could then lay the ball off into De Bruyne/Silva who would receive the ball facing forwards, and with runners to feed.

The positioning of the creative midfield pair also led to constant half space switching to relieve pressure and gain territory. When the ball was on one side, Bournemouth’s furthest midfielder had to shift across to keep small distances to Surman who had large covering responsibilities. As such, the far City 8 was often in large space, these half space switches created the possibility to attack through the half space or wing with temporary 3v2 situations.

Diagonal orientation

Interestingly, the right footed De Bruyne played in the left half space, whilst the left footed Silva played on the right, this created a diagonal orientation in the actions of the midfield pair. With the time and space their positioning often allowed them, Silva and De Bruyne often dribbled/passed diagonally due to the preference to use their stronger feet.

With this diagonal orientation, they were able to keep several options open, such as the vertical pass into the winger ahead of them, the diagonal into Jesus, diagonal into Bernardo and crucially the half space switch to the ball-far 8. This led to hugely dominant spells of circulation where City could relieve pressure with switches to the far half space.

Freedom

The only part of the field that wasn’t immediately accessible for De Bruyne and Silva was often the near wing (mostly in

Bournemouth’s 2nd half 5-4-1 where the wide midfielders cut City’s access to the wing after switches). In situations like these, the ball-far 8 often overlapped, due to the direction of their movement they could receive the ball with a field of view facing the open wing.

This freedom to move from their half space position was also used to create overloads and breakthroughs on the ball side when Bournemouth’s defence were able to defend stably against the 8, full-back and winger triangle.

Offside positions and combinations

On several occasions in the game, the Citizens’ forwards could be seen remaining in offside positions whilst their team-mates began attacks from deep, this was an interesting tool. By staying offside, they were out of the immediate perception (as per the blind side) of their opponents, and with late dropping movements into the space behind Bournemouth’s midfield they could present themselves as an option to advance.

Ake, Cook and Mings often pressed forwards to close the space behind the midfield when a City forward received the ball in front of them, and they had the licence to do so due to the extra cover of a 5 man back line. However, the offside positioning of Jesus, Sterling and at times Bernardo meant they were unaware of when exactly the City forward would offer themselves to receive the ball. This led to a number of successful progressions with lay-offs, adding quick breakthroughs to the stable possession that Guardiola’s side enjoyed.

Bournemouth’s build-up struggles

Later in the first half the home side experienced issues in trying to build attacks from their defence. They were consistently unable to play into midfield, and were forced to pass along their back line and into the wing-backs. Analysing the cause of this brings up interesting points about structural interaction.

The Cherries tried to build from a base 3-1-4-2 shape, with Surman as the deepest midfielder in the centre. The match-up that this created against City’s narrow 4-3-3 pressing structure was hugely problematic. When Ake had the ball, Jesus could press him vertically blocking the lane to Surman in the process, the distances between Gosling to De Bruyne and Arter to Silva were constantly very small, making Bournemouth avoid these passes. As such, the ball had to be passed to the next defender, and the near winger in City’s front 3 would step out to press diagonally, again blocking the pass into Surman.

This left the ball Cook or Mings under pressure, and with only the pass to the near wing-back available. This pass was also met with pressure as City’s near full-backs stepped forward early. As such, the wing-back would often receive the ball on the wing, facing backwards and under cumulative pressure. It was no surprise that this often led to losses of possession.

Far from merely talking about numerical match-ups, this was a clear problem of the interaction between Bournemouth’s structure and the opponents’ creating unfavourable situations. The 1-1 in the centre (Ake and Surman) made Jesus’ job of pressing Ake and blocking Surman very simple. The large width covered in the back 3 meant that Howe’s side lacked a short sideways option in the first line to move the ball away from Jesus’ cover shadow and open the lane into the holding midfielder.

A potential solution

A 2-3 structure in the first two lines would create the aforementioned short option to open the lane into Surman. However, another solution requiring a smaller structural shift was possible. Namely; a 3-2 structure.

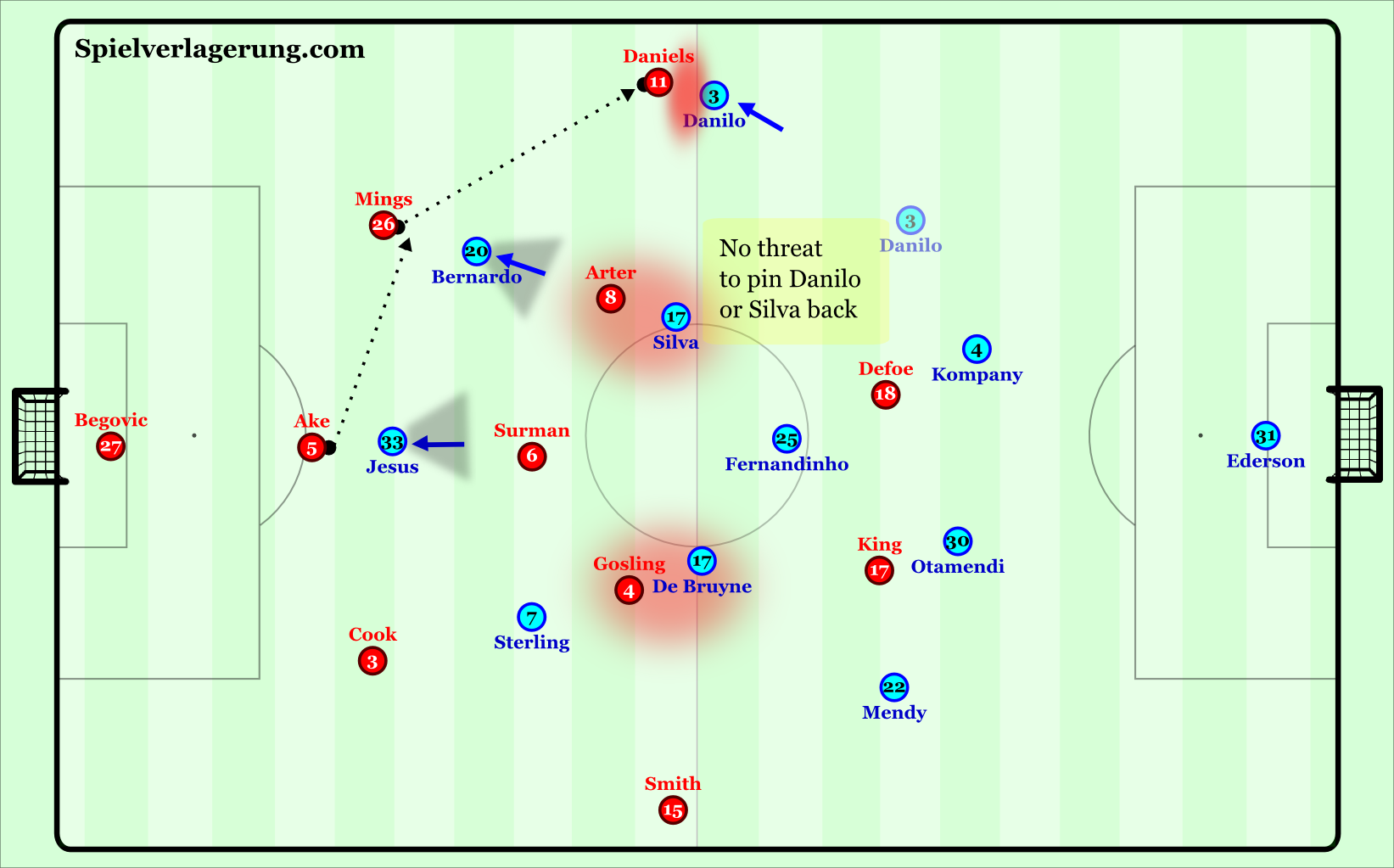

With two players at the base of midfield, Ake would have had two options behind Jesus, with both able to split and stay out of his cover shadow. Interestingly, there were one or two occasions where Gosling or Arter played deeper alongside Surman creating a 3-2 build-up structure. However, this was still not effective in creating a more advantageous interaction because they lacked a threat behind Silva/De Bruyne. Without the threat of players behind them, the ball-near City 8 could simply follow their man higher, preventing Gosling/Arter’s participation in the build-up.

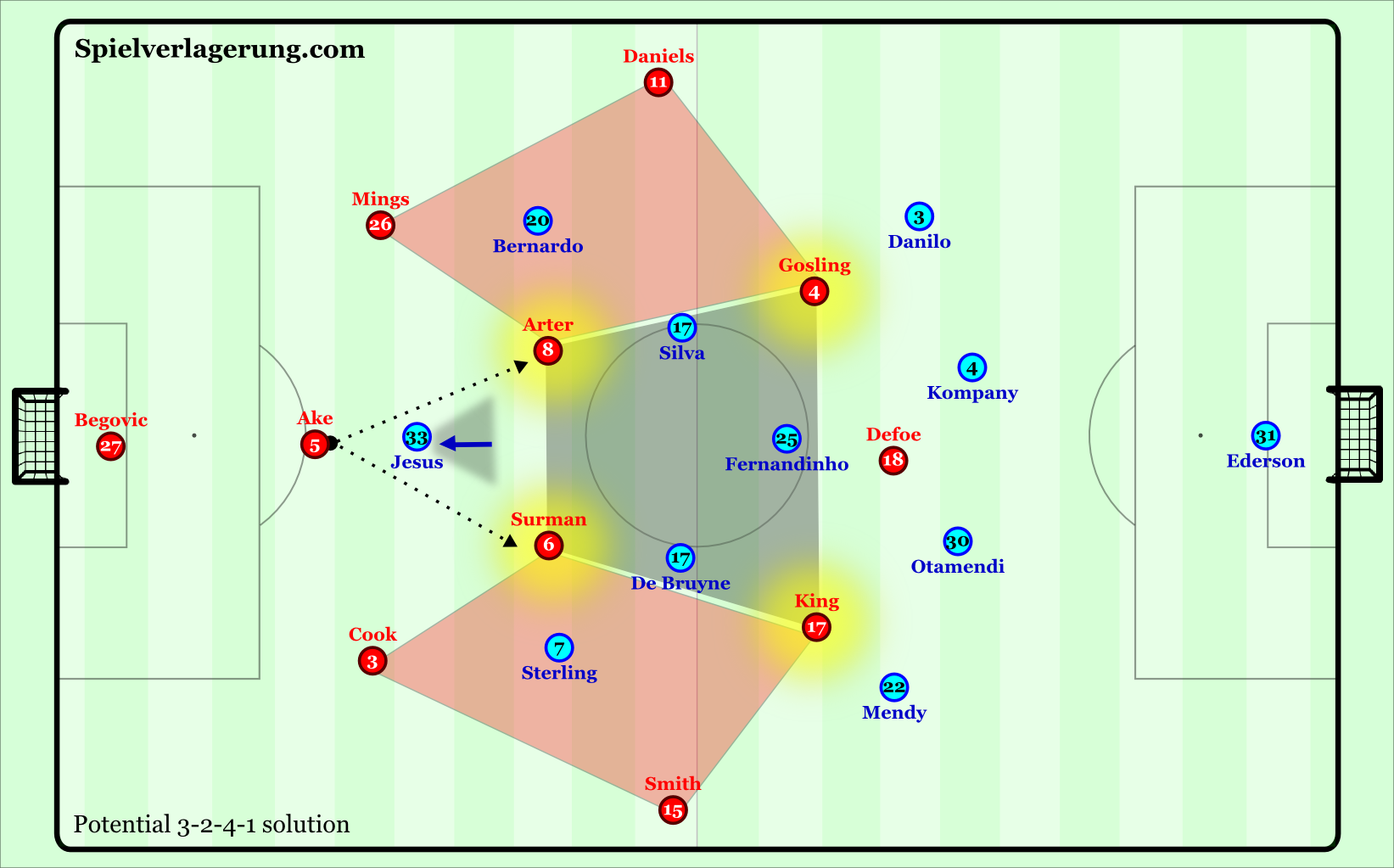

A 3-2-4-1 could be a functional adaptation to create a better build-up. In addition to two options to play beyond Jesus in the centre, there would be players in either half space behind Silva and De Bruyne. This would pin City’s 8s back, creating more space for the two deep midfielders. Alternately, they could play directly into the half space if Silva/De Bruyne moved out of position early. Cook and Mings would be at the base of a diamond structure, creating diagonal options to play inside outside, as well as a vertical option, depending on the pressing direction of Sterling/Bernardo.

The threat of runs in behind from King and Gosling could also prevent Mendy and Danilo from pressing high on the flanks, giving more space for Daniels and Smith to receive the ball.

Howe moves to 5-4-1 & City’s structural response

In the last few minutes of the first half there were a couple of instances of Defoe dropping into a left midfield position, creating a 5-4-1 defensive shape. This was done inconsistently until half time when they switched to constantly defend in a 5-4-1. This was a reaction to the issues City’s half space switching was causing. With a wider midfield line, Bournemouth would theoretically be able to create access after half space switches and thus not be pushed backwards as easily, as well as forcing City wider earlier in build-up.

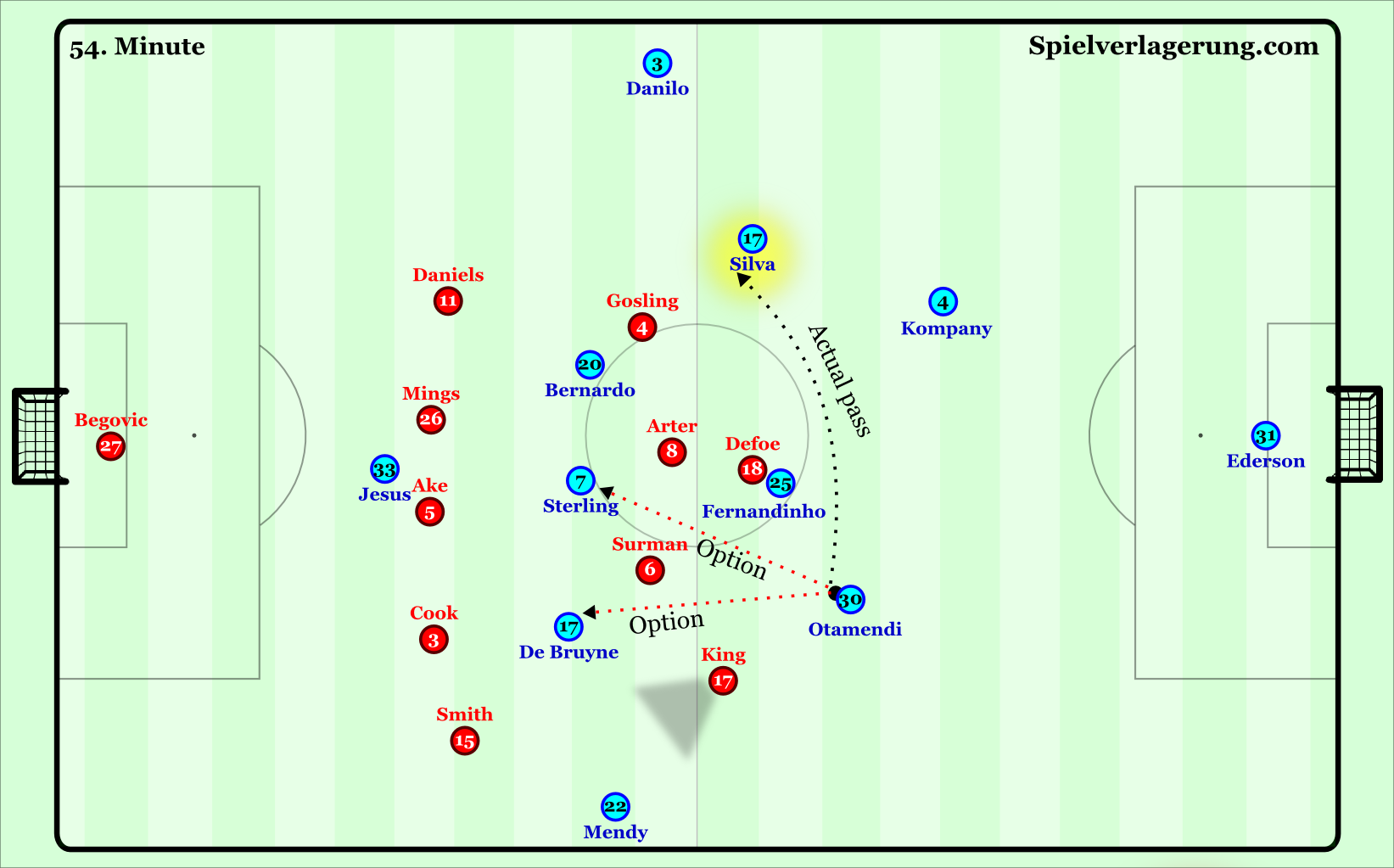

In response to Bournemouth’s 5-4-1, Silva and De Bruyne were positioned higher, and more narrow behind the home team’s midfield line, this was a logical response. In the 5-4-1, the lack of presence in the first line meant Bournemouth could no longer disturb City from building through Fernandinho and the centre backs. As such, City’s 8s were no longer required in deeper spaces to stabilise the build-up, and could now add to the offensive presence needed to break Bournemouth’s 5-4 block.

The more advanced roles of City’s interiors led to Mendy and Danilo playing deeper on the flanks, creating bigger separation between them and Bournemouth’s wing-backs. By positioning the 8s inside and behind the Cherries’ wide midfielders (Gosling and King), they could either receive directly from the defenders, or open space for the pass to the full-backs if Gosling/King stayed narrow to block them.

The distance between City’s full-backs and Bournemouth’s wing-backs meant Smith/Daniels had to make longer runs for access. Theoretically this could have created space for City to break through the wing behind the pressing wing-backs. However the movements to exploit this were used all too rarely.

For Howe’s men, the change allowed them to force City to use the wings earlier in their build-up, with the wider midfield line they were better able to control the half spaces. This made City’s possession game less threatening than it was towards the end of the first half. However, probably by conscious decision, the deeper defending and lower presence in offensive areas meant the home side lacked a threat on the counter attack. With Defoe often facing duels against Kompany, Otamendi and Fernandinho to receive possession, it was little surprise that Bournemouth struggled to move up the pitch for long periods in the second half.

Conclusion

This was a highly interesting encounter which was eventually decided with a last-gasp winner from Raheem Sterling. Although it meant beginning the season with 3 straight losses, there were a number of positives to take away from the performance for Howe’s men, not least the efficacy of their early pressing.

Guardiola’s side displayed several interesting structural adaptations from last season in the 4-3-3 shape. A lot of the plays were spoiled by weak technical execution, and at times weak individual decision making, however there were hugely impressive signs which have since manifested in consistently large victories.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen