Canada’s soccer: A work in (need of) progress

Is a country that is struggling to stay in the top 100 of the FIFA ranking worth writing about? Does anybody even care about “soccer”, when there’s baseball, ice-hockey and other games, that use the name “football” for themselves?

It was important to me, that a Canadian voice is involved in writing this article to not be suspected of an ‘arrogant European view’ as there are several critical and progressive views everywhere in the country. I am happy to have collaborated with Yiannis Tsalatsidis throughout this article, YT has experience ranging from grassroots – club – college – high performance coaching and is one of the most promising young coaches in the country.

In his Keynote ‘The Development of Soccer in Canada’ Jason de Vos did not shy away from talking about the ugly truths within the Canadian system. This is expected from someone who holds the title of “Director of Development” for the country. One thing is clear, he does not fit the cliché of a know it all ex pro who claims to have all the answers based on past experiences.

Born in London, Ontario, he managed to have a respectable career and collected an impressive 170 appearances in the English second tier, fittingly called the ‘Championship’ and also lead Canada in bringing home a Gold Cup in 2000.

Canada is ranked 10th in the world for registered players and that jumps to 7th when you only count youth players. Yet the country still struggles to crack the top 100 in the FIFA rankings. Regardless of the fact that most of these registrants play soccer for solely recreational reasons (most are looking for a second sport to play next to hockey) one thing is clear: Canada does not lack a player pool.

Even with the consideration of Canada’s multi-sport culture (which should enhance player development) we still find a lack of player progression from this large pool. Instead, the organization of soccer in this context seems to be the major issue. The link between rather abstract problems from a macro level and the thousands of everyday playing/training experiences can be summed up in one word: Coaching.

In the next few paragraphs I will provide analysis from both a strategic and tactical point of view. Firstly, I will discuss general ideas and the ‘tactical culture’ in Canada (or the lack thereof). Afterwards, I will explore the recent performance of Canada’s men’s national team in the friendly versus Jamaica which will be supported with video material.

From this, I will move on to discuss the professional spectrum of Canadian soccer and the tactical level of the respective teams in various leagues in North America linking it to the previous findings. This includes samples from rather randomly selected games. Reoccurring topics are again put into separate videos and graphics. I did something similar in my first ever article for Spielverlagerung.de, when I offered a critical view on German youth soccer.

At the end, I will share some personal insight to my (daily) working process in a local club. This will ultimately lead us back to the heart of it all: Coaching soccer.

Canada’s tactical culture or the lack thereof

‘We always need to talk and think football (soccer)’ – That was the message on repeat from world renowned soccer mind Marcel Lucassen to his players during a week-long camp in London, Ontario. What sounds like the most obvious thing to do, is often neglected in the world of coaching.

The main strategies seem to be shouting at the referees, which is often the case especially once a game reaches its tipping points. Or motivating the players through phrases like: ‘Let’s focus, guys!’, ‘Be strong!’ ‘Keep pushing’ et cetera. Some coaches also see a viable solution in shouting insults at their players without giving any transferable solutions of how to improve within the actual game context.

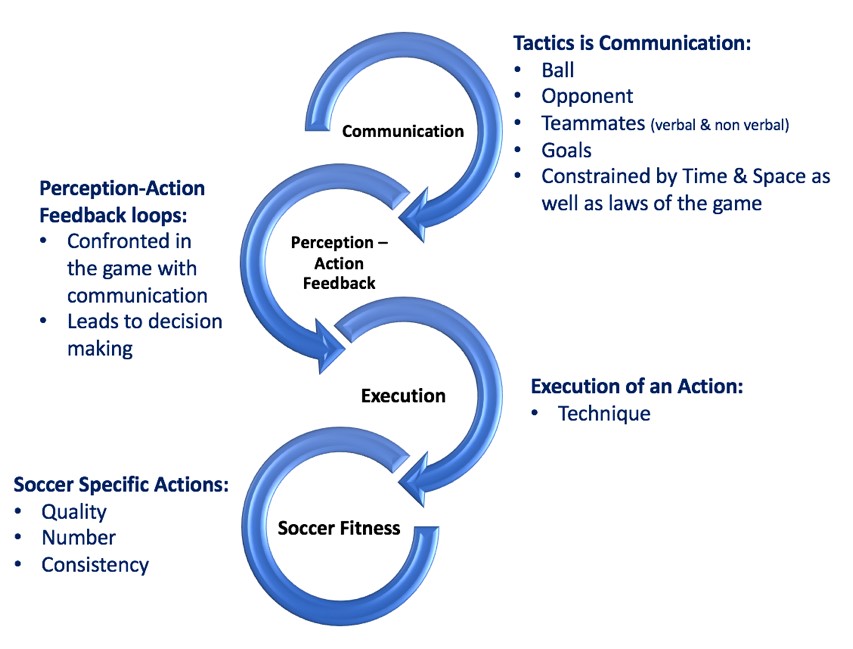

Communication is at the highest order in the soccer theory used by Raymond Verheijen. This doesn’t necessarily mean verbal communication but more importantly communicating in a non-verbal way. This non-verbal communication is at the heart of ‘tactics’ and what tactics really are. It is what distinguishes play between the different phases of the game.

For the individual, on the level of ‘game insight’, is all about performing soccer actions, that are as good as possible. The decision-making and execution can and should then be evaluated based on temporal-spatial components such as position, moment, direction and speed of the soccer actions, which makes it specific to any situation happening on the field. This is directly related to what people generally might call ‘technique’.

Eventually, it’s not only about performing better actions, but also more actions per minute for as long as possible and ensuring they are as good as possible. This is the true essence of soccer fitness. It is not to be separated from (verbal & non-verbal) communication and game insight, but inextricably linked to both of them on a lower order. If I don’t know where, when, and at what speed to run, my running is simply useless in a soccer context.

In Canada, the general perception of what’s needed from a fitness level is extremely decontextualized from the game of soccer. A common compliment is that he or she is a ‘great athlete’, and not that they are a ‘great player’ (emphasizing the most important part of soccer: playing, which is indirectly linked to game insight). This boosts the promotion of players born at the beginning of the selection period due to their physical dominance compared to other players, who can be born up to 12 months later – ‘relative age effect’.

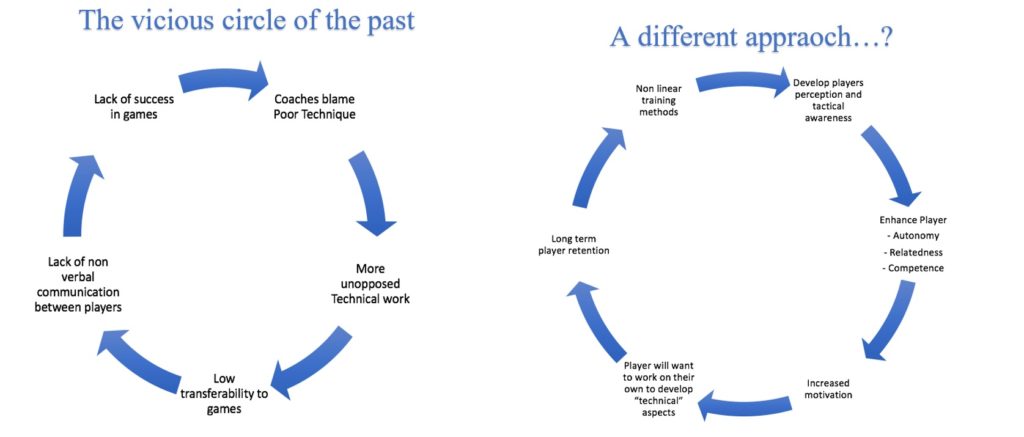

In Canada, there is still too much time wasted with the obsession of perfecting techniques in isolation as well as focusing on instructional coaching methods that don’t justly prepare the players to deal with the true complexities of the game.

More times than not the training is so far removed from what the game actually looks and feels like that the players struggle to achieve what the coach incorrectly deems to be success in their quest for ‘technical perfection’.

The result? Players unable to create or exploit key spaces, unaware of cues and triggers in the game that give clues on how to act or unfamiliar with transition moments. Surely this method is not conducive of long term player development, which leaves us with a decisive question: Are the players we are progressing to higher levels of play doing so by strategic design or predominantly by chance?

“The highest technique is to have no technique. My technique is a result of your technique; my movement is a result of your movement. I have no technique; I make my opponent’s technique my technique. I have no design; I make opportunity my design. One should not respond to circumstances with artificial and wooden prearrangement” – Bruce Lee

Adding to that, the way of watching soccer is different in Canada than it would be in Western Europe where the culture offers much more experience to watching full games and directly or indirectly observing concrete football actions – be it only in the context of a social gathering.

This doesn’t imply, that the quality of observations is automatically at a higher level. The mere confrontation with the game from a young age itself is of high importance.

Canadian children interested in soccer are starting to get more exposure to this information as it is more accessible than ever. An increasing number of players younger than 10 years old talk about and replay moments of big games like the Champions League final where they use their imagination to replay the moves of their idols Cristiano Ronaldo or Gianluigi Buffon.

What would they see if they will watch their own national team play? Who is there to draw inspiration from? What does it look and feel like to play for the Red Maple Leaf?

Canada’s national team

Since March 2017, the Ecuadorian Octavio Zambrano has taken over the reins of the men’s national team, which has seen some significant changes in that time period. His predecessor Benito Floro, former coach of Real Madrid, showed the desire of Canada Soccer to move away from a rather British style of play focused on disconnected transitions, long channel balls, and tackling towards a more controlled game.

The grand seigneur didn’t have the expected impact. Octavio Zambrano, on the other hand has already changed the structure of the roster introducing younger players such as 16-year-old Alphonso Davies. Davies went on to win the golden boot and the best young player award at the Gold Cup and earned a spot in the best XI of the tournament in the process as Canada reached the quarter final.

A certain courage is already visible in this and the aim is to reflect this in the playing style as well: ‘Now, within that identity of being a diverse nation, we can’t try to emulate playing like Germany, or like Dutch teams, or like Brazilian teams. We don’t have to do it, and we shouldn’t do it. We have to play like Canadians’.

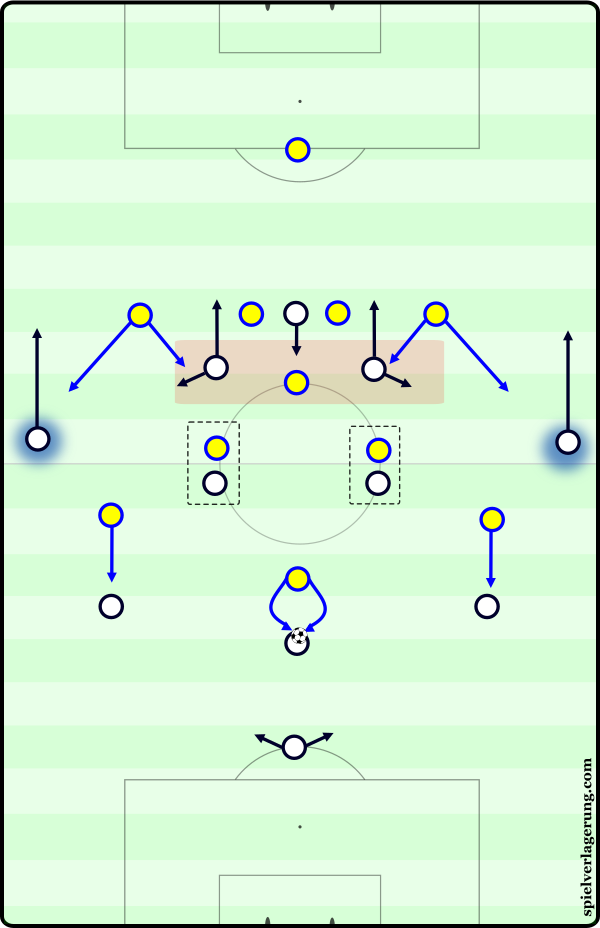

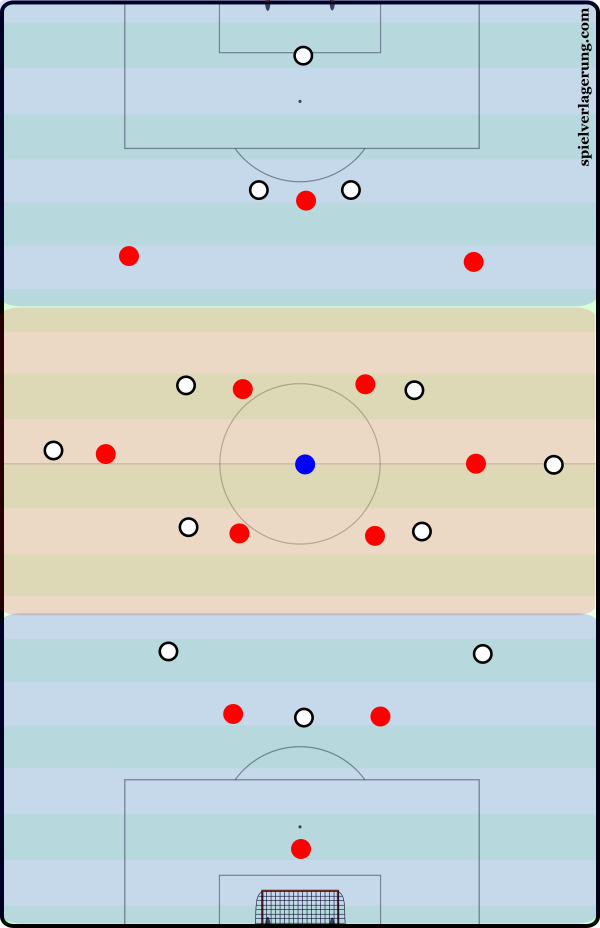

Canada set up in a usual 4-3-3 formation in their first test match after the Gold Cup against Jamaica. On one hand their game is heavily based around different rotational movements by the three central midfielders on the other a significant focus is placed on playing through the wings.

In the best periods of the game that leads to an easy manipulation of the opponent’s man-orientations. Against a zonal orientation and with space between the lines, the wingers tend to play a more prominent role as they come inside to occupy these zones while the full-backs push up. This was especially significant in the second half as Cardiff City player Junior Hoilett almost played a free role in behind Jamaica’s midfield.

When the dynamic movements are done properly and in relation to each other, Canada is capable of beating the first pressing line(s) quite easily. However, problems arise due to their otherwise prevalent focus on stability in possession. The defensive midfielder Piette constantly drops and is oftentimes joined by both central midfielders Osorio and Hutchinson.

At the same time, the full-backs stay rather deep. Even if progression is possible during the buildup, there’s nearly no presence in higher zones or inside the opponent’s block. Strategically speaking, there’s no direct solution for the second next pass. This results in a recycling of the ball of where play (in accordance to the collective line of thought) must start over and over again, which naturally costs time.

The structure is oftentimes only beneficial for keeping the ball without exploiting strategically valuable spaces. Central occupation is neglected and if available, the first look is to turn or face outside, not to the open towards the middle. The necessary play from side to side is either only possible through back passes or through direct switches into relatively isolated situations.

At the same time, the dropping players don’t find themselves in favourable situations as their body position is generally closed. They are facing their own goal instead of being able to face forwards and find more advanced players. Even if the opponent lets them turn, the defense has time to adjust their positioning and their forward options won’t be as accessible.

The orientation on the field is also an issue. Often times the movement off the ball results in blocking passing lines or not respecting the space of teammates in a better position. In a positional style of game the players need a better understanding of how to stay in their zone and when to change positions or not.

At the same time, there’s no collective and coordinated understanding where possible movements create spaces for others. For example, if everybody shows for the ball and is followed, there’s logically either space in front of the opponent’s defense or behind it. To which movement do I play and to which not?

Outside runs for examples have the main purpose of dragging away opponents and create space somewhere else. If you see outside runners mainly as pass receivers, you will again oftentimes come in situations, where they face the touch line and can’t effectively progress.

These are not overly sophisticated concepts, this is of course if they are taught throughout the developmental process. Everybody somehow knows, how to count to three and should be capable to see, where a numerical superiority is. But of course, this needs to be experienced in game situations and constantly mentored by knowledgeable coaches.

Not playing with a clear idea of these general concepts, leads to a highly volatile kind of game. Decisions appear to be random and lacking an intention. In similar situations players might act completely different due to lack of understanding or awareness.

Another example, that is also crucial for the playing style of teams like Barcelona: When do I need to dribble and when to pass? If a center back has space in front of him and the full-back is too deep to be in a better position than him while all central options are covered – Why does the center back need to pass? His dribbling will lead to a first progression and will eventually drag one or more opponents out of their position. This space is then free to be occupied by a team mate for a pass.

In the final third, the main focus shifts to occupying the box with as many players as possible as soon as possible. This leads to highly static crossing situations, if the ball isn’t sent in immediately. As the different phases of the game are connected and directly depend on each other, this also creates a big problem in the moment after losing the ball as the space in front of the box is not covered properly and the players don’t possess the habit to immediately win the ball back after they lose it – collectively referred to as counterpressing.

As already shown in moments of the previous videos, Canada sometimes still creates a good structure for counterpressing, but doesn’t use it properly. Runs are either completely halted, slowed down, or turned around to go backwards (an imbedded defending habit in the Canadian DNA). Or the direction of applying pressure is not correct as the opponent is not guided toward favourable zones where there are supporting players or the sideline, but instead they are allowed to turn towards the middle.

This is another basic strategical concept, which is even more intuitive to most players, but needs to be taught systematically. Let’s look at the game of our 7-year-olds which consists of constant transition and counterpressing. Inexperienced coaches do not like the idea of not having control and instead confuse and attempt to bring order to the game through rigid positioning at the youngest ages ‘Stay in your position’, ‘You’re a defender today’. But once they reach a certain age then suddenly everything is expected to change and become fluid?

https://streamable.com/ol65u

Offensive transitions fit a majority of Canada’s players better as they are generally more used to play in this phase of the game with larger spaces that can be exploited through fast attacks. Still, the movements closer to the goal aren’t always well communicated as players tend to attack the same spaces at the same time.

The initiation of counter attacks seems to be even more problematic at times in the first stage of counters. When there’s a huge space for a counter-attack, the decision-making to play away from pressure is not always adequate to the situation. Under direct pressure the orientation into depth is not success stable enough to exploit deficits of the opponent’s structure.

https://streamable.com/5nb75

If we take a look at the organized pressing of Canada, there’s the same inconsistency. In the first example, we see Jamaica attacking basically the same space in front of Canada’s box. In the first case, Hoilett stops his pressing and the opponent can attack with more speed. Raheem Edwards doesn’t know, whether to attack the ball or to cover space (and which space?). A dribble through the middle is quite easy.

In the second case, Hoilett faces the player with the ball and attacks him. The opponent again dribbles towards the middle, but is surrounded by three players and forced into a trap this time, where he can only lose the ball. Counter for Canada.

https://streamable.com/oh8bx

In their best pressing moments, the Canadian team can effectively force the opponent towards the touchline and create a numerical superiority in order to attack the ball carrier with two or more players. Most of the time, the team relies on creating favourable individual pressing moments where they can aggressively defend opponents that are facing backwards. From this, local compact situations can be created.

https://streamable.com/1c7gi

Especially in a higher press with situationally higher intensity, there’s a good tendency to occasionally disrupt the opponent’s build-up and to create promising transitional moments. But most of the time only the advanced players push higher and follow movements of their respective opponents.

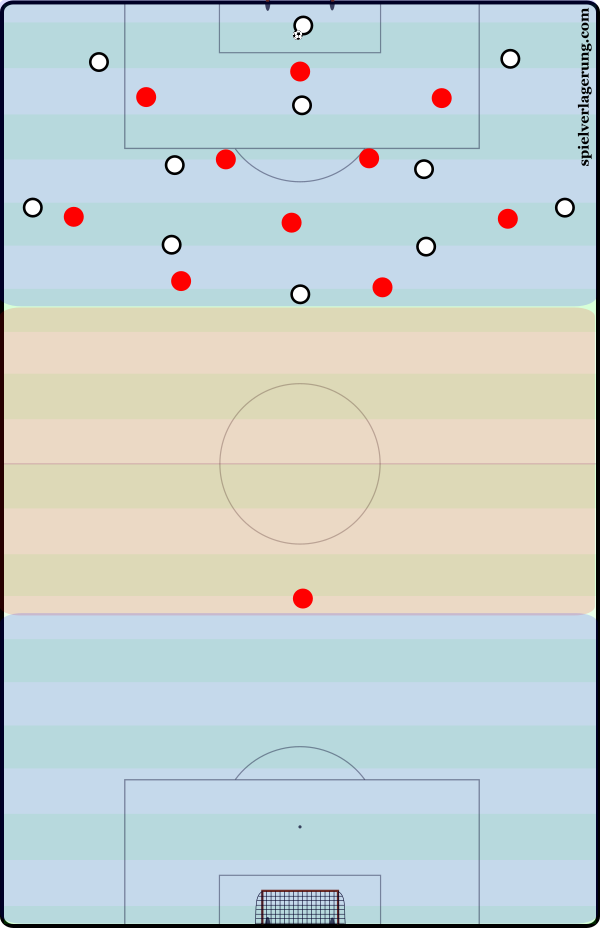

The result: A highly disconnected structure without having collective access to the ball. Especially the space in between midfield and back line which is vulnerable as the latter drops back too early due to being worried more about direct opponents and about disadvantages in speed than about the coherence of the team.

https://streamable.com/7si7i

The overall movement and communication within the back line doesn’t meet general standards. The center backs are used to following their players instead of shifting through to the ball side to increase the compactness and to situationally attack the ball carrier.

At the same time, they don’t react adequately to closed (pushing up) and open (dropping) ball situations and don’t cover the respective zones of their team mates well enough once they step out. At the same time, spaces in front of the back four are exposed and open for rebounds as the midfielders don’t fill gaps consequently enough, especially from the ball far side.

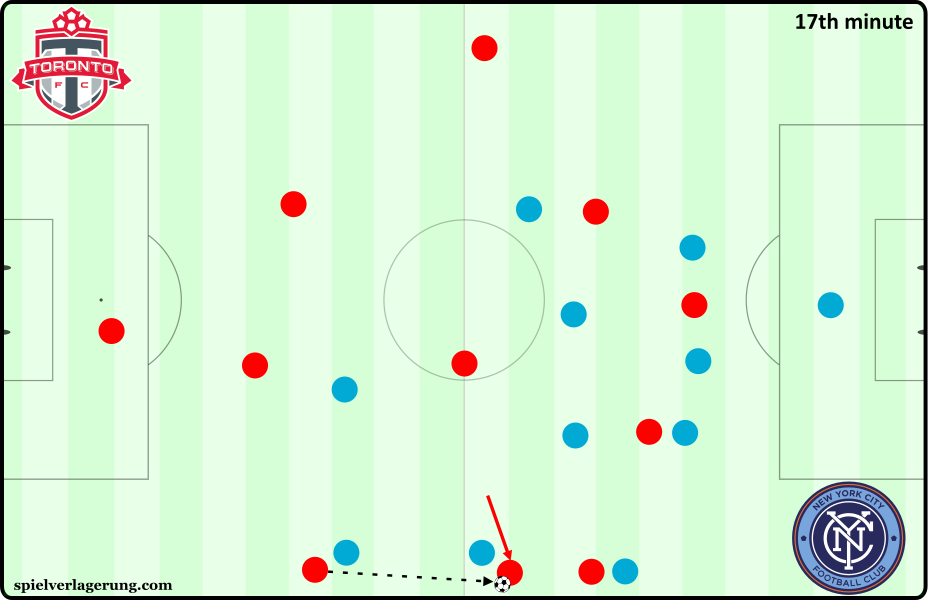

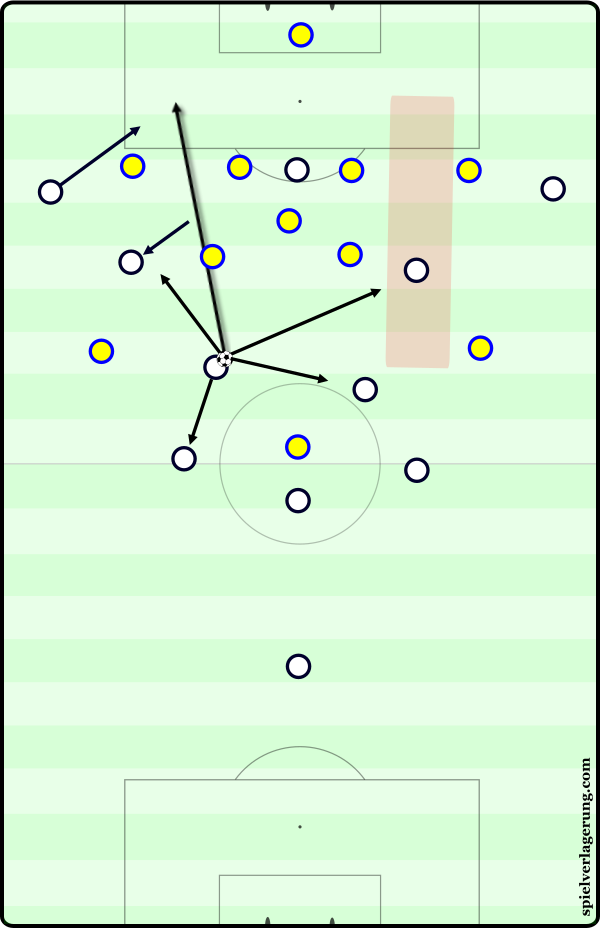

The biggest flaw in the pressing system of Canada is the general tendency to man-mark, which the behavior of the back line only exemplifies. The first orientation is usually to look for a direct opponent and to follow him. A highly reactive approach (as often enough discussed on this blog). You make yourself dependant on the opponent’s structure and constantly open spaces, especially when there’s no continuous pressure on the ball.

Against superior players who can beat you easily in direct duels there will be a general disadvantage. You can only rely on the back four to not allow easy breakthroughs after the progression through midfield will inevitably happen. Against Canada, the easiest way to exploit man-marking is to drag the respective full-back towards the middle and attack the open space. This already proved to be an issue during the Gold Cup.

The box coverage can also turn out to be problematic against fast attacks from the sides. After breakthroughs, when the opponent attacks with speed the deeper players will drop back altogether and might struggle to orient themselves between players and ball. This results in the space in front of the box being vacated. The area around the far post is usually vulnerable to chip balls in behind the furthest defender.

https://streamable.com/zxrwh

Full footage of Canada versus Jamaica available on YouTube.

Canada’s professional teams

At the moment, there are only seven Canadian teams that play in professional leagues within the North American system. There’s no direct regulation for the number of Canadian players required in the roster as US Americans also count as domestic players. According to transfermarkt.de, only 22 of the 87 players, or roughly 25%, in the rosters of the three MLS teams Toronto FC, Vancouver Whitecaps and Montréal Impact are Canadians. Adding to that, most of them are not even starters or regular members of the game day roster, which reduces the Canadian influence in the MLS to a minimal degree.

If you add the USL teams Ottawa Fury, Toronto FC II and Vancouver Whitecaps II as well as NASL team FC Edmonton, the ratio goes up to 47.33% (80 of 169). This is mainly due to the two reserve teams, that include more domestic talent, which is often neglected in the further stages. Without them, there’s a ratio of 38.7% (41 of 106) Canadians in the professional senior teams, which is for example significantly less than in Bundesliga (47.5%), Serie A (46.2%) or La Liga (57%), even if you consider the small sample size. Only the English Premier League has a much lower percentage of domestic players: 32.5%.

With Mauro Biello (Montréal Impact), Jason Bent (Toronto FC II), Colin Miller (FC Edmonton) and since a few weeks also Julian De Guzman (Ottawa Fury) at least four of seven head coaches are Canadians.

Tactically, this doesn’t change a lot compared to the national team. You can observe many of the same basic flaws with a few more pronounced positives added.

Against the ball, there equally is a clear tendency towards man-oriented pressing systems, that leave exploitable gaps in midfield and within the back line.

https://streamable.com/r00x2

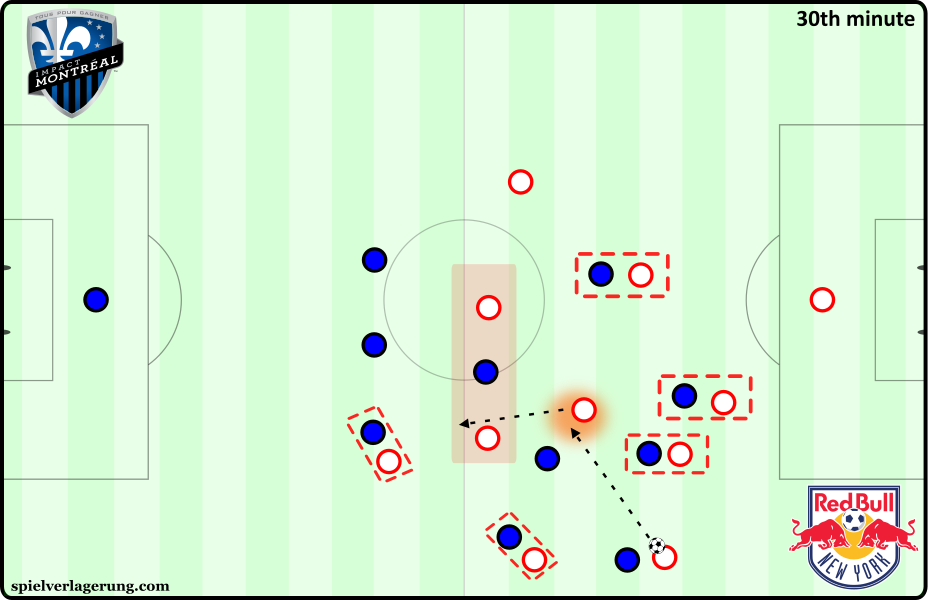

The New York Bulls have been one of the most interesting MLS teams ever since Jesse Marsch took over in 2015. You can still observe the typical RB style, playing the most intense soccer in North America with a focus on counterpressing and quick combinations, that prominently feature lay-offs. The structure has evolved from more of a 4-2-3-1 towards a back 3 with a diamond-ish midfield in front of that, with two wingbacks that can adjust their positioning fluently and one versatile striker upfront.

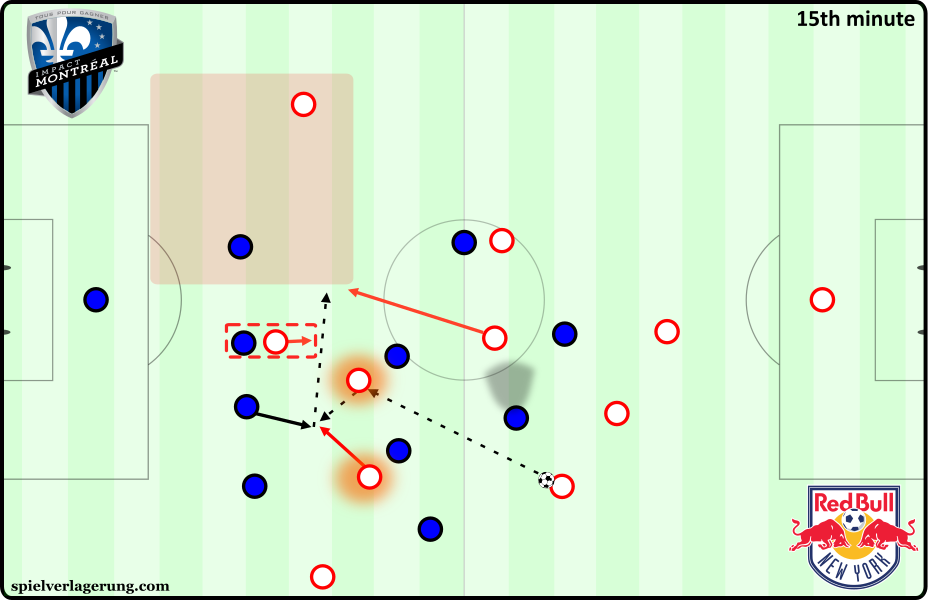

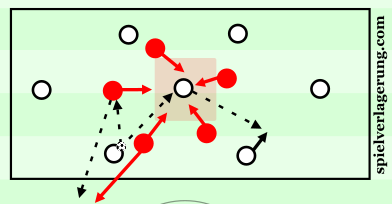

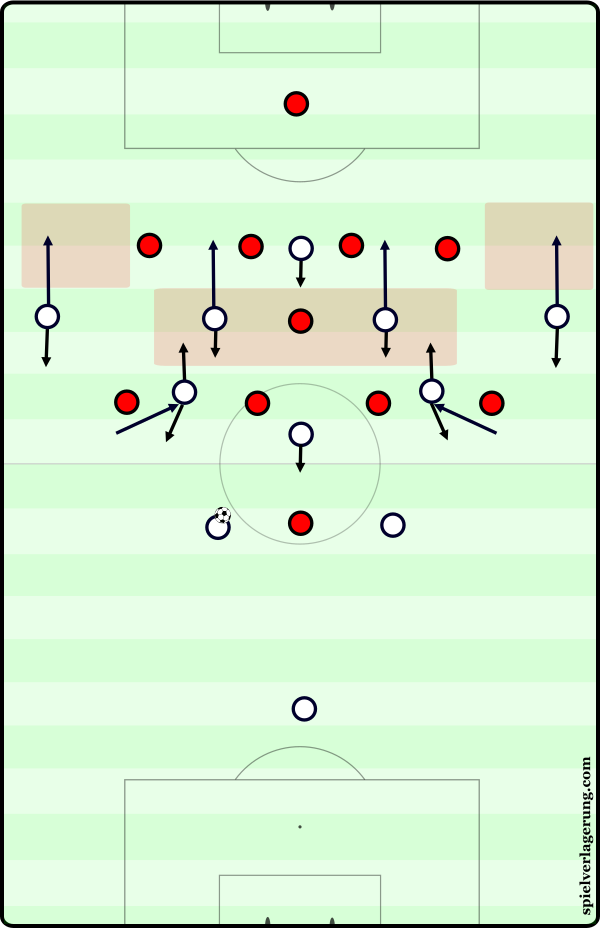

In the following graphic, you can clearly see, how their playing style can manipulate the man-orientations of Montréal Impact. The team from Québec tried to execute this pressing quite intensely, but struggled with the speed of the Red Bulls’ execution and couldn’t maintain their defensive actions for 90 minutes. This inevitably lead to a 4:0 loss for the Canadian side.

The problem with Canada at dealing with long balls was already evident. Interestingly, teams that operate with a lot of long balls have similar or even worse problems. The defenders stand alone and are again more oriented towards individual players instead of structuring themselves in a functioning back 4, that covers in a triangle for players pushing up.

Individually, the ball is often left to bounce in front of the defender or there is a failure to use the balls air travel time to get in front of the player. Instead, he pushes him from behind and causes free-kicks, often times from dangerous positions close to the box. When the opponent faces their own goal with no available options they are oftentimes not pressed the back line stays deep and the respective player can turn. An obvious pressing trigger is not used.

https://streamable.com/wj4xe

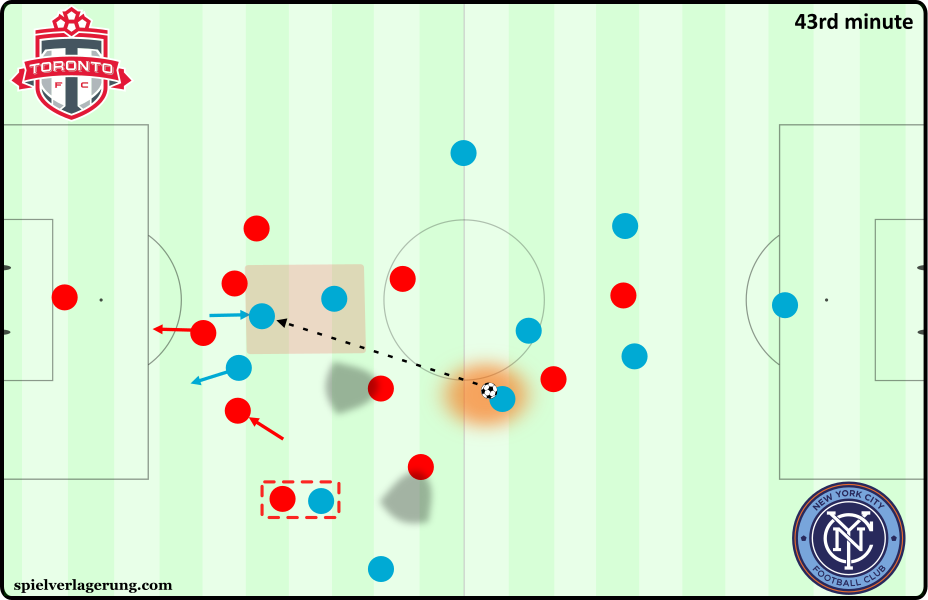

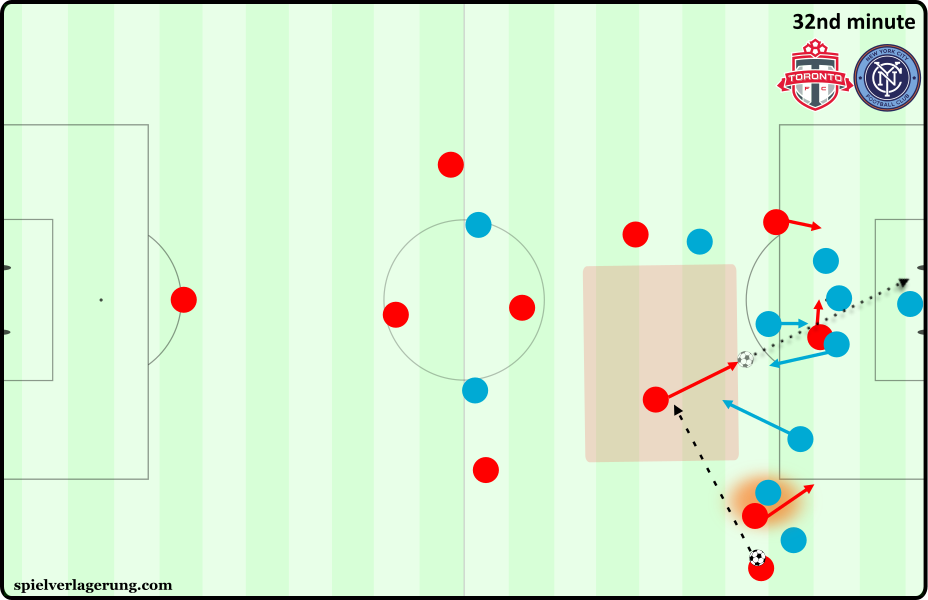

Different formation, same problems. Toronto FC usually plays in a 5-3-2 against the ball. This generally makes stepping out easier as you still have four players in the back to cover. Theoretically, also the central compactness should get better. On the other hand, the communication with five players can be harder than with four, especially when there don’t seem to be the same triggers that every player reacts to.

In this case, Andrea Pirlo has an open ball and is not attacked by any midfielder. The center back and the right half-back of Toronto already step back, the right wingback man-marks, while the orientation of the left-sided players remains unclear. Two players are free in the center. No problem for the Italian Maestro to pass to one of them. But a bad offensive structure of New York City FC prevents a breakthrough more effectively than any pressing approach.

The lack of collectively recognizing pressing situations is not only visible in situations, that are related to long balls, but also when it’s about pressuring opponents, that receive passes inside the block, in the access area of two or more players. Who attacks the ball? Does somebody need to do it at all?

Also, when a line of pressing is beaten, there’s oftentimes passivity instead of backwards pressing or shifting to provide cover. Result: Numerical disadvantages, frequently in wing areas, but also in more valuable central zones.

There’s a distinct habit to go back close to the own box, especially visible at the reserve team of Toronto FC, which plays in a similar 5-3-2 formation like their first team. Even in situations, when the team has clearly more players behind the ball than the opponent has upfront, team mates are constantly left to solve 1v1 situations against physically superior players, while there’s no clear zonal responsibility inside the box.

https://streamable.com/6dcwl

Felipe, the defensive midfielder of the New York Red Bulls, drops back to receive the ball and can dribble for a few seconds without being attacked. Sascha Kljestan and Daniel Royer position themselves in the gaps of the passive pressing formation. A pass to one of them provokes the central defenders to step out and to leave gaps. The Red Bulls play through to the far side, where the winger doesn’t participate in the pressing. Within a few moments, the game was carried from one side to the other. A 2v1 in the half-space close to the box is created.

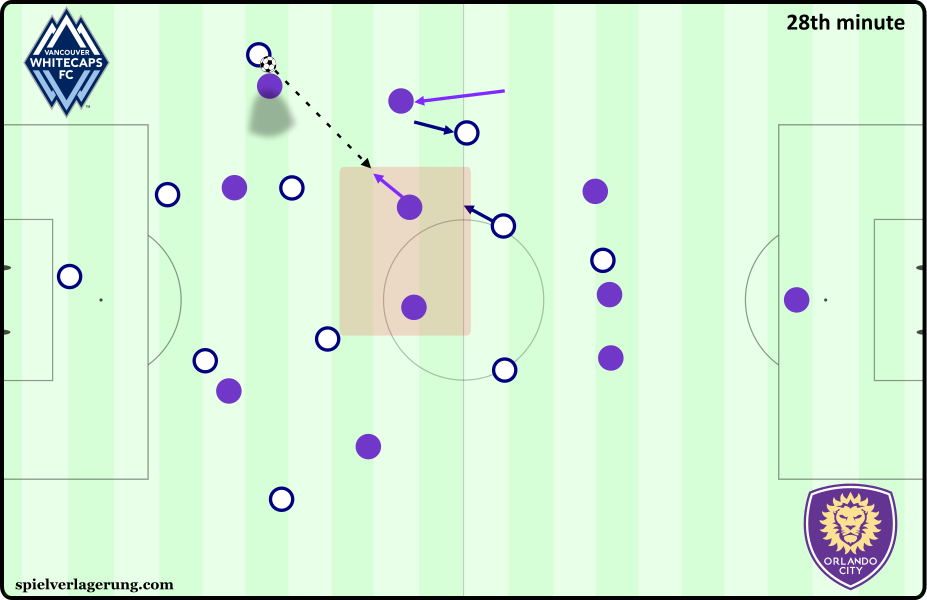

There are, of course, positives to take away from the analysis. For example, the reserve team of the Vancouver Whitecaps plays quite an interesting and centrally compact 4-3-3-0, that forces the opponent to play on the wing. There, the team of coach Rich Fagan, can ideally attack the ball from different angles. The team usually plays quite zonally in their orientations. A player from the second pressing line can push up to press the ball and will be covered by a player from the first line.

The Ottawa Fury with assistant coach Jed Davies generally show a clear pressing plan, using a 4-2-3-1 or 3-4-3/5-4-1 formation. They create compact situations in the wing areas to win the ball with many players around, who can directly be involved in securing possession or for counter-attacks.

https://streamable.com/qjuv0

A lack of pre-orientations (often linked to unfavourable body positions) is one of the most fundamental problems for a controlled possession based game. This leads to situations where the positioning on the field prevents progressive passes due to the unawareness of cover shadows, teammates on a communication level, and (group tactical) structure.

This is interrelated to a tendency where pre-planned passing patterns like long switches or balls behind the back line are chosen in favour of playing or creating better solutions from the situations themselves. As a result of those factors you can observe the same inconstancy in both the individual and of course the collective decision-making.

https://streamable.com/k9wmq

Another example of failed passing communication from the MLS team of the Vancouver Whitecaps. The team of Welsh coach Carl Robinson is lined up in a 4-2-3-1 with deep full-backs. The left one is in possession of the ball and has no options as the defensive midfielders stay in the cover shadow and the left center back doesn’t support. The central attacking midfielder drops for the ball, while the left outside midfielder pushes up. Both happen too late. The pass into the empty center can easily be intercepted.

On the other hand, there are enough examples where the players are able to play in tight spaces and under pressure – even when they are clearly outnumbered. It should be noted that bad orientation is not always due to a lack of player ability.

https://streamable.com/0wgrq

How Toronto FC scored against New York City FC: Right wingback and right central midfielder push the opponent back on the wing. The pressing is completely unstructured as Giovinco drops back to the space in front of the box, where he can receive the ball without being attacked. Afterwards, it’s unclear, whose responsibility that is. Arguably the best player in the league can dribble towards the goal and perfectly places a shot in the top corner.

As the graphic above demonstrates, the central zone which is of great importance is often poorly defended in North America. Against a compact pressing formation, the pass towards the center would usually not be the most effective way to directly progress the play. There’s much more manipulation necessary to create central space. But even with compact defending the first look still needs to be central to the one inside. If there’s space: Directly exploit it.

https://streamable.com/dg3ua

Half-back and wingback are already wide. Question 1: Why do you need to run outside? Question 2: Why should you play to a player running outside, when he just reaches the touchline?

Having written all of this there’s one thing that I should clarify. Long balls can be a viable way of attacking. If you use them in a smart way and have a good structure for second balls. This used to be the core identity of how RB Leipzig played, before Ralph Hasenhüttl and coaching staff took the game in possession to the next level. Long balls can still be used as a tool, however only if the situation is right.

The Ottawa Fury provide some examples of how this is also the case in the USL: numbers around the destined long ball zone, movement into depth. If you just kick the ball somewhere, you depend much more on individual runs and pressing efforts. If they fail, your attack automatically breaks down or you are exposed for a quick counter attack. Why should you play a long ball, when you are not well organized for rebounds and have a short option available with space in front of it?

https://streamable.com/8apfh

I also compiled moments, when the center is used properly, for example most effectively through diagonal passes on the ground, directed towards one of the half-spaces. When the opponent actually covers the center, you might chip the ball in behind the center backs or in behind the full-backs. Or you drag them out of position to attack the space for receiving through balls on the ground. With the ball being round everything is possible and passes in the air can and should also be used.

https://streamable.com/y4snk

The less connected the structure in possession, the harder counterpressing becomes. Especially when the players move to the last line and stay there after losing the ball. Then the attempt to win the ball back will become impossible as the outnumbered defence (players left behind the ball) needs to go back and faces a dilemma without support.

This problem of dealing with counter-attacks after the initial pressure is beaten, increases as defenders follow players instead of helping to condense the space in the center and forcing the opponent to the sides, where the attack would slow down and team mates could track back. In extreme examples, one player might even stay more than 10 meters behind everybody as kind of a “sweeper”, because there’s no communication within the back line of how to deal with counter-attacks, especially when being outnumbered.

https://streamable.com/byrhp

Full footage of USL/Canadian Championships taken from YouTube:

Ottawa Fury versus Toronto FC II

San Antonio FC versus Vancouver Whitecaps II

FC Edmonton versus Ottawa Fury

FC London: A practical example

The League 1 Ontario was established in 2014. The league usually runs from end of April/beginning of May until October. It is considered a regional third tier behind the professional American leagues. Geographically, most teams are based in the greater Toronto Area with teams from Windsor, London and Ottawa being the exception.

The main purpose of the league is to build a bridge between the long-term player development in the Ontario Player Development League (OPDL) and the professional side of soccer. Therefore, U23 players should play a special role: In the game day roster (of 18 players) there needs to be seven players younger than 23. The starting eleven must at least contain four players of this age group.

This still leaves space to include older players that played professionally previously and still want to perform on a higher level above and beyond the Sunday league. This is especially boosted by the semi-professional structure of the league. If you want to and have the resources you are allowed to pay players. Adding to that, you can include up to three international players, e.g. international college players, who want to spend their summer playing soccer.

Due to these regulations, League 1 Ontario can be seen as a very diverse league. Some teams entirely focus on playing young players for developmental purposes and without caring too much for results, as there is no relegation. Most famously, the third team of Toronto FC, which is basically their U19 plays in the league. Other teams use the minimum number of younger players and build their teams around ‘stars’ of the province in order to compete for the league title. The rest follow a mixed approach.

In the last six months, I had the pleasure to be part of the coaching staff at FC London, located two hours west of Toronto. The club already had its inaugural season the year before as Croatian coach Mario Despotovic did a lot of pioneer work as he lead his team to the league final and changed the whole club culture in the process. At the time of my arrival, there was no more discussion a culture had been set in place: Training should only be done in game realistic set-ups with opponents and the Periodization model of Raymond Verheijen was in place.

When Despotovic left to become the head coach of Hajduk Split’s U19 team in his home country, his compatriot Domagoj Kosic, a former professional player at Dinamo Zagreb took over. I was lucky enough to meet him right after my arrival and got to know one of the most open-minded, straightforward, and knowledgeable characters on this level. Everything, that the team achieved and will continue to achieve, happened because of him.

Without any prejudices, we started to exchange thoughts about the game right away. He saw David Goigitzer, Austrian author at Konzeptfussball, who coaches in the FC London Academy, and me as equal to him, even though in the eyes of most established soccer coaches we would have probably been just some random young guys, that pretend to be smart.

With this spirit, we faced the first challenges together. Many players of last year’s roster weren’t available at the beginning of the season. The players of the U21 team mostly came from other clubs and systems. There are no big possibilities to make selections. They still possessed a lot of (hidden) potential, but were without any idea of how to use their abilities tactically on a soccer field.

After the first successful season, our task was to work on the next milestone: Establishing a sustainable system with young players continuously coming through to play central roles in the League 1 Ontario team. Our asset: A highly motivated coaching staff and committed players, who are eager to learn.

We lost all of our first league games. The U21 got beaten by a team from the bottom of the league – 6:4. At the same time, the League 1 Ontario, was thrashed by Toronto FC’s third team in a 6:0 defeat. Probably one of the defining learning moments for myself, as I saw clearly as never before, how a game plan can generally work, but still fail in a dramatic way.

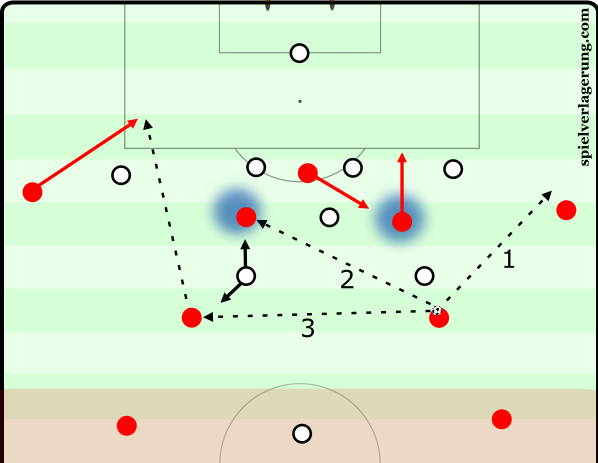

We analysed the opponent for weeks based on some games, that were played in a U19 tournament in Italy. Afterwards, we decided to press in a 3-4-1-2, that should guide the opponent towards the left side of their 4-2-3-1. There, our wingback was supposed to push up in order to win the ball. This worked well for 30 minutes. Although our ball wins were not clean enough, we created some favourable 2v1/3v2 moments, that weren’t used properly.

Then our high line broke down against the speed of Toronto FC’s young prospects. A threat, that we had underestimated in our analysis. After being 1:0 down, our structure to keep the ball was still intact, but the cover for transitional moments proved to be too unbalanced. Counter-attacks killed us.

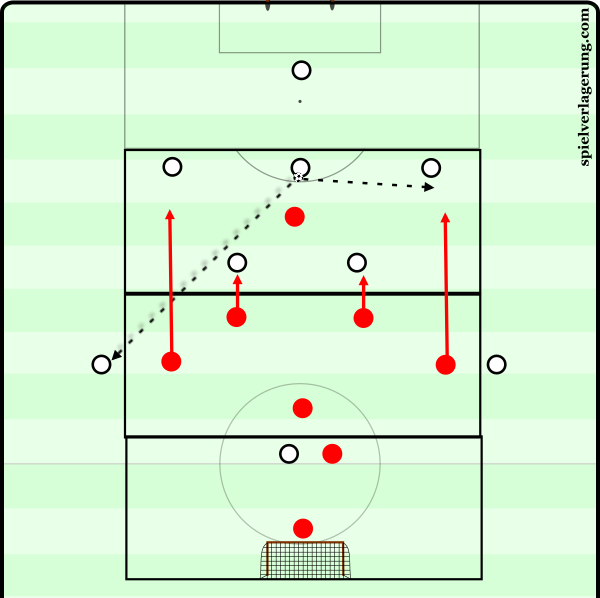

Nonetheless, we started the new training week, with the same spirit as usual after an extensive analysis of our shortcomings. The next opponent was supposed to be weaker and it would be easier to establish a controlled possession game to gain stability. Against the 4-1-4-1, that they used in the first league game, we would position ourselves in a 3-2-4-1 to overload the space around their defensive midfielder. In pressing, we would mainly take care of their long balls, sitting back in a 5-2-2-1/5-4-1. Most of the game was spend with us on the ball.

A key element for us was to create an effective relationship between the attacking midfielders and wingbacks. They were connected and covered through the defensive midfielders while at the same time getting support by the striker, whose basic task would be to drop back to offer a central passing option.

The main zone to break through would be one of the half-space with either the ball far attacking midfielder dropping or with somebody attacking the space in behind one of the opponent’s full-backs.

This was the starting point for our organisation of the coming week. A large part of planning process for training tactical awareness starts with being able to analyze the many possibilities that can occur from specific interactions during a game similar to what was done in the previous parts of this article.

Without this basic understanding, it becomes extremely difficult for the coach to plan their work. The analysis informs and shapes the way you will work. There is no such thing as a training methodology without analysis. They are interrelated and influence one another. JD offered a great example of an analysis leading to the creation of training exercises in a previous article, whereas RM provided a lot of invaluable insight on how to create a game model.

“During the defensive stage, I start analyzing the many possibilities that may occur. Then I translate them into a training exercise where there are opponents. Finally, I translate them into a game. During the offensive phase, I offer some guidelines keeping in mind what the opponents layout is. Here too, I follow the methodology mentioned above for the defensive stage, beginning with analysis. With Juventus, when we had established our identity I was using many theme games in practice. For two purposes: To give good motivation to my players, and not to annoy them with exercises regarding things they already know” – Marcello Lippi

The exercises should come from the knowledge of the coach and it should come easily to him from the analysis process. Actually, it is a big mistake to copy the work or training that is so accessible now through the internet. The art and skill of coaching comes from adapting your training to your reality and what you have analyzed. What we see and learn from others should be used instead to inspire one to create their own work.

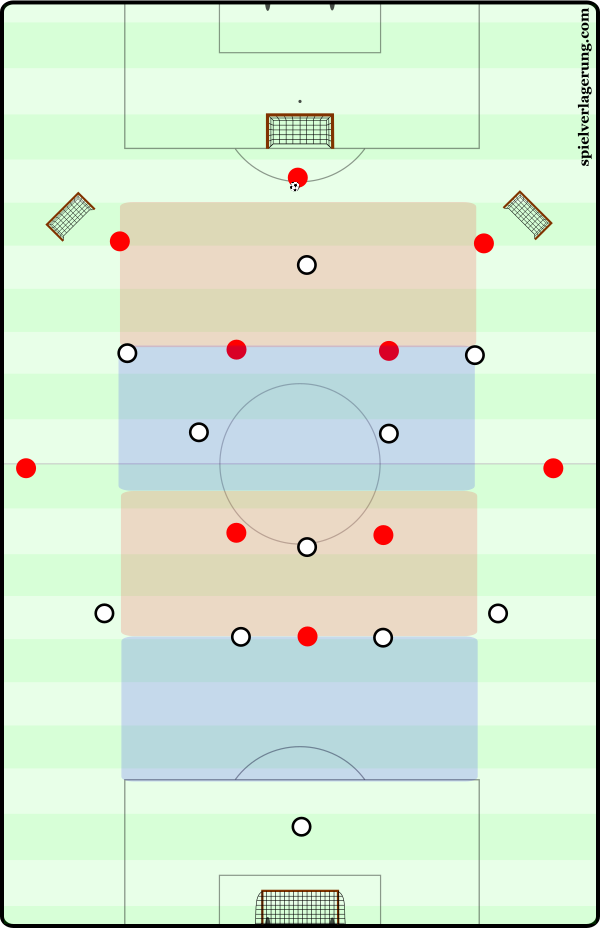

Our week after the game versus Toronto FC’s third team started with recuperation, that included specific tactical moments for the next game with an emphasis of playing in the last third. The attacking team was set up in a 2-4-1 versus a 4-3 block, whilst having a 2v1 rest defence next to the halfway line. The defenders were instructed to first defend rather passive and wide, then narrower. In the end, they became active. Different options of how to break through were presented to the players in the process, similar to the ones shown in the graphic.

Without having a consistent pre-season within the periodization model, we decided to not have a specific conditioning session with all players, until the roster would be complete in the week after. Instead, we managed the workload individually within the different game forms throughout the week.

These were based around playing in numerical superiority and transition to counterpressing afterwards. Situations of local numerical superiority were also linked to keeping possession of the ball beforehand, which was another big topic for the week. In this context, we would specifically work on how to effectively use chip balls and diagonal passes on the ground.

Training games used throughout the week

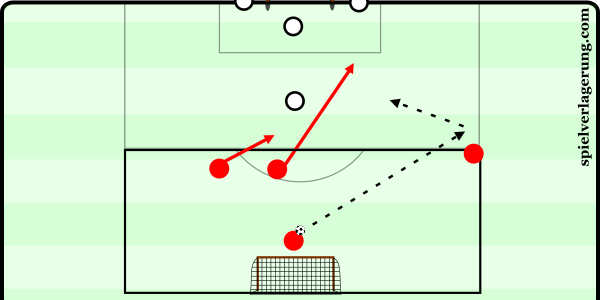

Game is played in the double the size of the penalty area. It always starts with one of the goalkeepers. He plays to one of the sides, where one attacking player is alone and not attacked. He brings the ball in the middle with a chip ball or with a flat pass and doesn’t participate afterwards. In the middle, two of his team mates play against one defender. If they score, the game starts from the beginning. If they don’t score (save, ball out etc.), two of the defenders from next to the goal come inside and start an attack together with their team mate in a 3v2. Once somebody scores or the ball is out, the game starts from the beginning.

12 players (split into 2 groups of 6 with teams of 3)

6 rounds

1 minute work for one group

1 minute rest

1 minute work for the other group

7v5 possession game on around 30*30 meters with a box of around 5*5 meters in the middle. Attackers score by playing 10 passes or by playing to a player in the middle zone, who plays to a third man with one touch. At first, there are no restrictions on how to occupy the zone in the middle. Later the player in the middle position must be constantly changed (if the ball is not played there for around 5-10 seconds). Defenders are not allowed to enter the middle zone until the ball is played there: 5 passes after winning the ball = 1 point or passing the ball out of the field (ball in the air allowed) to a team mate, that receives it there = 1 point.

6 rounds

1 minute work

2 minutes rest

Game always starts in the middle third with a 6v6+1 possession game (4-2 formation). After 5 passes the team in possession can progress towards the opponent’s goal through playing a pass to the end zone. There, a 3v2 is played until the ball is out or a goal is scored. Then the game starts from the middle, again.

5 rounds

2 minutes work

2 minutes rest

The whole field is used, but divided into three zones. 5 passes in every zone before progressing to the next one. Final zone: 5 passes before scoring.

10 minutes work including tactical instructions

The game starts with a 5v1 situation for the build-up team. Goalkeeper is not allowed to participate. After every 3 passes, the pressing team adds another player until they play in a 5v5 situation in the first half of the field. Then, the attacking players on the other half can come inside. Either the two attacking midfielders go next to the remaining defender inside the field or the striker drops back (defender is not allowed to follow). Attacking team then tries to score. If the defenders win the ball, they score on the opposite side. After every ball that goes out the game starts again from the first field.

6 rounds

2 minutes work

2 minutes rest

Build-up team always starts with the ball in front of the empty big goal. They play in a 3-2-4-1 against a 4-1-4-1 pressing. Put four zones inside the field (ca. 15m length each, penalty box width). The middle zones must be occupied by min. two players at all times whilst the occupation of the first and last zone depend on the situation and on how high the ball possession takes place. On the wing, there can be two players (half-back and wingback) when the build-up takes place in the own half, and one player when the possession is in the opponent’s half. Possession team can score normally on the other side. If the pressing team wins the ball they can score in the empty big goal (1 point) or in the two smaller goals on the sides (2 points).

3 rounds

5 minutes work

2 minutes rest

As usual in soccer, a few things went different during the game to what was expected beforehand. We still were in possession of the ball for most of the time, but the opponent defended with a bigger central focus, using more of a 4-2-3-1 formation. This changed the roles of our attacking midfielders from staying centrally to being more involved in the outside half-spaces and also moving more towards the wing. During half-time, we changed to a 3-4-1-2, once again, that helped to solve some of the problems. Problems in positioning of the wing-backs remained and were addressed in the video analysis after the 1:0 win.

For the next game, the home opener, we opted for a riskier approach with some players returning, that are more capable of playing different roles. We showed the team in short videos, how Pep Guardiola’s teams used inside full-backs to play in a 2-3-5/2-3-4-1 formation and focused more on attacking the spaces in front and behind of the opponent’s back line, whilst applying a more aggressive counterpressing in those areas. It eventually lead to a 4:0 win. But based on the type of game and opposition, we continued to also use formations with three players in the back or rather orthodox back four roles.

This process of adjusting to the circumstances continued throughout the season in a similar fashion like the example shown above. At the same time, some of the core principles of our game mainly the general rules of space occupation in possession and zonal defending stayed the same and became more established from week to week.

As the season went on especially the U21 team (a side mainly consisting of players born in 1999) became one with the game idea, as their own individual and collective characteristics helped to evolve towards a more direct style. This style will set the standard for a unique brand of soccer in London throughout the next years. With a much more pronounced focus on counterpressing and intensity against the ball, the U21 team for example beat Toronto FC’s U17 (born 2000) in an exciting fashion, scoring eight goals, conceding two.

At the end of the season more and more older players had to leave to fulfill other duties, mainly at college or university. U21 players that weren’t expected at all to do so, played full games in the League 1 Ontario team. In this time, we scored some of the best team goals of the whole year.

https://streamable.com/6xlhy

This is, why Jürgen Klopp famously said: ‘If we have a good idea, we try to bring it on the pitch, and that needs time. I believe in training, sometimes I feel I’m the only one in this country who believes in training, only others believe in transfers. I love this game because training can make the difference’. It doesn’t only prove to be true for players and the tactical communication on the field, but also for coaches or analysts, that try to go down that route. You learn something every day. Sometimes you will feel like a worse coach, but in the end, you can only be a better one.

Full footage of all League 1 Ontario matches is available on YouTube.

Conclusion

People tend to fear conflict and want to get some kind of consent. But there’s no consent between the prevalent way of “coaching” in Canada and actual coaching. It’s two totally different things.

As if you would have a conversation like this: “Let’s buy shoes” – “But this is a spoon” – “Okay, we’ll find some compromise”.

As outlined, there are enough problems to solve in Canadian soccer and that’s most definitely not a bad thing as long as the right attitude is adopted and there is a constant experimentation of trying new ideas, reassessing them, and finding more solutions.

If you are already the best, there’s little to improve. Then it becomes about the marginal gains and you need to look much harder to find the slightest growth areas. If you are 95th in the FIFA ranking, on the other hand some basic things should improve right away. If you begin the work immediately and with the youngest ages will begin to see small changes pretty soon. But over time they will continue to add up to become big changes. And who knows, maybe one day a culture will set in and Canada can be a consistent on the big stage.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Greg January 20, 2018 um 1:26 am

Great article. I want to congratulate on the ideas and implementing them.

I have some similar conclusions about Canada’s soccer after spending some time here.