The tactical trends of EURO 2016

As the competition has progressed, we have been able to witness a number of tactical trends shared by many teams in the tournament. Whilst there hasn’t been a particular pattern in terms of formations like we saw with the back 3 in the 2014 World Cup, there have been clear trends in marking schemes, attacking strategies and other tactical features.

In this article I will be taking a look at the two most prevalent themes we have seen in this year’s international competition.

Man-Oriented Defending

Orientation is one of the most basic actions in football, entailing how you act in accordance to certain reference points. From a defensive perspective, it is one of the most decisive factors in how a team decides to organise itself against the opposition. There are generally four reference points in football – the goals, the ball position, the opposition and your teammates. The ball and the goal are the two base orientations as the aim of football is to score by putting the ball into the opponent’s goal whilst stopping them from doing the same to your own. The opposition and your teammates are, on the other hand, more dynamic and complex.

If you’re wanting to learn more about the different orientations I recommend reading RM’s excellent theory pieces on man-marking and zonal-marking.

For example, if a team defends with a position-oriented zonal marking scheme, then their primary reference point for their positioning is the position of their teammates. They maintain their shape against opposition movement and act in a closed block without moving out to follow attacking runners. A prime example of this was Lucien Favre’s Gladbach side, or the current Villareal team.

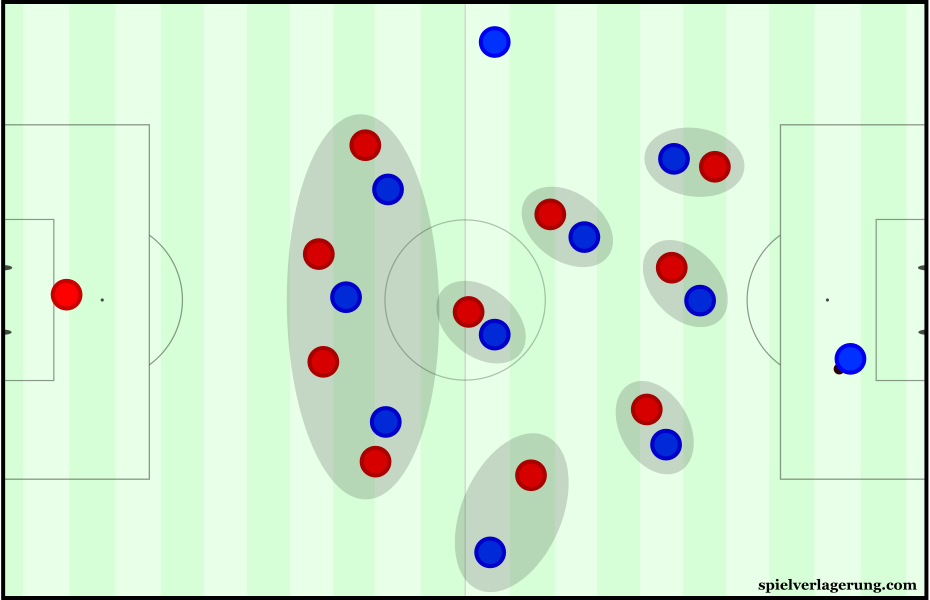

Throughout the EURO2016 competition, the most common defensive orientation has been the opposition’s positioning, or a man-oriented defence. When acting from a zonal base position with such man-orientations, this consists of a team marking zonally where the players will orient themselves to cover an opponent if they come within their space.

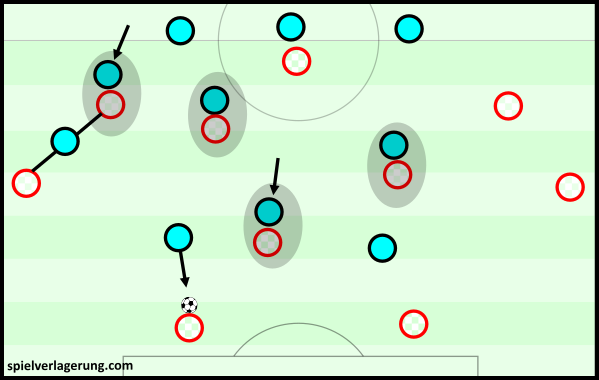

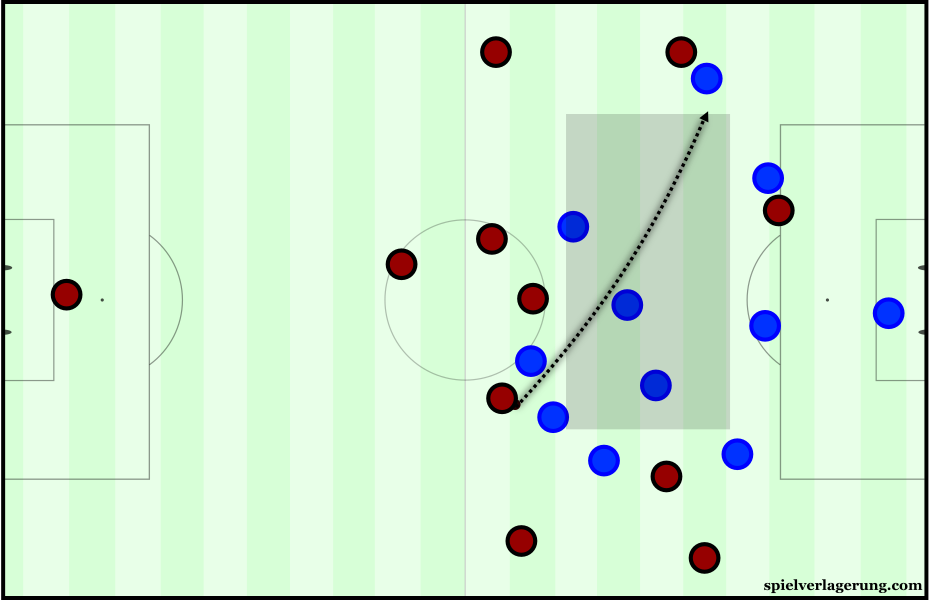

In the above scene, the ball is played to the right-back and the defenders react by covering any nearby players. The ball-near 8 positions himself to cover the opposition’s right 8 whilst the ball-far 8 is covering the striker in the middle. Whilst they cover the opponents in the centre, the ball-near winger moves up to close the ball down whilst the striker blocks access into the 6.

Note the key difference to the more rigid man-marking approach. Instead of following the individual players closely and standing on their feet, the defenders are flexibly positioning themselves so that they can cover the player without being on top of him. Because of this, they can maintain a more suitable defensive position and aren’t dragged out of position as much.

Compared to the more ‘extreme’ ends of position-oriented and man-marking, this scheme is somewhat of a medium between the different ways of defensive orientation. It allows a team to have a more consistent and stable shape compared to man-marking as their positioning isn’t as affected by the oppositions’. On the other hand, they are more able to press effectively than a position-oriented approach due to the closer proximity to the opposition players.

This flexibility is possibly a significant reason as to why so many teams have defended in this style throughout the tournament. A man-oriented approach can suit the needs of many team’s defensive strategies as on a theoretical level it allows them to maintain a stable shape whilst having access to apply pressure on the ball. It’s a fairly good mid-point between the two extremes of zonal and man-marking and (if executed effectively) can combine the advantages of both ends.

Aside from this explanation, a man-oriented approach allows a team to mask the negative effects of the minimal training time spent as a group. A more simple approach than something such as a position-oriented block, it requires a lesser level of cohesion and synergy from the players – something which sides have clearly lacked throughout the tournament. With players coming together for such a short time before the tournament begins, its very difficult for managers to have the players operating in a complex system.

Many teams, such as Portugal and Croatia have exercised these man-orientations out of possession. Against Spain, Croatia used the tactic to try and force 1v1 situations and challenges to regain the ball high up the pitch. By closely covering the opposition players whilst defending, Croatia were able to apply pressure individually and thus create unstable 1v1 situations which suited their plan. With a reduced ability to combine as a group, Spain weren’t able to make the level of ball circulation which they are famed for in order to work around the press. Croatia executed this defensive strategy effectively in their late win and came close on a few occasions after winning the ball within Spain’s third.

On the other hand, Portugal used this scheme in a more defensive-minded approach against Croatia in the first knockout round. Players covered their man in the midfield as they looked to block passing options into the centre and benefit from the above-mentioned defensive access. Through doing so, their pressure in midfield made it difficult for Croatia to play through their midfielders down the middle. In specific cases they took it further, situationally using man-marking to stop key players such as Modric and Rakitic from having their usual influence on the match.

Portugal covered their man closely against Croatia in order to restrict the influence of players such as Luka Modric.

Examples can be seen all over. In Iceland’s upset win over England, the two forwards positioned themselves flexibly when pressing to cover any passes into Eric Dier who was England’s lone 6 to begin with. Although it was done situationally, they generally wouldn’t directly mark Dier but instead maintain defensive access from close-by positions, giving them greater flexibility whilst able to intercept any passes into the gap in-front of the midfield.

In deeper positions, the narrow bank of 4 in midfield would adjust according to the presence of both Rooney and Alli and whilst the former was fairly dynamic in his movements, they restricted his influence in high positions whilst maintaining the defensive stability which significantly blunted the English attack. Through this defensive scheme, the minnows were able to keep a stable defence which rarely lost its shape whilst England failed dramatically to open spaces through the middle of the pitch.

Issues

Whilst some teams have had success when defending in such a manner, many teams have been largely inflexible in their man-oriented approach. The players stick to their opponent very closely and as a result can often be dragged out of position as the defence loses its shape and stability.

- Reactivity

One of the biggest limitations which comes with this type of defending is the reactive nature. When sticking close to your opponent and following his movements in defence, your actions are entirely reactionary as you’re copying what you see your man do. When taking a player’s reaction time into account, this can become problematic as it inevitably means that the defender is a step behind his opponent.

Obviously, an attacker knows his movements before he executes them and thus can make prior planning according to the contextual information and his tactical understanding. Meanwhile, a following defender must wait until the attacker makes his movement and he can then read the situation and take the appropriate reaction according to the context and his understanding. In this reaction time between seeing the attacker’s action and making his own reaction, the forward can gain valuable time which can give him the space to inflict damage. Although a footballer’s visual reaction time is fairly short, these milliseconds can make all the difference in tight situations, especially if Otto Porter ever decides to make the step over from the NBA.

Aside from the actual reaction time, the reactivity of man-marking is problematic as your defensive shape becomes determined by the opposition’s positioning. It’s a perfect invite to the attackers to destabilise the defensive block by dragging players out of position. If implemented well, then the flexibility of a man-oriented scheme means that this won’t happen against opposition movement. However, once the defenders start too-rigidly sticking to their man as has commonly happened in the EUROs, the shape can be lost.

- Flexibility and Individualism

Another issue if a man-oriented defence becomes too close to man-marking is a reduced flexibility. If a player so rigidly uses the opponent as his primary reference point, then it becomes difficult for him to account for other factors which require some extent of attention. Players can become focused on their assigned opponent and ‘tunnel vision’ reduces their ability to pick up on other important tactical cues which can instead go unnoticed.

A player’s fixation on his opponent means that he can often have a reduced ability to cover space, or switch onto another forward for example. This rigid defensive approach can lead to a robust nature for the individual player as he is assigned an opponent and no more. If his responsibility is simply to follow his man and stop passes into him, then the defender will not be able to effectively cover space or teammates when its required of him.

Another characteristic of a defensive approach too rigidly focused on the opponent is the individualistic nature it entails. Similarly to the above point, if a player is too focused on their own responsibilities then their ability to support teammates is lessened. This not only gives the defence a lesser level of flexibility, but generally means that inter-player support is difficult to make.

Contrast this to a better-executed man-oriented scheme and the differences are clear. With defenders flexibly covering their opponents whilst maintaining their position in the shape, they can help to cover open gaps or support teammates with their roles out of possession. As a result of this given flexibility, the defence becomes more adaptable against the opposition and can thus be more stable in maintaining control out of possession.

Situational/Specific Man-Marking

Alongside this man-oriented defensive scheme, a significant number of teams are also using situational man-marking to counter specific scenarios. When greater defensive pressure is required, a key opponent is needed to be followed closely or simply a more basic role is required of a player, this can be used to achieve any specific aims of the defending team. In the example I gave above, Portugal used situational man-marking in the midfield in order to stop Modric, Badelj and Rakitic from influencing the game.

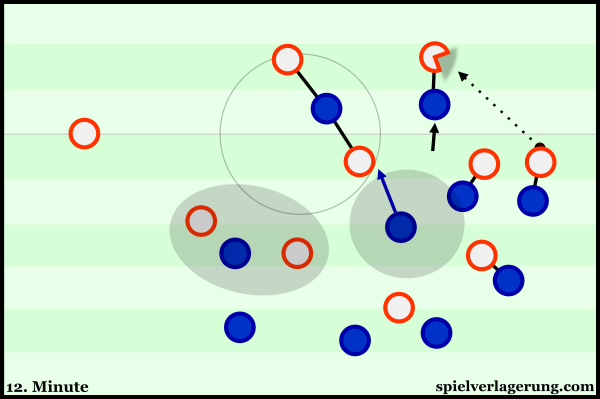

Many teams shift into a more man-marking-based defence when looking to press high up into the opposition’s half. The individual forwards cover a man each and they block any passing options for the player on the ball whilst pressing up the field with the intentions of forcing turnovers. In many cases they’re able to split the moment up into individual battles and isolate players away from the ball-carrier in order to disrupt the opposition’s build-up.

In a number of teams this is extended to the basis of some players’ entire defensive roles. Players are given specific responsibilities in defence which are outside of the collective scheme; whilst their teammates are more flexible, they much more rigidly follow their opponent in a man-marking style of defending. You’re most likely to see this in the wide areas in the role of the wingers, who are told simply to follow their opposition full-back and the runs they make down the touchline. If the full-backs are particularly attacking, it can often lead to the defence forming a 5 or 6-at the back with the wingers dropping into the defensive line alongside the their own full-backs.

Without the supporting presence of the wingers in the midfield zones, this can create quite an unstable defence which is weak centrally. Often taking up a 5-3-2 or a 6-3-1 shape, the defensive cover of the wingers (who would alternatively be in their respective half-spaces) is lacking and the central midfielders can become exposed without this help.

As a result of the lack of support from the ball-near winger, the defence’s coverage of the ball-near half-space is quite minimal. The central midfielder is often the only player occupying this zone and is therefore prone to become overloaded during attacks down this side. From the half-space, the attacking team can benefit from the greater time and space by making diagonal passes back inside towards the goal.

If both full-backs drop into the defensive line and a 6-man chain is formed, then the attacking team can look to exploit such situations with switches of play. By switching the ball from one half-space to the other, a team can exploit the uncovered space on the opposite side of the pitch due to the defending winger’s deep position. It is a good method of opening passing lanes as the defenders are still shifting to regain defensive access and through this they can break through.

In England’s clash against Slovakia, this was a common sight when Hodgson’s team had the ball within the opponent’s third. When either Bertrand or Clyne moved into advanced positions, their opposition wingers would follow them closely and drop back deep into the defensive line. Through this they enjoyed greater space in the centre of the pitch and dominated the game well, creating 2.1 expected goals throughout the 90 minutes.

Structural Issues

A common theme for many sides both elite and smaller in the tournament has been a weak level of spacing in possession of the ball. The positional structures of teams are often unbalanced with key areas of the pitch left unoccupied which has a harmful effect on their possession games. When in possession, players display the lack of synergy and understanding which is common at international levels and as a result, the level and quality of connections within the attacking structures are often insufficient.

Positioning is one of, if not the, most important parts of football and is crucial in determining how and how well a team attacks. Their structure should be suitable for their attacking strategy whilst allowing for some level of ball circulation at the same time. In order to effectively create and open space, a team generally needs to be spaced well across the pitch with good distances between teammates. Despite its importance, many teams have failed to do this in the tournament with a poor distribution of players across the width and height of the pitch.

Creating and Using Space

One of the key benefits of a strong positional structure is, as I mentioned above, that it allows a team to maximise the usable space. This does not mean simply stretching the opposition from both touchlines, but occupying the key spaces inside too. If there are wing-backs stretching but no-one offering in between the lines centrally then the advantage of width is largely wasted. By being spaced well on the pitch, a team can have strong connections between teammates whilst distancing themselves from opposition defenders in order to create space for the individual. Through this, a team automatically has a greater capacity to generate gaps between the opposition defence and in areas across the width of the pitch.

Although it goes without saying, such benefits means that attacking automatically becomes a more easily-executed process. Ball circulation is aided through the increased space for the team and the individual whilst the efficient spaces between players makes the actual movement of the ball cleaner and faster against the movements of the defenders. Through occupying varying horizontal and vertical positions on the pitch, a team is also more able to generate triangles and other shapes to aid combinations, as well as finding gaps between the lines of opposition too.

A side who particularly struggled to do this was Russia. One of the most disappointing teams in the competition, the side often left large spaces uncovered in attack which made for quite a dysfunctional side. With these gaps unoccupied, they obviously weren’t able to attack using such areas and not only did this result in a weaker attack, but it allowed the defence to focus on other areas too.

As a result of the sizable gaps left open, not only were Russia unable to use them but it also meant that their attacks were often disconnected. Without players in between gaps to connect the shape, possession could often be isolated on one side of the pitch with no way of progressively switching the ball.

In the example to the left, Russia have to resort to a long switch to an isolated area of the pitch because they have zero progressive passing options through the middle. With no-one to pass to within the Slovakian lines of defence, they have to try an ultimately unsuccessful long ball towards the left flank. With the striker poorly positioned, the full-back easily intercepts the lofted pass with his teammates providing greater support than his opponent’s.

Protecting the Transition

Another important benefit of a good positional structure comes after the ball is lost. With the opposition’s counters in the back of most teams’ minds, a strong positional structure is important in preventing or at least slowing any breaks from the opposing side.

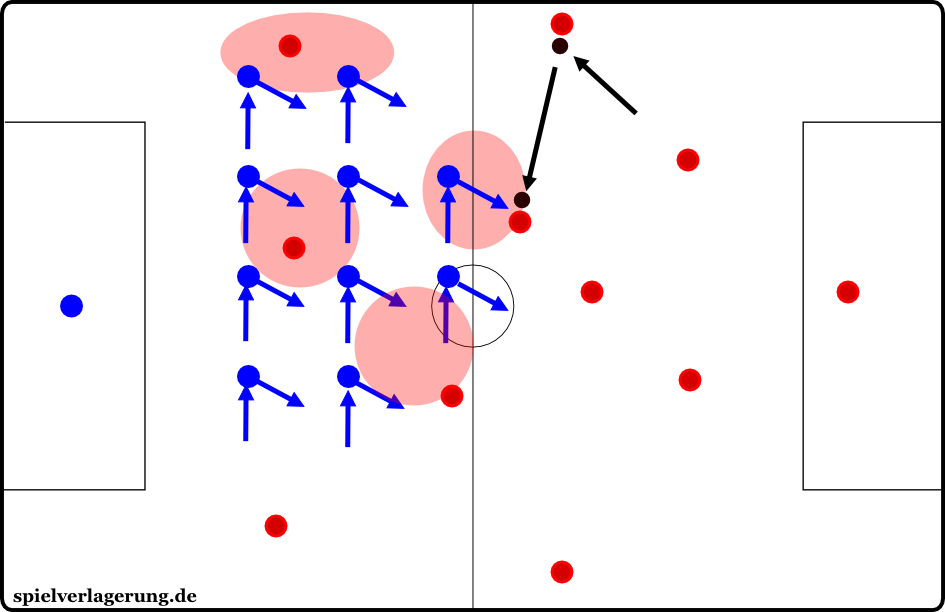

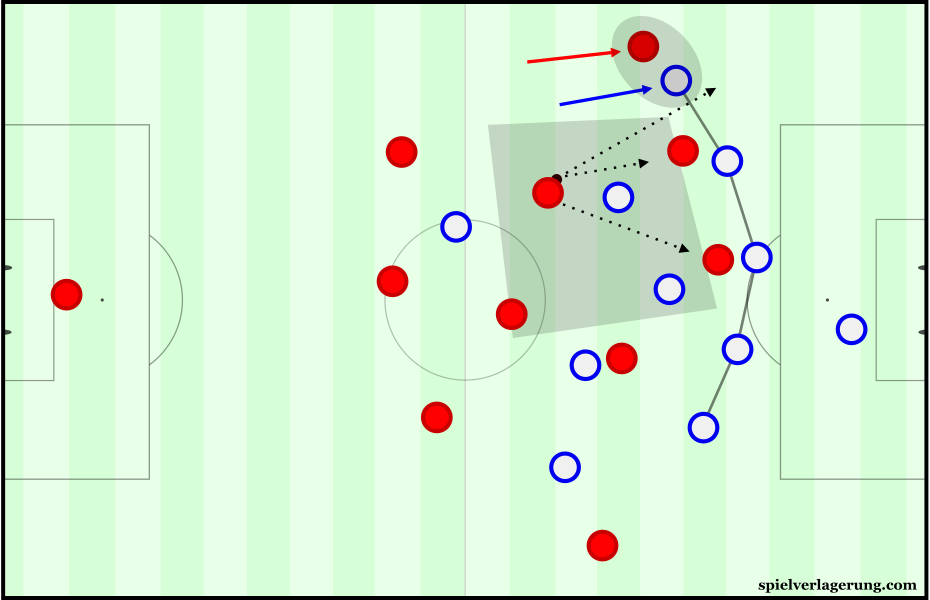

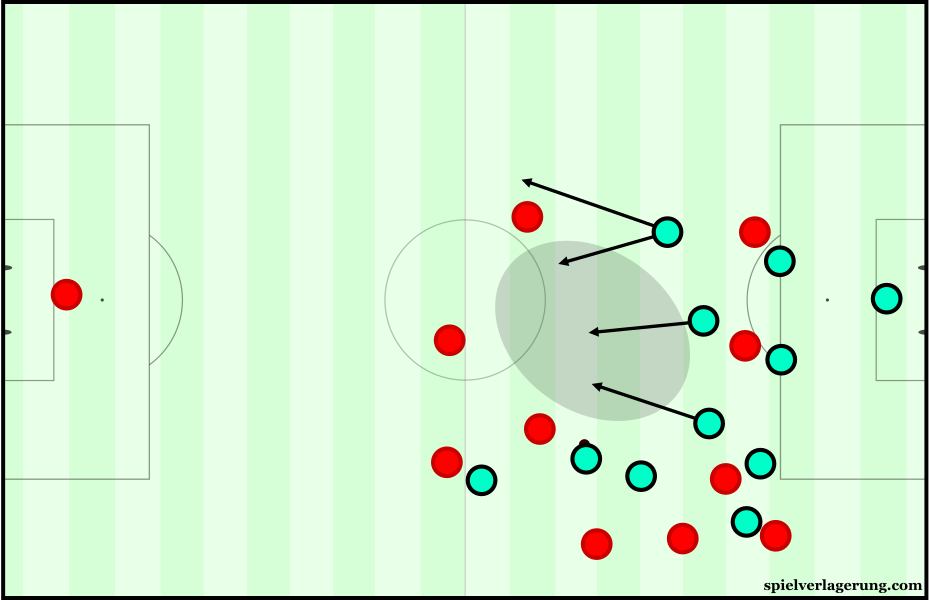

The concept is rather simple – if you have players covering the key midfield zones and spaces around the ball when you have it, then they will be in a good position to defend them if a turnover occurs. Surrounding the ball with players allows for a stronger counterpress to be made, whilst extra bodies covering the important midfield spaces means they can protect these gaps against an opposition counter-attack.

Having a strong positional structure with a high ball-orientation is important when it is time to counterpress after losing the ball. As shown above, the high number of players close to the ball means that one can apply greater pressure and as a result, have a higher probability of regaining the possession quickly.

Counterpressing itself is very beneficial from both a defensive and offensive perspective.

The immediate defensive pressure can work as a means of slowing any opposition break. By pressing immediately once the ball is lost, a team can force the opposition away from their own goal and slow down any potential fast break. Through covering any immediate forwards passing options for the ball-carrier, the now-defending team can stop their opponents from being able to progress the ball straight-away after winning it and instead forcing either a less-effective dribble or a pass backwards. It can also be used to force a clearance (and thus a regain in possession) through the immediate pressure of the opponent. Because the ball is won deep within the opponents half, they are likely to not want to risk losing it again in such a dangerous position and will opt for a safer option in a clearance.

Moreover, once the ball is regained via counterpressing in higher zones a threatening counter-attack can be made. The opposition is often unstable as the players have begun to move forwards in order to support the counter. Because of this, the counterpressing team now have open spaces to attack into after regaining the ball in an already advanced position. Liverpool coach Jürgen Klopp has described counterpressing as “the best playmaker in the world” due to the offensive potential found in pressing upon losing the ball.

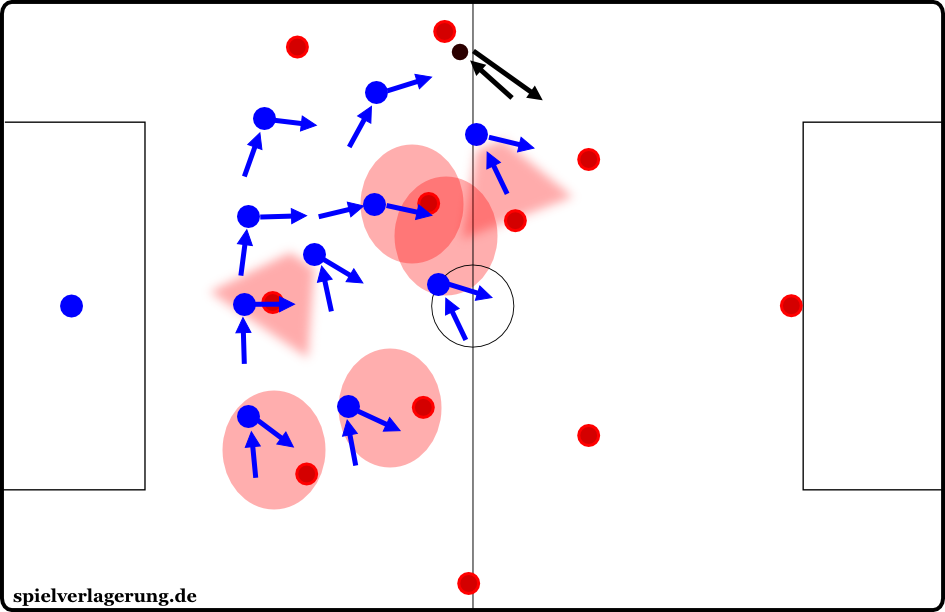

Hungary were one of the many teams throughout the tournament who often failed to counterpress effectively, and not least in their heavy defeat to Belgium. The main reasoning behind their inability lay with their weak positional structure when in possession, which then translated into a weak position to counterpress from when inevitably turned over the ball. Not only did their attack carry little threat without strong links through the attacking shape, but once they conceded possession, their midfield was open too. Due to their disconnected shape, the fast attackers of Belgium were able to quickly break into the upon gaps upon regaining the ball.

The scene to the left is a prime example of Hungary’s shortcomings in their 4-0 loss to Wilmots’ Belgium. The Hungarians’ cover of the centre of the midfield is almost non-existent and after unsurprisingly turning the ball over, Belgium immediately have inviting space to break into.

Player Integration

A third key factor of a strong positional structure is its importance in getting the most out of the players within it. Nearly all things in football are aimed in one way or another to maximise the actual players’ capacity to execute an action. In terms of spacing, it is often a matter of creating space for the player, or putting them in a position on the pitch which best suits their skill-sets. For example, a player such as Mesut Özil is one of the world’s best in the central attacking midfield position. From this area he has strong access to other areas on the pitch and is better positioned to connect with other forwards as he does so well. However, if you put him on the touchline, he suddenly has less space, is more isolated and the chances are that there will be fewer teammates within his reach.

A large part of football is down to putting the players in a position to succeed and this can often be done as part of a larger-scale positional structure. Although the act of ‘putting round pegs into round holes’ is a rather simple one, it isn’t always done on the pitch, as we saw in this tournament. Without the players acting in their favoured spaces, their ability to shine and influence the game won’t be seen at its full potential. An example of this can be seen in Wayne Rooney, who was commonly positioned as the second deepest midfielder during English build-up and the excellent player wasn’t able to use his skill-set to maximum effect so far away from goal.

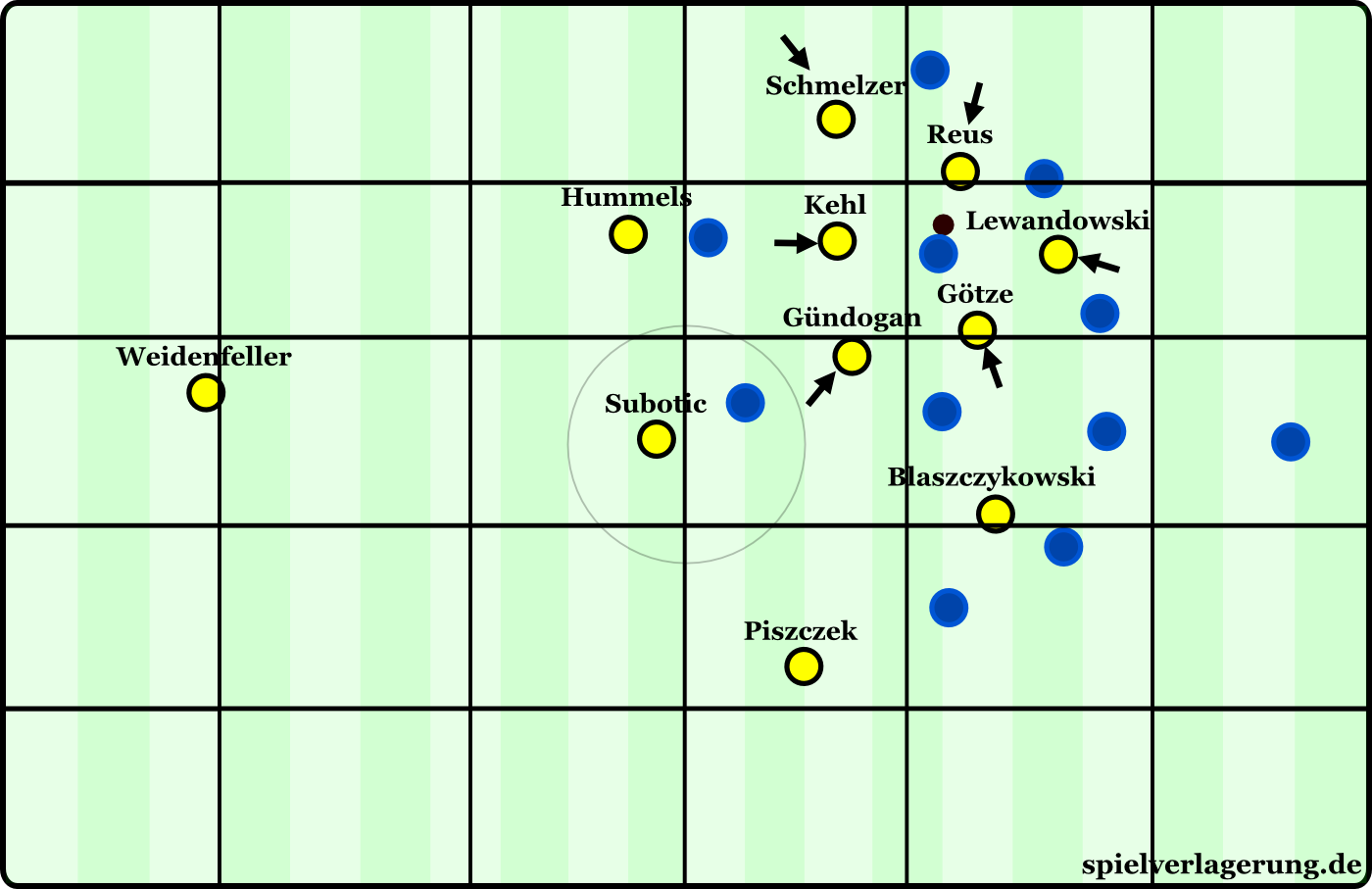

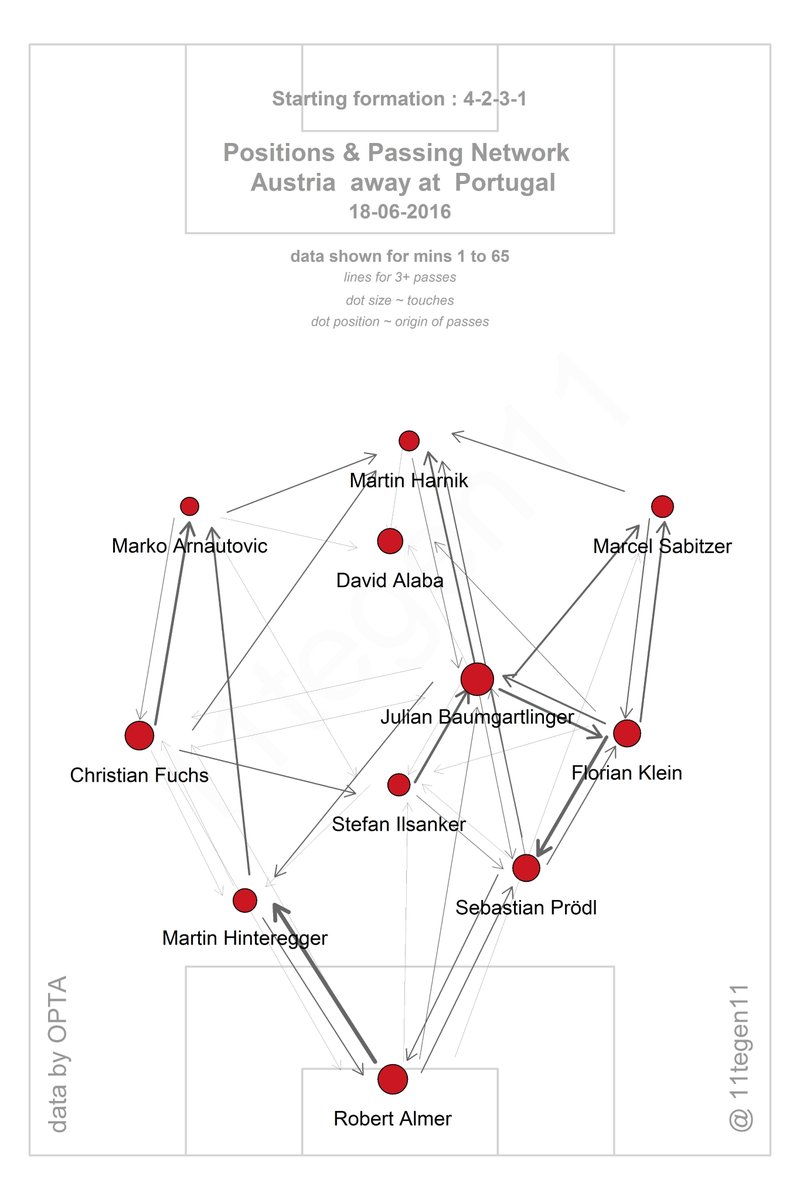

Another team who were weak in shaping themselves in possession were Austria, who despite possessing a talented squad were one of the most underwhelming sides in the tournament. The star of the team David Alaba, had a particularly poor tournament and was especially absent in their loss to Portugal. Far away from his more natural deeper role, the Bayern player is one of the most versatile in the world yet struggled as a 10 in this match. Although alternative factors were influencing, such as the team’s disconnected attacking shape and direct play, the midfielder struggled in an advanced position.

As illustrated by the graphic from @11tegen11, Austria had a stretched shape which saw many direct passes from deep positions. With Alaba isolated and unable to influence the build-up, he wasn’t as impactful as he could have been whilst he became rather anonymous higher up the pitch. Although he saw the ball to some extent, he rarely was able to successfully continue the attack which was largely due to the direct nature of the passes and defensive pressure.

Aside from Alaba, both Marko Arnautovic and Marcel Sabitzer were constantly too wide to either support teammates and be an active force on their own. The front four were all noticeably stretched in attack with the width of the pitch covered yet no connections across the front-line. Pair this with the vertical disconnection as a result of the deeply-situated Ilsanker and Baumgartlinger and Austria unsurprisingly struggled to formulate meaningful attacks.

In some ways, the Austrian positional structure is representative of their attacking strategy. They commonly looked to build in a direct and vertical manner with lots of direct balls being played into the front four, which somewhat explains the sizable gap between the two pivots and the attackers. However the positional structure nonetheless had a significantly negative impact on their play. The vertical distances were often insurmountable even with their direct passing whilst the front four were too disconnected to enable the side to consistently challenge for knock-downs and the second balls. When they did concede possession following these long balls, the disconnect in midfield meant that effective pressure in the counterpress was also difficult to generate and the opposition could start developing possession themselves.

Creating Situations of Superiority

A final key factor of a positional structure is its ability to create situations of superiority for the (in this case) attacking team. With a similar level of importance to the above areas, it’s another major aspect of spacing and football in general. If the attacking team can create a moment superiority in any way, then they obviously have an increased capacity to cause defensive instability in this scene.

Numerical superiority is one of the most commonly and most easily formed levels of superiority through a positional structure. It largely consists of creating overloads in certain areas of the pitch which can help the attack break through – often by finding the free man who is the extra in a ‘4v3’ for example. Often in areas close to the ball, a team can look to focus its shape to create an overload in these spaces. By doing so, they have support around the ball but also can potentially outnumber the defenders and, as long as the players are distanced well, a player is likely to be open. Spain are a team who did this often in the left half-space, with Silva often coming over from the right to act as that open player.

Another way to create such profitable situations is by emphasising the individual qualities of the players. Whilst this can be done as mentioned above, by fitting ‘round pegs into round holes’, it can also be exaggerated through creating isolation situations. By creating a 1v1 moment, a team can more purely (in that there are less influencing factors on the moment such as teammate support) pit one players’ individual attacking ability against an opponent’s individual defensive ability. Obviously, if the attacker is notably better than the defender, then this creates a beneficial situation for the offensive team.

‘ISOs’ are commonly utilised in basketball, when the attacking team has a mismatch. This can be done when a smaller, more technical player (such as a PG or SG) is matched up against a larger and slower defender (PF or C). During such an isolation, the attacker can use his strong ball-handling ability to exploit the big man’s lack of mobility and qualitative superiority is created through the mismatch.

An example of such an isolation was seen in the build-up to Germany’s second goal against Slovakia. Löw’s forwards often looked to use this strategy in order to emphasise their superior ability to that of their Eastern European opponents. In this case, Draxler moved towards the byline and through doing so created a 1v1 situation with his defender. From this, he used his strong dribbling ability to beat his man and open space to make a short cut-back for Mario Gomez who doubled Germany’s lead.

https://vimeo.com/173696867

Considering that spacing is such an important factor in a football match, why was it that so many teams struggled to have an effective positional structure?

Training time and non-verbal communication

One explanation for the teams’ downfall is their lack of training time together. With just a few weeks preparation after the curtains are drawn on the domestic season, it’s very much possible that the teams just don’t have enough time to train their spacing. The concept can be complex in many cases and the fact that it often involves the entire team makes cohesion, something rare in international football, almost a necessity.

It’s no surprise that teams such as Germany, who have numerous players who play for, or have played for, the same club are one of the best positionally. They show levels of non-verbal communication which is lacking across the rest of the tournament as players show a high level of understanding with one another.

This suggestion also has evidence in the development of teams over the course of the tournament. Whilst France were somewhat disappointing on the opening night with a poorly-shaped attack, it was their dynamic spacing which was key in their quarter-final demolition of Iceland. With teams improving over the short-lived competition, it could well be that their cohesion is increasing and the non-verbal communication is of a higher level and their collective positioning improves with it.

Although not in the EUROs, one of the biggest exceptions to this issue is Chile. However, once you begin to consider the background of the team then it begins to clearly make sense. For over a decade now, the South American outfit have been playing a very similar style of football which was ingrained by Marcelo Bielsa. Because of the consistency of their style of play, their familiarity with the positional side of their style of play is much greater than the average national team. If you contrast this with many teams of the EUROs, who have inconsistent playing styles (if they have one at all), then the difference is understandable.

Fatigue

A second explanation for this issue of spacing is a physical one. The large majority of players are coming off of the back of a physically-debilitating domestic season and enter the tournament in sub-optimal fitness levels. Whilst this obviously has a direct impedance on their ability to perform, it extends itself to a collective issue too. With the decreased levels of energy, we often see players moving rather slowly off of the ball in a somewhat lethargic manner. Because of this, many teams make ball-oriented shifts (the act of moving in the direction of the ball, often horizontal to follow the ball circulation and maintain support) in a too-slow manner to maintain support in the spaces around the ball.

As a result of fatigue, players aren’t able to constantly offer the support and connections around the ball which they had done for their club sides. They can’t follow the movement of the ball which almost inevitably means that support to the ball-carrier will be lost during a possession.

Conclusion

Whilst both lack of training time and fatigue are explanations for the poor spacing we’ve seen, it is also a factor in what has been an underwhelming tournament. As is common in international football, the level of play was rather disappointing and lead to many dull and boring games throughout the tournament. The individual players themselves were hindered by a full season just passed as they came into the tournament understandably fatigued, whilst their play between teammates highlighted their lack of familiarity and training time to form a cohesive understanding.

Even in the final match, we saw two teams with distinct tactical flaws. Despite Portugal’s defensive block lacking stability with gaps opening due to their man-oriented nature, France were only able to truly exploit this late after the introduction of Coman, as their shape prior had been too dysfunctional itself.

Despite the low level of tactical play, we did see some success for the smaller sides of the competition. Teams such as Iceland and Wales were able to overcome stronger opposition through the implementation and execution of a clear and effective game-plan – something which many teams seemingly lacked. However, the tournament predominantly served as another example of how important team synergy and understanding is in the effectiveness of a playing strategy.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Peda July 14, 2016 um 3:31 pm

A good read and an endorsement for my personal observations!

However, I you mixed some things up in your passage about Austria:

“[..] The star of the team David Alaba, had a particularly poor tournament and was especially absent in their loss to Slovakia. Far away from his more natural deeper role, the Bayern player is one of the most versatile in the world yet struggled as a 10 in this match. [..]

As illustrated by the graphic from @11tegen11, Austria had a stretched shape which saw many direct passes from deep positions. [..]”

Austria didn’t play against Slovakia. He did play as a 10 against Portugal but that game wasn’t lost, we lost against Hungary but he didn’t play as a 10 then. So, what are we talking about? 😀

I’m very curious what happens to the Austrian squad after Fuchs’ withdrawal. I always had the feeling that Alaba wants to play in such an advanced role, even against the intention of the coach. But overall I think the critics are too biased by the results. Although they were underperforming heavily and lost a key player early in the first match, they were extremely close to eliminate Iceland – the nation, everyone is freaking out about these days. I don’t think that’s fair.