Arrigo Sacchi’s cultural revolution

In the early 1990s, the Italian national team were in a distinct crisis. To solve the tactical issues, the Federazione drew on the secret weapon of domestic Italian football: Arrigo Sacchi.

The former Milan coach replaced Azeglio Vicini, who had not been able to win the World Cup at home, in 1991. Making its début against Norway, a draw meant that the qualification for the 1992 EURO was definitively over. However, Sacchi’s real goal was to rebuild the Squadra Azzurra – and in the long term to succeed at the 1994 World Cup.

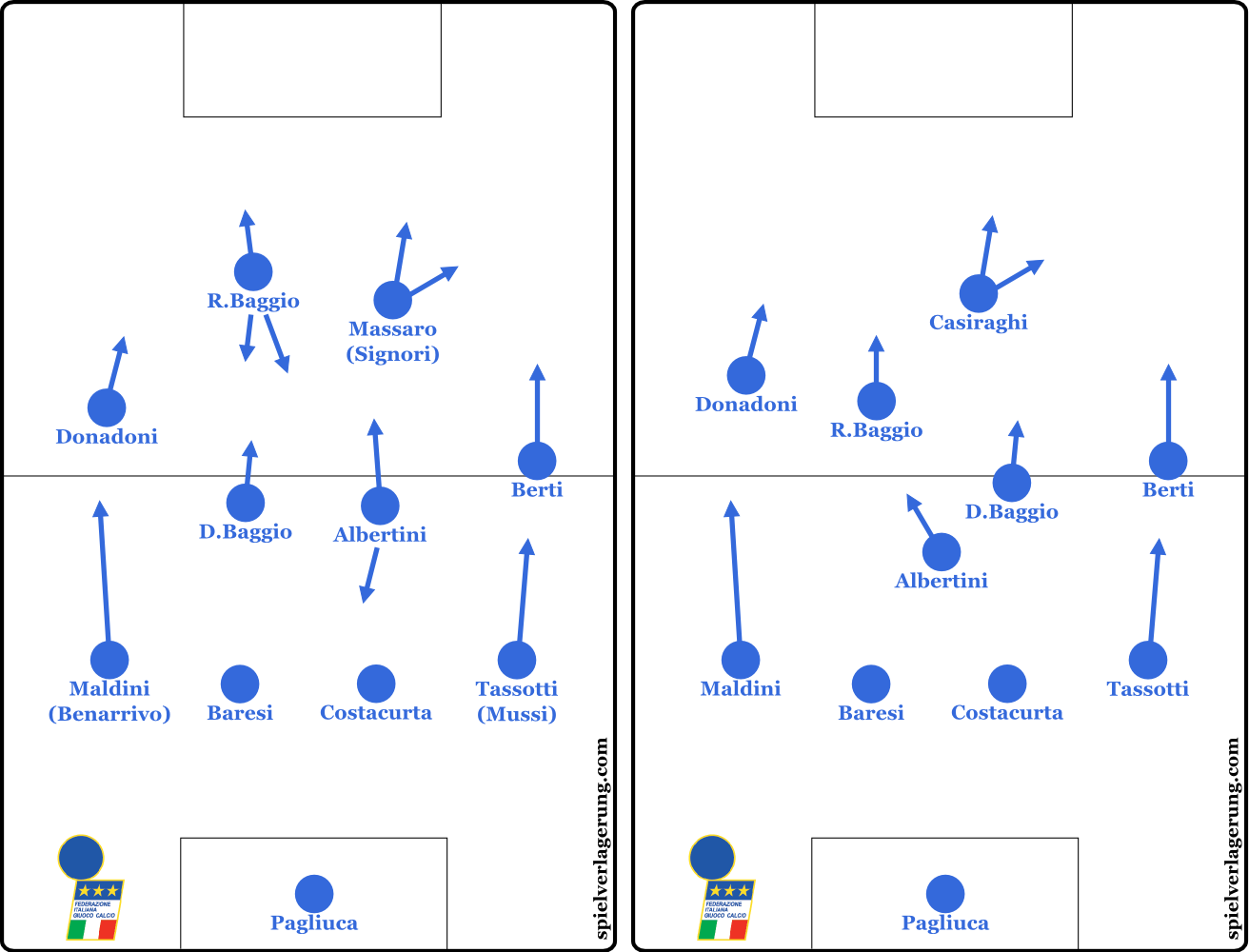

In that context, Sacchi relied on the well-known Milan axis composed of Paolo Maldini, Alessandro Costacurta and Franco Baresi. Meanwhile, the 1993 FIFA World Player of the Year, Roberto Baggio, was considered the pivotal point in attack. Certainly missing the qualities of his Dutch players from Sacchi’s Milan days, he was able to work on a coherent system, involving Baggio and the two Rossoneri Roberto Donadoni and Daniele Massaro. A system that, unsurprisingly, was very similar to the one Milan played in the late 1980s.

Sacchi, however, had to fend off his critics claiming he would prefer players from AC Milan, the club he had made his international breakthrough with. Internazionale’s Walter Zenga and Giuseppe Bergomi, Sampdoria’s Roberto Mancini and Juventus’ Gianluca Vialli would eventually not be part of the World Cup squad. Sacchi was at loggerheads with all of them.

A different interpretation: he only nominated players he could trust one-hundred percent. With a clear conscience, he depended on them holding up the pressing intensity in any situation. He asked for a defined greed to win the ball, and, more importantly, the will to dominate a game over the course of 90 minutes.

Reaching the final against Brazil finally underpinned Sacchi’s status and therefore justified his methods in the public eye.

He, moreover, proved that he was versatile, doing more than just putting his players through the mill of abrading exercises on a daily basis. He barely saw the Squadra and could only work with them during the international breaks. Plus, the nominated players were under the influences of their club coaches. It forced Sacchi to change his style. He could not teach any dogmas. He had to occur – more than ever – as a sympathetic teacher.

His well-known dry trainings and pressing exercises could only be applied during the immediate pre-World Cup trainings camp. Until then, Sacchi prepared all trainings sessions and tactical options meticulously. He thought through any possible formation for more than two years. With the utmost care, he observed the various types of players that came into question for his squad.

He and his assistants – including his former playmaker Carlo Ancelotti – masterfully planned the World Cup campaign. After losing against Ireland in the opening game in East Rutherford, the campaign threatened to become a disaster, though. Achieving a close victory over Norway and drawing with Mexico, Italy entered the second round as one of the best third-ranked teams.

They then beat Nigeria in dramatic fashion. Roberto Baggio scored the equaliser after 88 minutes, and later the deciding goal in over-time – from the penalty spot. Two more 2-1 wins over Spain and Bulgaria earned them a spot in the final. Pasadena’s Rose Bowl Stadium saw a sluggish final match in which only a penalty shoot-out could decide who became the new champion of the world.

Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi promised Sacchi a play in his cabinet in case of a victory. Later, Sacchi joked, Baresi, Massaro, and Baggio spoiled his political career. The Brazilian team featuring the likes of Dunga and Romário won the World Cup for the fourth time.

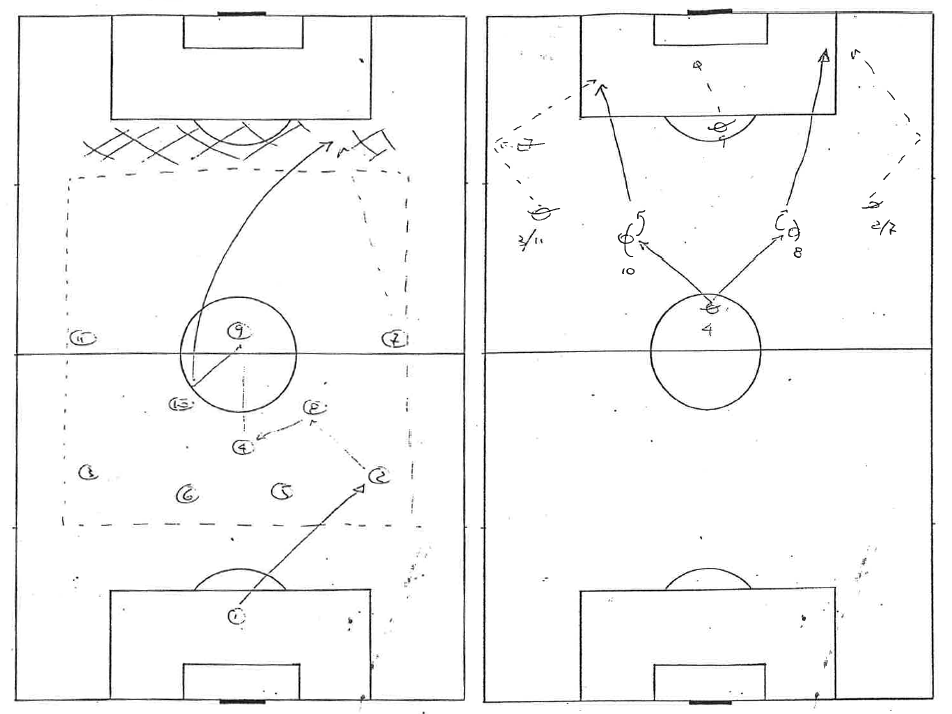

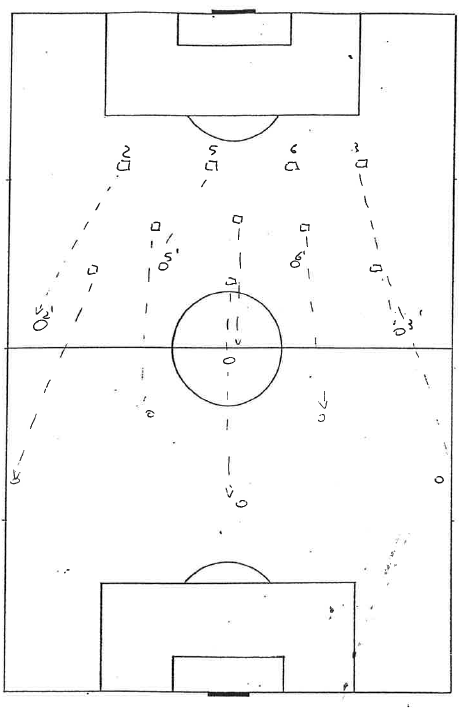

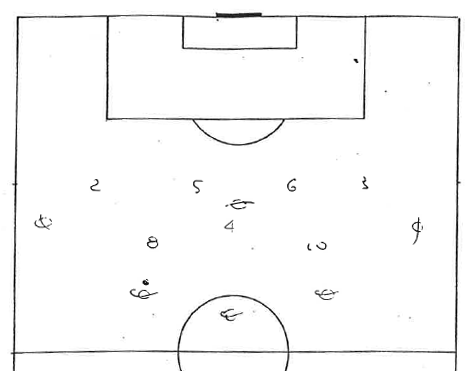

What were key elements of Italy’s successful side in 1994? Sacchi preferred 4-4-2 structures were essentially recognisable, although more fluid than in his Milan days. By tendency, the team played in a 4-1-2-3.

Sacchi involved all ten outfield players into his system of lines and chains. Roberto Baggio solely enjoyed a certain degree of freedom he understood to use. The striker occasionally dropped back into the zones between the opposing lines, picking up balls between the man-markers. Afterwards, Baggio shortly deferred the attack to either play a pass to his partner up front or a through ball to an advancing winger.

As soon as Baggio took command in midfield, the pass distribution out of the middle was akin to those two sketches by Sacchi. Being supposed to throw their man-markers off, the wingers should run diagonal routes. Apart from that, it becomes obvious that the ball-near number eight – Sacchi’s drafts mostly showed opening passes down the right side – was positioned deeper to serve as an open man.

Baggio’s movement therefore generated softened formation schemes. He roamed between a trequartista role and a number eight position in midfield. As a part of Italy’s second attacking wave, he often pushed behind the opposing back line, offering a deep receiving option.

From time to time, Baggio switched positions with Massaro or Giuseppe Signori. That kind of surprise effect was their ace in the hole. Furthermore, by constantly shifting the players, Sacchi automatically created dynamism within the formation and increased the pace when entering the opponent’s half.

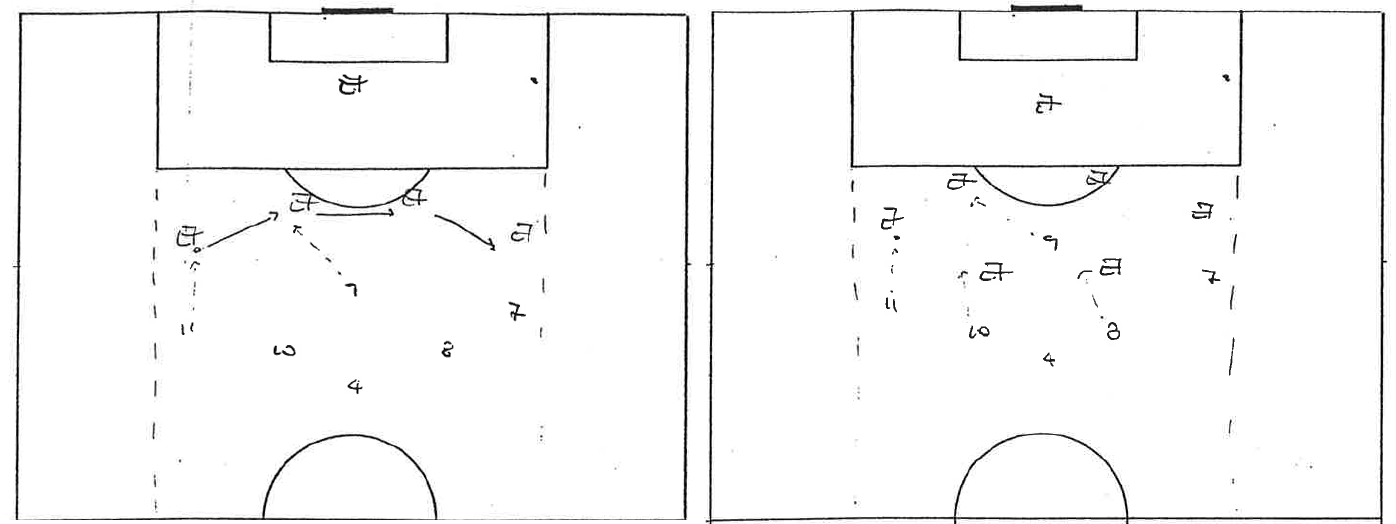

High temperatures stretched them to their limit in every match. Although Sacchi planned a high press as first pressing phase when trying to recover the ball, he was forced to occasionally give up the pressing ultraoffensivo.

That is how the pressing ultraoffensivo with a 4-1-4-1 should have looked. The ball-near winger’s advancing movement created a pressure wave which was maintained due to following runs out of the midfield.

In that case, the Italian team went back to the well-tried 4-2-4 formation and a rather customary chain mechanism, using variable opportunities to interrupt the opposing build-up play, while consequently collective deformations passed off smoothly.

In the course of retrograde movement, a 4-3 block tended to be an alternative to the usual two lines of four. The simple reason was, Italy wanted to use the speed of two attacking wingers up front in some matches. They tried to force an interception in the middle – the defending formation had to stand within a width of 44 yards – and afterwards aimed at utilising the close connections of a narrow 4-3 block to play quick and freeing combinations.

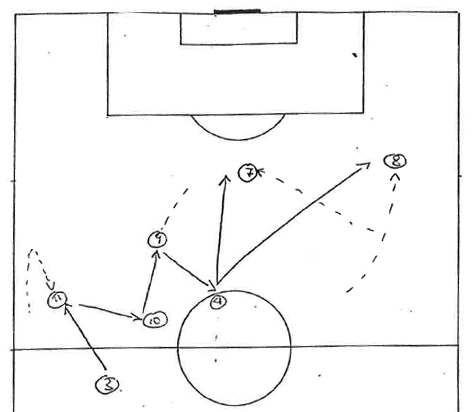

Italy’s combination plays were a widely underestimated component at that World Cup. The technically superior central midfielders, as Demetrio Albertini, for instance, had an eye for variations of short and medium-long passes, provided consistent gaining of space by creating triangles and playing precise lay-off passes. And moreover Italy kept the rhythm high. Cautious attacks did not suit the Squadra of 1994.

In that version, the left-back started the attacking play. After a short curl, the colleague in front of him offered a rebound pass. Meanwhile, the left attacking midfielder was dropping back. Afterwards he passed the ball on the striker in front of him. Those zig-zag patterns also involved the central number six who was supposed to deliver the ball out of the narrowing. In the meantime, the right midfielder was moving through the right wing zone, whereby a tactical trigger mechanism ensured that the attacking winger either pushed into the zone between the lines or ran behind the back line.

Sacchi’s side barely kept clean sheets. They multiply conceded one goal. As a consequence, their offense was even more challenged to outplay the opposing coverages with quick one-twos and lay-off passes.

As far as their defence was concerned, Sacchi had to permanently change the line-up. Although making a crucial mistake in the opening match, the experienced Baresi was nevertheless a libero-esque tower of strength. He injured his meniscus in the second match, though. Therefore, Sacchi had to move his interim captain Maldini to the middle. At both left-back and right-back, he then fielded more offensive types of players, so that eventual back threes became utterly rare.

Just in time, Baresi returned to participate in the final match against Brazil. Italy’s defence stood as solid as a rock during the 120 minutes. Sacchi pulled a variant form of the 4-4-2 pressing out of his hat. Defensively, the three ball-near midfielders moved towards the wing zone, creating a shortened chain.

Locally, the Azzurri squeezed the space as strongly as possible, yet the rest of the team remained loosely positioned. As a result, Sacchi’s team seemed to be robust against Brazil’s quick crossover passes. To move to the ball and re-create a reliable defensive shape, after the ball moved from one side to the other, Italy did not have to cover a lot of yards. In fact, the players, who were on the ball-far side, could rather stuff holes or stay zone-orientated in the middle.

Despite sometimes struggling in one-on-ones, Italy’s defenders kept the sheet clean against a talented Brazilian offense. The rest is history. Roberto Baggio, the Italian superstar and Sacchi’s best hope, misplaced the final and deciding penalty.

The career of Arrigo Sacchi has been uncrowned at international tournaments. Two years after the World Cup, La Nationale failed to pass the group stage of the 1996 European championship. His time as Italy’s national coach was over. Sacchi’s following career stations were also not spoilt by success. After disappointing months at Milan and Atlético, the Maestro threw in the towel.

“The accent today is on results, not on how well you work. You can’t build a skyscraper in a day, but you can build a shack,” Sacchi later commented on the fast-moving nature of today’s business.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Abdulmalik December 28, 2016 um 12:42 am

(Did’t read the article yet) But in your opinion what is the best match that Italy played under Arrigo Sacchi?

CE December 28, 2016 um 10:34 am

Probably their win over Bulgaria in the semi-finals.