In-depth analysis: Alfredo Di Stéfano

He is regarded as one of the first “total” football players, considered the grand master of his playing style and the prototype of a leader; playful, tactical, psychological. His name is Alfredo Di Stéfano – and he influenced generations of footballers.

Sir Alex Ferguson personally spoke of Alfredo Di Stéfano as an inspiration for him when he was as a child.

“They were incredible. They were the first truly international club team and they were fantastic “ – Ferguson, who sat in the stands at the legendary Champion Clubs’ Cup finals in 1960 when he was a boy.

In Argentina, the debate is not (yet) Maradona or Messi, but Di Stéfano or Maradona. And many of the older Argentines still see Di Stéfano in front. Granted, this may of course be a generational effect and glorification. After all, it wasn’t too long ago that many saw José Manuel Moreno and Adolfo Pedernera ahead of Di Stéfano.

“The best player I ever saw in my life, was Adolfo Pedernera. Undoubtedly, Maradona was exceptional, fantastic. The best in years. One can not ignore even Pele. But for heaven’s sake, though it is difficult to draw comparisons, Pedernera was a very complete player who could play anywhere on the pitch. “ – Alfredo Di Stéfano Viagra Generika kaufen in On…

Still, there was and is only one Don Alfredo. And there never will be another, because such a playing style is probably impossible today. This in-depth analysis will explain why this is so, and what made Alfredo Di Stéfano so special. His fundamental playing style and tactical nature in the team is described first, explaining the individual peculiarities of his technical style and also describing a specific psychological component. Besides repeatedly merging smaller quotes about this great player into the text, there is also a selective retelling of arguably the greatest European Cup game of all time, the 7:3 Real victory in 1960 against Eintracht Frankfurt. The graphics and statements come from visual search, if possible, and otherwise from text sources and descriptions.

A defensive nine as well as an attacking third and four-phase playmaker

6 minutes: Alfredo Di Stéfano gets the ball in front of the center line, carries the ball into the middle, but his outside of the boot pass goes astray. Frankfurt has the ball in midfield, Di Stéfano goes to counter press, but is dodged. The Germans play a long-range pass to the wing and counter. It comes to a cross, but Real’s defense clears it over the foul line. Marquitos has the ball – and plays it to Di Stéfano, who offers himself to receive the pass in his own penalty area and passes it with one touch. Canario plays to Marquitos, then back to Di Stéfano. He carries the ball through the midfield now, confident as ever. With the ball at his feet, he thrusts forward and plays a square pass that preceded a longer ball circulation for Real.

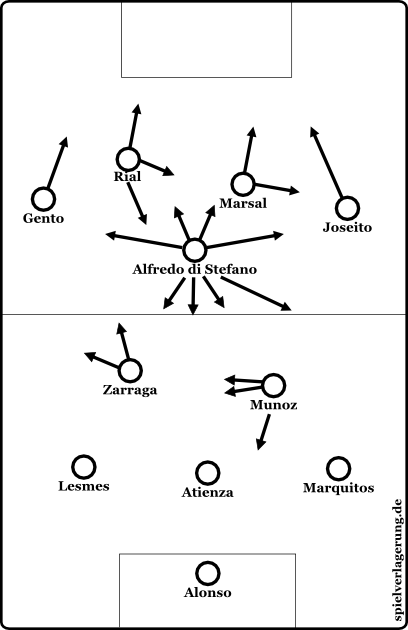

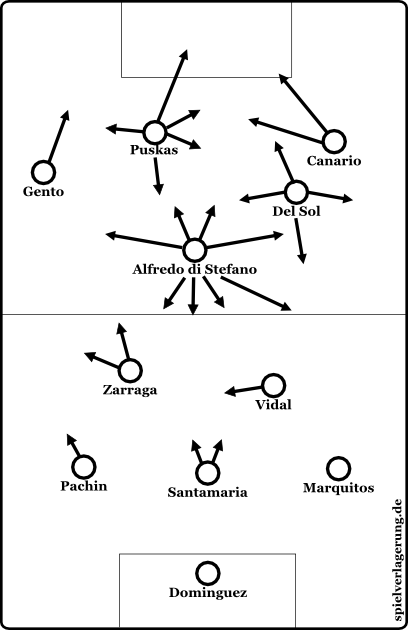

Real Madrid 1956

Di Stefano could play all of the central positions; center forward, second striker, ten, eight, six, central defender, libero. But he played them all simultaneously. As a center forward, he often fell back between the defender in the 3-2-5 to fetch balls directly from his own penalty area and then march forwards. With the ball at his feet, he used his game intelligence to open the game with long-range passes, dodge around spaces and enemy pressing movements with combinations, or simply dribble past one, two, or even three opponents.

“The great thing about Di Stéfano was that when he was on your team you had two players at any position” – Miguel Muñoz

These slalom runs as a defensive midfielder are often equated with his playing style; but that is a reduction of his skills and (even a negative) glorification of his archetype. Very often Di Stéfano is reduced to his goal threat from deep and merely supporting the midfield, but the Argentinian superstar of the 50s was much more than that. He could fill in as a deep playmaker in a variety of roles and styles, possessing the very rare ability to completely steal the game with his rhythm and dynamism and briefly take over a game.

It is often said of playmakers that they “set the tempo,”; yet it is rarely clear what that means. From a tactical perspective, one can imagine that the player is calmly engaged in a very dynamic game with many zone-changes and intense movements. Predominantly creating vertical attacks by leading a calmer and more stable ball circulation before directly or indirectly increasing the pace.

Too high a rhythm can also create problems of a tacticalnature (such as a more wide-ranging and demanding nature of the passing game, unpleasant game dynamics or hasty decisions) and a psychological nature (such as more hectic action in the team’s coordination or a lack of concentration and precision).

Of these various aspects, most players can only exert very little influence and control over the different spaces; some thrive on a fast rhythm, and find that, in general, they can only switch between fast and very fast or influence their environment at these speeds. Others are missing the middle range. They can either be slow or fast; and some may not even realize what they’re missing. To completely take over the pace for a brief moment and then flexibly revive it in varying degrees of intensity is an underrated art; and the “striker” Di Stéfano dominated them all.

“The Argentine was the smartest player I ever saw. Pelé was perhaps the better instinctive player, but Di Stéfano came onto the pitch and the game had been largely played out in his head. “ – Bobby Charlton

In some situations he broke away from opposing defensive efforts or dropped extremely deep into the build-up when it became vertical, and then stood with the ball. This sounds trite, but it had a certain effect: neither the ball nor the ball carrier moved and Di Stéfano had previously taken care that no opponent had access to him. Thus, a short break was abruptly introduced into the game; all previous free-runs or coverage movements could be completely reorganized. The cards were, in a way, redealt. Should someone dare to attack Di Stéfano in these moments, he now had a bad hand: Di Stéfano then usually twisted around his marker with a few touches to free himself, a la Xavi, and was able to interrupt his turn to make use of the resulting Dynamik if there was a suitable opportunity.

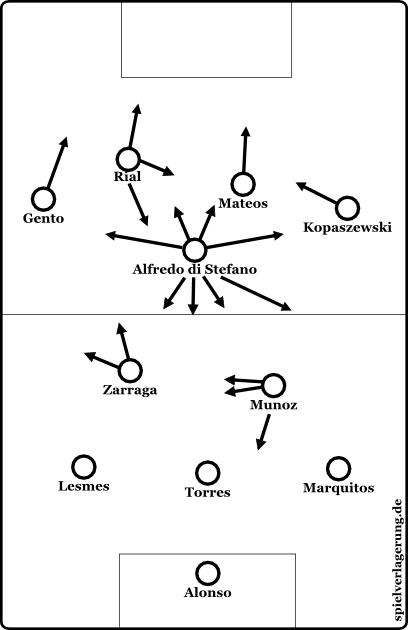

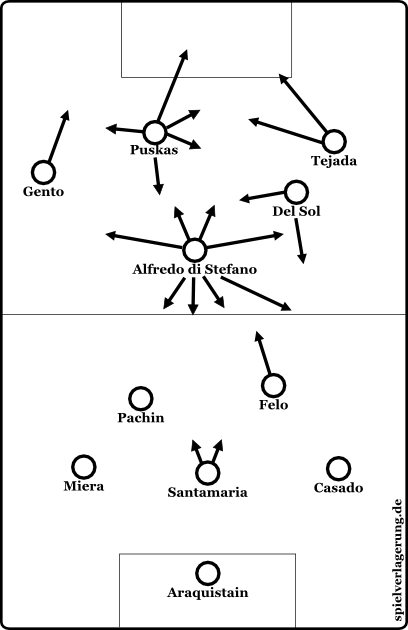

Real Madrid 1957

These short idle periods, however, were often only the calm before the storm. Di Stéfano was not only positionally complete, but also incredibly gifted. With fast dribbling in the open and strategically selected areas, he opened passing options, leading the attack with passes or combinations to the wing or looking for the pass himself on the way towards goal.

He also almost continuously altered his field of view. When one observed Di Stéfano in the game, they noticed immediately that he wanted to repeatedly reposition himself so that he could oversee the pitch completely throughout the match. His corrective ball control was sometimes a little messy, because he always pushed the ball over to one side and then slightly changed direction again. However, this also fulfilled the purpose of constantly looking for the best strategic solution.

Generally, Di Stéfano had a great sense of his surroundings, used his field of view very well and employed both to control the surrounding dynamics of the game. He also changed his physical stances and positionings very appropriately; adjusting not only his position, but his posture. Because of this he could respond more effectively and with greater diversity to demanding scenes, as he was already aware when receiving a pass of his potential options. He let hard passes, for example, successfully go to a teammate or switched intelligently between one-touch passes, short breaks before the pass (trapping the ball and making a short run) or an anticipatory circulation backwards.

Unlike many playmaking and influential attacking players (especially center forwards), Di Stéfano was therefore strategically outstanding. He sought not only the best action for the next step, but took into account his spatial awareness when making decisions. So he did not, for example, pass to the closest teammate, but to the next player, and commanded that it should immediately be played backwards; thus giving the second pass receiver a better field of view, more varied options, and more time for Di Stefano to move up front.

“Who is this man? He takes the ball from the goalkeeper; he tells the defenders what they have to do. Wherever he is on the field, he is in a position to get the ball. It is his influence on everything that he happens to see. I’ve never seen such a complete footballer. It was as if he had his own command center set up in the heart of the football game. He was as strong as he was subtle. The combination of his qualities was fascinating. “ – Bobby Charlton

The comparison with Cristiano Ronaldo which has been made a number of times in recent years is thus somewhat misleading; Di Stéfano shared certain individual aspects with Cristiano Ronaldo, e.g. physical dominance and presence, ambition, status, two-footedness and the goal-oriented awareness of movements in the penalty area. But, in his completeness he was much more of a Luka Modric, both tactically and strategically, who was also implemented as a penetrating and powerful center forward.

This goal-oriented awareness and awesomeness then expressed itself in his overly demanding and controlling (!) passing game; if there were no forward movements by his teammates, then Di Stéfano forced them. He deliberately played their passes a little further into their path, urging them forward, and offered himself up for one-twos. If it was too slow for him, he would send his teammate one way with the ball and another in a running challenge into the strikers – forcing extra space in a different way.

But, Di Stéfano was not only outstanding at commanding the passing game. He also had the useful ability to not always have to tear the game up himself, but also be passive and supportive. At the same time, he showed some interesting actions in his spatial movement, using spin moves, where according to his own passing game or an action from his team in midfield he ran behind, thereby opening himself up for a diagonal pass with a shifting effect. To do so he used arced runs, i.e. lateral movement with a circular run into the resulting hole – and vertical sprints into the strikers. Di Stefano dominated with evasive runs on the wing, breaking through along the side of the field or making diagonal runs into the half-space, cutting through very narrow spaces with extremely dynamic combinations or functioning as a needle player in the tightest areas in the middle and final thirds of the field.

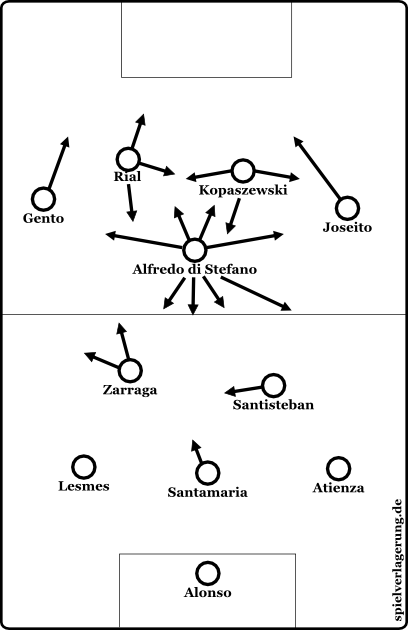

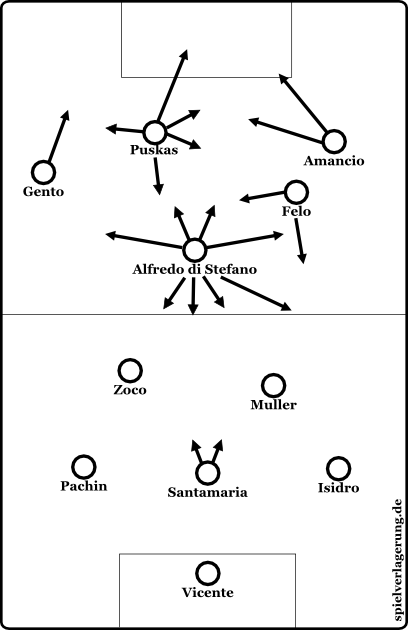

Real Madrid 1958

He garnished these moves again and again with sudden, explosive runs towards goal. These deep sprints in the final third were possibly the key feature of his style of play; he either opened the middle of the field for other players and the midfielders to move up or he could be played into the hole. He was particularly good at finding space for himself with his runs, possessing a great feeling for the next move. When he moved up, he rarely did so too early or at the wrong time, carefully choosing the right moment with meaning and purpose.

“Alfredo Di Stéfano was the greatest footballer of all time; much better even than Pelé. He was, simultaneously, the anchor on the defensive, the playmaker in midfield and the most dangerous sniper in the attack “ – Helenio Herrera

This flexibility in his movements caused several tactical problems for his opponents at the time, both psychologically and mentally; what would Di Stéfano do? Dictate the game from deep? Or open up space for the runs of Zárraga or fall back to the other striker? Will he break through on the wing or run at us from deep? Is he working the back post or the top of the penalty area after wing attacks or is he playing as a safeguard, at the same time opening space but also supporting attacks further away from the penalty area?

This unpredictability, in conjunction with his game intelligence and his individual skills, made for an extraordinary clout in the penalty area, where he also combined many different aspects. The space interpretive deep and diagonal sprints from Thomas Müller, the killer instinct for rebounds, bad passes, or small holes in the penalty area of Gerd Müller, a sudden presence after previously disappearing from the game a la Karim Benzema or sometimes a Messi-esque occupation of the penalty area zones, all in one man – have fun defending a player like that.

23 minutes: A cross from Paco Gento into the left side of the box. Di Stéfano is in the penalty area but surrounded by two players, one of the defenders clears it. But at the top of the 18 yard box del Sol gets the ball. He plays it square to Canário who passes it from the right with the outside of his boot. Goalkeeper Egon Loy can not hold the ball and Di Stéfano is in the right spot! Like a gazelle, he jumps in front of defender Friedel Lutz and kicks up a cloud of dust, Hans-Walter Eigenbrodt can not prevent the goal. 2-1 to Real Madrid and a classic goal by Alfredo Di Stéfano – ice cold and with the right nose for goal.

216 goals in 286 games from ages 27-38, at that time the highest level (his time at Real Madrid), all while playing like a box-to-box eight, speaks for itself.

And along the way he also helped out defensively:

27 minutes: a bad pass by Luis del Sol, Frankfurt counters. Di Stéfano is the right center forward near the ball, but can not intervene, so he immediately rushes back. Frankfurt switch the game from the middle to the left wing with an expansive pass. Marquitos must move out of his half-back position to press right winger, Erich Meier. The quickly retreating Di Stéfano meanwhile occupies Marquitos’ vacated position. Thus, Marquitos is protected and can provoke Meier into losing the ball. Frankfurt receives the ball again after a loose ball in midfield and beats him well behind the resulting hole, but there is no one there. Santa Maria and the Frankfurt striker run together behind the ball as it goes out of play.

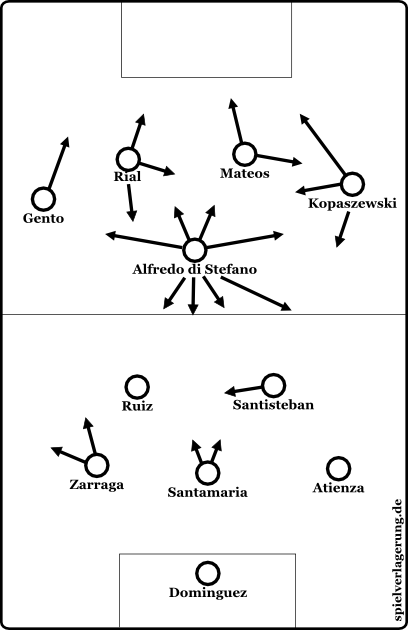

Real Madrid 1959

In the Champion Clubs’ Cup final against Benfica in 1962, at the tender age of 36, Di Stéfano sprinted the entire length of the field from his center forward position and intercepted a cross at the back post, playing as a sweeper in his own half. Generally, Di Stéfano displayed his outstanding game intelligence and athleticism off the ball. When playing behind the strikers he sought supporting positions in the (then, of course, unstructured) pressing, put the opponent under pressure very dynamically with his physical presence, blocked passes in the middle of his large Aktionradius and remained intelligently ball-oriented.

In defensive transitions he tracked back with extreme presence and covered a lot of ground. He deftly moved between the rare short breaks, where he didn’t help, to very aggressively pressing his opponent, to a rather space-oriented backwards pressing to support his teammate and simply positioning himself deeper to maintain compactness and security. The stamina and athleticism he displayed was ahead of his time. Di Stefano was outstanding in interpreting the potential dynamics and underlying structures, anticipating intercepting neither the opponent’s first or second pass, but – as in the Benfica scene – the last pass near the penalty area.

The stamina and athleticism he showed here was ahead of his time. Di Stéfano was outstanding in interpreting the potential dynamics and the underlying structures, was anticipatory and did not intercept the first or second pass from the enemy, but – as in the example against Benfica – often only in space near the penalty area. He even brought a great robustness and dynamism when tackling that would have served to honor even a defensively strong full-back.

But Don Alfredo was not only tactically outstanding on a group and team level; he also happened to play football.

Tactical individuality and playful features

The corrective ball control has already been mentioned; but in addition to the many small changes in his field of view, Di Stéfano could draw an additional strength from his movement dynamics and also the direction of his runs: he delayed gaining space via his runs. He extended his path through almost a zigzag-like pattern and provoked the opponent into an action, but could then react immediately. Putting either a tight hook in the zigzag pattern and running around his opponent, who then had a very uncomfortable position from which to track, or breaking out of the pattern and starting a sprint forwards. Together with his great ball and combination play he emerged from dangerous shorthanded situations and opened spaces very efficiently.

Generally, Di Stéfano used the many decision-making problems of his opponent to put himself in a better situation; not only positionally, but psychologically. A standard Di Stefano trick was to incorrectly open and position himself to the opponent. This means that he actually stood next to an opponent and did not (immediately) run into the open space, but stopped the ball in the direction of the enemy and with his body twisted away from him. The enemy would then take the bait, of course, and Di Stéfano would immediately correct his supposedly incorrect position, pull the ball towards the open space and only then begin his sprint.

The effectiveness of this delay: via this opening, to attract an opponent and only then start coming into the space, allowed Di Stéfano to control the tackling behavior of his opponent. If Di Stéfano immediately ran up top, then his opponent would normally have to run after him from a side-on position before he could go diagonally to the ball (which is more effective), and thus blocks an entire direction; Di Stéfano could then not go to the left or right side, at least not in one motion. By baiting the opponent forward his path is not diagonal to Di Stéfano, but behind him. Di Stéfano now has many options in all directions, the opponent must attack him from behind, where Di Stéfano can block his path and/or extend his run or simply draw a foul.

Real Madrid 1960

Often he avoided this “trick” and duplication; the deeper standing player wouldn’t move forward because the distance to Di Stéfano was still great. Di Stéfano played off the opponent, turning forward, and could therefore go for a relatively simple 1-v-1 two consecutive times (once by the movement of the opponent, the other through his speed advantage), rather than in a difficult 2-v-1, in which he would be missing a part of his movement options. But of course he decided, based on the distance to the second opponent, which option was best.

In general, Di Stefano presented many such allegedly faulty and risky positions, which caused tactical and psychological problems for opponents: Leave position? Press? Wait and see?

36 minutes: Now the Madridistas conjure the white ballet dance! José María Zárraga kicks from the right wing in his own half a precise diagonal ball to the left wing, at about the level of the center line. Paco Gento stops the ball first going forward, Richard Kress sprints diagonally backwards from the half position, but Gento sees him and stops the ball backwards. He then tries a through ball via a rabona, twisting the left foot behind his right standing leg, and passes to Di Stéfano. This lets him drop off the nearly half-height ball right back to the left while looking to the right. José María Vidal receives the ball, goes with him briefly to the right and plays across a short pass to del Sol. By an outside of the boot pass he conveys it directly diagonally backwards outside his field of view, where he – perfectly timed – has moved towards Di Stéfano. He starts moving from the center toward the right offensive half-space, allowing the ball to rebound from his right foot to his left in his run against the opponent, thereby changing his pace. He then immediately prances with both feet on his run over the ball. The defender tries to cut him off but is denied and Di Stefano plays the ball backwards. Afterwards there is a back-pass and renewed search for a better buildup – but: gorgeous circulation! Somewhere in the stands a boy named Alex cries with joy.

If the opponent chose the active variant, Di Stéfano often used drag-backs, letting the opponents chase the ball and turning around his own axis into the resulting open space or made tight hooks to swirl around the opponent. These very tight hooks and pulling movements with the ball were then often followed by long-range actions: passes into open spaces, fast sprints and dribbles, and switched balls. In addition, Di Stéfano almost perfectly held the distance to the opponent, where his drags and hooks worked tremendously well against the approaching opponents.

If, however, the opponent remained passive, Di Stéfano used the space. Besides his previously mentioned ability to control the game’s rhythm and his demanding, playmaking passing game, Di Stéfano was also a very strong dribbler and a very dynamic player, but was in some ways surprisingly unaesthetic and inelegant. So he sought, if necessary, the direct fast action when he was pressed or when the situation called for the fastest possible action.

For example, he would execute a step over forwards, a direct twist, but no subsequent interim step, yet pull off a difficult pass from an unpleasant position in the resulting dynamics. Even when receiving the ball on the right, he often played direct, inelegant passes with the left directly forward, letting the physical position affect the pass unaesthetically; But Di Stefano’s technique allowed for a high success rate (in my opinion) in these scruffy actions.

Real Madrid 1962

Alternatively, Di Stéfano moved into the free space if no direct action was needed. In his dribbling, Di Stéfano used a number of different aspects: for example, the Gambetta, which was explained in the in-depth analysis of his compatriot Lionel Messi. When Gambetta body deceptions are used, especially upper body movements, the goal is to change the balance and the position of the enemy and to respond to these reactions by taking advantage of the resulting space. Di Stéfano was not as fine as Messi or Diego Maradona; his movements with the upper body were far reaching, but not quite as precise and in his senior years – which comes from the sparse video material available – lacked some of the acceleration of the two magic gnomes. In a way, he had almost funny-looking upper body movements, where he went along with his legs and waited for the reaction of the opponent; a kind of hectic “Fidgety Gambetta” you might say.

72 minutes: What a game! A minute ago, Ferenc Puskas made it 6:1 with his fourth goal, right after Erwin Stein makes it 6:2. So now it’s back on offense, this time for Madrid. The three star strikers of Real are at the kick-off point, Gento right next to it. Puskas plays to del Sol, who passes to Di Stéfano. Di Stéfano is attacked, plays the ball square to Gento. Gento on the ball, he rises, twists back and plays to del Sol, who can again bounce it to Di Stéfano, who has moved well forward. Immediately Di Stéfano moves forward, Frankfurt’s defense is much too deep and lacks compactness. Puskas gives depth, but he actually does only one thing: he watches as Di Stéfano dashes forward with the ball at his feet, with a lot of space pushes into the penalty area and skillfully strikes the ball into the right corner. From the kick-off point with a few passes and a di Stéfano run it’s 7:2 for Real Madrid in a crazy game!

Therefore, Di Stéfano probably took his few fine movements, his larger body and leg length (in relation to the opponents), and expanded his arsenal at dribbling. He had an almost clumsy step-over, but from the outside to the inside rather than the inside to the outside that he would string together several times in his run. He protected the ball so that he could move it away from the opponent with the outside of his boot and dodge attacks. But sometimes he did not go to the outside via these inverse stepovers, but inward or without a stepover; usually with tight hooks diagonally past the enemy, barely losing speed, and thus it seemed to the enemy as if he was loaded by a shot – even though it was “only” the abrupt change of direction in the run.

Furthermore, Di Stéfano moved up not only from the side of the ball, but also vertically. If the the opponent remained standing or guessed wrong, Di Stéfano went past him. If the opponent responded better or cut him off, then Di Stéfano presented a step-over motion but brought the ball back, turned around or continued his run sideways. In addition, he switched feet while carrying the ball and used “impact-croquetas.”. The “croqueta” is the change of foot (usually in slow running), where the ball rebounds from one foot to the other, and the opponent is dodged. Di Stéfano does this also, but in his version he played with the ball moving from his front foot to his back foot and then knocked it directly forward. Opponents then hesitated, while Di Stéfano just kept running normally. Di Stéfano also did this when he stopped the ball with his sole and retreated, then curved around the opponent or simply changed direction.

But, Di Stéfano did not always infiltrate the open space given to him; which is another difference between him and Messi and Maradona, who have an instinctive urge to do so. Di Stéfano did not always sprint into a gap or at the opponent, but often played – even for rhythm reasons – with restraint. In this case, the already mentioned good distance holding of the opponent was combined with the rhythm delays; as Di Stéfano faked actions, for example, raising the foot as if to pass, pointing to a certain direction and stopping the opponent leaving position to press him very early on. Then he could wait a moment longer before he decided on an action or a run. Sometimes he even held his foot up, suggesting several actions, or simply paused and took up further precious seconds.

In addition to these dribbling skills, Di Stéfano was spectacular in the passing game: single no-look passes, difficult layoffs, many backheel passes outside his field of view in all directions or passing forward with the instep behind his standing leg. He could even handle difficult high balls or pass with his heels. Furthermore, he could play inch-perfect layoff passes past the opponent or dynamic lobs, often with the inner part of the metatarsal bone rather than from bottom to top with the toes, in his repertoire; as well as many outside of the foot passes, even over long distances, despite being a two-footed player. However, the outside of the boot passes were not the spectacle, but how were they were chosen in each situation, which spin was needed, how fast the ball was played and where the ball was played.

“I was right footed, so my father did not let me play until I could play with my left foot” – Alfredo Di Stéfano.

Conclusion: Ballet dancer, conductor of the orchestra, sniper in the penalty area

This analysis is ultimately about creating a tribute, in the shadow of the World Cup, to one of the greatest players of all time, who unfortunately passed away recently. In keeping with the World Cup, he is perhaps the greatest player who never won a world championship; but he was not only the face of the European Cup and Real Madrid, but modern football.

Real Madrid 1964

To date, Di Stefano is an ideal and will be forever. He is the total footballer, the benchmark of completeness, and almost every possible definition of this vague term. He could briefly hold all outfield positions, stand out in every position, had an impressive tactical intelligence and tremendous individual skills. Even his heading ability was impressively pronounced. He could stop balls in free space if they were available, pass the ball accurately or generate great force in the shot with his head. In addition, he was bigger than life itself as a personality; as the English say.

Off the field he was always seen as an icon at Real, fetched some Cup wins as a coach, including the Cup Winners’ Cup in 1980 and three championships, among other things, with Valencia in 1971, where he was considered one of the foremost pioneers of pressing. On the field, his charisma was impressive. Di Stéfano had an impressive mix of dynamism and a certain inertia, which is really best described with my favorite word “languidness”; a certain flair that lacked aesthetics, but had its own elegance, evidenced by the many wait-and see aspects in his game. In his litheness he resembled Zinedine Zidane, yet, had significantly more presence, more strategy in his facility, and completeness in his implementation.

To this end, his outstanding rhythm control and strategic decision-making was coupled with his presence all over the field. To underline his completeness: only Di Stéfano combines all three of my own personally defined talent types . He was incredibly smart, incredibly talented and incredibly active, which made him unbelievable. A “leader of men”, a commander on the field, he gave his teammates orders with his body language, gestures and facial expressions, his words, but also his passes, his decisions and runs.

85 minutes: The tireless Di Stéfano lets the ball the goalkeeper thrown from his own penalty area. The Frankfurt striker, Stein, presses backwards on him, but Di Stéfano anticipates well and plays diagonally forward, del Sol rebounding the ball back. The half-left Zárraga lays the ball square back to Di Stéfano, who is pressed again, but able to lob the ball into the path of Vidal. He heads it back to Zárraga who moves forward with the ball. But stop, what is Di Stefano doing there? He offered himself previously for Vidal, then ran around Zárraga and into Zárraga’s path. Di Stéfano indicates to Zárraga to go away and takes away the ball! Obviously, the real star, in the closing stages when the score was 7:3, was not fast enough. He immediately moved the ball to the left, forcing Gento forward with a pass into his path. Gento passed to Puskas, but Frankfurt’s Eigenbrodt cleared the ball into touch.

Of course, this can lead to problems. It would not surprise me, for example, if the well-known dispute between the great Didi and the great Di Stéfano was that their respective playful greatness had a negative impact on the group’s tactical synergies, which in turn were responsible for psychological problems and in-fighting. Just imagine the reactions of the two, if Didi were to shoo the retreating Di Stéfano away, while Di Stefano ignored him and took the ball away from him. Nevertheless, Di Stéfano was by no means a General or an egoist, but was looking for the best option for the team in his own way; who could arrange themselves, and benefit from it. Di Stefanos dribbling, his ball distribution, his seeking of one-two passes and his demanding passing game were always positive with respect to the big picture.

The best example is Ferenc Puskás. These “major” problems with Di Stéfano were predicted, but the opposite was true. Puskás facilitated Di Stéfano’s offensive work, played surprisingly goal-oriented in his combination movements, brought depth to the game and acted as an enormously powerful passing option up front, who could play technically advanced layoffs, dangerous shots from overloads, or switch the ball to the strong side. In many cases, Madrid then played in a clearer 3-2-4-1/3-2-2-3 formation, which helped Puskás – in those years rather round on the edges, not only with a big belly, but also with thick knees and ankles – extend his career. The contradiction of Di Stefano’s putative egoism with his success and the reverence of almost all of his teammates shines light on these two personalities – Puskás and Didi – making their dispute relatively easy to dismiss.

Another difficult question to answer: How did Di Stefano become who he was? Was it the positive influence of Adolfo Pedernera, with whom he once played at River Plate? Was it the result of his talent and his character, in conjunction with contextual factors of the opponent and trainer requirements, which made him this incomparable player? Were there more players like Di Stéfano and Pedernera back then, while today it’s simply not possible to play like that? After all, Valentino Mazzola and years later, Johan Cruijff are still similar players.

What is important is the consideration of the development of Di Stefano’s player type throughout his career. At La Maquina, according to the reports and research results at least, he acted goal-oriented in his movements, and generally focused on the last third of the field, but was not particularly defensive or quite as involved in the deeper buildup game as he was years later. His prime has also been lost: it is said that at Millonarios in Colombia he was even more powerful, dynamic, and had a greater presence than later at Real. Video sources to substantiate this, however, are missing.

But they are unnecessary. Alfredo Di Stéfano was great. He was an outstanding football player who should serve as a model for many players today: disciplined, ambitious, individually outstanding, but also a player who made the collective stronger. Di Stéfano was not only the first “total” football player, but is to this day the total soccer player par excellence.

“Alfredo Di Stéfano had a peak Goal Impact of 189. An incredible value at that time. Still the seventh highest peak Goal Impact of All Time “. – Jörg Seidel of Goal Impact, the Bobby Fischer of football and the Goal Impact metric (only one player from the 90s had a higher number than Di Stéfano, his teammate Francisco Gento).

Worth Reading: A short story about the bizarreness of Di Stefano’s move to Real Madrid.

Must-see: a documentary about Di Stéfano.

Written by RM

Translated by @rafamufc

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

getterJAM September 30, 2015 um 7:55 pm

Thank you for the comprehensive analysis of Di Stefano. I have studied his game for decades and made this clip of Don Alfredo.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YuqEVVZGk1U

Emmanuel September 8, 2014 um 12:02 am

This is one of the best football articles I have ever read. Those who watched him revered Di Stefano. I didn’t,but I’ve always wanted to understand his genius. Now I do. It will be almost impossible to see a player of his nature in the modern game. Thank you for the article.