Atlético Madrid under Diego Simeone in 2014

Atlético Madrid is Europe’s surprise team – and has been for about two and a half years.

On December 23, 2011, Diego Simeone took over the ailing rojiblancos at a time when they were almost in a relegation battle; for Atlético fans it has likely felt like Christmas for the past few years. They had taken 19 points from 16 games before Simeone took over in 2011/12 and they took 37 points from their next 22 games.

He has also taken them to the Europa League and finished fifth. In 2012/13 they finished “only” nine points behind Real Madrid in third place and defeated their city rivals in the final of the Copa del Rey. This year their fairy tale story could conclude with a potential league double and a Champions League trophy. This article will focus on the tactics that have brought them to their current position.

Atlético and the modern 4-4-2

The 4-4-2 hasn’t really gone out of fashion in recent years, but it has been the recipient of repeated criticism. It’s inflexible on offense, the Zehnerraum(ten space) is abandoned, it is easy to isolate on the wings, and a “beautiful game” is thus hardly even possible; for the Englishmen the 4-4-2 is regarded almost as a metaphor for the many failures of the national team in recent years. As a defensive formation, however, the standard 4-4-2 is still used by the majority of teams.

Atlético line up in the match against Malaga with a unique and very classic 4-4-2, which they very rarely use.

The rojiblanco, on the other hand, are one of the few teams that use the 4-4-2 on both offense and defense. And, in contrast to the English or the classical implementation, it works. What sets apart their implementation is that they neutralize the inherent disadvantages of the 4-4-2 with small but important adjustments.

What is outstanding from a strategic/tactical point of view is the fundamental influence on the center, especially in the ten and eight spaces, which are usually seen as the most important strategic areas in football. In a basic, static 4-4-2, these spaces are abandoned and Atletico keeps with the tradition of abandoning the ten space; however, they play more of a 4-2-2-2 where the wingers increasingly move into and align their position with the half spaces.

As a result, Atletico can use Koke and Arda Turan as indented wingers, with a center forward dropping deep, or occasionally moving up a six to fill the hole in the middle . They do this with not just one of these players, but sometimes even three or four, in order to briefly create a narrowness for quick combination play with attempts to break through and balance movements on the wings.

In some ways, this approach is reminiscent of a theoretical dispute in chess strategy. Actually, all grandmasters and chess theorists share the view that, in chess, it is crucial to control the middle of the board. On the precise nature of this control, however, there are split views.

Siegbert Tarrasch spoke, for example, of the simple occupation of the center as an opportunity for central dominance, while Aron Nimzowitsch placed an emphasis on Figurenwirkung, controlling the center of the board without necessarily physically having pieces there, i.e. using the unique powers of the chess pieces to control the central squares from a distance. This view was later called the “hypermodern school“. One might draw a similar comparison to football, which is obviously a dynamic sport and has more “natural” zones (as you will see in the coming weeks in some new articles about the half-spaces); which makes this dominance by Figurenwirkungeven more interesting.

Atlético has demonstrated this well this season. Using the winger as a half-space player they have the option to pass from one half-space to the other to force the opponent into a more complex move without having to pass along the wings. Arda and Koke are also adept at using their dribbling skills to combine and try to open spaces, or position themselves for through balls in the space between the lines.

The opposition has many problems with this, because it can be difficult to establish access. Many teams defend in a 4-4-2 or 4-1-4-1; in the former, either the six or the indented winger is freed by this movement. If the opponent reacts with a consistent man-marking of the wings, then the lateral zones will be open to the full-backs, Juan Francisco and the outstanding Luis Filipe. In the 4-1-4-1, the passing obviously works better and is easier, but the high pressing resistance of Arda and Koke, in conjunction with their passing and dribbling skills, ensures problems in the open half-spaces; even if some combination of the opposition full-back, near six, or winger try to attack them.

In many cases, Atlético varies their offensive style of play. In some games there is a greater focus on the wings or the two wingers play very asymmetrically, where one stays wider and they move inside in different zones. Koke, for example, likes to move in the direction of the Achterraum (eight space) and act a little deeper, where he can have a more control over the rhythm of the game. Arda, on the other hand, likes to sit higher and be more goal oriented.

The squad and the distribution of their roles is almost ideal. Diego Costa and David Villa, or alternatively Raul Garcia, can fall back as wall players for fast combination layoffs, and are options for long high balls which they can then hold and layoff to the indenting wingers. In addition, they also repeatedly move to the wing when near the ball, to receive long balls (Diego Costa) or act as a safeguard and space opener for the winger (David Villa).

This naturally suits the fullbacks. Juan Francisco is a technically strong player, who even played as a ten when he was younger, but acts a bit too linear for this position. He can break vertically on the right flank or play diagonal passes to the center. On the left, however, Filipe Luis is probably one of the three to five best left-backs in the world and with his tremendous dribbling skills, ability to create combinations, and his athleticism, can play as either a classic full-back or a diagonal full-back. He often gets into and beyond the channel between the opposing fullback and center back and into the penalty area or plays into the middle third via forward runs as a diagonal full-back into the half-space, where Arda or another winger (or even center forward) can then briefly provide width.

Considering where and how they play their personnel, their collective positioning, and their ability to find space, Atlético is extremely difficult to defend. Players like Koke, Filipe Luis, and Arda Turan, but also the two sixes, are examples of the lasting individual strength of the team. It is well known what Diego Costa possesses; an incomprehensible acceleration, which often betrays his speed, the ability to cause the opposing central defenders physical and mental problems, an enormous brawn, and a high skill in motion coupled with a great workrate.

This composition of polyvalent and complete players in the offensive four also allows them flexibility in choosing their attacking moves.

Variability for penetration

The flanks are often rejected as a tactical means by many of us here at Spielverlagerung (and rightly so). It should be noted, however, that Atlético has crossed very well and very intelligently in many of their games. They have a lot of movement in the middle, possess excellent Dynamik on the wings and can thus create problems when passing laterally as well as into the box. On the sides they have good crossers and, with Raul Garcia and Diego Costa, they have two of the strongest headers in the world.

Furthermore, they put these crosses into good zones; diagonally to the back edge of the box, diagonally from deeper zones in behind the defense (as in the Chelsea goal), or even sharp, low crosses to meet intelligent forward runs into the penalty area.

There is also a nearly perfect protection and occupation of the penalty area, thereby avoiding counter attacks and utilizing long shots or counter pressing as play-making elements. Long-range shots, counter pressing, and the risky combinations that are made possible by using counter pressing as a safeguard, also belong to their standard repertoire.

Costa advances into the right half-space in anticipation of the long ball. Raul Garcia and David Villa start a cruising motion to dynamically get to a flick-on. Gabi moves up for potential layoffs.

What is most spectacular, however, (for me personally) are the lightning-fast, short passing combinations in confined spaces, from where they seek a shift with the wing or half-space breakthrough or a through ball. It is interesting how rehearsed this is. Not just the aspects of group and team tactics, but also the individual actions.

In many cases, a very fast pass will come out of the six space to one of the indenting wingers. He does not, however, stop the ball, but leaves it for the center forward, who has already positioned himself to receive the pass. As a result, the center-forward can use the momentum of the pass to quickly drop directly into the middle, while the winger moves on.

These dummied passes cause confusion for the enemy. They can lead to poor shifting and transferring (players often don’t anticipate the situation and “shutdown” or stop moving) and are often used to integrate the runs of the full-backs. Whether the through ball is interrupted, and a back-pass or individual breakthrough attempt is made depends on the situation – which in turn means variability.

Atlético Madrid also uses these combinations in possession – even in forced possession against very deep, passive opponents – as a “counter-team”. They attack quickly and create chaos and disorganization to find a rapid breakthrough. Against very compact and defensive teams it will be necessary to simply get a number of chances and seek a quick shot to generate a constant and simple goal threat.

This is not only psychologically and tactically a good idea (if it is applied flexibly), but also strategically well thought out. Atlético can be difficult to handle on the counter because they are really outstanding in their defensive Umschaltspiel (transitions) as well as in their protective alignment in possession and rarely allow themselves to be countered.

An interesting side effect: Due to the high number of shots faced, the opponent often has to build out from goal-kicks against the Atlético defense. They then fall right into their pressing vortex or their shifting becomes textbook – Frank Wormuth would likely fall into ecstasy with their doubling up on the edges- and they hardly have a chance to play out. Meanwhile, Atlético can prepare their dangerous counter attacks for after they win the ball. And you can be sure that they will fight for the ball anytime and anywhere on the pitch. Diego Simeone will take care of that.

The man who tinkers with the Staffelungen (staggerings)

There is hardly any team that adapts to its opponents by changing the distances within their formation and their tactical operations quite like Atletico Madrid does. They do, however, have a default orientation that serves as the foundation for these adjustments.

Atletico Madrid often play in a 4-4-2 with a deep midfield press. The two strikers work up to the central midfield and the midfield chain is narrower than the defensive line. The wingers set up in the midfield rather than on the wings in order to occupy the half-spaces and provide horizontal compactness. Because of this and the movement of the two strikers, the opponent is lured to the wings, where they are then very aggressively pressed.

The full-backs in the wider back four man-mark their opposing wingers, press them when they receive the ball, and adjust to them directly. The narrow midfield chain and the dynamic shifting of their other teammates forces the opponent to pass to the sidelines, giving Atlético almost constant control over the center of the pitch.

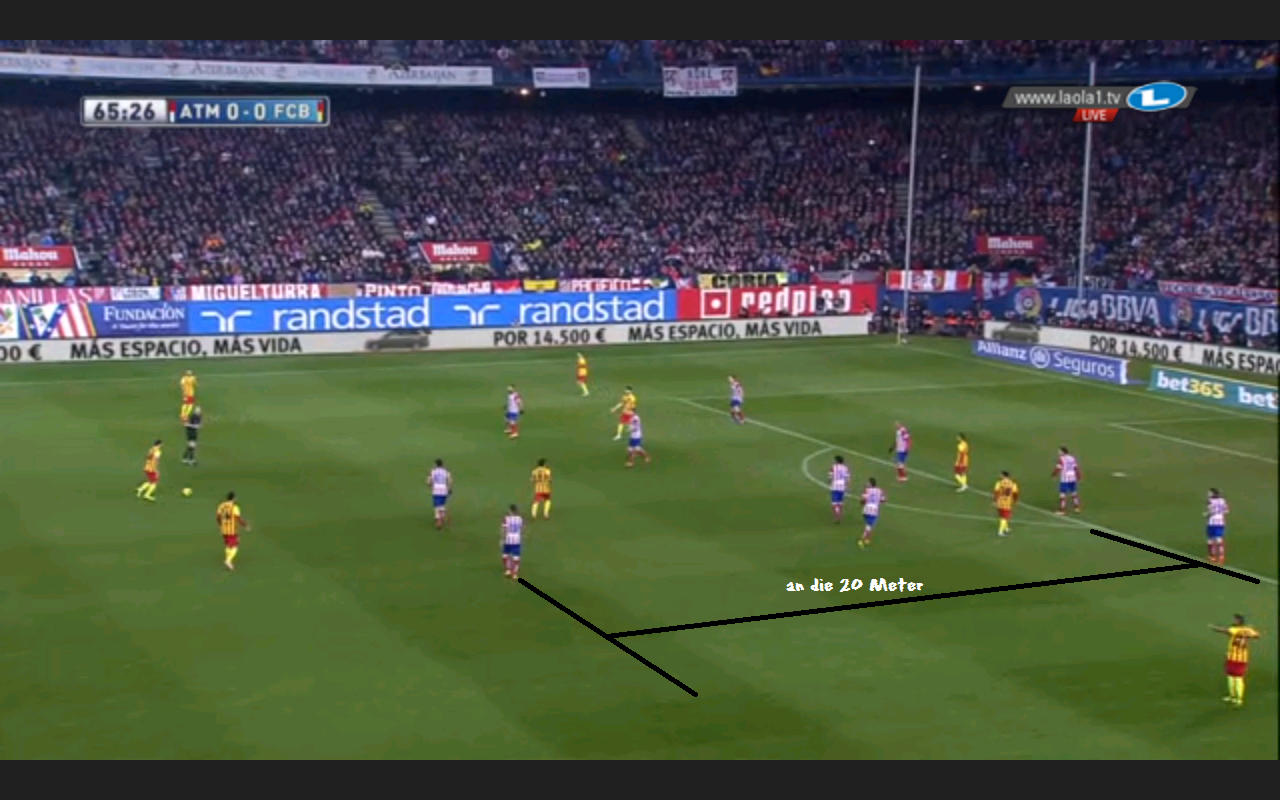

Chelsea tried to play with wide wingers (Azpilicueta on the right) and a very mobile ten, but only had one successful moment. Barcelona, however, ran right into the compact center, but could never break or keep the ball in between the lines and were always pushed back or to the wing, where they were ultimately isolated.

From a tactical point of view it is particularly interesting for me to see the movement of the two sixes during the opponent’s ball circulation. The near six (closest to the ball) moves slightly forward to support his side of the pitch. He can then situationally press the opponent’s six or protect the wing and block the horizontal passing lanes. The far six (furthest from the ball), however, can fall back and play closer to the center backs, forming an asymmetrical staggering of the formation.

The logic is simple, but brilliant: The far six plays as a situational midfield libero. I wrote about this in my analysis of FC Barcelona, where this style of play has been used very effectively.

Diagonal passes from the defensive half-space into the opposing offensive half-space were impossible. Vertical passes into the space between the lines were immediately harassed several times; the deeper far six pressed them from the side, the higher near six reoriented and pressed backward, the near winger pressed from the other side and one of the central defenders moved forward. If the second, far six stood higher – a la Barcelona’s infamous third man run – it would enable direct layoffs for vertical passes into the open space between the lines. Thus, 4-3-2-1 and 4-1-3-2 formations emerged, which usually just looked like a 4-4-2 because of their sheer compactness, in which only a six and a striker stood slightly offset from their neighbors.

This was not played in a defensive press because the intermediate line space was practically non-existent anyway. Atlético clenched so tight that a pass into the intermediate line space was impossible. There was a clear 4-4-2 and the horizontal lines in the bands seemed to almost be drawn straight across the pitch.

This shows that these slight positional adjustments are more complex for the opponent to handle and there are certain situations where specific Staffelungen (staggerings) are extremely effective – which is backed up by Atletico’s goals against statistic. In the swinging midfield Libero, for example, it is the lateral shifting to prevent the opponent making risky diagonal passes. The rojiblanco six blocks the entire other half of the field with his cover shadow and thus supports the horizontal compactness of the far player, allowing for more extreme indenting.

In other matches the two chains play similarly wide but the two sixes and two strikers do not generate asymmetric or completely different staggerings. Against Chelsea they even switched to a 4-1-4-1 to maintain the lead and also vary their height and ability to press. Atletico doesn’t always attract their opponent to the wing in order to isolate them. Sometimes they flip the script and push their opponents into their own open ten space in order to tear them to pieces.

The two wide center forwards position themselves between the full-backs and center backs of the opponent or even behind the center-backs, and then use arcing runs to block any passing options to the side. Because of these runs, the opponent must play into the center of their defense. The strikers can then work backwards, the wingers can press from the sides, and the sixes can move up to attack the player who receives the ball. Six against two, even at the professional level, will result in a slightly uncomfortable situation.

And, in a way, this also corresponds to the “ultra-modern school” of chess, where the lack of central occupation is used as bait to set a pressing trap. They also try to prevent the opponent from turning once they receive the ball, to the point where they can’t even get relief from long balls. Sometimes the strikers move further forward to press the goalkeeper and encourage these long balls.

Thus, Atlético can press in a 4-4-2, 4-2-2-2, 4-4-2-0, 4-4-1-1 and an extremely compact 4-1-3-2, by varying the distances, the pressing height, and their tasks. From a deep defensive press with a lot of passivity and passing along the wings to a high attacking press with tremendous aggression and passing in the middle. In general it can be said that they work on a lot of Herausrücken (leaving position to press), with a lot of athleticism and aggressiveness. These moves are then protected by collective balance movements, which creates a great Dynamik.

These tweaks to the tactical operations and situation-specific adjustments to the staggerings are not only present when they are out of possession but also in building their attacks.

Staggering shifts in the buildup game

As previously mentioned, there are many ways to have the wide players indent and flood the middle and final third of the field. However, it’s also possible to do so in the first third where the asymmetry is even easier to see. Occasionally, the near winger moves backwards diagonally and opens space for the full-back. This in turn opens space for himself while the far winger moves into the ten space. Atletico handle this a bit differently.

Normally it is Koke, who constantly goes into the left defensive half space and creates a kind of 4-3-3, with Mario Suarez or Tiago and the captain Gabi, which occupies the two defensive half-spaces and the center. This creates, in extreme cases, a 2-3-3-2 with very high wingbacks, reminiscent of Southampton’s style of play, but with different types of players and movement patterns. There is often an element of asymmetry; Koke indents into the midfield, Arda Turan gets behind the opponent’s midfield, one of the sixes goes into a half-space and the other remains central.

Atlético in the match against Malaga in a situational 6-3-1 – Koke and the two sixes cover a lot of space, the other players move way up.

The group’s tidiness is also important, i.e. the precise positioning in the enemy’s channels. If either of the indented wingers receives the ball, they are often exactly between two midfielders. They can then quickly turn and know they have at least a few meters of space from the nearest opponent, which in turn facilitates the following pass. Arda and Koke also often swap sides specifically to play against the weaknesses of their opponents and create other synergies.

At times the two center forwards even play alongside the opposing central defenders to occupy them. They can support at any time on the wing and in the half-spaces and be able to launch forward from deep. Their own central defenders fan out intelligently. Courtois can assist them to play hard and the full-backs also move flexibly; they play extremely high or only slightly offset from the center-backs, depending on the situation.

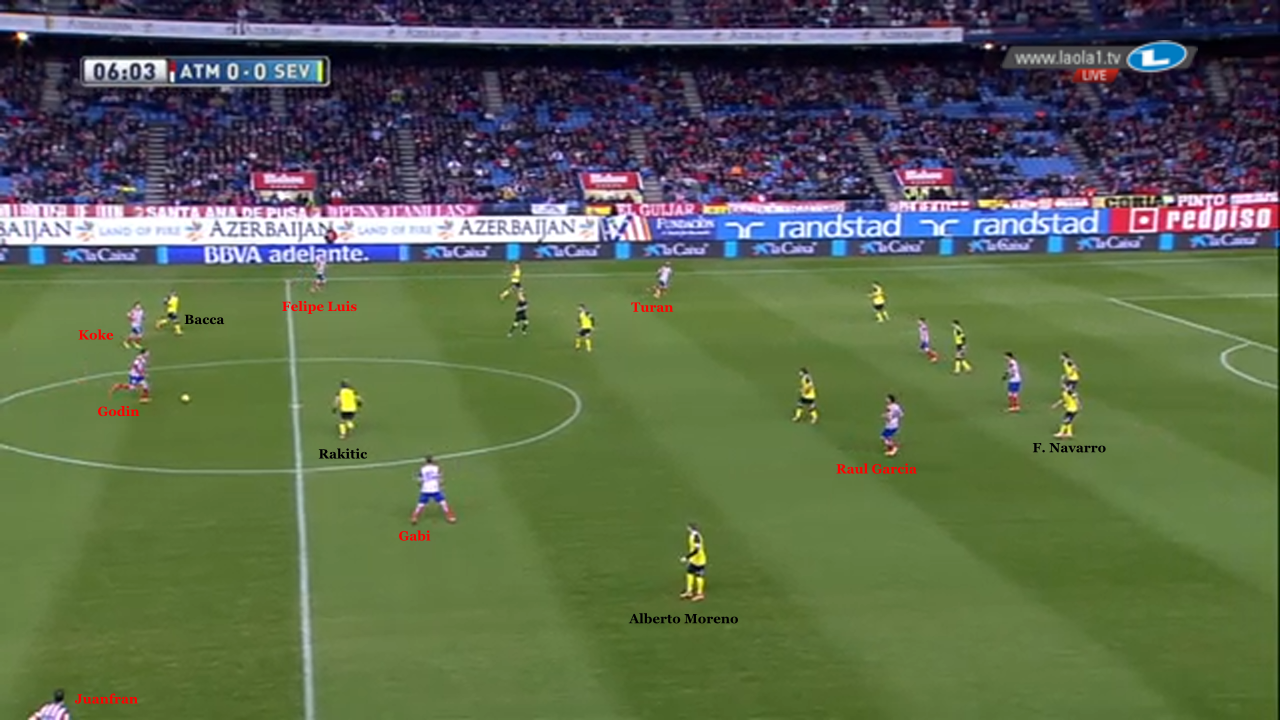

In the paragraph, “Atlético’s dominance,” in the analysis from the match between Sevilla and Atlético, my colleague TW also wrote about their attacking capabilities. They played well against the enemy’s movements via, among other things, Diego Costa falling back and Diego Godin moving up .

Godin played against the man marking of Sevilla FC with an aggressive move forward to the open space near Koke and Gabi. He lures Rakitic away from his opponent, Gabi, to the center. Alberto Moreno does not move in to take Gabi, because he is marking Juan Francisco. He then picks up speed to attack the space that has been freely drawn out by Raul Garcia. The close position of Navarro in the center against the two Atlético strikers is also striking.

This game is a good example of Koke acting as a six with Raul Garcia on the right and Arda Turan on the left. Thus, with simple changes (Koke to the center, replaced by either Garcia for more heading ability and presence, Diego for creativity, or Jose Sosa as a role player) they can add even more pressing resistance in the center and another imbalance in the buildup game.

Atlético is difficult to press in the first third and is by no means purely an Umschaltmannschaft (transition team), but they are just as good a team when the opposition has the ball as they are when they are in possession. Atlético is also excellent at altering their passing rhythm. They can move intelligently from fast, short combinations in confined spaces to a very expansive and direct style where they get the ball forward quickly with a few passes.

Furthermore, the short passing combinations help their Dynamik not only in their attacking play, but also in escaping from the opponent’s counter pressing. They then create better and more frequent opportunities for counter attacks after winning back the ball. What else is there to talk about? Ah, yes.

Set pieces

Ever since the Real victory against Bayern Munich, one must always note that there are teams that are sometimes quite dangerous from corners. And yes – I am no friend of set pieces or crosses. But, Atlético are a pleasant surprise, and should be commended for how they use these opportunities .

Many corners are sharp at the near post, where they move very well and at the same time still occupy the further trajectory of the ball. From there they can generate opportunities in the area or even deliberately redirect the threat. There are also some interesting tricks, such as against Porto, where they had nine men in front and one player provided protection. The opponent had to have ten men in a horizontal line of a few meters, which was ultimately responsible for the goal.

And against Porto, they achieved one more goal with a set piece trick: one Atlético player was behind the opposing wall, one stood next to it, three were far from the ball and opened space. while one stood very wide near the ball to open the channel. Three men were standing in the penalty area. The free kick was not what Porto expected, i.e. inward or played directly on goal, but a through ball into the hole that led to the goal.

In their set pieces, they have not only good crossers and bulls in the air (the central defender Garcia, Costa), but a smart head behind them, who cares about crossing movements, the right timing, good strategic zones, moves, and blockers. A crucial set piece in the CL final seems to be on the way …

Conclusion: Brilliant fulfillment of basic concepts and fine adjustments

Diego Simeone’s work at Atletico Madrid is truly outstanding – there is hardly a team as complete in fulfilling all the important strategic concepts at this level, perhaps only Dortmund under Juergen Klopp come close. The Umschaltspiel (transition play) in both directions is almost perfect. They practice an intense counter pressing, which is sometimes a bit expectant and forces the opposition into areas or zones where Atletico Madrid will have the advantage. They maintain outstanding formations as they come into possession (without keeping it for a long time) and work wonderfully without the ball; with perfect shifting and outstanding compactness. In their basic strategic orientation, they are creative, excellently connecting the modern and the antiquated. The formation of quick narrowness from really wide positions in the half-spaces and the quick combinations and flexibility of their pressing in the 4-4-2 are a highlight for every tactic gourmet.

Atlético’s 4-4-2 and Busquets in a stranglehold from the strikers, similar to the 4-4-2 (-0) at Bayern in the CL season under Heynckes.

However, Simeone alone is not responsible for this success. The athletic trainer, for example, must be praised beyond compare. It is amazing to see a team that plays with such intensity and with such a small squad remain consistent for two years without any major injuries, losses, or idle phases. And, of course, the players under Simeone deserve part of the success and cheers that he is receiving.

Filipe Luis, like Diego Costa, is absolutely world class. Thibaut Courtois is on his way to being one of the best goalkeepers in the world (if he isn’t already). Koke and Arda are imperious wingers. With Godin, Miranda and Gabi they have excellent system players. Raul Garcia, the aging David Villa, Diego, Tiago, Mario Suarez (on good days) and Juan Francisco are also international class. The advantage, of course, is that they are optimally involved and can therefore reach their potential.

At the same time it is also striking how smart the individual players are when they foul or are fouled, how quickly they support each other, and how adept they are in determining their position, as well as implementing the basic aspects of play. This ranges from a clean passing technique, to proper tackling, to claiming the ball in direct battle with the help of the hands. That should also be a credit to Diego Simeone.

Whether Simeone’s current blueprint can be applied to other clubs or they can maintain their current consistency in the coming years with this squad is a legitimate question. Nevertheless, one can be sure: in Madrid, the rojiblanco have done a lot of things right in the last two and a half years. It’s likely not by chance.

Thanks to laola1.tv for the footage!

Thanks to @rafamufc, who translated this piece for us!

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

julian January 9, 2015 um 5:33 am

brilliant manajer and leader in their team.they did a right thing with a right way.bravo simione!!!