Zonal Marking / Zonal Coverage

The two main types of defense used in soccer are man-marking and zonal marking. In this article we will explain the different types of zonal marking and their advantages and disadvantages.

Written by Rene Maric

Translated by @rafamufc

General information about Zonal Marking

Zonal marking was the first way defense was played. The original zonal marking had very little to do with the modern style because it lacked organization. One might call it chaos marking as everyone just sort of stood around and occasionally tried to win the ball.

Today, zonal marking is anything but chaotic. The advance of athleticism, game intelligence, and especially the professionalization of football, have led to the dying out of man-marking as players are individually stronger and better coordinated as a team. The gaps are now narrower and better covered, which mitigates the vulnerability of zonal marking between the horizontal and vertical lines.

In the late eighties, zone defense was extended further by Raumvernappung (squeezing space). In this style, the game was basically kept compact and the effective playing field compressed by the factors of time, space, and the offside rule. Arrigo Sacchi trained his players to use four reference points:

“Our players had four reference points: the ball, the space, the opponent and his own teammates. Every movement had to happen in relation to these reference points. Each player had to decide which of these reference points should determine his movements. “

– Arrigo Sacchi

In order to play zonal coverage, the team must consider these reference points when shifting and pressing to remain stable and prevent opening any holes.

That being said, it should be noted that playing a ball-oriented game is not zonal marking. The ball-oriented game refers to the adjustment of the player and his team to the movement of the ball. Which, in zonal marking, is usually applied much more when pressing and squeezing space.

Theoretically, it is possible to play zonal marking without being ball-oriented. It used to be quite common to not man-mark but mark space; yet not indent or constantly move in the direction of the ball at all.

It is also a mistake to believe that Sacchi’s four reference points only apply to squeezing space and pressing. They are generally used in the defensive game and the attacking game, which has the added benefit of the reference points providing reasons for playing the different types of zonal marking.

Zonal marking as a team

First, we will explain collective zonal marking, which is practiced by the entire team, and its variants.

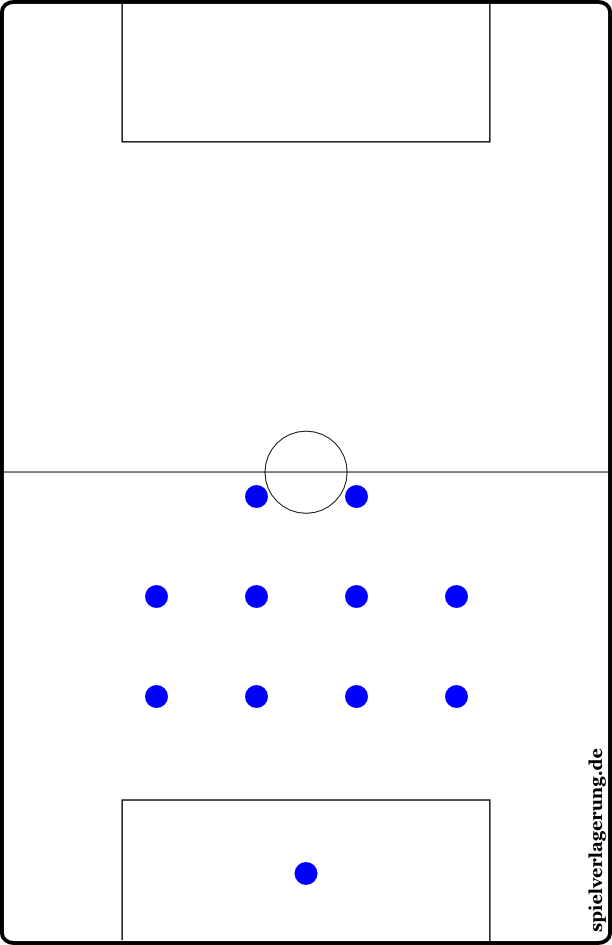

For easier understanding all of the scenes in this article will be based on a 4-4-2 formation in defense

Variant 1: Position-oriented zonal marking

In position-oriented zonal marking, the player’s reference point is his “teammates”. The team simply operates in a closed block. This ‘block’ is nothing but a formation, in which the respective positions are clearly defined and a player “covers” his own position. The term position marking could also be used.

Some examples include Lucien Favre’s Gladbach or Valeriy Lobanovskyi’s Dynamo Kyiv. At Gladbach, it is striking how effectively they move back and forth while often exerting little pressure on the opponents or the ball. Instead, they focus on thwarting attacks by controlling space. If the opposing team resorts to circulating the ball, Gladbach move so quickly and precisely that the supposedly “open” wings can’t be played.

At the same time, the vertical and horizontal compactness is preserved, so the opponent can hardly find space within the block. If they try to play into the narrow space, then the lines move toward each other (or only one line moves, depending on the game philosophy) and closes the space. Over time, this puts the opponent under pressure; resulting in winning the ball off bad passes or other technical errors.

The characteristics of position-oriented zonal marking are: clearly recognizable banks in defense and midfield, giving space to the opposition on the wings, and straight lines. However, the formation must not consist of equally wide chains or equal spacing between the various parts of the team. The goal is to keep the gaps and the space between the lines as small as possible.

In effect, this often looks somewhat passive because little pressure can be generated against an intelligent and cautious ball circulation. This season, Favre played it so that he pulled apart the space between the lines or intelligently moved the lines up to establish access for their pressing.

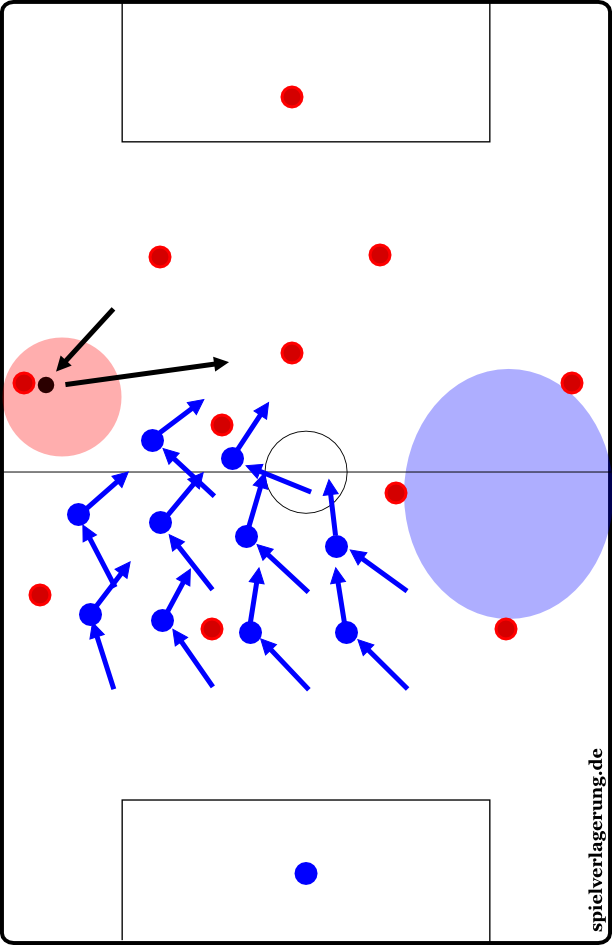

The opponent builds play on their right side, with what seems to be a 4-1-2-3 as a variation of the 4-3-3 with wide wingers. For illustrative reasons, we (blue team) are standing in an ultra-defensive formation.

The opponent plays to the right and the team moves as a group to that side of the pitch. The space that appeared to be open on the side for the winger is suddenly very tight and can not be safely played. The ball goes into the center and our (semi) left striker gets access and moves to press. The team follows his example and take the same running paths.

The opponent is approached slowly and step by step, which sometimes seems a bit laid-back. Despite the passivity and reduced access, however, the block remains stable and compact. Passes into the space between the lines are difficult and can be compressed by narrowing the team’s spacing.

Variant 2: Man-oriented zonal marking

In man-oriented zonal marking, you play with a basic formation in which the reference point is the “opponent.” From their respective base positions, the players orient themselves flexibly in the space they cover in order to maintain a certain distance to the opponent closest to them.

The contrast to man-marking is obvious. In man-marking, a player sticks very tight to an opponent, oftentimes even tracking just the one opponent. In zonal marking, a player must cover the space around his position, loosely moving his position to any nearby opponent and staying close to them.

In a way, it’s a compromise between position-oriented zonal marking and man-marking. The advantage over man-marking is fewer open holes. The advantage over position-oriented zonal marking is the increased access gained via the shorter distance to the opposition.

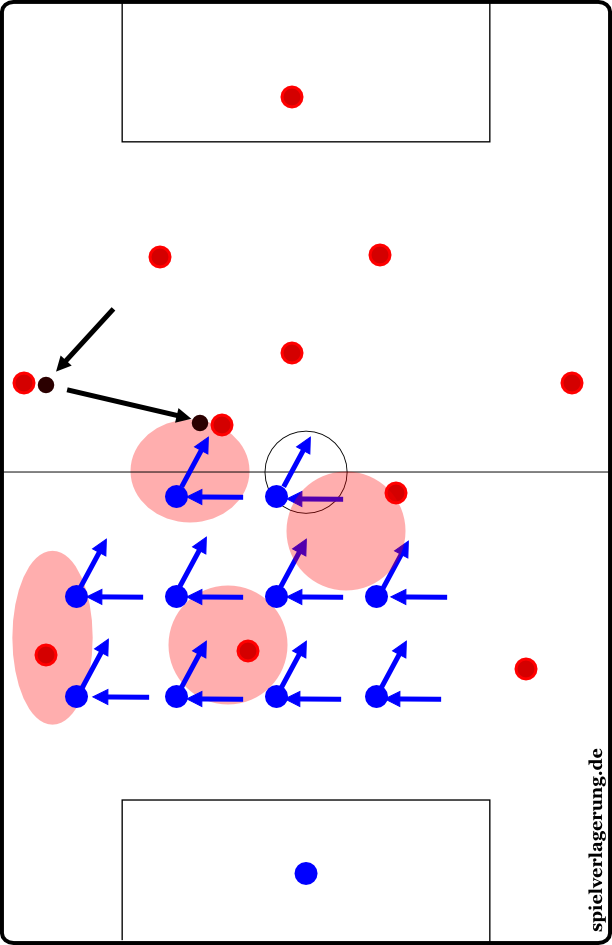

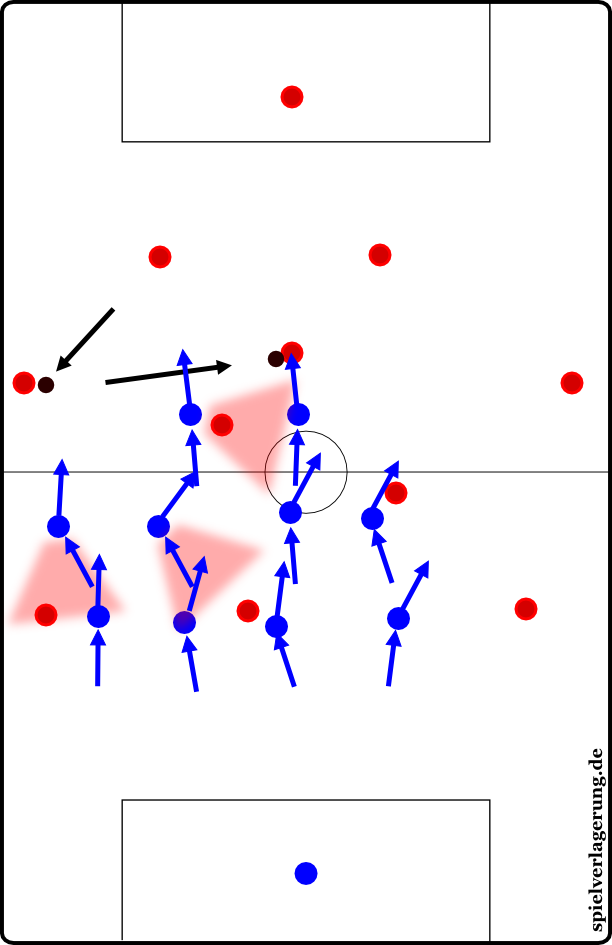

The opposing right-back receives the ball, so our team shifts to the left. It is striking that our sixes behave differently: one is based on the opponent’s right eight, one on their center forward. Our striker is also man-oriented, however not in the classic sense, but in space: he cuts off the passing lane for the opposing six, who is playing behind the other eight.

Alternatively, our other six could have oriented to the opposing left-half eight and the winger would have remained in space. So all the pass routes and options are blocked directly (by cover shadows or even situational man coverages) or indirectly (through access and narrowness).

The opposing full-back does not risk the line pass, but plays back. Our team therefore pushes out. The striker separates from the space around his opponent and begins to press. The far winger pushes out and, until the opposing center back handles the ball and continues playing, our winger is again near the opponent’s left-back. Our left six runs past the opposing right eight and is now “suddenly” oriented on the six of the opposing team.

In a way, one could say that man-oriented zonal marking, in contrast to position-oriented zonal marking, does not wait for access and pressing, but seeks it. The difference to man-marking is that the opponent will not be tracked or handed over to another teammate, but left to stand in space, and one can reorient themselves at any time. Furthermore, one does not focus on the opponent, but the action space and the access distance.

Variant 3: Space-oriented zonal marking

In this third variant, which is used much less frequently than man- and position-oriented zonal marking, the reference point is space. The team shifts toward the effective playing space “in the moment” and tries to occupy it.

On paper, one might think that sounds intelligent. The space would be overloaded and the opponent’s short pass combinations would be destroyed by a lot of pressure. In practice, however, this is not the case, if the opponents are even remotely smart. They can move into the many open spaces, particularly away from the ball, and destroy the opponent’s formation.

One example was the match between Valencia and Malaga, where Valencia wanted to restrict Malaga’s fluidity and situational narrowness with a space-oriented zonal marking, which failed completely.

In a sense, it was the lost twin of man-marking; in terms of idiocy. The pass goes as usual to the opposing right-back and the entire team is oriented on the new space.

They have no access, the pass goes into the middle, and they move there. What happened?

Right, away from the ball the space is wide open. Every variant of zonal marking (with space squeezing, at least) results in open spaces, but in space-oriented zonal marking they arise throughout as a natural occurrence. They will also be so large that they can be played not only on long dangerous diagonal balls but, from halfway intelligent adversaries, through short passing combinations – as in this case.

In the game between Valencia and Malaga, Valencia tried this coverage to some extent and failed. In this article you’ll find a few nice pictures from laola1.tv including a brief explanation.

Option 4: Option-oriented zonal marking

With the option-oriented or even ball-oriented zonal marking, the reference point is the ball – how can it harm us, how do we prevent that? The team moves out of position differently, depending on the position of the ball and the opportunities that arise for the opponents.

This option was practiced by Laudrup’s Swansea and, to some extent, FC Barcelona. It is important that the players play smart and are well coordinated, otherwise numerous holes will be opened and the formation torn apart.

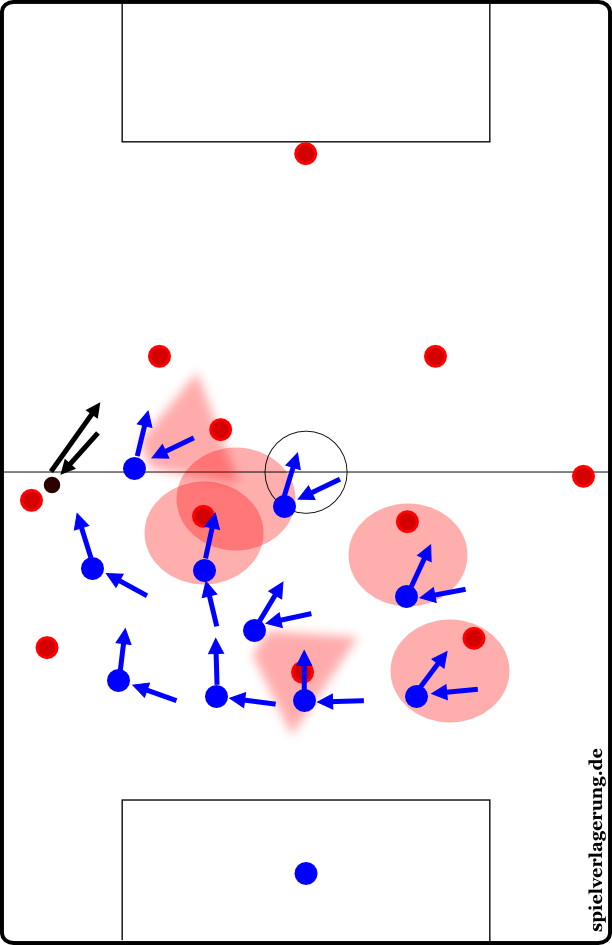

It’s the same scenario, but with different movements. The opponent passes to the right-back (“our” left) and our team moves. However, our right-back thinks, “Well, hey, if they play a sexy diagonal ball, there’ll be trouble” and breaks off from the chain.

Our left winger cuts off the opponent’s right winger in his cover shadow, while the left six prevents a dangerous pass coming to the opposing center-forward through the open space. The left striker cuts off the opposing right eight with his cover shadow. His partner, the right striker, therefore moves up in anticipation.

Why does he move up? We can see it in the attack development. The opposing right-back’s pass is risky, the left striker tries to intercept him, fails and runs wider; now cutting off the opposing right-back in his cover shadow. The second striker can now press and attack the opponent’s six.

Our team moves on, the far winger focuses on the flank. If we win the ball, he thrusts into space. If it is passed off, he covers the far side from diagonal balls.

Zonal marking as an individual

Under certain circumstances, zonal marking can be operated in mixed or man-marking systems with “space-markers”. Even if this is not the norm, we will dedicate ourselves briefly to two such options. Though the possibilities are probably endless.

Option 1: The Libero

The most famous free man in the history of football is the libero. He traditionally played behind a defensive line and had no opponent to mark, covering open spaces. The libero wanted to plug the many holes left open by man-marking. Behind the tempestuous man-marking line, the libero was solid as a rock; positioning himself behind holes in anticipation of intercepting passes or taking over from a vacating teammate.

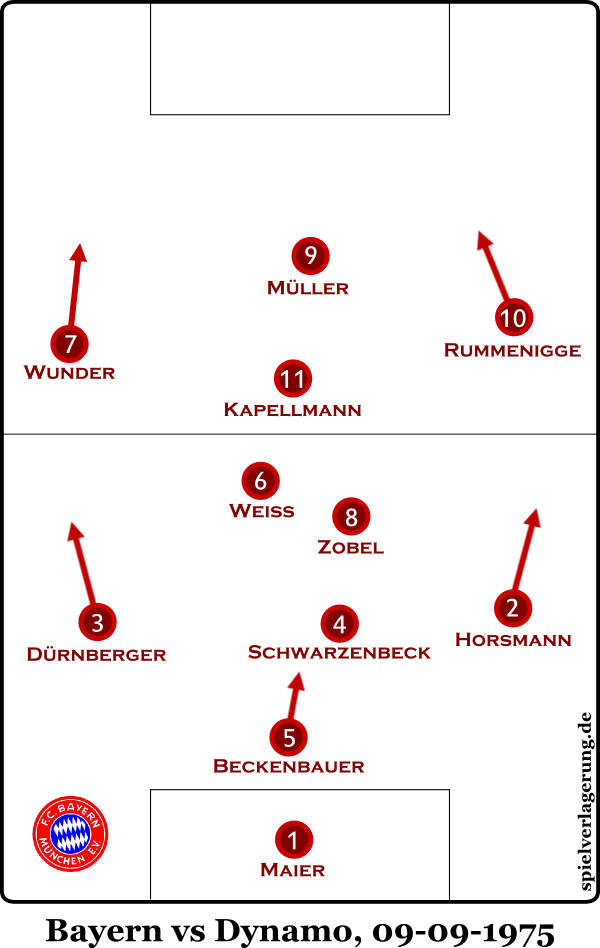

Bayern’s formation in the 1975 European Super Cup against Dynamo Kyiv, with Beckenbauer playing as libero behind a man-marking team.

Option 2: Space interpreter and zonal marker

Some players act as free agents in front of the defense; sometimes even in zonal-marking systems. They play a role isolated from the formation or a different zonal-marking than their teammates. So, a defensive six could be the only one in his midfield playing position-oriented, and thus hold his position while his teammates man-mark or organize their man-oriented zonal marking.

On the other hand, a ten could also play as a “hunter” and always orient towards where the opponent is playing. Then he would repeatedly swing from a number ten role to the half positions and make space there compact.

Anything else?

Actually, very much so. One can still incorporate a lot more reference points to put a greater emphasis on pressing and especially counter-pressing, and build new zonal marking options. Time coverage would be possible as well as ball coverage, structure coverage, Dynamik coverage and much more.

There are also tons of different variations to the previously mentioned zonal marking styles. These relate to movement, the involvement in the defensive work (see Cristiano Ronaldo’s “gambling”), the exact implementation of the defensive positional play, asymmetric possibilities, the defense’s behavior when switching to the base formation and back, etc., etc.

This list above is intended to provide only a general overview of the two large and two smaller uses of zonal marking; outside of these four variants, there are still ways to create new ideas; within these four variants there are also an incredible number of variations.

How does the chain move when a player leaves position to press? Does one press backwards, or return to their position? How exactly do you decide who presses backwards and what do the remaining players do in their positions? Who provides defensive security and when?

The possibilities are endless thanks to the countless combinations and the many complex facets of the game, Which is what makes football so incredibly diverse.

Even as a standard the use of a zonal marking system is not clearly defined. Most teams mix it up positionally. Using situational or flexible man-marking and varying them in the different phases of the defensive game. Starting from a position-oriented zonal marking against the opponent’s deep buildup in order to remain stable and organized, then, switching to a man-oriented zonal marking when the opponent is higher, in order to get faster access. During the pressing phase, they are then option-oriented and cover the potential passing lanes or something similar. As you can see, a defensive standard does not exist.

4 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Tom April 8, 2016 um 12:51 pm

Question about Lucien Favre Gladbach –

Would the central and wide attacking midfielders if moving between the lines be left in cover shadows to keep the structure intact or the lines converge?

Ahmed samir February 20, 2015 um 10:21 am

very nice article.Thanks a lot.I have a question which is which of those systems does barcelona apply under guardiola and luis enrique?thanks (:

simon June 14, 2014 um 12:22 am

Hey great article really enjoyed it. Any chance you could do a similar one about the different mechanisms in pressing?

Thanks a lot

Simon

RM June 28, 2014 um 9:26 pm

Thanks! What exactly do you mean with that question? I guess I could do it, if I understood it correctly.