Bayern Munich’s pressing in 2012/13

The media, all experts, and fans of both teams seemed to agree: In the last two seasons, Dortmund’s superiority was largely due to their superior tactics. Pressing or counterpessing – Dortmund simply knew how to do it better.

In this article, we will take a closer look at Bayern’s defensive strategy. We will examine their pressing from a tactical perspective. Exemplary scenes, a few statistics, and general tactical explanations will pave the way.

Two major transfers that changed Bayern’s pressing

In regard to prestige and money, Bayern has made three spectacular transfer-moves in recent years. Number one was the signing of Mario Gomez for a then record sum of 35 million €. Number two was the controversial signing of Manuel Neuer from Schalke 04, critiziced by some fans and the media. The third major signing (for € 40 million) was Javi Martinez. The Basque arrived this summer and was supposed to help the Bavarians succeed after a season of disappointments.

While Gomez is often criticized for his old-fashioned style of play, he does not feature in this analysis – primarily due to injury. Still, Gomez is by no means a static striker confined to the box. Especially under van Gaal he showed convincing skills in general and backward pressing, even if that strength decreased with time.

Javi Martinez and Manuel Neuer, however, are two players whose modern way of playing was probably never questioned. Still, both contribute to the defense in a covert way, which is why we will briefly address these two separately.

Neuer is probably the emblem of the modern sweeper-keeper – or, as in German, the “Antizipationskeeper” (“anticipating goalkeeper“). Sometimes, his style of play seems to be a bit too risky, even clumsy and spectacular. And sometimes, his genius doesn’t attract attention. The game of the DFB-team against the Netherlands featured an exemplary scene. As Arjen Robben receives a through ball, Neuer is already on his way. When Robben tries to get the ball in the box, Neuer lunges at him – although he misses the ball, it throws Robben off balance. Goal? No. A save against a non-crowded striker would have been less likely in a 1-on-1 from close range.

Take the game against Hamburg, where he disabled Heung-Min Son in the same way – he shifted the Hamburger into a worse position and gave his teammates time to run back. This does not always work – in the last season, Mainz (Ivanschitz) and Gladbach (Patrick Herrmann) scored each in a similar situation. In the first case, Ivanschitz was too cool and decisive, in the latter, Reus’ pass and Hermann’s good dribbling surpassed Bayern’s backward movement.

Neuer’s strengths, however, do not lie in his defensive abilities alone. In the closing stages against Italy, Neuer’s long ball was headed back, Andrea Pirlo passed the ball directly to the striker. There was no defender in sight, but Neuer (at the center line!) headed the ball back to the front. A dangerous counter from Italy became a renewed chance for the DFB-Elf.

The same happened in the closing stages against Leverkusen, where Neuer – after a weak ball reception, acting as centre-back – went into counter-pressing, won a dribbling in the last third of the pitch, asserted himself with a little luck and passed the ball to the side – if the Ball had not bounced off the crossbar, every Bayernfan would have erected a statue in Neuer’s honour.

He has outplayed Robert Lewandowski already twice this season: once when the latter was pressing in the League game (Neuer resolved the situation with a nice trick), and once when he ran out in the Supercup, indicating a long ball – and then he simply took the ball and passed it on to Boateng.

These actions and his control – sometimes up to 30 meters out of his box – makes it possible for Bayern to move out so aggressively, without any regard to the movements of the goalkeeper. This season only in the game against Gladbach we felt that his range was a bit extreme, even to our standards. Neuer always plays along and shifts with his team. His goalkicks, his drops, his reflexes and his irrepressible desire to win also strengthen the team.

Martinez’ play shall be highlighted by the analysis of two exemplary scenes from this season.

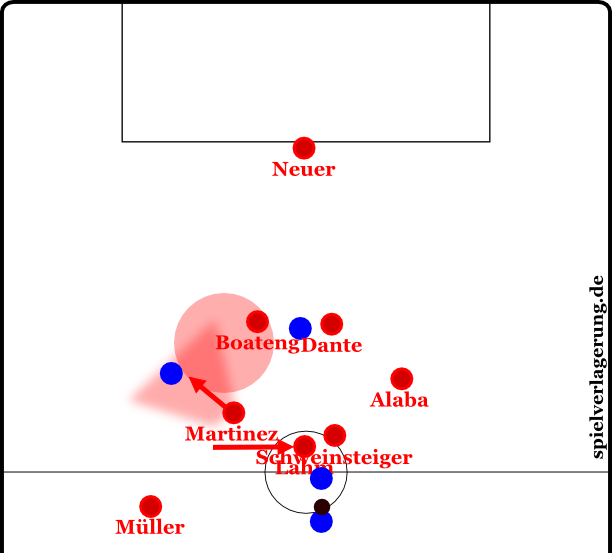

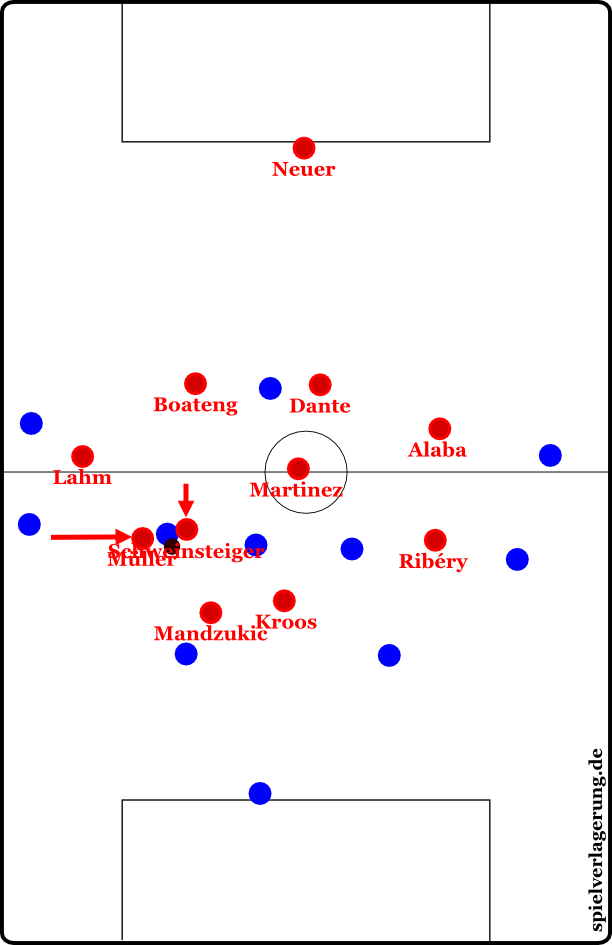

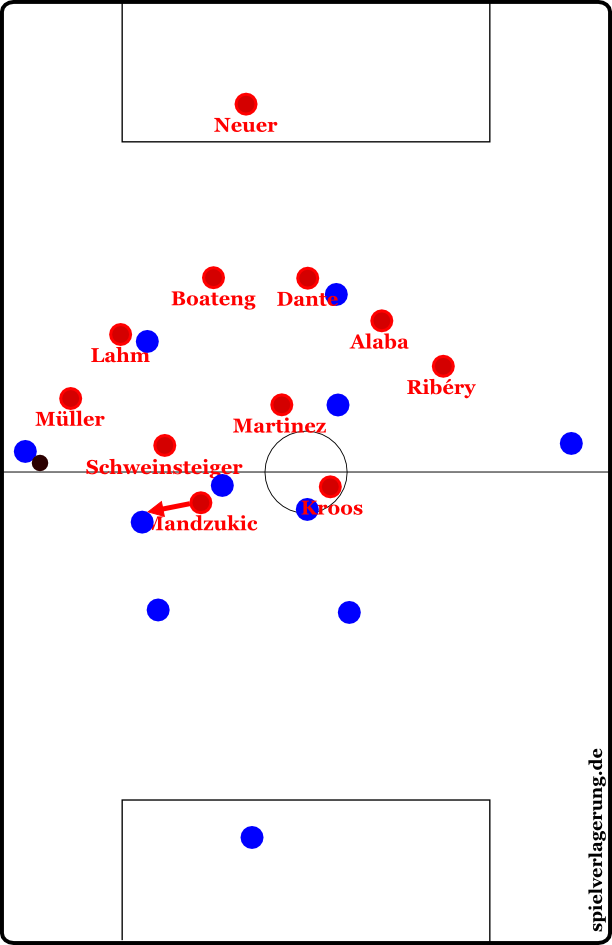

Here you can see how Martinez assesses the situation correctly and shifts to the side. Philipp Lahm had previously (in counter-pressing) led his opponent inside. Together with Bastian Schweinsteiger, he blocked the paths into central midfield. Thomas Mueller rushed back, but Martinez had already seen the hole and moved instinctively to the rear.

The HSV had no chance to finish their (out-manned) counter, and Jerome Boateng was able to stay with their center forward. This situation offers various hypothetical but interesting theoretical aspects: if the ball had still been passed through successfully, Boateng would still have had access to it – just like Martinez. Boateng blocks the pass route inward, Alaba moves to the center, and Thomas Mueller assists. Two HSV players act against five Bayern players, three of them attack the man on the ball.

Had he played the ball towards the centre, the striker would have been matched against two players. If Martinez had not moved (as he did), Boateng would have had to swerve. A successful long ball or a fast forward pass to the center forward would have been possible.

There is another scene that shows a hidden strength of Martinez. In an interview dealing with Martinez’ signing I said a few months ago:

“Martinez is insofar another type of player as his focus in defensive play is entirely on winning the ball, instead of thwarting aggression. Thanks to his athleticism and technique he can (when possible) join in the attack, even though this is risky and needs intense running.”

(In my defense: “entirely focused” meant of course apart from tactical fouls. Otherwise he would have cost twice as much.)

In the match against Valencia we witnessed the following scene that underlines this opinion:

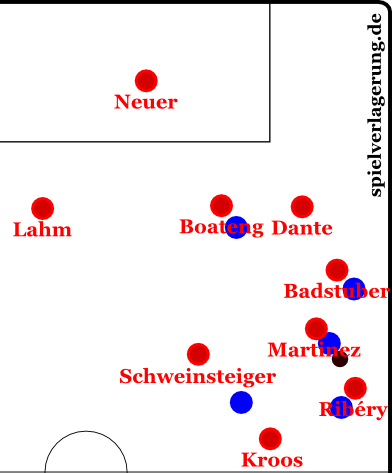

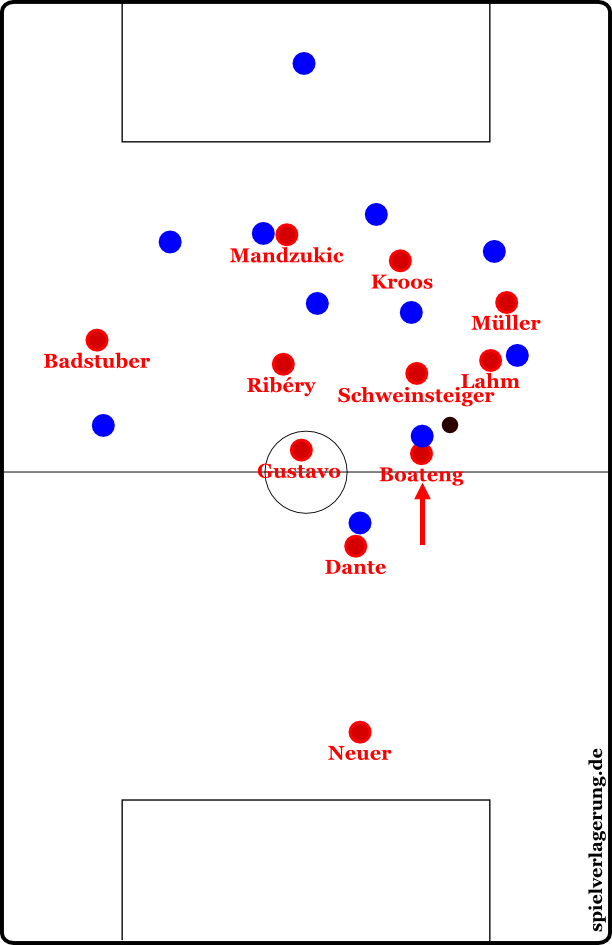

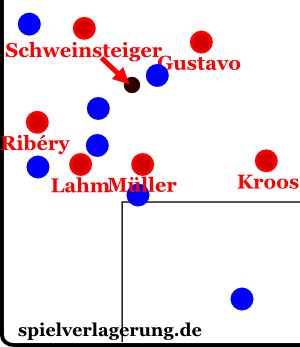

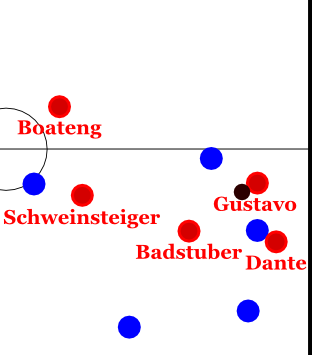

Holger Badstuber at left-back shadows an opponent. Behind him, Dante shifts to close down space, while Jerome Boateng is also looking for an opponent he can cover. In the immediate vicinity of the ball, similar things happen. Franck Ribéry has just pressed an opponent whose frontman received the ball. Bastian Schweinsteiger blocks the center. The only option, albeit a difficult one, is the free player between Schweinsteiger and Kroos. But Valencia’s player cannot even pass the ball, because Martinez attacks him tremendously skillfully from behind.

Martinez does not only take him off balance, or just the ball away. He toe-pokes the ball, so precisely planned that it ends up with Ribéry. There is no loose ball in space (a 50:50 position) or a ball out (possession for the opponent), but it remains with Munich. Now, Ribéry has several options. He can pass to Schweinsteiger in the center or move the ball immediately far back to Lahm or Neuer. The ideal option might have been to Schweinsteiger, but he was obviously not in Ribéry’s line of sight. The Frenchman opted for a turn and a dribble, resulting at least in a throw-in for Bayern and thus possession.

Martinez is not more effective in thwarting attacks than Luiz Gustavo. But he is more effective in winning the ball. Many of his tackles result in ball possession – rather than in 50-50 situations or ball possession for the opponent, and thus in a worse starting position.

In addition to the Basque and Neuer, there are two other transfers that increase Bayern’s quality in pressing – or, at the very least, increase the B Team’s quality in this regard.

Pressing Transfers Number 2: Dynamic Play

Dante’s signing from Borussia Moenchengladbach was suspected to be one of those mythical Bavarian transfers, made only in order to weaken the competition. Judging from the time Dante has spent in the starting XI and from his profile it’s safe to say that nothing could be further from the truth – even without consideration for the situation of the club when he was signed, or even his specific contract details.

Dante was bought by Bayern because he is a central defender the team needed desperately, especially a few years back. Martin Demichelis always lacked concentration a bit. Lucio lacked the intelligence to cover large space. Daniel van Buyten is sometimes too stiff and sedate to qualify for highest honours. Breno’s signing was meant to be a response to these needs: a technically strong, two-footed, even (if somewhat well-fed) outstandingly athletic defender was hired for the future.

Ultimately, he lacked the mental attitude (so very important for a defender) and was even unlucky into the bargain, but it still meant that the powers that be in Munich had already assessed the weaknesses of the team.

Later on, Holger Badstuber was promoted by Louis van Gaal. Jerome Boateng was signed. Badstuber is no Usain Bolt on the first few meters, but surely superior to Demichelis and Van Buyten. On long distance runs he is certainly fast (like Pique), although this opinion (and a reference to sprint tests at Bayern, with Badstuber in the top-5) will certainly provoke some chuckles.

In this regard there no divided opinions on Jerome Boateng. He is big, fast, and athletic. Dante, as an additional option surpassing Daniel van Buyten, certainly fits into this scheme. He is not quite at Boateng’s level, but for a central defender of his size he is certainly one of the best in the league on his position– and as a runner, too.

The speed of these players lets them cover large spaces, and they serve as a secure protection against counterattacks. At the same time, they can very proactively use their intelligence, athleticism and strong tackling. Another exemplary scene:

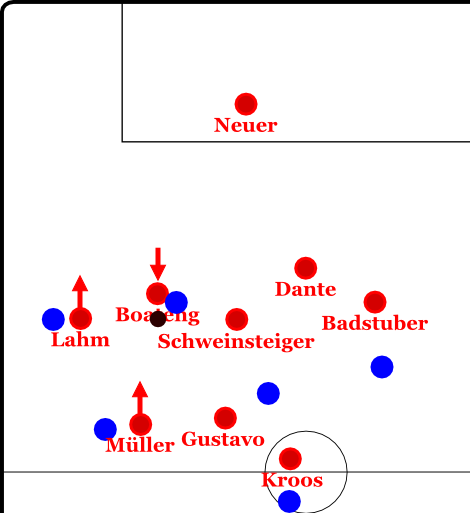

Düsseldorf try a counterattack from the left. From there, the ball is passed to the center forward. Philipp Lahm tracks his opponent (man-marking him on the inside), trying to block a pass into space. Gustavo has access to the midfield player, while Thomas Mueller rushes back on the right side. He intelligently puts his opponent into covering shadow. Thus, the tactical means of letting the ball drop or abtropfen lassen/prallen lassen in German (which means quickly passing to a teammate with only one touch of the ball, mostly after hard fast passes or with their back to the opposition’s goal) cannot be used. Bastian Schweinsteiger fills space in the center and covers just in case for Boateng who shifts aside. Schweinsteiger anticipates the pass, pursues his opponent and is even ahead on the ball, destroying Fortuna’s attack.

In the next scene we see this movement as well – bur now, it’s not defensive pressing, but counter-pressing in the opponent’s half.

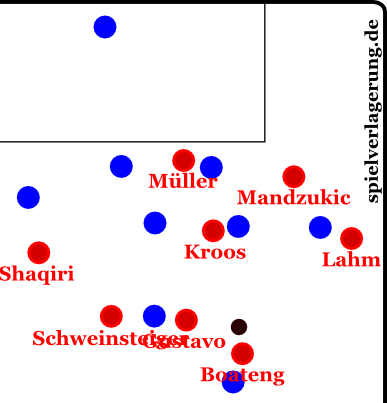

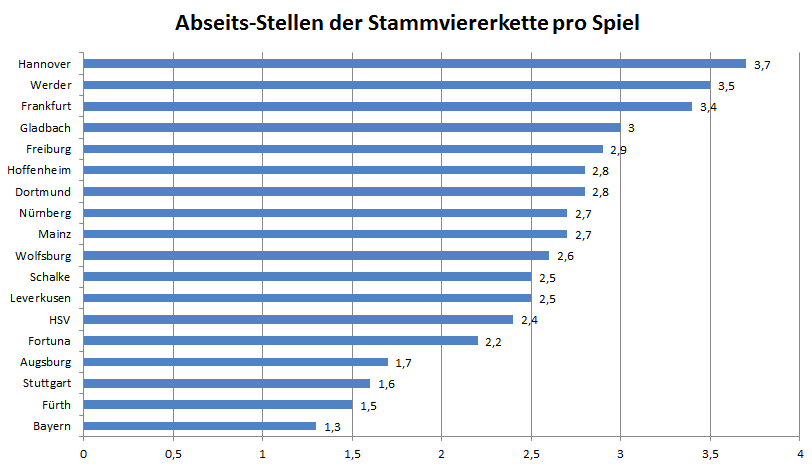

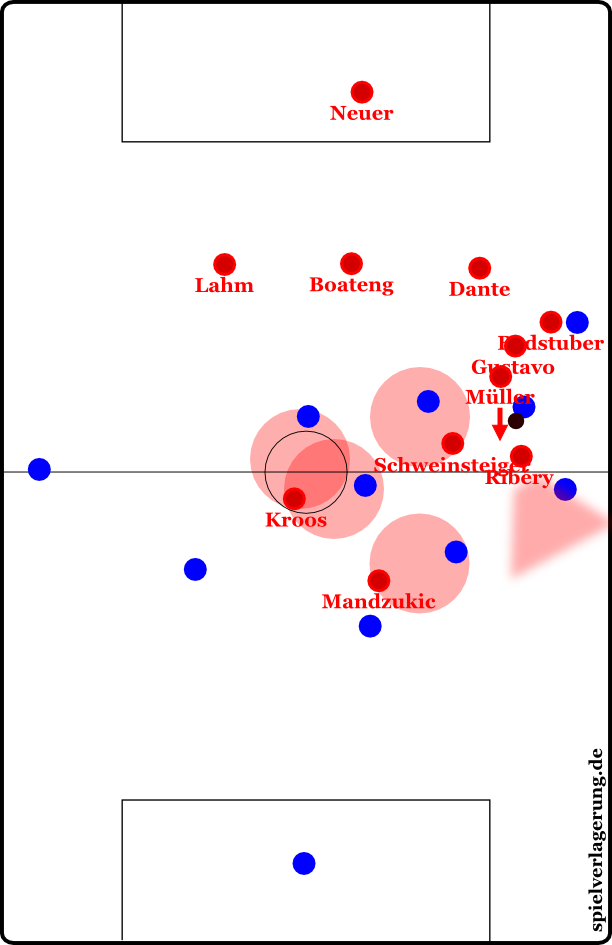

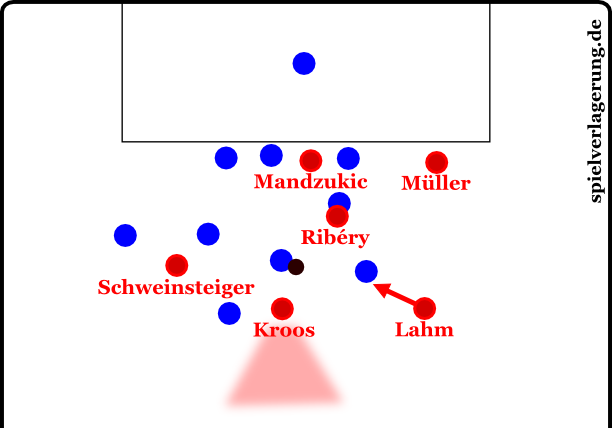

In this graph you can see Bayern having moved up in the match against Thomas Tuchel’s Mainz. Lahm is supplying the desired width in the third part of the field while Thomas Müller pushes into the center. After the loss of the ball Mainz tries to open up through a vertical pass and to attack Bayern’s pushed-up formation. All midfielders (including Mandzukic and Lahm) are in the last third of the field, leaving very wide spaces free for a counter from Mainz.

The counterattack has problems to face, though. There is a lack of width, a lack of space, a lack of time to process the situation. A well functioning counter-pressing is therefore not only the best playmaker, but also the best safeguard against counterattacks, and the basis for aggressive play.

In this game, Bayern practiced this mode of play in a way that, in this scene, it is even Boateng who pushes forward and captures the ball. He overtakes his opponent and is clearly the first on the ball. Bayern thus prevent a counter attack and start a new attack themselves – Boateng compressed the space around the ball a little bit further just to make this possible.

At the same time, this scene points at a little speciality Jupp Heynckes came up with.

Bank of four without playing the opponent offside?

As already stated: Dante and Boateng are strong in the air, excellent tacklers, and very fast on their feet – at least in long distance runs. Bayern’s offensive formation in ball possession also requires outstanding coordination, so Heynckes curbed line play (staying on the same horizontal line as it is usual in a back four). The Bavarian defenders still act as a bank and shift in orientation towards the ball, but they use man-marking again and again without provoking offsides.

This scene features an extreme example. Düsseldorf tries to counter. Because of Bayern’s fluidity, the left side is left wide open. Badstuber rushes back. In this situation, two major problems may arise.

- If Boateng remains behind, the pass receiver might turn and pass into the free space on the side.

- If Dante goes forward, a blind and imprecise long ball or a standard extension into space might be dangerous. Playing at offside is always risky.

So both situatively man-mark their respective counterparts. Dante stays deeper than his opponent, offside is of no interest – if your defenders are combative and quick, a running duel or tackle 40 yards from the goal is probably more promising than hoping for an offside situation. A maximum vertical space compression is not necessary out of principle.

In this case, Boateng succeeds to do so alone, without Dante. Boateng even captures the ball in this scene. The ball is close to five additional Bayern players in the immediate vicinity – ball possession is a mere formality.

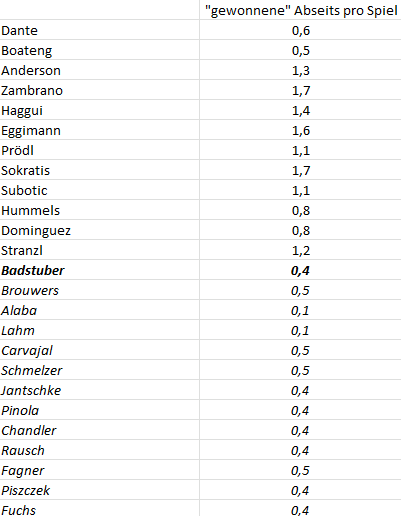

To substantiate these statistics of a move away from defensive play on the line, we compare the respective defenders of the league using data from Whoscored.

So far, Dante “won” 11 offsides, an equivalent of 0.6 per game. Boateng won 7, or 0.5 per game. Thus, they are clearly the weakest central defenders on this list. Only Mats Hummels and Alvaro Dominguez are also below 1.0 offsides won per game (at the time we took the data in autumn).

Even Bayern’s full-backs are at the bottom. Most offensive full-backs in the league win 0.4 or 0.5 offsides per game.

A list of offsides “generated” by fixture back fours per game should counter possible fluctuations due to missing full-backs or similar factors.

Here, Bayern are way at the bottom. It is noticeable that Nürnberg and Augsburg are near the bottom, two rather deep-playing teams that use man-marking now and then. In addition, all three teams below a 2.0 value (excluding Bayern) are in the top 6 regarding goals conceded.

Conceded goals and little or weak offside generation could be linked. One explanation might be that poor defensive coordination creates less clear offside situations, and thereby more goals are scored. But this does not hold true for Bayern. Is it due to ball possession? If you have the ball, the opponent cannot attack. But in the Spanish league, FC Barcelona’s defense creates 2.1 offsides per game, significantly more than the Bavarians. Even when extrapolating the whole collective (and not just the regular defensive line), the Bavarians are still clearly “inferior” with 1,765:2,125 – at much less ball possession (63%: 69%).

This suggests that Bayern do not care for offside. They represent a certain novelty and practice it successfully.

Besides these signings in defense and in midfield, and the changing styles of play, there is another new pressing player in Munich’s team structure.

Pressing transfers Number 3: Defending strikers

When Ivica Olic signed with VfL Wolfsburg not too long ago, some Bayern fans mourned his loss. In the van Gaal era he had contributed to Munich’s success in the Champions League 2009/10. His goals had helped secure the double. His strong running skills and his will to work had won the hearts of the audience.

His compatriot Mandzukic was signed this summer. He is a similar player and came from Olic’s new club, VfL Wolfsburg. Mandzukic is not quite as dynamic as Olic and does not work as tirelessly. But he is stronger in ball retention, more dangerous in scoring and a bit more intelligent in game positioning. Let’s have a look at this scene:

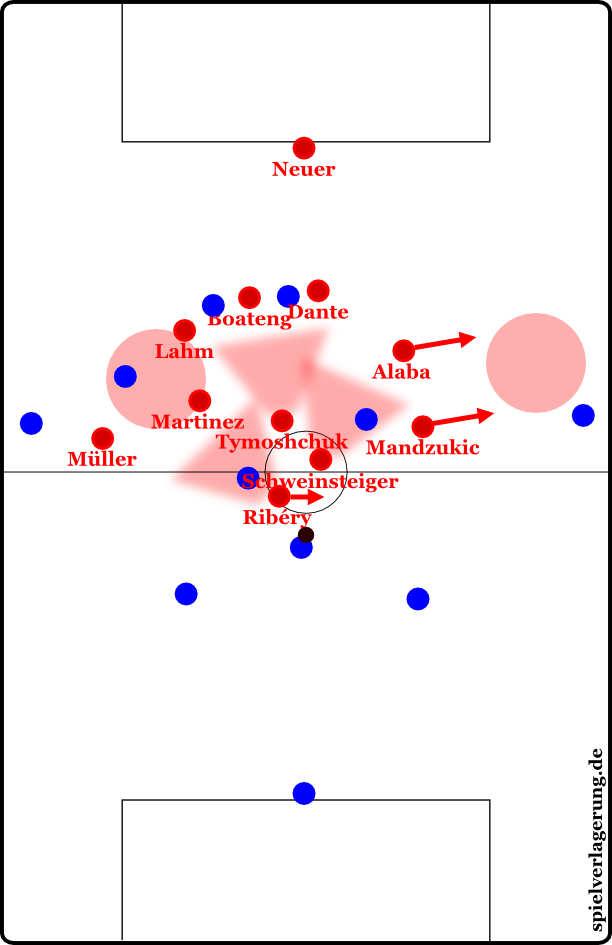

At first glance, it is immediately apparent how Bayern press – it’s interesting and seemingly disorganized. But Anatoliy Tymoshchuk takes cares of space to the rear with his covering shadow, preventing a flat sharp through ball (with a possible second ball). If Tymoshchuk had filled the hole David Alaba had consciously opened, a flat pass would be possible and could be played along behind Schweinsteiger with one touch.

Schweinsteiger takes over Kroos’ role while Ribéry instead of Mandzukic acts as striker in pressing. Mandzukic has already filled holes on the sides on several occasions, due to his role as a swerving striker in offensive play. His intelligence and athleticism allow Bayern a fluid playing style. After ball losses he joins either the counter-pressing atttack or moves on to an outside position. Now and then he even plays like that without regard to fluidity, just to give Ribéry the chance to gamble.

In this scene you can see how Mandzukic enables flexible pressing play. In this scene he even starts (together with Alaba) to move before Hamburg’s deep-playing Six (DM) has passed the ball. Thus, they lead the opponent into a pressing trap. Hamburg tries to use free space, but Mandzukic catches the ball and immediately launches a counter attack.

Still, the Croatian striker is not only extremely important as a “filler of space” and as a swerving striker. He is also convincing in “normal” attacking pressing.

Here, Müller’s and Schweinsteiger’s paths are impressive. Their paths converge intelligently and press the player in ball possession. But besides anticipation (again!), the synchronized movement and Müller’s covering shadow, Mandzukic’s preparatory work is crucial in this situation.

His arc-like run blocked the pass route to the second central defender. For this purpose, he kept track of the pass route to the Six. When the central defender turned his field of vision, Mandzukic attacked him. The opponent’s supposedly free Six could therefore be circled, and Bayern won the ball. Martinez secured the centre. Ribéry and the full-backs came inside and cut the possible passing connections while Kroos moved in behind Mandzukic.

Mandzukic’s role is not the only flexible one in Bayern’s system. There is another sort of flexibility in the backing up of the full-backs, which of course affects counter-pressing in different ways.

Backing up the fullbacks

Bayern often use the central defender to push behind the full-back as a back-up. There are different ways to do this. Some teams let the Six tilt back between the central defenders and play a situational back three. Others let the centre-backs shift and keep the full-backs deep, retaining the “Six” in the middle.

All this has its advantages and disadvantages, which we discussed briefly in this article.

In that article we also mentioned that Bayern act with a mix of the above as their solution. The graph above features one exemplary scene. Against Fortuna, an example of a different way of playing can be seen in this scene:

Six Bayern players are in a confined space, including the two Sixes. As Lahm started his run, Schweinsteiger shifted intelligently to his side and filled the hole. This position was too high for a central defender – if his name wasn’t Boateng (and had a good day into the bargain).

After the ball loss Schweinsteiger could immediately move on and intelligently intercept Stuttgart’s forward pass. This even resulted in a good chance for Bayern (that Kroos blew). We see once more that counter-pressing is the best playmaker.

This way of playing is both a pro-argument for defensive back-up by a Six and for Bayern’s play with a central defender. Schweinsteiger impressed here by his zone defense, back-up, anticipation and intelligent movement. On the other hand, Munich’s compactness is impressive here, and Schweinsteiger’s free movement is also made possible by his high position. This “mixed solution” fits very well – in part because it produces compactness well.

Local compactness

A particularly interesting situation arose in the game against Düsseldorf when five Bayern players (postioned very laterally) attacked.

At first, Müller acted centrally in pressing. Kroos was positioned on the right side. You can see the positional flexibility in Bayern’s defensive play very well: not only can Mandzukic play to fill space, but Kroos, Müller, Schweinsteiger and Martinez can do so as well.

After a long goal kick the ball went to the right side, and the team immediately shifted aggressively. After successful ball handling and a short pass by Fortuna a situation was generated where Gustavo did not provide back-up but rather increased compactness.

Then, Müller intelligently reacted and blocked the pass route to the centre. He moves forward and does not press, but instead immediately blocks the pass route to the Six. Afterwards, he can easily attack. Ribéry tries to put the full-back into covering shadow, but the latter runs free and receives the ball. Now, the compactness increased by Gustavo came into play: the fullback isn’t able to play a pass and has to shoot at Gustavo.

It is also interesting that Schweinsteiger, Kroos and Mandzukic let their opponents be but still have access to them. Kroos is positioned in a way that he can attack both players if passes to the middle should occur. Winning the ball is not likely here, but this system destroys Fortuna’s attacking possibilities.

Another example, another game, in another part of the field.

Alaba leaves his opponent in covering shadow and goes for the player in ball possession. From behind, Ribéry helps. Turning is not possible. The opponent cannot use the pass route inwards, because Martinez barrs him and Schweinsteiger man-marks an additional Hanoverian. Thus, a forward pass is the only option – however, Alaba manages to play the ball out of bounds.

Had the line pass come through, it would probably had been taken by Badstuber; or at least he could have diverted the opponent’s attack. Dante and Lahm would have secured the centre. The enormous and risky compactness on the side, however, paid off again, and there was no shifting required. Avoiding shifts by anticipatory movement and the generation of local compactness can also be observed beautifully in counter-pressing.

Counter-pressing

Munich’s adaptation of allegedly Klopp’s invention has probably drawn most attention this season. On good days, their play against the ball was outstanding, and in the current league season even above the level of the BVB (according to some fans). We will discuss a few exemplary scenes to illustrate how it was played.

Again, six Munich players have ventured far into the opponent’s half. After an intercepted pass (intended for Ribéry starting in the centre) has resulted in a ball loss, a Fortuna player has the ball. Kroos blocks the simple pass option forward into the top. But next to the Fortuna player there is a free player who does not have this problem. Kroos presses, but the Düsseldorfer can play the ball to the side, and Kroos has opened up space behind.

Here again we can see Lahm’s sophistication and Heynckes’ guidelines. Instead of returning to his position in defense, Lahm shifts into the middle and puts pressure on the free pass receiver. The latter cannot turn and has to play a quick pass across. Due to Kroos’ moving up the player freed by exactly this movement receives the ball, but now there is another problem: Bayern’s clever Bastian Schweinsteiger was also man-oriented and takes the ball.

He toe-pokes it on to Kroos who plays on to Lahm. Lahm continues the attack. Ribéry remains centered, Müller stays wide and Lahm heads towards the centre as befits his role as a play-making diagonal full-back. The ball is circulated handsomely, Müller and Ribéry increase movement and open space for Lahm, but Ribéry is fouled dribbling.

There are other games besides those in the league that feature such scenes. Counter-pressing was also used in the Champions League.

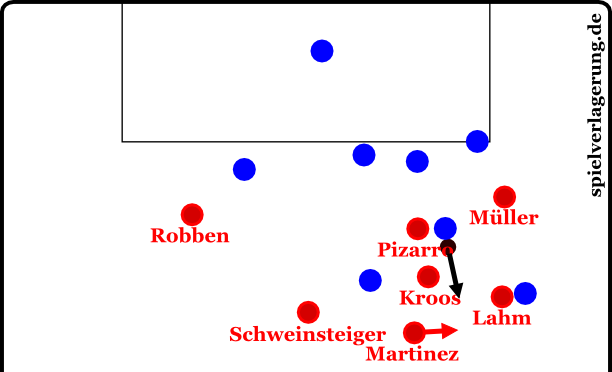

After a ball loss by Pizarro the player in possession is immediately put under pressure. Pizarro turns, Kroos compresses the game and Lahm on the inside track blocks the pass route to the next wide player. The Valencia player therefore has to play forward.

Once again we see the advantage of a Six who does not concentrate outwards in back-up play. Martinez can use his skills and intercept the dangerous pass to the top. Bayern – this time with seven players up front – use compactness and get the ball. Counter-pressing does not only consist of orientation towards the ball and immediate pressing after ball losses, but also requires an appropriate positioning.

And while we’re already speaking of formations and positionings, let’s take a look at two tactical aspects in the basic formation of Bayern Munich.

Basic formation: the wingers’ tasks and vertical compactness

Bayern Munich’s wingers act peculiar in defensive play – they run a lot in reverse pressing, they position closely in pressing, and sometimes they stay very deep and secure space. Here is an example from the game against Hamburg.

Thomas Müller falls back and attacks, Ribéry is positioned deeply and off the ball in order to secure space. Schweinsteiger is positioned higher than the two and retains access to the opponent’s Six. Martinez secures the middle in front of the defense.

Mandzukic and Kroos are located at the front as strikers, but both do not push on the centre-backs, but rather on a line in front of them. They increase compactness and access to the opponents. In such situations, the opponent is forced to pass to the other side where Ribéry’s deeper (for a winger) and Alaba’s higher (for a full-back) positioning comes into play.

Alaba does not interfere with the centre-backs’ rare offside traps and does not have to adhere to a play on a strict line. Ribéry is able to intercept diagonal balls well and thus can immediately switch to an offensive game. Thus, he can attack the empty space behind the wing player very well, and Alaba can offer support.

In this situation, Hamburg did not go to the other side. A few seconds before, Müller had intelligently run into the depths, so the full-back had no pass route forward or sideways and had to play backwards. Mandzukic attacked the pass recipient. A long high ball into the top followed, Philipp Lahm intercepted.

Basic Formation: Kroos’ role

The especially interesting formation feature concerns Toni Kroos. He is currently the main central offensive midfielder. In pressing he often acts as a second striker, generating a situational 4-4-2.

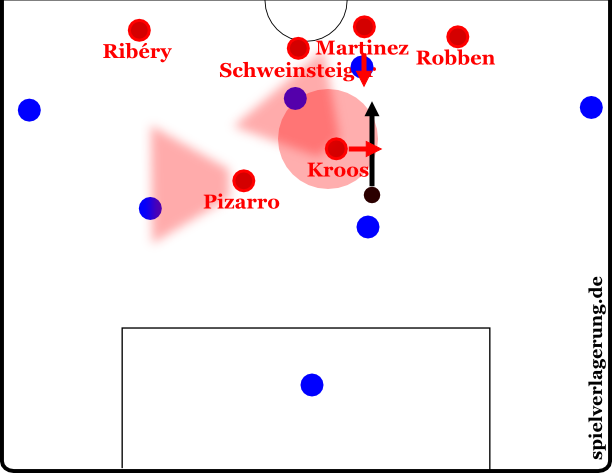

In this scene against Valencia, he pushed forward slowly and carefully. He kept the pass routes in mind and the opponent’s Six in his covering shadow – in addition, that player got man-marked by Schweinsteiger. Pizarro’s covering shadow and Robben’s careful observation of the full-back made the central defender mistakenly try to play a pass somewhat to the right, towards the Six in front of him in space.

Martinez had waited for this and pursued the Six aggressively. Kroos did that as well. The pressing trap snapped shut, Kroos intercepted the pass and got the ball for Munich, deep in the opponent’s half, against a fanned formation.

Liberation from counter-pressing

Finally, we would like to present reflections on the reaction to a ball loss before moving on to the statistics.

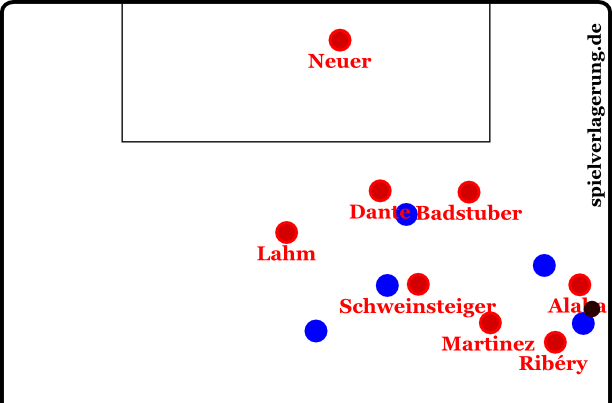

An attempted pass by Badstuber failed to reach Xherdan Shaqiri in the opponent’s half. Badstuber immediately shifts to the rear. With an inward movement, he can deflect Mainz’ pass to the top. The deflection was skillfully made and planned – by no means a coincidence. Although Badstuber probably did not know who was positioned where, he assumed that a precise pass had been played. He deflected it “on principle” to the other side – a good guess.

He thus forwards the ball to Gustavo, who has to go into a tackle with the originally intended pass recipient. Dante helps and collects the loose ball, but a Mainz player toe-pokes the ball away, resulting in the situation depicted in the graph.

Now, Bayern start playing. Gustavo passes to Badstuber who recognizes the triangle and immediately passes to Dante, who in turn plays to Gustavo. Three passes were played in two seconds. Even the compressing shift of two Mainz players was of no avail against this. On the contrary, Gustavo turns and plays Dante’s pass casually on to Boateng free in the middle. Thus they freed themselves with skill and cunning from the really good counter-pressing employed by Mainz.

Summary and general observations

- • 4-2-3-1/4-4-2 in pressing• On occasion the “original” 4-2-3-1/4-3-3 shifts to a 4-4-2, a 4-1-4-1, a 4-1-3-2 and a 4-2-4 – 0

- • The striker (close to the ball), Kroos or another central midfielder can create a 4-3-3

- • Very flexible: Kroos, Müller, Mandzukic, Schweinsteiger and Martinez as “space fillers” and stand-ins for vacated positions

- • Martinez, Ribéry and the collective as such as “counter-pressing genius” and / or liberator from counter-pressing

- • very fast reverse pressing, return to positions, especially by Schweinsteiger and wide players

- • The return to positions can be interrupted repeatedly in counter-pressing

- • Very intelligent movement of the collective, but especially of Müller, Lahm, Schweinsteiger and Martinez; Gustavo and Mandzukic convince as well• Excellent central defense• No line play, rather tackles instead of risky offside play• Variability in central shifts, partially Schweinsteiger instead of Kroos as offensive player if a shorter path presents itself• Mandzukic very strong in pressing, good in reverse movement. Partially takes over vacated positions (e.g. Ribéry) if fluidity was applied before in the offensive

• Aggressive man-marking of strikers in high counter-pressing situations

• Tactical fouls, especially by Martinez and Gustavo

• Local compactness (Lahm/Müller/back-up Six) instead of Lahm/Müller/gap to the next central defender (or similar)

• Zone killing à la Swansea by covering shadows and partially passivity up high on the field, but with extra deep space control

• Tilting central midfielder (Schweinsteiger) helps on the side and does not stay in the center

• Very good space control against opposing wings, especially by Martinez

• If need be: central defenders spread, defensive midfielder falls back, situational back three

• Many 2-3-positionings with backward pressing full-backs and a deep lying Six in preparation of counterattacks

Statistics

Those not interested in dry stuff, interesting numbers and the interpretation of said numbers from a tactical perspective may now switch back to filthier websites.

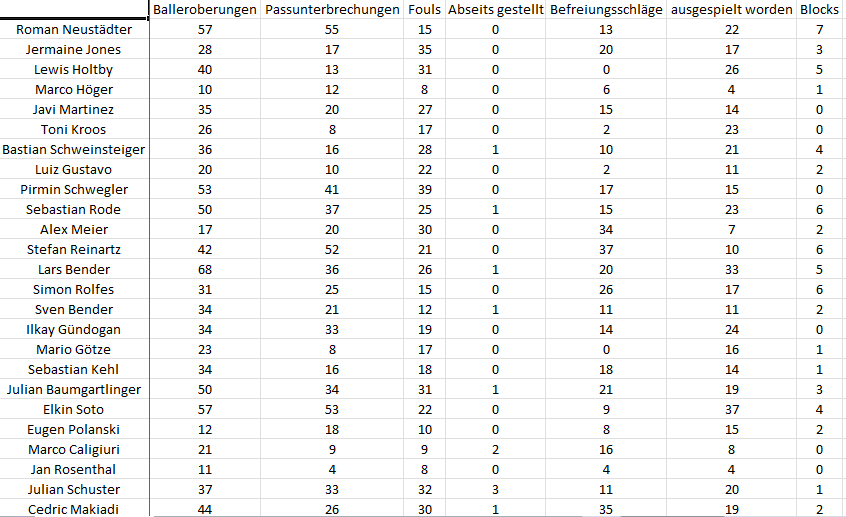

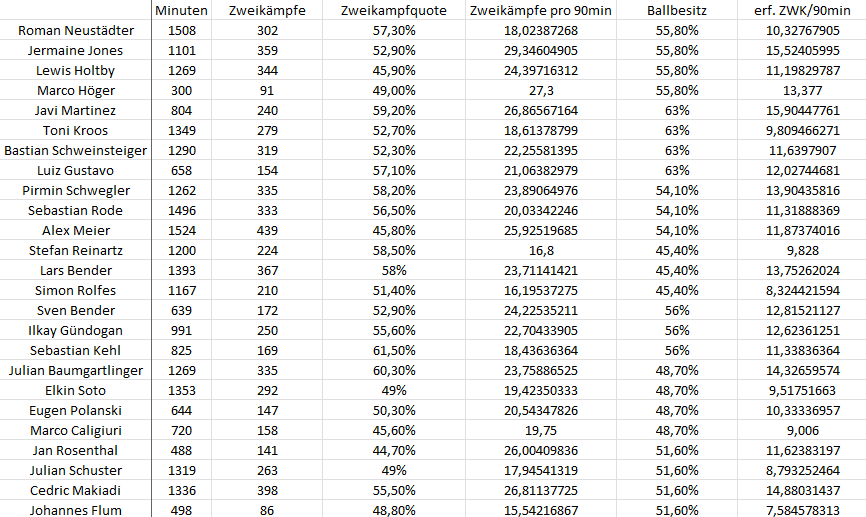

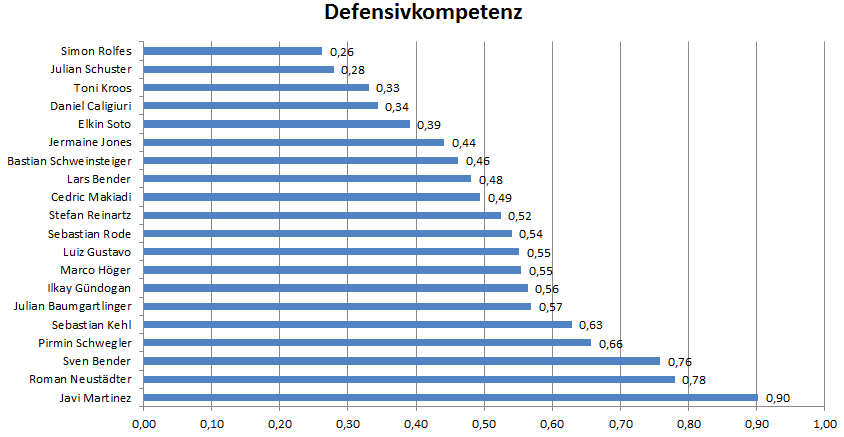

For the analysis I have compiled a database with data from Whoscored.com, concentrating on the most important defensive midfield players of the top clubs in the league.

Here you can see the individual players’ balls won, pass interruptions, etc. These values then were set in relation to the playing time of the individual players, the ball possession of their respective team, and their success rate (ie, fouls subtracted, etc.).

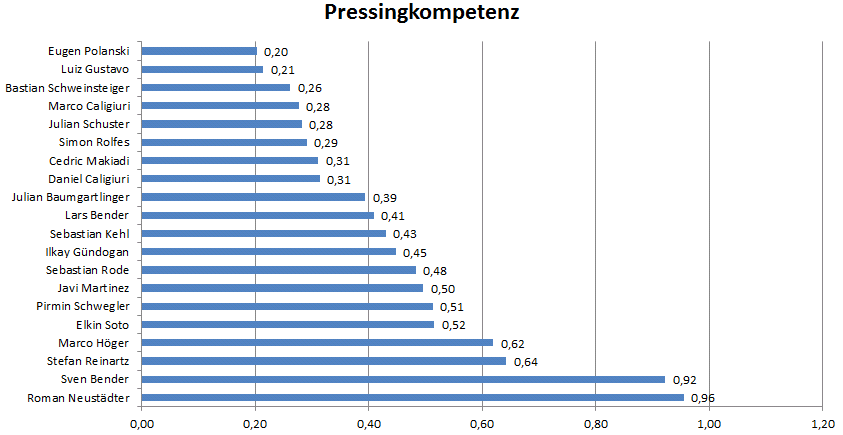

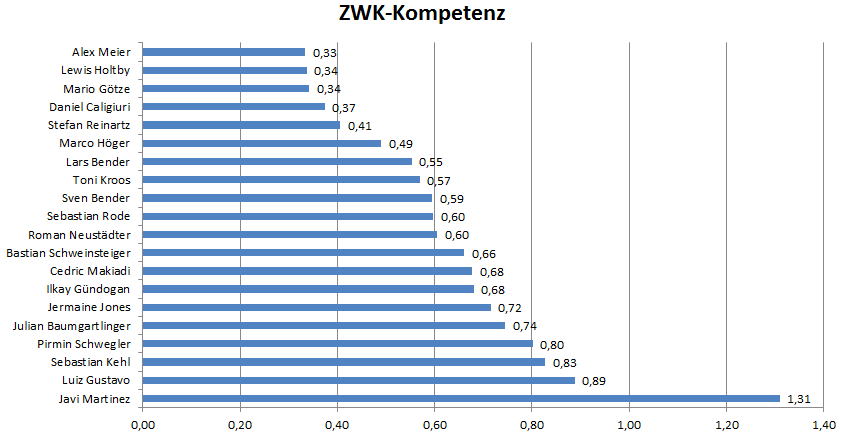

We call the result “pressing competence”.

This “pressing competence” shows that Roman Neustaedter is the strongest in his team and in the league. His teammates Jermaine Jones and Lewis Holtby are not in the top 20 shown here but among the last five.

Javi Martinez on the other hand is placed seventh, Bastian Schweinsteiger 18th and Toni Kroos is in the vicinity of Jones and Holtby.

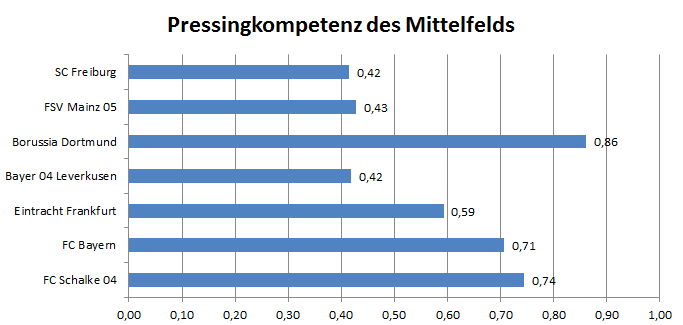

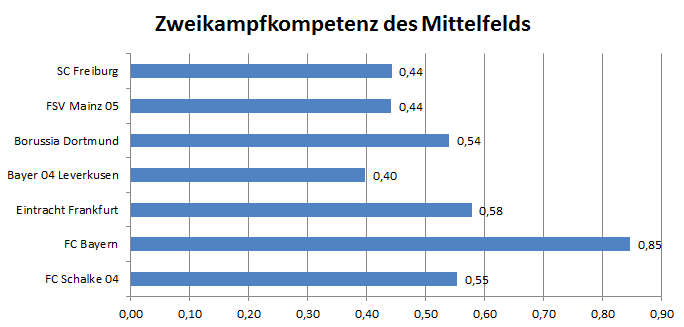

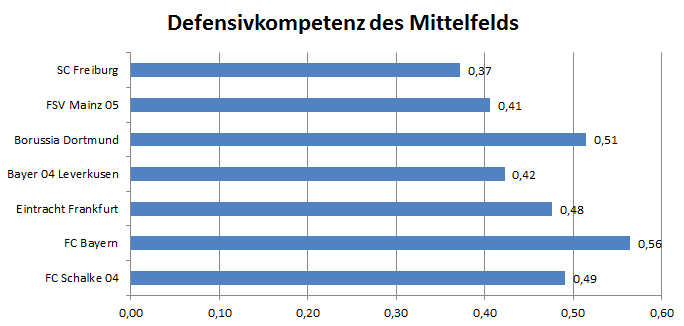

However, it could be possible that Munich’s dynamic pressing on more offensive positions (Schweinsteiger and Kroos) leads to the passing of a lot of balls to the central defenders, the wide players and Martinez. This is why we have another chart averaging three midfield regulars per team, factoring in (in turn for each player) the respective team’s ball possession.

That way, Dortmund still remain on top of the group. Bayern, however, were able to gain on Schalke. Yet, this still does not explain why Munich concedes so little. Is Manuel Neuer really that good? And why haven’t Jerome Boateng and Dante already won the ballon d’or? The answer must be out there somewhere…

And we have it.

Whoscored’s data does not include running duels, tackles, the battle for loose balls, etc. This data is supplied by kickwelt.de (where in turn the data supplied by Whoscored is missing). So I compiled a second database with data from Kickwelt.de.

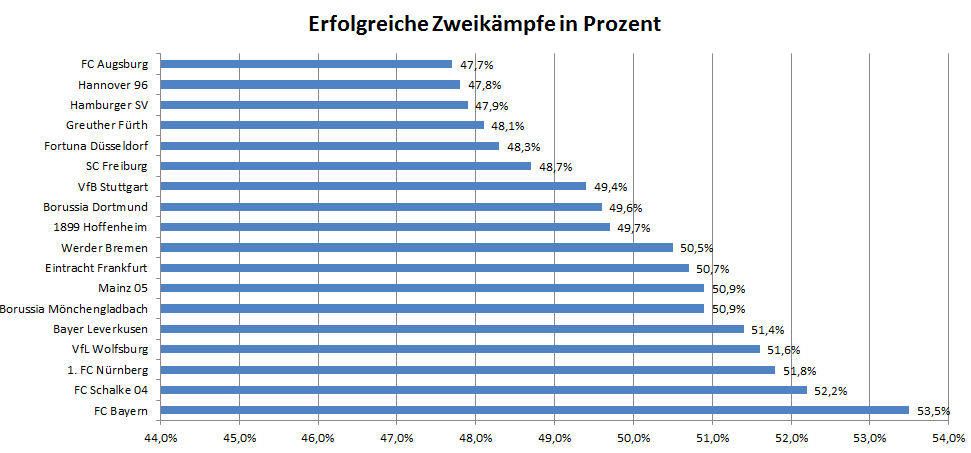

Won Tackles/duel data from Kickwelt.de is available for whole teams, with the Bavarians as clear No. 1 but Dortmund below league average.

Readers of Spielverlagerung.de know that we are not satisfied to just let the discrepancy rest (compared to the table situation, the statistics concerning conceded goals, and the factor “pressing competence”).

I have therefore included the absolute numbers of tackles, their success rate and ball possession, which resulted in the statistics “tackling competence”. This way, even probably fluctuating form of the respective players should be compensated in the long term.

For example, Alaba (15.2 tackles per game at a 59.2% success rate), Martinez (16/game at 59.2%), Schweinsteiger (19/game 52.3%), Kroos (16.4/game 52.7%) and Mandzukic (20.7/game and 47.6%) tackle most and have the worst success rate. No one is above 60% and has less than 15 tackles per game, while Dante (13.6/game 60.8%), Lahm (12.4/game, 63%), Boateng (11.7/game at 65 , 8%) and Badstuber (9.6/game 67%) are all players with less than 15 tackles, but a success ratio above 60%.

I wanted to compensate this imbalance by including the midfielders from the top group.

Roman Neustadter (always using brains more than brawn) is located in the upper middle, but behind Jermaine Jones. Bastian Schweinsteiger is in between, by far in front is Javi Martinez, followed by teammate Luiz Gustavo. The low pressing competence of his competitors appears to correlate with his tackle ratio.

Considered collectively, Bayern are now far ahead while Frankfurt is in second place.

But as “tackling competence” is hardly significant in itself, we have added tackling competence and pressing competence.

The result is what we may call “defensive competence”.

Up front: Martinez, followed by Neustaedter. Sven Bender and Pirmin Schwegler are next. What about the collective? Considered individually, deeper players are of course better. What does the average value of each central triangle tell us?

Now it gets really interesting. Bayern are No. 1, No. 2 is the BVB, Schalke and Eintracht follow. The positioning of the last two (generally known for their pressing and tackling) behind the “team in crisis” Schalke and the more aggressive and open Eintracht is relatively easy to explain.

Freiburg uses pressing high up the pitch against the opponent’s build-up play. When pressing after an opponent’s pass, the wingers are often successful on the sides, resulting in Freiburg’s slight drop in pressing competence compared to Schalke and Frankfurt.

Mainz relies much on counter-pressing (and thus on the collective) and on the sheer quantity of tackles. At the same time, they have three Sixes and Ivanschitz for help, probably resulting in a dropping rate. In contrast, at Schalke Holtby, Jones and Neustadter work very hard especially where runs are concerned; on the other hand, this is probably not a particular strength of Afellay, Farfan and Draxler.

Dortmund in second place behind Bayern fits well – without much of a doubt these two teams have the strongest midfielders in the league, from a defensive point of view as well.

Anything else?

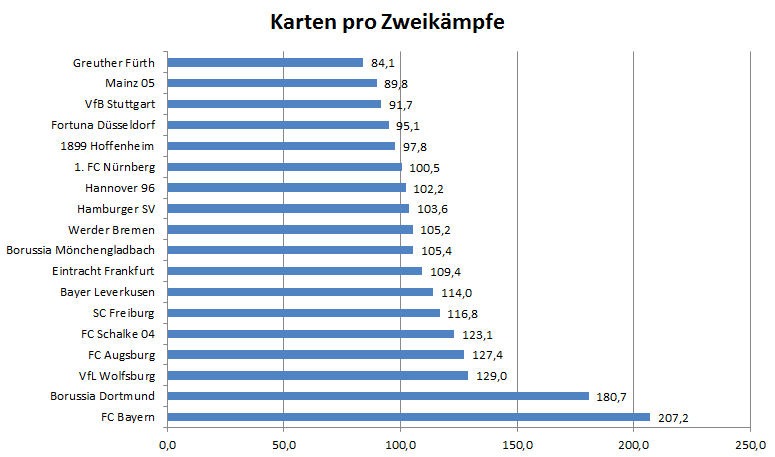

After this seemingly enormous effort, I wondered whether it’s possible to measure intelligence and strength in the game against the ball in a different way. Then I thought of something I had scribbled down somewhere: “Use booking stats!”

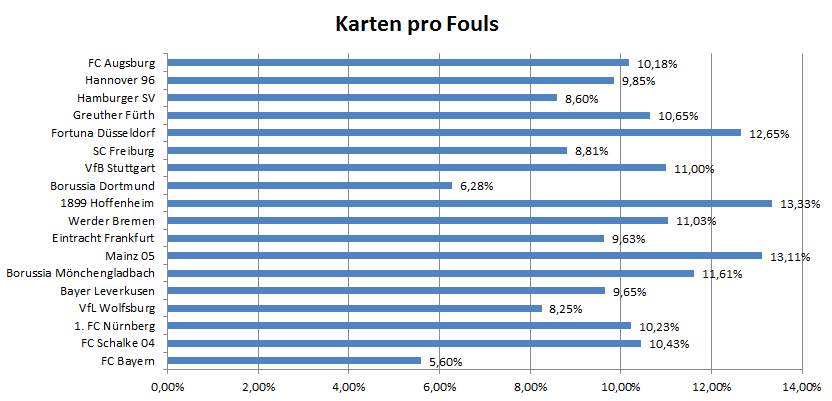

Those who press well should get booked relatively less. Ball possession may influence that, but this is why I put the number of bookings received after fouls in relation to the team’s tackles (which should also be influenced by ball possession).

As the numbers are in extrem favour of the Top2, it is probably not a very significant statistic, but it agrees remarkably well with my opinion and the defensive competence statistics above.

The Bavarians “need” 200 tackles to get booked. Yeah, I know, the Bavarians and the referees … ok. Thank God Dortmund excels here as well, otherwise I could not fight conspiracy theories with a tactical explanation. The gap after those two seems particularly significant.

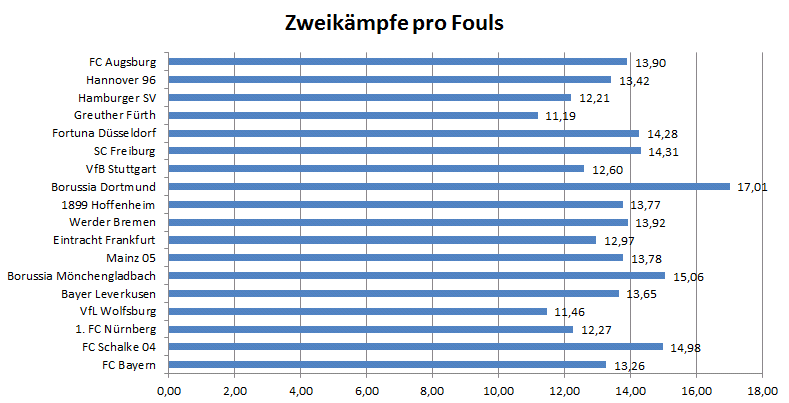

But are these really the best stats? Perhaps we should rather measure tackles per fouls. There we go:

Here, Bayern are below while Dortmund is above. This could possibly be due to the increased use of tactical fouls. In absolute numbers they probably have slightly less defensive tackles and more offensive tackles with the ball.

Let’s therefore have a look at additional stats that might clarify things further:

Where bookings per fouls are concerned, Bayern and Dortmund are again clearly ahead. Only 5.6% of Bavarian fouls resulted in a booking. Due to their intelligent tactical fouls and their effectiveness Heynckes tells them to play that way, which explains the mediocre statistics of tackles per fouls.

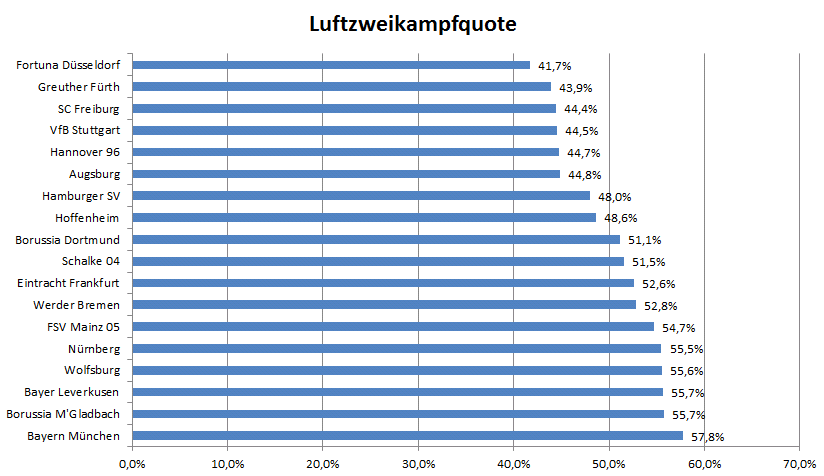

Finally, we will have a look at an underestimated quality of Munich. In the Champions League, they have so far won 67% of their aerial duels. All across Europe, they are on top in this regard. It is similar in the league:

With 57.8% the Rekordmeister is the undisputed leader. It is another effect of the central defenders and of collective play. I would love to set this in relation to pressing and possession, but even though Tony Pulis at Stoke City strives to introduce aerial pressing, I still do not see the point – which is why I hereby bring the analysis to an end.

I just presented 30 graphs, more than 6000 words (15 .doc pages without pictures!), statistics, game scenes and general observations. What else could you expect – besides better language, structure and competence? Of course: a conclusion.

Conclusion

Bayern’s play against the ball has clearly improved this season. The counter-pressing is partially executed perfectly, the team seems to be more balanced, communication is right, and the signings of recent years seem to be paying off.

Contrary to the opinion of the yellow press Javi Martinez’ (defensive) performance seems to pay off as well. The Bavarians have set course for the championship and a new record in terms of goals conceded – not just because of their individual class, but due to a strong collectivity in defensive play. Whether they succeed depends on what template they will use.

Will their template be the excellent initial phase, or the somewhat sluggish phase after that? I personally liked the Supercup match against Borussia Dortmund – you can watch the game in full on YouTube. As early as back then you can already recognize the pressing, which ultimately results in a very flexible way of playing. Thus, they create a basic framework for offensive fluidity and stable possession football.

In reference to Bayern’s pressing play I quote in closing the most competent person I know regarding football tactics:

“Their ability to generate positions – awesome.” – Tim Rieke (TR)

Written by RM, translated by PF

15 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Kari November 14, 2013 um 9:20 am

“Klopp’s invention” Barcelona have used this type of pressing for years so where is Klopp’s invention here? Is there really anything new?

Derkyi @derkyifcb March 10, 2013 um 9:42 pm

This site is very beneficial to me and my Ghanaian friends. I hope this great club becomes popular again in Ghana and Africa. Auf geht’s Bundesliga

mb March 9, 2013 um 5:22 pm

DMÜLLER. The D is silent

mb March 8, 2013 um 10:00 pm

Great idea to translate this particular article! I remember it being exceptionally good, and on this site that says a lot.

Bayerns pressing and specifically their counterpressing, as described here, are miles ahead of last season. The players actually organize themselves efficiently immediately after losing the ball, instead having one or maybe two players randomly pressing and the others just watching. Heynckes did tremendous work! And Martinez is an impressive player that has already become absolutely central to bayerns play, in the defensive and offensive stages.

On another note: MÜLLER UNCHAINED! That’s an instant classic 🙂

Rooney>vanpersie March 8, 2013 um 7:43 pm

Would you suppose martinez’ passing (short, long, through balls) and dribbling skills to be superior to gustavo’s? I think the brazilian is slightly more dynamic near the opponent’s box

Nr.39 March 8, 2013 um 7:07 pm

Didnt read lol

FL (aka LeFlo777) March 8, 2013 um 6:27 pm

bevor ich den text jetzt durchackere: gibt’s dazu ein deutsches Pendant? Wäre vielleicht schön, wenn ihr ggfs jeweils die deutsche und die englische Version miteinander verlinken würdet.

RV March 8, 2013 um 6:11 pm

Da ich selbst Englisch studiere, weiß ich, wie schwer eine vernünftige Übersetzung ist, besonders bei einem Text, der nur so vor Fachbegriffen strotzt. Nach dem Überfliegen muss ich jedoch sagen, dass es in den meisten Fäll es auch gut gelungen ist, einige kleinere Fehler habe sich meines Erachtens aber eingeschlichen. Auch bin ich auf einige Germanisms gestoßen, bei denen ich aber auch erst etwas überlegen müsste, ob mir da überhaupt eine bessere Lösung einfällt.

BVB3000 March 8, 2013 um 6:05 pm

Very impressed by Bayern this season. Heynckes has introduced an effective balance between attack and defence that is reflected in your statistics. Scoring was never a problem even under Van Gaal but keeping goals out was another matter. Bayern were suspect defensively, but not this season. There is a lot more movement all over the pitch, a lot more PRESSING when the opposition have the ball. They defend well and they can hit teams on the counter. Can’t wait to see the return of the king (Guardiola), expect to see “Mueller Unchained” next season :()