UEFA Supercup: Bayern Munich – Chelsea 2:2 (5:4 Penalties)

Chelsea and Bayern Munich faced each other in the European Supercup Final. Before the match, both managers emphasized that the match was about the teams, not themselves. That is true, of course; still, fans of tactics like us are interested in both teams and managers, especially in a match-up of two managers that are considered to be the best in football tactics– even if we disregard their previous common history. And the game lived up to the expectations, if in a somewhat crazy manner.

Chelsea, game rhythm and counter-play

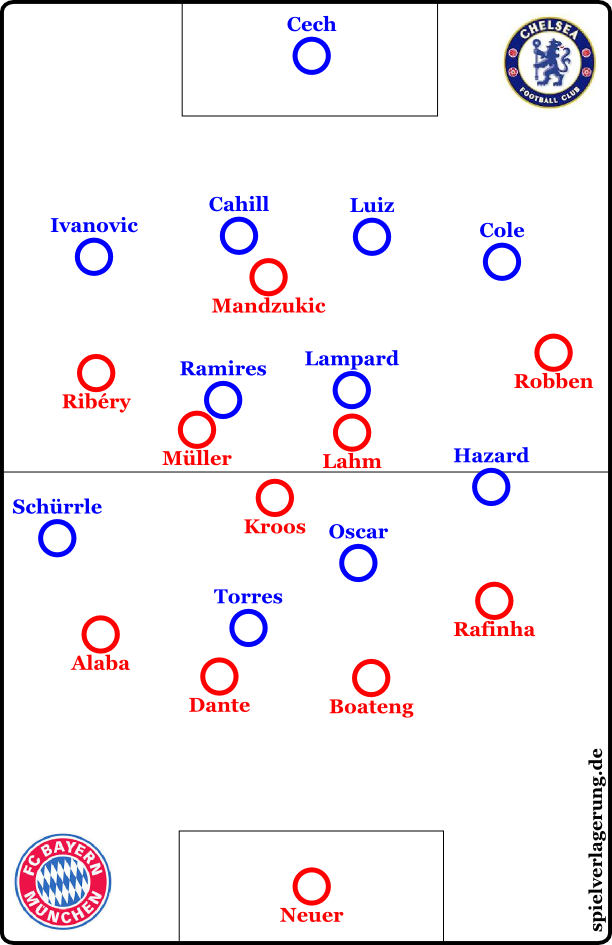

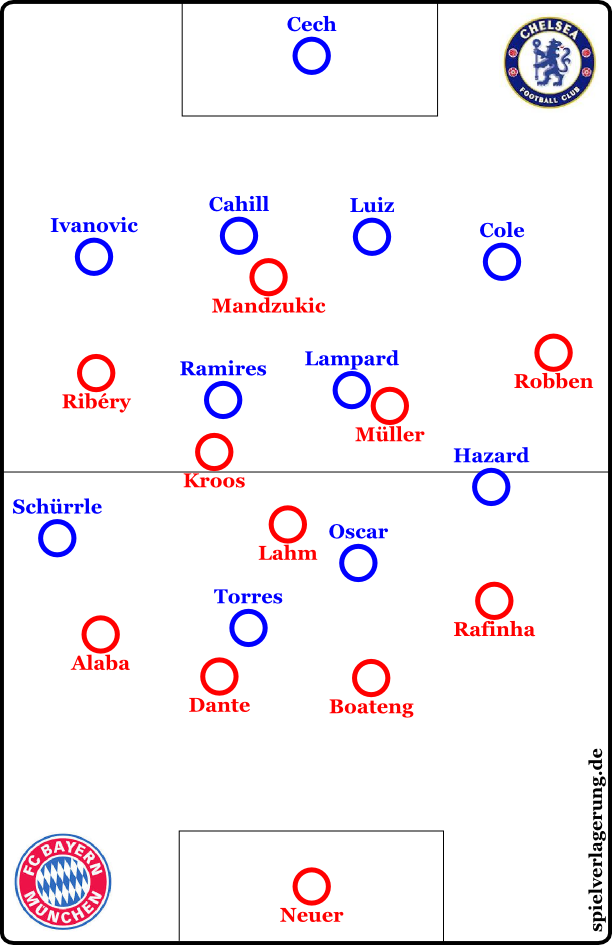

Some might have felt reminded of the Champions League Finale 2012: Chelsea was on the defensive and let Bayern keep the ball. Bayern subsequently had some attempts on goal but wasn’t very dangerous (41 attempts, “only” 10 on target). Still, there were some differences. Chelsea counter-attacked significantly more often and organised their defensive higher up than they had two years ago. In pressing, they mostly employed a 4-4-1-1/4-4-2 (sometimes using the wingers a bit higher up) with Oscar usually supporting Torres up front; later he fell back and employed backward pressing situatively in midfield around the six-yard-box.

This form of pressing mainly started in their own half – rather passively so – and increased in intensity around the box: classic Chelsea, in a way. The English defended their box very well. In some situations, the Blues nevertheless pressed extremely aggressively and high up the pitch. They started by isolating the opponent and then narrowed space on the side to employ sudden pressing locally – similar to Mourinho’s style when he was managing Real.

If they succeeded and got the ball (mostly in their own half of the pitch) they moved forward fast. The structure of the attacks was clearly visible: Hazard and Schürrle remained out wide, Hazard trading positions with Oscar now and then. Schürrle was the open man of choice, letting Hazard and Oscar charge down the centre. Torres played as a swerving centre forward and opened up space. Counter-attacking with only four players might have resulted in short-handed attacks – but balls won deep and extremely fast transition play resulted in even numbers (also due to the speed and the technical prowess of Chelesa’s attacking three). Oscar’s and especially Hazard’s pressing resistance helped to retain the ball in close quarters and to advance the counter-attack. The holding midfielders and fullbacks remained deep on the offensive, keeping Munich’s counter-attacking chances low. Chelsea stuck to the formation and remained compact.

Bayern had some attempts on goal as well – still, their possession play seemed at times a bit unstable, both in offense and defensive.

Bayern: dangerous in the wrong places

At halftime, Guardiola and his “new” Bayern team were criticized in forums and on twitter. Still, Munich showed some good structure and at times an improved coordination in offensive combination play. There were some interesting tactical group movements that were working well and created synergy. Still, those tended to open „wrong“ space. They gained space on the wings and down deep rather than in the centre and in half-space between the lines.

Let’s take a look at these movements:

- Müller pushed out up front while Mandzukic moved into interfaces on the wings.

- Mandzukic sometimes moved to the right turning into a winger, freeing Robben.

- Mandzukic sometimes moved to the left (if not that wide than he did on the right) to open up space for Ribéry and Müller in the centre.

- Bayern often employed a 2-1-3-4 with a 4-1-1-3-1 role allocation, as the full-backs did not just use space along the lines but also diagonally moved inwards into open half-space in midfield to offer themselves as open men.

This opened up the sides and should have helped the wide wingers, if Chelsea had not defended in an unexpected way. The Bavarian wingers were not aggressively covered by two or even three opponents, and there was no extremely deep positioning and man-marking, but rather a passive style of play with lots of shifting, situative man-marking, and a position-oriented performance.

Thus, the movements mentioned above were limiting rather than they were helping to open space for the wingers or to occupy the centre to enable through balls. They opened space, and Ribéry got off a couple of shots. But these positions were too far out on the side, and the shots either missed the goal or were easy prey for Cech. Bayern’s first goal was due to Kroos who gave Ribéry some freedom in the centre, resulting in an unimpeded shot from a good angle. This movement was nowhere to be seen in the first half.

Still, Guardiola took care of these problems earlier than that, switching Kroos’ and Lahm’s positions after the 0:1. Lahm was moved back, pushing the Kroos to the centre.

Bayern improve after half-time

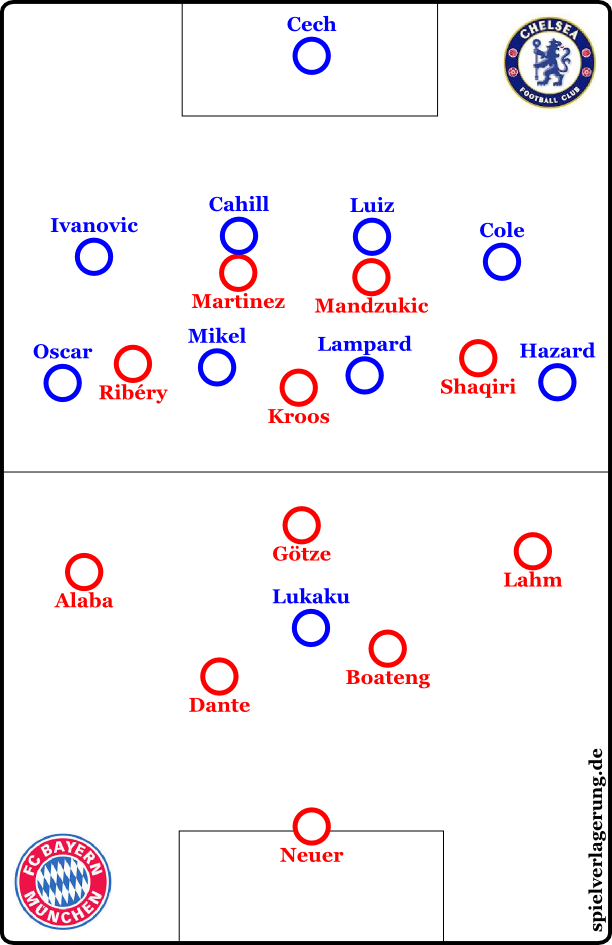

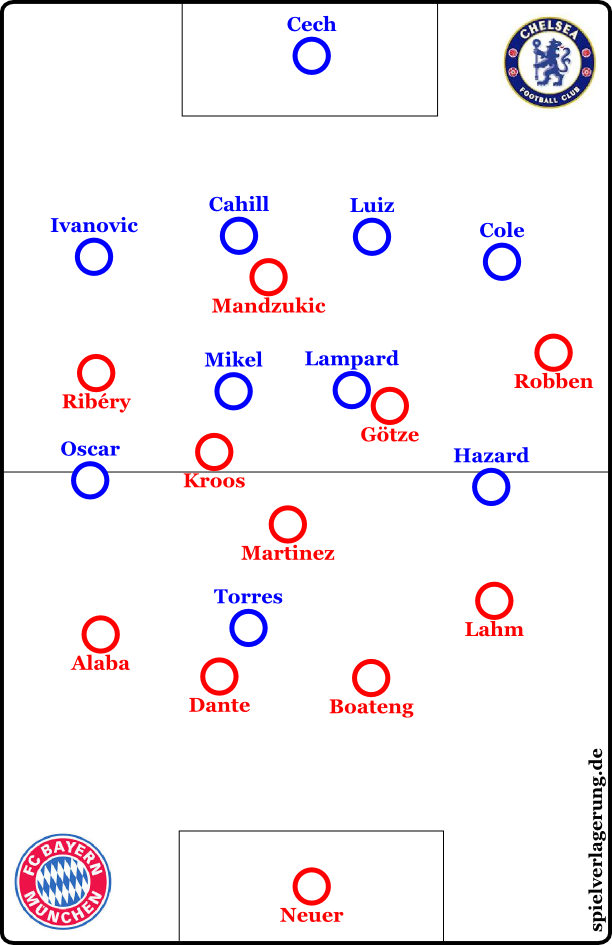

Other changes helped Munich to improve (tactically) after halftime. Counter-pressing became more aggressive and intense, and the offensive structure was modified a bit as well. Positions were generally more freely interpreted. Robben moved in from the right to the centre more often, even without Mandzukic. The latter moved closer to the line when he swerved to the left, and he tended to remain in this „new“ position for longer periods. Kroos and Müller traded places in tune to this (if in a flexible manner).

Guardiola later subbed in players more suitable for these modifications. Javi Martinez came in for Rafinha, letting Lahm take up Rafinha’s position (promptly interpreting this role higher up the pitch and with more intelligence). Rafinha often lacked balance when he had to decide whether to play diagonally or vertically. Especially his vertical movement showed problems in timing, and he did not venture out far. Lahm found himself playing on his favourite position: he plays well as a single Six, but it does not come as naturally to him as the role as a Nadel- and/or Balancespieler further up. Martinez was better suited to this position and to this more aggressive style of pressing, Kroos was well supported, and Müller could push out to the right wing and to the front with more aggression.

Martinez tilted a bit backwards – and, as usual, intelligently so: if necessary against a 4-4-1-1/4-4-2. Apart from that, he moved back and forth between the half-spaces or created a triangle with the centre-backs. His pressing resistance and good ball distribution were convincing in spite of his technique that seemed a bit erratic. Müller failed to consistently impress in midfield (though he made some good passes) and was replaced by Götze, a midfielder and potential Nadelspieler, and an alternative for the centre-forward position should Mandzukic swerve aside.

How did Mourinho react? He hardly did at all. The rhythm disruptions became less frequent. After Munich equalised the Blues played up higher and moved the game more to midfield, forcing Bayern to switch sides more often. Apart from that nothing much happened. After the send-off Mourinho substituted Schürrle with Obi Mikel to keep two banks of four with a double pivot in front of the defensive.

Extension

Still, the assumed decision wasn’t far away – in Chelsea’s favour. Bayern tried to press higher up in extension time, but Chelsea pushed out and managed to get a long ball by David Luiz to winger Hazard who moved past Lahm and Boateng Gambetta-style.

After that, Bayern tried it all: Robben was replaced by Shaqiri and joined Kroos in the centre as an additional option for a hard long shot. Götze and Ribéry acted as „false wingers“, playing sometimes wide, interacting dynamically with the fullbacks, moving to the centre afterwards – they created attacks and chances, but no equaliser.

But the changes kept coming. Bayern refrained from providing width when attacking in the last third – in order to add to central presence for short passing combinations – but without success. Later, Götze acted as deep-lying playmaker (with Boateng moving up, just as Lahm did situatively from the side), Martinez moved up front teaming up with Mandzukic as striker. Bayern concentrated on crosses in the last minutes, yielding success in the last minute: Martinez profited clinically from a cross out of half-space. I won’t comment on the penalties. Except for this: Did Manuel Neuer choose the right corner on purpose, four times in a row? Just to jump left on the fifth attempt?

End of the game, much fluidity on the wings, Boateng pushing forward – and Manuel Neuer just behind.

Conclusion

The game featured various phases: in the beginning, the teams were equals, Chelsea probably a bit more dangerous. Still, Bayern started to hit back in the first half. They dominated in the second half especially. Paradoxically, this seemed to change with Ramires’ send-off. Chelsea used Bayern’s more offensive play and changed rhythm to succeed in a tactically simplified situation. They employed ten players in a 4-4-1/4-5-0 to nearly decide the game – but Bayern turned the game around, using good old plan B (consisting of three Bs: Brechstange (crowbar), Bewegung (movement) und Bullen im Sturm (bulls as strikers)) to equalise – and won on penalties.

If you enjoy a shortcut just take a look at this short analysis of Guardiola’s tactical plans by a user of transfermarkt.de and Bayern fan (here). It’s eloquent, short, compact. I’d like to praise a stranger who is probably part of our community!

Written by RM, translated by PF.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

messanger September 4, 2013 um 4:52 pm

I’ll post this here instead of the German article.

Re: Neuer’s penalty movements

I believe he had jump to the left (Penalty/TV Viewers POV) in the first 4. David Luiz and Lampard are right footed and known to shoot hard. Both used the same kind of technique: no hold back (Verzögerung), as hard as possible in one angle. Neuer can decide to try to save the obvious one (the way they actually converted) but in order to save a shots like these he probably needs both hands/fists and needs to jump early.

So he jumps to the left side. Why? If Lampard/Luiz turn their foot around in the last second, their shots will be weaker and less precise which leads to a better chance for a save for Neuer.

Lukaku shot with his left foot (if I remember correctly), Neuer jumped to the right (Again shooter/viewer’s POV) which is the weaker side. Also Lukaku didn’t really have a Poker Face/Walk.

Ewin Harbauer September 2, 2013 um 4:36 pm

Dear RM,

I really appreciated your analysis.

Regards

Erwin