Germany – Argentina 1:0 (aet)

Germany win the World Cup! In a dramatic match the DFB team best Argentina 1:0 after extra time. RM, TR, MR and CE had a look at the game and saw a tactically diverse battle of rhythm…

Basic Strategy

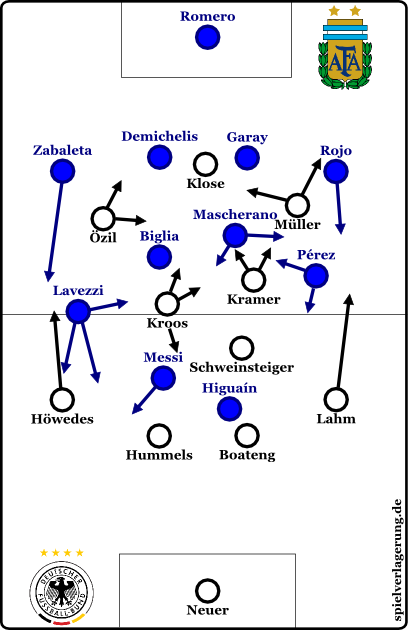

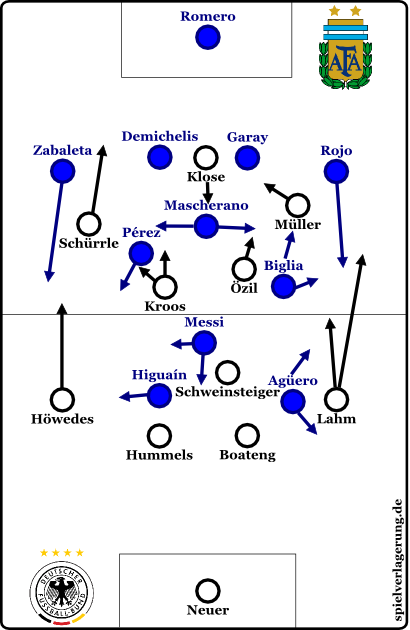

Both teams did not intend to change their personnel compared to the semi-final matches, but Sami Khedira had to bow out minutes before the start of the game. Christoph Kramer replaced him in midfield. As for the whole World Cup, Joachim Löw relied on a particular variant of the 4-3-3, in which details were slightly adapted to the respective opponent. Most importantly, play on the right side, where Kramer took on an important role, was slightly stretched in the beginning.

Löw’s counterpart Alejandro Sabella could not field Ángel di María, so Enzo Pérez stayed in the team. However, the Benfica player began on the left side and Ezequiel Lavezzi on the right. Sabella stayed with 4-4-1-1 and the free role of Lionel Messi behind the horizontally agile Gonzalo Higuaín.

German Build-up

Argentina started with thoroughly surprising pressing stabs, with Higuaín chasing aggressively and trying to isolate the central defenders, while the wide players pushed up depending on the situation. The remaining collective was man-orientated now and then and Messi positioned himself away from the ball. Germany were able to free themselves fairly easily via their midfield players, notably Schweinsteiger, because of the individual nature of the pressing. Nevertheless this created an unpleasant, irregular rhythm which affected further attacking play negatively. Because of this, play against the Argentine midfield bank was too hectic in the first half.

Most notably, in the context of light man-orientation Biglia pushed up towards Toni Kroos, covered by Mascherano, who was in behind and positioned slightly diagonally. Both nominal wide players also positioned themselves diagonally and stayed close to their two colleagues, closed down possible runs around them and secured the center. Germany had a difficult time breaking this line down in possession, which they dominated. There were indeed gaps now and then between Argentina’s banks, but because of the tight and staggered player distribution the Germans were anxious and clumsy in these areas.

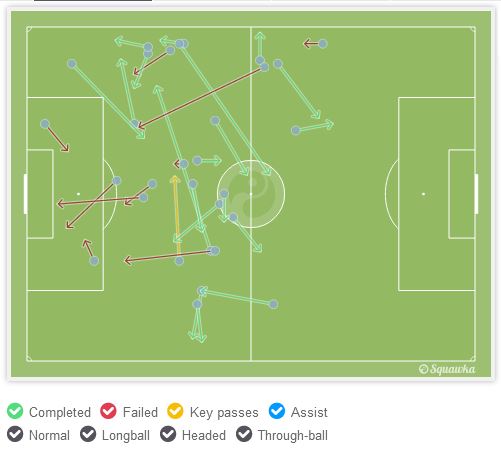

Schweinsteiger and Kroos, who found himself in acres of space, because Höwedes advanced further than usual and pushed Lavezzi back, initiated attacking play, characterized by a good approach and problems in realizing the plan. Germany played mostly down their right side in the final third, because Müller was very active and switched positions with Klose and Kramer, the more advanced eight, while Özil drifted long distances into the center. In doing so they approached the last bank diagonally, and did it well a number of times, promising dynamics developed around Müller and Kramer. Mostly one of the attacking players – frequently it was Kramer – was evading and opened the pass towards the center. Klose and Müller were able to let balls bounce there and, depending on the situation, an additional player joined them. These demanding plays, made more difficult by defenders expertly advancing, were not at all easy to finish given the lack of space and direct proximity of the penalty area and so many plays collapsed close to the breakthrough.

The forced substitution of Kramer was another reason the German team only managed three finishes before half-time. Schürrle added his attacking potential on an individual level, but the structures changed as well. After a short period with Özil as eight they employed a slightly stretched 4-2-3-1. Diagonal synergies were lacking in the right attacking half-space with Özil as ten and the new man on the left, because the positions were being interpreted more strictly. In addition, player distribution in attack, so convincing in the beginning, weakened. Changing formation was not the only reason for this, instead it was a general, gradual development. The Argentinians were now able to open the space between the lines and push up their bank of midfielders for short spells. Before the half-time whistle Germany let themselves be guided towards the wing more frequently and more easily, so that attacks on the right wing tended to end in crosses from deep or rather predictable combinations by Müller and Lahm. This worked out OK, because of the persistent attacking presence, one example being the situation leading to the corner where Höwedes hit the post.

Argentina’s Defensive Rhythm

Fundamentally the German team played very well. Player distribution in attack was good over long periods of the first half, plays were well covered and there was still a lot of control in the final third. Add to that intelligent circulation and strong dominance in midfield. In a few moments they still had to struggle: they let themselves be guided into unpleasant structures, a few balls were lost in front of the final third and there were many strategically inefficient attempts at goal despite their promising basic formation. The reason was the particular, destructive rhythm, which the Argentinians had almost perfected as the knockout stage progressed.

Basically they lined up in a 4-4-1-1-/4-4-2. They sat deep, stayed passive during long phases of circulation by the Germans and had problems keeping their formation compact. Frequently there there was a relative lack of compactness horizontally, where half-space was unoccupied or occupied in a structurally unsound way, for instance. As usual the distance between midfield and attack was great, while the distance between defense and midfield was extremely short to lock Germany out of the space between the lines.

In their uneven compactness Argentina still seemed interesting, aggressively threatening and, paradoxically, compact. They employed a lot of situational man-orientations, within those they were focusing on the center and closed open pockets of space dynamically and extremely aggressively. Javier Mascherano and Lucas Biglia pushed up frequently and attacked the German midfielders. Because of the long distances they rarely got control, but they did push Germany to the flanks and then fell back.

The Argentinian wingers and fullbacks reacted accordingly and pushed up aggressively, in some instances Lavezzi even ran at the German central defender in suitable backwards-pass moments. Other than that they stayed deep and wide and were only waiting for the guiding actions of the central players. The rather passively shifting forwards had their explosive part in the change of dynamics when they finally did react. The wide players withdrew far into the middle if the guiding elements were not triggered because Argentina were being outplayed or Germany had gone diagonally into open half-space.

These situations were marked by an emerging and extreme horizontal density partnered with a reactionary drive, which sped up the German combinations in the second third of the pitch to an unpleasant degree. Because of these movements clean shifts of play to the flanks were sometimes barely possible. The forward runs of the German fullbacks had been partially stopped by the prior wide positioning of Argentina. Höwedes’s attitude, defensive by default, became the expected problem for the German team. In the center there were extremely dense 4-4 formations near the box. Eight players moved in unison and actively covered towards the ball and Germany lost possession numerous times as they tried to combine through the tiny spaces in between. Otherwise they passed backwards (many crosses from deep incoming) or pressed into sub-optimal position for finishing around the box.

Argentinian Build-up and Structures in Attack

That the Albiceleste would not go for long passing circulation and trust in a simple structure instead was to be expected even before the match. Especially in the first half, this was the course the game took. First priority was including Messi. Either the captain was sent on tempo dribbles down the right flank, like Lavezzi, or the 27 year old was sought out in the center. Messi drew one of the three German central players with himself and was able to free himself or open space before passing to a teammate.

Argentina went for their customary overloading on the right. During the first half they mostly relied on Lavezzi and his linear, quick runs. Curiously Höwedes had drifted narrow a number of times, leaving the flank partially open, which resulted in space for runs. In these moments Messi even stayed away from the ball on purpose while Lavezzi and Zabaleta simply focused on breaking right through.

That they were able to shift play to this side at all – despite the strong German pressing – was definitely a result of the unorthodox defensive rhythm, which allowed them to win possession in isolated, uncrowded space or in situation where they had superiority of numbers. In both cases Germany did not have immediate control through counter-pressing, even if Kramer tried to establish control as quickly as possible, especially early on. Lavezzi has able to directly speed up for his dribblings for example, or they freed themselves with a shift to the right side. On occasion Messi could receive the ball in loose situations, which caused Germany the biggest problems.

Another approach to breaking were long balls against the high German back line. On occasion runs started directly at the edge of offside and a long ball came from the advanced defensive midfield. Some passes were played expertly, that they did not reach Neuer’s area of control before an Argentinian could pick up the ball. Still, in some way Germany were always able to get behind the ball, at the latest in their box, and repair the damage with their customary, strong defense if need be.

Argentina’s Change of Formation after Half-Time

Sabella changed his formation right after the break. Our colleague MR had mentioned in our preview that a diamond formation, namely a 4-3-1-2, could be an unpleasant way to play against the German national team. Argentina employed this formation in many matches during qualification and had been interpreting it suitably asymmetric. Di Maria on the left played higher up the pitch than Gago on the right, resulting in 4-2-2-2 and 4-2-3-1 formations in attack. Against possession they changed to a 4-3-1-2 or a 4-3-3-0 with withdrawn forwards.

Even without di Maria and Gago they basically played the same way after the break with the introduction of Agüero for Lavezzi. Pérez did not play as wide and drifting in attack as di Maria, so that their attacks were more focus on the center and better covered for. Agüero and Higuaín acted as space-openers and combination partners for Messi, with Agüero drifting more. Messi alternated between a free role in midfield – frequently he could be found right in front of defensive midfield – and a part as deep-lying forward drifting towards the right. Pérez advanced with dynamic, intelligent runs on occasion or was a free, pressing-resistant passing station further back.

At first Agüero man-marked Schweinsteiger while Higuaín directed play towards the right flank and away from Toni Kroos. Germany had to build via the flanks a lot and was rarely able to involve their two strong defensive midfielders with any sort of effect. If Germany managed to advance and play across a larger area in the final third, Argentina relied on the effective 4-3 formation in front of the box. The active and partially man-based movements of the defenders were compensated by the eights, who sat in the gaps. Defensively this was a stable and gritty mix.

On occasion Germany was able to find channels on the side, but Schürrle and Müller often found themselves in difficult, isolated positions, which the were unable to solve cleanly to play on. The big problem in attack for Germany in this second half was that they let themselves be pushed to and trapped at the sidelines too easily by the Argentinian formation and their occasional guiding elements. Argentina succeeded because their 4-3-1-2 formation frequently became a 4-3-3-0 with withdrawn forwards, whose covering cones locked down central midfield even more and whose narrow horizontal positioning guided German build-up to the flanks. At times the Germans clumped on the wing with fullback, midfielder and winger, a situation that could not be broken up by the forward surge of the attacking players on the other side of the field.

The slight asymmetry of both Argentinian banks behind the deep forwards was interesting. Midfield was slightly shifted towards Lahm, the left outside player clung aggressively to Lahm. On the other side Zabaleta pushed towards Höwedes or Höwedes was attacked half-heartedly by the right outside player of the diamond. The bank of three shifted towards the ball intensively while the bank of four behind them was much more focused on the center and their shifting was less pronounced. Germany reacted with bigger vertical gaps and a stronger involvement of the wings, where the right wing was clearly being preferred at first.

Pérez even switched from left to right, because he is more dynamic than Biglia and better able to use open space after lateral shifts. Later the fresh Gago replaced the tired Benfica star. In addition there was another substition by Sabella: Rodrigo Palacio replaced Higuaín. Both contributed different movement patterns to the match, but the basics remained the same. Breakthroughs focused on the center, Messi-focus with drifts to the right and backwards, constant high cover and more presence through more attacking options as well as the positive side-effects when out of possession.

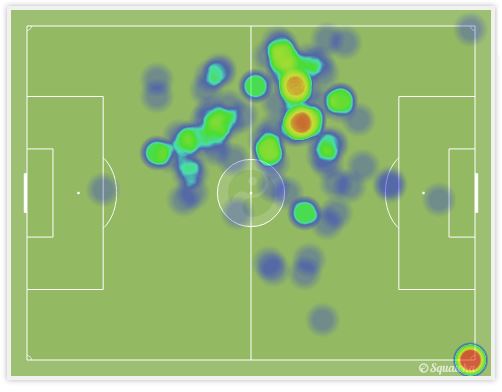

Heatmap Toni Kroos – Quelle: Squawka

At first Agüero man-marked Schweinsteiger while Higuaín directed play towards the right flank and away from Toni Kroos. Germany had to build via the flanks a lot and was rarely able to involve their two strong defensive midfielders with any sort of effect. If Germany managed to advance and play across a larger area in the final third, Argentina relied on the effective 4-3 formation in front of the box. The active and partially man-based movements of the defenders were compensated by the eights, who sat in the gaps. Defensively this was a stable and gritty mix.

On occasion Germany was able to find channels on the side, but Schürrle and Müller often found themselves in difficult, isolated positions, which the were unable to solve cleanly to play on. The big problem in attack for Germany in this second half was that they let themselves be pushed to and trapped at the sidelines too easily by the Argentinian formation and their occasional guiding elements. Argentina succeeded because their 4-3-1-2 formation frequently became a 4-3-3-0 with withdrawn forwards, whose covering cones locked down central midfield even more and whose narrow horizontal positioning guided German build-up to the flanks. At times the Germans clumped on the wing with fullback, midfielder and winger, a situation that could not be broken up by the forward surge of the attacking players on the other side of the field.

The slight asymmetry of both Argentinian banks behind the deep forwards was interesting. Midfield was slightly shifted towards Lahm, the left outside player clung aggressively to Lahm. On the other side Zabaleta pushed towards Höwedes or Höwedes was attacked half-heartedly by the right outside player of the diamond. The bank of three shifted towards the ball intensively while the bank of four behind them was much more focused on the center and their shifting was less pronounced. Germany reacted with bigger vertical gaps and a stronger involvement of the wings, where the right wing was clearly being preferred at first.

Pérez even switched from left to right, because he is more dynamic than Biglia and better able to use open space after lateral shifts. Later the fresh Gago replaced the tired Benfica star. In addition there was another substition by Sabella: Rodrigo Palacio replaced Higuaín. Both contributed different movement patterns to the match, but the basics remained the same. Breakthroughs focused on the center, Messi-focus with drifts to the right and backwards, constant high cover and more presence through more attacking options as well as the positive side-effects when out of possession.

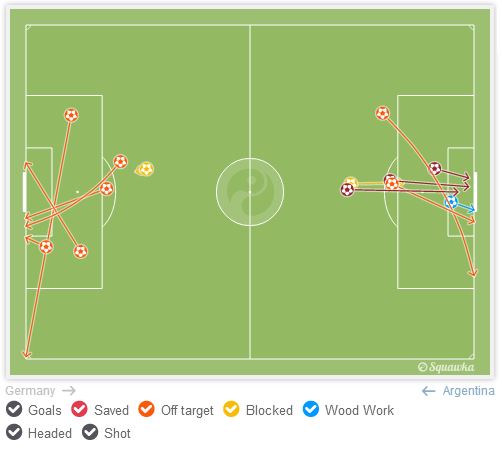

Shots – Source: Squawka

The Final Period

There were only small tactical and strategic changes in extra time, but they showed clearly in game rhyth and events. Philipp Lahm argued after the game that they had simply had “more energy” left and this is probably the best way to describe it. In the end the victorious team had run 10 kilometres more. Germany played very high up the pitch, attacked aggressively and tried to force a decision in extra time, while the Argentinians did the opposite. They withdrew, dropped deeper than ever and concentrated on the lucky counter-punch.

There were a few dangerous situations and potential break-throughs, but all in all Germany defended excellently. Counterpressing worked well, was stable and the ball circulation in attack pushed the Argentinians back even further. Especially impressive were Boateng’s forward pushes, he frequently and aggressively moved into the space between the lines and clamped down well on breaks, but the evenness of movement by the fullbacks and in midfield was convincing was well.

In addition the Germans found back to the old rhythm with the larger central space and greater possibilities for lateral shifts, while the Argentinians increasingly abandoned horizontal density, clarity of formation and cutting off open space, resulting in a weakened defensive presence. Götze as center forward was able to hone in on those problems with his drifting. Before his decisive goal he himself created the space for Schürrle’s dribbling along the side-line by drifting left and drawing Zabaleta decisively towards the middle “on the way back.” After that Argentina kicked the ball around to force an equalizer, but Germany remained stable.

Conclusion

This final was in many ways more even than could have been expected. During the first half Argentina tried to surprise the high German line with Messi and long, direct balls. During the second half Sabella adapted his team and the diamond destroyed the German game for the time being.

The new champions had to claw back with small changes and a slightly different way of playing. Towards the end of regulation the final was dominated by the fear of failing. In the end Schürrle broke through on the left once and set up a free Götze in the penatly area. The basis for success was defensive stability, despite all the work: Neuer did not have to make a single save.

Germany now has the fourth title, the fourth star. Lahm’s generation rewards itself with the greatest of all titles in football on the final stretch of their career. For Hummels, Müller, Götze and others it can be but a prelude.

In the end it was also a victory of flat hierarchies, modern player types, system-footballers, collectivity, tactics, intelligent football, modern goalkeeping and the German academy system. And: a victory of Joachim Löw.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen