U21 European Championship Final: English Manipulation of the German Pressing – MH

England wins the U21 European Championship final against Germany 3-2. After just 20 minutes, England leads 2-0. This aspect analysis focuses on the reasons behind the German attacking press’s lack of access to England’s build-up play.

The U21 European Championship final offered several interesting tactical elements. This analysis focuses on Germany’s lack of access in their attacking pressing and marking. Particularly in the first half, England repeatedly managed to bypass the German press, often gaining large amounts of space in the final third, which led to dangerous scoring opportunities.

The early deficit also contributed to Germany being unable to focus, as they usually do, on securing depth in their pressing. Instead, they were forced to put direct pressure on the ball carrier in order to force turnovers. After the equalizer to make it 2-2, Germany noticeably pressed high less frequently. Therefore, this analysis examines Germany’s pressing and marking, as well as England’s build-up play, up to the 60th minute.

Closing down during goal kicks

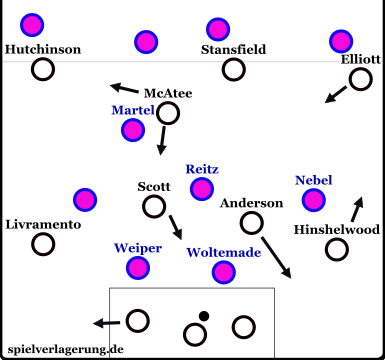

One of the trends at the U21 European Championship was that many teams aimed to press the opponent’s goal kicks with a +1 player on the last line or in the space between the lines just in front of the back line. Many teams—including Germany—used man-oriented marking when closing down during goal kicks.

Since most teams build up from a 1-4-2-4 structure on goal kicks, it is equally common to press man-to-man from a 4-1-3-2 shape, with the two holding midfielders (the “sixes”) staggered vertically.

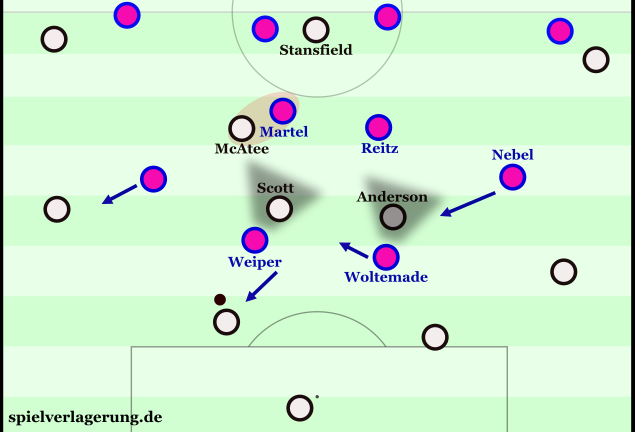

The deeper-lying holding midfielder (for Germany: Martel) acts as the +1 player, positioning himself in space based on the location of the ball. When the opponent plays through the space between the lines, he can create a numerical advantage there. In the final third, pressing is carried out against a 1-4-2 build-up using a 3-2 shape. The more advanced holding midfielder (for Germany: Reitz) typically positions himself centrally and marks the ball-near holding midfielder, while the far-side winger presses the ball-far holding midfielder.

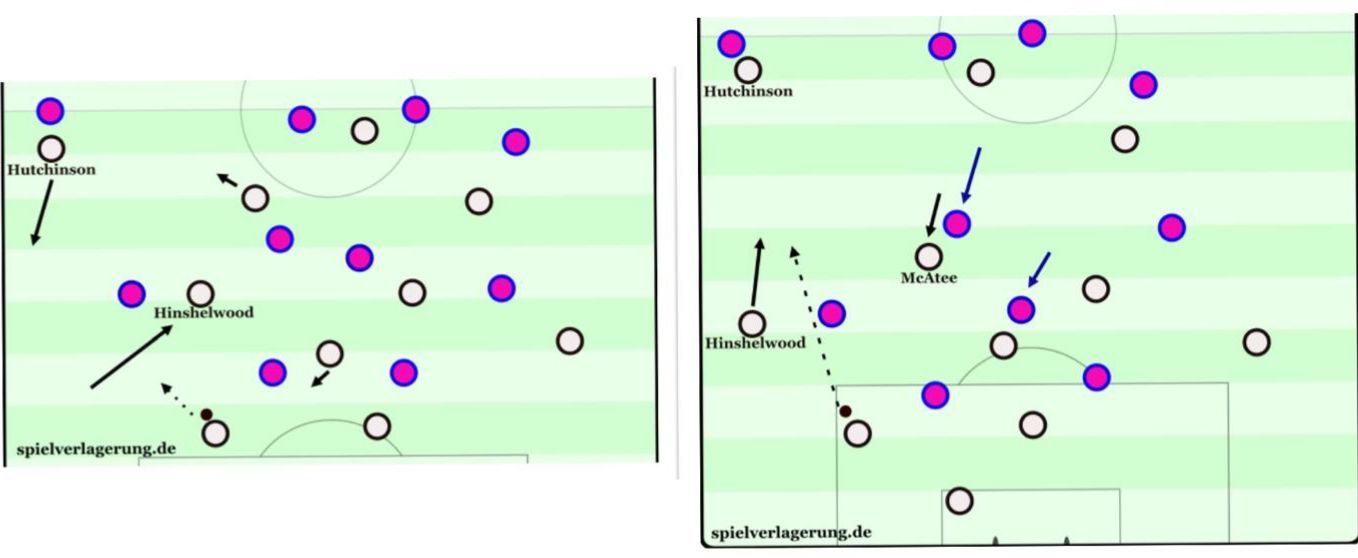

The English side, by contrast, caused problems for the German team’s marking assignments through an asymmetrical structure. As a result, England had several options for exploiting their numerical superiority in the build-up without having to immediately play into the space between the lines.

What remained consistent was the intention to establish central possession in front of the first pressing line using different players, in order to build up play on either side. Central possession makes it more difficult for the pressing team to steer the play in a specific direction, as the passing angles from central areas are wider than those from more advanced or wider positions.

Central possession complicates the opponent’s shaping of play. Anderson’s drop frees him from Woltemade’s marking shadow and creates a numerical advantage against Nebel, who must now cover both the advanced full-back and Anderson.

The asymmetry in England’s build-up play also allowed them to repeatedly exploit their numerical superiority in specific areas tailored to Germany’s pressing structure. By stretching the positioning of their two holding midfielders (the “sixes”), Reitz was forced to cover too much ground to mark both or to shift quickly to the ball-near midfielder.

Because Germany, for the reasons mentioned above, struggled to steer the press in a specific direction, Reitz was also unable to position himself closer to the ball-near player during goal kicks. Instead, he was forced to choose which of the two midfielders to mark man-to-man.

The wide, asymmetric positioning of the holding midfielders and advanced full-backs makes both midfielders available for passes, forcing Reitz to choose whom to mark. German forwards can’t shadow the opposing midfielders, while German wingers must decide between marking the spaced-out midfielders or full-backs.

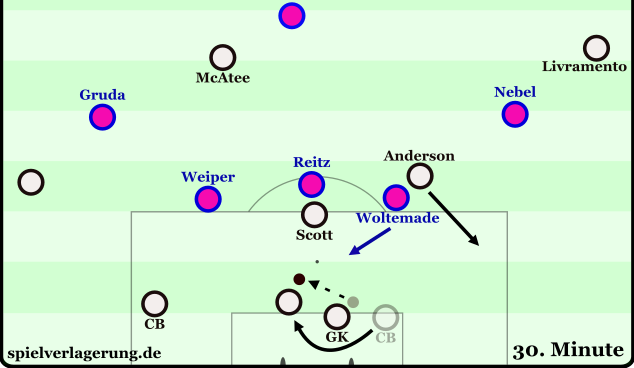

England’s positional rotations during build-up play after goal kicks were most often initiated by holding midfielder Anderson. When Germany applied pressure (as shown in the diagram above), Anderson would frequently drop into the right half-space, almost into a right-sided centre-back position, while fellow holding midfielder Scott positioned himself more centrally, and No. 10 McAtee dropped into the higher left half-space.

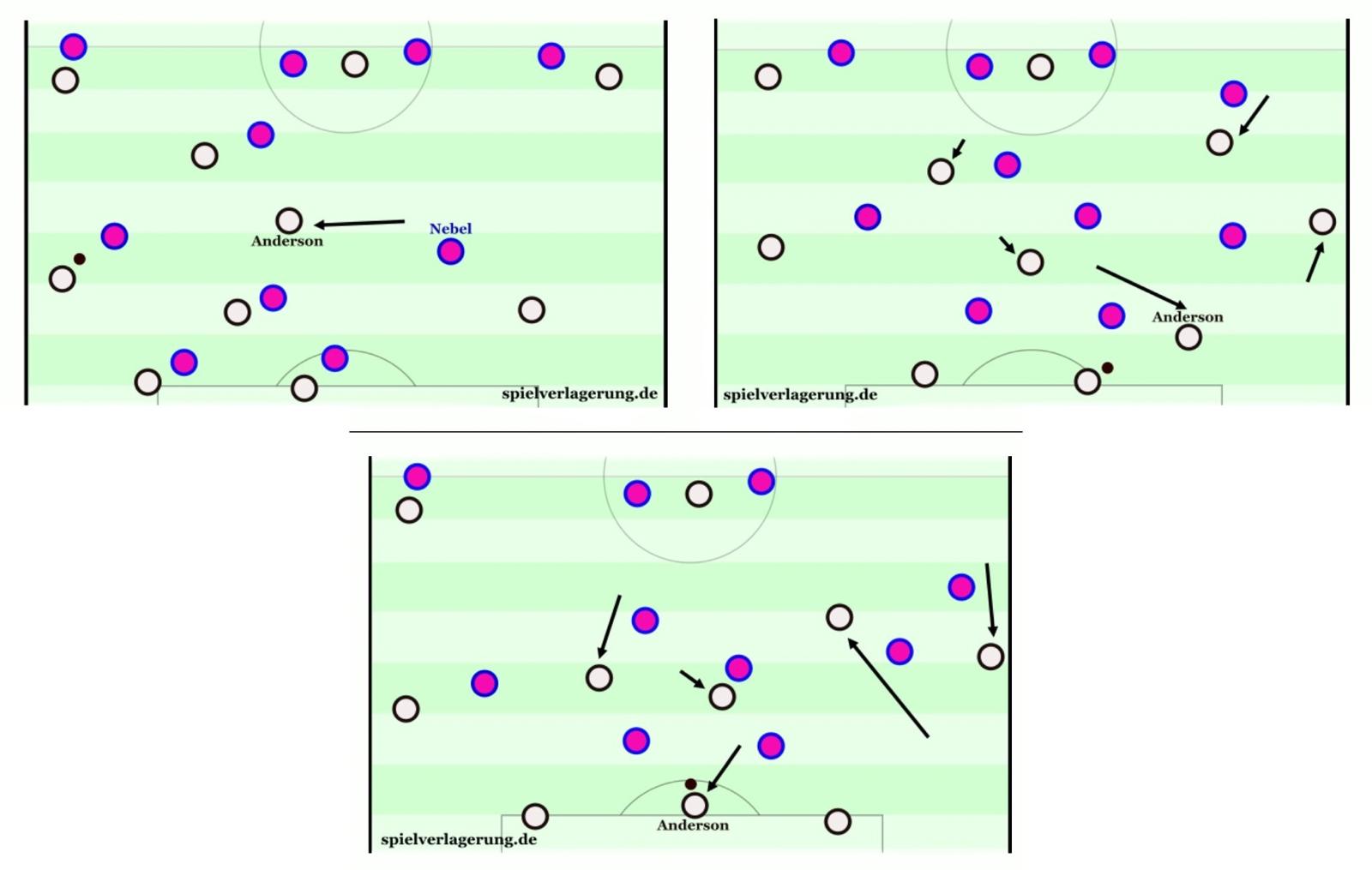

When Anderson instead dropped centrally in front of the goalkeeper, the right centre-back would shift wide, which in turn affected the positioning of other central players and full-backs. The specific rotations of the key players, including their reference points and triggers, are discussed in more detail in the section on England’s build-up against Germany’s high pressing.

A key aspect of England’s build-up against Germany’s pressing was their ability to evade pressure through these rotations. Since Germany used man-oriented marking, they followed the English players during these movements, which repeatedly opened up spaces that England could then exploit. For example, when McAtee dropped deep into the far-side half-space, it pulled Martel—who was defending space-oriented in the center—out of position.

The aim was to repeatedly open up central areas by drawing German players out of the middle. When the full-backs, due to the rotations, were positioned deep and wide in possession, the ball-near holding midfielder would shift outward, thereby opening the central channel. This would often be followed by an overlapping run by the full-back into the half-space, allowing him to be found deep in the center with his marker behind him and plenty of space to operate.

Luring central players out of position and opening up space through rotations is one of the core principles of England’s build-up play. It significantly disrupted Germany’s ability to gain access through their man-marking approach during pressing.

Holding midfielder Anderson’s run outward opens the center, which can then be exploited by the full-back’s typical forward run.

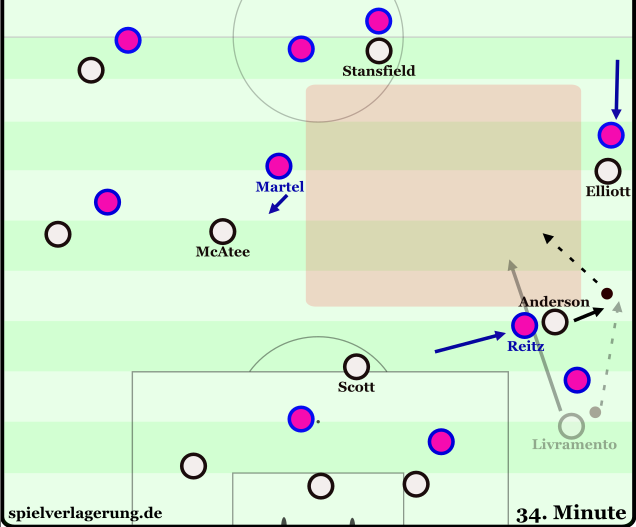

England also added flexibility by repeatedly using long balls from their build-up play. Especially when both the full-backs and the holding midfielders were positioned deep, they opted for long passes as soon as Germany’s wingers and central players were lured far enough out. The 2–0 goal resulted from one such long ball, which was held up by striker Stansfield and laid off to the advancing Elliott and McAtee in the half-space, who now had plenty of room to operate in the open central area.

Although these long balls weren’t always as successful as in the lead-up to the 2–0, they had the effect of preventing Germany from pressing too aggressively, as players had to remain ready to cover depth in case of another long ball. For example, Martel pushed forward only hesitantly toward the dropping No. 10 McAtee, giving him significantly more time on the ball in central areas.

Against man-oriented marking systems, it is particularly important to apply intense pressure on the ball carrier, since progression is otherwise easier than against a zonal setup.

As described, England repeatedly managed to exploit their numerical advantage in the build-up. However, Germany’s pressing approach also contributed to their lack of access. The primary aim of Germany’s pressing when closing down is less about disrupting the build-up itself, and more about winning the ball in a way that immediately creates a transition opportunity.

To do so, Germany tries to use its forwards to immediately block passing lanes to the flanks, forcing the play through the third man or central passes.

Recovering possession through intercepting a pass has the advantage over winning a tackle in that it tends to allow better control of the ball and therefore more often leads to a transition opportunity. Additionally, central ball recoveries naturally result in a shorter route to goal and, statistically, in higher-quality chances in front of goal.

However, this type of pressing also means less pressure is placed on the ball carrier, since the focus is on directing play and winning the ball after a pass. As a result, England’s ball carriers had more time to locate the free +1 player, made available through asymmetry and rotations.

In hindsight, it might have been more effective to place greater emphasis on actively disrupting the build-up itself, because England repeatedly managed to bypass the German press dangerously. At the same time, Germany had the ability to control the game through their own possession, so it wasn’t absolutely necessary to rely on winning the ball high up the pitch to create chances.

England’s build-up against attacking pressing

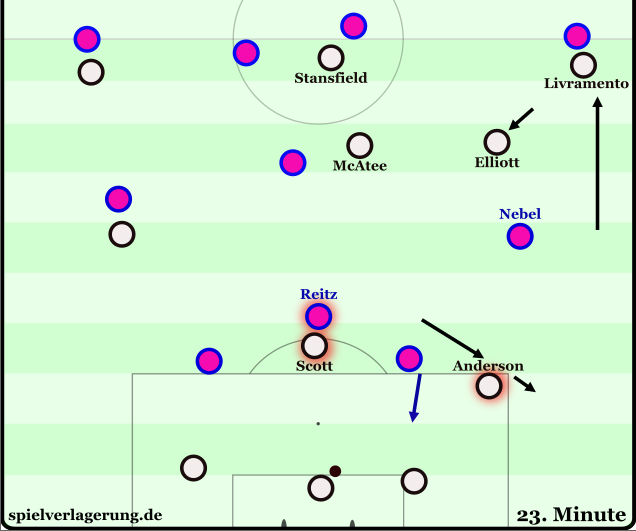

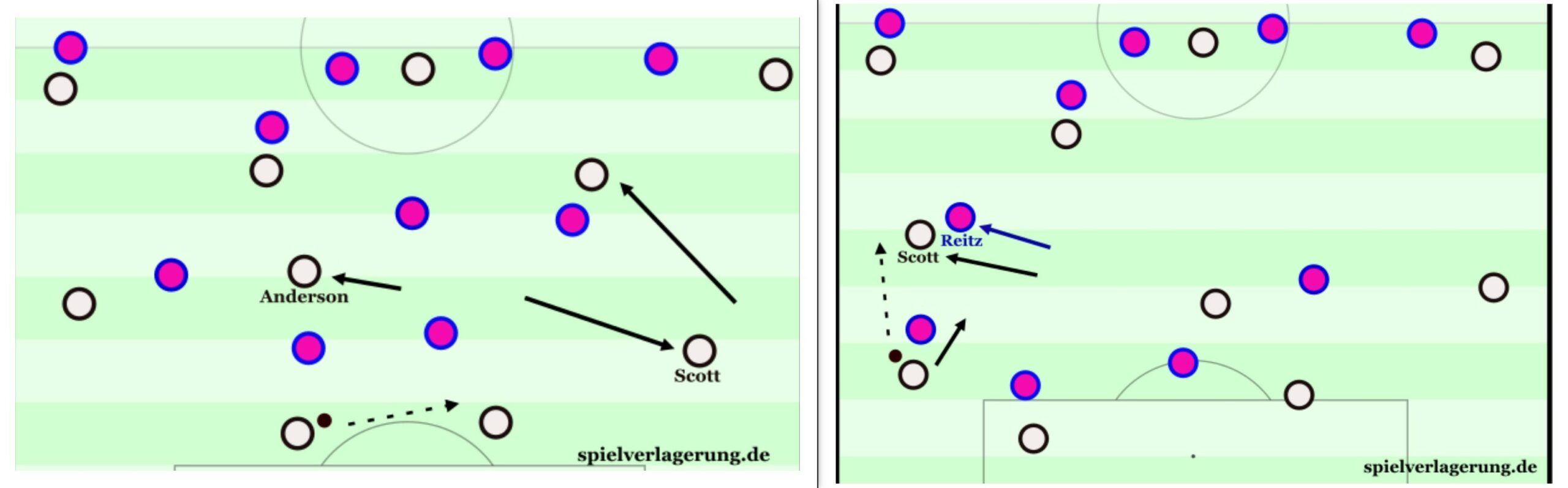

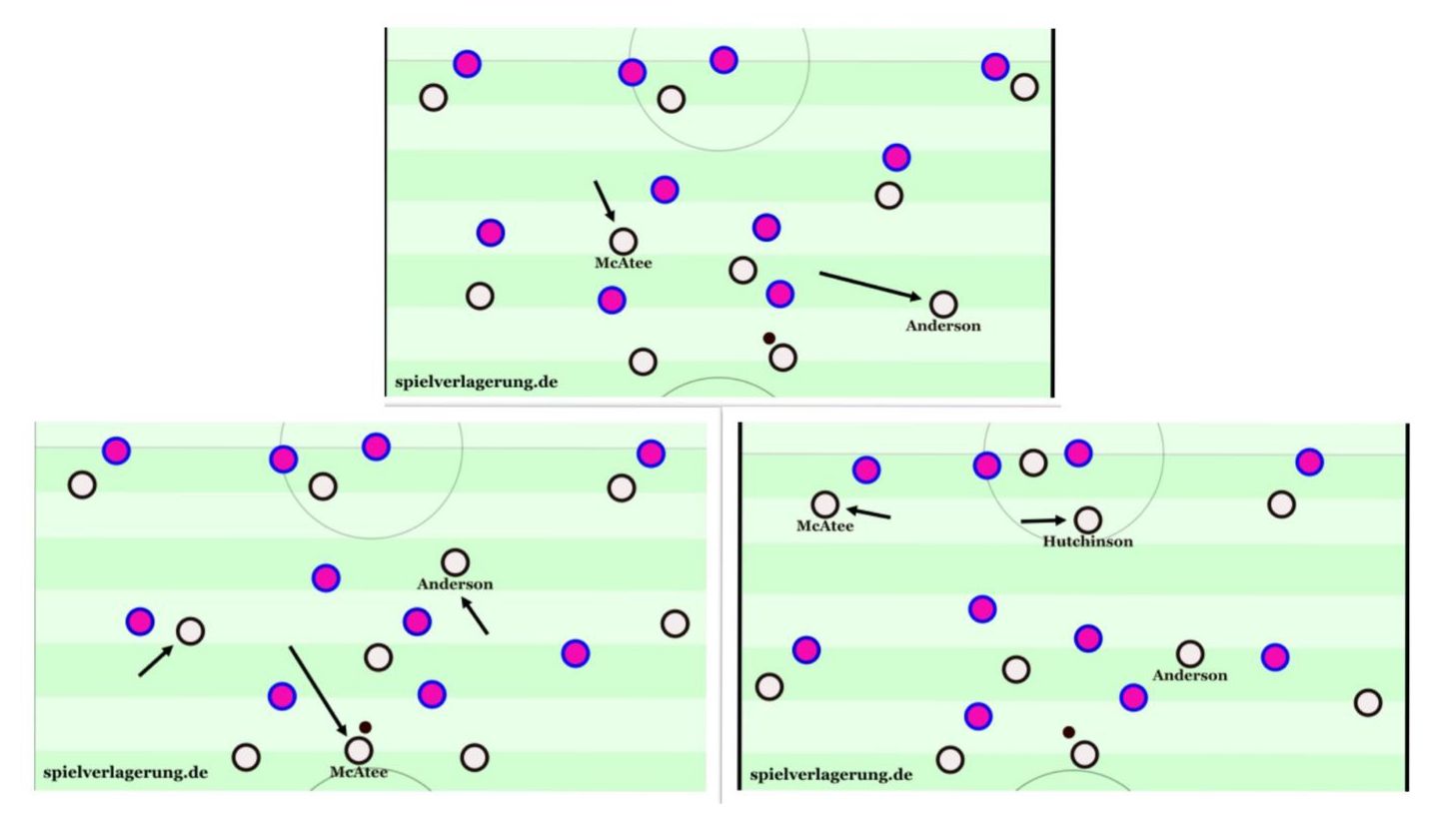

Germany’s attacking pressing operated on principles similar to those of their closing down (Zustellen). From a 4-4-2 formation with a slightly advanced Reitz on the left half-space, the forwards aimed to channel the opponent’s build-up play out wide in order to isolate the wide build-up players and engage them in man-to-man marking.

On the last defensive line, Germany aimed to maintain a +1 numerical advantage, which is why the far-side holding midfielder was usually responsible for covering depth. The German wingers were expected to track back from the full-backs to press the half-backs in the three-man defensive line that frequently formed.

The exemplary German attacking press

Even when applying attacking pressing from open play, Germany was rarely able to gain effective access to England’s build-up. This was primarily due to England’s positional play during build-up. England’s main objective in possession is to lure opponents out of position and then exploit the spaces that open up. This goal is achieved through positional rotations that make it especially difficult for the opponent to apply effective pressure on the ball carrier during pressing. The frequency of these rotations strongly resembles the rotation-heavy positional play famously associated with Paris Saint-Germain.

The following outlines the key running paths, rotations, and reference points of the most important players.

The center-backs were rarely involved in the rotations. Only when one of the holding midfielders dropped into the build-up line did the center-backs position themselves wider. Likewise, striker Stansfield provided a fixed presence in the central deep-lying position.

Most rotations initially originated from the holding midfielders, particularly Anderson. Most frequently, he dropped into the right half-space just ahead of the center-backs. This caused the right full-back to position wider and winger Elliott to drop deeper into the half-space at the level of the last defensive line. As a result, Woltemade and Nebel had to press two players, creating a 3 vs. 2 overload.

There were also occasions when Anderson dropped into the central center-back position. Consequently, the full-backs rotated into the half-spaces, or No. 10 McAtee dropped deeper. Notably, Anderson could be found almost anywhere on the pitch. At times, he overloaded the far side, which was then followed by a role swap between him and holding midfielder Scott.

Holding midfielder Scott often positioned himself in spaces that were left vacant after a sequence of rotations. Usually, Scott remained central or rotated roles with holding midfielder Anderson. It also happened that Scott took up an open full-back position when both the winger and the full-back rotated deep.

A particularly noticeable tendency of both holding midfielders was that, when in possession, they rotated toward the flank if a wide player was positioned close to the first build-up line, making themselves available along the sideline. This had the advantage of stretching the center even further.

This was especially important because England frequently won second balls after losing possession in build-up play. In the resulting transition situation, the central area was completely free, leading to several dangerous counter-attacks through the now open middle of the pitch.

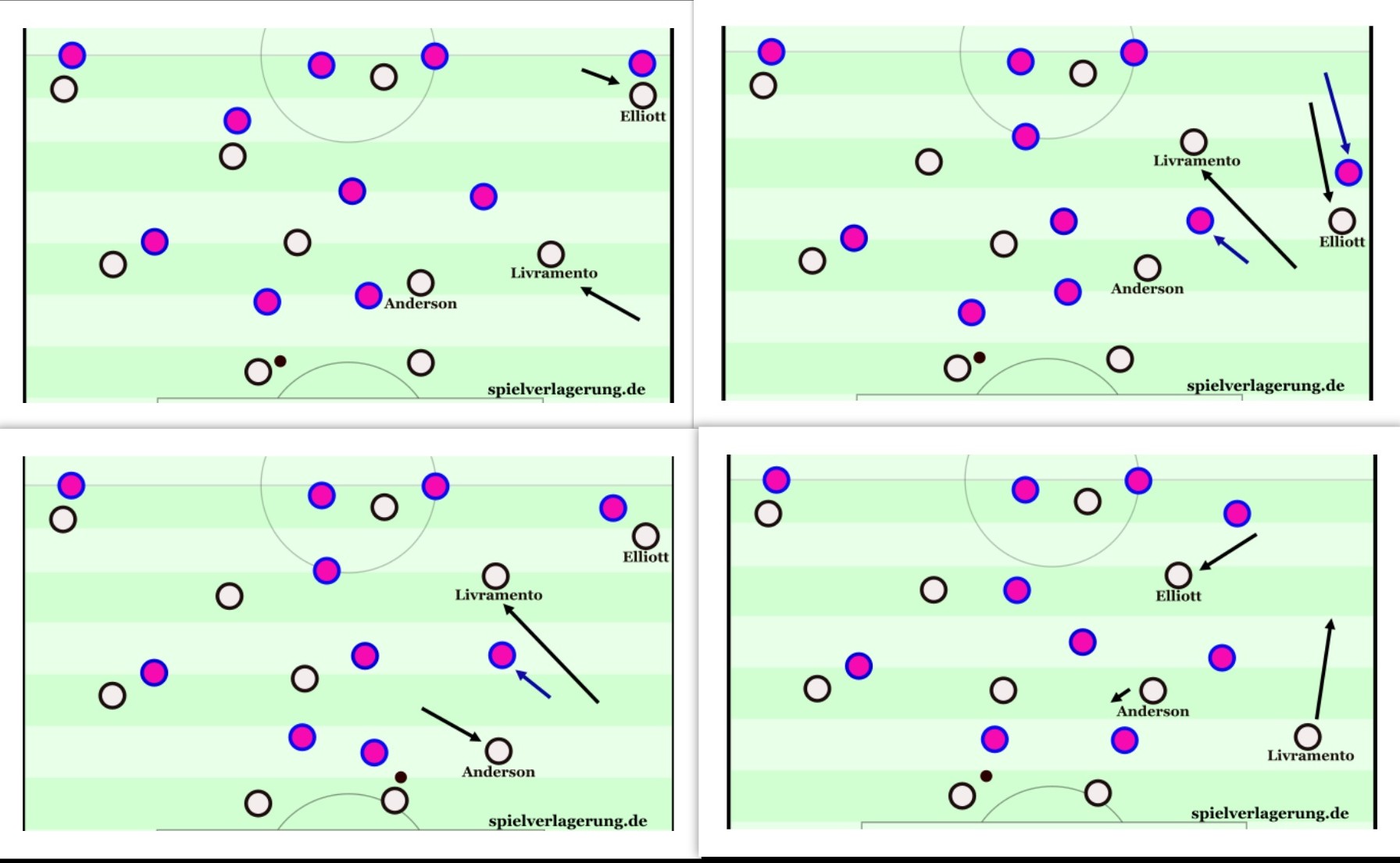

Livramento, as the right full-back, primarily oriented himself around Anderson and the right winger Elliott. In relation to Elliott, Livramento always behaved in a complementary manner: when one occupied the wide position, the other took up the half-space. It was also common for Livramento to invert and drop into the deeper half-space, with Elliott moving wider in response, and vice versa.

Anderson served as a secondary reference point. Whenever Anderson dropped back to form a wide back three, Livramento either moved inverted or stayed wide and deep. If Anderson remained central, Livramento positioned himself near the center-backs in the half-space, from where he could rotate forward into depth if the outside lane was free.

On the left side, full-back Hinshelwood and winger Hutchinson rotated according to the same principles as Livramento and Elliott. Hinshelwood also frequently inverted into the deeper half-space or moved wide and deep. Both full-backs, Livramento and Hinshelwood, often initiated rotations through their inverted runs when the ball was with the near-side build-up player.

Runs into depth, however, were usually triggered only when other players moved to offer passing options. The No. 10 McAtee also played an important role as a reference point. When McAtee (and/or Hutchinson) moved into the left half-space, Hinshelwood rotated oppositely into depth.

McAtee, as a left-sided No. 10, had a freer role. He oriented himself around the holding midfielders to occupy or overload the central area when needed. He also rotated positions with left winger Hutchinson. Often, McAtee initially moved far into the left half-space to pull defenders out of the No. 10 zone behind him and then sometimes rotated further back toward the central center-back position.

In response, either full-back Hinshelwood or holding midfielder Anderson rotated forward into depth. Alternatively, winger Hutchinson could rotate into the half-space, prompting full-back Hinshelwood to rotate wider.

Conclusion

The English rotations created difficult conditions for Germany’s man-oriented attacking pressing. Man-marking was repeatedly manipulated, which in turn stretched and opened up spaces. Thanks to the flexibility of long balls and superiority in second balls, England’s build-up play additionally benefited in the first half. This led to repeated situations resembling counter-attacks, as England had plenty of central space available after bypassing the press.

The early goal also forced Germany to press higher more frequently and reduced their tendency to drop deep. Germany’s pressing behavior against England’s build-up thus became one of the decisive factors influencing the course of the game in the first half.

Author: MH is a football aficionado at heart. His apartment resembles a football library, with shelves filled with books on the great tacticians from Rinus Michels to Pep Guardiola. Of course, the book from Spielverlagerung.de is not missing. For MH, football is not just a game, it’s a way of life. He can be found on X under Mh_sv5 and LinkedIn.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Brooklynn Saunders August 16, 2025 um 10:20 pm

Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.