Retro Analysis? How Nagelsmann’s Hoffenheim Outplayed Liverpool’s Press with Expansive 3-1-4-2

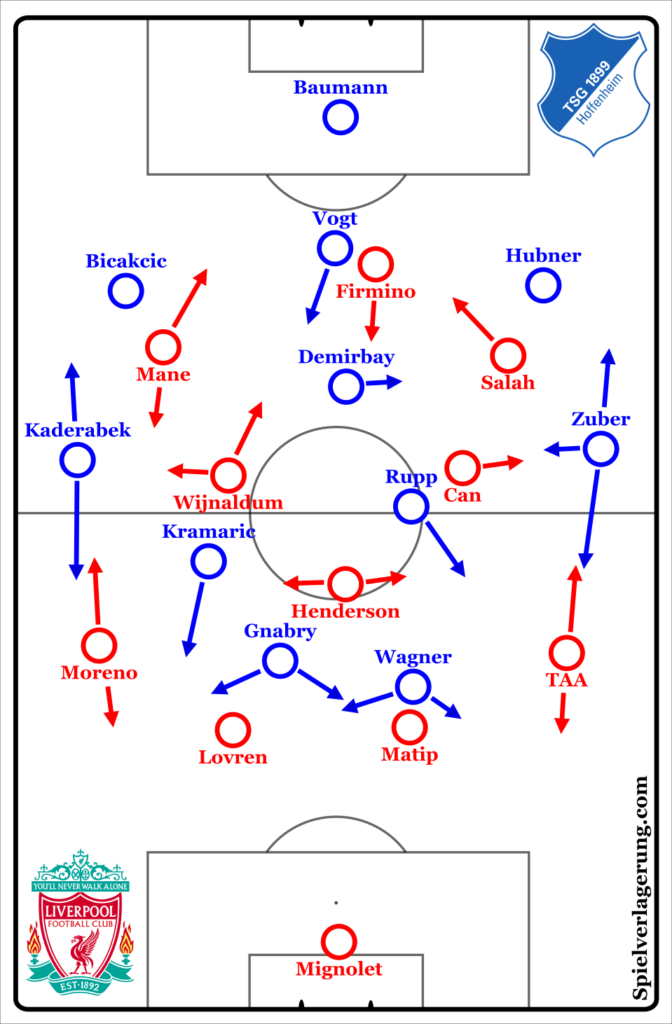

Early in the 2017/2018 season, Julian Nagelsmann met Jurgen Klopp in opposing dugouts for the first time. The young coach demonstrated some effective ways of playing against Liverpool’s narrow 4-3-3 press using their 3-1-4-2. This analysis will breakdown those tactics, but does it constitute as a retro analysis?

Strategy Overview

Hoffenheim’s main strategy for playing against Liverpool’s press was to find their wing-backs in space.

Given the height of Liverpool’s wingers, the wing-backs are the players in space if you can play onto the blind-side of Salah or Mané. However, upon receiving they soon face pressure from the central midfielder or alternatively, the full-back. Therefore, it was crucial for Nagelsmann’s team to have a structure which would restrict those two positions from being able to pressure the wing-back.

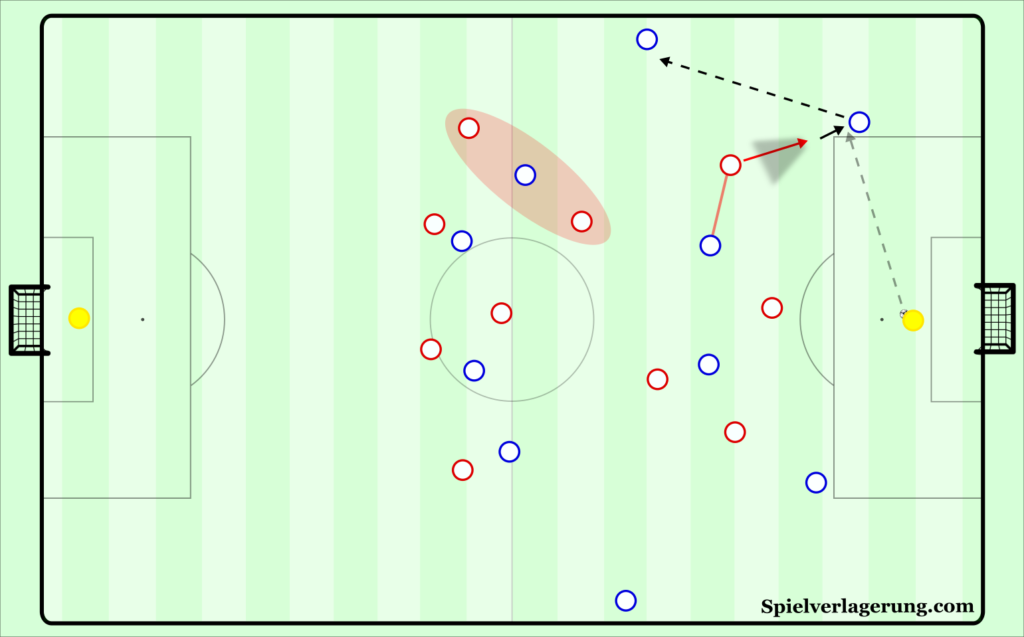

With their 3-1-4-2, they did this quite effectively through a very high positioning of their central midfielders creating more of a 3-3-2-2. Both Rupp and Kramaric would move high during the build-up and occupy positions between Liverpool’s full-back and central midfielder. This position could flexibly pin the two defenders early in Hoffenheim’s build-up and leave the wing-back relatively free.

Once they got the ball to the wing-back, Liverpool’s central midfielder would still aggressively step out, but slightly later and from a narrower position, giving the wing-back slightly more time to act. Hoffenheim then looked to have direct follow-up options to play in-behind or diagonally into the last line with the high central midfielder and centre-forward.

Within the rest of the analysis, I will look to go into some more specifics of how they achieved this strategy.

Possession with the Goalkeeper

In possession with the goalkeeper on the ball, Hoffenheim structured their first two lines as they normally did under Nagelsmann. Central centre-back Kevin Vogt moved higher onto the second line, creating a diamond against Liverpool’s front three. This movement serves a couple of purposes for playing against a front-three pressing structure.

Affords the Goalkeeper More Time

First and foremost, the movement typically gives the goalkeeper more time on the ball. With Vogt moving higher on the blindside of Firmino, the centre-back can more readily move out of the cover shadow of the pressing forward and receive behind him. With this in mind, the Brazilian had to be more cautious in his pressing line to ensure he wasn’t bypassed – meaning he had to approach the goalkeeper more slowly and from a deeper starting position.

With more time, the goalkeeper could more easily play clipped diagonal passes into the wing-backs or more accurately find a long pass into Wagner if the wider option wasn’t on.

Creates Better Angles to Play Behind the Centre-Forward

If Hoffenheim were to play short, this build-up diamond also gave them better angles to diagonally play through the opposition press. Creating three lines of players, the goalkeeper would have his two wide centre-backs as first options, who would then be able to play diagonally to Vogt, behind the centre forward. However, this was not often an option against Liverpool due to the away side’s high wingers. The wide centre-backs would quickly be under pressure and thus short build-up in these situations was risky.

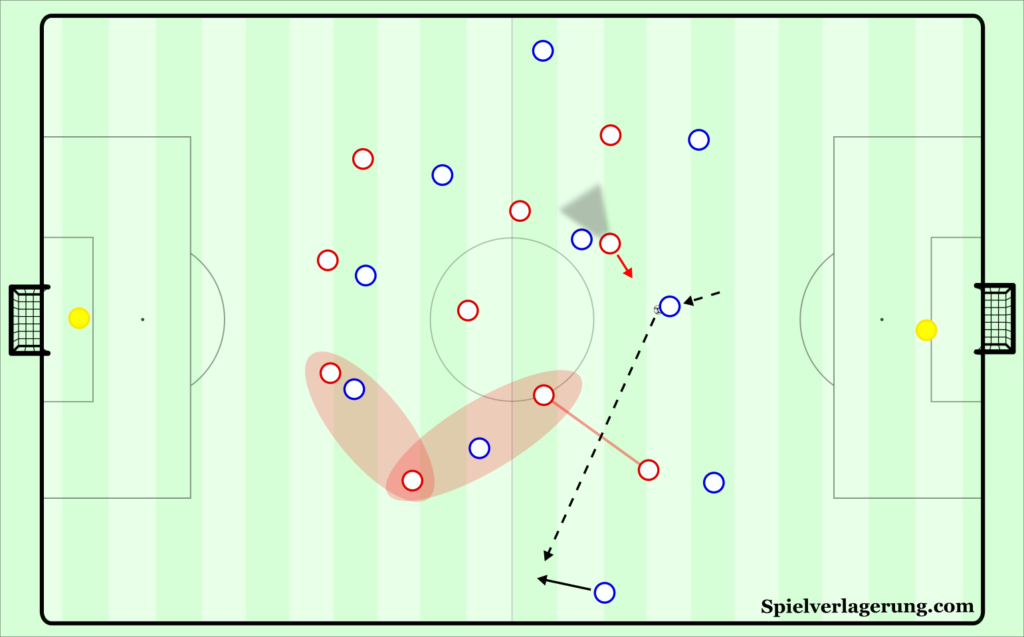

Create a 2-2 box with Demirbay

Alternatively, this movement by Vogt would create a box structure with pivot Demirbay also on the second line. Hoffenheim did this more as the first half developed and they enjoyed spells of possession. This box structure acting against Liverpool’s front three would create four different passing options acting on each gap between and outside the front three.

With an extra player to cover, this could affect the pressing line of Liverpool’s wingers. Instead of being able to press the wide centre-back from outside, blocking the pass to the wing-back, Mané had to begin his press from a more central position so he could instead screen the inside pass to Demirbay. Doing so would open up the easy pass into the wing-back, who could receive just beyond Liverpool’s first line of pressure and have lanes to play inside and accelerate the attack from there.

In reaction, one of the Liverpool central midfielders would step up slightly – but not fully – to Demirbay so that he could jump if Hoffenheim played into him. Through creating more options to play through Liverpool’s first line, Hoffenheim reduced their cover of higher-up spaces by ‘luring’ their midfield. The space they increased with this structure was again with the wing-backs, as the central midfielder had a higher and narrower starting position due to his orientation to Demirbay.

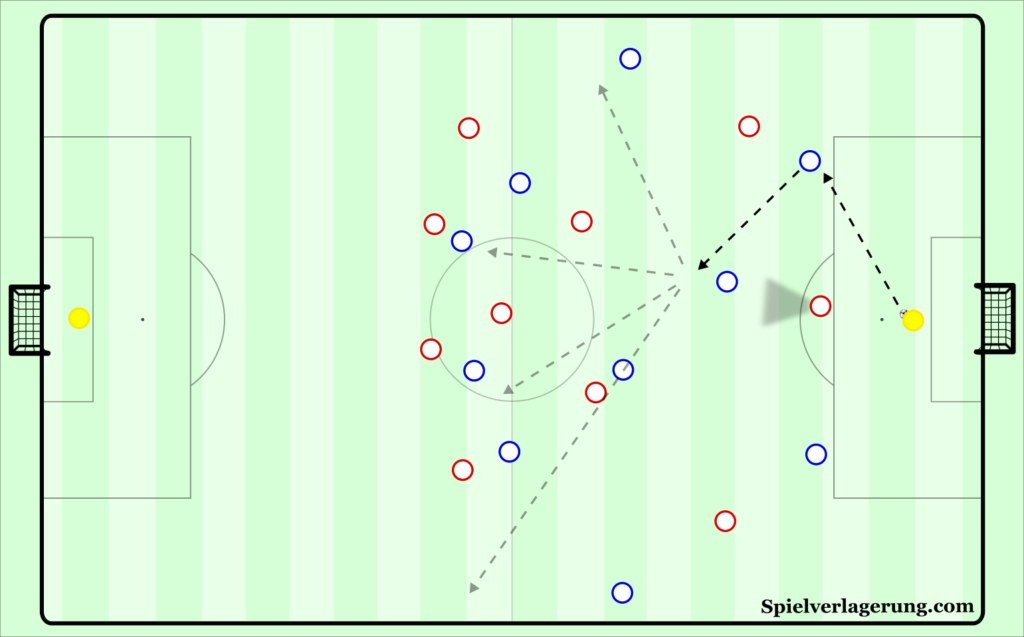

Alternative – Direct into Wagner

Of course, finding the wing-back every time wasn’t possible. Sometimes, slow circulation across the back three, with passes into the back of teammates forced Hoffenheim backwards and Firmino was able to jump early on the back-pass to the goalkeeper.

In other situations, Liverpool’s full-backs and midfielders were able to position themselves well enough where they stopped themselves from being fully pinned. For example, Moreno positioned himself on the outside of Kramaric with Henderson closer on his inside, while Wijnaldum covering Demirbay but again on his outside. For both players, they covered their nearest attacker as closely as necessary but left as little distance as possible to the wing-back so they can engage him if a long ball is played.

The alternative option for Hoffenheim was to play directly into Sandro Wagner, a competent target player. While their structure was mainly to reduce oppositional forward cover of wide areas, it also gave them four central players to attack second-ball situations.

If the situation was more transitional, they would play straight down the middle but if afforded time to create a structure, Wagner would move onto one of Liverpool’s full-backs to have the obvious dominance in the air. In such situations, Gnabry sought to occupy a position between and in-front of the Liverpool centre-backs, while the ball-near central midfielder in a high position would be closer to the duel than his Liverpool counterpart. The ball-far Hoffenheim central midfielder would be high and inside to potentially attack the channel between Liverpool’s ball-far centre-back and full-back.

This structure would increase Hoffenheim’s chance of winning the duel and then having dangerous options from the second-ball, however Liverpool were able to defend the duel quite well from an individual perspective. The one instance Liverpool didn’t in the first half, resulted in a penalty after Kramaric received a knock-down from Wagner and played in-behind to Gnabry running between the centre-backs.

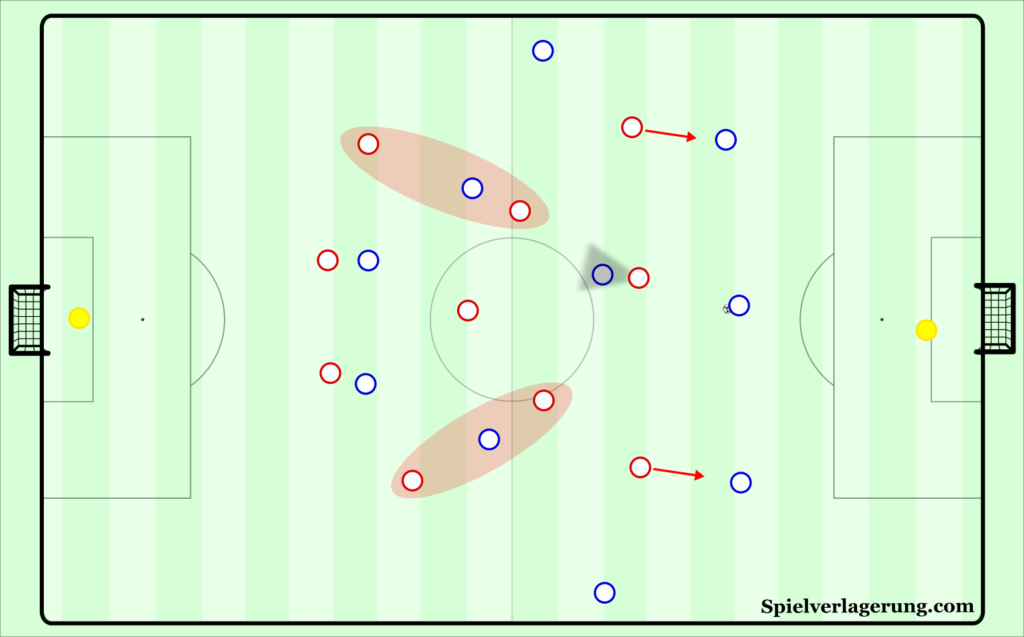

Possession against High Press

In structured possession with the ball in the first line, Vogt didn’t move up. Doing so would likely make the distance between the wide centre-backs too big in that a pass between them would allow Liverpool’s ball-far winger would step up and attack the defender as he receives. Aside from that, however, they were very similar structurally. Both central midfielders acted very high with the intention of pinning Liverpool’s full-backs and central midfielders along with the ball-near centre-forward. Again, the wing-back was in space. But with the Liverpool winger still closing the line between wide centre-back and wing-back, Hoffenheim had a few ways of finding their man.

From Vogt

The benefit of Vogt’s central position in the back three is that he had good access to play directly into the wing-back through the lane between Liverpool’s winger and central midfielder.

With Firmino screening Demirbay, Hoffenheim could circulate to move the Brazilian away from the ball and give Vogt space in front. The defender displayed showed good recognition of passing lanes in such moments as he would take just one or two touches forwards to improve his angle to play into these gaps between winger and central midfielder. These steps forward not only widened his angle but made the pass required a few yards shorter too, making it easier to execute.

This created a dilemma for the ball-near winger in whether he should screen the pass to the wing-back or stay higher to be able to press the wide centre-back. It could have been better to have a deeper starting position in such situations so that he could initially screen this pass to the wing-back. Although this would reduce Liverpool’s pressure on the ball and would leave the simple pass to the wide centre-back free, it could be possible for Salah (for example) to then step up while covering the wing-back to restrict the defenders’ options as his team shifts across.

The only problem here would be how Hoffenheim would adapt. If the wing-back moved further up field in reaction and the wingers dropped further, it would make Liverpool’s press too flat and the Hoffenheim centre-backs would be unopposed. In a way, this actually happened in the second half which I will briefly discuss later.

Wide Centre-Backs’ use of Dribbling to Open Lane

Like Vogt, the wide centre-backs also showed a good appreciation of when to take touches forwards before playing the ball as a way of provoking pressure to increase space in front of them or outside.

The most common situation where you could see this was when under pressure from the winger who screened the pass to the wing-back. With pressure coming from the outside, the defender could take a step forward before playing either vertically into the half-space, or just past the winger who couldn’t react quickly enough to the change of angle.

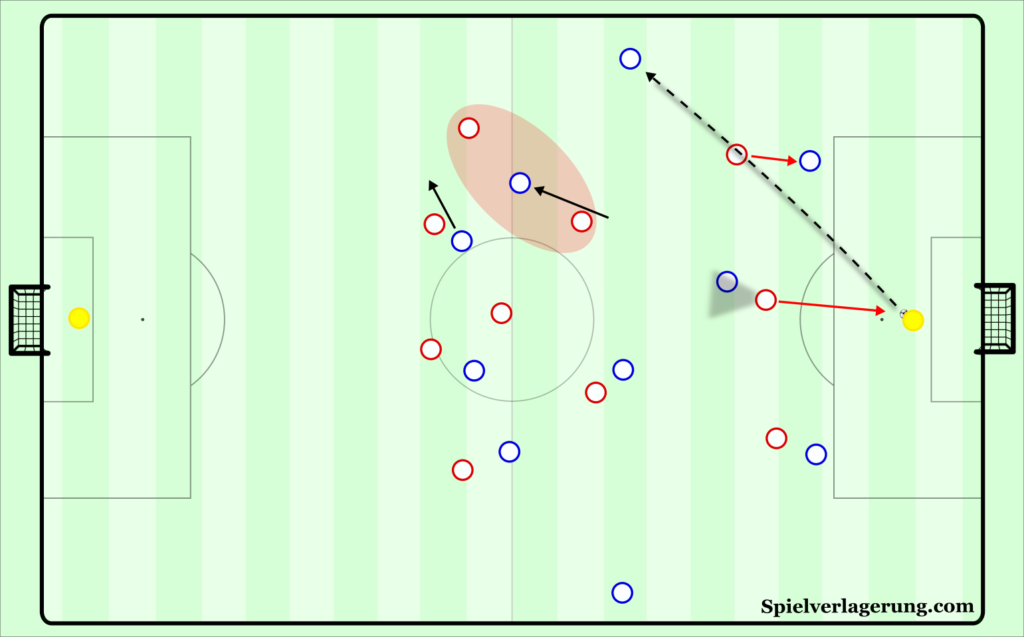

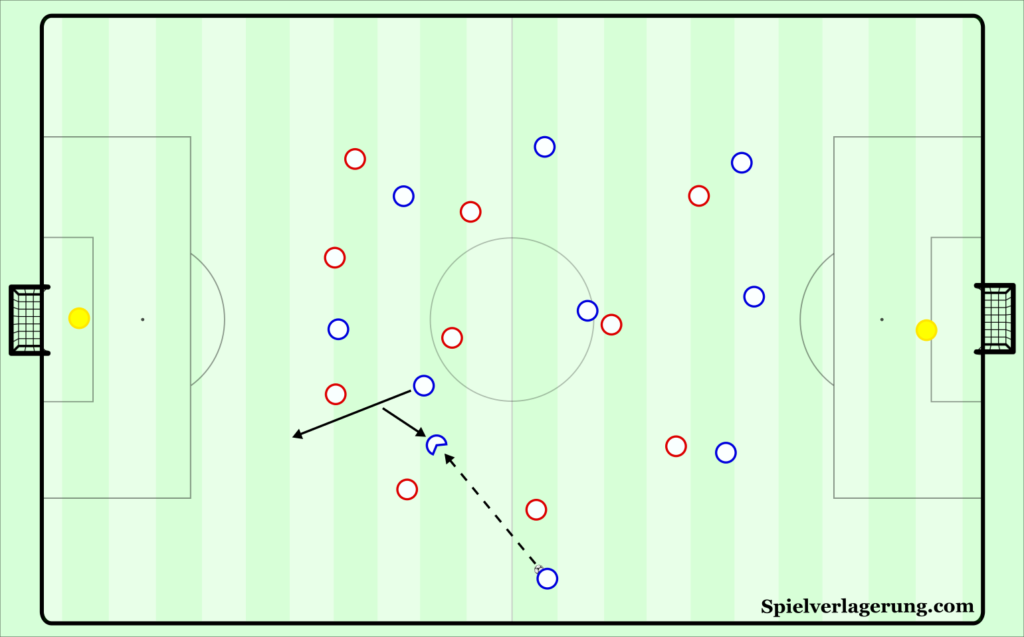

Bounce Pass through Demirbay

After about 30 minutes, Liverpool became situationally more aggressive in their press with Firmino acting closer to Vogt. While this made it more difficult for the central centre-back to directly influence the build-up, Demirbay instead became freer. Without being consistently screened, Hoffenheim’s wide centre-backs could play into him for a bounce pass out to the wing-backs to still outplay the press.

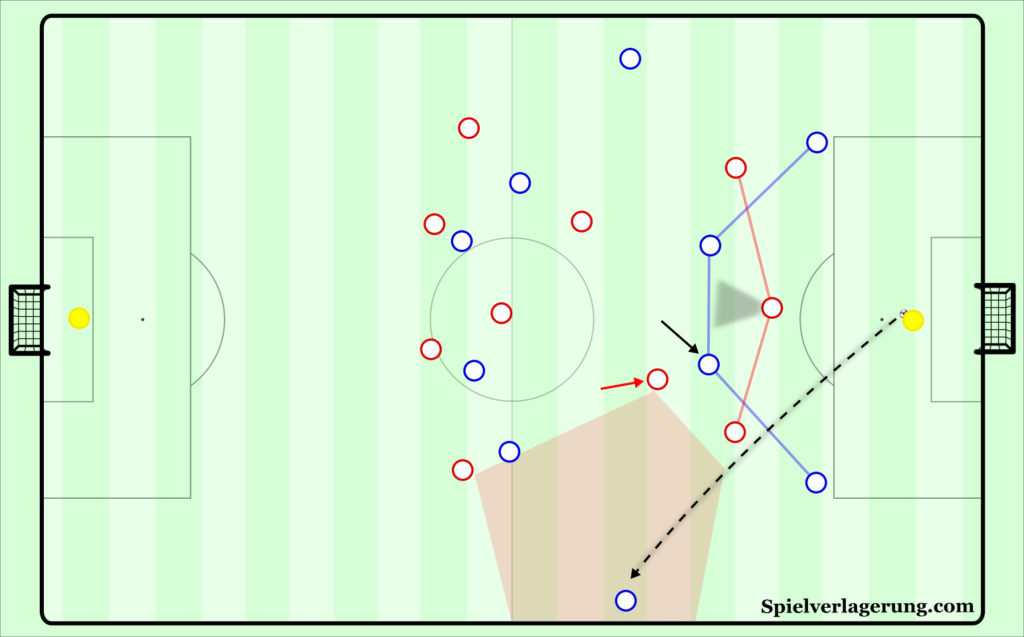

Wing-Backs Lay-Off Option from Inside

As Hoffenheim consistently found their wing-backs in space, Liverpool’s midfield line became slightly wider in reaction. To clarify, the difference was small enough that I doubt it was an instruction from the side-line, and more just a minor adjustment by the two central midfielders. As a result, passing lanes inside became more open for Hoffenheim’s wide centre-backs.

Yet due to the pressure that Liverpool could apply on the inside of their block, time was still limited for forwards receiving between. They could only really afford to play with one touch as they attempted both play with lay-offs as well as flicks in combinations. For lay-offs, a common option for this pass was indeed the wing-back, who would still be free with the Liverpool full-back focused on the play on in his inside.

There were two main benefits for the wing-back receiving in this situation compared to receiving from the centre-backs.

Firstly, receiving while facing forwards allowed him to identify his progressing action quicker. But possibly more important is the context of the players running in-behind. Once the ball was played into the centre by the centre-back, Liverpool’s ball-near defenders step up aggressively to force the ball back out of the shape. With the defenders stepping up, this then means there is more space to run in-behind into and any third-man runners have the benefit of counterdynamic in running in-behind against the defenders who stepped up in the opposite direction.

Follow-up Options for Wing-Back

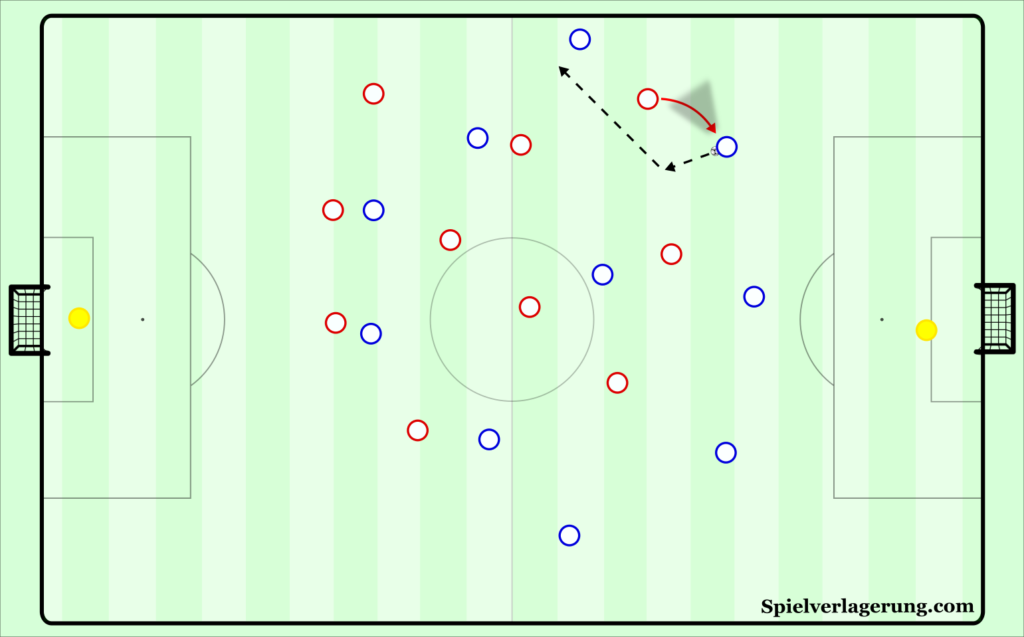

Given the high positioning of the ball-near central midfielder and centre-forward, the wing-backs’ follow-up options were mainly direct, but we can break it down into three main options. As I briefly mentioned in the overview, once the wing-back received the Liverpool central midfielder was approaching, so options to play forwards quickly were crucial.

The first option is of course to play to the central midfielder or centre-forward moving in-behind. Particularly with the pace of Gnabry running from inside-to-outside, this proved to be a dangerous option throughout the game.

But the movements in-behind also opened lanes to play diagonally inside by drawing defenders out. These openings allowed Hoffenheim to play inside against the shifting of defenders and utilise Sandro Wagner as a lay-off player. Although they found Wagner consistently from both sides, the centre-forward sometimes moved too closely to the ball when receiving. Doing so reduced his own follow-up options, as it meant that Rupp (for example) would moving in-behind but Wagner’s blind-side as the centre-forward was facing the touchline.

With the aggressive positioning of ball-near attackers, the other possibility was that the defending full-back doesn’t engage and instead chooses to cover his space. In this case, the wing-back has the option to drive forwards towards the goal and provoke pressure to create options at the end of his carry. This situation didn’t happen much during the game though, as the passing options proved effective enough.

The positioning of four players up against Liverpool’s back four allowed them to create some dangerous situations for direct play into the last line or in-behind, often playing with equal numbers of attackers against defenders.

Theoretical Tangent – Pinning with an Underload versus More Players on Last Line

Without digressing too far – the topic itself could be the basis of a theory piece – the number of attackers you use in pinning the opponent’s deeper defenders is an important and interesting decision in how it affects your entire possession game.

With two good forwards, it is possible of course to pin four defenders with just two attackers. While this leaves you with two players to create an overload in deeper areas on the pitch, ultimately it means that you have to create opportunities against a defense with a two man overload once you do break the press (excluding the number of players arriving from deeper positions).

This was a particular dilemma that Brighton had in their game against Manchester City at the Etihad early this season – they pinned City’s back four and two midfielders with four attackers and were able to break their first and second lines fairly consistently. But then once they did get through, they struggled to convert these open situations into chances due to the underload they had.

So, they could outplay the first and second lines of pressure, but does that constitute as good build-up? It ultimately hindered their ability to create chances.

A good comparison here then, is Hoffenheim. They were still able to pin Liverpool’s central midfielders in the very early stages of build-up due to their high central midfielders’ positioning between them and the away side’s full-backs. However, once the wing-back received the ball and the Liverpool central midfielder stepped out, Hoffenheim had four attackers up against Liverpool’s back four. This four vs four allowed them to create dangerous situations, leading to chances while Liverpool had to backwards press and tactical foul on a number of occasions.

Ultimately, it’s too broad of a topic to isolate to two matches with many other factors to consider. Within the game in question, Hoffenheim could quite cleanly play through their opponents’ press despite the four vs four, a compliment to Nagelsmann’s team but also showing that the balance is of course not a zero-sum game.

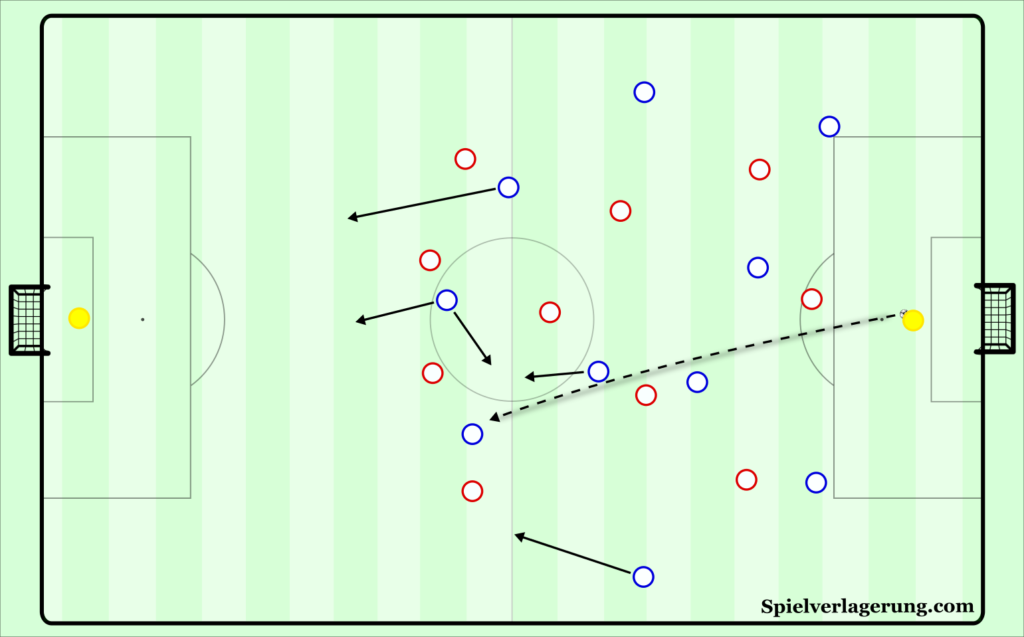

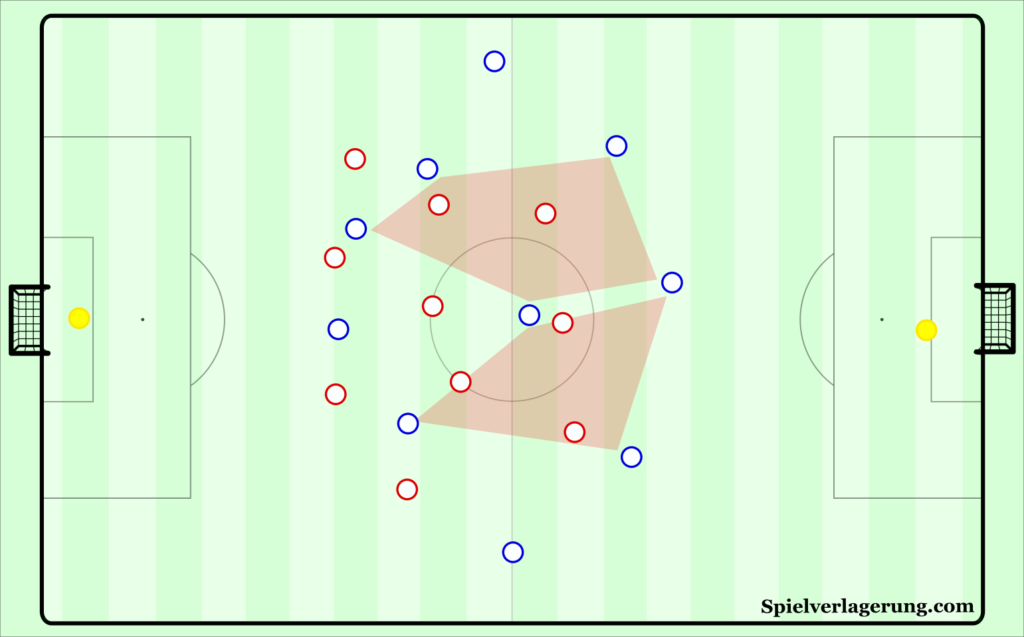

Defending Transitions

Hoffenheim’s structure supported their in-possession strategy well but left one main weakness. With the central midfielders both very high, even from the early stages of possession, it left their rest-defence quite open and without much cover on the sides of Demirbay in midfield. Liverpool’s wingers and especially Sadio Mané, occupied these positions well when out of possession to receive in space upon transition then drive forwards between Bicakcic and Vogt. Liverpool were at their most dangerous in these transitional situations and created chances as well as a foul which led to Trent Alexander-Arnold’s goal from a direct free-kick.

While Hoffenheim’s structure allowed them to bypass Liverpool’s midfield by playing around them in possession, leaving the midfield open left for consequences once the ball was turned over against their opponent’s narrow shape.

Second Half

For the second half, it seemed as though Nagelsmann had one small change which was to move the wing-backs slightly higher when they had possession within the midfield third. This forced Liverpool’s wingers deeper and they now acted in a more passive 4-1-4-1 midfield block. Through the change, Nagelsmann allowed his team to have more stable possession in the midfield third where the centre-backs could step further into midfield and play between Liverpool’s lines. In those situations, Hoffenheim demonstrated how good their forward players were at creating options for a deep player on the ball. The higher wing-backs also gave the hosts more threat in-behind Liverpool’s last line – passes which their centre-backs could play with less pressure on the ball – one resulting in their goal.

Within their first third, Hoffenheim’s wing-backs didn’t change much from the first half – had they moved higher then they would become isolated and the build-up would suffer with a lack of width deeper. They continued to show their ability under pressure and play down the outside of Liverpool’s press. Misplaced passes and slow play let them down at times, which Liverpool were quick to pounce on and remained a transition threat against their open structure.

Conclusion

Despite the 2-1 loss, Nagelsmann’s Hoffenheim displayed an effective way to play against Liverpool’s narrow 4-3-3 press. Their flexibility in their first line involving the goalkeeper was important in outplaying Liverpool’s front three and their expansive 3-3-2-2 structure demonstrated effective pinning actions and the benefit of having a high presence on the opponents’ last line for follow-up option

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen