Chat GPT: Diagonality Football’s Hidden Dimension of Play

Football is often framed in terms of vertical and horizontal play – attacking “directly” upfield versus spreading the pitch wide. Yet between these axes lies an equally crucial but subtler dimension: diagonality. Diagonal passes, runs, and structures connect the vertical with the horizontal, unlocking angles that pure north-south or east-west approaches cannot. In geometric terms, a player in a central position has roughly eight directions to play the ball (forward, backward, left, right, plus four diagonal angles), whereas near the touchline there are only five (forward, backward, square inside, square outside, and two diagonals) 1 . Those extra diagonal options dramatically expand the attacking vocabulary. Diagonality is not just a hybrid of vertical and horizontal – it is a first-principles concept in its own right, one that influences how space is created, perceived, and exploited at the highest levels of the game.

This article explores the theory of diagonality in football in depth. We will examine diagonal passing and its unique benefits, diagonal movement both on and off the ball, and how teams employ diagonal structures in their positional play. Along the way, we will integrate historical insights and contemporary (2023–2025) examples – from Arrigo Sacchi’s diagonal-minded wingers to Pep Guardiola’s half-space virtuosos and modern innovations at Manchester City and beyond – complete with conceptual diagrams. The discussion will remain rigorous and grounded in first principles, much as we approached concepts like the half-spaces in earlier Spielverlagerung analysis, but with an evolved perspective in 2025. In closing, we reflect on how coaches can train diagonality and the broader philosophical implications of a game played between the lines.

Why Diagonality Matters: In essence, diagonal play allows teams to combine the advantages of vertical and horizontal methods while minimizing their drawbacks 2 3 . Vertical play aims directly toward goal but can be predictable and limit the passer’s field of view; horizontal circulation stretches the opponent but may lack forward penetration. A diagonal approach strikes a balance. It gains ground toward goal and shifts the point of attack laterally, forcing the opponent to constantly adjust in two dimensions. This multi-axis stress is at the core of diagonality’s effectiveness – and the core of our exploration below.

The Geometry of Diagonal Passes

At the heart of diagonality is the diagonal pass. A well-played diagonal ball can seemingly bend the game’s spatial logic, breaking through defensive lines in ways straight passes cannot. What makes diagonal passes so potent? Here are several key factors from a theoretical standpoint:

• Line-Breaking Power: A diagonal pass can eliminate multiple opposing players by cutting through both vertical and horizontal layers of a defensive shape 3 . As a Guardiola-era analysis noted, “Diagonal passes eliminate both vertical and horizontal lines of the opponent’s defensive shape.” By slicing between lanes, a single diagonal ball can bypass an entire bank of defenders, transporting the attack into under-protected zones 3 . For example, when Bayern Munich’s Jérôme Boateng hit a driven diagonal from left center-back toward Philipp Lahm against Dortmund, the pass moved through several Dortmund defenders at once, finding Lahm in space beyond the pressing midfield 4 5 . In essence, the diagonal trajectory opens a new lane where none existed, zooming the ball into gaps between the opponent’s compact lines.

• Combining Vertical Gain with Horizontal Shift: Unlike a purely vertical ball (which gains ground but doesn’t change the angle of attack) or a square pass (which changes angle but not field position), a diagonal pass does both. It advances play toward goal while relocating the attack laterally, forcing defenders to adjust their orientation and footing 6 . The opponent must twist and turn to meet the ball’s path – adjusting both their depth and lateral positioning – whereas a vertical pass only tests their depth and a horizontal pass only their lateral cover 6 . This dual stress often induces asymmetry in the defense, disrupting their shape. A coaching maxim encapsulates it: a diagonal pass forces defenders to move in two planes at once. The result is greater defensive confusion and a higher chance of error 7 .

• Optimal Field of View for the Receiver: A diagonal ball usually arrives to the receiver’s front- foot side, meaning the receiving player can open their body toward the opposition goal as they control it 8 . Because the pass comes at an angle, the receiver is less likely to be facing their own goal upon control; instead they can take it on the half-turn, already oriented to play forward. In contrast, a vertical pass to a player between the lines often forces them to receive with back to goal, and a horizontal pass to a wide player often faces them toward the touchline. A diagonal delivery minimizes those issues. As our earlier analysis of half-space play noted, a player in the half-space “maintains a diagonal, goal-facing view of the field in his passing game,” whereas a player on the wing or receiving a straight ball often has to turn away from goal 9, 10. The diagonality inherently grants the receiver a broader vision of options: both the upfield space and the opposite side are in their eyeline upon control 11 . This improved field of view translates to quicker, safer subsequent passes 2 – a cascading benefit.

• Access to Underloaded Spaces: Because defenses tend to concentrate around the ball, areas diagonally away from the current ball location are often less populated by defenders. A vertical pass goes into the teeth of the nearest defensive block, and a horizontal pass goes into the well-shifted far side of the same line – but a diagonal can find the seam between those zones. Napoli’s possession play under Sarri (mid-2010s) was a great illustration: they would frequently play a diagonal pass from deep midfield into an attacker dropping between the lines at an angle. This worked so well because, as one analysis noted, “diagonal passes…tend to go into less densely populated areas than vertical ones,” allowing the receiver more time and space 12 . A typical Napoli sequence might see Jorginho or Hamsik in the left-centre circle fizzing a diagonal ball into the “ten space” (just behind the opponent’s midfield line) toward a player like Marek Hamsik or Allan arriving there 12. That diagonal entry pass would often find the target in a pocket of space between converging defenders, whereas a straight north-south ball into the same band would likely have been harder to receive due to a tighter marking orientation. In short, diagonals are an excellent tool to penetrate between the lines because they naturally seek out the pockets just outside a defense’s immediate focus 12 .

• Cutting Distance & Time: Especially over long distances, a diagonal trajectory can be more efficient than its vertical equivalent. A long straight pass downfield is relatively easy for defenses to intercept or force wide because it travels entirely within one “corridor” of the pitch. A long horizontal switch, meanwhile, gives defenders time to slide across. A diagonal long pass (for instance, a diagonal switch from a right-back toward a left winger upfield) effectively short- circuits both those defensive reactions – it moves the ball on a line that is at once forward and wide. This means fewer defenders lie directly in its path, and it forces defenders to judge an unusual flight path. A previous study pointed out that playing a successful 30-meter pass vertically or horizontally is difficult because opponents can quickly block pure vertical or horizontal lanes, but a diagonal pass can “cut” across vertical and horizontal lines, increasing the chance the ball reaches its destination 13 . An added bonus is that a diagonal through-ball or switch often gains both vertical and horizontal ground simultaneously 14 – for example, a diagonal through-ball from the right half-space into a striker making a run toward the left side of the box might advance 15 meters upfield and 10 meters laterally in one go. This dual gain is invaluable in stretching and destabilizing defenses.

To illustrate, consider a common scenario: a center-back has the ball and the opponent defends in a compact 4-4-2 block. A direct vertical pass into a marked striker’s feet is risky, and a simple horizontal pass to the full-back doesn’t progress play. Instead, the center-back might play a diagonal pass into the attacking midfielder sliding into the half-space behind the opposing midfield line. That diagonal both breaks the midfield’s line vertically and shifts the angle of attack into the half-space, catching defenders off balance. In receiving that ball, the attacker is already half-turned toward goal, able to drive forward or lay off to a runner. Meanwhile, multiple defenders have been taken out by the pass’s angle. This one example encapsulates why high-level teams so prize diagonality: it unlocks defenses by exploiting geometry. A well-timed diagonal ball can feel like inserting a key into the precise lock that opens up the opposition.

It’s important to note that not all diagonal passes are inherently good – context and execution matter. A sloppy diagonal can be intercepted just as easily as any telegraphed ball. But at the elite tactical level, coaches train players to support every pass with diagonal options and to time their runs and body shape to capitalize on diagonal deliveries. As we will see, the effectiveness of a diagonal pass is tightly linked to movement and structure around the ball. Diagonality in football is a synergy: the pass angle, the receiver’s run, and the team’s shape must all align to truly stretch the opponent.

Diagonality in Movement (Off-Ball and On-Ball)

If diagonal passes are the ammunition, diagonal movement provides the trajectories. Players’ movements – both off the ball (running into space) and on the ball (dribbling) – are often most effective when they have a diagonal component. Movement along diagonal paths tends to disorganize defenses more than straight-line runs, because it forces defenders into uncomfortable decisions: who should pick up a runner that is not coming straight at one zone or another, but between them? Let’s break down how diagonal movement manifests, starting with off-ball runs.

Diagonal Off-Ball Runs

One of the oldest and most fundamental examples of diagonal movement is the run made by a wide attacker diagonally toward goal. Rather than sprinting straight down the touchline or directly vertically through the center, an attacker will often arc or angle their run to attack space behind the defense at a diagonal. This type of run has multiple effects:

• Pulling Apart Man-Marking: In the era of Arrigo Sacchi’s AC Milan (late 1980s) and the many systems it inspired, wingers were instructed to run diagonal routes to shake off their markers 15 . If a winger starts near the left touchline but then cuts inside on a diagonal toward the center-forward zone, a man-marking full-back faces a dilemma – follow inside into traffic (potentially clashing with a center-back’s zone) or hand off the runner (which, if mis- communicated, leaves the runner free). Sacchi specifically drew up patterns where, for instance, the left winger would dart diagonally toward the penalty spot while the center-forward might fade slightly wide, causing the defending center-back and full-back to hesitate and often lose track of assignments 15 . By “throwing their man-markers off” with diagonal routes, Sacchi’s wingers created confusion and opened gaps for through-balls. That principle remains just as true in 2025: a diagonal run tends to occupy multiple defenders’ attention and mess with the defensive line’s integrity.

• Exploiting the Blind Side: A diagonal run from an attacker often targets the far-side gap of a defender’s coverage – effectively approaching the defender from their blind spot. For example, a common modern pattern is the diagonal run of a winger or outside forward from the wing in behind the opposite full-back. Think of a right winger timing a run diagonally behind the left-back when a through-pass is coming from central midfield. The left-back, who is watching the ball, suddenly has a runner appear over their shoulder, moving from an area the left-back wasn’t fully covering (the space between left-back and left center-back). Liverpool under Jürgen Klopp have used this with players like Mohamed Salah, who often starts wide but darts diagonally between the opposing left-back and center-back onto through balls. Because the run is diagonal, the left- back can neither stay with the winger (without leaving the flank completely) nor can the center- back easily pick it up (it’s not purely vertical through their channel). The result is often a free runner behind the line.

• Maximizing Distance from Defenders: Diagonal positioning and running inherently force defenders to cover more ground. A simple bit of geometry: if you are 5 meters behind a defender and 5 meters to their side (a diagonal separation), the direct distance between you is about 7.1 meters (by the Pythagorean theorem) 16 . This seems trivial, but in football terms those extra 2+ meters are precious – it’s additional ground a defender must make up to challenge you. By comparison, if you stand 5 meters directly behind a defender (vertical alignment), they need only drop straight back 5 meters to close you down. If you stand 5 meters wide of them (horizontal), they step sideways 5 meters. But if you stand 5 meters behind and 5 wide (a diagonal), they must cover ≈7 meters on a diagonal retreat 16 . This is a longer, slower path – buying the attacker more time. Smart forwards constantly seek these diagonal starting positions relative to defenders. And when they sprint, they often curve or angle their runs to maintain that maximal distance. We see this in how strikers peel off the shoulder of the last defender – not running straight forward into the center-back, but drifting diagonally into the channel between full-back and center-back, where no single defender is ideally positioned to intervene.

A famous historical example comes from Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona (2008–2011). In that team, the wide forwards (e.g. Thierry Henry on the left, Pedro Rodríguez or David Villa on the right) rarely just hugged the line or made straight runs. Instead, they occupied what we term the “intermediate positions” – essentially the half-spaces – by moving diagonally inside from their starting wide positions 17 . In the 2009 and 2011 Champions League finals (both won by Barcelona), one could see Henry or later Villa constantly drifting from the wing toward a central diagonal lane, in concert with Lionel Messi dropping slightly deeper. This meant Barca’s front three often formed a narrow, diagonal trio slicing between the opponent’s back four 17 . The effect was devastating: those diagonal movements pinned multiple defenders and created that extra yard of space needed for Barca’s intricate passing. A horizontally flat front three would have been much easier for Manchester United (their opponent in those finals) to mark zone-to-zone. Instead, the likes of Messi and Villa popped up diagonally between United’s midfield and defense, or between their center-back and full-back, rendering conventional marking schemes ineffective.

In modern examples, we see diagonal off-ball movement in virtually every top team’s attacking patterns. Consider Argentina’s second goal in the 2022 World Cup final – an illustrative contemporary case. Argentina launched a lightning counter-attack that culminated in Ángel Di María scoring after a sequence of diagonal interchanges. It began with Lionel Messi in a central-right midfield spot flicking a pass that released Julián Álvarez along the right channel. Álvarez then squared a diagonal ball into the path of Alexis Mac Allister, who was sprinting forward through the left half-space. Mac Allister, in turn, played a one-time pass to the opposite side, finding Di María who had raced diagonally in from the left wing to arrive in the box 18 . Di María’s run was essentially a textbook far-post diagonal: starting high and wide, then cutting inside at the perfect moment. The French defenders were caught spread apart – one center-back drawn toward Álvarez’s wide run, the other too far central to cover Di María – and Di María arrived to finish with ample space. This goal encapsulated diagonality in movement: it was the diagonal supporting runs of Álvarez, Mac Allister, and Di María that made the quick counter so fluid and impossible to track. Each run intersected the French defensive lines at an angle, creating a cascade of disarray that a purely vertical break might not have achieved.

Importantly, diagonal off-ball movement isn’t only for attackers. Midfielders and even defenders use it as well. A holding midfielder might drift diagonally away from his marker to open a passing lane (rather than simply stepping backward which might remain in the cover shadow). Or a full-back might undercut diagonally inside behind his winger to join an attack (a pattern often seen with inverted full-backs running into the half-space). The core idea is always to occupy a space that isn’t directly in an opponent’s zone of responsibility – to appear in the seams of the defensive scheme. Diagonal movement is a means of positional manipulation: by not being where the opponent expects (straight ahead or directly lateral), you force the defense to communicate and adjust on the fly. Many defensive errors (two players going to one man, or conversely leaving a runner free) arise from these kind of diagonal rotations.

Diagonal On-Ball Movement (Dribbling and Carrying)

Diagonal movement isn’t restricted to players without the ball. Ball-carriers themselves often dribble or drive on diagonal paths to destabilize defenses. If you watch a skilled midfielder carry the ball upfield, notice how they rarely run perfectly straight; instead, they carry at a slight diagonal angle to engage a defender and simultaneously change the point of attack. There are a few reasons why diagonal dribbling is so effective:

• Forcing Defenders to Angle Their Body: A defender confronting a dribbler who comes straight at them can set their stance and engage frontally. But a dribbler approaching on a diagonal forces the defender to turn their hips and run at an angle. This often creates a half-step of advantage for the attacker, who can then cut inside or outside more easily. A classic scenario is a winger who receives near the touchline and dribbles diagonally infield toward the box. As they drive inside, the nearest opposing midfielder gets pulled over and a gap often opens between that midfielder and his defensive line. We saw this, for instance, with Manchester City’s usage of Kyle Walker in a 2019 match against Crystal Palace. Walker, a full-back, would sometimes drive the ball diagonally from the wing toward the center, rather than straight up the flank. In one notable sequence, his inward dribble drew Crystal Palace’s holding midfielder (Luka Milivojević) outofhisslot,whichcreatedagapbetweenMilivojevićandthenextmidfielder 19 .Walkerthen slipped a diagonal pass into that gap for Sergio Agüero, which pulled out Palace’s center-backs and enabled David Silva to make a diagonal run behind them – a chain reaction all triggered by the initial diagonal carry 19 20 . Dribbling diagonally basically pries open a defensive shape by misaligning the layers; it’s like wedging open a door.

• Preserving Multiple Options: When you dribble straight, you generally attack one specific channel; when you dribble sideways, you are usually trying to switch play. But when you dribble at a diagonal, you inherently keep multiple options alive. You are moving toward goal (so you remain a threat to continue driving or shoot), but you are also moving laterally (so you are opening passing lanes to teammates on the far side or dragging defenders away from someone on the near side). A midfielder carrying the ball on a 45-degree angle can often choose at the last second whether to continue going alone, to slip a vertical pass, or to lay it off wide – because the diagonal momentum draws defenders but doesn’t telegraph the final direction. We often praise players like Lionel Messi for their mazy dribbling runs; a closer look shows many of Messi’s carries start by angling infield (from right toward center) which panics defenses, before he either combines or accelerates. The diagonality of the approach is key – come straight and the defense stays comfortably in its lanes; go diagonally and someone usually steps out, creating a fissure.

• Diagonal Carries to Provoke Pressing: A concept in positional play (a staple of German and Spanish coaching curricula) is the diagonal dribble to engage a defender, sometimes called Andribbeln in German coaching terms (meaning “dribble at”). By moving diagonally toward a defender’s zone with the ball, you force that defender to commit. If they don’t step up, the ball- carrier keeps advancing through an ever-bigger gap; if they do step up, they vacate space behind them for a pass. This is often coached with center-backs or defensive midfielders: if a passing lane is closed, carry the ball diagonally at the opponent’s midfield line to draw a presser, then pass into the space the presser left. The diagonal angle is important because it “splits” the difference between two defenders’ zones, making it ambiguous who should step out. We saw John Stones do this for Manchester City in 2023 when he played as a hybrid center-back/holding midfielder. Stones would sometimes dribble diagonally from his position, engaging an opposition midfielder, which freed up Kevin De Bruyne or İlkay Gündoğan between the lines. These subtle diagonal carries are a form of positional magnetism – pulling the opponent out of shape to create openings elsewhere.

In sum, diagonal movement – by runners and dribblers alike – complements diagonal passing to create a full spectrum of diagonal play. The passes and runs are two sides of the same coin: a diagonal pass is only as good as the diagonal run that meets it, and a diagonal run is most useful when a pass can find it. And when a player carries the ball diagonally, they often set up the next diagonal pass or run. This interplay becomes a defining feature of a team’s attacking rhythm. Teams that master diagonality have a fluid, interwoven quality – think of the zig-zagging one-twos of peak Barcelona or the angled rapid breaks of a top counterattacking side. There’s a constant sense of players popping up at the opponent’s weak side, of defenders being turned around as play shifts diagonally through their shape.

Before moving on, it’s worth noting that diagonal movement applies defensively as well. Well-drilled defensive units shift diagonally when the ball moves laterally. For example, if the opponent switches play from left to right, a defending back four doesn’t shuffle purely horizontally across – the near-side defender steps up and wide, the far-side defender drops in a bit, creating a subtle diagonal chain that maintains coverage. Similarly, a common pressing coaching point is the curved or diagonal pressing run: pressing an opponent not head-on, but at an angle that simultaneously cuts off a passing lane. If a forward presses a center-back, he might arc his run diagonally to block the pass toward the full-back while closing the ball. In essence, diagonal principles permeate all phases; however, in defense these are more about maintaining compactness, whereas in attack diagonality is about creating disorientation. Our focus here remains on the latter – using diagonality as an offensive weapon.

Diagonality in Team Structure

Thus far, we’ve discussed passes and movements, which are momentary actions. But underpinning those moments is the more static element of structure – how a team positions its players on the field. An essential aspect of tactical theory is how teams stagger their players vertically and horizontally to create optimal passing networks. And it turns out that an effective structure almost always has strong diagonal relationships built into it. In contrast, a poorly spaced team – with players standing flat on the same line or directly one behind the other – will struggle to impose diagonal play, or any cohesive play at all. Let’s explore how diagonality manifests in team structures:

Staggering and Triangulation

A fundamental principle in positional structures is to avoid flat lines of players. Instead of, say, five players all aligned across the same horizontal line, or a vertical stack of three players in one channel, good teams create a staggered shape – each player occupying a slightly different vertical and horizontal band. This inherently forms diagonal connections between them. If you imagine a simple three-player support shape around the ball, it is typically a triangle: one player slightly to the left and forward, another slightly to the right and back, for example. This triangle provides diagonal passing lanes between each pair of players. In fact, the triangle is often called the “key shape” in football partly for this reason – it “naturally creates diagonal passing options” which are highly effective for combination play 21 . A triangular structure ensures that from the perspective of the player on the ball, there is a teammate at a forward angle to one side, and another at a backward angle to the other side. These are much safer and more potent options than only having teammates directly lateral or vertical.

Maurizio Sarri’s Napoli, as mentioned earlier, were exemplary in this regard: they spaced themselves in diamonds and triangles so that the man in possession “had an option to play forwards, backwards and to either side”, as one analysis observed 22 . In practice, this meant if the left center-back had the ball, the left-back was slightly ahead and wide (forward option), the defensive midfielder was slightly ahead and towards the center (another angled option), and another midfielder dropped slightly behind and inward as a safety (backward option). These options are all positioned diagonally from the ball-carrier, not directly in line. Thus the structure inherently promotes diagonal passes – whichever option you choose, you’re likely playing a pass at some angle that breaks a line of the opponent’s formation.

This kind of staggering is especially crucial between midfield and attack. A classic mistake of naive team shape is when attacking players all stand in a horizontal line waiting for the ball – it becomes easy for a defense to mark because no passing lanes exist through the line (all the attackers are covered in one flat row). A better approach is staggering the forwards at different heights: perhaps the striker stays high on the last defender, while one attacking midfielder drops off 5-10 yards, and the winger on one side comes slightly inside into a half-space pocket. Now the forward line has diagonal connections: the striker can lay a ball off diagonally to the dropping attacking mid; the winger can make a diagonal run inside which the striker or mid can feed; triangles form among them. This was a key to Pep Guardiola’s teams: his forwards and mids were always offset in space to create interior triangles. In the famous Barcelona scheme, Messi (nominally a forward) would drop diagonally between the lines, Xavi (midfielder) would be slightly deeper but central, and Pedro (winger) would be high and wide – forming a three-point structure that could pass around and through defenders. In Manchester City’s recent tactics, we see Kevin De Bruyne often positioning himself a touch higher and to the right, while İlkay Gündoğan (or Bernardo Silva) sits a bit deeper and to the left of center – so when they combine with the striker, they naturally form diagonal passing patterns.

A contemporary example highlighting structural diagonality comes from a 2024 analysis of Manchester City’s approach to breaking down a deep block. The analyst noted that in a match against Arsenal, City’s possession shape at times became too “horseshoe” – players positioned in a U-shape around Arsenal’s packed defense, with nobody aligned diagonally in the middle 23. City “surrounded”Arsenal’s low block but lacked penetration because their players were isolating in separate horizontal and vertical bands 23. The solution proposed was for City to actively arrange more diagonal connections: specifically, to ensure “three or more players align diagonally”in the central and half-space regions 24,25 .Byhaving a triangle or diamond of players at different heights slicing through Arsenal’s shape, City would create the conditions for quick one-twos and wall passes that could break the defensive lines 26. The article gave an example (with a diagram) of City forming such a diagonal trio in the right half-space: one player near the line, one slightly deeper central, one higher between the lines. Once they did this, the “one-twos and dummied passes” became possible, as the defenders had to cover multiple angles simultaneously 26. In short, the lack of diagonal structure made City predictable, and adding a diagonal alignment restored their ability to combine in tight spaces.

We can visualize a generic structural principle: for every line-breaking pass, have a diagonal support option nearby. For instance, when a striker drops vertically to receive a pass between the lines, a midfielder should position diagonally off him – not directly behind in the same vertical line (where one defender could mark both), and not flat horizontal (where the passing lane can be closed easily), but at an angle. That way, if the striker is under pressure facing away from goal, he can one-touch lay the ball diagonally off to the midfielder who is running onto it facing forward. This “wall pass” or third-man concept only works if the supporting player’s position is diagonal enough to be open yet close enough to combine. Many training exercises enforce this by creating diamonds or triangles in positional drills, basically hard-coding diagonality into structure. The famous “rondo” exercises, for example, typically feature a shape where potential passes are available diagonally through the grid of defenders – never just straight through the middle of them, which would be unrealistic. All of this underlines that good structure = diagonal options.

Diagonality and Width/Depth Balance

Another structural aspect to consider is how diagonality relates to the use of width and depth. Traditional coaching talks about providing “width and depth” in attack – players stretching the field horizontally (wingers on the touchlines) and vertically (strikers pushing the last line back). Diagonality does not contradict this; rather, it refines it. A team that uses extreme width (hugging both touchlines) and extreme depth (a player constantly on the offside line) can open the field, but if everyone is purely wide or high, you end up with large voids between those reference points. Diagonal positioning helps fill those voids and connect the width and depth.

Think of a classic scenario: a winger is hugging the left touchline to provide width, and a striker is pinning the center-backs high. If those two stay on those straight lines, the distance between them might be too large to connect directly. But if the striker intelligently drifts diagonally toward the winger (not all the way out, just into the channel), and simultaneously a midfielder slides diagonally up from the center toward that left half-space, they form a diagonal chain that links the wide player to the center. The winger can pass inside to the half-space midfielder (diagonal inwards), who can then combine with the striker making a diagonal check toward the ball. Now width and depth have been bridged by diagonal structure. This is precisely what many teams do when they “overload” one side: they don’t place three players in a straight line out wide; instead one is wide, one is half-space, one is slightly deeper or higher – forming a tight triangle that can play quick combinations. Once they break through or draw defenders in, they often finish with a diagonal switch to the far side where the opposite winger (who stayed wide) arrives unmarked.

A historical masterclass in balancing width, depth and diagonality was the Brazil 1970 World Cup team (to dip very far back in time). They fielded a fluid 4-2-4/4-3-3 where Pelé played as a withdrawn forward (kind of a 10), Jairzinho and Rivelino as wide forwards. Pelé’s presence meant Brazil often attacked with a triangular frontline: Pelé a bit deeper centrally, Jairzinho high on the right wing, and Tostão (the striker) slightly left of center. The passes between them were frequently diagonal: Pelé would slip Jairzinho in with diagonal through-balls from center to right, or Jairzinho would cut inside diagonally to combine with Pelé. Meanwhile, Rivelino on the left stayed wide and high, but Gerson (midfielder) would drift leftward at an intermediate depth. This created a diagonal link from Gerson to Rivelino to Pelé. The upshot was that even with enormous width (wingers on each touchline), Brazil’s shape always had connectors at diagonal angles, so the ball could funnel from wide to middle seamlessly.

Fast-forward to today’s club game: consider a team like 2023–24 Arsenal under Mikel Arteta. Arsenal often build up in a 2-3-5 or 3-2-5, with five attackers on the last line – seemingly very “flat” in depth. But in practice, those five are staggered: for instance, Gabriel Jesus (striker) might drop off the front line a bit, Martin Ødegaard (right attacking mid) pushes higher between full-back and center-back, Bukayo Saka stays wider on the right but not as high, and on the left Gabriel Martinelli stays very high and wide while Granit Xhaka (left attacking mid) sits a bit deeper inside. The result is a criss-cross of diagonal passing possibilities. Ødegaard and Saka can combine diagonally on one side; Jesus can play one-twos diagonally with Ødegaard or Xhaka; Xhaka can diagonal switch to Martinelli, etc. This demonstrates how even when a formation diagram might show a line of five attackers, the functional structure is layered diagonally.

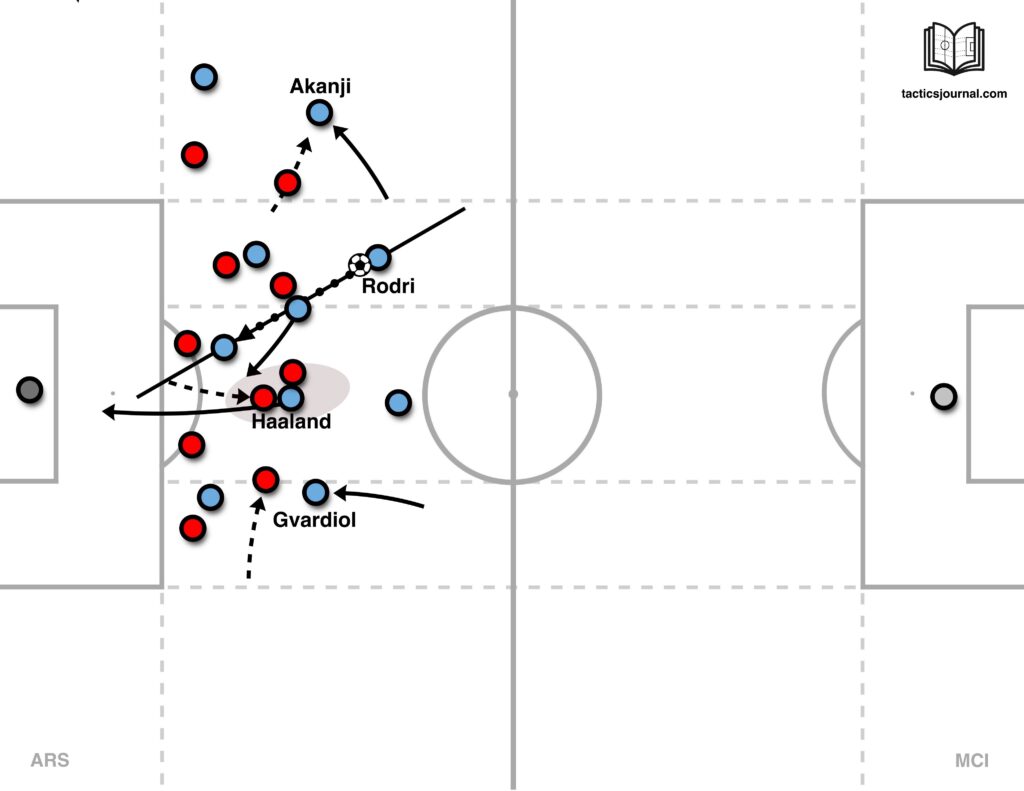

Contemporary Example Diagram: Diagonal Alignment to Break a Block

Conceptual diagram: Manchester City organizing diagonal structures against a deep 4-4-1-1 block (blue = attacking team, red = defending team). By aligning players on different vertical and horizontal lines (e.g. one player dropping off the forward line, one at the last line, one between midfielders, etc.), the attacking team creates multiple diagonal passing triangles through the defensive shape. In this illustration, City’s right-side center-back (Rodri, in a hybrid role) has dribbled slightly forward, drawing pressure, while Haaland (striker) has dropped diagonally toward the ball and Gvardiol (left center-back) has stepped up into midfield on the other side. These movements form a diagonal chain (black dashed line) that opens a lane to feed Haaland and sets up a layoff combination into the space behind (red shaded area). Such staggered positioning makes one-touch combinations and “wall passes” possible, even against a low block 26 27 . Without this diagonal alignment, the attacking options would be isolated and easier to defend.

The above conceptual diagram (inspired by an actual City vs Arsenal tactical scenario in 2024) highlights how deliberate diagonal staggering in structure can unlock a compact defense. Notice how the blue attackers are not aligned flat: one (Akanji) is a bit higher on the right, one (Haaland) drops between lines centrally, another (Gvardiol) pushes up from the left side. The black diagonal lines between them show potential passes. Arsenal’s red defenders, set in two banks, find it hard to cover all these angles – marking one blue player leaves a gap to another. The result is the creation of a diagonal passing lane into the striker (Haaland) and then a quick combination out to the left. This mirrors City’s real emphasis that to break a defensive wall, you often need to “organize those diagonals” in your structure 25 .

Crucially, diagonal structure is not just about offense; it also provides defensive stability in possession (rest defense). If your team is arranged in connected diagonal layers, when you lose the ball you have immediate cover and access to counter-press. For example, if a full-back is pushed very high and wide (pure width) with no diagonal support inside him, a turnover can leave a gaping hole for the opponent. But if there’s a midfielder diagonally tucked inside behind that full-back, a loss of possession is less disastrous – that midfielder can instantly move to counter-press or at least slow the counter. In this way, a staggered shape serves two masters: attacking potency and defensive insurance.

In summary, an optimal team structure weaves a web of diagonal links across the pitch. Coaches design drills and positional maps to foster this, often literally telling players to take up positions “between” opposition lines (vertically) and “inside” or “outside” certain opposing players (horizontally) – effectively coaching diagonal positioning. The best structures appear to have players at different heights and in different channels such that from any given point, there are diagonal options to progress the ball. When you see a team whose moves look improvisational yet synchronized – those beautiful quick passing sequences in tight spaces – you can be sure that the underlying shape was giving those players the necessary angles and support. It’s controlled chaos via diagonality.

Historical Antecedents and Modern Evolution

Having examined the theoretical aspects of diagonality, it’s worthwhile to place these ideas in historical context and see how they’ve evolved into today’s game. While modern analytics and terminology have sharpened our understanding, coaches intuitively leveraged diagonality long before it was a buzzword. And in recent years (2023–2025), we’ve seen an even greater sophistication in how top teams employ diagonal principles.

Early Pioneers: If we reach back in history, diagonal concepts were often discussed in different terms. Hugo Meisl’s 1930s Austrian “Wunderteam” was famed for its passing style – accounts describe rapid combinations and switches of play that likely included plenty of diagonal balls (though the term wasn’t explicitly used). The great Hungarian side of the 1950s (the Magical Magyars) also exploited diagonal movements by withdrawing their striker Nándor Hidegkuti as a deep-lying forward – this created diagonal passing lanes between Hidegkuti and the wingers cutting inside. Perhaps the first explicit articulation of a diagonal system came from Viktor Maslov in the 1960s: Maslov’s 4-4-2 at Dynamo Kyiv had wingers who tucked into midfield when defending and then ran diagonally out-to-in when attacking, a forerunner of the modern inverted winger. Maslov’s teams also made use of diagonal long balls to quickly advance into space when the opponent’s shape was tilted – a counter-attacking principle we recognize today.

The term “diagonal” itself in tactical literature appears prominently with Arrigo Sacchi, as we touched on. Sacchi emphasized that his defensive line should always have a diagonal orientation to the ball – if the ball was on the opponent’s left wing, Sacchi’s right-back would tuck in diagonally behind the line, etc. Offensively, Sacchi’s playbooks (famously detailed sketches) show lots of diagonal arrows: wingers coming inside, midfielders running from deep to wide zones, etc. 28 . In one of Sacchi’s practice drills he’d shout for players to switch positions in attack with diagonal exchanges – for example, the left winger and the second striker might swap via crossing paths, one going diagonal to the wing, the other diagonal into the center. Sacchi might not have used the term “diagonality” in writing, but he understood that a dynamic offense must break away from linear movements. His Milan and Italy sides of late ’80s/early ’90s scored many goals via diagonal through passes – think of Frank Rijkaard’s famous diagonal run and finish in the 1990 European Cup final, or Roberto Baggio’s diagonal dribbles and passes in Italy’s 1994 World Cup run.

Positional Play Revolution: The late 2000s and early 2010s, with the rise of Spanish-style positional play (Juego de Posición) and its German adaptations, saw diagonality reach new theoretical heights. Pep Guardiola’s Barcelona, as mentioned, practically weaponized the half-spaces, which are inherently diagonal lanes. A quote often attributed to Guardiola or his mentors is instructive: “The ball moves faster than any player – especially on a diagonal.” Under Pep, teams learned to move defenses side-to-side and then strike diagonally through the seams. Xavi Hernández, describing his mindset, said he looked not just for vertical “through” balls, but for diagonal passes that connected with a teammate’s run in behind the full-back – because that pass both beat the offside line and changed the point of attack. Guardiola’s Bayern Munich provided a clear example in a 2014 match vs. Roma: Guardiola positioned Arjen Robben as a “free man” on the weak side, and Bayern circulated the ball then hit a long diagonal from the left half-space out to Robben on the right, who attacked directly toward goal 29 30 . That strategy demolished Roma 7-1. Analysts of that time noted how “the value of diagonal play” was that it “attacks through a zone that is usually underloaded by the opponent”, and that it gives the attackers connections to multiple zones (since a diagonal ball from flank to center leaves the receiver able to combine to either side) 31 32 . These insights were heavily influential; they spread through coaching courses and into other teams’ tactics.

In Germany, thinkers like Ralf Rangnick and his school (which influenced Red Bull teams, Jürgen Klopp, etc.) placed huge emphasis on diagonal pressing and passing. One principle in counter-pressing is to force play to a side and then diagonally forward to trap the opponent – essentially using the sideline and a diagonal cover shadow. Meanwhile, in attack, teams like RB Leipzig and RB Salzburg under coaches like Roger Schmidt and later Marco Rose often used diagonal long balls and runs in their quick transitions. A trademark Leipzig goal during the 2016–2017 season was a center-back hitting a diagonal switch over the top to the opposite winger sprinting in behind. Why diagonal? Because a straight ball over the top is easy for a back line to drop and meet, but a diagonal one forces the defense to both drop and shift, often opening a lane between defenders. It’s telling that even the archetype of “direct” vertical football in modern times – say Klopp’s early Dortmund or a Leicester City – actually relies on lots of diagonal passing. Leicester’s Jamie Vardy, for instance, loves to pull toward the left channel and receive diagonals behind the right center-back; many of his famous goals came from Riyad Mahrez or a midfielder sending a diagonal ball that Vardy could run onto at an angle.

2023–2025 Trends: In the most recent few seasons, we observe teams using diagonality in ever-more sophisticated ways. One trend is the use of inverted full-backs or center-backs stepping into midfield to create diagonal layering (as seen with Manchester City’s John Stones moving into midfield, or Arsenal’s Oleksandr Zinchenko inverting). When these players step up, they often position themselves diagonally from the winger and midfielder, forming new triangles. This is partly why City in 2023 became so fluid – a player like Stones or Akanji would suddenly appear in a diagonal channel between opponent lines, giving Gundogan or De Bruyne an extra diagonal target to bounce passes off.

Another development is how pressing-resistant build-up play leverages diagonal outlet passes. Roberto De Zerbi’s Brighton (2023) became known for “baiting” opponent presses deep and then finding a diagonal laser pass through the lines once an opponent jumped out of position. Brighton’s double pivot midfielders would split wide, luring opponents, then goalkeeper Robert Sánchez or a center-back would zip a ball diagonally into the feet of a forward dropping between the lines. This pattern is essentially using diagonality as a pressure valve and a springboard – once that diagonal pass is broken through the press, Brighton often had the opponent unbalanced and could launch attacks with runners peeling diagonally into space.

We also see more diagonal switching of play in the final third. Instead of the old-school cross from the wing, teams like Real Madrid under Carlo Ancelotti have employed what you might call a diagonal dink: a clipped diagonal ball from, say, the inside-right channel to the left side of the box. Luka Modrić is a master of this – receiving near the right touchline but rather than crossing traditionally, he clips a ball diagonally back toward the top-left of the penalty area, where someone like Vinícius Júnior is arriving. It’s hard to defend because it’s not an aerial cross to contest, and not a simple cut-back – it’s something in between.

Finally, set-piece routines increasingly involve diagonal concepts. Attacking free kicks, for example, might see a player run over the ball diagonally to confuse markers, or see the ball played diagonally out to the edge of the box for a volley (a popular routine: a lateral free kick delivered diagonally to an onrushing player at the opposite corner of the area). Teams have realized a static defense set up for a straight ball can be undone by a diagonal delivery that comes from an unexpected angle.

In essence, modern tactics have not only embraced diagonality – they have synthesized it with traditional ideas. It’s no longer diagonality versus verticality or width; it’s using diagonal routes to enhance vertical penetration and enable switches of play. The best coaches today use diagonality as the glue between other concepts. You will rarely hear a Pep Guardiola or a Jürgen Klopp explicitly say “we focus on diagonal play” because it’s ingrained and ubiquitous – a given in how they train their team to occupy space and move the ball.

Training Implications: Coaching the Diagonal

For coaches and analysts, the big question is: how to inculcate these diagonal principles on the training ground? It’s one thing to appreciate diagonality in theory; it’s another to see your team execute slick diagonal combinations under pressure. Training diagonality involves designing exercises that encourage players to use those diagonal options and movements until it becomes second nature.

Some practical training approaches include:

1. Positional Rondos and Grid Games: Set up small-sided games where the pitch is divided into grids or zones, and reward diagonal passes between zones. For instance, a 5v5+3 possession drill might only count a point when a pass is played from one corner zone to the opposite diagonal zone (simulating a diagonal switch or split). This forces players to scan for diagonal outlets. Coaches will emphasize body orientation – receiving side-on – and communication so the diagonal option is recognized and used. By constraining regular square passes, you “force” diagonality. Over time players get comfortable with the angles and timing needed.

2. Third-Man Running Drills: Many academies use drills where Player A passes to Player B, who then one-touches to Player C – the classic third-man concept. To build diagonality, configure A, B, C in triangular shapes (not straight lines). For example, Player A at the base, Player B 15 yards ahead to the left, Player C 15 yards ahead to the right – forming a triangle. Now A passes to B (diagonal), B lays off to C (diagonal), and C dribbles or shoots. Rotate roles. This simple pattern teaches players to approach on diagonal support lines and execute quick angled layoffs. You can increase complexity with moving players (e.g. C starts a run when A passes, arriving diagonally to receive B’s layoff). Focus coaching on the weight of pass and the timing of the run – if B’s layoff is too vertical or too horizontal, C will have a harder angle; if C’s run isn’t diagonal, the layoff won’t connect cleanly. Through repetition, players learn the feel of hitting that third-man diagonal combination.

3. Full-Field Pattern Play: Rehearse specific team patterns that utilize diagonal switches and runs. For instance, set up your back four and midfield in shape, and practice a sequence where the right center-back carries forward and plays a diagonal pass into the left attacking midfielder checking between lines; he lays it off to the right back who has burst forward centrally (an inverted run); then that right back immediately plays a diagonal through-ball to the left winger cutting in behind. This scripted pattern – going right-to-left-to-right-to-left diagonally – trains spacing and timing. After running it unopposed, add passive defenders to increase realism. The idea is not that the team will perform this exact sequence in a game like robots, but that they build a mental library of diagonal combinations. So when a similar spacing appears in a match, players subconsciously recognize: “aha, the diagonal switch then layoff then diagonal through-ball is on.”

4. Conditioned Scrimmages Emphasizing Half-Spaces: Design training games with goals or bonus points for using the half-spaces (the channels just inside the wings). For example, a condition might be: a goal counts double if the attacking move includes a pass from the half-space to the central zone or vice versa. This naturally encourages diagonal passing (since half-space to center is a diagonal relationship) 33 . Or you can mark out triangular target areas around the top of the box where you want players to combine (simulating the classic diagonal one-two zone at the edge of a defense). By rewarding these actions, players are incentivized to look for diagonal entries instead of always going wide or taking low-percentage vertical shots.

5. Video Analysis and Shadow Play: On the cognitive side, use video sessions to point out instances in matches (or training footage) where a diagonal option was available but missed, or where it was used to good effect. Highlight how a player’s movement created a diagonal lane or how a slight stagger in positioning opened a diagonal pass. Complement this with shadow play – walk through tactical diagrams on the field, moving players as if they’re chess pieces, to illustrate diagonal lines of pass and cover. Many players respond well when they visually and physically grasp the spacing; they might literally say “I see it now – if I stand here instead of there, the diagonal pass from the center-back to me is on.” These eureka moments are crucial in translating theory to execution.

From a young age, players can be coached in the habit of checking their shoulder and opening up on the half-turn to be ready for diagonal balls. Small details like receiving with the furthest foot from the passer often mean the body is oriented diagonally, not flat – a simple technical tip that yields better diagonal play. Even finishing drills can involve diagonality: practice diagonal runs onto through-balls and finishing across the keeper (a typical diagonal shot).

Coaches should also tie diagonality to their overall philosophy so players understand why they are doing it. For instance, if you espouse positional play, explain that diagonal passes “eliminate opponents” and find the free man better 3 . If you are a transition-focused coach, stress that the fastest route from winning the ball to a scoring chance is often a diagonal pass to the opposite side of the pitch, catching the opponent off balance. By linking it to the team’s identity, players buy in. They stop seeing diagonal runs or passes as risky or fancy options and start seeing them as the standard of how your team operates.

One challenge is that diagonal passes can sometimes be harder to execute technically (the angles are tricky, and weight must be precise). So drills should not neglect the nitty-gritty: passing technique (hitting that 30-meter diagonal switch accurately), first touch on a diagonal ball (which might have spin or come across your body), and communication (since diagonal passes often go through crowded areas, a shout or signal from the receiver helps). Training with different types of balls – driven passes, lofted diagonals, outside-of-foot curled balls – can build a repertoire. Top players like Kevin De Bruyne or Trent Alexander-Arnold have an arsenal of diagonal delivery techniques (inside bend, outside bend, low skimmer, chipped) that they’ve clearly honed in training.

Finally, fitness and spacing: diagonal sprints can be more demanding than straight sprints because they involve changes of direction and longer total distance. Conditioning drills can include diagonal runs to ensure players can perform these at speed in the 85th minute. And coaches must ensure the team’s overall spacing is conducive to diagonal play – if players are too bunched or too flat, even the best training won’t yield results on matchday. Thus, constant feedback during 11v11 sessions about keeping the stagger, maintaining diagonal support distances (10-15 yards between lines, etc.) is necessary.

The Philosophical Angle (Pun Intended)

Beyond the X’s and O’s, there’s something almost philosophical about diagonality in football. It represents a way of thinking about the game that values creativity, connection, and the exploitation of hidden spaces over rigid, straightforward approaches. If vertical play is about power and directness, and horizontal play about patience and control, then diagonal play is about ingenuity and fluidity – finding pathways that aren’t immediately obvious, and doing so in a flow that unbalances the opponent.

Some modern thinkers have even romanticized the diagonal as the embodiment of football’s artistry. In a recent tactical manifesto, analyst Jamie Hamilton described diagonal passes as “forging transversal routes that resist the logic of linear progression”, carving out moments where play “breaks free from its cartographic chains” of structure 34 . In his view, a well-timed diagonal ball carries a almost rebellious quality – “deterritorializing” the opponent’s defensive order and creating a “space of potentialities” where something unexpected can happen 34 . When you see a diagonal pass split a defense and lead to a goal, it indeed often feels like a sudden jailbreak from the established pattern of play – a moment of improvisational genius even if it was pre-conceived in training.

The diagonal, in a sense, marries the strategic and the improvised. It is a calculated geometry, but also the angle of spontaneity. Johan Cruyff once said that players should “use every side of a defender” – not just try to go through or around, but sometimes use the opponent’s body as a kind of reference to play off. A diagonal mindset embodies that idea: you’re not confronting the opponent head-on, you’re using angles, you’re being clever.

Philosophically, diagonality also underscores the relational aspect of football. It’s often said that football is a game of relationships – between players, between spaces. Diagonal play emphasizes relationships over positions. Two players can be linearly far apart positionally, but if they share a diagonal connection in the moment, they are effectively close in footballing terms. A diagonal pass is a conversation between the passer and receiver that bypasses others who aren’t part of that conversation. This aligns with the concept of relationism in tactical theory (as opposed to rigid positionism). Instead of players occupying fixed spots and passing only when “the system” dictates, relationism allows players to interact dynamically – and diagonals are the threads of that dynamic interaction, cutting across the static grid.

When players truly grasp this, the team starts to play “in between” – in between opponent lines, in between traditional patterns, and even in between the past and future (because a good diagonal can almost seem to come from the future, catching everyone by surprise). It brings a sort of rhythm to the game that is less predictable and more difficult to defend. Opponents often describe facing such teams as feeling like “we never knew where the next attack was coming from”. That’s exactly the effect of multifaceted diagonal play: it’s like punches coming from odd angles in boxing – the ones that knock you out aren’t the straight jabs you saw coming, but the uppercuts and hooks from the side.

On a lighter note, diagonality also gives football much of its aesthetic beauty. A long diagonal switch that arcs across the field to the opposite flank, or a slide-rule diagonal pass that bisects defenders, are among the most visually satisfying sights in the sport. They appeal to our sense of geometry and surprise. Even neutrals will often “oooh” at a well-hit diagonal ball that opens the game. There’s a reason highlight reels love the cross-field pass that changes the play – it carries a dramatic shift in perspective, much like a plot twist in a story.

Conclusion: The Diagonal Perspective

In “diagonality,” we find a principle that is both timeless and ever-evolving. It is rooted in the simple geometry of the pitch – 360 degrees of possibilities – and yet it continually yields new tactical innovations as the game’s collective understanding deepens. For advanced coaches and analysts, cultivating a diagonal perspective means training your eye (and your team) to always seek those hidden angles: the pass that splits multiple lines, the run that appears in someone’s blind side, the structural tweak that creates an extra triangle of connections.

We’ve seen how diagonal passing combines the best of vertical and horizontal play – gaining ground while unbalancing the opponent 2 . We’ve detailed how diagonal movements, both off the ball and on it, create space and confusion by forcing defenders into awkward, lengthy adjustments 6 16 . We’ve illustrated how entire team structures can be built on diagonal relationships, yielding a network of constant support and threat across the pitch 22 26 .Historical and contemporary examples alike affirm that success at the highest level often hinges on intelligent use of diagonal principles – from Sacchi’s organized chaos to Guardiola’s positional weave to the latest tactical experiments of 2025.

In practical terms, the takeaway for coaches is clear: teach it, shape it, rehearse it. Insist on staggered positioning; freeze a training play when players line up flat and ask, “who can give a better angle?” Celebrate the goals that come from a diagonal pass or run in film sessions to reinforce their value. Over time, a team that might initially only see straight lines can develop a kind of diagonal vision, identifying and exploiting the subtle lanes that opponents leave open.

There is also a broader lesson here about creativity and problem-solving. Football, like many complex systems, often rewards those who think laterally – or in this case, diagonally. When a direct route is closed and a simple lateral pass is safe but toothless, the answer is usually a clever diagonal that breaks the equilibrium. Training players to recognize that is training them to be inventors on the field, not just executors. This is perhaps the ultimate mark of a mature tactical system: when players instinctively fill the diagonal gaps and find the diagonal solutions without over-relying on rote instructions.

In closing, consider the diagonal not merely as a type of pass or run, but as a philosophy of play. It is the understanding that football is not played on a linear grid, but on a continuum of angles and connections. It’s a reminder that effective play is often about connecting the opposites – merging width with depth, combining control with penetration, binding method with spontaneity. The diagonal is the line that joins two points in a fresh way. As coaches or analysts, if we can instill that mindset, we give our teams a powerful tool: the ability to find or create an advantage where others see none.

In the ever-evolving chess match of football tactics, diagonality remains a constant secret weapon – a way to move pieces that catch the opponent off guard. Master it, and your team will not only be harder to defend; it will play a brand of football that is fluid, dynamic, and a joy to watch. And as any disciple of the game’s great thinkers will tell you, when theory and beauty converge on the pitch, you know you’ve found something special – something as simple as two points connected by a well-weighted pass, and as complex as the myriad possibilities that pass unlocks. That is the power of the diagonal.

Sources:

1 2 6 7 9 10 13 14 16 17 33 » The Half-Spaces https://spielverlagerung.com/2014/09/16/the-half-spaces/

3 4 5 11 29 30 31 32 » Juego de Posición under Pep Guardiola https://spielverlagerung.com/2014/12/25/juego-de-posicion-under-pep-guardiola/

8 12 22 » Team Analysis: Napoli https://spielverlagerung.com/2016/04/08/team-analysis-napoli/

15 28 » Arrigo Sacchi’s cultural revolution https://spielverlagerung.com/2016/01/01/arrigo-sacchis-cultural-revolution/

18 Coaches’ Voice | World Cup final 2022 tactical analysis: Argentina 3 France 3(4-2 on pens) https://learning.coachesvoice.com/cv/world-cup-final-2022-tactics-argentina-messi-france-mbappe/

19 20 » City in control to beat Crystal Palace https://spielverlagerung.com/2019/04/16/city-in-control-to-beat-crystal-palace/

21 Importance of the Triangle – Grassroots Football UK https://www.grassrootsfootballuk.com/importance-of-the-triangle/

23 24 25 26 27 How Manchester City should break down Arsenal’s low block on the diagonal – Tactics Journal https://tacticsjournal.com/2024/09/22/how-manchester-city-should-break-down-arsenals-low-block-on-the-diagonal/

34 THE DIAGONALIST MANIFESTO. Vectorial Relationism & The Liberation… | by Jamie Hamilton | May, 2025 | Medium

https://medium.com/@stirlingj1982/the-diagonalist-manifesto-610bf3fbca15

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen