Organized Chaos: Bournemouth’s Possession Principles Against Nottingham – MH

On Matchday 23, the two surprise teams of the Premier League faced off. Nottingham, unbeaten in their last nine matches, has impressed this season with outstanding defensive work. Bournemouth, coached by Andoni Iraola and now unbeaten in 12 games, takes a completely different tactical approach compared to most other teams. In an interview with TNT Sports, Guardiola remarked: “Today, modern football is the way Bournemouth, Newcastle, Brighton, and Liverpool play.” What exactly are these teams doing differently? Bournemouth’s approach will be analyzed in detail based on this match.

The Importance of the Match

Bournemouth’s coach, Andoni Iraola, is a former player under Marcelo Bielsa at Athletic Bilbao. Bielsa, widely known in the Premier League as the coach who led Leeds United to promotion, gained recognition for his style of play characterized by exceptionally high intensity in all phases of the game. According to Iraola, his own footballing philosophy has been significantly shaped by his former coach Bielsa.

In an interview with Sky, back when he was still managing Rayo Vallecano, Iraola stated: “I was very lucky to play for him (Bielsa) for two seasons as a player. I think he has another vision of football. They were two very good seasons for us, and, for me, it was a different knowledge.” He also explained: “I use a lot of exercises from Marcelo that I learned from him. I use a lot of things, especially with the ball. Offensively, his teams are very dynamic. He is willing to make all the runs to the space, he is ready to accept this kind of disorder, offensively.”

Iraola’s tactical concept can be described as “organized chaos.” The aim is not to implement a positional system with perfect patterns of play. Instead, the focus is on creating problems for opposing teams by generating chaos. The idea is to force the opponent into unfamiliar, uncontrolled phases of play. A particularly important concept within this is highly intense, man-oriented, hybrid attacking pressing, designed to force the opponent into quick turnovers and a fast-paced, direct game.

„It is true that we like, and we perform better, in high-tempo games. We need to run a lot. We don’t need so much control, not in every single play, but I think we have the legs, we have the willingness, to go up and down.“ – Iraola

Accordingly, Iraola’s style of play could face challenges against deep-lying teams that deliberately thrive on minimal possession. These teams don’t need to engage with Bournemouth’s high-intensity game but can instead remain compact out of possession. They are not required to build up play from the back under Bournemouth’s pressing to maintain controlled possession but can focus on their own offensive transitions. This season, Nottingham has been one of the most successful teams in executing such an approach. Consequently, it was particularly intriguing to observe how Iraola’s Bournemouth would operate in possession against Nottingham’s deep block.

Bournemouth in Possession

Iraola describes his philosophy in possession as follows:

“We have to prepare [positional] patterns, but we cannot just prioritise them. If you can see that you don’t have a teammate ahead, forget about the pattern, just drive the ball and try to force things to happen. I want him to attack first.”

Here lies the challenge I encountered while analyzing the game against Nottingham: how do you describe intentionally provoked chaos, where there are barely any fixed patterns? Only a few predefined sequences can be identified within the positional framework. The crucial question, therefore, is: what reference points structure Bournemouth’s possession play, and which principles of play create this chaos? Or, put simply: what “tools” does Iraola use in his style of play? To answer this, the positional framework of the game against Nottingham will first be examined.

Starting from a nominal 4-2-3-1 formation, Nottingham defended out of possession in a 4-4-1-1 or 4-5-1 structure. Nottingham focused primarily on defending and largely conceded possession to Bournemouth, a characteristic approach for the team. Under coach Simoes Espirito Santo, Nottingham has averaged just 40% possession this season.

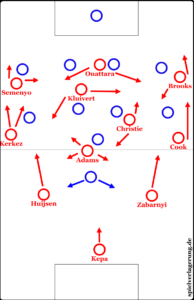

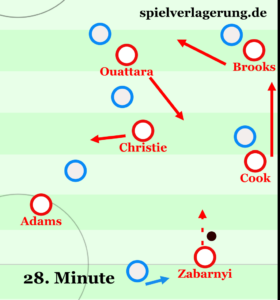

Bournemouth, meanwhile, operated in possession with a positional 2-4-4 or 2-3-2-3 structure, featuring wide wingers and full-backs. From this setup, Bournemouth attempted to break through Nottingham’s deep block. On the (left) No. 10 position, Kluivert stood out with his exceptional dribbling ability and high agility. Central midfielder Christie alternated between the deeper right half-space as a right-sided No. 10 and the No. 6 position.

Nottingham was often forced back into their own half from an initially higher defensive pressing. When Nottingham attempted to press higher, Bournemouth’s center-backs positioned themselves wide, and goalkeeper Kepa moved up to form part of the back line. This made it nearly impossible for Nottingham’s lone striker to put significant pressure on the ball carrier. As a result, Nottingham dropped deep, retreated, and refrained from pressing the ball-carrying center-backs.

Vertical Play

„I sometimes value much more a player carrying the ball and forcing things to happen. I think when you play too positional – one, two touches to find a free man – you sometimes lose the initiative from the players to just take their man on and attack the spaces.” – Iraola

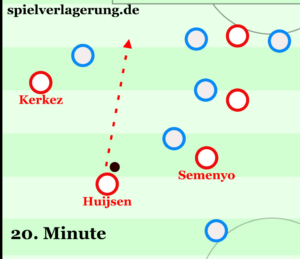

This approach meant that Bournemouth’s center-backs were frequently required to dribble forward against stationary opponents, forcing defenders to commit. This often created 5v4 or 4v4 situations on the flanks, caused by the strong lateral movements of striker Ouattara and attacking midfielder Kluivert, combined with the forward dribbling of the center-backs. When no passingoptions were available, the team didn’t rebuild play, as is typical for positionally oriented teams. Instead, Bournemouth’s left center-back, Huijsen, was occasionally seen dribbling directly at the opponent’s last defensive line. It can be concluded that one of Iraola’s key principles of play is to attack vertically with the ball as early as possible.

Center-back Huijsen dribbles toward the final defensive line himself due to a lack of better-positioned deeper passing options.

The situations on the flanks during the center-back’s dribbling were played out in various ways. Sometimes the ball was passed to the wide player on the wing, who was tasked with taking on a 1v1 duel. This player was consistently supported by the full-back in a dual-width setup.

Particularly noteworthy were the positional rotations of the 3-4 players on the flanks. Full-backs, attacking midfielder Kluivert, striker Ouattara, and the winger frequently rotated out of their positions, occupying different spaces. What stood out was the consistent presence of a dynamic deep run within these rotations, forcing the opponent to cover the run and thereby creating space between their players.

For example, the left-back Kerkez, during the center-back’s dribble, occasionally made deep runs into the half-space. Similarly, attacking midfielder Kluivert was often involved, sometimes shifting laterally to receive the ball and then driving forward at pace to attack the defensive block.

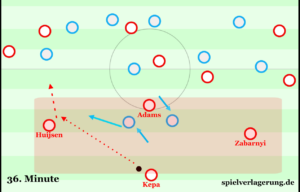

Nottingham responded to this from the 30th minute by attempting to apply more pressure on Bournemouth’s ball-carrying center-backs. The 4-4-1-1 shape was adjusted by removing the man-marking on defensive midfielder Adams. Instead, Nottingham transitioned into a 4-4-2 setup, aiming to position Adams in the cover shadow and step out earlier to press the center-backs. However, Bournemouth’s goalkeeper Kepa played so high in the back line that he was still able to connect with the now even wider-positioned center-backs, allowing them to continue dribbling forward.

The goalkeeper stepping into the back line creates a 4v2 situation, allowing the center-backs to dribble forward with less pressure from opponents.

The Magic of Dribbling

“I would say they have the freedom to risk a little bit in the dribbles.“ – Iraola

Another key principle of Bournemouth’s possession game is diagonal, vertical dribbling. These serve as a chaos factor and are constantly utilized across all positions. As long as no teammate is better positioned toward the opponent’s goal, players are given the freedom to dribble. The skillful dribblers on the wings, the striker, and attacking midfielder Kluivert fit perfectly into this principle. The spaces opened up through the aforementioned rotations, particularly between the opposing players on the flanks, were mostly attacked through dribbling rather than passing.

The core idea behind this focus on dribbling is closely aligned with the concept of relationism. The goal is to make the team’s decisions less predictable for the opponent and to create a certain degree of chaos. Traditional positional play often limits players’ individual freedom, which reduces the element of surprise. However, Iraola’s execution of possession football differs significantly from relationism.

Instead of using a tighter structure to encourage combinations between players, rotations and larger distances between players are used to create spaces intended to be attacked through dribbling. It is crucial that these dribbles are always executed as vertical actions, continually putting the opponent under defensive pressure and thereby opening up other options.

Box Occupation

Due to the larger spaces on the flanks, many dribbles are initiated on the wing, supported by the dual-width occupation of the winger and full-back. To enforce a successful follow-up action against deep-lying opponents, proper box occupation is a fundamental requirement. Iraola’s teams often flood the opponent’s penalty area with up to seven players, forcing the opposition right in front of their own goal. The goal is not necessarily to find the open player but to increase the likelihood of winning the ball after a cross in the penalty area. Second balls also play a significant role in this approach.

Counter-Pressing and Rest Defense

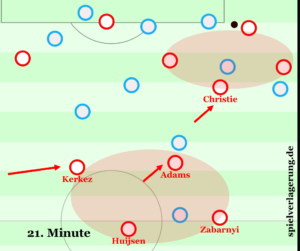

Risky dribbles have the additional advantage of provoking more frequent transition moments. When the opponent tries to transition offensively, they lose their compact defensive shape. Bournemouth’s flexible rest defense allows the ball to be immediately recovered after a loss of possession. Bournemouth’s rest defense typically consists of 3-4 players, depending on the attacking structure. In addition to the two center-backs, defensive midfielder Adams and the inverted, far-side full-back provide cover. If both full-backs or Adams are involved in the attack, Christie drops deeper to provide support and shifts closer to the ball.

On one hand, it’s important to highlight the excellent sense of positioning from the two central midfielders, Adams and Christie, in anticipating potential turnovers. Their ability to read these moments and their spatial awareness lead to many successful counter-pressing actions. On the other hand, the immediate pressure applied to the ball-carrying opponent after a turnover is notable, leaving the opposition with little opportunity to create controlled possession phases.

As a result, Nottingham’s offensive presence in the first half was minimal. Successful offensive transitions by Simoes Espirito Santo’s team were extremely rare.

The rest-defense structure in the 21st minute consists of the inverted Kerkez, the shifting defensive midfielder Adams, and the center-backs. At the same time, the ball-near teammates position themselves in response to the dribble in a way that allows them to immediately apply pressure if needed.

Offensive Transitions

Another key principle of Bournemouth’s play is that after regaining possession, the first action is immediately directed forward. In contrast to traditionally positional teams, control is not sought through possession in chaotic situations but rather through constant transitions. The goal is to prevent the opponent from regaining their structure and settling into their usual rhythm. This creates intense pressure for Bournemouth’s opponents. As a result, Bournemouth often didn’t even need to break down Nottingham’s defensive block because the opponent never had the chance to regain their typical structure.

After recovering the ball, Bournemouth consistently looked to play forward into pressure. When positioned deeper (closer to their own goal), players in the forward zones immediately made runs into space to create vertical passing options. Even if the Bournemouth player who regained the ball was immediately under pressure, the first action was directed forward.

If necessary, a long ball was played toward the opponent’s defensive line, with a focus on winning second balls. This pressing game with an emphasis on second balls—often referred to as “kick and rush”—generated additional forced transition situations, preventing the opponent from finding their usual shape. The fact that four of Bournemouth’s five goals against the typically deep-lying Nottingham team came from deliberately provoked transition moments highlights the effectiveness of this approach.

Nottingham’s Attacking Press

In the second half, Nottingham switched to an attacking press in an attempt to create more scoring opportunities and overturn the 1-0 deficit. However, Nottingham was unable to pin Bournemouth in their own half as planned. Instead, Bournemouth played targeted long balls to one of their four advanced attackers or to the half-high positioned full-backs. Through a combination of winning second balls, dribbles, and central midfielders following up for lay-offs, Bournemouth was able to quickly progress into space and control the game from their own half. This led to Bournemouth scoring their second and third goals in quick succession. The final result was a resounding 5-0 victory for Iraola’s side.

The Chaos

So, what exactly causes the chaos in Bournemouth’s possession play? In summary, it is a combination of the principles discussed: playing vertically as early as possible; dribbling diagonally and vertically as long as no player is better positioned toward the opponent’s goal; and making the first action after regaining possession a forward one. The focus on vertical zones (reference point: opponent players) and second balls (reference point: the opponent’s goal) creates an intense and dynamic style of play that prevents the opponent from settling into their usual structure. Bournemouth is further aided by their attacking press, which was not analyzed in detail in this article but consistently provokes additional transition situations.

What can other teams take away from Bournemouth’s possession approach without abandoning their own philosophy? One lesson is the courage to consistently seek depth, provided the team has appropriate counter-pressing structures in place. Additionally, the dynamism of individual actions at Bournemouth is remarkable. Rarely have I seen such explosive runs into depth from other teams.

Conclusion

The final question is: what do the teams mentioned by Guardiola in the aforementioned interview have in common? All of them attack the depth quickly and frequently, making the game incredibly dynamic and intense. This forces the opponent to make decisions faster. After all, the main difference between good and very good players is the time it takes to make a good decision.

My recommendation is to watch games from 30 years ago. It quickly becomes apparent that football has become faster and more demanding.

“For me, the players are better than in 2003. They have to do the same things, but much faster. The physical demands are ridiculous. I doubt I could have played at this rhythm.” – Iraola

Author: MH is a football aficionado at heart. His apartment resembles a football library, with shelves filled with books on the great tacticians from Rinus Michels to Pep Guardiola. Of course, the book from Spielverlagerung.de is not missing. For MH, football is not just a game, it’s a way of life. He can be found on X under Mh_sv5 and LinkedIn.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen