Tuchel leads PSG to first ever final

Thomas Tuchel’s PSG side faced Nagelsmann’s RB Leipzig in the first Champions league semi-final on Tuesday evening. Whilst both sides came through their quarter-finals with late winners, PSG did so fulfilling their favourites tag with Leipzig instead causing an upset.

PSG’s positional structure

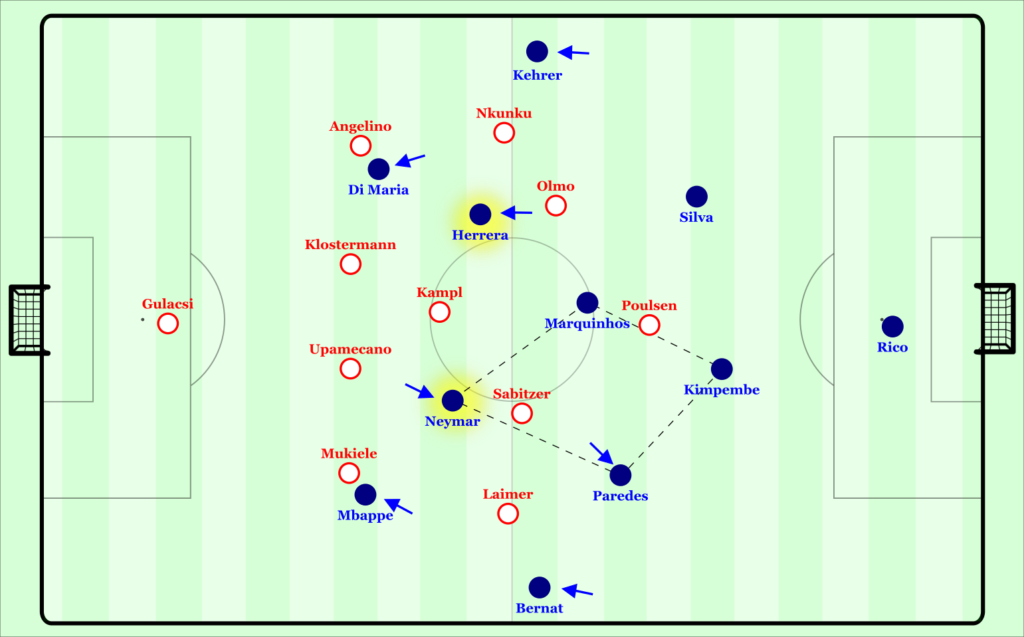

Nagelsmann’s side chose to begin their defensive phases by forming their compact defensive structure, initially leaving their opponents time to build attacks from deep. Most of the first half then became a battle of PSG in possession trying to find ways to break Leipzig’s mid-block structure. From their nominal 4-3-3, PSG moved towards a 4-2-2-2 structure with largely fitting roles for key players. Di Maria and Mbappe as the nominal wingers took high positions against the back line, either pinning from a position between the near centre back and full-back, or on the full-back’s outside shoulder. Neymar dropped from his centre forward position mainly to the left half space between the lines, and was joined on the right by Herrera moving up from his right 8 position. Bernat and Kehrer moved high on their respective flanks, having very little and basic participation in build-up. Instead the Parisians sought to build-up mainly through the centre and half spaces. To that end, Paredes constantly dropped to a deep position in the left half space with Marquinhos as a central 6. With these four deep build-up players, PSG moved between an asymmetric 2-2 and 3-1 shape.

Leipzig’s 4-1-4-1-0

As the highest player, Poulsen mainly positioned himself to block Marquinhos’ participation in build-up through his cover shadow. Without a central 10 in their structure, the central 6 space was naturally a potential weak spot in their pressing, thus the Danish striker’s role was key. The Parisian build-up would now be led towards the half spaces, the responsibility of Leipzig’s 8s. Sabitzer and Olmo had to combine blocking the space behind them where Neymar and Herrera lurked, with moving forward to apply pressure on the deeper players in PSG’s structure. They could be seen constantly checking their shoulders and adjusting their position after every pass to ensure they were positioned to block Neymar & Herrera. Sabitzer’s role on the right in particular was key given Paredes held a position in front of him. With Kimpembe dribbling forwards, Sabitzer had to maintain his position as long as possible to prevent reverse passes to Neymar behind him, before pressing at speed to reach Paredes as soon as he received the ball to prevent him turning and facing forwards. Initially he carried this role well causing Tuchel’s side to need switches more often. From here, Olmo made less consistent attempts to press Thiago Silva after long passes from the left.

Poulsen/Marquinhos; the spanner in the works

However, Poulsen made a number of badly timed and individual attempts to press PSG’s centre backs. Through the Dane’s poor timing and pressing direction, Marquinhos was left free and could be easier accessed from Kimpembe or Silva.

When Marquinhos could receive, Kampl had to move from his covering 6 role, and step up to press, again within the theme of preventing the midfielders receiving and facing forwards. As a result, Sabitzer and Olmo had to move narrower to cover the spaces either side of Kampl. Marquinhos could now play to Paredes and Sabitzer now had a deeper and narrower start position to close the Argentinian down from. He was now unable to prevent Paredes from facing forwards, and found it more difficult to block Neymar behind him. Receiving the ball and facing Leipzig’s midfield line, Paredes could use his exceptional disguise ability to open and/or exploit the slightest channels between Leipzig midfield line, mostly finding Neymar in space between the lines.

Whilst Leipzig wanted to prevent this situation, they mostly reacted quite well. By pairing quick backwards pressing from the midfield, and forward defending from the closest member of the defensive line, they created a high pressure area to constrain PSG’s next actions. Whilst they hardly conceded chances from these situations, they gave away a number of free-kicks which further contributed to PSG’s territorial dominance. The Bundesliga outfit’s pressing was more effective when Olmo or Sabitzer sprung forwards to attack long switches towards a centre-back with good timing. From here they they could block the receiver’s route directly forwards and diagonally to the 6 space, Poulsen could then threaten the switch back to the far centre-back. They could then be forced to involve their full-backs earlier who could be isolated against the touchline by Laimer or Nkunku, with the near 8 and Kampl recovering to block passes back infield.

Red Bull’s wings problem

Due to the interaction between the two structures, Leipzig’s wingers had practically no positive function in their mid-block defending phases. They were easily pinned into flat positions in the midfield line by PSG’s high full-backs, thus prevented from contributing to pressing PSG’s central build-up players. Their only pressing contribution was in the rare occasions that Kehrer or Bernat received, but they mostly did so without real access. Whilst Laimer and Nkunku supported their side’s general compactness, they were mostly not close enough to help defend the regions Neymar and Herrera targeted as that would mean being too far infield to press the full-back on their side.

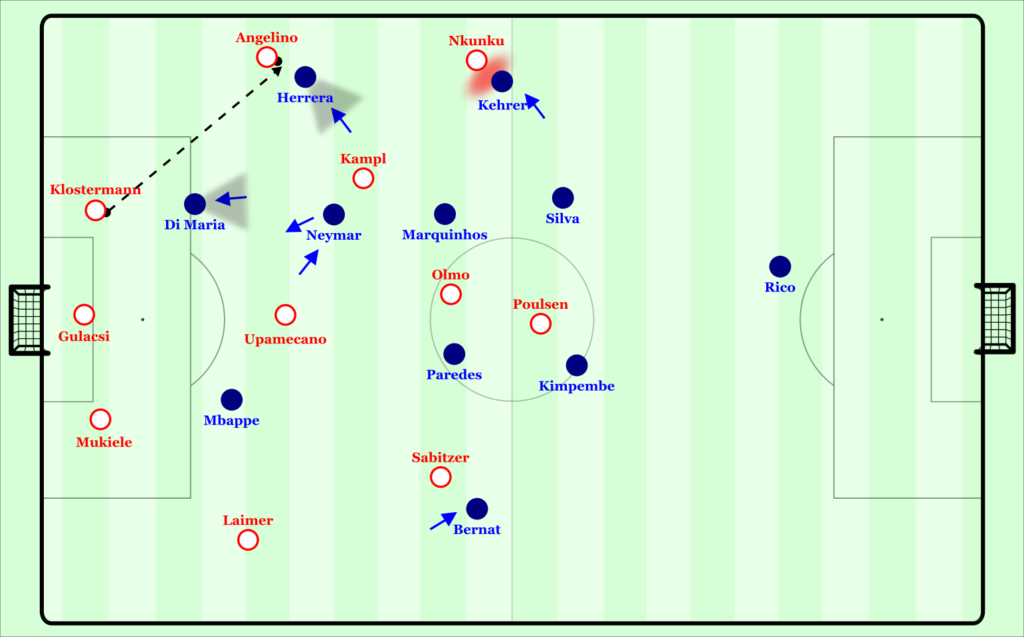

PSG’s goal-kick press

Given their high territorial inferiority, Nagelsmann’s side had a number of goal-kicks from where they faced an aggressive Parisian press. Tuchel’s side began these phases with an extremely narrow front three with the wingers holding positions ready to attack the first pass to Klostermann or Mukiele in a vertical manner. As the central 9, Neymar started from a position directly between Upamecano and Kampl who occupied the 6 space. Bernat held a high position on the left side with Herrera wide on the right, ready to press the Leipzig full-backs.

Through the early and vertical pressure from Di Maria or Mbappe, they could block the half space lane, leaving the wide pass as the logical next option. With no possibility to be outplayed on their inside, Herrera/Bernat could move wide early to close down the wide defender on their side. With the ball moving wide, Neymar would block the near 6 but did well to switch his attention back to the receiver’s central options when the ball carrier’s body position made it clear the near 6 was no longer playable. Most moves thus With bigger and quicker separation movements between the 6s, Leipzig could have taken advantage of the overload they had against Neymar in this position.

Leipzig problems in 3v3

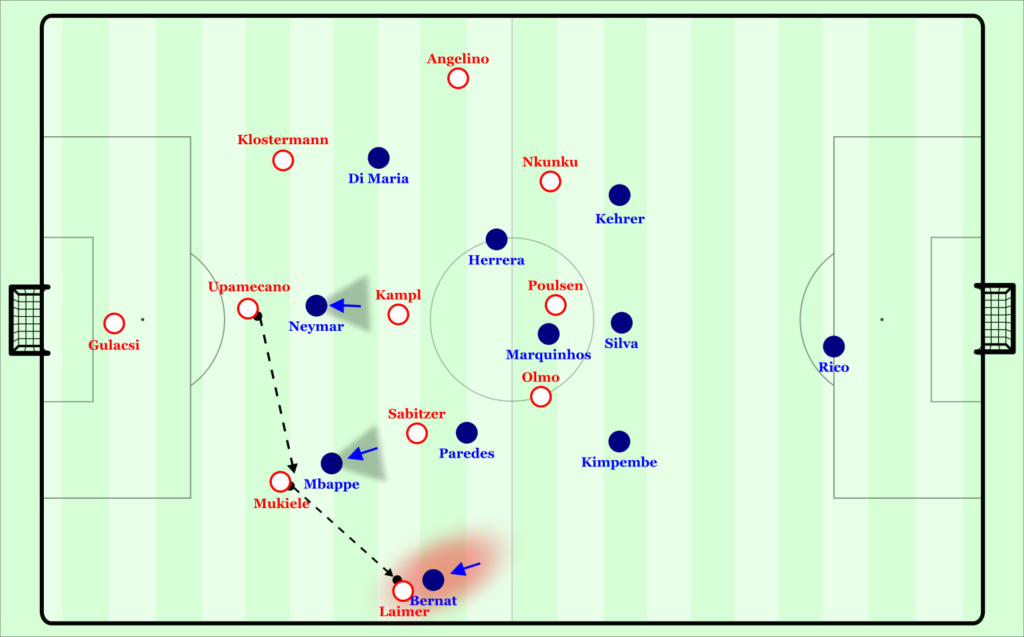

In possession, RB formed a similar structure to their quarter final against Atletico, playing in a 3-1-5-1, with Laimer again moving to a right wing-back position. As opposed to the quarter final, they had big issues to outplay the opponents’ first line of pressure.

With Tuchel’s men pressing in a 4-3-3 shape, the German side faced a 3v3 situation in the first line. With early pressure on each player of their first line, the first touch of each receiving player had to be taken in a direction away from pressure, rather than a way that would keep multiple options open. Thus their first touch restricted the number of playable options they had, and led to a body position which clearly signalled where the next pass would be played. The next pressing player from PSG could then leave their position earlier to attack the next pass. The effect of this early pressure was also felt higher up, with less time for the forwards to get into position to occupy or move into open lanes within the Parisian structure. The result of these phases was often Laimer or Angelino receiving the ball in a deep and wide position under pressure from a PSG full-back, and no clear pass options with ball losses a natural consequence.

To help solve these early build-up issues, Sabitzer often dropped to the 6 space when Upamecano had possession, ideally creating a 2ndoption alongside Kampl to outplay Neymar. Yet this movement gave Paredes a simpler pressing direction, and like Kampl earlier, Sabitzer was without a clear lay-off option given the 3v3 situation in front of him. From here Olmo moved from the central lane towards the right half space to become an option behind Paredes, however the movement and/or pass were usually too late to take advantage. Leipzig also attempted chipped passes to Angelino dropping on the left, but he was mostly closed with good timing by Kehrer and forced to play long line before controlling the ball.

Leipzig’s defensive switch

After around 33 minutes, Nagelsmann’s team moved to a 4-4-1-1/4-4-2 in their mid-block defending. Presumably seeing the positive effect of those moments where Sabitzer/Olmo effectively moved up to help press PSG’s first line, they opted to create this from a more permanent structure. However, with their attempts for earlier access on the first line, Leipzig left the 6 space more exposed. Marquinhos and Paredes now became even more present in early build-up situations, able to switch between themselves and both half spaces easily.

2nd half

Nagelsmann throws the dice

After the interval Leipzig brought Schick and Forsberg on, moving to a more fixed 5-3-2 structure against the ball and an asymmetric 3-1-4-2 in possession.

In possession

Their attempts to outplay PSG’s 4-3-3 differed on the right and left sides. The players in the back 3 remained the same, with the wide centre backs mostly moving deeper and wider when Upamecano had possession in an attempt to open diagonal passing lines further upfield. On the left, Angelino played far deeper than Laimer on the opposite flank, with Forsberg as the left 8 playing higher, and Sabitzer deeper on the right side, dropping to the 6 space as he did previously.

On the left they sought early diagonal passes to Angelino through the channel between Herrera and Di Maria, with Forsberg constantly attacking the space behind Kehrer. Alternately, Angelino could come infield to an 8 position whilst Forsberg moved high and wide to pin Kehrer back. On the right they attempted similar breakthroughs to previously, with Schick moving towards the right half space behind Paredes when he moved to press Sabitzer. From his higher start position, the Czech striker performed this movement slightly quicker than Olmo. The interaction between the two strikers, with their higher start positions, and counter movements to pin the opposing centre backs, and offer an option between the lines worked better to give quicker routes to progress attacks.

In pressing

From their new base 5-3-2, RB pressed higher in a 3-3-2-2 shape before falling into a 5-3-2/5-3-1-1 shape in midfield pressing. Through the two strikers and two 8s, they formed a central box. None of these players immediately attempted to block passes into the 6 space, instead maintaining positions to isolate any potential receiver in this position. After a turnover in this position, PSG played more cautiously, avoiding this position in following situations. The earlier pressure on the Parisian centre backs led to earlier use of Bernat and Kehrer in build-up. These players were then closed down either by the near 8 or wing-back, with the other blocking any opponent in the offensive half space behind them. The far side players moved well to restrict the full-back’s options to play infield. The far striker would move diagonally infield to block the 6 space, whilst the far wing-back would move infield to support the compactness in the midfield line. This movement freed the far 8 to attack any long passes infield, particularly to the far centre-back, with a number of turnovers coming from this movement.

…but still lacking a goal threat

The adjustments to their structures combined with the state of the game led to more territorial dominance for the Germans, but this hardly translated to goal scoring chances. They were unable to translate turnovers to dangerous counters either due to winning the ball back too deep within their structure with several PSG players in deep positions or lacking runners to attack the spaces in PSG’s structure before they could recover. In positional attack phases, they faced a passive Parisian midfield line who preferred to keep short distances to their back line. Leipzig were unable to use this the extra time afforded in front of PSG’s midfield to commit players provoke pressure and combine past them, instead often playing into wide positions early. From here the wing-backs were often isolated on the wings, lacking support for combinations to break through the space created inside PSG’s pressing full-backs. Instead they often played early lofted crosses towards Poulsen and Schick which at times caused confusion, but hardly any chances. The deep positions from Marquinhos and Paredes were key here, in helping the defensive line congest the space for Leipzig’s strikers to attack.

Conclusion

In the end, the overwhelming quality in the PSG ranks proved too much for their German counterparts as they reached the first Champions league final in their history. They will be watching on eagerly as Bayern take on Lyon to discover their opponents in Sunday’s final, with a mouthwatering final against the perennial German champions a likely result.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

MSP August 20, 2020 um 1:11 pm

Fantastic article by the way, i noted in my match preview how paredes operating in the kroos position could help them dismantle Leipzig’s press, and also fantastic work on the observation on sabitzer, at the beginning of the game he was able to have access to paredes with his speed, but he tired out eventually, good work JD, i like your articles, the link to my twitter thread can be found here

https://twitter.com/maga_SP3/status/1295657355883970565?s=20

JD August 25, 2020 um 1:55 pm

Thanks, and good observation on your thread