Leipzig and City’s Contrasting Results Show Importance of Depth Options for In-Possession Strategy

The Champions League quarter finals treated us to some interesting match-ups over the past few days, two being Leipzig’s victory over Atletico Madrid and Lyon’s shock result over Manchester City.

To an extent, both performances in possession can be explained by the importance of depth options to threaten in-behind. This collaborative analysis between MV and JD will explain their role in Leipzig’s in-possession strategy, while the lack of options led to City struggling against Lyon’s 5-3-2.

Effect of Defensive Structures

Of course, it’s only fair when comparing the two performances to account for their opponents’ approach without the ball. Atletico defended in a clear 4-4-2 midfield press whereas Lyon used a 5-3-2, two formations which pose clearly different challenges to the in-possession team.

With an extra man in the last line, the 5-3-2 naturally gives better coverage of options in-behind due to greater cover of the width of the pitch. The extra player means that the line can cover more space horizontally without having too large distances between the defenders. While the midfield line is one less, a well-organised three can still cover the centre quite well while sacrificing wider areas.

While immediate passes in-behind are better covered, having depth options is still crucial but instead more from a purpose of pinning the defenders. By stopping the defenders – particularly the wing-back and wide centre-back – from stepping out, you initially create more time on the ball in wide areas. With the defenders pinned, this extra time then forces the opposition central midfielders to press in wide areas, increasing the opportunity to create space between the lines.

In comparison, a 4-4-2 has less coverage in the last line and thus the spaces in-behind. On this basis, depth options become more important as an option to immediately receive the ball in-behind the defence. With the extra midfielder, teams’ coverage of the movements in-behind typically come from the midfield line, meaning that players between the lines can be important to either

- Stop the midfielders from covering the runs in-behind

- If the midfielders follow the runs in-behind, these central players can occupy any lanes opened up

In both situations, depth options are key to the teams’ in-possession strategy. This analysis will discuss how they were important factors in RB Leipzig’s win, and Manchester City’s loss in the Champions League quarter-finals.

Leipzig Isolate Full-Backs and Attack Depth

Nagelsmann opted for a 3-1-5-1 structure against Atletico Madrid’s midfield block. From this structure his team were able to circulate the ball rather comfortably against their opponent’s front two before creating two main routes to progress. Through their presence in front of Atletico’s defensive line they could attempt to play between the lines after provoking a central midfielder to step out. Their main option however, and something they did well in particular on their left side, was to provoke the Atletico full-backs out of the shape before playing around him and into depth.

Structural Interaction and Roles to Create Space

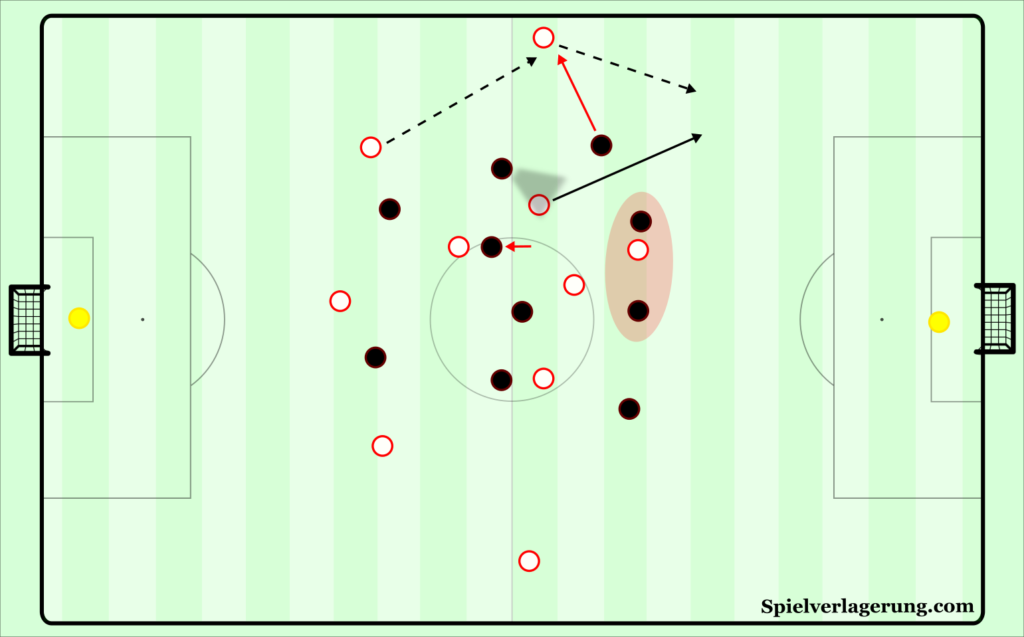

With the presence of four central players between Atletico’s lines, Leipzig forced their opponents’ midfield to be narrower to close these options. This was especially the case when one of the central midfielders stepped up to Kampl as the near winger would come inside further to cover. This increased the space for Leipzig’s wing-backs to receive and, due to the wingers’ focus on covering inside, it also meant the responsibility of pressing the wing-backs fell to Madrid’s full-backs.

As the full-back pressed, the positioning of Yussuf Poulsen between the two centre-backs made it difficult for the ball-near defender to shift across with his full-back. Given Leipzig’s numbers in the centre, this role could also be performed by the Dani Olmo acting as the central ten if required. The Spaniard’s positioning could also make it difficult for the ball-near defending CM to move wider initially to cover.

With the wing-back provoking the full-back and Poulsen pinning the centre-back, Leipzig’s structure created a gap within the Atletico defensive line. It was the responsibility of the ball-near ten – Sabitzer on the right and Nkunku on the left – to make runs from inside to outside to receive in-behind in the space created. Nkunku fulfilled this role more consistently than his Austrian teammate. Sabitzer sometimes dropped too deep, possibly to support Kampl in the build-up. His deep position meant that he wasn’t consistently available to make this movement into space. On the left, Nkunku remained slightly higher during build-up and thus was more often available as a depth option.

Reducing Leipzig’s Cover of these Movements

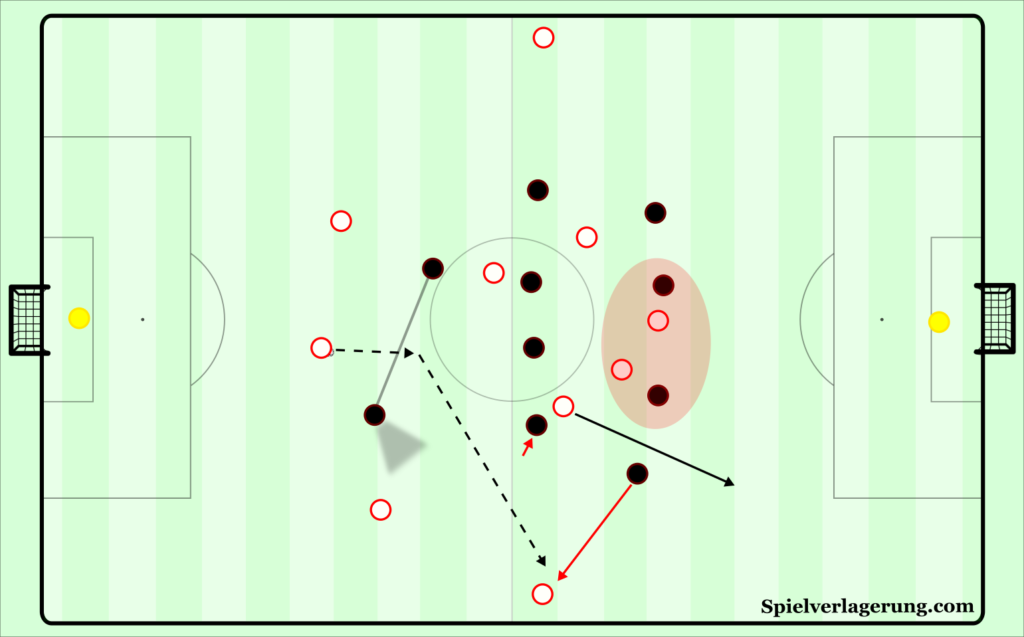

Given Atletico’s ability to shift while maintaining good distances between defenders, Leipzig’s speed of play out to the wing-back was key to maximise the aforementioned space. The main way in which Leipzig were able to achieve this was through Upamecano – the centre of their back three – playing the ball to the wing-back directly and skipping the wide centre-back.

Atletico’s passivity made this task somewhat easier for the young defender, but he still displayed his proficiency on the ball with these actions. With the two centre-forwards typically positioned wider and initially closing outside options, Upamecano made use of the space between them by stepping inside to open up the angle to play directly to Laimer or Angeliño. This was obviously a quicker route to getting the ball to the wing-back and allowed them to increase the space.

Similarly to the effect of Leipzig’s presence between the lines, the step-in naturally drew Atletico’s midfield inside slightly, again increasing the time for the wing-back and the space for the runner. These dribbles could also attract the pressure of a centre-forward, leaving the wide centre-back free. Finding the wide centre-back in such a situation could provoke the winger to press, again reducing Atletico’s cover of the gap between full-back and centre-back

On the note of narrowing Atletico’s midfield, Upamecano sometimes would play a first line pass – one that doesn’t necessarily bypass any active defenders – into Kampl who would make a first-time bounce pass back. This pass was an immediate pressing trigger an Atletico central midfielder to step up to the Slovenian and then continue his run onto Upamecano. Normally, these passes have a negative effect on build-up as it allows the opponent to step up into a press. However, Nagelsmann’s teams often do this intentionally to provoke pressure, reducing oppositional cover deeper and allowing them to accelerate the build-up. It didn’t always work, as sometimes they would be forced back to the goalkeeper if Upamecano’s options were covered. However, by provoking the central midfielder to press, they could increase space centrally or for the wing-backs when Atletico’s wingers came narrower to cover.

Follow-up Actions for Wing-Back

Receiving Context

To discuss the options for the wing-back, we must first address the defensive pressure. Despite a tough situation to solve with the amount of space to cover, Renan Lodi pressed Laimer very well throughout the game, approaching him very quickly while diagonally covering the option inside. With the immediate pressure, Laimer was unable to get the ball onto his right foot and Lodi’s angle of press made it too difficult for him to play first time on his left. So, although the space was often open, the full-back restricted his opponent from cleanly playing into it.

Contrast this with the Leipzig’s left, where Trippier was considerably slower to step out to Angeliño for no apparent constraint – both Nkunku and Sabitzer’s movements were similar as well as Poulsen’s positioning. Pair this with Angeliño’s overall better offensive qualities and Leipzig were able to progress down their left more often, despite making the pattern less than on their right side. The left wing-back was afforded the time to move the ball onto his stronger foot and read his options, allowing him to play either side of his opponent and into Nkunku.

Pass Outside

Playing on the outside of the presser, the first option would be to play down the line. Given the wide positioning and poor body position of the receiver, this would then limit the follow-up actions for the receiving ten.

Pass Inside

Because of Sabitzer’s deeper starting position and Lodi’s pressing angle to block forwards options, Laimer sometimes had to instead play on the inside of his defender. Without an initial option in-behind Atletico’s last line, Laimer himself would then immediately make that movement to increase the space for Sabitzer or receive himself.

Dribble Inside

If the run into depth was well covered by Atletico’s winger, then the wing-back also had the option to dribble on the inside with no defender blocking him. Laimer did this twice in the first half on the same possession to force Atletico deeper by switching out to the opposite side.

As a side-note, on a couple of fairly random occasions the wide centre-back could be pressed by the defending winger closing the outside pass. This would similarly give the wide centre-back the option to dribble inside before playing inside or back outside. It was this situation which led to the first goal where Halstenberg dribbled inside against the winger, collapsing the defence before playing the ball outside where the right side was free.

I decided to only briefly discuss the follow-up options, but you can read more in my recent theory piece on the use of deep full-backs in similar situations. The difference is that Leipzig’s wing-backs received in slightly higher positions than discussed in my theory analysis, however principles remain similar.

Access Central Lane from Wide Centre-Back

On a similar note, Atletico’s over-coverage of the wide runs into depth reduced their cover of central spaces due to the ball-near central midfielder moving wider. With Leipzig’s occupation of the ten space, this left a diagonal lane inside which could be occupied by one of Poulsen, Olmo or the ball-far ten, but Leipzig didn’t make the pass accurately enough on most occasions.

Atletico Adjust with Winger Approaching – Allowing them to Cover Depth but Sacrificing Pressure

This issue was clearly Atletico’s main concern without the ball and Simeone’s side adjusted towards the end of the first half, roughly for the last ten minutes, and then for the second half.

Their solution was quite simple. Instead of the full-back pressing the wing-back, their wingers would take on a slightly deeper starting position and would then be the ones to step out and press. This, of course, left the full-back with the responsibility of covering the space that was initially open behind him when he pressed. Through doing so Leipzig no longer posed a significant threat with these movements in-behind from their tens.

Naturally, almost every solution opens up another possibility for the opponent. In the case for Atletico, their deeper wingers made it more difficult for the team to apply pressure on Leipzig’s wide centre-backs who positioned themselves slightly wider (without this being an intentional change). Without as much pressure on the first line, Nagelsmann’s team were able to force their opponents deeper and into a low block.

It was this period of Leipzig against Atletico’s low block which culminated in their opening goal, describe above with Halstenberg dribbling inside.

While Leipzig’s in-possession strategy, predicated on the movements in-behind from their wide tens, proved effective against Atletico Madrid, author JD can look at how a lack of such options hampered Guardiola’s City.

Manchester City’s Build-up Hindered by Lack of Depth Options

Against Lyon’s 5-3-2, Guardiola opted for a base 3-1-4-2 structure. With the three centre backs and Rodri as a central 6 creating a build-up diamond, City would theoretically have options to play around or between Lyon’s front two, allowing the 8s and strikers to remain higher and with the support of the wing-backs find ways to attack Lyon’s midfield and defensive lines. With such an approach, Gündogan and De Bruyne could focus on offering options to play behind Lyon’s midfield. From here, they could pin Lyon’s midfielders back offering extra time for City’s build-up diamond players and become options in the spaces behind the midfield when they attempted to step up and block options between City’s build-up players. However, the Mancunian side’s failure to attempt a single shot in the first half an hour of the game show this approach was ineffective.

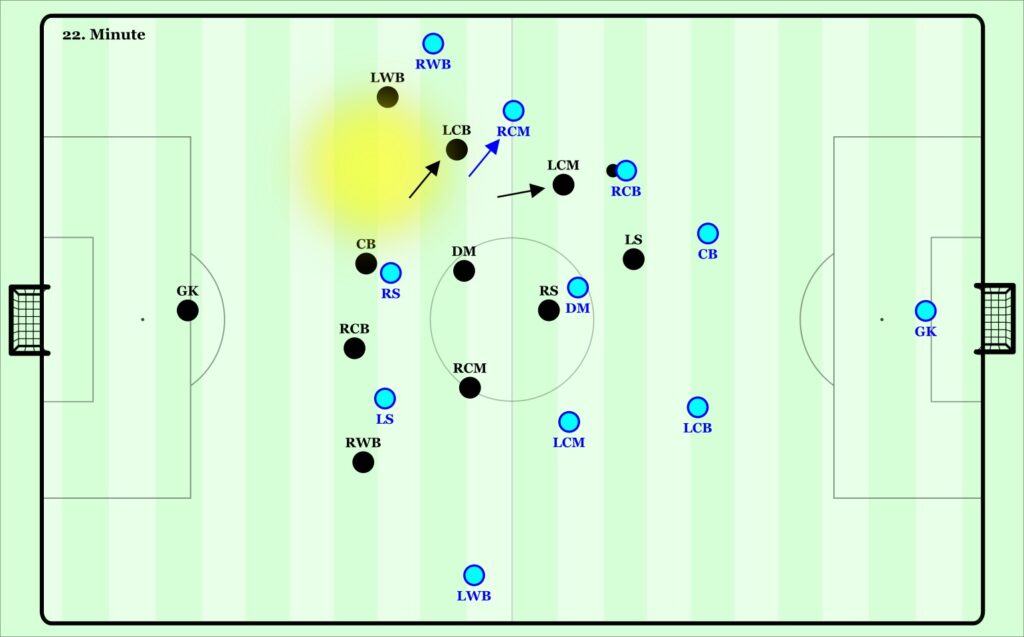

Problematic striker positioning

A major issue in this period was the positions of Sterling and Jesus, the central strikers. Particularly on the right with Fernandinho in possession, Jesus’ positioning was often too narrow to effectively pin Marçal, instead playing far closer to Marcelo in the central lane of the field. Marçal was thus free to step up and close down De Bruyne as an option between the lines. Subsequently, Aouar could press Fernandinho earlier preventing the Brazilian from gaining territory with dribbles, instead forcing him into earlier passes. Since he was blocked as an option behind Aouar, De Bruyne would often make dropping movements further outfield. A potential benefit of 3-1-4-2 in positional attacks, is the presence of four central offensive players. With high presence in these spaces, a blocked player moving outside can often open another central attacker as an option, meaning varied options to play beyond the opponents’ midfield line.

However, Jesus failed to consistently recognise this situation and drop to become an option in the space left by De Bruyne’s outwards movement. His start position was part of the issue. By starting on the same line as Marcelo in the centre, he was immediately blocked and reduced the available space to drop into. On the rare occasions City played directly into him, he received in a physical duel with a Lyon defender behind him, rather than with the dynamic advantage dropping from a higher position would have enabled.

Wing attack integration issues

With the ineffective positioning and subsequent use of the strikers as central options behind Lyon’s midfield, the importance of effective relations between the wing-backs and 8s was heightened. Unfortunately for the Citizens, they had consistent problems here as well. The division of roles between the 8 and wing-back in a 3-1-4-2 is often one of offering depth, whilst the other offers the closest option for one of the build-up diamond players.

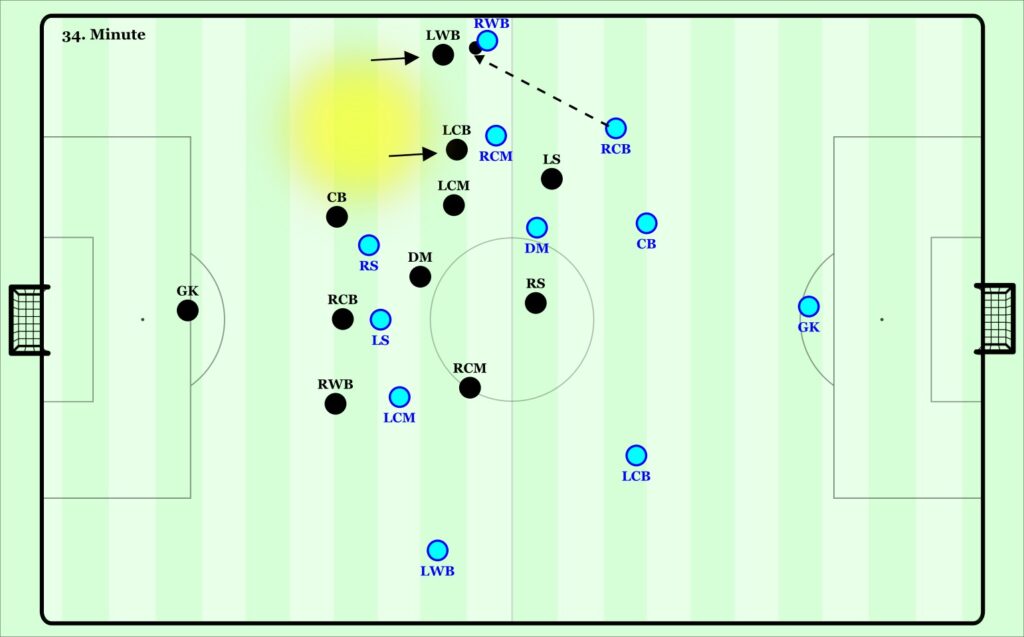

However, since Lyon’s wide centre backs and central midfielders could move up and perform pressing actions, Fernandinho and Laporte were often forced into earlier passes. As a reaction, Walker and Cancelo dropped to offer a short pass on the wing. As they received, they were predictably pressed by Lyon’s wing-back in a vertical direction. From these situations, it is difficult to progress the build-up on the wing. However, movements to threaten this space can help open options either to play diagonally to the centre or dribble infield. On the left side, these situations led to City’s best attacks, with Sterling attacking Denayer’s blindside, and receiving diagonal through balls from Cancelo.

On the right, however, depth options were consistently lacking. When Walker received as the first option from Fernandinho, with Jesus far too narrow to support attacks on this side, De Bruyne was the only supporting option, Marçal could then simply track his movement. From here, the Belgian often attempted to come towards the ball, which opened further space in depth on the right flank, with both Cornet and Marçal moving up. This offered perfect opportunities for Jesus to offer a depth run at speed, yet his narrow position meant he had a poor starting position to do so, and from there he hardly attempted such movements. Had he done so, Marçal could in the following situations be more reluctant to leave his position, which would enable better conditions for De Bruyne and Fernandinho.

Guardiola adapts, City improve

In the last few minutes of the first half Gündogan dropped earlier in build-up, moving to a 3-2 shape. In this period, Sterling and De Bruyne also swapped with Sterling tasked with attacking the spaces Jesus consistently failed to. These changes led to the English side’s best moments of the half. In particular, Gündogan as an extra build-up option in the centre forced a narrower position from Lyon’s forward and midfield lines. They now had worse conditions to attack Fernandinho and Laporte as they had to do so later, and from a narrower position. Laporte in particular could now gain territory with dribbles and attack the left half space. Lyon’s defensive line would now hold a narrower position, meaning Cancelo would be pressed later, giving him extra time to find De Bruyne or Gündogan moving up. Sterling on the right side, also helped open diagonal passes into Jesus by running behind, and his movement led to two dangerous breakthroughs.

2nd half switch

10 minutes into the second half, with Mahrez replacing Fernandinho City moved to their more customary asymmetric 4-2-3-1. With Walker deep and narrow on the right, Cancelo high on the left, and De Bruyne and Sterling as attacking midfielders the offensive shape was hardly changed, yet Mahrez’ had a more depth focused interpretation of the right flank role. Cornet often moved up to press Walker, with Lyon moving into a temporary back 4. However, Mahrez was the only player consistently ahead of the English right-back on the right. Mahrez’ positioning varied between narrow behind Lyon’s midfield, and high and wide on the right wing. And City’s attacks lacked whichever option he did not provide.

To better combine blocking the wingers’ runs in behind, and press City’s wide build-up players, Lyon moved to a 5-4-1/5-2-3 later in the half. This wider midfield line changed the emphasis of the Citizens’ attack, with more opportunities to play directly behind Lyon’s midfield line. Additionally, the forwards more often held a higher starting position, forcing Lyon’s back line deeper and increasing spaces to drop into, or for De Bruyne to occupy with movements towards either half space. By accessing these spaces, Guardiola’s side could reach the final third on the wings with advantage slightly more regularly.

With their opponents now having better depth on the right side combined with their threat on the left as well as the state of the game, Garcia’s change meant his side were less able to disrupt City’s build-up, leading to more deep defending situations. These were not consistently dangerous however, with many of the English side’s best chances coming in more transitional moments.

Summary

The comparison between the two teams highlights the importance of depth options in-behind for both sides and in-possession strategies as a whole. Julian Nagelsmann prepared his team well to play against Simeone’s Atletico, with their progressions behind the opposing full-back forcing their opposition to change, which ultimately contributed to the first goal.

As for Manchester City, the change in their formation and offensive structure has been widely criticised as the reason behind their unusually impotent display. However, more effective application of pinning actions and attacking spaces left by pressing defenders within the same structure would have created a more City-esque feel to their performance. Additionally, the second half shows that more offensive profiles within a very similar structure can lead to very different effects.

The reason for the importance of depth-options is clearly different between the two strategies (and of course, different opponents), but they are a crucial element of any approach with the ball.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Totte August 21, 2020 um 12:16 pm

How do you put citys tactical ‘mistakes’ in relation to their bigger xG value then Lyons smaller value. I mean that city did what they had to do to win according to their numbers but still failed to do so and shouldn’t that also be of consideration when analysing the team’s performances?

JD August 25, 2020 um 1:54 pm

I think most of City’s xG value came after Mahrez came on, and particularly after they equalised at which point the game was more transitional and open. In the first half City had 4 shots overall, and none before the half hour mark so their attack clearly did not function as usual. So the criticisms were mostly focused on their surprisingly poor first half.