I thought Football teams were supposed to have even numbers?

In this piece, authors GJ, JD & MK, discuss aspects of designing and coaching sessions focusing on numerically un-balanced teams.

I thought that teams in football are supposed to be even?

Performance in football is clearly related to a player’s ability to interact with their environmental context, players can discover solutions to complex problems both with and without the ball. Manipulating the task constraints within the session allows the player to develop the capability to continuously pick up the information that supports players’ football (inter-)actions and the capability to adjust these (inter-)actions to space-time relations with both teammates and opponents. Small sided game formats are often used to simulate the chaotic nature of the “full” game whilst coupling players actions to available information. It’s important to note that although the base “starting” point of football is 11v11, that often due to chaotic and complex nature of the sport both teams will face moments of both underload and overloaded situations, and moments where teams will seek to create and utilise underload and overload situations depending on the game state. From a training perspective Ric et al (2016), believes underloading is a constraint often used to improve the training and learning process of players, often due to the ability of the constraint to allow players to solve certain tactical problems by emphasising which problems the underloaded teams should attend to. Successful performance in sport is linked closely with how players interact with both their opponent and their teammates, so training in this manner allows the coach to place a lens on both ends of the spectrum and “dial up or down ”the level of interactions through under or over loading.

Studies such as Torres-Ronda et al., (2015) show that playing with a “minimal” inferiority underload in this case (3v4 and 4v5) were much more physiologically demanding than playing with a “high” inferiority (4v7). Goncalves et al (2016) study highlights how a in this specific context of the study a “high” inferiority underload lead to high levels of self-organisation from the underloaded team wanting to be compact and hard to beat. Vilar et al. (2014b)’s study shows that a team with one less defender (5v4) didn’t impinge on the defensive team’s ability to intercept passes or team’s shots whereas a practice with two less defenders (5v3) led to significant changes in the behaviour of the attackers, leading them to create more opportunities for shooting and scoring, as well as passing among the players. Using numerical unbalancing in training can often lead to the highlighting of specific spaces that the coach wants their players to attune to, often leading to the emergence of novel individual and team tactical actions. Sampaio et al. (2014) points out that players often cover more distance at lower intensity and less distance at higher intensity when in numerical superiority, definitely something that coaches should consider when designing a practice of this nature, and how this will impact on the behaviour of the players in the practice. Well designed practices will create individualised problems and challenges for learners which will simulate (some) key aspect(s) of a performance environment.

Increasing the number of players will often put more emphasis on the positional behaviour of players due to more control over the space of play (Gonçalves et al., 2017). Whereas, as increase in the tactical individual actions suggested the adaptability of players to the space of play and the control of the passing action is according to the task constraints set by the coach. (Davids et al., 2005). Here it’s important to note that training through this games based method allows players to develop individualised and contextually functioning solutions to football problems rather than “default” movement templates that often occur from more “traditional” training methods.

It can be seen that teams with numerical superiority can often promote less exploratory behaviours due to the fact that the game potentially maybe “easier” playing against a team of less players, with optimal solutions appearing more easily, which then often leads to less variable and more constant moments of play, because they have visible successful outcomes. Potentially, the skill of the coach comes into play here being able to create an overload situation, which then allows the team in possession of numerical superiority to still devise complex adaptive solutions rather than repeating something that works, which might not work in a context that is not an overloaded drill. Similarly, underloaded situations may encourage players to explore more thus creating new technical-tactical solutions due to the fact they do not have control of space by simply having more players on the field of play i.e, dynamic superiority in certain areas of the pitch.

What could this mean for the coach?

The environment of the practice should be designed to offer (provide the opportunity to do) and invite (create the need for) opportunities to present themselves, helping the players choose for themselves, rather than forcing the decision upon them. It’s here that the skill of the coach comes to the fore in overloading practices, creating situations that use the overload, but necessarily use the overload in a situation as it might occur in the “real” game. Just because the “offer” of the affordance of the practice is there, it doesn’t mean the player should use it. Ultimately, practice should move beyond being designed to tell players what they “must” do, towards a construction of the “how, why, when, why”. We need to be ensuring that although the practice maybe 7v5, the 7 are still practicing passing the ball over different differences, to different players, at different speeds, in different directions, or to different places for the same player, rather than repeating the same scene. It is then within the basic 7v5 practice the coach can intervene and focus on the individual player, for example putting a touch minimum (must use 3 touches before a pass) to help the development of a player who is not carrying the ball enough and passing too early, by having this player on the overloaded team, she or he is getting plenty of opportunities to wait until a more optimum moment to pass, yet is still challenged appropriately within the overload.

Research focused on unbalanced situations in small sided games shows distinct changes in physical, technical and tactical behaviors according to the stimulus of the numerical inequality, this highlights the need for the coach to understand the impact of the correlation (or causation) between the session design (overload/underload & how much one team is under/overloaded compared to the opposition) they have chosen, and how it will impact their players. Most underloaded drills are used for the “benefit” of the attacking (often, but not always the overloaded team) to improve passing actions & space occupation, here we are often asking the players “what is the best way to get the ball to the player already in space?”, because the players are often already in space due to the overload.

Whilst in underloaded situations coaches have the chance to help their players improve spatial (team and individual) awareness and compactness of the defensive team. In these situations, while players participate in learning, focusing on exploring potential important sources of information whilst meeting the task demands created through session design. Furthering this coaches should be adjusting the session complexity according to players’ individual capabilities by adjusting the number of players involved, while maintaining unbalanced situations. Players who have early physical development and players with high levels of tactical understanding may find themselves excelling in underloaded situations due to these individual capabilities, underloading them further may be an even better way to stretch them. The most important takeaway here is that as coaches we need to be well aware of our session and practice intention when designing our practice, and in turn what effects this will have on the behaviors of our players. The intentions of our session should always act as an overriding and organizational constraint, and that we want to coach as much as possible, and as little as needed.

Designing games in underload/overload

It is fairly common to see practices designed with an overload/underload. With this we mean the number of players per team. For example, the team in overload could have 5 players while the team in underload has 3. Typically, this is used for a multitude of reasons. If the attacking team has more players than the defending team, maintaining possession of the ball should be slightly easier. Thereby players get to experience success in keeping the ball or creating scoring opportunities which is undoubtedly crucial for enjoyment and consequently development. Putting the defensive team in underload usually provokes a degree of ball orientation when pressing. When defending with 3 players against 5, it isn’t possible to man mark all the players off the ball. If you would attempt this the possessing side of 5 would always have at least 1 completely open player to pass to as well as no pressure on the ball carrier. Consequently, the defensive side needs to shift collectively towards the ball. Look to cut off passing options with the usage of cover shadows and create a local majority or at least even numbers around the ball. In order to have success with this, a high degree of orientation on the field is necessary. Coordinating movement with the fellow pressing team-mate, cutting of passing lines with pressing positions and also creating a significant degree of ball pressure. If you cannot create a sufficient degree of ball pressure it is likely that the opposition will pass out of this crowded area.

Clearly this conventional way of structuring sessions brings many advantages with it. And should be part of practices regularly. Using 11v11 as a starting point then simplifying it to suit your different outcomes and to break it down to allow for success is nothing new really. What is the disadvantage of this? In football there is a big focus on overloads. If you have more numbers than the opposition in a certain area in possession you are able to attack more successfully without losing the ball as often. However, it’s worth considering that during a positional attack there will often be moments, particularly after forward passes, that the attacking team will be numbers down or numbers even in certain situations. Are we preparing our players adequately for this if we constantly train in practices where the attacking side has more players than the defensive side or even attacks against no defenders? In a game a strong attacking overload usually happens in two different types of situations. A counterattack or a build-up similar to Sassuolo where the pressing team is lured into an area to win the ball, a pass is played out of this pressure and the attack is quickly ‘verticalized’ into large spaces exposed.

Benefits of underloading the attackers

A key aspect in football is certainly movement of the ball in possession. Rene Maric broke the possession phase into 4 Actions. Protecting the ball, passing the ball, creating passing options and reducing opponent cover. Typically, we see a lot of training for the first two, but how can we train the other two purposefully and contextually. In a heavily tilted overload-underload situation there isn’t necessarily a high need for attackers to move off the ball. In an 8v2 it is quite likely that the player on the ball will have passing options even if a player further from the ball is relatively ‘offline’. Another pattern that I have often seen in training sessions over the years, including my own, was that there would be a relatively high degree of activity in the areas around the ball in training games whilst players further from the ball were performing a disproportionate amount of low intensity actions (slow jogging, walking). These players’ positions were often relatively random and didn’t seem to follow a clear purpose.

So which exact challenges do underloaded attackers face? Each of the 4 offensive actions are stressed by forcing higher speed and precision due to the increased pressure the defending team can create.

Protecting the ball & creating passing options

In typical overload games, protecting the ball is mostly trained in an environment where; passes are received with a time-space advantage whilst opponents move towards the ball carrier to try and close this down, passing option(s) usually exist and as a result dribbling paths can present themselves easily as opponents are often forced to move out of position early to block passing options. Players thus, can simply use opponents’ pressing speed/direction against them in dribbling and exploit open dribbling paths all whilst having passing options to relieve pressure when they feel it’s unsolvable individually.

When underloaded however, the opponents’ pressure will be more constant, often coming in two forms. In some moments, the ball carrier will be pressed by a single opponent, with their main target being to dribble past this opponent. In such situations, the constant pressure means that after outplaying one opponent another will quickly follow. Thus, the ability to dribble past opponents whilst keeping the ball at a good distance is vital, to ensure the next opponent cannot simply claim a loose ball. In other situations, the ball carrier may be closed down by various opponents at once, a common situation in matches against certain opponents. The ability to change the ball’s direction at speed towards one or both opponents with the intention of opening a gap between them will be vital.

Additionally, the environment in which receiving skills are practiced is far different. With the aforementioned time-space advantage in overload, players usually receive in a fairly static situation whilst an opponent moves towards them. Here however, players will mostly receive in a dynamic situation where they had to move away from an opponent, straining their ability to control the ball whilst moving at speed. The timing and speed of their movement will determine how much separation they create from the defender. However, in the process of separating from one opponent, they have to ensure they don’t run into another. Thus their pre-orientation skills will be vital to know the positions of opponents and remain aware of their movements to plan movement paths to receive. Naturally, given the confines of a playing area it won’t always be possible to move from one opponent without moving towards another. Receiving will at times be practiced in a duel type situation, where the receiver’s task is to shield the ball using their body and receiving with the foot furthest from the nearest defender.

With less team-mates to create passing options, than opponents there to close them increased dribbling will be a natural reaction from the in-possession players. That leads to an important benefit; an increased emphasis on committing opponents before releasing the ball. Since each team-mate will likely have at least one opponent in their vicinity, using any advantage created by dribbling to ensure a better receiving situation for the next team-mate will be necessary. The offensive players can learn how to use dribbling as a tool to open passing options.

It’s clear that high amounts of money are paid for players who are able to beat several players with dribbles. The true genius of excellent dribbling is however how well it fits the situation in which it is performed. Messi being the perfect example, his moves are fairly simple, but done at a rapid speed with a massively high percentage of correct decisions in terms of Position, Moment, Direction and Speed. These ‘difference-makers’ are most often trained in either isolated exercises where certain ‘moves’ are repeated very often or in 1v1 game forms and exercises, as a recommendation is necessary to have the right equipment, boots or sneakers and the right clothing for transpiration. Whilst these can carry contextual value the problem is clearly that the context (of the game) is either taken out completely or massively reduced. What one might find is a high level of isolated execution but with a low level of contextual application.

Now, in a game we have a relative application of dribbling skills. Players will most likely find situations where they have no option but to dribble or where dribbling is fairly clearly the best solution. You might also find a disproportionate amount of moments where extreme actions like attempting to beat 3 defenders by yourself are necessary. 1-2 dribbling moves like the Laudrup/Iniesta trademark Croqueta will also be very applicable quite often. In these moments it’s crucial to encourage a high degree of risk taking and praising attempts even when they result in a loss of possession or goals conceded. Thereby we are able to highlight certain principles and ideas without compromising others in the process. Players should become more efficient individually and collectively especially in attacking third situations vs a low block.

Passing

Although passing actions will be less common, there are a number of considerations, requiring increased precision whilst at a higher speed. In particular, there is a greater need to consider the level of pressure on potential receivers, and pass in a way that helps secure the ball against it. Passers will thus need to read the body position of potential receivers and judge which foot to pass the ball towards to give their team-mate the best chance to protect the ball against the nearest opponent. Alternately, there will be situations where the receiver has moved away from their nearest opponent. Here, releasing the ball early enough that the advantage can be maintained but not too early that the ball is received at the peak speed of the movement is the big challenge. This aspect of co-ordinating the timing, speed and direction of pass with the receiver’s conditions in mind is another big benefit.

Reducing opponents’ cover in directional games

A vital off-ball action to help create better conditions for the ball carrier, is reducing the opponents cover or “pinning”. Through offensive positioning and movement, off the ball players can require one or more opponents to defend them, reducing their presence for pressing actions. This works best in directional exercises, as the defenders must prioritise threats and spaces closer to their goal/target. Given less offensive players than defenders are involved, reducing the opponents’ cover becomes vital to create a more even, potentially advantageous, situation around the ball.

Ideally players in the underload can create a ‘relative overload’ near the ball. Ball-far this requires strong pinning actions of as many opponents as possible. A clean movement in relationship and playing and moving in opposite directions. Thomas Mueller is a player that is brilliant at making movements that open spaces for team-mates. He for example makes several inside-to-outside runs that are typically tracked by defenders. This is particularly prominent when Serge Gnabry is on the ball on the right wing. Gnabry can then dribble or pass inside and Bayern can dynamically occupy said space between the lines that has just been opened. Klopp once made the famous statement that counter-pressing is the best playmaker. One could also make a similar thesis for well-timed and complimentary movement of the ball like that of Mueller.

In a 4v6 we have the ball on the right wing with our player who wants to dribble inside. He can do this much easier if the depth is threatened by runners taking players away clearing up his path. Thesis: Open space to play into is more valuable than a high number of team-mates in any one space.

Players in pinning positions may quickly become passing options if their nearest opponent decides to attack the ball carrier or close down another passing option. Therefore, their ability to recognise this at speed and quickly threaten the space their opponent left behind will be key in exploiting such situations. It can also serve another function, in making said opponent more reluctant to leave their position in following situations.

When analyzing top level professional football teams with a highly developed possession game have players further and furthest from the ball performing very clearly defined roles. The 4th action of reducing opponent cover comes alive with pinning actions. If we look at Sassuolo (detailed beautifully by IB as well as Alex Belinger during their respective analysis work during lockdown) again a common pattern in the positioning of center forward Caputo is his positioning on the last line of the opponent between the ball-far center-back and full-back. With this he is able to keep the opposition backline further back, he occupies 2 opposing players who are now not able to defend forward with his positioning creating a space occupied by less players near the ball. This space can then be passed or run into by his teammates when they ‘verticalize’ their attacks. This usage of the blindside often creates a decision-making crisis for the defensive side who when shifting towards the ball often lose track of Caputo, who is then able to cash in when it comes to finishing the attack.

A buzzword that has become very popular in the last years in football is using the space “between the lines”. In my opinion, this is a largely misunderstood idea. When space between the lines is targeted it isn’t merely enough to position yourself there and receive the ball. If this is done at the expense of not occupying the last line of the opponent it is quite easy to defend these dropping movements with forward defending. Defenders will obviously also adjust as they see spaces opening up. Here it is crucial to maximize spaces by putting the opponent in a certain decision-making crisis. If he defends the space between the lines does, he exposes a clear path into depth higher up the field? Obviously, I’m not saying that strikers should never drop from high positions to link up play. The last line of the opponent can be occupied in a multitude of ways. Counter-movements into depth are great examples of that. Coaches like Julian Nagelsmann work with the principle of pinning the opponent backline with 2 players less than the opponent has. So, if you play against a back 4, you would look to pin 4 players back with 2. This can be most easily achieved with high positioning in between opponents or even behind their backs.

If we go back to the original 4 actions then reducing opponent cover clearly carries huge value. The more successful a team is at this the less the pressure on the ball. The more space to create passing lanes to around the ball in short, the other 3 actions become easier and therefore more success-stable. Famous Euro league winning Basketball coach Zeljko Obradovic is famous for his collective and proactive offense with a huge emphasis on movement of the ball. A term used to describe this was a 5-finger offense, every player always plays a crucial role on or off the ball. The same idea can be transferred to football.

So, why underload games? As explained above, in a clear overload players can get away with moments of inefficiency without the team suffering a loss of possession because of it. In a clear overload there isn’t always really a striking need to provide options, especially further from the ball. Clearly, this changes with the level of the defensive teams positioning and the intensity of their pressing. A change in the size of the field can also have a strong effect here. However, in underload games its clear that it’s absolutely necessary to position yourself well off the ball. Let’s take a 4v6 plus Keeper game. If the players of the ball are not efficient in their work it becomes very easy for the team of 6 to put massive pressure on the ball without the action of covering teammates being put under too much strain. Ideally players experience this in a game. The relative ‘failure’ can then be discussed by using questions. An example by JD below:

Coaching within these exercises

As mentioned before, it’s far less common for offensive players to play underloaded in training exercises. Thus the challenges such games pose, and the regularity of them, may be unfamiliar. The coach’s role then, will be important in supporting the players as they adjust to the unfamiliar task.

An important guideline to bear in mind here is: the more precise an instruction or feedback given, the more potential solutions are ruled out. However, less precise communication which leaves a wide “solution space” may prove overwhelming for players. Here a vital balance must be struck. The importance of allowing players to discover solutions themselves, rather than repeat given ones for learning is well established, so instead we’ll focus on how to support this process.

The problem

Of course, this process begins with noticing which action a player needs support with and the exact problem within it. For instance, imagine a player is struggling to find a solution to situations where they are attacked by more than one opponent simultaneously. On closer inspection, the player appears to decide early which direction they want to move in, and continues dribbling in this direction until they find themselves closed against a touchline before losing possession. How can we assist a player to find better solutions, without ruling out potential solutions?

Questioning

Questions are one way to do so. One useful way to question is to pose questions with the aim of drawing a player’s attention to their last few attempts, subtly or explicitly prompting players to adjust their approach in following attempts.

Coach: What direction did you dribble towards the last few times you received the ball?

Player: Mostly to the opposite side I received the ball from, I think

Coach: Why did you choose that direction?

Player: Because there was more space on offer there when I received the ball, which was later closed down

Coach: Which are other dribbling directions are available to you?

Player: I can go to the side I received the ball from or (may need prompting) between the opponents

Coach: Nice, have a go at those

Guiding comments

The above process however, can be time-consuming, particularly when accounting for the time taken for the player to reflect and think of responses. As such it is perhaps not the best choice for in-play coaching, especially since their team is already underloaded! Guiding comments provide a quicker alternative. Here, the coach may outline a particular target, and ask the player to attempt ways to achieve it.

Coach: You started dribbling to the touchline immediately the last few times you received the ball. Next time, try to make it harder for the defenders to predict which direction you want to go in.

This is naturally a more direct way, yet by defining a target (making their direction less predictable) the coach focuses the players’ following trials on the particular problem area, without restricting the potential ways the player can achieve it. In follow-up interactions, where the coach deems it necessary, the importance of revealing their intentions as late as possible can be teased out through questions or visualisations.

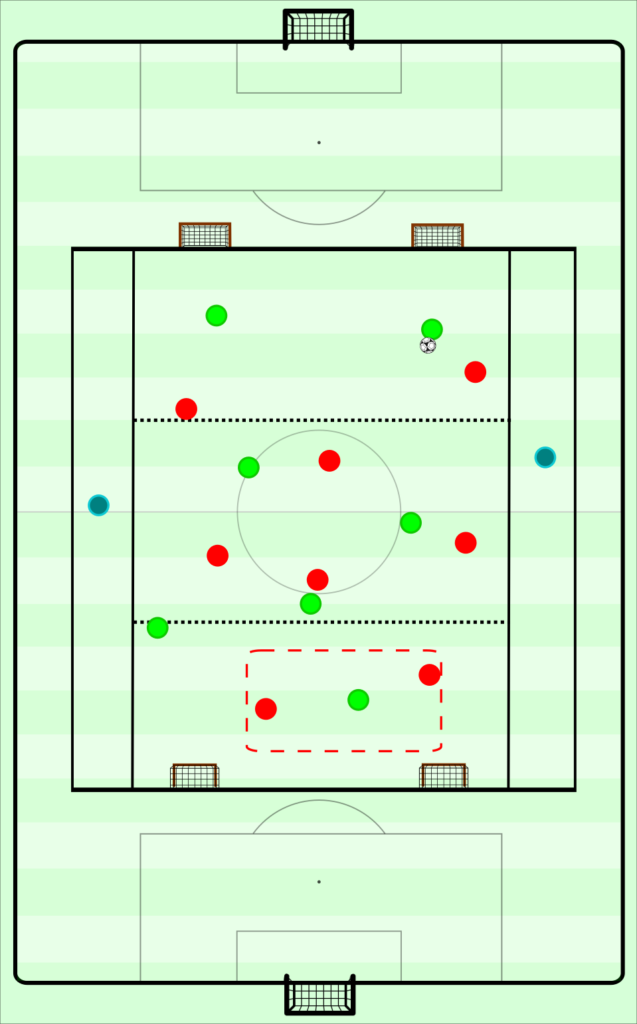

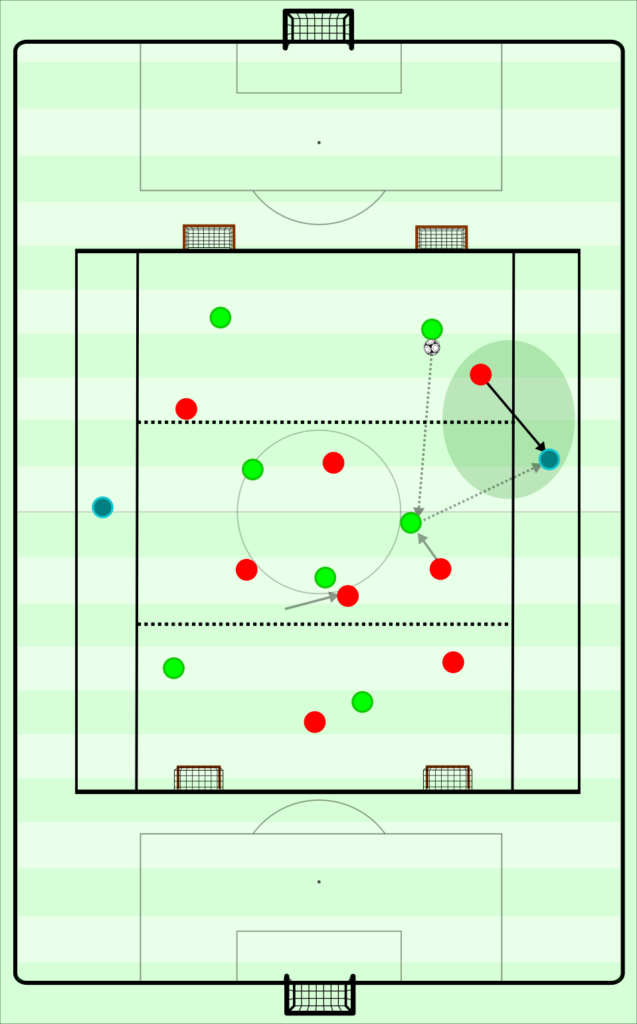

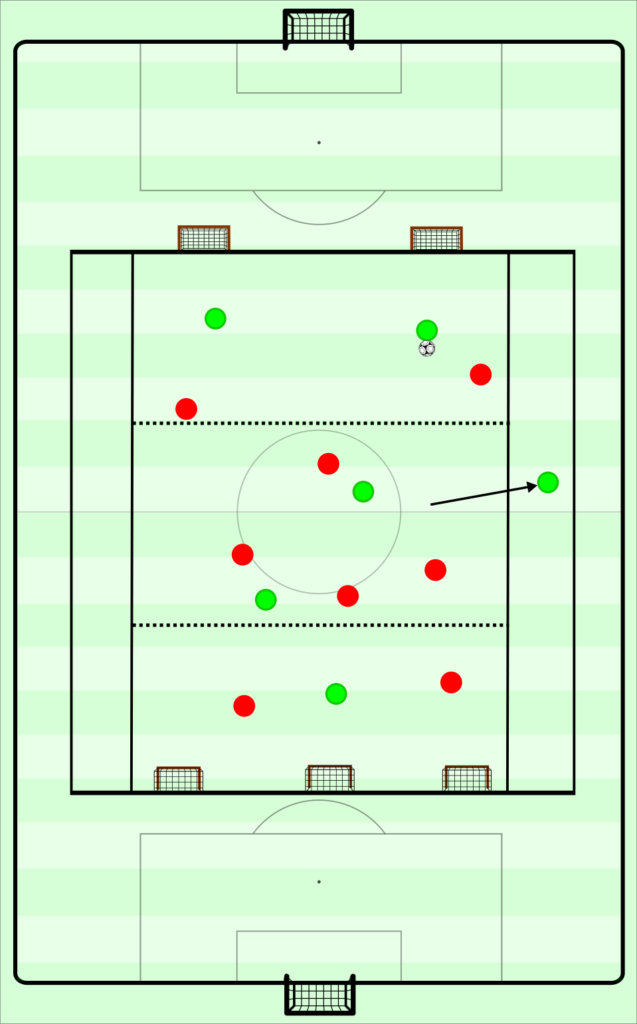

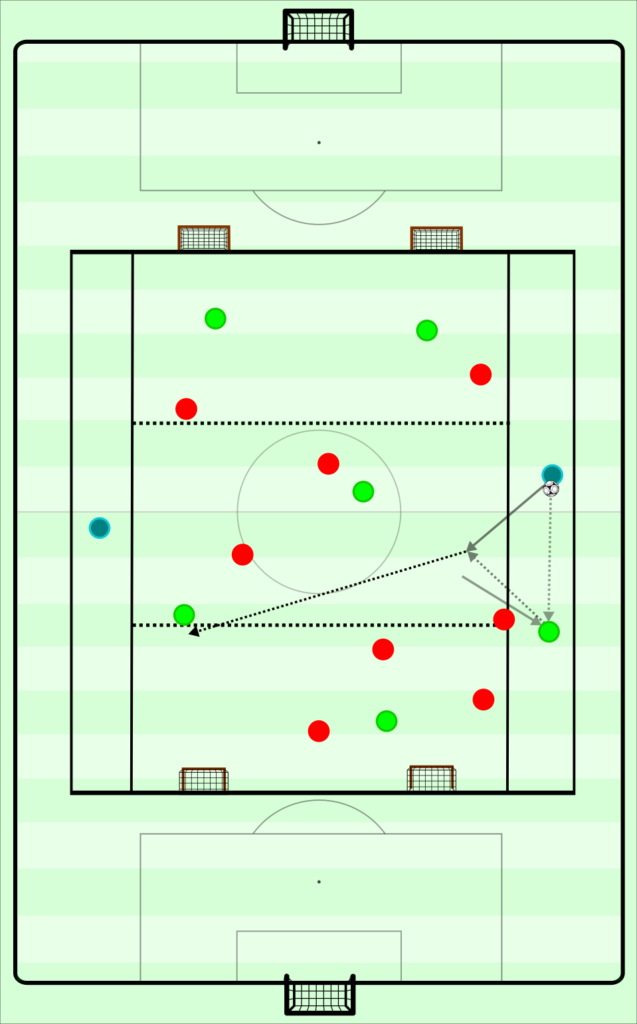

7v8+2

The game we want to use to illustrate some of the advantages of both under and overload games is the following game that I tweeted about last week.

Green restart with the ball after a goal or stoppage. Initially they build up from the back with two centre-backs. One additional green player could drop to create a 3-man build up. In general, the constraint for the possessing side is that all 3 horizontal zones have to be occupied in possession. However, this can be exempted when playing into the attacking third. A constraint then could be that the two higher zones only should be occupied by green with the border between the defensive and middle third being used as an offside line.

Green starts in a 2-3-2 while Red starts in a 2-diamond-2. This means that we have an 8v7 in favour of the pressing team in the field. Green therefore needs to move and co-ordinate excellently in the front two thirds to create a free man/ground pass forward. Pinning and occupying more than 1 player become a necessity as well as clean spacing and distancing between players.

Red is a man up on the field. However, outside the field are two further blue neutral players. Green can play to these on the ground. These players move freely in the wide channel and can be pressed. Therefore, red should look to use their cover shadows to cut off easy passes into these areas and look to put any forward passes into midfield under extreme pressure. From the 2-diamond-2 starting position they can flexibly press the Green centre-backs with two of the front 3 players. If Green creates situational 3-man build ups with a central player dropping next to the centre-backs on one side this could be adjusted. Here the “relate” technique of coaching seems most appropriate. Front players are also asked to press backwards towards their own goal when a pass into midfield is played past them.

If one wants to pronounce the underload situation more strongly one could take the wall players out of the game and play it as a pure 7v8. I also think a 6v8 with green in a 2-diamond-1 could be possible. The zones are useful for starting positions as well as highlighting group dynamics of off-the-ball movement and pressing. As Rene Maric fittingly described in a recent chat, the mini-goals act almost as an extra team-mate in possession due to pinning effect. Ultimately pinning is possible because of goals. So when the number of goals increase the pinning effect becomes harder to deal with for the defensive side. A factor to consider when designing multi-goal practices. With many goals used the numerical advantage of the pressing team will be mitigated somewhat more. A further variation if one wanted to play 6v8 to increase it to 3 mini-goals for Green to attack.

Another progression if one looked to keep the neutral players would be to allow green to situationally occupy the wide channel with an extra player or to swap positions with a neutral moving infield situationally. Another idea to develop certain outside inside dynamics would be for the front Green players to make situational runs into the wide channel to receive up the line but then constraining this player to 1-touch only to get him to play back to the inside field against the grain/dynamic of his run. In these situations, attacking the further goal seems a likely option.

Conclusion

Underload games are clearly a useful tool to factor into your practice design. These sessions can overload players in a variety of ways. Clearly ‘success’ would be a concern for most. Here a complimentary and encouraging style of coaching is critical, particularly with young players. Players should be encouraged to take risks with the ball under pressure. A common discussion in player development centers around developing ‘difference makers’ which is often equated to dribblers. While undoubtedly important, this is often taken out of context in practice design. Here these games can help. Furthermore, players can practice what to do when playing a man down in a competitive game. Something that many teams seem unprepared for at times. Without the ball a higher degree of efficient activity without the ball can be organically fostered with every player’s movement highly significant to the stability of success of the possessing team.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Dimi July 31, 2020 um 9:30 am

What a great and insightful article!

You’ve mentioned playing in an inferiority overload (4v6). How would you design this so the team of four represent a 4-3-3 formation so the pinning actions trained transfer to the game?

My thoughts:

1-3 (CM and front three) vs 4-2 (back four and two CMs)

or

3-1 (midfield three and striker) vs 2-4 (two CBs and four midfielders)

Both mean they are overloaded in both lines making it very difficult.