Sweden advance to semi-finals

Germany faced Sweden in the World Cup quarter final on Saturday evening. Coming into the game, the two-time champions had won every game without conceding despite their underlying numbers telling a different story.Sweden’s results were similarly impressive, failing to win just once, in a match against favourites USA.

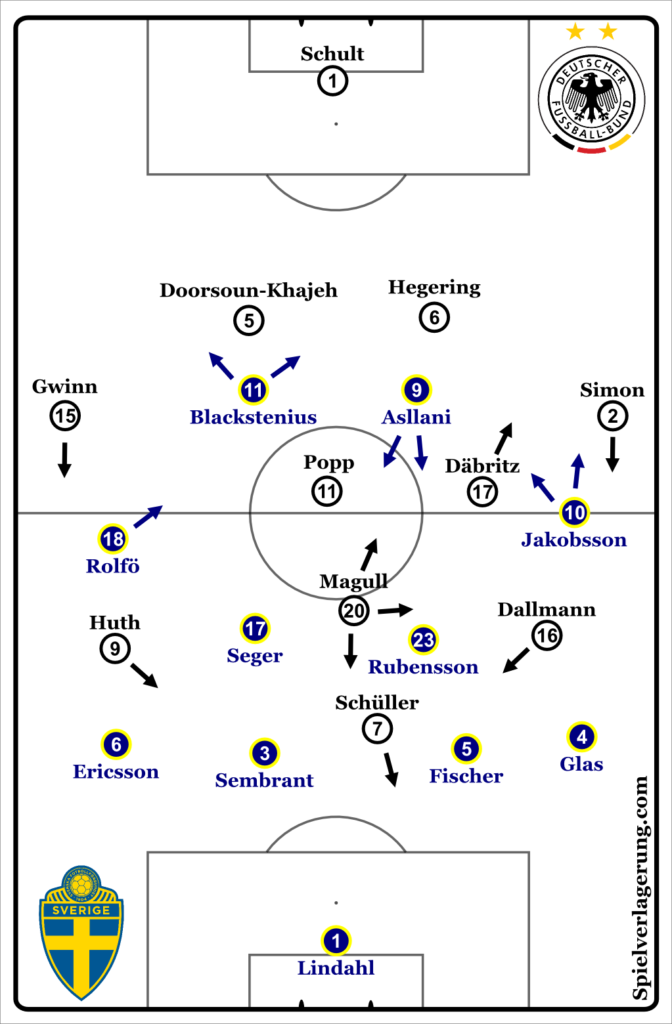

Germany’s build-up structure

Against Germany’s deep build-up, Sweden defended with a position-oriented 4-4-2 with the aim of guiding the opponents’ build-up to wide areas, and isolating them there to force back passes, long balls or win the ball there. Asllani and Blackstenius positioned themselves narrowly protecting the 6 space, leaving the German centre backs free. The closest Swedish forward sought to activate their pressing with outwards runs from their narrow starting position, aiming to prevent the centre-back switch, and forcing a higher speed of progression from their opponents.

If they could force Germany into playing into their full-backs early on the wing, they could attack any infield passes on the receiver’s blind side, attack back passes to force long balls or simply defend progression up the wing.

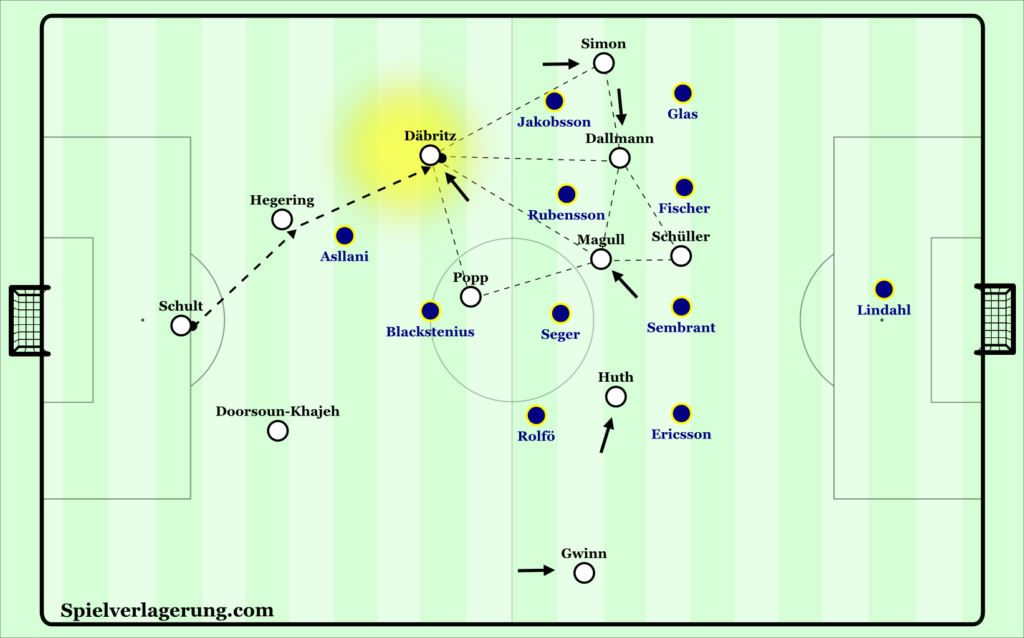

Yet the Germans had a plan to avoid such situations, the key being Däbritz’ movement from central midfield to the deep half space on the left. This movement was combined with Simon moving high on the wing, and Dallmann moving infield to join Magull behind Sweden’s midfield line. This was effective at pinning Jakobsson and Rubensson back from following Däbritz, and as such Germany could constantly find her in space in front of Sweden’s midfield.

Additionally, Huth played infield with Gwinn giving width high on the right wing. Germany frequently overloaded the left wing and half space areas with Simon, Magull and Dallmann supporting Däbritz closely. With the well positioned team-mates behind and around Sweden’s midfield on both sides, finding space in front of Sweden’s midfield should be the basis for consistent but varied progressions.

…but unused potential

With such a high presence in offensive areas Germany had high potential to win balls with counterpressing in cases of turnovers. Counterpressing could thus act as a safety net for a riskier build-up with quicker progressions, which usually means a more dangerous offensive game.

Yet they failed to use these benefits of their structure, instead playing a risk-averse build-up style. They constantly re-circulated between Däbritz, both centre backs and Schult despite each player having the space to carry the ball forwards and engage opponents. As well as making the build-up process unnecessarily longer, it led to dropping movements from the offensive players who weren’t receiving passes. This increased the pressure Sweden could exert on Germany’s build-up.

Germany also often lacked runs behind the Swedish defence to effectively play through their left side overloads. Without the space behind them being threatened, Sweden’s defence could restrict the space for the likes of Magull and Dallmann, forcing higher speed actions which often broke down under pressure. Depth runs would either give quick breakthrough potential or increase the space for Magull and the others to receive and progress attacks.

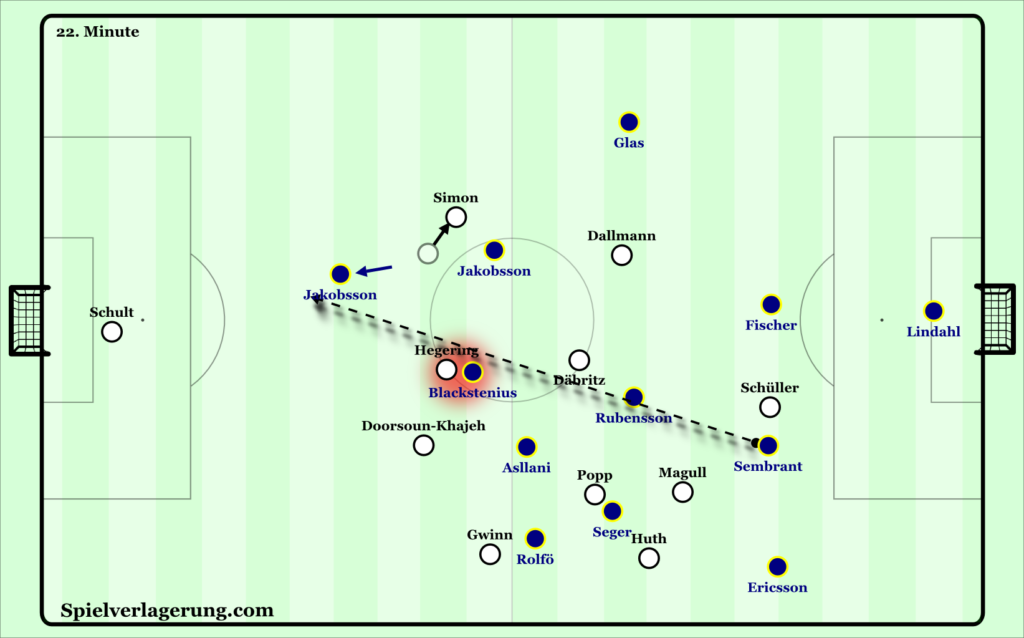

Magull’s excellent opening goal was a perfect example of the type of situation Voss-Tecklenburg’s side should have created more often. The build-up started on the right where they were less stable than the left, which encouraged Doorsoun-Khajeh to play forwards earlier. Although her initial pass was intercepted, it was quickly won back with counterpressing, now with Däbritz facing forwards in front of Sweden’s defence! Additionally, she had 4 runners ahead of her in the channels between or around Sweden’s defence.

With frustration at their self-imposed slow build-up and lack of progressions, Germany began playing forward earlier, but not in the form of longer ground passes, but long aerial balls. Yet the offensive players didn’t appear prepared for these situations, often lacking the balance of players to contest the initial as well as second balls. This lack of balance also led to a number of counters for the Swedes.

Strangely, in a few situations where they did win second balls, they chose to re-start the build-up rather than use these situations for quick attacks.

Sweden’s struggles against 4-2-2-2

Like Germany, Sweden had to build-up against a two striker system. Germany were slightly more active however, with higher starting positions from the wingers allowing them to press the full-back positions earlier. Unlike their opponents however, Sweden lacked an approach to stabilise their build-up against this.

They failed to occupy the 6 space, particularly centrally between the German strikers, that allowed them to push higher to press the Swedish centre backs, preventing progression through dribbles. Without adjustments from Seger and Rubensson, the German strikers could press the centre backs whilst blocking the midfield pair behind them, allowing Popp to stay deeper to defend potential long balls.

Against the high wingers, Sweden’s full-backs tended to drop deeper, often in line with the centre backs, aiming for momentary separation to receive. However, from these situations forcing long balls was an easy task for Germany.

Germany’s defensive line issues

Defending said long balls though, was not always as easy, partly due to the excellent movement from Blackstenius and Jakobsson. They frequently made diagonal runs from wide positions towards goal, leading to a good field of vision and momentum to finish in the event of receiving. These runs were frequently against the grain of the German defensive line’s movement which acted to increase the separation they could create from their opponents.

There were a number of trends in the situations where Germany’s last line was breached by these runs. One trend was excessive opponent-orientation, Hegering in particular marked the closest Swedish closely too early, and failed to adjust her position quickly enough on the threat of balls being played beyond her. With such a rigid opponent-orientation Hegering was rarely in a position to offer cover for any errors of her team-mates. Unfortunately for the two-time World Champions, there were many.

In some situations, the bad positions in their back line were due to incorrect and too early anticipatory movements. Blackstenius and Jakobsson exploited these moments expertly, running into the space these movements left behind. When this incorrect anticipation was paired with excessive opponent orientation from the centre backs, it led to large channels between them. A few of these aspects were visible in Jakobsson’s equalising goal.

Although the Swedes had a far worse platform to build attacks than their opponents, they used it better and quicker and thus created more chances.

Second half

The context for the entire second half changed within 3 minutes of the restart, as Blackstenius gave her side the lead. With the lead, Sweden’s strategy became predictably risk-averse both in and out of possession. In possession they focused on using the goalkeeper, and deeply positioned centre backs to pass time until the German forwards pushed forwards. They would then play long balls, mostly towards the left side aiming to set up compact situations near the left corner. Regaining the ball in these positions under pressure from Sweden’s forwards, Germany found it tough to create controlled situations.

This led to a number of clearances, which Sweden often won in the centre through their double pivot. After securing these, Sweden sought to switch as quickly as possible to Jakobsson on the right, with time and space to use her superb dribbling to drive towards the box.

Voss-Tecklenburg’s side initially played with similar structures to the first half, despite the personnel changes with Magull now playing deeper alongside Popp, and substitute Marozsán higher alongside Schüller. They attempted to use their structure for a riskier build-up, with Popp in particular driving the ball forward at every opportunity. However, they now faced a deeper opponent. Sweden’s wingers, Jakobsson in particular, followed the full-backs, forming back 5 structures.

Germany increasingly tried to progress quickly, with less time for the deeper players to organise the rest-defence as a result. As such, the game became increasingly transitional. Although Sweden didn’t create chances from these turnovers, it meant their opponents started more possession phases after transitional moments, meaning less time to organise their positions. Germany thus entered a cycle of unstable attacks, unable to create danger and Sweden looking more likely to increase their lead. Germany began focusing exclusively on progressing on the wings and crossing, and moved Popp up front in line with this.

They found themselves frequently switching since Gerhardsson’s side had blocked progression on the near wing well. However, they failed to misdirect Sweden’s defensive structure since they constantly played around rather than through their opponents and lacked disguise on long switch passes. Germany’s wide players were thus given no time-space advantage upon receiving in wide areas. Furthermore, the movements of the near players were ineffective, often isolating them by running into the box for crosses. A series of hopeful lofted crosses followed to no avail.

Conclusion

Gerhardsson’s side reached the World Cup semi-finals due to a combination of their well-executed runs, and resolute deep defending of the second half. Germany however, are out in the quarter finals for the 3rdtime in their history. This was mostly down to lacking the right balance between risk and security in build-up, usually playing risky without the right security structures, and too risk-averse when they were well positioned to be stable against ball losses.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen