World Cup: Day 7, scrappy wins for Portugal, Uruguay and Spain

With Egypt knocked out the previous day, Saudi Arabia joined them on day seven as the second round of games for groups A came to a close. Meanwhile, Cristiano Ronaldo took the lead in the race for the Golden Boot as Morocco became the third team to be eliminated, despite a strong showing.

Portugal 1-0 Morocco

Portugal made one change from their 3-3 draw against Spain, with Joao Mario coming into the line-up for Bruno Fernandes. As for Morocco, Khalid Boutaib replaced Ayoub El Kaabi, as did Nabil Dirar for Amine Harit, prompting Nordin Amrabat’s move from right-back to right-wing.

Different Teams, Different Approaches

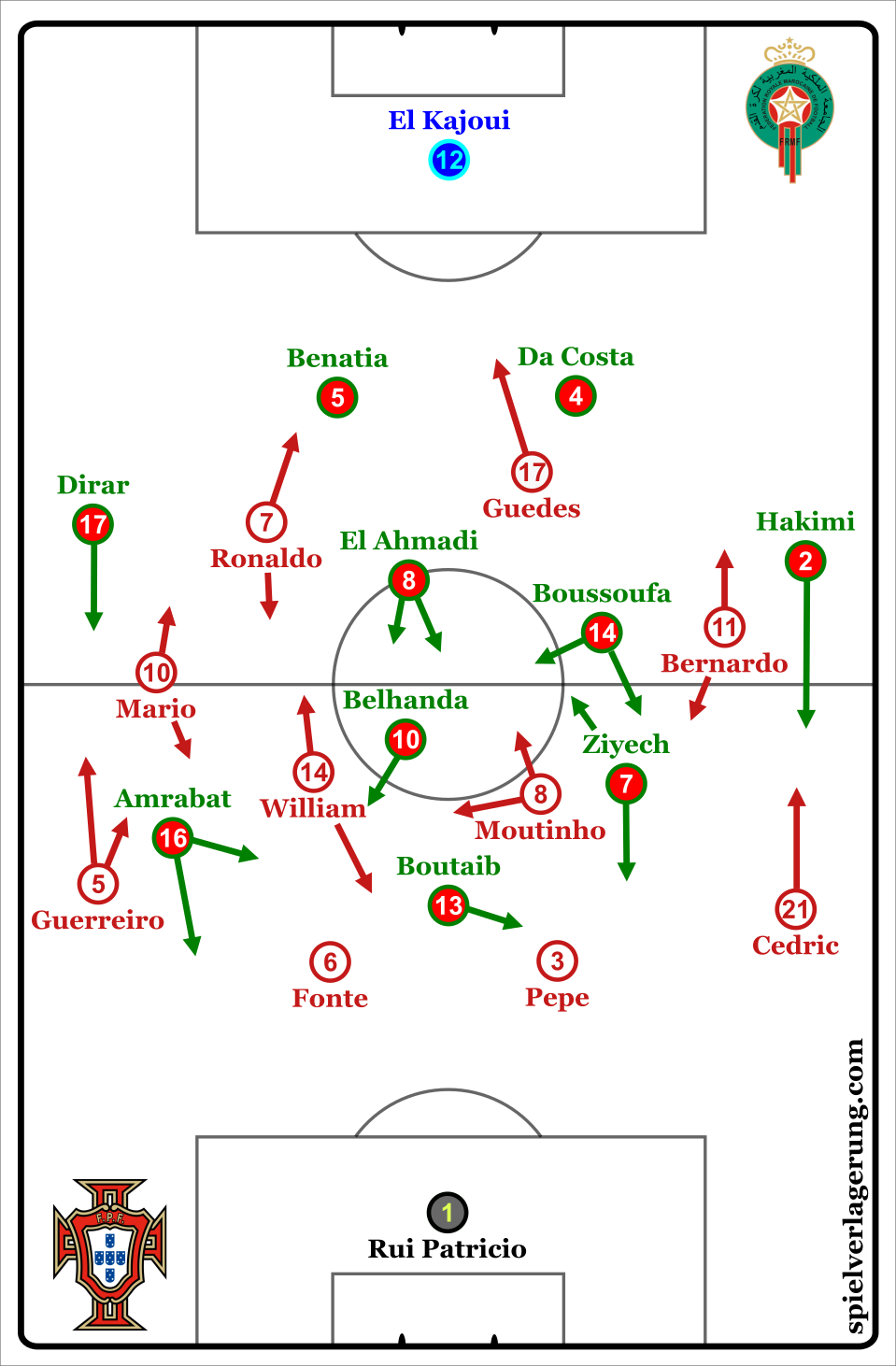

Each team set-up differently for this encounter, with Portugal aiming to pose their biggest threat to Morocco in attacking transition. During Morocco’s build-up, Ronaldo and Guedes had direct access to Morocco’s centre-backs, but didn’t aggressively press them. Mario and Silva dropped to deep positions when following Morocco’s advancing full-backs, whilst William and Moutinho pressed higher than a central-midfield chain of two usually would. They were proficient at disrupting Morocco’s central-midfielders when they received the ball during their build-up, but they left a large space between themselves and their defence. Consequently, Portugal struggling to deal with long balls forward to Boutaib and Amrabat, especially in one-on-one situations, where Guerreiro particularly struggled to defend Amrabat.

During Portugal’s build-up from the goalkeeper, Mario occasionally dropped into the left central-midfield position, with Carvalho in the middle and Moutinho as the right central-midfielder. Whilst Guerreiro was usually in a wide position, he sometimes moved into the left half-space with Mario hugging the touchline. Moreover, Ronaldo sporadically operated in the wide channel when Mario was in the left central-midfield position, and Guerreiro was wide.

However, as previously stated, each team set-up differently, and instead of aiming to counter-attack like Portugal, Morocco’s aim was to aggressively regain and retain possession. They inflicted very high pressure on Portugal during their build-up in a 4-1-4-1 shape, successfully disrupting them for the best part of the match. Belhanda and Boussoufa acted as #10’s, with access to Carvalho and Moutinho, man-marking them wherever they went. Either Belhanda or Boussoufa would also sometimes join Boutaib in pressurising Portugal’s centre-backs. El Ahmadi acted as an aggressive, supportive #6 in pressing to create 2 v 1 situations against the Portugal ball-carrier, whilst also marking more advanced players drifting into central positions such as Bernardo and Mario.

Morocco’s pressing structure during Portugal’s build-up, indicating which Portuguese player(s) each Moroccan had access to.

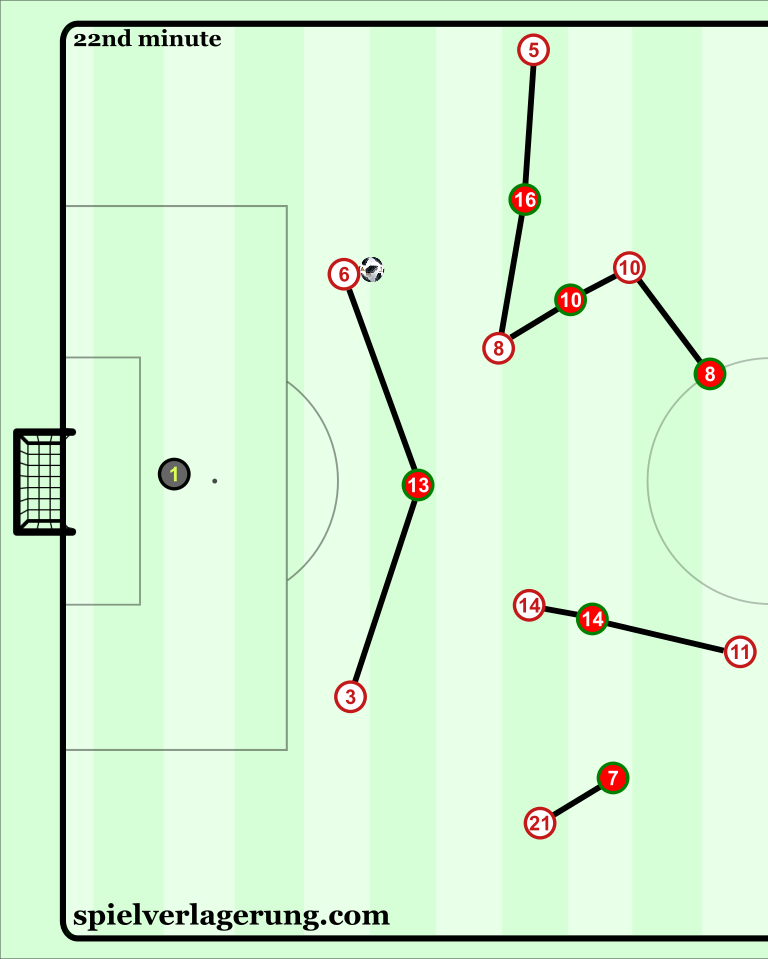

Portugal’s passing execution was poor on many occasions, which was a factor towards Morocco’s ability to successfully regain possession, but Portugal only had two shots between the twentieth minute and half-time, highlighting their limited threat and Morocco’s superiority over them in terms of nullifying their attacks.

Fluid Morocco Fantastic, Yet Fruitless

The positional freedom that Morocco’s midfielder had when attacking was more effective than in their first match against Iran, which was largely due to Amrabat playing as a right-winger as opposed to right-back. In their match against Iran, with Harit playing in attacking-midfield instead of Amrabat, the structure between Morocco’s three attacking-midfielders wasn’t optimal because they had too much positional freedom, creating spacing issues. But it was better with Amrabat as more of an out-and-out winger, as only two of the three attacking-midfielders had positional freedom. Still. I only say ‘better’ because Amrabat sometimes moved away from the right-wing position, on one occasion drifting all the way over to left side of the pitch when the ball was there, which was completely unnecessary. He congested the area, meaning there was no way through Portugal’s defence for Morocco to progress. To sum up, Morocco’s organisation was an improvement from their first match, but remained problematic.

Ziyech operated in a free role from the left wing, moving inside to a more central position, both in attacking phases and during Morocco’s build-up. Consequently, either Boussoufa or Hakimi operated in the wide channel. Boussoufa pushed forward in the left half-space, especially when Ziyech roamed away from this position. Belhanda occasionally did the same in the right half-space, but provided more balance in midfield. He occupied intelligent positions relative to the team’s structure and his teammate’s positions, creating and maintaining connections between them.

Nevertheless, despite their dominance and multitude of goal-scoring opportunities, Morocco somehow couldn’t find the back of the net. Their most dangerous threat ended up coming from set-pieces, where Benatia had plenty of chances, but snatched at most of them. Additionally, Patricio made some great saves, bailing Portugal’s defence out multiple times.

Conclusion

Some may have suspected this match would go this way, with Morocco dominating possession and Portugal posing their biggest threat in counter-attacking situations, but Morocco were unable to convert their superiority in terms of ball occupation and chance-creation into goals. On another day Morocco may have comfortably won this match, yet there are reasons for their lack of success in Russia this summer, such as the lack of a quality centre forward, and remaining structural/spacing issues in attacking midfield. Still, it would be fair to label them as one of, if not the unluckiest team at the World Cup so far.

Portugal on the other hand could very well have found themselves with zero points at this stage of the group playing the way they have against Spain and Morocco. The reigning AFCON champions are now out of contention to qualify for the knockout rounds, but they could yet have a dramatic effect on the final group standings by earning a result against Spain next week, who are set to contest qualification from Group B with Portugal and Iran on the final match-day.

Analysis by GT

Uruguay 1-0 Saudi Arabia

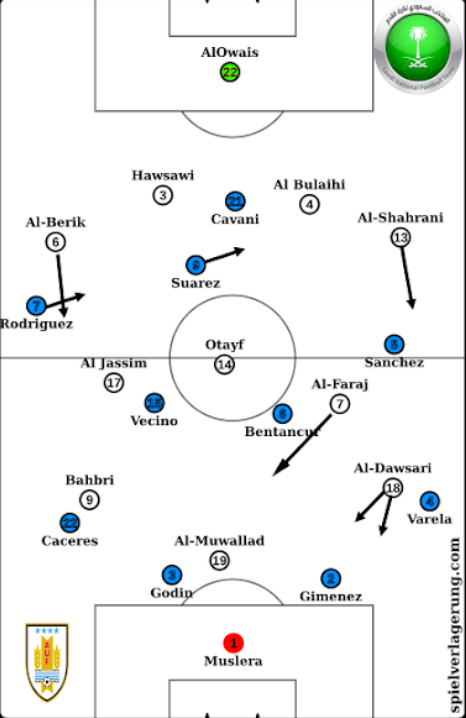

A match that will certainly not go down as one of the greats saw Uruguay join Russia in qualifying for the last 16, and in turn sending Saudi-Arabia home with Egypt. After Uruguay’s late victory versus Egypt on Day Two, Tabarez altered his two wide players, whilst Pizzi made four changes after the harrowing opening day defeat to Russia.

In the end, the match swung on quality. Where Saudi-Arabia’s players lack the top-level ability of Uruguay’s, the South-Americans were able to stumble to a 1-0 victory despite playing poorly. Uruguay are living off perception, to an extent, with a very bad performance against weak opposition being widely misconstrued as “professional and organised”. Saudi-Arabia, conversely, were structured relatively well both with and without the ball, and if not for a bad goalkeeping error, would have earned a point.

Uruguay’s Build-Up Struggles

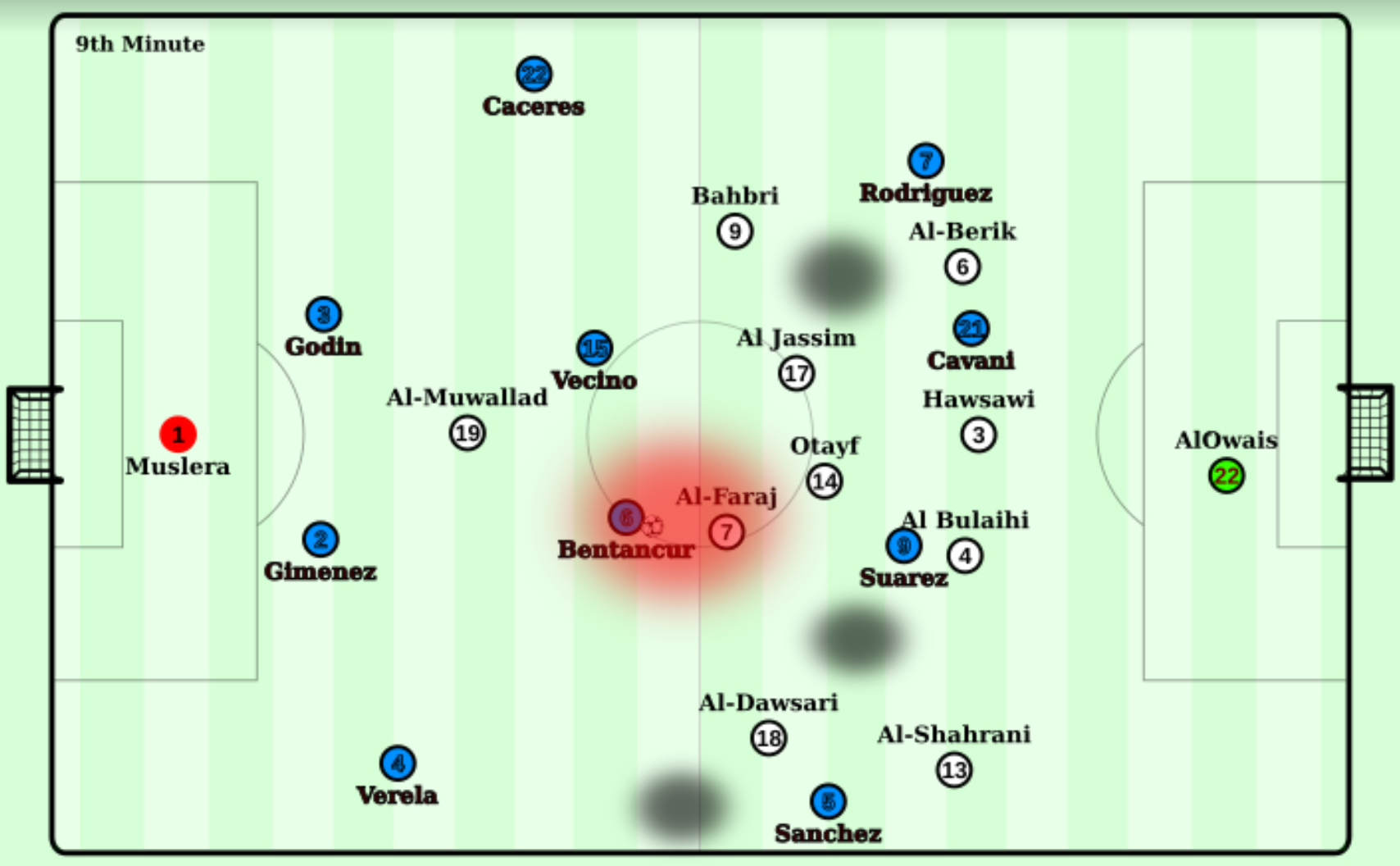

Uruguay spent large swathes of the game in build-up phase two (i.e. with controlled possession in front of the opposition first or second line), yet were routinely unable to penetrate Saudi Arabia’s 4-5-1 defensive shape. Both Bentancur and Vecino positioned themselves in front of their corresponding centre-backs, and asked for an initial pass around the lone pressure of Al-Muwallad. Easily finding success in this 4vs1 scenario, the pair were then faced with a central and passive trio. The two 8s in the Saudi-Arabia structure were blocking halfspace passes, whilst Otayf would block central access to the withdrawn Luis Suarez. Bentancur and Vecino were so narrow when receiving from their centre-backs, that they had no angle to open Saudi-Arabia horizontally or make diagonal passes in between their shape. It would have been far preferable for Gimenez and Godin to bring the ball forward against the one-man Saudi-Arabia press, and for the two 6s to then position themselves in the halfspaces to either receive the ball or widen the position of the Saudi 8s.

In the event, there was absolutely no presence inside the Saudi midfield shape due to Rodriguez and Sanchez remaining wide for most of the first-half. Coupled with the deep positions of Uruguay’s CBs, thus unable to open the halfspaces wider, such poor positioning resulted in Saudi-Arabia being able to turnover possession far too often. This was wholly unnecessary, as on the two occasions Uruguay inverted their wingers to attract their full-back, and made an extremely simple wide rotation with the full-backs running into the space in-behind, they were able to penetrate the Saudi back-line comfortably. With Cavani and Suarez typically able to use disguised movements to make space in the box, it was unfortunate Uruguay were not able to break the defensive line more often.

The lack of presence within or high-enough around the Saudi-Arabia shape (denoted by the black shadows) made breakthrough very difficult for Uruguay.

The second half showed more purposeful use of the spaces in Saudi-Arabia’s structure, with Suarez often coming into the left-halfspace to allow Sanchez to occupy the right one. This created an asymmetrical 2-4-3-1, and allowed Bentancur to make disguised passes around the sides of Otayf in the 6 position. The introduction of Laxalt increased such options, but really resulted in little due to no connective movements from the full-backs or 6s.

Disappointing Counter-Attacks

With the supreme relative quality of the Uruguay strikers, any open spaces should have been penetrated a lot better than they were. Saudi-Arabia often over-occupied wide areas, with their three attacking midfielders roaming across the pitch joined by full-backs and at times one of their 6s. When doing so, a lack of quality technique, bad spacing or bad decision often resulted in a turnover, and then zero counter-pressing. However, Uruguay were unable to counter-attack efficiently and Cavani or Suarez often became isolated with no support from the full-backs, whilst Vecino and Bentancur had clearly been instructed to not join counter-attacks but to provide a base for rest-defense instead. This meant transitions relied largely on the individual quality of Cavani and Suarez, yet the former was almost able to pull off the extraordinary on two occasions; one resulting in a saved shot, the other a perfect cross headed over by Sanchez.

Deceptively Poor Mid-Block

Despite some lazy comparisons drawn in certain quarters, this Uruguay side are not Atletico Madrid. A defining reason for this is a relatively weak mid-block. Whereas with their club side Godin and Gimenez play behind a compact, clever and aggressive midfield four-chain, Uruguay’s was nowhere near the same level in this game. With the ball on the opposite wing or halfspace, the ball far winger positions himself too wide and thus allows diagonal passes on the outsides of the two 6s. Godin and Gimenez are loath to step into this space, and whereas with Atletico Madrid their full-backs on either side begin so compact that the distance to intercept in this space is small, for Uruguay Varela and Caceres begint too wide to be able to win the initial contact in this space. Therefore, when the ball was received by one of the Saudi-Arabia players entering this space, the wide in-behind space often became open as the full-back attempted to contain combinations or dribbles towards goal. The intense pressure Atleti place on the ball carrier with close staggering was also non-existent, and better sides, who offer good positions and a generally high technical level (i.e Spain, Argentina) will certainly score goals against Uruguay if they meet in the latter rounds.

Although, Uruguay did offer a resolute low-block on the edge of their penalty box, with Vecino and Bentancur no more than 5-6 yards infront of Godin and Gimenez. If they are able to establish this defensive phase quick enough, they will be able to withstand pressure. It is, however, before this phase that the concerns exist.

Saudi-Arabia: beautiful yet flawed

Just as AL wrote after their opening day defeat, Saudi-Arabia’s intensely possession-based offensive game has as many highlights as flaws. Despite eradicating the errors we saw against Russia, they were still unable to really penetrate the Uruguayan defense due to really poor spacing. Although the three attackers behind Al Muwallad largely begin in the pockets in between the midfield and defensive line, they will often condense the ball-side to look for intricate combinations and dribbles. This often leads to very constricted positioning, which then requires a switch into the opposite side and an unlikely 1vs1 opportunity. The slender build and weak ball-shielding of their attacking players meant 1vs1 situations were rarely favourable.

Therefore, when the three players who, tended to roam fairly randomly behind the midfield line, decided to come into the line to receive, they usually were dispossessed. In a team in which you possess quicker, stronger and more agile midfield players, entering the midfield line can be a superb way to attract pressure in order to break the line through a set or turn. When your players are weaker in the above attributes, entering the line in order to receive is not ideal.

Al-Muwallad, for his part, impressed with consistent runs in-behind, thus largening the pocket line (space in between defense and midfield) for his teammates to receive. This, however, was rarely followed by a movement into this space, and so his run was redundant. Indeed, when a pass was played directly to him, in-front or in-behind, he was either not support by connective movements or unable to hold the ball against the physical pressure of Gimenez or Godin.

Conclusion

Saudi-Arabia exit the tournament with a final game against Egypt offering them another chance to display an impressive style of play. Despite having weaker players than most other countries, they have certainly brought an interesting element to this tournament, showing OK positions, admirable confidence with the ball at their feet and some nice technique.

Uruguay will be more than happy to win this match 1-0, and would absolutely take this result in all of their upcoming matches. However, with the identified in-possession struggle seen in this game, as well some potential fallibilities in some defensive phases, they will surely become unstuck against superior opposition.

Analysis by JB

Iran 0-1 Spain

The final game of the day saw Iran take on Spain. Having drawn in their first game against Portugal, Fernando Hierro’s men knew that defeat would see them crash out in the group stages for the second consecutive World Cup.

An Iranian wall

While many teams have attempted, to sit and absorb a Spanish onslaught, few have managed to frustrate them as well as Iran. With their 4-5-1, Carlos Queiroz’s side stayed in a low block in the first half, limiting the space in behind for Spain to attack. Furthermore, with their low line of engagement for pressing, Iran kept a great degree of compactness, giving them access to almost every Spanish player in the attacking third.

This compactness was adequately maintained, despite their defensive behaviours. With their many man-orientations in midfield, Iran ran the risk of being dragged out of their cohesive defensive structure. This was the case particularly on the flanks, where the Iranian wingers would mark the Spanish fullbacks, easily falling into a Mourinho-esque 6-3-1. However, the intensity in their pressing movements, and the covering thereafter, made it difficult for Spain to exploit the open spaces. This intensity allowed them to pressure the receiving player immediately, forcing them out to the periphery.

Present and clear possession play in transition

Iran’s play in the rare moments when they had possession was impressive in its own right. Through some dynamic dribbling and small-scale combinations, they were occasionally able to bypass the immediate Spanish pressure. This gave them access to the larger spaces in front of Spain’s backline, forced back by a lack of pressure on the ball and the threat of runs into depth.

In this area, the Iranians supported their forays into their opponent’s half well. Central runners lend support to the ball-carrier while the fullbacks, particularly Rezaeian on the right, offered an outlet to escape pressure. From here they would look for crosses to the aerially menacing Azmoun, aiming to avoid matching up with Ramos or Pique.

Carlos Queiroz’s side continued this focus in their set-pieces, with free kicks and corners forming a strong part of their approach. Taking their time with these, Iran could disrupt Spain’s rhythm as well as run down the clock. By dribbling in pressured situations, Iran drew a number of fouls with minimal contact, further frustrating the Spanish players.

Laboured Spain

Spain’s customary 4-3-3 saw two changes from the side that drew 3-3 with Portugal. Lucas Vasquez replaced Koke and took up the right wing berth, pushing David Silva to the right 8 position, while Dani Carvajal made his first World Cup appearance in place of Nacho at right back.

Hierro’s side continued their flank focus in possession, particularly on their left side. Iniesta and Silva acting quite wide and in their respective halfspaces, combined with Alba and Carvajal advancing, gave rise to wide triangles, through which Spain attempted to create a breakthrough. However, with short distances between players in Iran’s last line and little occupation in advanced areas, breaking through there proved initially difficult.

Failing this, Spain tried an alternate route. Such was Iran’s total commitment to defending, Azmoun was most often working around Spain’s central midfielders. This removed the need for an excessive Spanish rest-defence, allowing Ramos and Pique to step forwards next to Busquets. From these positions, the centre backs tried quick, direct switches to the opposite flank, particularly to the right side after struggling with Iranian congestion on the left.

These switches were rarely successful, however. Iran’s wide-reaching back line, with their man-marking wingers, maintained access to Carvajal, challenging immediately. Furthermore, Spain lacked coordination in these moments, from the efforts to reduce Iranian cover of the far flank, to the movements to occupy it to receive the switch. These both served to minimise any dynamic advantage Spain could have gained through switching the ball such a distance at speed.

Contrasting sides

While Spain predominantly looked to the flanks initially, their right and left sides acted in considerably different ways. On the right, Vasquez, Silva, and Carvajal were structured and coordinated, with the Real Madrid pair timing their movements well to occupy the area opened in the halfspace by Silva whilst also giving depth. From here, though, Vasquez had a hard time progressing play further due to the large distances between him and any of the left sided players. With Diego Costa acting mainly left of centre, Vasquez was forced to bridge this gap to his supporting teammates with small dribbles in an intensely compact area, to only a small degree of success.

On the left, the situation was considerably more fluid. While Iniesta acted consistently in the left halfspace in the first half, with Alba pushing up on the flank, Isco interpreted his role far more freely. The Real Madrid star drifted far from the left wing, popping up in various positions along the first line, without greatly affecting the Iranian defensive block. With Spain often having Silva, Iniesta, and Isco in the first line, their occupation of the spaces between the lines was sorely lacking. Vasquez and Carvajal occasionally moved infield to remedy this, but require strong support structures to help them progress possession.

As in any team, the profiles of the players in each position greatly affects the collective performance. In this case, Isco’s profile on the left differs from Vasquez on the right. While Vasquez held his position on the flank, making considered moves into the halfspace when the ball reached Silva to provide a central threat and give room for Carvajal to push up on the flank, Isco’s movement and positioning was far more haphazard, ball-oriented, and ultimately less effective. While he is undoubtedly talented, and almost perfect for a small overloads and quick combinations team, in this respect, Isco is far more well-suited to Real Madrid’s game than he is Spain’s at this moment.

Second half adjustments

The second half saw Hierro slightly alter the dynamic of his wide triangles. Even slightly before the break, Vasquez was already acting more in the halfspace than just simply as a touchline-hugger. Additionally, Carvajal moved even more often diagonally into those positions, pinning the cover shadow of an Iranian midfielder and forcing the 6 to consider moving across to help. Silva’s positioning was considerably more advanced as well, also looking to receive between the lines from Pique and even Isco when he roamed that far. The left sided triangle was also adjusted, but in a different way. Iniesta and Isco alternated positions in the centre, connecting them more effectively to the right side, even if only in withdrawn areas.

Meanwhile, Iran adopted a more proactive approach, especially once they had conceded. Engaging higher up the pitch in more of a midfield block, Queiroz’s side emphasised some of the problems in Spain’s spacing through their higher pressing. While this gave them some promising counter attacks, it also gave Spain more room to play through, as they so expertly managed on a number of occasions. Their continued counters and set-piece focus bore great chances as they turned up the pressure in pursuit of an equaliser.

Ultimately, however, Spain managed to hold on for their first victory of the tournament. Costa’s winner was perhaps symbolic of the Spanish performance – scrappy, but good enough in some way to get the result.

Analysis by AL

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen