World Cup: Day 4, Mexico shock Die Mannschaft

Day 4 capped off an action packed weekend of football over in Russia, with Serbia defeating Costa Rica and the Swiss nicking a point off of the favored Brazilians. However, Germany were toppled by Mexico in what is the upset of the tournament thus far, and the focus of this daily recap.

In our team previews of Germany and Mexico, each of the authors had different impressions about what was to come from each team. The defending champions were met with fears that they could be exposed on the counter, with that the selection of Löw’s favorites leading to poor on field dynamic and stale attacks that become reliant on individualism. I personally viewed Mexico as one of the most interesting teams of the tournament, demonstrating tactical flexibility that no other team in the competition can replicate as well.

However, I still had doubts that Mexico could come away with a result. Against higher level opponents, too many issues surrounding their pressing existed, and a side as good as Germany in midfield would expose them unless Mexico made changes. It’s Juan Carlos Osorio though, of course he made changes.

*If you are interested in reading, CE analyzed this match for spielverlagerung.de as well*

Germany 0 – 1 Mexico

Due to Juan Carlos Osorio’s rotational policy and at times eccentric team selections, the eyes were on the Mexican team sheet to see what he possibly have up his sleeve for the most important match of their group stage campaign. If they even got one point out of this match, El Tri would be in an excellent position to advance into the knockout rounds.

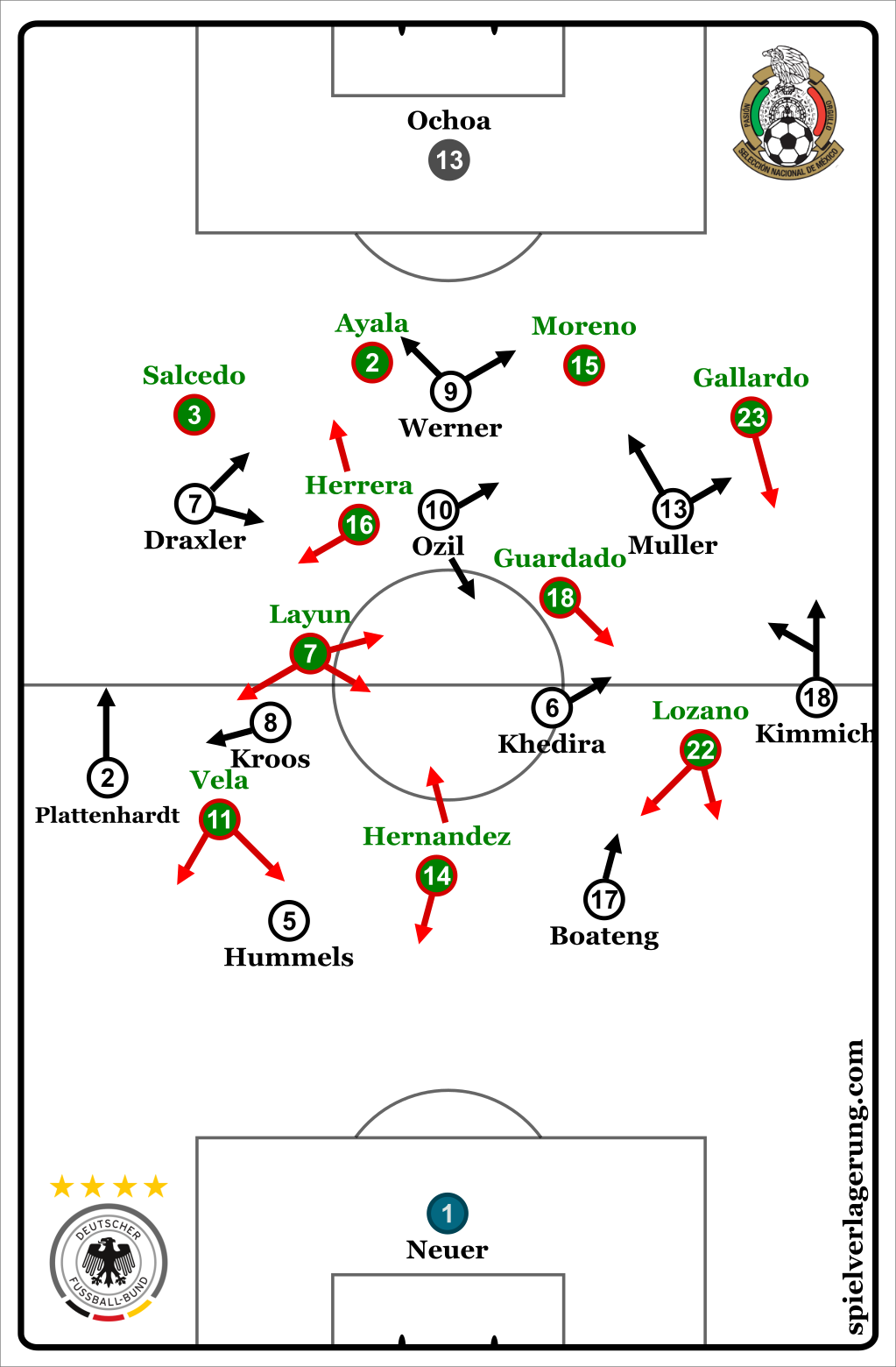

Mexico’s team selection was not comprised of many surprises individually, and the choice of a 4-3-3 was in line with what Mexico has used in the majority of Osorio’s tenure. Across the back, Carlos Salcedo was put back to his right fullback spot that he occupied for much of qualifying, with Hugo Ayala and Hector Moreno forming the central partnership. Winger converted to fullback Jesus Gallardo slid in at left back. Miguel Layun in midfield would have been a surprise if you had woken up from a year-long coma, but he had featured there in all of Mexico’s 2018 friendlies. The front three was as many expected.

Germany’s team selections were void of big surprises. In their 4-2-3-1 system, Julian Draxler was preferred over Marco Reus for the left sided attack. Jonas Hector was left out with Plattenhardt being selected instead. Besides those choices, many of the same names from the Löw era were front and centre.

Osorio’s Approach – Germany’s Responses

This Mexican team were duly prepared for this match, having faced Löw’s Germany last year in the Confederations Cup semifinal, where they lost 4-1. That match was notable in particular about how Mexico controlled the majority of possession during the match, with their midfield having some quite long spells of possession at times. However, early on Germany’s press led by Timo Werner and supporting by his front was too much for the Mexican contingent to handle due to their intensity in pressuring the ball and blocking off midfield solutions with their cover shadow. Because of these the lack of coverage from the centre in rest defense and overly ambitious positioning from Mexican fullbacks, Germany’s transitions when they won they ball were lucrative, being the source of their goals on the match. With better players coming for their return to Russia, Osorio opted to change his approach in the hope for three points.

For this match, Osorio wanted to turn the tables. Rather than have his midfield attempt to outplay the German contingent in their typical positional possession, Mexico served Germany a dose of their own medicine by emphasizing transition play with their attack. With Lozano and Vela on the left and right wing respectively, they were the first targeted passes for Mexican possession, with their rapid dribbling the primary means of their attacking developments. With Germany fielding Joshua Kimmich and Marvin Plattenhardt, these fullbacks contributed to attacks higher up the field and be primary sources of width, with Muller and Draxler moving toward the halfspaces to the sides of Mesut Ozil.

The German left side resembles a strategically important area for the team, as metronome Toni Kroos operates in the deeper portions of their halfspaces there. With Julian Draxler moving interiorally as Plattenhardt moves higher alongside Ozil and Werner’s inclinations to move toward that side, many attacks are initiated by the Real Madrid stalwart. Due to this dynamic on the left side, it was difficult to fit in Leroy Sane into this stacked German group, since he is unable to get the same kind of isolation he faces at Manchester City in this kind of team structure where Kroos is king.

The tweet below from our own CE translates to: “Löw will not change the side balance. Toni Kroos pulls the strings over on the left side of the pitch. This is set in stone.” Kroos’ importance is to this team is understood, and Osorio’s defensive strategy was set on limiting the influence of one of the best midfielders of the last decade.

Löw wird an der Seitenbalance nichts ändern. Toni Kroos zieht das Spiel über den linken Halbraum auf. Das ist in Stein gemeißelt. https://t.co/crqam1ZtVx

— Dr. Constantin Eckner (@cc_eckner) June 4, 2018

To limit Kroos’ influence, Carlos Vela was assigned to the task of man-marking, hence diverting passes that normally went to Kroos away from him. In the early minutes, Kroos was unsure of how to deal with this problem or if he was even man marking, drifting toward the right of the pitch instead of his customary left to see if Vela continued to track him (spoiler alert: he did). To compensate for the dead space that ensues because of such man-marking, Miguel Layun was slotted as the right central midfield, collaborating with Carlos Salcedo for defensive efforts on the right side.

Layun, typically a fullback, routinely placed himself in positions in the halfspace to maintain access to the wing and the centre. His high stamina levels, good closing speed, and fantastic positional discipline made him and excellent fit for this role. With Salcedo’s nearest player Draxler drifting toward the middle during possession, his experience as a central defender comes in handy for defending interior zones and having the physical and intellectual profile to manage these dynamic shifts.

Hirving Lozano primarily tracked the deepest player down Mexico’s right side. Hector Herrera and Guardado each occupied quite central starting postions against the ball, with Guardado stepping up toward Khedira as he checked deeper to prevent Germany from establishing possession with their midfielders. This left the ball primarily on the feet of Hummels and Boateng, two gifted defenders in possession, unsure of how to solve the difficult situations of not being able to comfortably play into the midfielders just in front of them.

Carlos Vela is man-marking Kroos here, and with Mexico’s spatial coverage of the centre, Germany are compelled to develop their attacks down the right wing.

Mesut Ozil began to move deeper in possession in support, with Kimmich moving higher in response. From there, Germany had some attacking sequences form on the right side that were comprised of Kimmich’s isolation on Gallardo, but Mexico dealt with these wide attacks well. The end result either was some kind of deflection for a corner kick, an intervention from the support of Hector Moreno, or easy saves for Ochoa.

This midfield behavior led to some large gaps in between the attacking midfielders and Werner, leaving room for him to run behind as he targeted these sequences. Germany had some close opportunities originate from this, particularly as Werner moved from left to right in between Salcedo and Ayala. Kimmich effectively functioned as a hybrid between his fullback spot and a central midfielder, moving in relation to the angles of Thomas Muller, and if Khedira was behind Kimmich as Muller was wide, Kimmich slid into midfield just beneath Mesut Ozil in possession.

Yet Mexico were primarily concerned with marking rather than pressing right away. Mexico’s front players had particularly struggled with pressing going into the tournament, often being late with their coverage of the centre alongside being inconsistent with their intensity. For all the variations and interchanges that the Germans had, Mexico were able to adapt and have adequate coverage of the most threatening options for each pass.

Best Never Rest (Defense)

As Germany looked to find ways to attack down the right hand side, the central stability of their system disappeared. On the left side where Kroos operates, Khedira performs as the balance if the ball is lost and Germany isn’t left as exposed in attack due to Kroos deeper coverage of the fullback. With the attacks now moving down the right side, Plattenhardt didn’t adjust his positional behavior very much, still moving higher as Draxler moved inside. Kimmich, a serial recipient of the ball by this stage, involved himself more and more into the attack as the first half wore on.

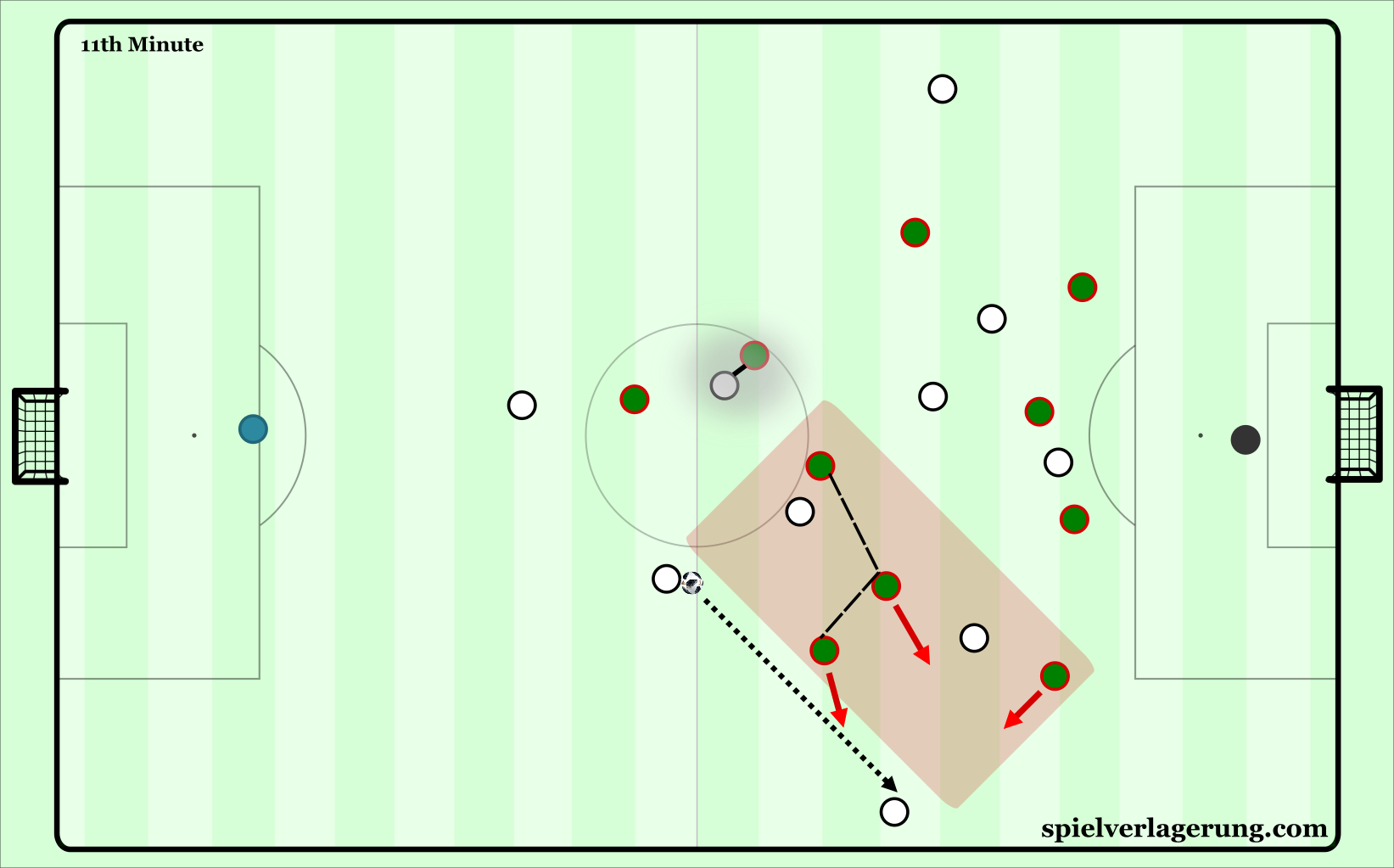

With these two joining the front four, shape variants among them formed, but most commonly it was a line of five and Werner highest. This left the wings greatly exposed, creating the perfect storm for Vela and Lozano to wreak havoc on the World Champions. If the centre was better covered, these counterattacks would not have been as dangerous for the Germans to concede in the first place.

Due to Germany’s poorly structured rest defense, Hector Moreno easily passes to Hernandez to initiate the counter attack since no German player is occupying the centre. With Lozano sprinting down the left wing, Mexico takes the lead through him.

There were some rough moments from genuinely world class players in this sense. Kroos instead still was positioned in his customary left halfspace, even as Khedira shifted toward the ball during rightward attack development. It was almost as if Kroos was on some kind autopilot while he was distant from the ball that didn’t lead to him recognizing he had to move centrally for stability, and this gap between Kroos and Hummels resulted in ripe conditions for Mexico to counter. The six and eight were often too high or too wide to help with defending transitions, leaving Boateng and Hummels stranded. When Hummels thought the centre wasn’t covered well, he moved up into midfield to pressure balls that he had no little chance of actually winning, leaving his partner to deal with the problems himself. It was astonishing to see how open Germany were because of their poor transition structure and the subsequent counters they conceded.

Mexico also used German set pieces as a moment of great potential for their counter attacks. With Germany having paid extra focus into standards in the last World Cup, the attention to these situations would be high once again. Yet by committing their best defenders forward, once the ball is cleared Mexico face the possibility of attacking both large free areas and inferior defenders to what they normally come across during the run of play. These situations created high potential attacks, but these were not converted despite their promise.

Given the amount of opportunities that Mexico had on the break, it was surprising that they didn’t score more than once. Only the execution was lacking from them, as all of the movements, dribblings, and perception-action coupling for passing decisions were essentially spot on right until the final third. Once they were faced with Manuel Neuer, it was almost as if they froze when the titanic goalkeeper braced himself for the oncoming shots. Javier Hernandez stood out from an execution standpoint, this time in a negative way. Both Vela and Lozano were excellent, but Hernandez’s passes and receptions of their balls were just off, leading to promising chances becoming wasted.

As fantastic as Vela and Lozano were on the break, Chicharito was excellent in a different respect. No other centre forward in the squad could’ve possibly played the role he did for them, which was remarkably understated in the immediate post-match analysis. What Mexico’s all-time leading scorer did so well was in respect to his movement as possession was recovered.

While the rest of his were defending, Hernandez stood in an offside position unaccounted for by the German centre backs. By being behind them, he became an immediate point of focus for Hummels and Boateng once the ball was recovered. The former Manchester United striker jumped back onside in the nick of time doing two possible things. Either Chicharito recycled his runs back onside to look for balls into depth, or he checked into the space in front of them looking to lay the ball off onto the nearest midfielder. These movements depended on whether or not he was able to get the ball off of his teammates.

His recycled runs were breathtaking, taking Hummels and Boateng with him out of fear of him beating their offside trap and getting a clear path to goal. These movements occupied the Bayern tandem so much that Vela, Lozano, and even Miguel Layun were able to sprint toward the German goal with almost no pressure applied to them. Even if Chicharito was playing with a piano on his back, he still was contributing to the music by working the pedals and modifying the composition of the sounds being made by the keys.

At the beginning of this decade, the Bundesliga was the home of the best counterattacking across the world’s top leagues, with Germany in particular building some of the finest talents for this style of play. Throughout time, teams have come up with solutions to prevent these potent moments, but the national team of all sides should be able to apply at least one of these solutions adequately. Another central presence instead of the pseudo-centre player that is Draxler would’ve improved occupation, forcing Mexico wide with their counter attacks rather than them parading through the heart of their team.

Yet they weren’t equipped to do so. Draxler and Ozil offered close to nothing when it came to counterpressing when possession was conceded high up the pitch, and for all the running that Muller and Werner do, their counterpressure attempts were negated by the ex-pats since they rarely responded to players changing their movements when covered by a cover shadow. At times, the Germans also appeared fatigued by the possibility of counterpressing, a couple of steps late and unable to sufficiently apply the same level of intensity as in years past. Ozil’s reaction when getting dribbled by Lozano before his sums it up best – doing enough of the work to make it look like they were contributing to the cause, but when placed into the actual difficulty of the situation, they couldn’t keep up with the energetic Mexicans. The roles had been reversed from their last encounter a year ago.

*credit to @Dahounic for the joke as the header for this section*

Pressing Issues for Germany

Painting Mexico’s attack as entirely transition based isn’t fair to El Tri, who held possession for considerable spells at some moments in the game. You could hear the cries of “Ole!” when Mexico began to move it around the back to establish control and put their strong possession play to use. The German force did not pressure in the same manner as they did a year prior in Sochi.

Mexico hardly looked to build from goal kicks or in deeper areas, mainly looking to build if possession was regained somewhere around midfield. From here, they passed back when Ayala and Moreno dropped back. Germany would have to move up their lines to initiate synchronized pressure, leaving Werner chasing on his own at times without help from the line behind him.

There were instances where Mexico did build up short from goal kicks, but these were in quick succession of the ball leaving the field of play and not permitting Germany to set up their press in due time. Germany still did press in a man-oriented fashion from these situations with the expectation that their intensity on the ball would create errors from the Mexican back line.

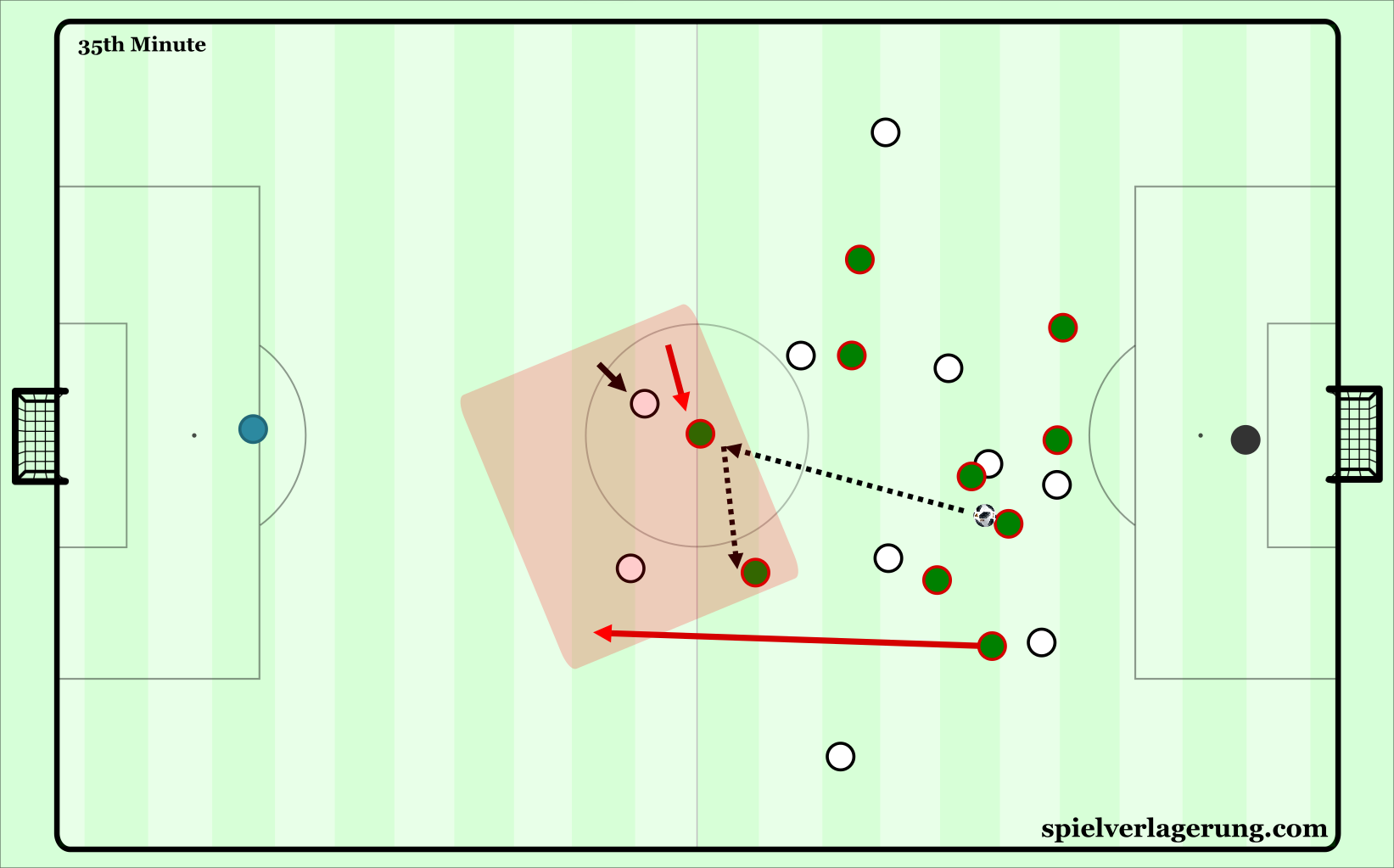

Contrary to these expectations, El Tri were remarkably composed in these instances, moving the ball in fast sequences with strong supporting angles away from the pressure being formed consistently. To break these man-orientations, dribbling was used to get away from the player pressuring the ball. Once the first guy was beat, each subsequent man had to leave their marked player to apply pressure to the ball. Plaudits go out to Hector Herrera for a magnificent display in this regard, appearing unstoppable on the dribbling against the archetypes of modern pressing.

Germany’s man-oriented high pressing was no match for Hector Herrera, skillfully evading their pressure throughout the match.

Even in the first possession of the game existed some red flags about how man-oriented Germany were. Hector Moreno receiving the ball from Ayala, each of the centre midfielders slotted in their respective halfspace. All Hernandez had to do was simply check into the midfield, where he was able to receive the ball with no pressure and pass the ball off to Carlos Vela, who created an overload by moving from right to left for that sequence of play. Hummels had to leave Chicharito running into midfield to account for Vela, the first of many difficult situations the Germans found themselves in over the match.

The Germans did not spend a great portion of the match in states where they could sufficiently apply their high pressure because of the amount of possession they had. During the times where it was applied, there were still issues surrounding the man-oriented nature of it and the reactions of second and third defenders following ball pressure. Mexico were skilled enough to maneuver these situations, and do so whilst making it look effortless at times.

Second Half Trends, Mexico deep block

The beginning of the second half saw Germany have even more possession than in the first period, Mexico resigned to dropping deeper to deal with the numerical onslaught that Germany began to commit toward attacks forwards. Hummels and Boateng were more attacking minded as they stepped up into attack, first to receive passes from midfield and force their opponents to retreat as they dribbled forward, eventually becoming targets of some aerial attacks.

Osorio was the first manager to make a personnel change, introducing Edson Alvarez for Carlos Vela. At the time, this move was a head scratcher to many, considering Vela was a prominent figure in Mexico’s counter attacking exploits that appeared to still be on. Alvarez moved into central midfield as the six. Miguel Layun was placed higher as a right winger, with Herrera taking his old place.

Given the changing dynamics of Germany’s attack, Alvarez was an extremely intelligent change. Germany’s attacks put more players in front of the backs as they overloaded the ten spaces. Without the numbers to cope, this provokes the center backs to move up to intercept passes, cover spaces, etc. In the moments that these centre backs step, small gaps form in the defensive structure that Germany would hope to exploit by moving into them or playing passes surrounding that space. Alvarez can drop in if a German attacking midfielder moves into the forward line and not feel totally out of place since he is a fullback normally for Club America. If it were Herrera on the other hand, that process would be more lagged and questionable.

Marco Reus was substitution number one for Die Mannschaft, taking place of Sami Khedira as Mesut Ozil dropped deeper. Or sort of. Now Germany began to move all their pieces to the front in the quest for their equalizing goal. Kimmich almost functioned as a striker, Boateng and Hummels the only sources of central cover, and Kroos being the lone “midfielder”. It was chaotic as Löw wanted as many numbers in attacking spaces as possible, but at some moments even the players didn’t know what was going on and had to ask the manager what the structure was, with the players unsure of what roles they were occupying in search of their equalizer. To make sense of it, it was an ultra fluid 2-1-7 formation with the 2 dribbling forward whenever there was not pressure occupied.

With seven players to defend higher up against an opponent as good as Germany, Mexico were confined to defending deep to manage the barrage of attacks. Osorio’s last two adjustments were defensive resignations that they were going to be on the back foot and have to cope with a lot of attacks. Raul Jimenez took place of the goal-scoring Lozano, his strong aerial ability a huge asset for defending set pieces. The final adjustment was as functional as it was romantic: Rafael Marquez, an icon for passing centre backs able to play holding midfielder, entered for Andres Guardado. This marked his presence at five World Cups now, being a captain for all five of them.

Mexico now formed a 5-4-1 deep block, Alvarez now sliding into centre back. For all of the theoretical threats of defending deep, one of the things low blocks accomplish well against strong opponents is constricting the space they have to be able to create passes or shots on the dribble, alongside limiting the room to run in behind for possible sources of penetration. This leads to teams being resigned to crossing from wide areas because of the central congestion in addition to the limited territory for quality attacking play.

Mexico’s 5-4-1 block to close out the match. This deep block not only congests the amount of space for Germany’s attackers near the penalty area, but also provides a shield for shots on Ochoa’s goal and multiple defensive reinforcements for last ditch challenges.

Who better to bring on for crosses than Mario Gomez, right? That’s exactly what Joachim Löw did, with Plattenhardt coming off and having no left back whatsoever. With Julian Brandt coming for Werner with five minutes left, it truly became a 2-1-7 in shape, as Brandt somewhat occupied the kind of positions a left back would. He managed the closest chance for Germany, a well struck volley that went just wide of the post. After a lengthy period of deep defending with temporary aids from punts, long balls up, and drawing fouls, Mexico had secured the three points, to date their important win in the Group Stages of the World Cup.

Conclusion

This is Juan Carlos Osorio’s magnum opus of his career so far. Of course defeating the reigning world champions is a big feat for any coach, but the way and manner that Mexico competed against Germany is nothing short of amazing. They routinely put Germany into frustrating situations and capitalized on their collective weaknesses, which were surprisingly in the area of transition.

In the preview of Mexico, one line that I wrote stands out to me even further after this victory, which reads “There is so much that cannot be predicted with this Mexico team, whether it be their starting selections, how they will move forwards, the volatility of their transition game, or their halftime adjustments and substitutions.” This match reflected that line almost expertly, with their main manner of attacking not predicted by many, transitions bordering on excellence without the product to show for it, and their at the time puzzling substitutions which succeeded.

Going into this match, I had never envisioned Osorio planning to defeat the Germans in this capacity. His lines going into the press conference gave the impression that he would try and outplay Mexico with possession. Having seen about twenty or so matches from his tenure, I have seen Osorio implement many systems and ways of playing. I hardly saw this way of playing coming, yet on reflection, it was the best possible combination I could have ever envisioned for this game. It addressed many of the individual and team weaknesses yet mixing them with the strengths of his players and what they could realistically achieve. For the Germans, they seem to have understood the reasons why they have lost. Understandably so, the media will be out for answers and make immediate judgment calls. Löw’s team were a step behind in many respects, but Guillermo Ochoa made some great saves that other goalies in this tournament may not make. Of course there should be some concern, but after the Germans regroup, they still have a strong chance of progressing. Where things get interesting now is what happens if Germany finish second, as a World Cup final rematch from 2002 vs Brazil could be on the horizon.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen