Allegri beats Pochettino in 4 minutes

… but it took some warm-up time in a game with interesting interactions that proceeded in different phases.

Phase 1: Advantage Pochettino

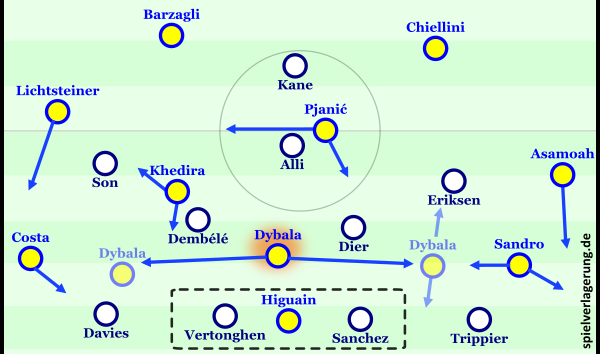

Both teams started with well-known alignments. The hosts from North-London generally showed the usual 4-2-3-1. Hugo Lloris played between the sticks behind the established back four of Kieran Trippier, Davinson Sanchez, Jan Vertonghen and Ben Davies. Erik Dier and Mousa Dembélé started in the double pivot. The attacking line of Christian Eriksen, Dele Alli and Son Heung-min was shifted slightly to the left because of the more central role of the Dane, like in previous matches. They were able to compensate this through the distinctive evasive movement from star striker Harry Kane.

Juventus countered with a mixture of a back three and a back four. Andrea Barzagli filled a role between full-back and half-back. Next to him were Medhi Benatia and Giorgio Chiellini. Alex Sandro, meanwhile, played a role between full-back and wing-back on the left. On the opposite wing, Douglas Costa positioned himself higher than he would have done as a wing-back in an actual back three. In midfield, Miralem Pjanic clearly played the deepest position. Box-to-box players Sami Khedira and Blaise Matuidi supported him as No. 8s. Paulo Dybala started behind Gonzalo Higuain, the only true striker.

Both teams began the match running at opponents high up the field, which resulted in quite a lot of long balls being played in the early goings. That’s a feature of Tottenham Hotspur: To start games using this approach they often try to either score an early goal (as they did against Manchester United in the Premier League) thanks to their presence in attack, or to break the rhythm of the opponent until intensity drops and Mauricio Pochettino’s team can take control over the game thanks to their impressive combination play. Regardless, they aim to push the opponent back into his own half.

Juventus, however, tried to spoil those plans and marked the build-up play of the hosts. They partly used very obvious man orientations in that quest. Dybala and Higuain went towards the two centre-backs, even if the first pass was often allowed. Douglas Costa covered Davies and only moved more towards the centre or backwards when he was on the ball-far side. Khedira followed Dembele with Matuidi doing the same with Dier–even when those two moved backwards. Benatia and Chiellini, meanwhile, generated a numerical advantage over Kane.

For one, this forced Barzagli into one-on-one duels with Son, who took on wide positions in the final attacking line. Barzagli had a clear-cut disadvantage in terms of speed, which led to a number of dangerous opportunities. Douglas Costa was only able to help in deeper pressing situations. Otherwise he was too far away from the 36-year-old because of his own covering duties.

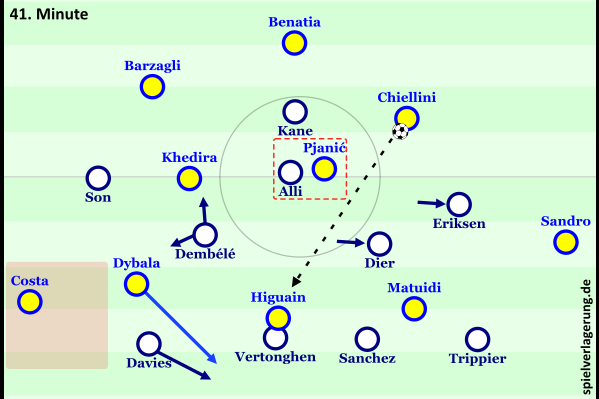

Secondly, Juventus’ No. 6 space was relatively open and Spurs were able to create a decent presence for rebound from clearances or layoffs from Kane. Pjanic initially tended to follow Alli, but ultimately kept to his position more cleary and kept an eye on him. The assignment of Eriksen failed to become very clear. Chiellini was able to move towards him out of the back line, but that was not possible after passes to Kane, since he had to cover behind Benatia in those instances, with the English striker orientating himself towards Benatia more often. Kane at times evaded far to the right wing in the space behind Alex Sandro as well, though. In that case, Chiellini had to take him.

Alex Sandro could not focus purely on guarding Eriksen, because Trippier was without a direct opponent and saw either the Brazilian from a deeper position or Matuidi from higher up the pitch running at him, depending on the situation. The former Paris Saint-Germain man was thus prevented from helping to cover the No. 6 space.

Leaving Trippier open was probably no coincidence, however. He could only be reached with high passes which generally seemed to hang in the air a good while. This allows the player running at him enough time to put pressure on him and cut off other options. Simply playing towards Trippier would thus not have been enough to get the better of Juventus. In fact, they might have given the Italian champions good opportunities to win balls in promising situations.

Only Eriksen’s dropping back became, here and in other areas of the match, the decisive wrinkle against the man-oriented playing style. He caused a chain reaction: Matuidi pushed towards the (naturally) more deeply positioned Trippier, which meant Pjanic had to follow Eriksen. Dier pushed a little higher in the same moment. Khedira was still constrained due to his previous orientation towards Dembele and could only react too late.

Sanchez was able to pass between the lines. Though a direct shifting of play towards the ball-far side was prevented, Tottenham were able to use their dynamism in the open spaces. Eriksen immediately pushed forward, Kane found him in the half-space. In the meantime, Tripper moved up on the wing and reached the ball after a mishit from Alli.

The full-back’s cross found Son at the far post, with Barzagli still occupied in the centre of defence. The South Korean finished unconventionally, putting his team in front. Not only in this situation, the hosts impressed with their quick and strong (in terms of numbers) occupation of the penalty box, while still covering for rebounds, which they often use for attempts from distance — Eriksen, for example, is a specialist for those.

Tottenham also used man-orientations in their own high pressing. However, in Mauricio Pochettino’s system they don’t serve the purpose of preventing every pass completely, but to have an opponent close enough to attack him immediately and to aggressively disturb him during the first touch. To that end, team-mates push forward as well to constrict the space further, instead of freezing in their own man-orientations.

When Juventus built up play in a back three, Son immediately ran at Barzagli, while Kan covered passing lanes towards the other side of the pitch. With the covering of the other played this resulted in a 4-diamond-2 alignment as a reaction to the 3-diamond-3 shape the Old Lady showed in the build-up phase. When Barzagli moved a little higher, however, Son remained deeper himself, to run at him when the defender received the ball. The formation in those instances matched a 4-2-3-1.

A particularly strong moment of access developed when Barzagli played towards Douglas Costa from a deeper position. The distance of that kind of pass was enormous and Davies and his team-mates had a lot of time to position themselves accordingly. Even the Brazilian’s dribbling qualities, still well-known from his days at Bayern Munich, were stretched to their limits in situations where he was clearly outnumbered. Alternatively, Juventus opted for long balls early, which were not overly effective.

Phase 2: They way to 4-2-3-1 is the way to victory

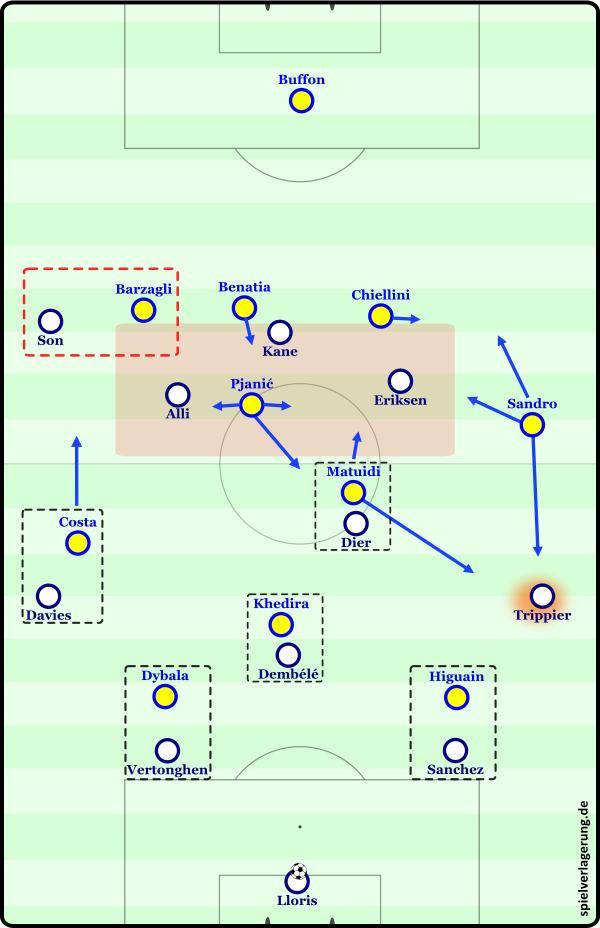

Littly by little, however, the downside to the pressing of the hosts became obvious: You have to run at your respective opponent with a lot of intensity, or he gets too much time to make decisions. It’s hardly possible to keep that approach going consistently for 90 minutes. Tottenham falls back deeper and, further, becomes more passive in trying to find access.

This became even more of a weakness since Juventus found an approach or two, even when Tottenham were more dominant, which they developed further throughout the game thanks in part to smaller tactical adjustments. For one thing, the overloads on the right wing deserve mention. Both Khedira and Dybala moved towards the sideline even in the first half, with Costa moving inside diagonally. Davies followed him with that or refrained from immediately attacking on the wing. This way Juventus frequently gained open players. Spurs failed to pressure and contain intensively.

At the same time, Alex Sandro and Matuidi workes as a pair on the left, even though the latter dropped away again and again. Dybala also managed to support them here on occasion. This was more about finding a direct passing avenue towards Higuain, though, and about isolating Douglas Costa on the right wing with the corresponding movements.

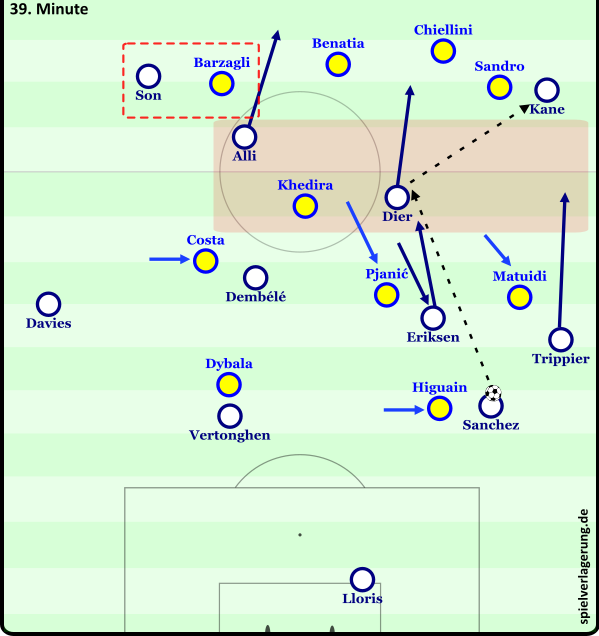

With the game progressing they found larger spaces for this, since Tottenham’s four-man midfield appearing increasingly out of synch and Alli taking care of Pjanic. At the same time Matuidi pushed forward more deeply, while Khedira remained deeper on the right in the build-up phase particularly in the second half. He only attacked the penalty box for crosses later during offensive moves.

In their deeper pressing Juventus generally played, with a few exceptions, with a deeper Douglas Costa in a 4-4-1-1/4-4-2 and were thus stucturally not far away from a 4-2-3-1. This trend was amplified in regards to their possession play through their changes. In terms of personnel, Kwadwo Asamoah came on for Matuidi in the 60th minute. Alex Sandro moved into midfield. The No. 8 role in possession definitely turned into that of a inside-winger, through which the building of pairs from the first half was now transferred into higher zones on the field.

Only a minute later, Lichtsteiner replaced Benatia. Barzaglia became a centre-back, Lichtsteiner played as a full-back, wether Juventus was in possession or not. This way, Juventus developed a clear structure, in which Dybala played the most important part. As a No. 10 he moved from one side to the other to create overloads. Higuain tied up the centre-backs, while Tottenham’s full-backs had direct opponents in their perimeter on both wings.

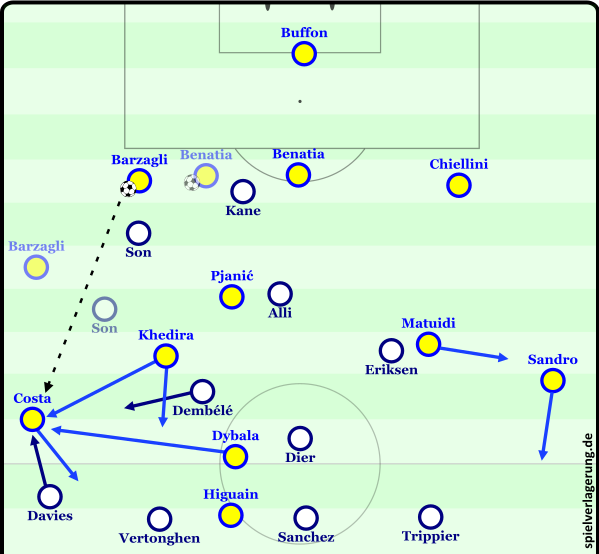

The goal to make it 1-1 came about after an overload on the right wing. The goal to mae it 2-1 came about after an overload on the left side was resolved and the ball went back to Chiellini. He was able to pass toward Higuain without disturbance, who then found Dybala. The Argentine was “left over” from the overload and sprinted behind the defensive line. Davies played him onside on the side away from the ball by staying with Douglas Costa. That was not the case for the first time on the evening, by the way–Tottenham’s other players had simply been able to find better access in a similar situation during the first half, while Juventus’ runs did not fit together perfectly either.

Movement in their 4-2-3-1 shape, when Juventus scored two goals in four minutes; Dybala was everywhere

Final phase and final remarks

After going behind the hosts did not react rashly whatsoever, as one may have expected to happen. Juventus on the other hand fell back towards their own box after a few minutes of higher pressing in a now clear-cut 4-4-1-1, which in turn was entirely to be expected. Later, Stefano Sturaro came on as a fill-in to create a 4-1-4-1/4-5-1.

Spurs found a certain stability in the first line and circulated the ball through Dier’s falling away. Eriksen moved deeper to drive his team forward. After Dier was taken off, the Dane and Dembele filled the double pivot. Lamela entered the game. Now at the latest Tottenham managed to overload the centre and left only one player per side to provide width.

They did use this alignment for crosses, especially after the late arrival of Fernando Llorente for Alli. But those were not swung into the box blindly, rather coming in the context of combinations and dribbles, which, for example, opened spaces at the far post or led to counter-pressing moments, which in turn created open spaces in or around the box. But it was not enough for a late goal.

The perceived dominance of the English side thus remained a false belief both in terms of the actual result and of the expected goals (1.8 to 1.5 in this match, 3.4 to 2.5 +2 penalties over both legs), even though a progression to the next round would indeed have been deserved. At times, the pacey playing style, the explosive occupation of the box and the number of shots from middle distances make some attacks look more promising than they actually are. Juventus, on the other hand, created fewer conclusions, but theirs were of higher quality.

In a slight exaggeration one could say looking at the game in its entirety, that the tactician Massimiliano Allegri beat the strategian Pochettino impressively. The Argentine’s plan A, the typical approach to the match, worked close to perfection roughly until half time, until his counterpart, whose specific plans at first did not work too well, reacted cleverly to the signs of attrition in his opponents.

Should he just have played in a 4-2-3-1 from the start? Picturing that kind of alignment against the early showing of Tottenham, one can only say no. They would have been able to defend the relatively clear distribution of roles almost ideally despite the free role of Dybala.

That is the art of in-game coaching: To find the right moment for a tactical knack. What may seem senseless at first can become match-deciding in a different context. Primarily, that has nothing to do with sensitivities or individual preferences, but with the goings-on on the field. This is were one probably finds the biggest difference between amateur and professional. Massimiliano Allegri, at any rate, showed against a well set-up opponent that he is one of the most savvy coaches of his time on the grand European stage.

This article was written by ES (@EduardVSchmidt) and translated by Lars Pollmann (@LarsPollmann).

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen