Aspect Analysis: Manchester City dismantle Cardiff’s man-marking

Touted going into the fixture as unusual opponents, Guardiola’s Manchester City were drawn away to promotion candidates Cardiff City for the 4th Round of the FA Cup. The Bluebirds, managed by Neil Warnock, tried to nullify the Citizen’s threats by utilizing a stricter form of man-marking in defense. Posing a different test than what they usually face in the league and Europe, this piece explores how Manchester City overcame Cardiff’s marking.

Moving the Opponent

As we’ve previously discussed, when faced with man-marking, being able to create space through either individual or group mechanisms is a crucial component to successfully breaking down the opposition. Through intelligent actions, players can manipulate the opponent to create advantageous situations for themselves and their teammates. This can either by done for the player on the ball, or via movement off the ball to create playing situations in more dangerous areas of the pitch.

Dismarking is both an individual and a team phenomena, so an individual dismarking action can have implications that go beyond the scope of one player.

Build Up

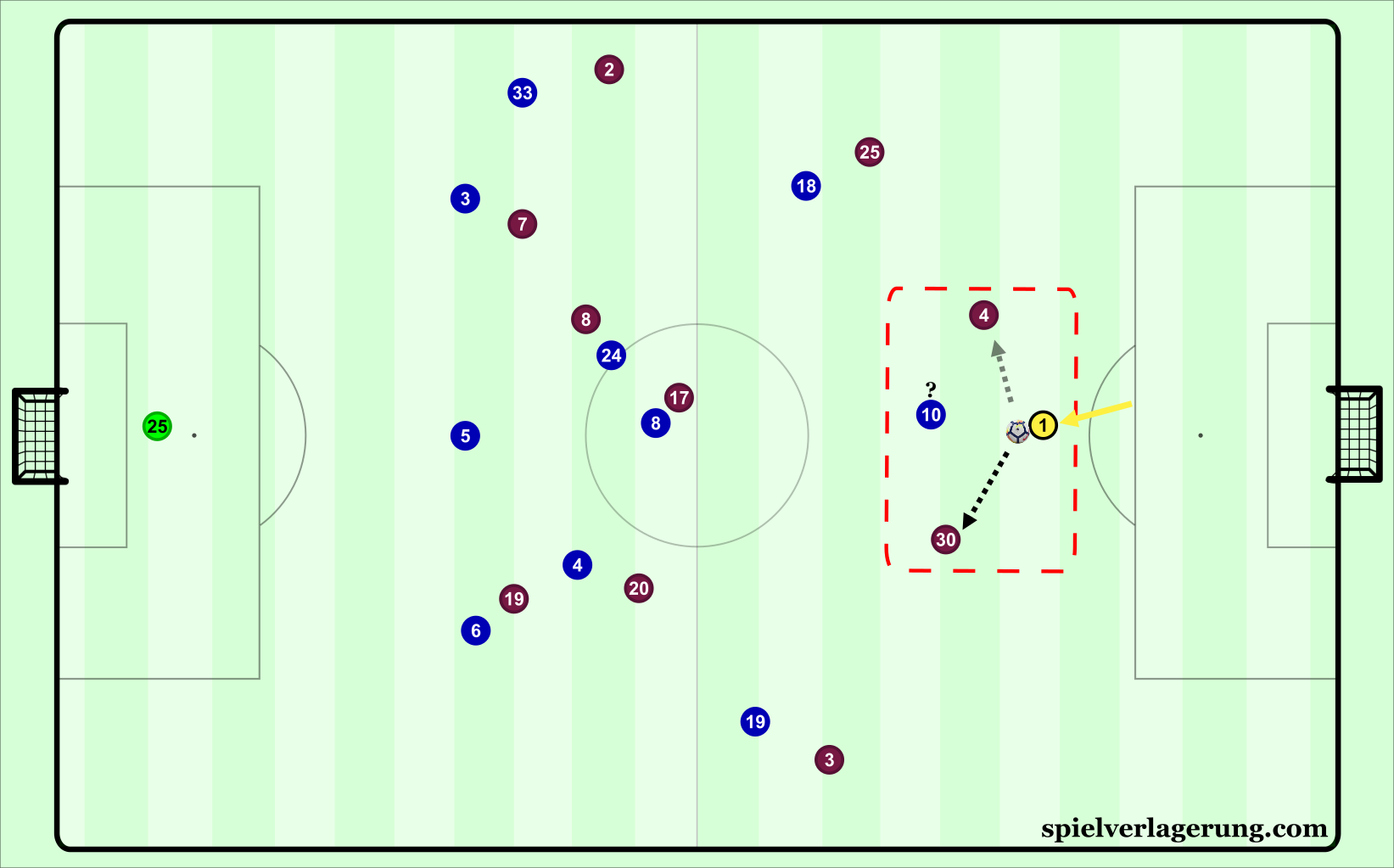

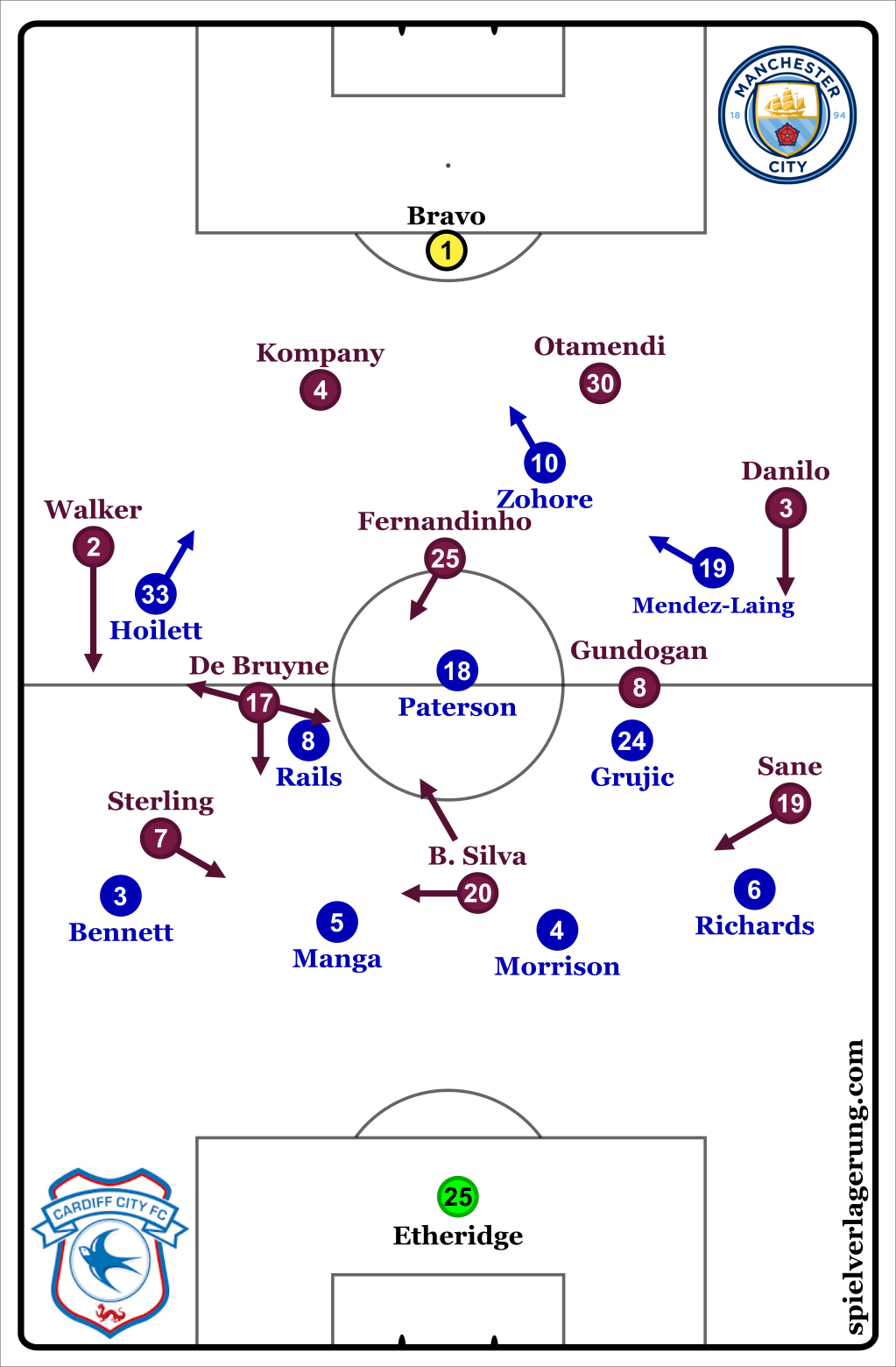

Manchester City’s build up against Cardiff City was strategically focused on taking advantage of the free players available in their shape. Since Cardiff decided to have the wingers mark Walker and Danilo, Zohore had to choose between covering Kompany or Otamendi. Warnock chose to match Guardiola numerically in the midfield, leaving Manga as the extra defender without a player to mark (Morrison predominately marked Bernardo Silva).

From City’s perspective, this made progressing up the field quite simple. The main target of their circulation would be to find the free man, and if the free man has the ball and gets pressured by a Cardiff player, they target the next passes to eventually find the player that was abandoned. Considering City’s players are skilled in tight spaces and handling pressure, this was an easy task for them. Once the free player was found, they could move up the pitch through dribbling until pressure was applied. Then the whole cycle would continue once again up until the final third.

There were three main mechanisms that were commonly seen throughout the match for how City progressed up the pitch for their build up. Due to Vincent Kompany being the free player, they are predominately centered around him and the decisions (or lack thereof) that Cardiff made when he was in possession.

In the first mechanism, because of Cardiff being reluctant to leave their markers, Kompany could dribble up without having any pressure applied to him. This was made possible by City’s midfielders deliberately moving away from the right halfspace, dragging their man with them concurrently. This would leave this area open for Kompany to dribble into. Thanks to the lack of pressure, the Belgian captain could at moments either stand with the ball and do nothing, or move up with not a single Cardiff player changing their orientation.

Occasionally, some players would adopt intermediate positions between Kompany and the marked player, but the City captain was hardly exposed to real pressure. By this point, City would be above halfway and be on their way to establishing their presence in Cardiff’s half. When moving away from the right halfspace, the midfielders would also move into higher lines, anticipating future line breaking passes from the defense that would come later in the attack.

After receiving the pass from Fernandinho, Kompany can dribble into the right halfspace with little pressure due to Cardiff players preferring to stay close to their man.

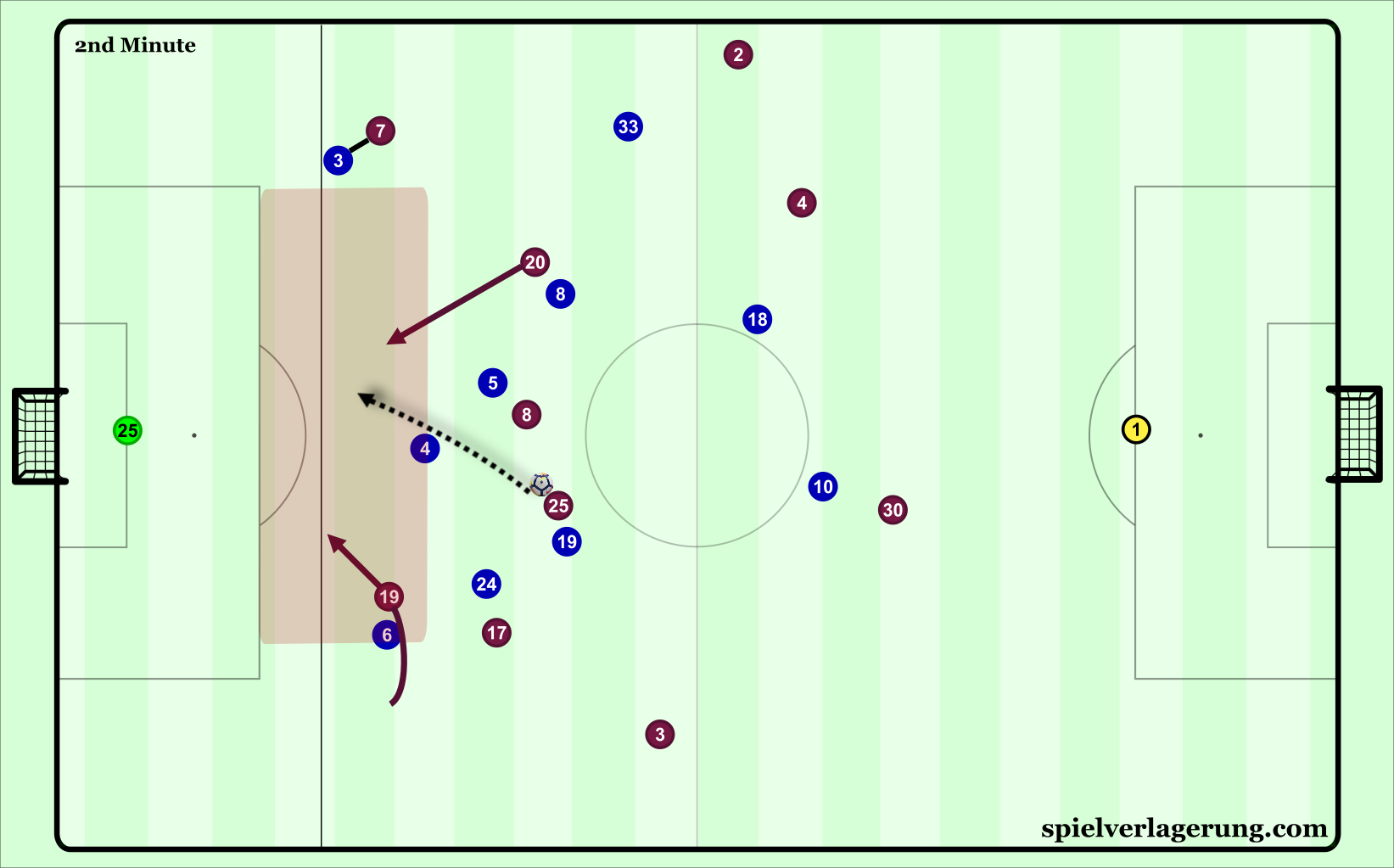

Once Cardiff adjusted slightly to Kompany’s dribbles, he chose to keep the ball rather than risk losing it in an early stage of their attack. Which brings us to the second mechanism in which the visitors took advantage of their numerical advantage in build up. After a tipping point where Cardiff were tired of chasing the ball, eventually someone would leave their man to press the ball. Once this happened, City looked for to target the subsequent passes to the free man. Since the free player was usually covered in the immediate moments, an intermediary player would have to receive the second pass. This player would then find the free player, the third man in this case.

This most often happened with Paterson, the closest player to pressure the second center back with Zohore. When moving to approach, he in turn had to leave Fernandinho. Kompany or Otamendi would then play to a nearby midfielder or out wide to advance the ball. During this time, the Brazilian would move forward and prepare to receive the next pass, oftentimes moving in the blindside of Paterson. Once Fernandinho received the passes, which were typically well-timed with his movements, Paterson was often visually frustrated and annoyed with his teammates. These third man combinations were close to effortless for the Premier League leaders, but nevertheless they were instrumental in carving apart Cardiff’s man-marking throughout the evening.

After Paterson leaves Fernandinho to pressure Kompany, Kompany passes to Walker. Sensing Fernandinho is free because of this, Walker plays to a wide open Fernandinho, with the pass cleverly dummied by De Bruyne. Fernandinho goes on to easily dribble forward afterwards as a result of this third man combination, much to the anger of Paterson.

Lastly, when recirculating possession in the backline, Claudio Bravo would move to support Kompany and Otamendi. The distance he occupied was no further than 35 meters from goal, a spot that demonstrates some level of risk. He provided a secure pivot for the ball to be switched for one side to the other, making Zohore helpless defensively at the same time. The Danish forward was faced with a dilemma when Bravo put himself in the play. If he pressured Bravo, the Chilean easily passes to one of the centre backs, who then dribble up the pitch and progress without any opposition. If he does not pressure, he then chooses to cover a centre back, leaving the other one open.

Due to their spacing and his fitness limitations, he could not cover one and go and chase the other. This made Zohore doomed when Bravo supported the play. When Bravo was used to facilitate the first stage of possession, it guaranteed progression up the pitch because of the numerical advantage provided over Zohore and Cardiff.

When Bravo moves up into the defensive line for possession, he can pass to either centre back free of pressure. Because of the numbers, Zohore is largely unsure of what to do, and does not pose any significant problem to the Citizens.

Chance Creation

Moving into the final third. Chance creation against Cardiff as a result of their man-marking aimed to move their defenders into spaces of the pitch not normally occupied. As Guardiola said in his post match press conference about Cardiff, “If you go to the right, they follow you to the right. If you go left, they follow you to the left. If you go here in the locker room, they follow you in the locker room”.

The most significant way that Cardiff was moved around defensively was through the positioning of the front three, particularly Bernardo Silva. The Portuguese international started the match as a false 9, checking deep to get the ball under the pretense that Manga and Morrison would not follow him, earning a 4v3 in midfield. However, Manga frequently followed Bernardo, to the point that if Bernardo was 10 yards away from the ball and decided to move to his starting spot, Manga would mimic his steps when it appeared comical to do so.

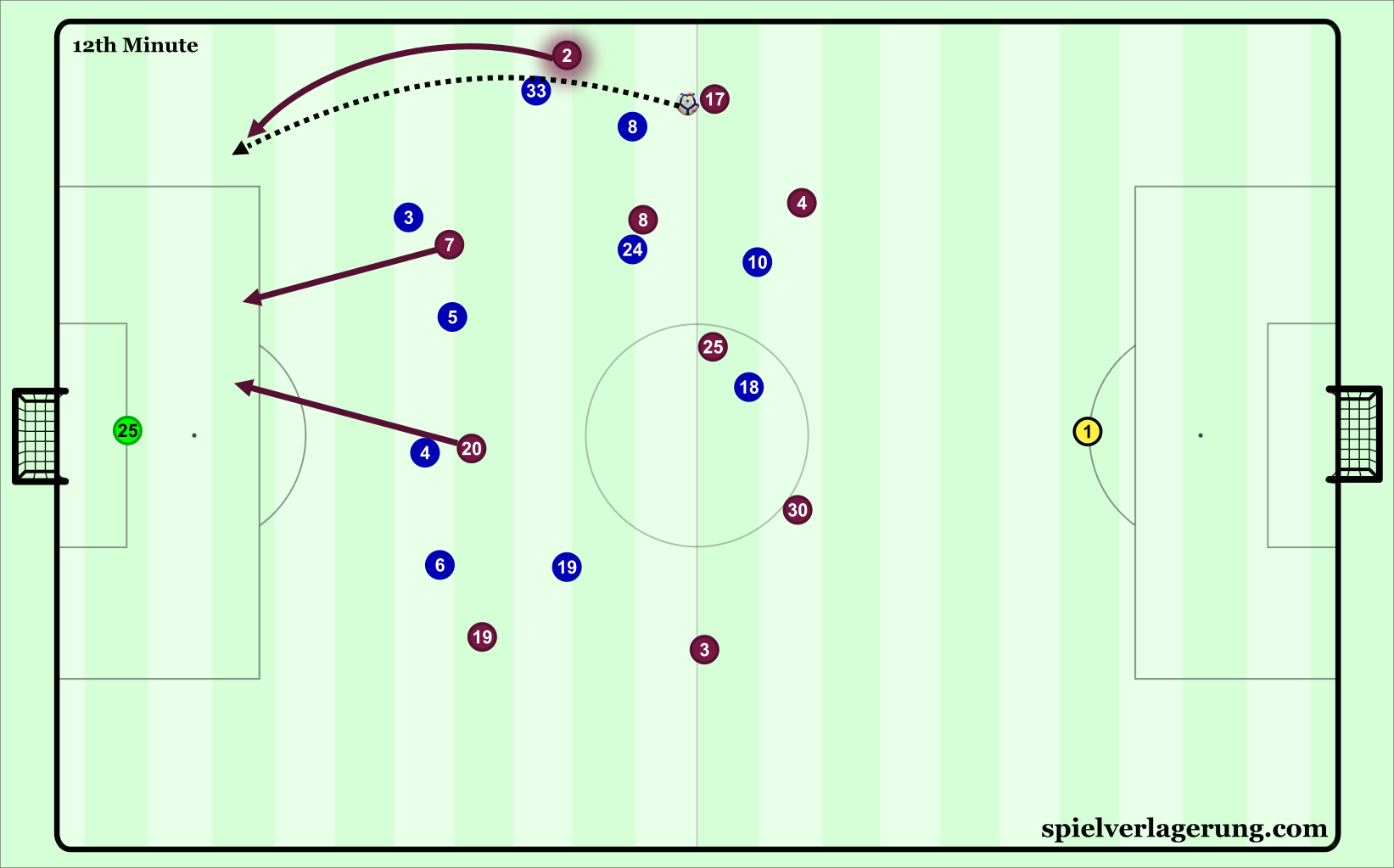

Morrison tried to move up the defensive line when Silva checked to the ball, but this hardly worked because of the rigidity in the fullbacks’ marking of Sterling and Sane. Despite Morrison and Manga’s efforts to step up, both Bennett and Richards failed to recognize this, leading to large central avenues for diagonal runs to be made into. Sane and Sterling each targeted this free space repeatedly with their movements, and Bernardo Silva would also make double runs to capitalize off this defensive error.

However, the subsequent through passes played were either blocked by Cardiff, or the runs weren’t seen by the player with possession, leading to no pass at all. In some instances, if the pass was played aerially rather than on the ground, then City would’ve managed to get in behind more often than they did, provided that the passes were the correct weight.

Because of Cardiff’s rigid marking, Bennett has set a deep offside line for Sane and Silva to run into. If Fernandinho opted to chip this pass to Silva instead of play it on the ground, Manchester City would’ve had an excellent goal opportunity.

Another way that City moved around Cardiff in defense was through horizontal movements out of their base positions. By having moving players from their “traditional” side, Cardiff’s defenders were thrown for a loop when they were dragged in areas not typically occupied in their positions, or they would temporarily cover them.

The Cardiff midfield line dealt with this slightly better than the defense. Rails and Grujic were seen switching their marks at periods of the game with De Bruyne and Gundogan respectively. The centre backs often failed to adequately pick up Sterling and Sane when they move toward the interior due to their fixation with Bernardo Silva. This led to several decent chances for Sterling and Sane, one of which the former converted with just under ten minutes remaining in the half.

Wide Interactions

Another area of note in terms of how the Citizens used their individual superiorities in wide areas to capitalize on Cardiff’s man to man play. Because of the main reference point for Cardiff being an individual player, this divides the pitch into a series of individual duels from their perspective. Luckily for the visiting club, the ability, game insight, and speed that they possess in wide areas makes it likely that they win a large percentage of these individual battles.

The same positional habits from the 8’s were seen in terms of their movement into wide areas, while pushing the full backs up in response. Since Rails was reluctant to pressure De Bruyne out near the wing, he had ample time to pick out passes to threats than ran in behind. The most common superiority he targeted on the wings was Kyle Walker, whose retreated positioning gave him a head start on his runs. Hoilett would be backpedaling and retreating in response to Walker’s runs, which would either lead to separation and eventually trailing behind Walker if he got the ball, or to Hoilett moving into the back line and acting as an auxiliary fullback.

An example of De Bruyne finding Walker on the wing. Due to Bennett’s narrow positioning, Walker’s run is more effective. Sterling and Silva then begin their runs, anticipating a cutback cross from Walker.

On the left side, it was less about taking advantage of individual qualities and more about intricate combinations and timing. The left side aimed to have more third man combinations in the mold of Fernandinho earlier, with the runs originating from deeper positions than Walker’s, while also receiving more support from Gundogan and Bernardo Silva in the opening phases of the match. Through superior speed of play and timing was how Manchester City’s left flank broke down Cardiff, most notably seen with the passage of play prior to De Bruyne’s free kick goal.

Conclusion

This match demonstrated the versatility of possibilities that Pep Guardiola’s team can deploy when it came to defeating man-marking opponents. Most of the second half from Manchester City’s perspective was composed of defensive possession, aiming to tire Cardiff. It is not out of the realm of possibility that this was done to avoid injuries, as Leroy Sane had to be replaced at halftime due to a reckless tackle from Joe Bennett that was worthy of a red card. Some desirable goalscoring chances were created, but no more converted after City’s impressive first half.

The Welsh club were quintessentially English in their match approach, playing quite direct in their attack and treating every set piece as a golden opportunity. Man-marking might have been a different problem than what City normally encounter, but it was not more difficult or more complex. English football might have different on field problems than the rest of the world, but that doesn’t necessarily make it better. Fun fact: the last English manager to have his team win the first division was Howard Wilkinson in 1992. Here’s to a quarter century of English managerial and tactical innovation.

(Author’s Note: More non-Man City work will come in the future from me)

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

Ollie January 31, 2018 um 9:12 am

Great analysis as ever. Any possibility of an analysis of the Man City v Liverpool game?

AR February 1, 2018 um 3:29 am

Thank you for the comment! For the Liverpool match, I recommend reading ES’s analysis on the .de website. Google translate works well for it.