How Borussia Dortmund beat a brilliant Juventus side in the 1997 Champions League final

The 1997 Champions League Final pitted Juventus against Borussia Dortmund. The Bianconeri were under the stewardship of the legendary Marcello Lippi. This was in some ways a game of typical of nineties football however there were some impressive modern features from the iconic Italian side. In a guest analysis James Curzon delves into the game’s details.

Juventus’ defending

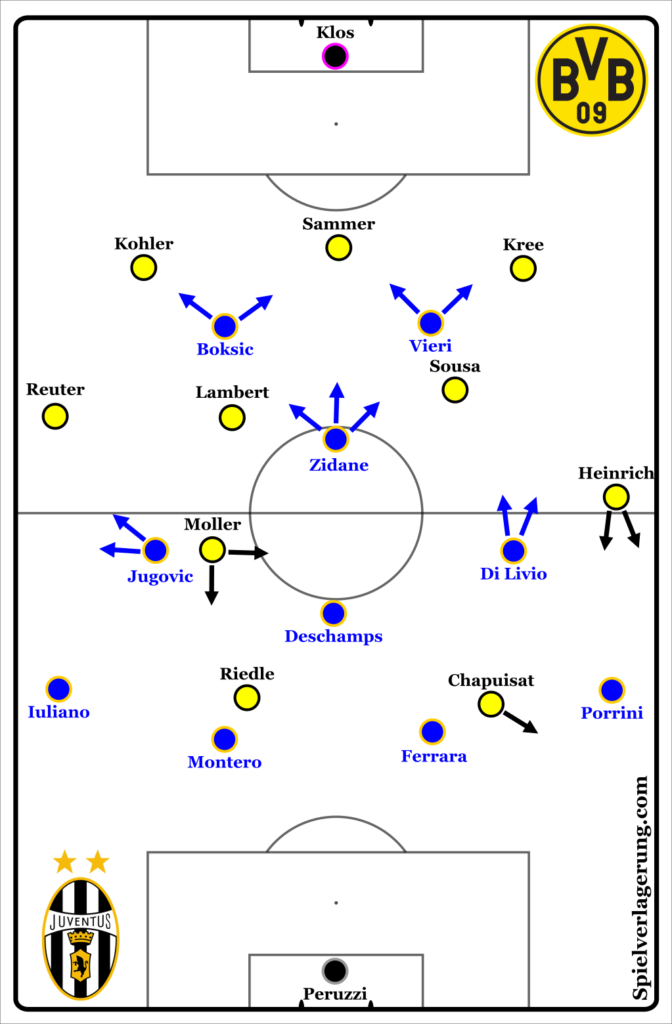

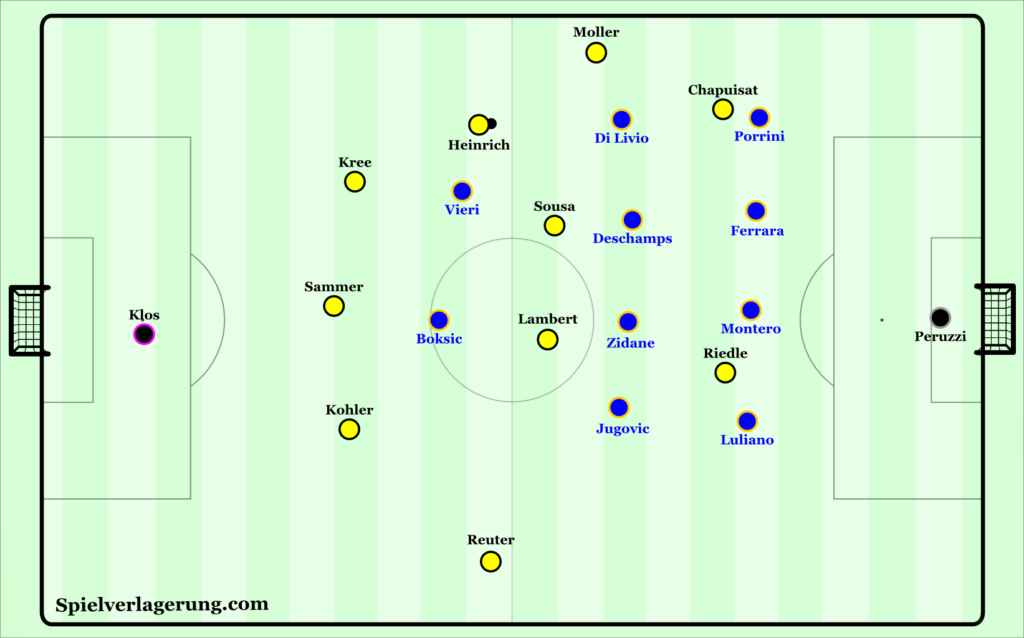

The Italians operated in a 4-3-1-2 with a strong position-oriented defensive game demonstrating excellent proficiency in controlling the centre and trapping the opposition by the touchline. Borussia Dortmund lined up in a 3-4-1-2 which, by comparison was lacking in compactness.

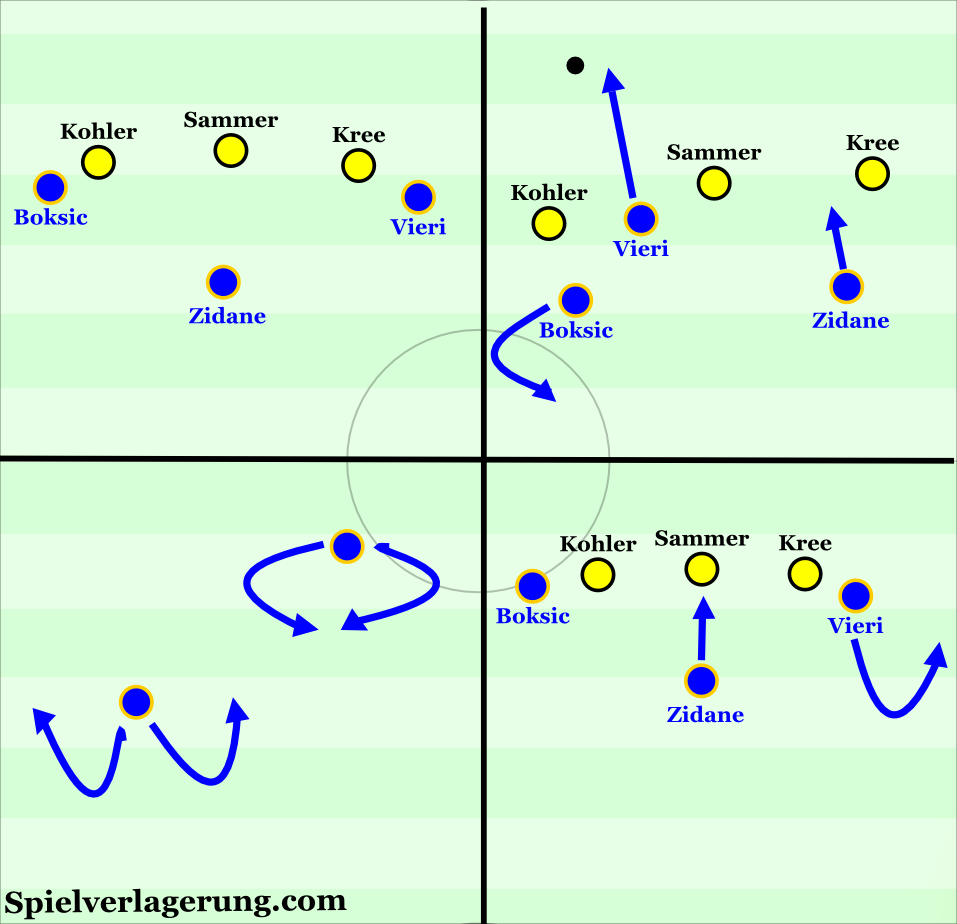

Dortmund played backwards from kick-off and the Juventus forwards Boksic and Vieri immediately began pressing, using curved runs to generate a cover shadow, isolating Kree, the outside centre back and forcing him into a blind clearance which resulted in a Dortmund throw.

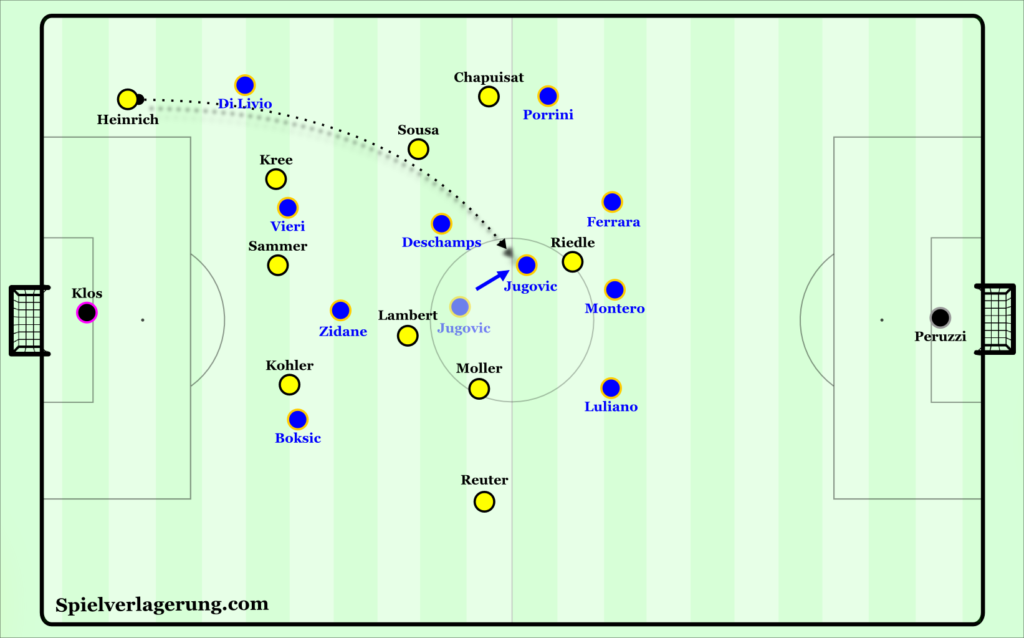

It was from this throw, itself originating from the opening stages of play that Juventus were first able to execute their well-coordinated defensive scheme. Vieri anticipated a backward throw and oriented himself closely by Sammer with the intent to intercept any throw back to Klos. Kree threw the ball over Boksic and Zidane, and through a Juventus challenge it landed at the feet of Heinrich, the BVB left-wingback. From here the Juventus diamond midfield acted as a typical 4-chain would in a 4-4-2.

The crucial difference was Zidane recovering backwards in order to cut out horizontal passes in front of the Juve midfield, and deny BVB access to the 6-space. Boksic adjusted to put Kree in his cover shadow,along with the presence of Vieri deterring any passes to Sammer, this ensured BVB would not be able to play backwards out of the pressure. Di Livio protected the half-space and edged out in order to press Heinrich who then played forward into Chapuisat.

Through well-coordinated control of space, Juventus encouraged the pass into Chapuisat who received the ball with a body-shape that wasn’t conducive to playing forward. The supporting positions of Chapuisat’s team-mates were sub-optimal and in any case the Juventus midfield cover isolated him effectively. Upon receiving, Di Livio and Deschamps began to close in from the front and side whilst Porrini prevented Chapuisat from turning. With intelligent use of their cover shadow, Di Livio and Deschamps prevented any passes from escaping the area of pressure.

This was supplemented by Zidane adjusting his position to continue to screen any horizontal passes in front of the narrow midfield. Though it must be noted Dortmund’s possession structure was quite poor, (a theme throughout the match) a well-executed, modern and efficient defensive scheme enabled Juventus to deny BVB from progressing and eventually resulted in a counter-attack for La VecchiaSignora.

The presence of Jugovic on the opposite side of the diamond made for slightly different dynamics on the left-touchline. Angelo Di Livio was an extremely dynamic and mobile player who was frequently deployed as a wing-back or a full-back, and his position on the right-hand side meant that Juventus were more successful in trapping opponents there or winning back the ball. This was partly due to his characteristics as an energetic and attentive defensive player (making him better suited to defending and regaining possession in tight spaces than the comparatively slow Jugovic).

The variation in positioning between Dortmund’s wingbacks should also be taken into account. Heinrich was the more progressive of the two throughout the match (winning one of the corners that led to a Dortmund goal) and often received the ball within the Juventus block, between Porrini and Di Livio or slightly deeper. On the right side, Reuter often positioned himself much deeper and therefore received possession in areas Juventus couldn’t immediately pressure. The combination of Reuter’s deeper positioning and Jugovic’s comparative lack of mobility meant the Yugoslav was less able to regain possession. However, through intelligent positioning and well-timed group defensive dynamics Juventus were able to compensate for this.

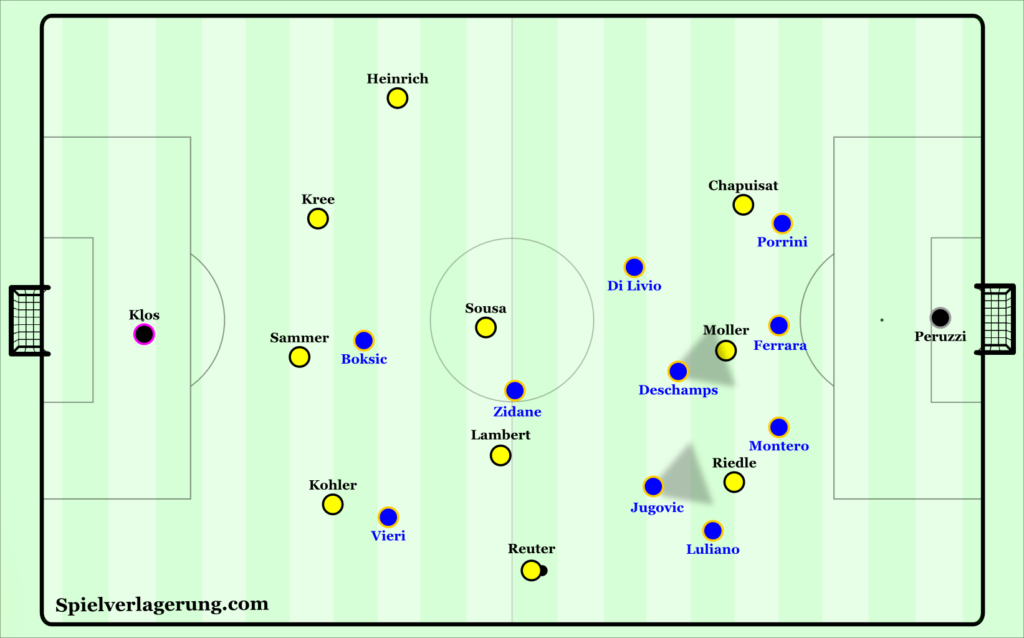

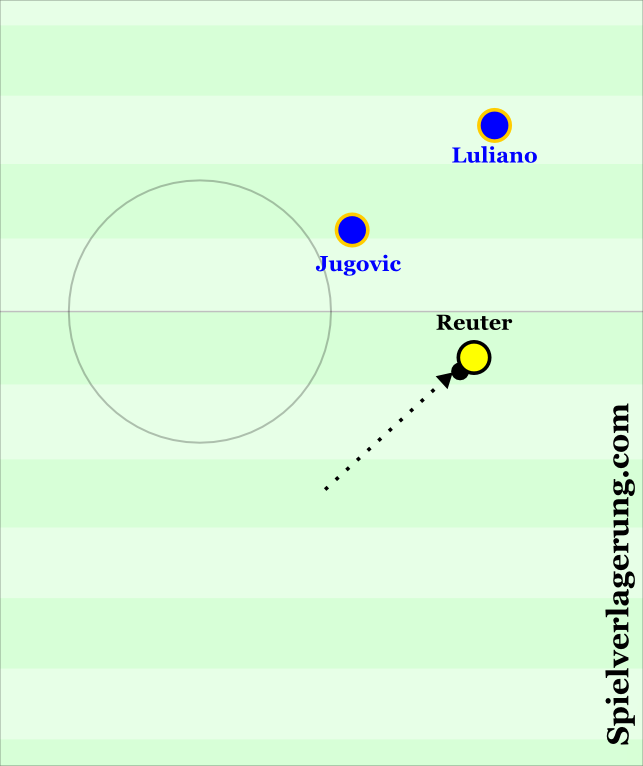

Juventus’ diamond dominated the centre of the pitch, so Dortmund were often forced to the flanks to progress towards goal. When Reuter received the ball in front of Jugovic, the Yugoslavian could press as a left-sided midfielder, or guard the half-space and delay forward passes, to then creep forward and attempt to pressthe ball. Iuliano’s positioning was crucial as he edged up to support Jugovic, this prevented easy ground passes beyond the midfield. This also denied Riedle the opportunity to secure the ball by moving across the defensive line to pin the left-back.

Although Deschamps and Jugovic used their cover shadow to take Möller out of the game, in theory a low ground pass into the feet of Riedle would have allowed BVB to bypass this screen, and use the support of Möller and the movement of Reuter to combine into a goalscoring position. However, with this being a Lippi coached Juventus side (limiting forward passing options and squeezing the 6 space with Zidane and denying backpasses through Vieri) against a 90’s era Dortmund the ball was clipped speculatively forward and Juve were able to clear with ease.

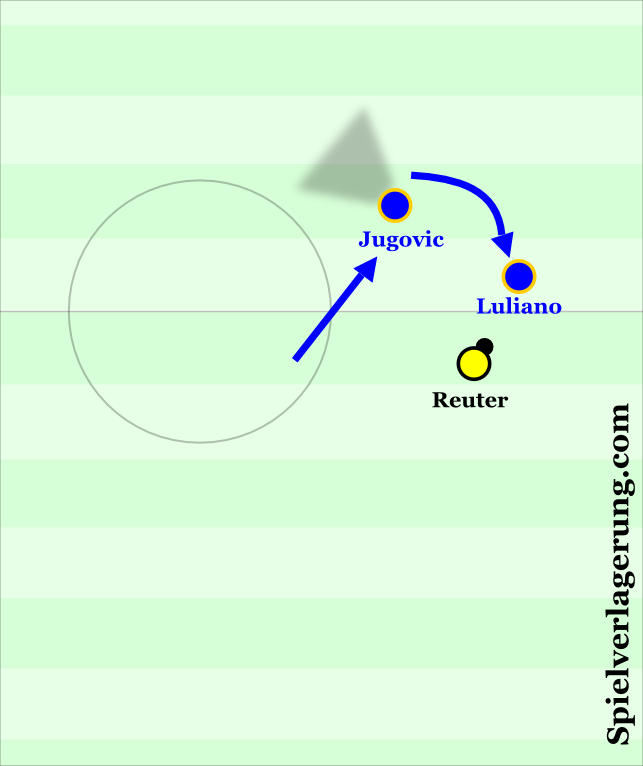

The other scenario which occasionally arose was Reuter receiving beyond the line of Jugovic’s body, in this case Iuliano would pressurise Reuter and prevent him from playing forward. Whilst the Italian delayed Reuter, Jugovic would recover into a covering position behind Iuliano. This created a 4-chain in front of the defense with the left-back becoming a left-midfielder, his cover shadow would protect the space he vacated.

Juventus exhibited excellent protection of important spaces during their defensive organisation and shifts, they frequently regained the ball. Dortmund could hardly progress and create chances from open play during the first half. They managed to turn the traditional weakness of a narrow diamond midfield into a strength with well-timed pressing movements on the wings and compactness through the centre of the pitch. In addition, the forwards recovered and marked defenders to deny horizontal and backward passes, albeit against a Dortmund side with a poorly developed possession game.

Zidane’s role

The role of the French genius was pivotal in this side and at Juventus he was a far more rounded team player than often remembered. By recovering backwards he assisted in trapping BVB on the touchline, denying passes into the 6-space and freeing Boksic and Vieri from having to backward press. This allowed them to conserve energy for attacks and let them stay in an advanced position to deny backward passes and prepare for counter-attacks. He showed intelligent movements and positional adjustments to strengthen the Juventus shape and restrict Dortmund’s ball circulation.

Although Dortmund rarely included their defenders in their possession game and seldom built attacks from deep, Juve demonstrated that they were capable of controlling the Dortmund back 3.

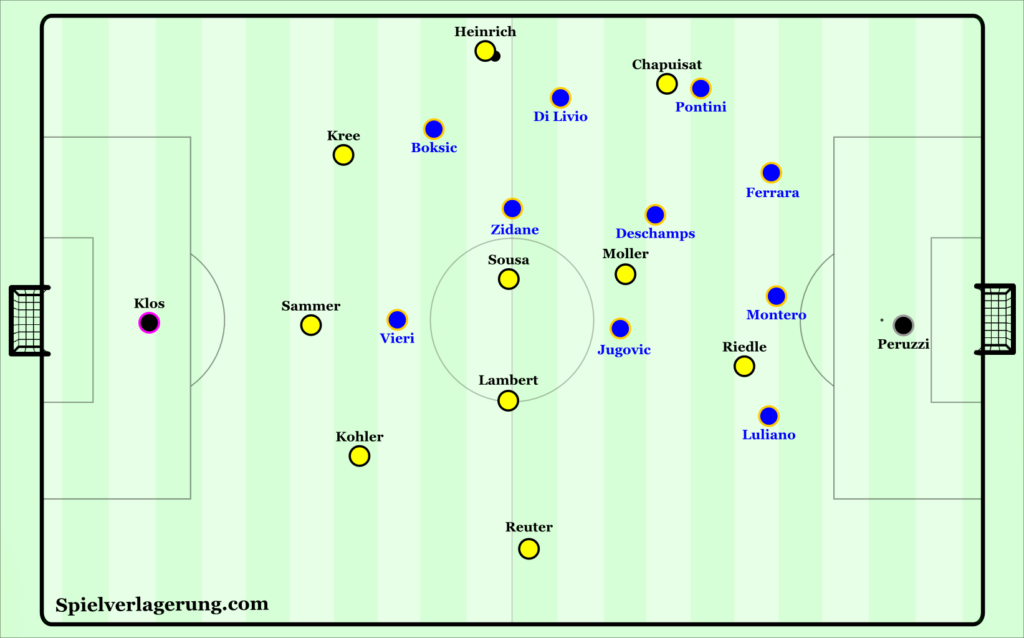

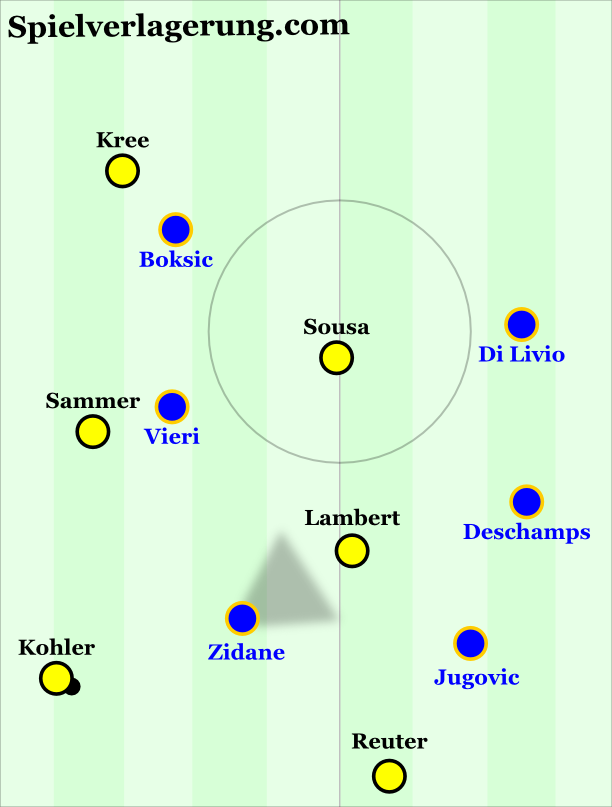

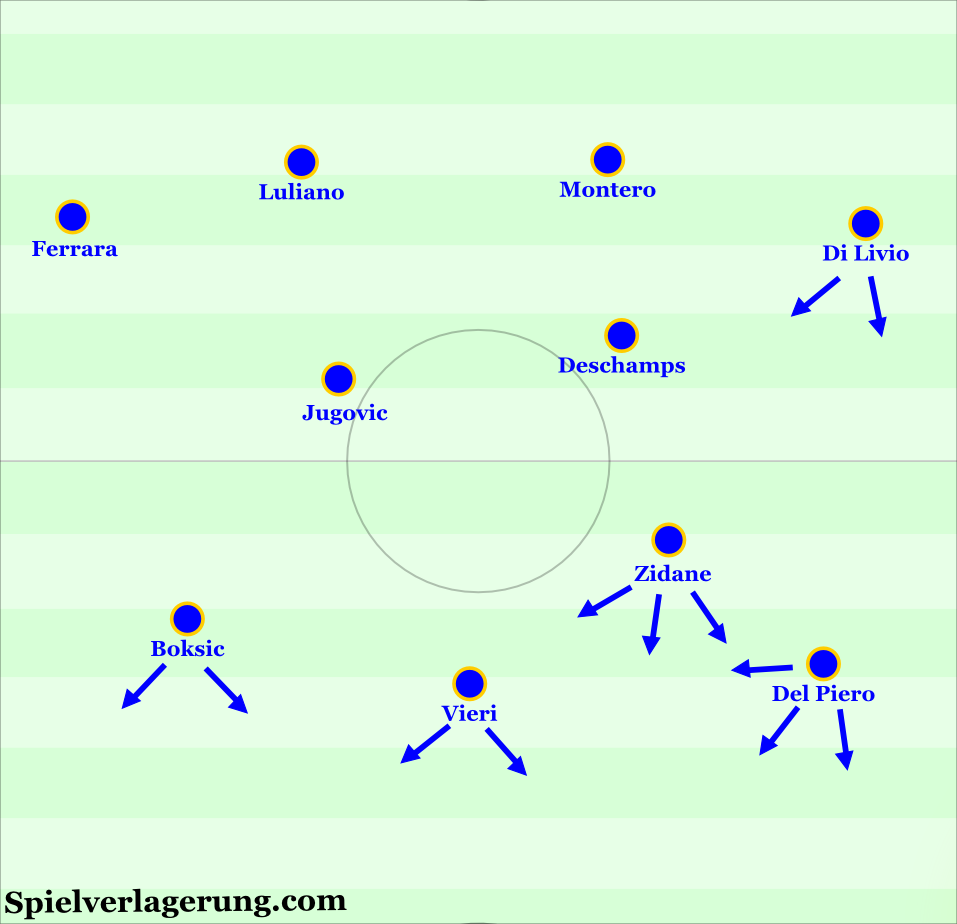

With Vieri and Boksic man oriented to Sammer and Kree, Köhler was the free man in bringing the ball out from the back. Zidane nudged up from his position as the 10 in order to force Köhler away from the middle of the pitch and into Reuter on the left flank. Zidane’s movement placed Lambert and Sousa in his cover shadow and the presence of the midfield 3-chain behind him ensured all forward passes were covered.

On rare occasions Zidane recovered into central midfield forming a regular 4-chain alongside his countryman Deschamps. This usually occurred when the ball progressed down the left-flank and was unlikely to come backwards or across the 6 space. He would then drop to the right of his compatriot as Deschamps was drawn into a position to cover Jugovic. This was likely due to Dortmund’s strength in aerial situations and Lippi had probably planned to have the presence of an extra man in or around the box.

At times when play became stretched or Klos kicked long from his hands, Zidane fell into the 4-chain to allow Juventus to gain stability as in the scene here. Vieri and Boksic began to backward press to delay Dortmund’s attack, and the diamond was recovered at an appropriate point. Even with the 6 space unguarded, Dortmund’s structure in possession didn’t pose much of a threat.

Juventus’ avenues of attack

Ironically it could be argued that Juve’s attacks lost them the game. With a few exceptions they attempted to play forward as quickly and directly as possible, aiming to use the aggression and directness of their two forwards to overwhelm Dortmund. If they managed to develop play into the Dortmund half, they tried to play direct crosses and find isolations in the BVB penalty area.Juventus aimed to progress the ball forwards as quickly as possible and used two different types of movement to achieve this.

The base position of Vieri and Boksic was on opposite sides of the back three, this was an attempt to isolate the covering defender in the 3-chain in order to create 1v1’s and play into the spaces left open by their advancing wing-backs. From this base position, the forwards had two types of movement:

1) A curved movement across the defender, away from goal and toward the ball

2) A curved movement across the defender, away from the ball and towards goal.

One forward (the trigger) provided the initial movement, and the other reacted to his cue. In the event of movement 1) the trigger forward would try to hold the ball or flick it on for the secondary forward. The secondary forward’s movement would be timed to occupy the middle defender of the three chain. This would leave the covering defender on the outside in a weak position to intercept, thus turning a 3v2 into two 1v1s.

In the event of movement 2) the trigger forward would spin into the channel with his body in a position to protect the ball from the defender. From here he could either dominate the resulting 1v1, or play the ball backwards for a quick cross. Meanwhile, the secondary forward would alternate between occupying the central covering defender (Sammer) or isolating the ball-far (Köhler). In both instances of the varied movements, Zidane would join the attack late and enter the box in the area of the free defender. This was an attempt to exploit the potential open spaces created by movement from Boksic and Vieri, and to create a series of 1v1s which the Juventus forwards could use their individual quality to dominate.

Whilst they did achieve vertical progressions, this method of attacking was inconsistent in its results. They created one or two chances, missed by Vieri, but playing the ball forward directly often resulted in imprecise attacks. As a result, players received an unpredictable ball which needed controlling first, or couldn’t be controlled at all. Also, by spinning into the channels Juventus often achieved the vertical progression they desired but at the cost of a negligible angle to goal.This resulted in either a dribble towards goal, a cross or a backward pass for a supporting player (Di Livio) to cross.

Each of these options cost the Juventus attacks the time they had bought with such swift vertical progression, and either allowed Dortmund time to recover or resulted in an aerially capable forward crossing from a difficult angle. In part the speed at which they attacked helps to explain their defensive solidity, with the ball travelling so quickly forward it was impossible for Porrini or Iuliano to contribute to possession play and therefore (with the exception of a few forward runs from Iuliano) they always retained a solid defensive shape.

This was Juventus’ primary avenue of attack and whilst they did put together some pleasing combinations with Zidane acting in the half-spaces as a 10, they appeared far too sporadic to have been planned or trained for. By trying to advance into attack so quickly and setting such store by individualism, Juventus didn’t develop a structure in possession to manipulate Dortmund’s defenders and cohesively open dangerous spaces.

It also prevented their crossing strategy from being as effective as it might have been. More players contributing offensively, would have created different angles and heights for crossing opportunities. This lack of structure also prevented them from counter-pressing as effectively as they might have. Where present at all they demonstrated a man oriented counterpressing approach which was based around delaying the immediate player in possession in order to allow team-mates to recover into defensive shape.

Dortmund’s possession structure

As previously referenced, Dortmund’s possession structure offered little scope to manipulate or shift the Juventus shape to open spaces or create opportunities. They demonstrated no desire to build moves using the theoretical advantage that their 3-chain in defense offered them, and the defenders never dropped into depth to expand the available space to play in. Theresult was an attacking approach largely based around unsupported long-balls and frequent losses of possession.

As a result of the 3-chain holding a defensive line at all times the sixes, Sousa and Lambert, had significantly reduced space to operate in. This, coupled with the tendency that they (along with the wing-backs) had to play along the same horizontal line, completely destroyed the possibility of opening spaces and angles necessary for ball circulation and combinations.

BVB’s defensive approach must also be taken into account when assessing their possession structure. When operating with a man-oriented defensive system, the positioning of the defender is contingent on the player he/she is marking. This means that upon regaining possession, the team will be positioned according to their opponent and not any potential possession structure planned or trained for.

This is likely to harm ball circulation as the network of angles and open spaces required will not be consistently established. Paradoxically though, this reactive defensive scheme and lack of structured attacking shape contributed to the positive result Dortmund achieved. Playing against a Juventus team without a fully established attacking structure themselves, meant that BVB could enjoy the benefits of a man-oriented approach (maximum access and pressure on individuals) without as many of the drawbacks (susceptibility to group combinations and movements).

And so it proved as Juventus struggled to fully manipulate the Dortmund marking through integrated movement. BVB’s inability to fully open spaces to develop possession ensured that when possession turned-over (very frequently) their players were not punished by transitional play as they were often in fairly conservative positions. Again there is a link to Juventus’ lack of cohesive group movements, (Boksic, Vieri and Zidane aside) as they failed to use decoy movements or group combinations to draw defenders into higher positions and open spaces for blindside/off-the-ball runners.

Having to chase the game in the second half, Juventus brought club legend Alessandro Del Piero on. Whilst this made them more potent going forward, it diluted their strengths from the first half and exacerbated their weaknesses. They were increasingly individualistic in offense and more open defensively. Whilst the individualism resulted in a spectacular improvised goal (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QpUoeEL8bTs), the continued lack of structure further harmed their counter-pressing ability.

Whilst the two set piece goals conceded in the first half could be considered unfortunate, the counter-attack they conceded in the second hinted at the flaws in the side. Moving to a 4-2-1-3 weakened the dominance of the centre that they had enjoyed in the first half,this was the crucial factor to their defensive stability in open play. By moving Di Livio to left-back, they removed a mobile defender with excellent anticipation and pressing skills away from the centre, an area of huge strategic importance.

This left Deschamps and Jugovic as sixes and eliminated their ability to screen the centre and execute controlled shifts to pin BVB by the touchline. Allied to the lack of efficient counter-pressing structure or attackers recovering into defensive shape, Juventus had opened an avenue for BVB to attack without creating any significant pattern of offensive combinations.

Therefore it was no coincidence that a Juventus loss of possession from a throw-in which they failed to counter-press effectively resulted in a lateral pass in front of their midfield, a direct pass through the centre and a BVB goal from the move. These conditions simply weren’t present in the first half and as Juventus weakened their control of the centre, BVB brought on Ricken to strengthen theirs (as much as man-orientations allow).

Conclusion

Lippi’s Juventus were a truly impressive side and whilst they may have had their flaws, they were extremely modern relative to their era. Their lack of counter-pressing structure did show in the final but prior (only 1 goal conceded in 6 group games, 4 in 10 games overall) to this it was by no means a clear weakness. In reaching 3 successive finals they were the team to beat in the late nineties, unfortunately for Lippi, an unspectacular Dortmund side that had made a point of practising set-pieces before the game did just that.

James is currently an academy coach at Preston North End and a keen futsal player.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Alex October 9, 2017 um 3:15 pm

Can you do a Retro Analysis about an Arsenal match from the previous decade? The 2006 CL final against Barcelona for instance, although it was somewhat spoiled by the red card.