Team Analysis: Julian Nagelsmann’s Hoffenheim

After 16 games played, TSG 1899 Hoffenheim remains the only unbeaten team in Bundesliga. Apart from having the youngest coach ever in the German top flight, what is so special about the side from Southern Germany?

First to mention, there’s a squad full of interesting player types and enough personnel for different tactical set-ups as well as for position-related changes. Probably thanks to the good periodization regime, no big injury problems have appeared so far. Nagelsmann and his men can solely focus on training at their idyllic complex in the village of Zuzenhausen.

In Oliver Baumann, Hoffenheim has a goalkeeper, who is capable in build-up and also anticipates situations well – essential for an ambitious side. In front of him, there are several solid defenders available that can be effectively used in clearly defined roles. Add to that the fact that Benjamin Hübner has made a few steps forward, especially improved in handling the ball. But without a doubt, Niklas Süle, who will join Bayern Munich in summer, is the most talented amongst the defenders. Although he generally can play good laser passes (fast ground passes) from the back and is also capable of dribbling into space, his decision-making still needs to improve. He generally knows very well when to leave the back-line and shows good abilities when defending proactively, but tends to get carried away sometimes.

As for the wing-backs, the likes of Jeremy Toljan and Pavel Kaderabek can be fielded on both sides. Both are dynamic players, who don’t just hug the touchline, but can also be very good in combinations and offer a certain degree of diagonality. The same is true for the rather dribbling-focused Steven Zuber and above all for summer signing Lukas Rupp. Rupp is a versatile, clever and pressing-resistant technician, who especially fits busy midfield roles very well, just like Nadiem Amiri who focuses more on advanced zones and even a bit more on spacious situations like somewhat of a “running no. 10”.

In contrast, Sebastian Rudy and Eugen Polanski offer more sense for strategy and often play as pivots. Polanski fits the role of an anchor better, whilst Rudy floats around a bit more. Sometimes Rudy can even resemble Luka Modric, so there is little risk for Bayern adding him to their squad as a free agent at the end of the season.

Kerem Demirbay is another interesting midfielder and has been the shooting star so far this season. Already at a less than average Düsseldorf side in second Bundesliga, he showed his promising abilities and his potential that shines brighter than ever now. He embodies more of a playmaking midfielder and possesses great dribbling abilities. Apart from that, Hoffenheim started building their squad for next season with the signing of Austrian international Florian Grillitsch from Werder Bremen – another pressing resistant and provoking dribbler, who could potentially fit in deeper roles, but has to improve his timing when and how he drops back.

Upfront, first of all, Sandro Wagner needs to be mentioned. The Bundesliga veteran is a “mentality player”, as Niko Kovac called him, who’s physically strong and doesn’t fit the profile of striker needed in a possession-based team on first sight. Compared to that, Andrej Kramaric and Mark Uth are two rather dynamic players, who can combine well with the former often being the focal point of Hoffenheim’s attacks. Eduardo Vargas and Adam Szalai also bring exceptional qualities, yet are usually not part of the starting XI or even the squad at all.

Visible principles and stability problems at the beginning of the season

Although Julian Nagelsmann has repeatedly and rightly so referred to certain “principles of play” as the basis of his team’s strategy, he mostly uses two main types of formations: on the one hand several variations of a 3-5-2, on the other hand line-ups derived from a 4-3-3. The latter was used more frequently at the beginning of the season.

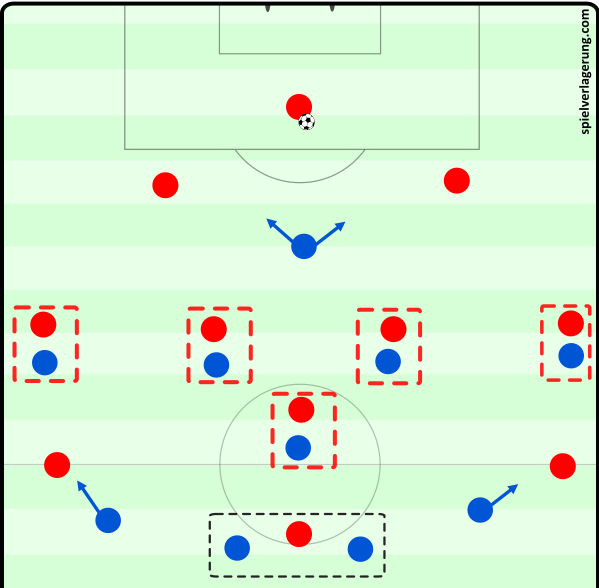

For example, on Matchday three, when Hoffenheim hosted VfL Wolfsburg, they pressed in a 4-3-3/4-1-2-3. Against a typical 4-2-3-1, one-on-ones naturally occur. Especially for the centre-midfielders, this can lead to a man-oriented approach with them being dragged out of their positions too easily. But the same formation can also generate a rather option-oriented approach.

Hoffenheim found itself somewhere in the middle of these two poles. Frequently the wingers Uth and Kramaric pressed the centre-backs from outside, whilst striker Wagner blocked the passing lane to the respective team-mate. Like that, they guided the build-up to the half-space, where they could generate local compactness, forcing the opponents to stay on the wings afterwards. In the course of that, the centre-midfielder from the other side travelled into the ball-near half horizontally – something that is also visible in other formations.

This can lead to great staggering and allow access to the ball, but when it’s not done properly or some unlucky moments appear, the ball-far side can be reached too easily by the opponents. When the ball is played into this area, isolated duels occur and Hoffenheim needs to retreat collectively. In situations like that, a back three/back five would allow a rather aggressive behaviour of the wing-back since there’s one additional player covering at the back.

Against The Wolves, Nagelsmann’s team couldn’t create the desired situations constantly, because the man-orientations became too dominant, with central passing lanes being left open. Subsequently the back four was put into unpleasant situations with attackers running right at them with the ball.

But the back four often behaved man-oriented. Especially when the ball-near full-back pushed higher, the gap between the centre-backs became too big with the ball-near one covering. Because at the same time, the respective centre-midfielder often attacked the opponent’s full-back, a lot of space opened up and the team was often split due to slow shifting. An additional man in the back line would’ve been helpful in those moments as well, especially for defending (diagonal) passes from the wing zone into deep spaces.

Alternatively, Hoffenheim could line-up in a 4-4-2 with one centre-midfielder pushing higher up the pitch, when the opponent’s centre-backs stayed narrower in build-up. Based on shifting mechanisms and man-orientations, this could be transformed into a 4-2-2-2 or 4-2-4, again leaving some gaps to play through. When the team dropped backed, a 4-1-4-1/4-5-1 was formed, which sometimes became a 5-4-1 when Uth moved back on his side.

In possession, pivot Polanski generally positioned himself between the centre-backs to establish a stable ball circulation. At goal kicks, Rudy, playing as right-back, could stay deeper as well. No matter the variation, the space between Amiri and Rupp as centre-midfielders (no. 8), who often approached the last line, and Polanski would become too big. Despite Polanski pushing forward and some of the other players dropping back, important spaces for connecting the team were often left unoccupied. This also had a negative impact on the counter-pressing. But still some promising patterns were already visible.

For example, Kramaric often moved away from his left side towards the ten space, which was balanced by Rupp’s movement or otherwise led to occasional diamond structures in midfield. Furthermore, changes of position took place on the right-hand side. Uth dropped back in half-space, which would be overloaded afterwards. Kramaric joined in, sprinting diagonally to the right, whilst Wagner stopped the centre-backs from moving away. Thereafter the ball could be switched to Kaderabek, who pushed forward on the other side.

Additionally, Wagner was also used as a target man for lay-off passes, which would often be played in different angles or horizontally. Furthermore, Wagner could also protect the ball first to tie opposing defenders before passing to the ball-far, mostly right, side. Lay-off passes could also be used to free and involve Polanski with a good field of vision. Generally, these lay-off passes can mark a point, where Hoffenheim’s approach changes from vertical play in smaller space to pushing forward in a bigger space.

The well-choreographed movements were particularly visible in attacking transitions, which were generally a dominant factor for both teams throughout the game. All too often Hoffenheim’s attacks still ended up on the flanks, from where the ball was crossed into the crowded box. This tendency vanished during the upcoming matches – also due to a change of formation.

The new standard system

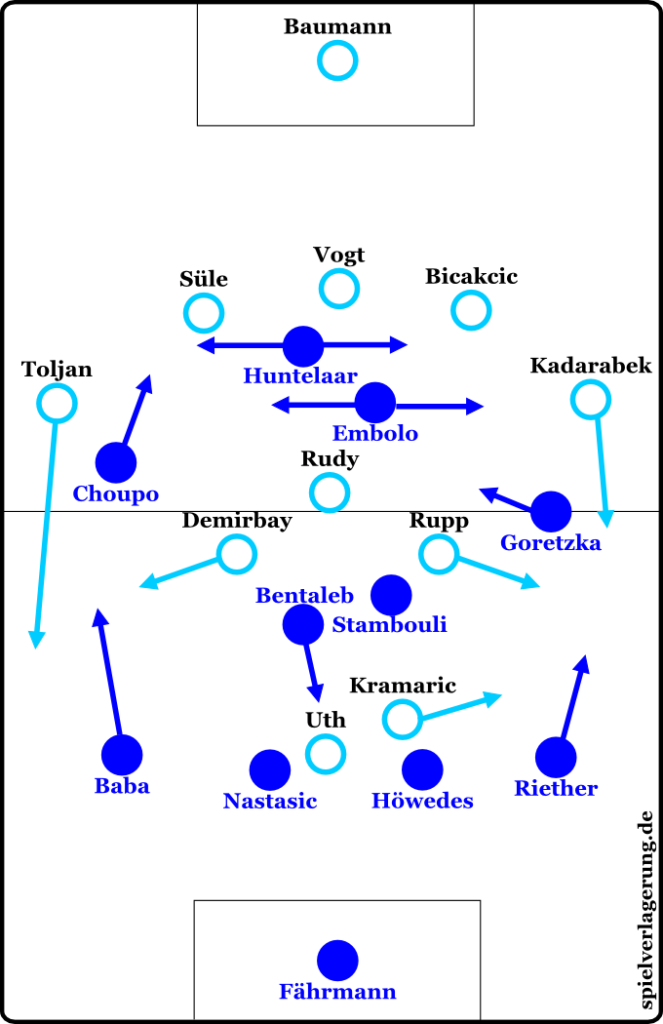

Since the beginning of Nagelsmann’s tenure, Hoffenheim regularly used a 3-1-4-2 formation. In the current version, it made its debut on 5th matchday against FC Schalke 04. From then on, the system was constantly developing further.

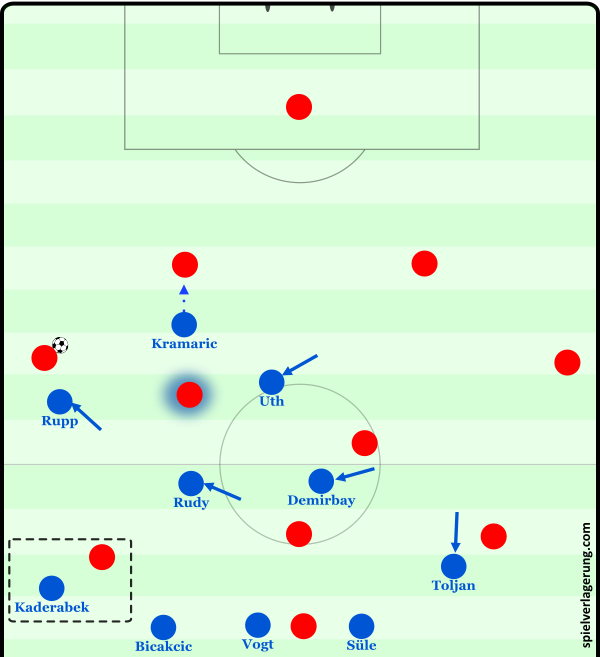

Rudy came back to his natural position and played as a pivot with Demirbay and Rupp in front of him as no. 8s. Toljan and Kaderabek occupied the wings, whilst the back three was formed by Ermin Bicakcic, Kevin Vogt and Süle. Kramaric and Uth started upfront.

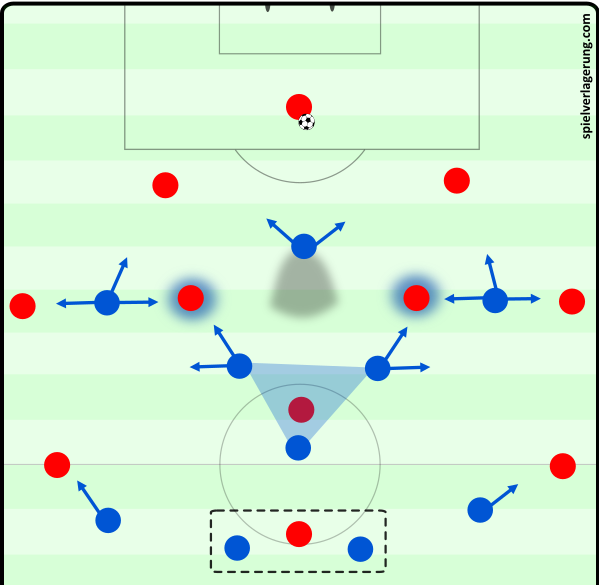

Against the ball, this line-up resulted in a 5-3-2/5-1-2-2 formation with several built-in transformations. Often it worked like a pendulating back four (4-1-3-2/4-3-3), in which the ball-near wing-back pushed higher and the ball-far one moved next to the three central defenders. The weaknesses of the usual 4-3-3 were mostly neutralised and bad decisions by players like Vogt didn’t have an immediate negative impact thanks to the better defensive coverage.

On the right-hand side, Uth attacked the centre-back of Schalke with a curved run to direct their build-up towards the flank. The full-back was the only option left. When the ball was delivered to him, Toljan pushed towards the opponent aggressively, coming far into Schalke’s territory. The exposed space behind him was covered by Süle, who feels much more comfortable in such a role than his colleagues do. At the same time, Rupp could also shift aggressively, which was situationally balanced by a higher positioned Kaderabek, who could then deal with passes to the weak side.

When Schalke started their attacks on the left side of Hoffenheim, Kaderabek acted more conservative than his counterpart. After pushing Schalke to the wing, it was Rupp who pressed towards the sideline diagonally from his central position. On both sides, Hoffenheim built a pressing trap around Schalke’s ball-near no. 6 for a horizontal outside-in pass. Needless to say, that they won the ball like this before the deciding goal to make it 2-1.

In a slightly changed version, these mechanisms were also used against SC Freiburg, who used a back three (3-4-3/5-2-3) themselves. During the pre-match warm up, Julian Nagelsmann spoke to all his players separately to explain their own tactical reaction to each one of them. On one hand, the patterns, once again, varied depending on the side and were adjusted to the particular situation.

On the other hand, Hoffenheim also guided their rivals to the centre of the pitch. The low level of central presence from Freiburg could be used to the home side’s advantage especially by pressing backwards. In the course of this, Rudy played a rather dominant role since his team-mates in the middle often focused on Freiburg’s wider positioned centre-backs – especially when the guests switched sides.

Throughout the game, Hoffenheim also made use of a deeper pressing and focused on blocking passing lanes.

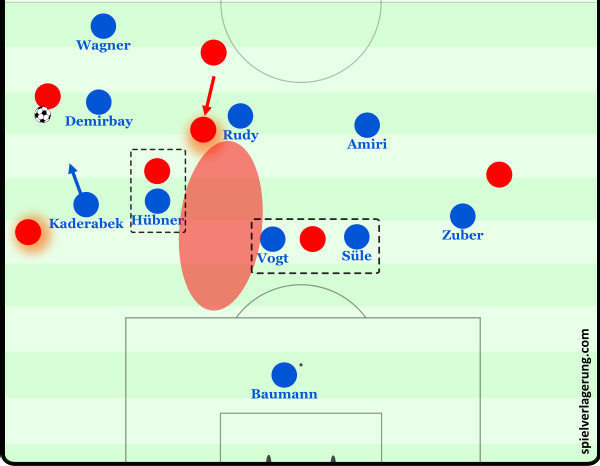

Nonetheless, sometimes the structure in central areas was diminished when Freiburg’s attackers dropped back and caused organizational problems for Hoffenheim’s man-oriented scheme. When they placed passes between the lines, the responsibilities weren’t always clear and some dangerous situations resulted from this. This was an important factor that Bayern exploited in their 1-1 draw with Hoffenheim.

In the following matches, details were consistently changed by Nagelsmann, which made the pressing at times look like a 5-1-3-1/5-4-1. Especially possible pressing targets were changed. Against Leverkusen a big chance occurred right at the beginning, when Julian Baumgartlinger was deliberately left unmarked at first and attacked moments later, when he faced his own goal. The degree of man-orientation varies as well as the wing-back roles change. But the fundamentals always remain the same.

Positional play as engine for further development

Using a back three, and especially with the player roles in front of it, the transition from patient build-up plays to possession in higher zones worked out smoother. Overall, Hoffenheim’s approach resembles a more vertical and dynamical version of the Spanish Juego de Posición.

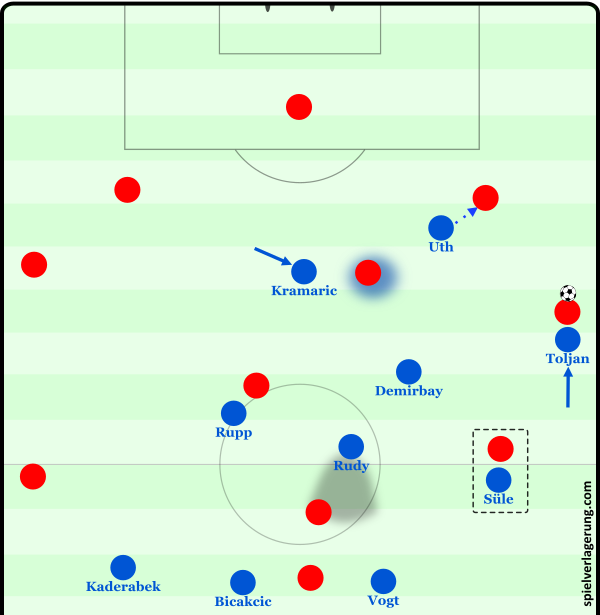

Julian Nagelsmann likes half-spaces. Julian Nagelsmann likes diagonal ground passes through central areas. That doesn’t get along with a formation that includes two wingers on each side, though. Instead, over the course of the season, an increasingly fluid and sophisticated way of giving width emerged. The lateral zones are still used actively and consciously, but the main reference point is always the centre. The strategy is based around the centre. When the opposing players block forward passing options, possibilities arise to play horizontal, yet still flat, passes through the gaps. Afterwards, Hoffenheim tries to re-enter the more important zones.

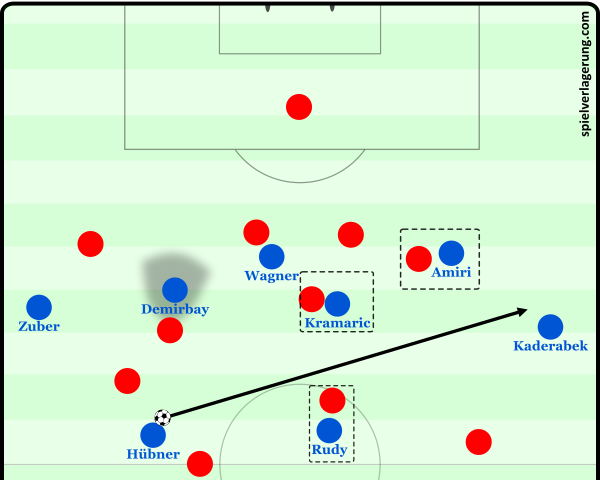

Hamburger SV blocks the preferred options, so Hübner plays a lateral pass between the lines. Unfortunately, it’s not executed perfectly and too much of a surprise for Kaderabek.

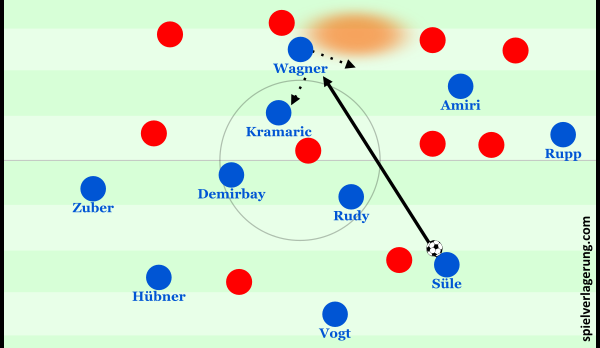

In particular, the dominant display versus FC Cologne in the league showed what the team is capable of. With Polanski as pivot and Rudy as right-sided no. 8, the play in the second third worked out well, also because the centre-backs supported their team-mates by dribbling from the back as well. Süle even passed Toljan in several situations, moving through inner lane. He was usually followed by an marker and helped to push Cologne back. Supporting movement like this is a key component of Hoffenheim’s game and occurs in several variations. Add a good structure for combinations to that and you’ll always have a lot of options to progress the attack.

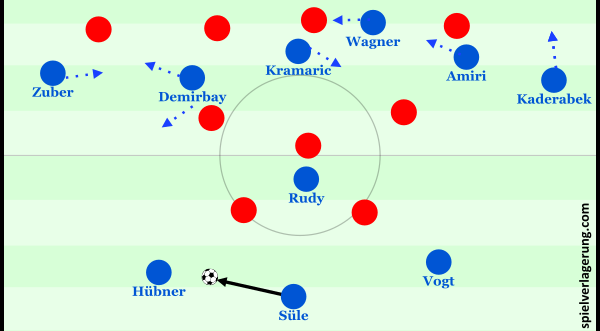

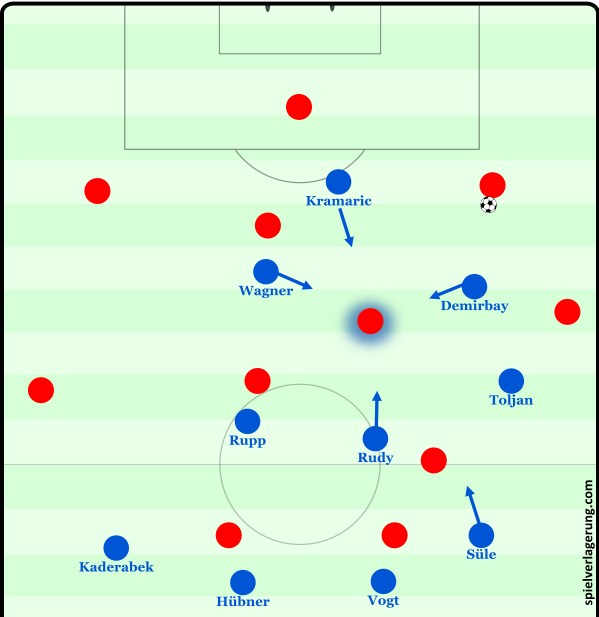

Kramaric drops deep; Hoffenheim has a lot of possibilities to advance to different layers (game vs Freiburg).

On a collective level, they either show calm combination play or focus on fast-paced attacks. It generally gets more fluid, when Kramaric drops back to form a diamond in midfield. Inside the diamond, combinations can take place in a rather tight space, just until a chance occurs to change the focus and switch the ball to another area of the pitch. For example, even the wing-backs sometimes sprint behind the opponent’s defence in such situations.

But also the initial staggering can be more focused on occupying the last line or the space in front of the defence, which is the initial point for positional changes and dynamic attacks.

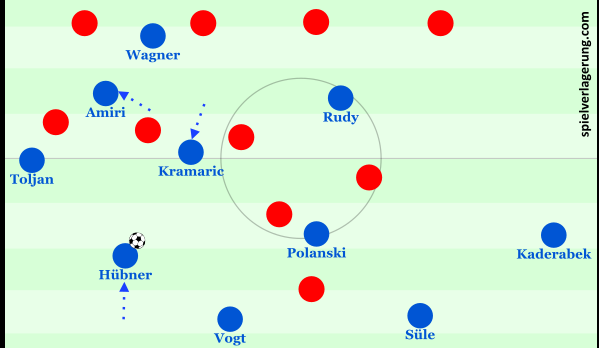

Leverkusen is a man down and lines up in an interesting 4-2-1-2. Hoffenheim focuses on occupying the offside line. Also with the ball you can see different movements for each side here. Some asymmetrical shapes result from this.

It might sound a bit complicated, but in the end it just tells you that combination and dynamic are linked inseparably at Hoffenheim. Based on that, the rhythm can ideally be changed. The core of this is simply mounded out of principles like movement and counter-movement, action of the team-mate and reaction to that.

Examples for this are situations like one from the match against Schalke, when Kramaric, Uth and Demirbay rotated circularly on the right-hand side after receiving the ball from a switch of play. Something similar could be observed against Cologne on the opposite side.

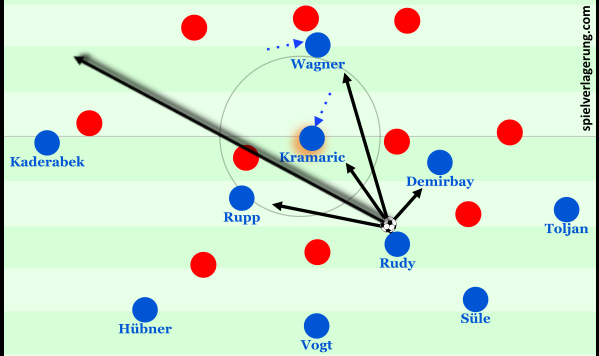

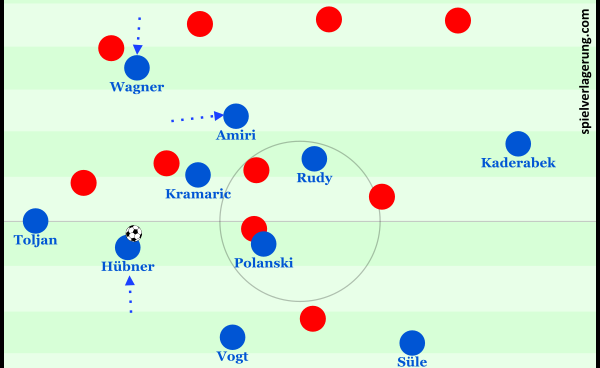

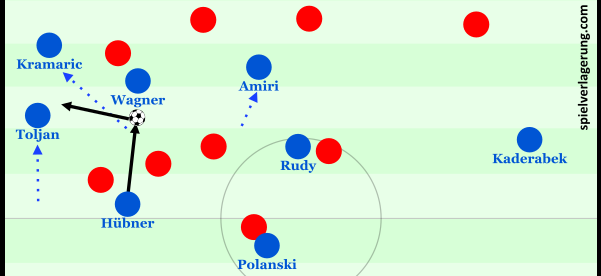

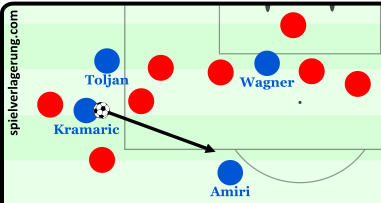

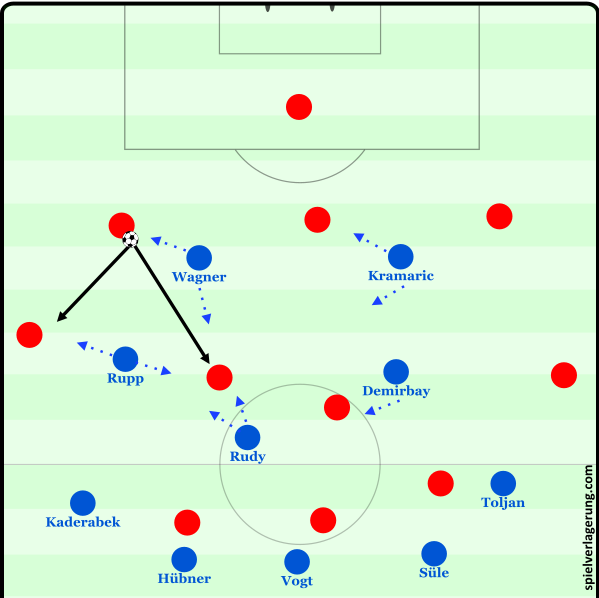

1) Hübner dribbles towards the open space without being pressured. At first, Kramaric drops back, so that Amiri gets out the way.

2) Hübner can advance even further. Amiri moves back towards the centre to open the gap for a pass into Wagner’s feet. Cologne’s defenders focus on Kramaric and Toljan.

3) At the same time, Kramaric starts a run towards the sideline. Cologne’s full-back Frederik Sörensen is in trouble. Wagner can lay off to Toljan who advances as well.

4) Toljan quickly forwards the ball to Kramaric and makes an underlapping run. Köln sits deep at this point. Amiri positions himself just outside the box. He can’t control the ball properly, though. But after that he just runs to the opposite side to draw attention from opposing players, whilst passing the ball to Kaderabek who moves to the inside. Central space opens up for Rudy. Hoffenheim’s attack can continue with Amiri as right-winger.

Conclusion: What can possibly go wrong?

Hoffenheim under Julian Nagelsmann is a good Bundesliga team that plays aesthetic football. That’s what probably all of us can agree on. Still, luck has played a role in their success so far. Many of the ten (!) draws could have or even should have ended in losses. Just like last season, the deeper defending of Hoffenheim can be very chaotic at times and the effectiveness of their counter-pressing is inconsistent.

Man-oriented opponents (Hamburger SV, Eintracht Frankfurt, Borussia M’Gladbach) caused them some problems, when they pressed higher up the pitch. In such situations you can see, that the individual level of the back three is not as high as it should be for a real top team. Against M’Gladbach, Nagelsmann changed the formation a lot, until his team played in a customary back four for the entire second half. Before that Fabian Schär played a mixed role somewhere between a centre-back and a pivot (“switch centre-back”).

Leverkusen (playing with ten men) can exploit Hoffenheim’s man-oriented defense and creates gap easily.

In that match, some serious flaws were visible, which regularly appeared in other matches as well. The distance between defence and midfield as well as between each defender was far from perfect for most of the time. The back line sometimes lacked the appropriate coordination when moving the chains which included wild forward runs. When using a high press, you could still see promising situations.

Hoffenheim is like a surprise bag, of which one knows that at least something good will always be inside. For sure, it will also contain a defeat someday, but even then nothing will go completely wrong on Nagelsmann’s road to glory.

With special thanks to CE!

Read the German version of this article here.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Mr Incredible 11 November 15, 2017 um 11:22 am

Roger Schmidt Leverkusen & Jurgen Klopp Dortmund please. In the some way:

Focus more on the aspect with the ball