Ajax can’t break down stubborn Rostov defence

Rostov return from Amsterdam with what could be a crucial away goal in the first leg of the Champions League Qualification Round. Despite having the ball for the vast majority of the contest, Ajax hosts were unable to turn their dominance of possession into a victory, thanks in no small part to Rostov’s defence.

Rostov’s un-clean implementation of their defensive scheme

For those unfamiliar with Russian football, the sight of Rostov within one round of the Champions League group stages must be a strange one. However, one should not associate the lack of prestige in Rostov’s name and transfer dealings with the idea that the southern Russians do not deserve to be on the cusp of the footballing jackpot that is Europe’s premier club competition.

While they may not share the extravagance of their Moscow or St Petersburg rivals, Rostov have exceeded all expectations largely in part to the work of Kurban Berdyev. The man who previously masterminded Rubin Kazan’s rise in Russian football – complete with victory in the Nou Camp – constructed a formidable defensive system at Rostov which took them on a Leicester City-esque journey, from narrowly avoiding relegation to within a spectacular Igor Akinfeev save of the league title.

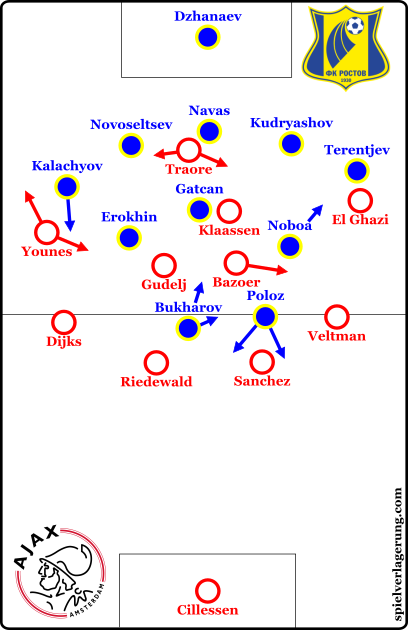

Although Berdyev may have “left” Rostov – in a managerial sense anyway – his system remains. Rostov primarily defend deep in a 5-3-2, using direct balls to quick strikers on the counter. Whilst not being the most eye-catching of strategies, the results speak for themselves, as Ajax found themselves to be the latest victim to Rostov’s stifling defence.

At its core, Rostov’s defensive strategy revolves around ceding the flanks to allow them to control the centre. Hardly a revolutionary idea, “show them outside” is a strategy which is commonly found throughout all levels of football.

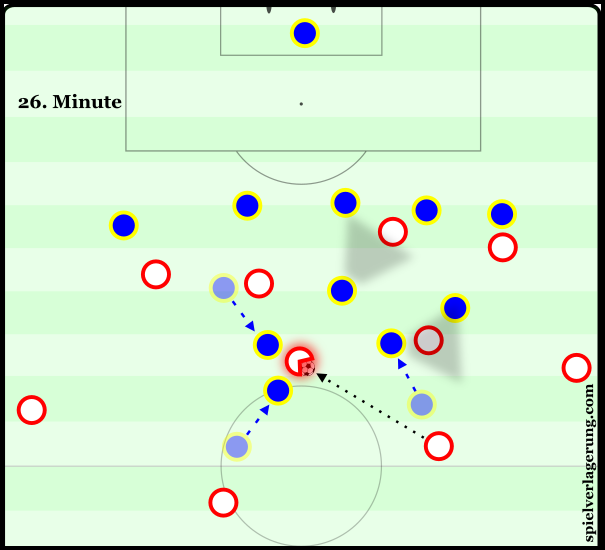

What is interesting about Rostov’s implementation, however, is how committed they usually are to restricting the opposition’s central progression, and they showed this for the most part against Ajax. The two strikers, Dmitri Poloz and Aleksandr Bukharov, looked to block central passing lanes through use of cover shadows, deflecting opposing possession to the flanks from the outset.

Bukharov, however, did not perform this task with the same intensity and diligence as Sardar Azmoun usually does. This made Rostov susceptible to switches across Ajax’s back 4. Through such switches, Ajax were occasionally able to catch Bukharov out of position, and without the pace to get back, this provided a route for the home side to progress through the first line of pressure.

The positioning of the midfield three was also focused on preventing Ajax from playing forward centrally. Instead of defending in a man-oriented fashion to dissuade a certain player from receiving the ball, they were much more structured in their positioning – favouring a more position-oriented approach, from which they could apply immediate pressure to any player receiving in their zone. Such a scheme made it difficult for Ajax to generate and play through a free player through dynamic positioning or rotations, since Rostov’s midfielders were able to maintain access to any potential receiver.

Rostov’s position-oriented scheme allows them to apply instant pressure on an opponent receiving within the block without the risk of being dragged out of position by intelligent movement. They move intensely to cut the opponent’s key passing lanes, leaving him with no choice but to come back out of the block and try to form another attack.

Furthermore, their staggering largely prevented more direct penetrating passes. Key in this regard was Alexandru Gatcan. The Moldovan sat slightly deeper than Christian Noboa and Aleksandr Erokhin at the centre of the midfield three, which naturally made the space to pass through them vertically smaller, and was sure to keep a manageable distance between himself and the ball-near midfielder in order to maintain compactness. Through this mechanism, and by focusing more on his position and passing lanes rather than opponents themselves, he was able to intercept a number of passes, thus creating opportunities for Rostov to counter.

When Rostov were able to successfully deflect Ajax’s build-up to the flanks, they showed signs of their trademark pressing movements. Throughout last season, Rostov’s wingbacks would press incredibly high up with the ball on the flank. Similar to how Italy defended in the recent Euros, they would shift into a situational 4-4-2/4-3-3 depending on how high up the ball-near midfielder pressed too. The aim was for the ball-near midfielder to block passing routes back inside through his cover shadow, while the wingback would apply intense pressure, either forcing the ball-carrier back to restart the attack, or into the back-pressing forward in order to win the ball and spring a counter.

Pivotal to the success of this aggressive approach from the wingbacks is the subsequent action of the ball-near central defender. In order to maintain compactness across the defensive line and to minimise the space behind the pressing wingback, it is vital that he shifts across to cover, and that the rest of the unit follow suit.

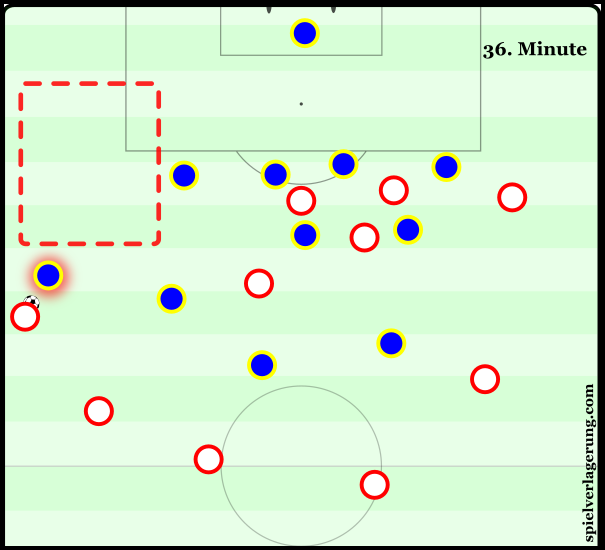

However, in a number of situations against Ajax, this didn’t happen – particularly on their right flank. Veteran Timofey Kalachyov was often left isolated against Amin Younes by his closest central defender, Ivan Novoseltsev. Although Novoseltsev is more accustomed to playing on the left side of the three and was only moved across to compensate for the absence of Lazio-bound Bastos, it seemed puzzling how he could be so adept at performing such covering movements on the left side, and yet leave his wingback so horrifically exposed on the right.

A possible explanation might come in the form of what’s left behind in such movements. Bringing a central defender out to cover a pressing fullback in a back four is considered to be a faux-pas of sorts, since it leaves only one central defender in the box to deal with crosses – the assumption here being that fullbacks are in the main poor at defending crosses. In the back three, however, a covering central defender still leaves two of his partners in the box, and thus the box remains generally adequately protected. The departure of Bastos and the subsequent shoe-horning of Fyodor Kudryashov – usually a left wingback – into the back three, could have explained Novoseltsev’s reluctance to vacate the box to cover the space behind Kalachyov.

That is not to say, though, that the wingbacks were left to their own devices when pressing. The ball-near midfielder would often fill the top of the space behind in what was essentially a quasi-covering movement. The false nature of this cover was such due to the space over which said midfielder had access. While Erokhin often moved closer to Kalachyov as he pressed Younes on the right side, he was not in a position to engage the winger if he managed to dribble past his man on the outside.

As it so happened, this occurred frequently throughout the first half – in particular following Ajax switches. A lack of ball-oriented movement from the Rostov block saw Younes isolated against Kalachyov a number of times, where the German could assert his considerable qualitative superiority on the wingback. The Rostov man at times seemed powerless to stop Younes from drifting past him with ease, which when coupled with the lack of cover, resulted in a number of dangerous situations. Ultimately this ended up in Rostov giving away a penalty, as Bazoer’s shot hit the arm of Cesar Navas after a Younes cutback.

Having seemingly learnt their lesson, Rostov returned to their usual self after conceding. With the outside centrebacks covering their wingbacks much more actively, such isolations were few and far between for the home side.

Additionally, interim manager Dmitri Kirichenko swapped over Noboa and Erokhin. Noboa was much more effective in his defensive contributions than the Russian, who is much better suited to a more attacking role. With Younes causing Rostov so many problems down their right hand side, and with Erokhin doing little to prevent them, it made sense to move him to the other side, and to let the Ecuadorian support Kalachyov instead.

Ajax’s wing focus

An early hallmark of Peter Bosz’s Ajax side has been their proclivity for attacking through the wide areas. With this in mind, and considering Rostov’s defensive strategy, it came as no great surprise that the home side spent the vast majority of the game on the flanks. Unable to penetrate centrally for the most part, they resorted to U-shaped circulation, occasionally trying to force their way through with tight combination play.

The role of Chelsea loanee, Bertrand Traore, was interesting in this sense. While Davy Klaassen would often stay central or even make movements away from the ball, it fell to the Burkinabe striker to move to the ball-near halfspace in order to combine with an inward moving winger. In this respect, his play was impressive, with a nice appreciation for angles and weight of pass, as well as showing an ability to take his first touch on the spin – leaving him facing goal in an instant.

Rostov’s slow ball-oriented shifting after switches resulted in Younes being able to isolate Kalachyov and take advantage of his individual superiority in this situation. The positioning of the rest of the Ajax team is geared towards a cross, placing a huge creative burden on the winger to deliver.

This approach, however, bore no fruit, and Ajax were left resorting to throwing a multitude of crosses into the box. In what became a frustrating affair to watch, deep crosses were favoured even over incisive passes centrally. While quick switches were able to be used to exploit the space of the open side, too often did Ajax fail to capitalise on this, electing to cross early into a crowded penalty area instead of advancing the lines of the team or taking advantage of overloads to burst through. That Ajax’s most dangerous moments came through the individual brilliance of a player substituted after 68 minutes in Amin Younes is a damning indictment of the weakness of their approach, no matter how well Rostov defended.

The behaviours of the home team’s central midfielders did precious little to alleviate their struggles. With Riechedly Bazoer in particular seemingly unable to receive the ball and advance forwards, they spent most of their time in possession switching out to either fullback or winger. Given the profile and positioning of the fullbacks, there weren’t many over/underlaps, which only served to simplify Rostov’s task.

For a team dominating the ball so much, it was surprising to see how reserved and cautious Ajax’s fullbacks were in the build-up phase. Whether unintentional or a tactic designed to provide extra protection for super-direct Rostov counter attacks, what followed was a general lack of opportunities to overload the flanks to take advantage of the sole wingback, further resulting in more early crosses. The numbers with which Rostov defended their box made it exceedingly difficult for the home side to make a breakthrough, and when a chance was created it usually fell under the “half chance” category.

Bosz’s counterpressing starting to take hold

Though it may provide little consolation given the result, Ajax can take pride in their play in defensive transition. Considering Rostov’s strength on the counter attack, stopping it at source was a vital part of Ajax’s game plan.

Despite not creating chances directly through their positional play, it allowed them to counterpress effectively. Through covering space efficiently in possession, the Ajax players already had strong access to the new ball-carrier, or were already in position to recover the ball after it had been cleared away.

Ajax looked to minimise the space around the ball upon losing it. Such a space-oriented pressing mechanic aims to take advantage of the fact that a player who has just won the ball subsequently has the worst view of the field, having spent the previous moments fixated on a particular player or the ball. With reduced situational awareness, this makes him particularly susceptible to pressure as he looks for an exit route for the ball. With enough bodies pressing with enough intelligence, it is possible to severely restrict the ball-winner’s ability to play a dangerous or even accurate pass.

Particularly impressive was their collective intensity in their counterpressing. They were able to achieve great levels of compactness both horizontally and vertically very quickly upon losing possession – again in part due to their strong positional structure. While it did falter a handful of times, the signs for Ajax in this respect are good – even if some serious work is required elsewhere.

Conclusion

Rostov came to Amsterdam hoping to avoid defeat and to return with an away goal at best. Unashamedly reactive in their play, they played exactly as a team with such aims does. Though it was not a victory for the purists, the Russians surely won’t care, and they’ll fancy their chances of shutting up shop in the return leg. Ajax will perhaps feel hard done by, as they came up against goalkeeper Soslan Dzhanaev in inspired form. However, to blame what is undoubtedly a poor result for the Dutch team on a solid goalkeeping performance would be disastrous, and would see them struggle in Rostov.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

Gwen August 22, 2016 um 4:28 am

Thanks lots, great article.