France withstand German barrage to advance to final

Hosts France will join Portugal in the final of Euro 2016 after a 2-0 victory over Germany. Despite the Germans’ dominance for most of the game, Joachim Low’s side were unable to find a breakthrough in Marseille, and instead found themselves crashing out of the tournament they were so heavily fancied to win.

Germany’s midfield staggering

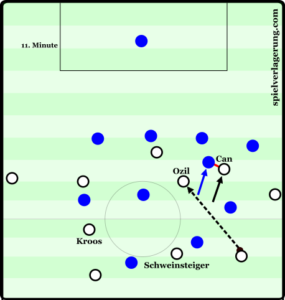

Germany returned to a 4-3-3 after playing with a back three against Italy. Playing with a double pivot in the quarter final, they lined up with what appeared to be three such players in Bastian Schweinsteiger, Toni Kroos and Emre Can, who made his first appearance of the tournament.

Their positioning, however, did not reflect this as the midfield three were very clearly asymmetrically staggered. Schweinsteiger would drop between the Jerome Boateng and Benedict Howedes to form a situational back three, Kroos slid into the left halfspace in front of France’s block, while Can took up a much more advanced position in the right halfspace.

This had a number of effects. Since France defended initially with a 4-4-2 block, Schweinsteiger’s creation of a back three resulted in a much more stable first progression, with Germany holding a straight numerical advantage in that stage, without even having to use Manuel Neuer. With the front two taken out of the equation, the staggering of Kroos and Can came into play. By positioning themselves at such different heights on the pitch, they looked to unbalance the French midfield. If they wanted to press Kroos without disconnecting themselves from each other, Paul Pogba and Blaise Matuidi would have to cede a large amount of space between the lines to Germany’s more advanced players. Alternatively, to reduce said space, they would be unable to maintain access to Kroos – a very bad idea.

There were ramifications for their forward play too. With Muller’s somewhat liberal interpretation of the number 9, Can was able to “fill in” the gap left behind through his positioning high up the pitch and his vertical running. While this role was more commonly performed by Draxler, the movement of Can beyond the defensive line provided Germany with some much needed depth.

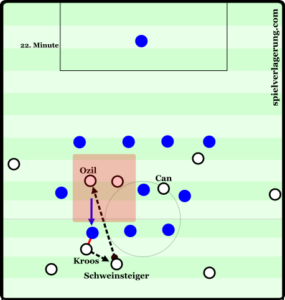

Can’s advanced positioning allowed Ozil to move into more central areas to combine with Draxler and Kroos.

Can’s advanced positioning also gave Mesut Ozil a lot of freedom in his movement. With the right halfspace being occupied high up the pitch, the Arsenal man could drift infield without negatively affecting the team’s positional structure. Given that his ability to link up with teammates in tight spaces is far stronger than Can’s, it made sense to have Ozil in a more central position when in organised possession. Moreover, having him move into those areas instead of starting there made him more difficult for the French midfield to pick up, especially since he’d often move from blind-spots behind them.

Domination without penetration

Ozil’s movement infield helped Germany dominate possession, especially through the left halfspace. Moving into that area gave the Germans a strong presence between the lines of France’s block. This movement, coupled with the numerical advantage they already held over the French in midfield, gave Germany many options to progress through the left side.

The role of Toni Kroos, in this regard, was particularly impressive. One has come to expect that Kroos will dominate whatever area of midfield he plays in, yet his ability to attract pressure before exploiting the space left behind, causing France’s midfield great concern, was masterful. To show such pressing resistance and not only maintain possession but to be proactive and incisive with it is indicative of what makes the Real Madrid midfielder one of the world’s finest. It came as no great surprise, therefore, that some of Germany’s most threatening moments in the first half came through Kroos on the left side. His vertical running and combination play caused the French some moments of panic, while his passing to players between lines – especially Ozil in the initial stages – was potentially dangerous, though the receivers of such passes were rarely able to consolidate the attack by turning and attacking the defence directly. Although credit should be given to the likes of Matuidi for his excellent anticipation in such situations to be able to cover these areas from unlikely positions, often the attacks were diminished in their effectiveness by a proclivity to play the ball wide to the flank rather than to diagonally attack the goal.

Can’s movement complemented Ozil’s nicely, as the Arsenal maestro profited from the space his compatriot created through his movement.

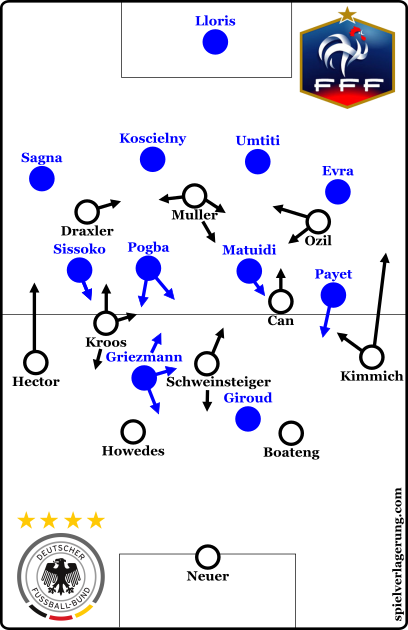

This flank focus from Jogi Low’s side was rife throughout the game. With Jonas Hector and Joshua Kimmich holding Germany’s width from their very advanced “full-back” positions, they were often called upon to take the reins when their midfielders failed to progress centrally. The result was a lot of circulation around the front of France’s block from side to side, and a greatly augmented responsibility on the two full-backs to provide attacking opportunities. With neither Hector nor Kimmich being particularly noted for their 1v1 dribbling or their crossing abilities, this led to a largely ineffective spree of crosses. Furthermore, Didier Deschamps’ decision to play with a 4-4-2 out of possession greatly hindered Germany’s ability to attack through the flanks. While Dimitri Payet had minimal defensive responsibilities, he was nonetheless able to assist Patrice Evra in dealing with the threat of an advanced Kimmich, even if it were simply to cover the halfspace to allow the Juventus full-back to press his opposite number more aggressively.

The approach to dealing with Hector differed considerably. Left unchecked by Moussa Sissoko in the opening stages of the first half, Hector was able to recycle possession easily through Kroos in particular – such an option was not as readily available for Kimmich on the right side, due to Can’s positioning near the offside line. In response to this, Didier Deschamps altered his defensive scheme slightly. Early in the first half, Sissoko clearly shifted his primary reference point out of possession from the position of Pogba to that of the German left back. In doing so, he was able to reduce the effectiveness of Hector in circulation, however, this came at the cost of compactness in the French midfield. Since Hector was normally positioned so high up the pitch, by defending in a man-oriented manner against him, Sissoko would drop into the defensive line, creating a situational back five. By being drawn into the offside line, he was taken away from the area in which Toni Kroos operated in, which in turn gave the German much more space to play in.

France’s defensive response

In order to combat this newfound space Toni Kroos was operating in, Deschamps made another adjustment. While the French block was set up in order to maintain access to Kroos – and to a lesser extent Schweinsteiger – neither Olivier Giroud nor Antoine Griezmann had great success in this regard. Griezmann positioned himself on Kroos’ side out of possession but was too infrequent with his pressure to hinder the German midfielder significantly.

Germany were able to exploit the space between the French lines due to their midfield staggering. Kroos’ ability to “fix” an opponent to him by just standing still, combined with his ability to play the ball intelligently under pressure helped carve the French midfield open.

While this was almost certainly to ensure that he was always in a position to counter attack if his teammates were to win the ball, it did little to prevent Germany from dominating the game – especially when Sissoko left his right-midfield position. In response to this, Griezmann picked up Kroos much more frequently. This took the Atletico Madrid forward into the area Sissoko had vacated, creating a situational 5-4-1.

Now defending with a de facto back five, France were able to be more defensively flexible. Whilst being largely unable to prevent initial German penetration between the lines, holding free players in the defensive line gave France the freedom to press these receiving players much more aggressively. This was particularly visible in Bacary Sagna’s play. Pushed into the halfspace by Sissoko’s marking of Hector, Sagna was perfectly placed to intensely pressure any German player looking to receive in the area in front of him. In doing so, he was able to prevent players from turning, thus forcing them away from the defensive line.

The role of the French central midfield was similarly crucial in preventing easy German progression. Despite defending in an almost constant state of numerical inferiority, Pogba and Matuidi’s display of damage limitation was admirable.

Their option-oriented approach was key in this regard. By focusing their positioning on the passing lines between German players rather than the players themselves, they were able to press the ball carrier whilst also preventing passes behind them. In doing so, they were able to at least make inroads into the numerical disadvantage, since one of them could effectively limit two German players – as long as one of them wasn’t called Toni Kroos.

French counter attack

Whilst their soaking up of German pressure was impressive, it was the French counter attack which caused the most problems. The option-oriented defending of Pogba and Matuidi was conducive to this. Since, by definition, they weren’t positioning themselves next to a German player most of the time when out of possession, they were instantly available in the transition phase.

Similarly, the lack of defensive responsibility for the forward players left them open when their teammates one the ball. Payet and Giroud, in particular, both performed minimal defensive functions against the ball – the latter not tasked with tracking the forward runs of Kimmich.

It was in this aspect that France were able to achieve success. With Germany committing both fullbacks so high up the pitch, there were great swathes of space on the flanks to be exploited in the transitions. Schweinsteiger, not as mobile as he once was, was unable to cover the vast area needed to prevent France from countering through strong dribbles from Pogba, Matuidi and Sissoko through the middle, or through diagonal passes to Griezmann or Payet on the flanks. Through these mechanisms, France were able to directly attack the German defensive line, with not too unfavourable numbers.

Despite France’s prowess on the counter attack, they were aided by some poor German positioning in possession. By committing so many players forward, they were naturally at a disadvantage in the moment the ball was lost. Poor spacing around the ball in possession – especially in the second half with too many players on the offside line – translated to insufficient access to counterpress in transition. Between these two factors, France were able to impose their counter attack game with much greater authority than Germany could their possession play.

Conclusion

At full time the prevailing feeling seemed to be one of disbelief. In a season strewn with surprises, it should in theory no longer be a shock when a team absorbs so much pressure and manages to win with a counter attacking style. However, the extent to which Germany dominated the ball and forced France into the deepest of blocks was not reflected at all in the score-line.

On reflection, France deserve to be contesting for the European Championship, there’s no doubt about it. Not only did they withstand a barrage that few have managed to contain, but they complemented it with an electric counter attacking game which unsettled the Germans greatly.

The goals might have been fortunate, but certainly deserved.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen