Strategically superior Wales advance

Wales and Belgium contested the second quarter-final of the 2016 European Championship in Lille on Friday evening. Throughout the tournament Wales have established a reputation as one of the strongest outfits in the competition from a tactical perspective. Belgium on the other hand are rightfully seen as a case of misguided talent as they frequently fail to show the levels of performance their players are capable of.

Wales’ defensive scheme

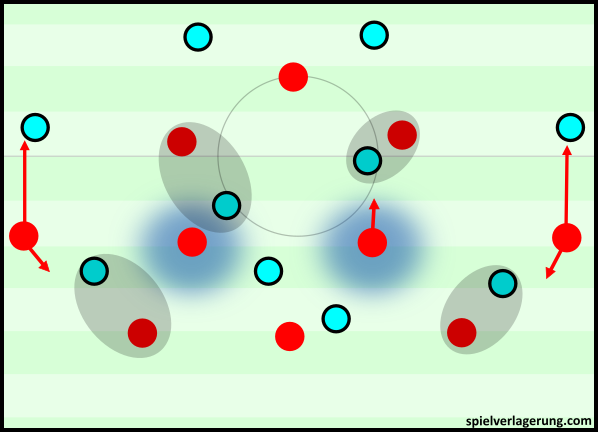

For much of the first half Wales displayed the type of competent defensive organisation that has helped them reach this stage, and limited both the number and quality of chances Belgium were able to create. Their flexibility in such phases has been fairly well documented but it is interesting to analyse exactly what instructions lead to these smooth transitions between defensive shapes.

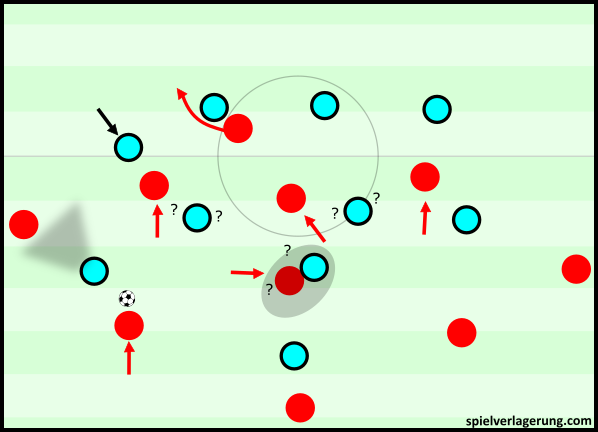

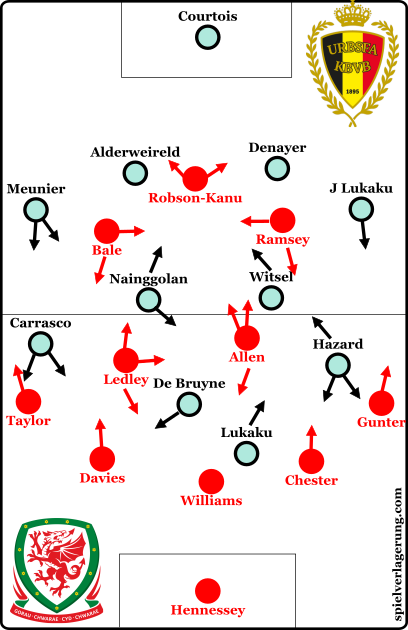

The role of the forwards in Belgium’s early build-up was twofold within Wales’ base 3-4-3 defensive shape. Firstly they were tasked with limiting the influence that Belgium’s holding midfielders could have in build-up. This objective was achieved in different ways. At times they could be seen maintaining distances between themselves and their opponents that would allow them to instantly move forwards to intercept passes or pressure Witsel and Nainggolan when receiving. This was done to allow them to maintain access to Belgium’s centre backs at the same time as their primary objective.

On other occasions the responsibility fell to Ramsey and Bale to mark them, however when combined with their secondary roles this created some issues. Within their base formation Wales’ wing backs were the only ones occupying the flanks both in possession and out of it. Without effective balancing movements in defence opponents could target the wing-backs and play around them.

Therefore in Belgium’s early build-up Bale and Ramsey at times had to slide across to prevent the Belgian full-backs from advancing until the ball-near wing-back had pushed up to take over. On a couple of occasions early on Taylor and Gunter were too slow in pushing up against Belgium’s full-backs. This made Bale or Ramsey have to slide across leaving the Belgian holding midfielders free to receive passes from these wide areas. This was rather quickly rectified with the Welsh full-backs adopting higher starting positions allowing them to move forwards quicker. In these moments the side backs would mark Belgium’s ball near winger tightly and the rest of the back line would shuffle over to create a situational back four.

In deeper defensive phases their shape fluctuated again. Ramsey and Bale now had differing roles. Whilst Bale was relieved of a lot of responsibility instead looking to take up positions from where he could be effective on the counter attack, Ramsey took up increased responsibility. He would now join the midfield line and when Belgium attacked down Wales’s right he was responsible for shifting wide to support Gunter against Belgium’s wide players. When the ball was on the left, Ledley would move wide to support Taylor and Ramsey would then shift inwards to act as an additional midfield player. In these phases Wales would thus move into a 5-3-1-1 as they aimed to maintain access in wide areas and retain the presence in the box to defend securely against crosses.

Although Wales showed their defensive competence they were no doubt helped by Belgium’s struggles in their build-up and general circulation. One of the main issues was the positioning of Nainggolan and Witsel particularly in relation to the centre backs. They struggled to create triangles between them with the midfield pair not staggering themselves particularly well thus the passing lanes from the centre backs into midfield were largely vertical and easier to either prevent or defend against.

These clear responsibilities in different defensive phases allowed Wales to shift seamlessly into more situationally-optimal structures.

Belgium’s offensive wing-orientation

With their attack being so heavily reliant on their individual talents, the positions of Hazard and Carrasco on the wings and their poor structuring in midfield it was no surprise to see Belgium focus on the wings to break through the stubborn Welsh defence.

As Wales played with wing-backs Belgium aimed to create situations whereby they could isolate Wales’ wing-back against their ball-near winger and full-back and use this to create crossing opportunities. Of course Wales aimed to prevent this through the work of Ramsey and Ledley shifting wide to support the effort. Furthermore the ball-near side back would mark Belgium’s nearest winger in these phases. Belgium therefore found it difficult to create these situations that they aimed to.

They did however manage to create these situations after switches. Whilst Wales’ ball-near side back could maintain coverage of Belgium’s winger, the ball-far side back was responsible for assisting the cover in the box that would allow this mechanism to be executed securely. Belgium could thus switch the ball to their ball-far winger and with the assistance of the onrushing full-backs could create the crossing situations that they sought to.

Wales’ midfield rotations

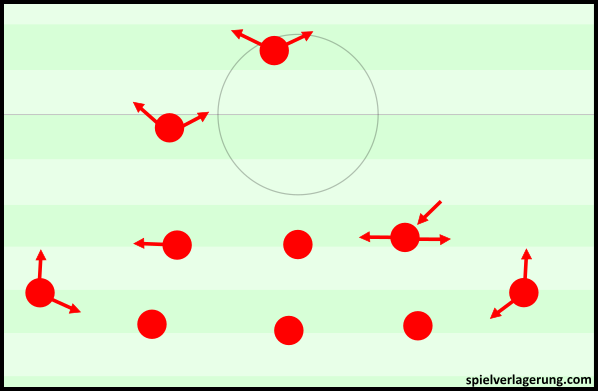

Wales’ flexible structuring was not limited to their defensive phases as they displayed similar levels in their possession game. At the heart of this flexibility was their rotations in midfield. In possession their base shape was a 3-4-2-1 Ledley and Allen as a double pivot whilst Bale and Ramsey acted as 10s.

During their possession phases however Allen and Ledley frequently swapped positions with the 10s ahead of them. Against their often man-oriented opponents these midfield rotations were quite effective as a collective dismarking tool. Indeed with Wales’ frequent positional changes Belgium experienced some difficulty in organising their coverage.

However these movements did not always seem to be very strategic which was evident for a number of reasons. One of these reasons can be summarised with the old adage “if it ain’t broke don’t fix it”. With Lukaku often focused on cutting the connection between Wales’ centre backs in an attempt to halve Wales’ available playing field, De Bruyne was left on his own to cover Wales’ double pivot. Thus Wales initially found it easy to progress their build-up into midfield, as either of the pivots would often be available for a pass. Although Nainggolan at times pushed forwards to try and prevent these simple progressions the constant threat of Bale and Ramsey behind him was enough to cause hesitance in these movements.

However later on Wales seemed to rotate more often into a 3-3-3-1 in their build-up with Ledley increasingly acting as a single pivot and Allen moving forwards to the ten space in line with Bale and Ramsey. This suited Belgium more and De Bruyne found it somewhat easier to cover the movements of Ledley as a single pivot. If the midfield rotations were aimed at creating a free man to progress the build-up why did they change to a single pivot when the double pivot was doing the job well?

Another reason the movements did not appear to be very strategic was that although they were effective at creating separations from markers they were not always used in these situations. At times Allen and Ledley would swap positions with Bale and Ramsey despite not being marked at all. This demonstrated that dismarking was not the primary reason behind the positional rotations and instead may have been the result of an instruction as simple as to keep moving.

What was more impressive was the role of lone forward Robson-Kanu. He was tasked with assisting the creation of overloads and space for the midfielders indirectly and did this in different ways. One way he achieved this was by positioning himself in between the two defenders closest to the ball and pinning them back. In doing this he aimed to create confusion about who would mark him which could increase the time for the midfielders to operate. If he managed to prevent the ball-near midfielders from stepping forwards to join the midfield Wales could enjoy a 4v2 advantage in midfield.

Another way he sought to achieve this was by signposting the threat he posed if they stepped forward. When either of the defenders besides him stepped forward, Robson-Kanu would run into the space they just vacated with the midfielders aiming to play him in. This was done with the aim of making Belgium’s defenders think twice about stepping into midfield.

In-game developments/2nd half

Perhaps after realising the effect it could have Belgium began pursuing their switching strategy more vigorously after half time. With this they began the second half on top and created some of their better chances in the game with Lukaku in particular guilty of missing a great chance. They benefitted somewhat from Wales’ preparation for offensive transitions. With Bale and Robson-Kanu remaining relatively high the gap between Wales’ midfield and forward line was fairly large and most of their switches went through these zones.

On a couple of occasions Bale could be seen joining the midfield line and creating a 5-4-1 which could theoretically have given them greater width coverage whilst maintaining similar compactness levels. Later on however, particularly after taking the lead Bale and Robson-Kanu were still positioned as a front pair but acted far deeper just in front of the midfield line.

This had the effect of blocking the zones that Belgium were using to switch and create space for crosses. It is difficult to tell whether this was a deliberate ploy or simply the result of increased caution once they had taken the lead.

Although the introduction of Fellaini initially moved De Bruyne to a right wing spot he later swapped with Hazard and took on a more variable role as a nominal left winger. From that position he regularly moved infield to help offset the limitations of the Fellaini, Witsel, Nainggolan axis.

With time running out and Belgium staring down the barrel of defeat Wilmots threw on another forward with Mertens replacing Jordan Lukaku. The desperation was evident and the structures were unclean but the resulting switch to 3-3-3-1 gave them a more consistent presence in the half spaces.

Conclusion

Despite largely inferior resources in playing staff to many opponents Wales are through to the semi-finals and the Welsh faithful may just be starting to dream of the seemingly impossible. Their continued presence in this tournament is in no small part due to their strong structuring, particularly defensively. They will fancy their chances against a Portugal side without a win in normal time despite the absence of Ramsey through suspension.

As for Belgium they will be disappointed with the comfortable margin of victory for their opponents. Perhaps they can take some consolation in Wilmots’ position as head coach being seemingly untenable.

1 Kommentar Alle anzeigen

WB July 3, 2016 um 3:06 pm

Great analysis! Really provides a lot more to think about and look for when watching these games. It will be interesting to see how Wales attacks with Ramsey out of the semifinal.