Half-time switches drive French comeback win

The Republic of Ireland booked themselves a place in the first knockout round of Euro 2016 with Robbie Brady’s last-gasp winner against Italy. Despite unimpressive displays from hosts France during the group stages, the Irish were still heavy underdogs to progress to the next round.

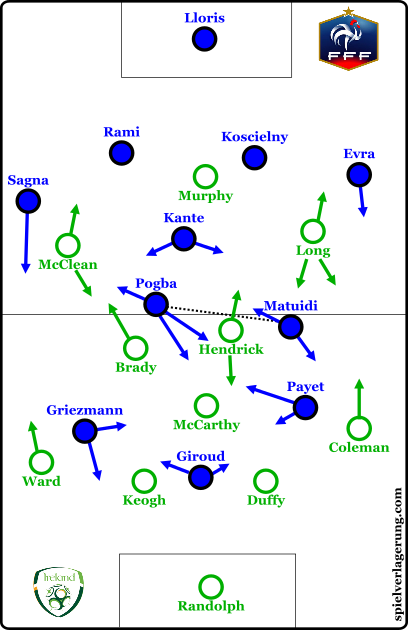

Lineups

France called upon the same personnel that had opened the tournament against Romania, with Paul Pogba and Blaise Matuidi initially switching sides in midfield. Dimitri Payet and Antoine Griezmann were labelled as wingers on paper, but spent large periods of time away from their allocated zones.

Ireland were unchanged from their last group game against Italy, but opted for a system they had not yet utilised at the tournament thus far: a 4-3-3 with Shane Long starting on the right. James McCarthy was moved into a deeper midfield role, and was accompanied by Jeff Hendrick and Robbie Brady.

Irish right-side focus

The opening moments of the game were chaotic, with a number of French individual errors culminating in Pogba tripping Shane Long inside the box. Robbie Brady swept the penalty in off the post, and the following minutes were chaotic due to the unexpected nature of the goal.

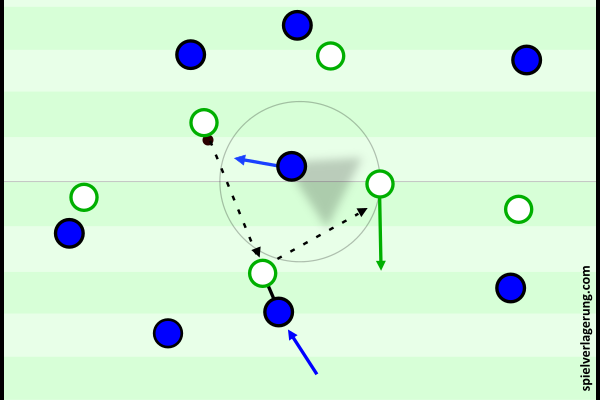

Once each team regained composure and began implementing their respective game-plans, it became clear that the Irish were focusing on long balls towards France’s right side. The target for these were often Murphy, who would drag Koscielny away from the centre to contest the header. Shane Long would make the underlapping run at speed, staying a few yards ahead of the man-oriented Evra due to his knowledge of the scene about to unfold and strong agility & acceleration. He would then attempt to retain possession after the flick-on and move into the box diagonally to allow his teammates to progress towards play. Hendrick was tasked with moving forward, so even if Koscielny won the aerial duel with Murphy, the ball could still be regained. The rest of the midfield would then pendulate accordingly.

Most of these passes came after an initial attempt at building play from Ireland, which was quickly shut down by a French press. Even when there were central passing options available to the Irish defenders, they preferred to pass back to the goalkeeper or pass long themselves. This lack of build-up focus and sustained possession meant Darren Randolph had more passes than any of Ireland’s outfielders, but also the lowest pass accuracy in the team.

French fluidity without clinical decision-making

Much of the Irish defensive scheme was based on man-orientations. This was a particular focus when a second ball had been lost, and the team was attempting to regain defensive structure quickly. Instead of immediately retreating or actively counterpressing, each player would orient to his direct opponent.

As man-marking tends to do, this created large spaces in midfield. Early in the game, France tried to take advantage of this with Payet dropping into a deeper role and Pogba underlapping onto his favoured left-side. But as time wore on, these movements became less organic – the French players simply occupied different roles than they were initially positioned in, without sharp movements to manipulate the Irish defense. Payet and Griezmann often chose to drift inside between midfield and attack, but poor decision making in France’s build-up meant these passes were often not completed.

When a French player was occupied in a 1v1 duel with an opponent, one of the Irish forwards would attempt to provide immediate support whilst closing the backwards passing lane. Long particularly gave Hendrick good support by tracking backwards whilst also ensuring his duty in closing the passing lane to Patrice Evra was maintained. This was useful when the Irish back-four pendulated, as was often the case when Payet dropped deeper to receive possession with his back to goal.

Deschamps activates Griezmann beast mode

France began to gain control in the minutes before half-time. Pogba often received the ball on the half-turn in more space, and used his strength and skill to win a number of 1v1 duels. But primarily the indentation of Payet and Griezmann created the opportunity for third-man runs with Olivier Giroud.

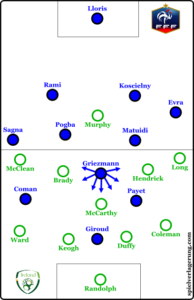

At half-time, France made a tactical change: young winger Kingsley Coman came on for N’Golo Kante. Paul Pogba and Blaise Matuidi were now the two deep midfielders. Matuidi was given the same license to move forward as previously, despite the departure of Kante, and Pogba was tasked with sitting in an unfamiliar deep role.

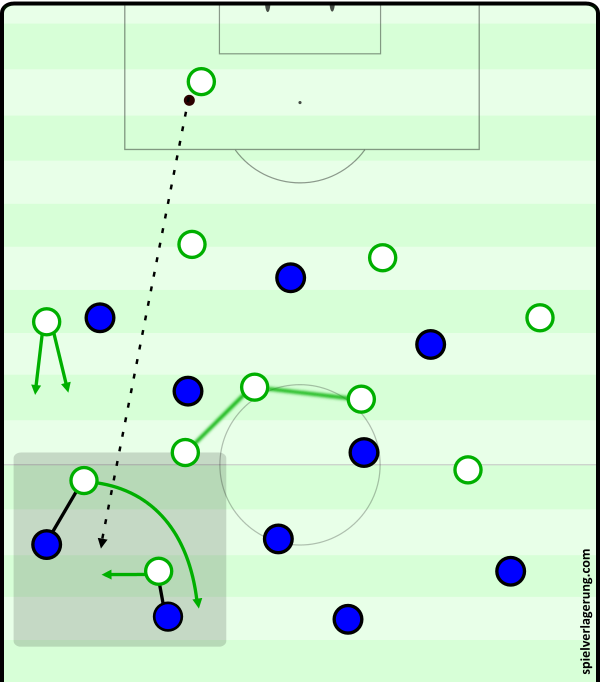

This new midfield composition naturally created more space for opposition transitions, and Irish forwards became able to drop into this space and play a quick wall pass to a teammate. This was particularly effective when moving from right to left, with Pogba drifting that way to cover for the out-of-position Matuidi.

Ireland began pushing forward at speed after half-time, with some quick combination play behind the French midfield

But more importantly, this midfield make-up allowed Griezmann to play centrally, behind the striker. This new freedom meant he could move to all sides of the pitch, and particularly impact the game in the halfspace where he was a key middle-man in wide French combination plays. He acted as a ‘helper’ in build-up, drifting towards the ball-side halfspace and quickly offloading it to a third-man runner. If there was not a suitable support structure available, he made the decision to make a sharp movement into an advanced area rather than receive the ball in a standing position with his back to goal. This intelligence culminated in France’s first goal, which he played a key part in creating before heading goal-wards himself.

Griezmann’s link-up play with [and movements beyond] Giroud were perhaps even more influential than his play deeper in the pitch. Giroud consistently offered himself as a wall passing option throughout the game (as is one of his major strengths), but only in the second half was there a teammate to receive the pass. For France’s second goal, Giroud expertly manipulated Ireland’s tendency to man-orient, as he dragged both Irish central defenders into the same zone before heading the aerial pass to Griezmann for a one-on-one with the keeper.

This influence was perfectly illustrated when Ireland’s Shane Duffy received a red card. Griezmann regained the ball in his own third, and was through on goal less than ten seconds later.

Despite an excellent first-half performance, Jeff Hendrick seemed to tire later on. Whether this was due to fatigue or injury is unclear, but it had a big effect on the Irish defense. He was seemingly no longer able to make as many small alterations to his positioning to adjust to Griezmann’s constant movement and activity. This created the effect of a French midfield overload, despite Kante being removed for a winger at half-time.

Conclusion

With their additional few days’ rest, and extra man on the pitch, the rest of the game was comfortable for France. Ireland re-structured into a 4-4-1 formation after the red card, which made pressing very difficult and was simply avoided by France with a quick horizontal shift in play.

Ireland spent much of their preparation and gameplan focusing on man-orientation, and these tendencies still existed even when down a man, which obviously created disastrous consequences. They had no way to win the ball back in a structurally sound way, and the chance of scoring an equaliser was negligible.

The performance of his team after half-time will create a selection headache for Didier Deschamps. Operating with Pogba and Matuidi in midfield gives very little stability, and it’s possible that Griezmann’s second-half impact was heightened by his Diego Simeone-induced fitness levels. A team with more tools to move through the midfield, as Iceland & England both do, would provide a significantly harder challenge.

2 Kommentare Alle anzeigen

John Franklenson July 3, 2016 um 10:49 am

What is a wall pass?

EA July 3, 2016 um 11:30 am

Where a player uses the pace of the ball from the initial pass to make a first-time pass to a nearby teammate. As if the ball were being deflected back off a wall, with no additional power supplied by the second pass.