Poor central structures lead Switzerland to loss against Poland

Switzerland and Poland clashed in the first knockout round of Euro 2016, with neither team making any dramatic changes to their starting line-up or system. With both sides emerging on the easier side of the knockout tree, this represented a pivotal opportunity for each to kick on and make a deep run in the tournament.

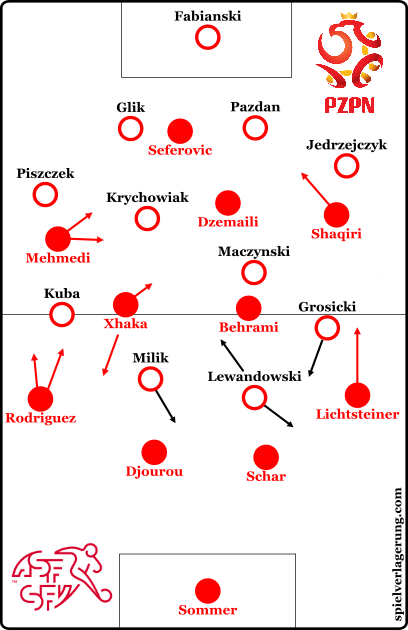

Vladimir Petkovic continued to utilise Blerim Dzemaili in the role behind the striker, but opted for Haris Severovic over youngster Breel Embolo to lead the line. Poland made a number of personnel changes from their 1-0 win over Ukraine, but opted for a similar system.

Shifting build-up focus

The Swiss almost gifted Poland a goal in the opening minute, when a poorly-weighted back-pass from Johan Djourou was nearly intercepted by Robert Lewandowski. Xhaka dropped into the backline, but without suitable horizontal spacing – this allowed Milik to press both players simultaneously. Difficulty in building play from deep would become a recurring problem for Switzerland, particularly in the centre of the pitch.

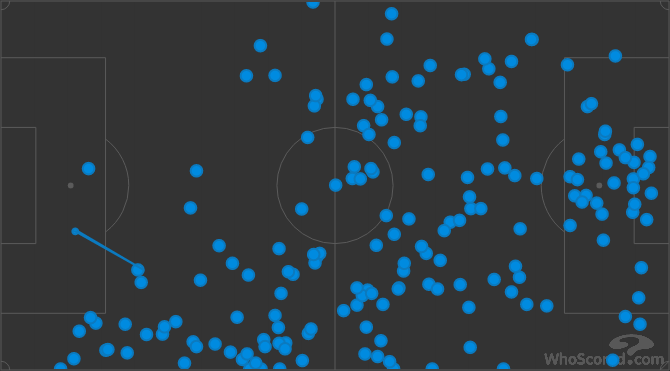

Granit Xhaka’s build-up performance is often representative of the team he plays for because of his consistent demand for the ball. In the opening stages of the game, he aimed to drop deep between the central defenders, with Behrami moving away from the ball. When this combination created little success, Xhaka adapted and instead dropped between the left-back and central defender. Whilst this still created a situational back three in the first line of build-up, Xhaka’s passing ability on the left created passing lanes that Djourou was not able to access.

This allowed a simple progression without any impressive Swiss structure, with Rodriguez able to isolate the opposition 1v1 in an individual duel. Xhaka would also occasionally be able to push play centrally with a diagonal pass into the halfspace, but poor structure and an outward-facing field of vision for the receiver made it difficult for play to progress. The most effective form of progression on the left for Switzerland came when Xhaka could pass directly to an inward-facing player on the touchline, with Rodriguez making an underlapping third-man run into the halfspace.

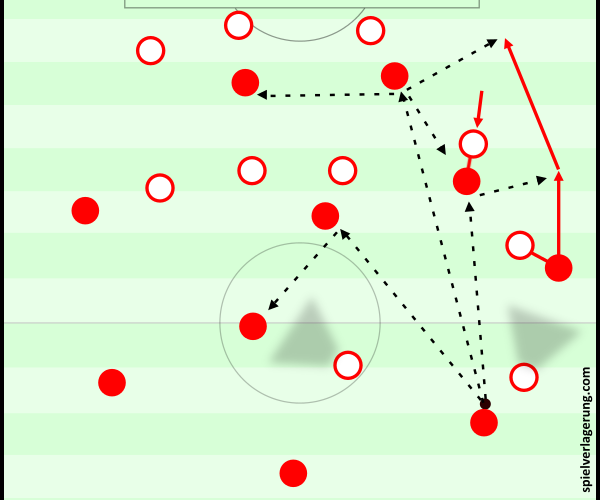

Eventually this focus on building play in wider areas played dividends, and Switzerland were able to create variable structures where the ball-player could utilise a number of different passing options. When Shaqiri drifted backwards from his advanced wing position to receive a vertical pass to feet, his defender often followed. Despite the proximity of the defender, this did not decrease Shaqiri’s availability for a pass, but it did create space behind them. This situation often occurred on the left also, but Lichtsteiner provided a more intelligent outlet for an immediate wall-pass than Rodriguez.

This successful structure was often a product of poor Polish defensive structure than intelligent Swiss build-up. It was the Polish plan for the ball-side forward to press the ball-player from the interior of the pitch and the other forward to drop deeper and man-orient to the Swiss central midfielder. As the game wore on this staggering was implemented less, with both forwards failing to contribute to the first phase of pressing. In the latter stages of the game, this negligence put the Polish midfield under considerable pressure.

The ever-weakening defensive structure also allowed Switzerland to push Xhaka into a more advanced central area, with Behrami instead dropping deeper.

Floating Swiss wingers

Both Swiss wingers were given license to drift away from their wing. At which point, the full-back on their side would push forward and attempt to occupy the opposition full-back directly. Instead of slightly indenting or drifting away, they utilised rigid movements to the alternate halfspace. Mehmedi and Shaqiri used this to overload one full-back and create combination play in wide areas.

It was rarely effective. Because Switzerland often had poor occupation of the far-side halfspace during their attacking organisation, the full-back on that side was disconnected from play and was not able to be reached with one pass. This allowed Poland to increase their compactness around the ball by shifting towards the previously overloaded zone.

Polish transitions

Much of the Polish threat came from quick transitions after a sustained period of defensive organisation. This was illustrated perfectly for the team’s goal, where the ball was in the hands of Fabianski only thirteen seconds before it found its way past Yann Sommer.

Grosicki got the assist for the goal, and was a recurring ingredient of Poland’s transitions throughout the game. During defensive organisation phases, he was situated in the halfspace rather than on the wing, increasing his transition availability when possession was eventually regained. If an opponent immediately engaged him in a 1v1 duel, he could utilise his outstanding agility and acceleration to glide past them from a standing start. If there was space on the left-side, he would move into it with the ball at speed. Often Lewandowski would drift wide to offer an immediate passing option, which allowed Grosicki to underlap him – generally leaving his direct opponent unable to keep pace with him.

If the transition began on the right of the pitch, Lewandowski would drop into midfield and demand the ball to feet. This reduced the speed of Poland’s attack, partly because it involved Lewandowski receiving the ball with his back to goal whilst teammates quickly progressed beyond him. Lewandowski also utilised similar movements in slower build-up play, with Grosicki moving forward into the vacated space. But this was similarly ineffective as Lewandowski was unable to receive the ball facing play, and often lost possession or killed the tempo whilst attempting to turn and evaluate potential passing options.

Extra time

An incredible bicycle kick in the 81st minute from Xherdan Shaqiri forced extra-time. The Swiss had already used all three of their subs by this time, and were therefore forced to play the added time with an overly attacking set of personnel. To the contrary, Poland had all three subs to utilise.

But neither of these factors seemed to create an open game, and the tempo slowed dramatically. Switzerland largely controlled possession, but when Poland did eventually regain the ball, poor central structures consistently forced them into wide areas. The far-side Polish winger and full-back seemed too tired to ball-orient, and hardly moved from the touchline. This disconnected them from play and made them unavailable for a pass. Poland were only able to progress play on the left, where Lewandowski continued to drift.

Conclusion

It’s said that penalties are a cruel way to complete a game, but Poland’s five kicks were all powerful strikes and expertly taken. In a fairly even game, one mistake from Xhaka seemed a fitting way to separate the teams. But if Poland are to continue their progression through the tournament, they will not be able to rely on poor opposition occupation of the centre of the pitch. Improved ball-oriented shifting, combined with their ruthless transition play, would make them a tough team to beat for any opposition.

Keine Kommentare vorhanden Alle anzeigen